Abstract

The results of this study show that c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation was associated with the enhancement of docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity by simvastatin in DU145 human prostate cancer cells. To better understand the basic molecular mechanisms, we investigated simvastatin-regulated targets during simvastatin-induced cell death in DU145 cells using two-dimensional (2D) proteomic analysis. Thus, vimentin, Ras-related protein Rab-1B (RAB1B), cytoplasmic hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase (cHMGCS), thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5 (TXNDC5), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K), N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1), and isopentenyl-diphosphate Delta-isomerase 1 (IDI1) protein spots were identified as simvastatin-regulated targets involved in DU145 cell death signaling pathways. Moreover, the JNK inhibitor SP600125 significantly inhibited the upregulation of NDRG1 and IDI protein levels by combination treatment of docetaxel and simvastatin. These results suggest that NDRG1 and IDI could at least play an important role in DU145 cell death signaling as simvastatin-regulated targets associated with JNK activation.

Keywords: Docetaxel, DU145 cell death, JNK, Proteomic analysis, Simvastatin-regulated targets

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer has become a major health issue in men due to relapse after androgen deprivation therapy, leading to incurable and highly aggressive castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) (1). Epidemiological studies have shown that high blood-cholesterol levels are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer, and can be reduced by cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins) (2). In addition to cholesterol reduction, statins, such as simvastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin, and atorvastatin, play an important role in the regulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, cell motility, invasion, and adhesion in various cancer cells (3, 4). Notably, it is known that castration-resistant progression in LNCap prostate cancer xenografts-bearing mice is delayed by oral administration of simvastatin (5), and the clinical use of statins after diagnosis decreases the risk of mortality in prostate cancer patients (6).

The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) belongs to the serine/threonine protein kinase family, and is activated through phosphorylation(s) by many stress stimuli, resulting in the phosphorylation of c-Jun transcription factor; this JNK activation signaling is markedly inhibited by the ATP-competitive inhibitor SP600125 (7). Previous studies have shown that JNK activation is involved in cell death signaling by simvastatin in rat C6 glioma cells (8), human leukemia cells (9), and breast cancer cells (10, 11). In addition, JNK activation is known to be associated with enhanced cytotoxicity by the combination of fluvastatin and sorafenib in melanoma cells (12), and the combined effect of statin and docetaxel has been studied in PC3 human CRPC cells (13, 14). However, the relevance of JNK activation signaling to statin-enhanced docetaxel-induced cell death has not yet been investigated. Since JNK activation signaling is related to statin-induced cell death in some cancer cell types (8–12), studies on a new JNK activation signaling network may contribute greatly to improving the chemotherapeutic effect of statins on various cancers, and remain to be investigated.

Simvastatin-regulated targets in the mitochondria fraction of rat adult brain tissue (15), acute phase of stroke in a rat embolic model (16), detergent-resistant membrane domains of rat embryonic neuronal cells (17), and mouse calvarial cells (18) and rat primary hepatocytes (19) using two-dimensional (2D) proteomic analysis after simvastatin treatment have already been known. However, simvastatin-regulated targets associated with JNK activation in DU145 human prostate cancer cell death signaling have not been reported. In this study, we investigated whether JNK activation is involved in the enhancement of docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity caused by simvastatin in DU145 cells, identified novel targets associated with simvastatin-induced morphological changes and cell death using 2D proteomic analysis, and examined whether the simvastatin-regulated targets are implicated in the JNK activation signaling during cytotoxicity by combination of docetaxel and simvastatin, through the effect of SP600125.

RESULTS

JNK activation signaling is associated with the enhancement of docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity caused by simvastatin in DU145 cells

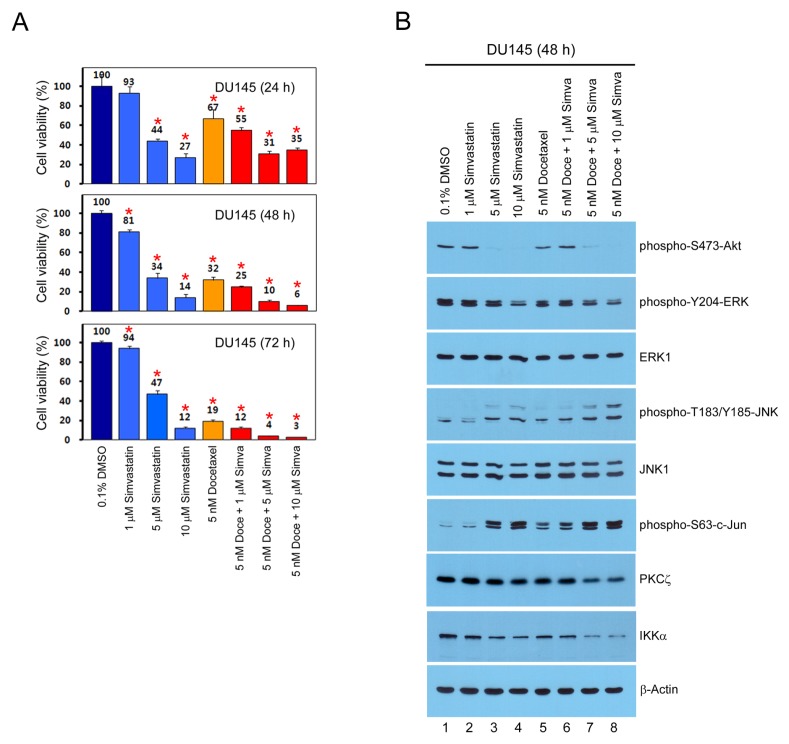

In this study, we used cell viability analysis to show that docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity was enhanced by simvastatin in a dose- (1, 5, and 10 μM) and time-dependent (24, 48, and 72 h) manner in DU145 human prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1A). To investigate whether JNK-dependent signaling is activated during cytotoxicity by combination treatment of docetaxel and simvastain, we performed Western blot analysis 48 h after drug treatment in DU145 cells. Fig. 1B shows that JNK phosphorylation was more upregulated by co-treatment of docetaxel and simvastatin compared to single treatment, leading to activation of the JNK downstream target c-Jun, whereas phosphorylation of Akt and ERK was downregulated. In addition, protein levels of protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ) and IκB kinase α (IKKα), which play an important role in nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation signaling pathways (20, 21), were more downregulated by the co-treatment of docetaxel and simvastatin, compared to single treatment (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that, as well as Akt, ERK, PKCζ, and IKKα inactivation signaling pathways, JNK activation signaling is significantly associated with the enhancement of docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity caused by simvastatin.

Fig. 1.

JNK activation signaling is associated with the enhancement of docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity caused by simvastatin in DU145 cells. (A) DU145 cells were split in a 24-well dish, and treated with 0.1% DMSO, 1–10 μM simvastatin (Simva), and 5 nM docetaxel (Doce) for 24–72 h. The cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay. Each bar represents the mean ± s.d. of three experiments, and the data significance was evaluated with Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05. (B) Total proteins (20–50 μg each) were analyzed by Western blot using the indicated antibodies.

Proteomic analysis of novel targets associated with simvastatin-induced morphological changes and cell death in DU145 cells

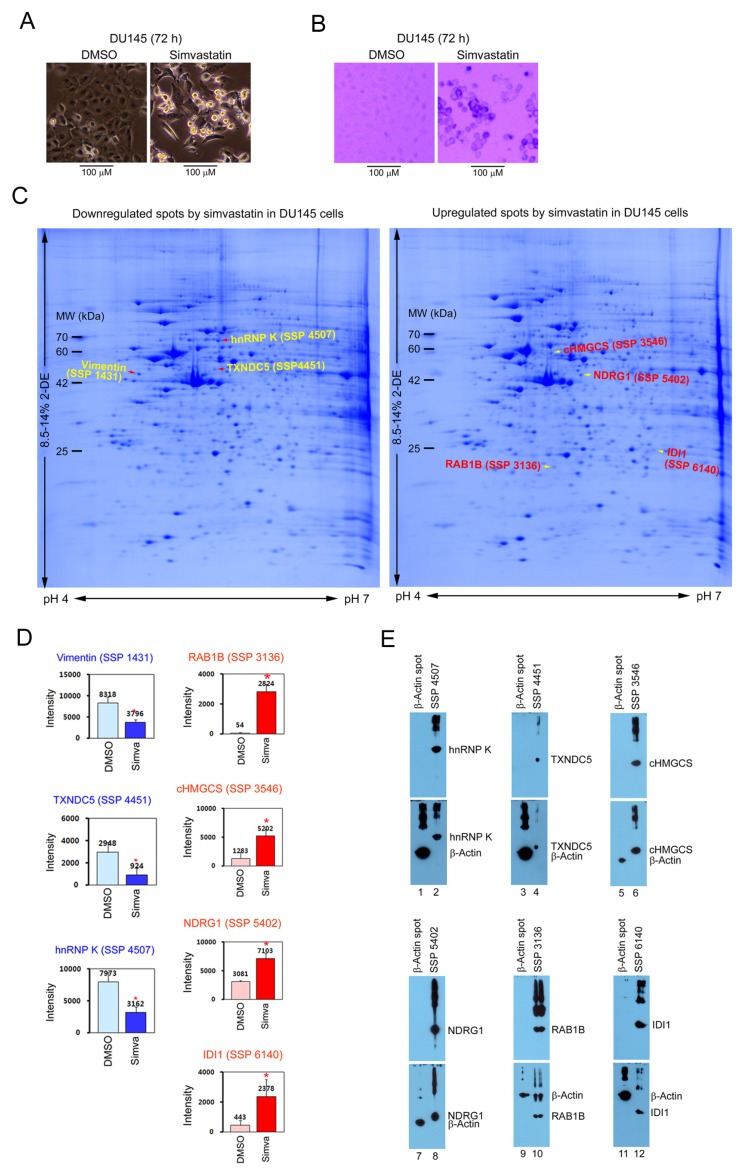

DU145 cell morphology was significantly altered by treatment with 10 μM simvastatin for 72 h: the attached cells had a modified cell body, and the floating cells were changed to a smaller round apoptotic phenotype, and were determined to be dead cells as a result of trypan blue staining (Fig. 2A and 2B). To identify novel targets associated with simvastatin-induced morphological changes and cell death, we performed 2D electrophoresis, CBB staining, and PDQuest image analysis 72 h after 10 μM simvastatin treatment in DU145 cells. Protein spots that were more than two-fold upregulated or downregulated by simvastatin were identified using matrix-associated laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) time of flight/time of flight (TOF/TOF) mass spectrometry, and Table 1 and Fig. 2C show the statistically significant results (P < 0.05). Fig. 2D shows the quantification results for 3 simvastatin-downregulated and 4 simvastatin-upregulated spots analyzed by PDQuest software with statistical significance (*P < 0.05). To confirm the identified results, each protein spot and a piece of β-actin spot as a negative control were picked from CBB-stained 2D gels, and were analyzed by Western blot. As expected, SSP 4507, 4451, 3546, 5402, 3136, and 6140 protein spots were confirmed as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K), thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5 (TXNDC5), cytoplasmic hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase (cHMGCS), N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1), Ras-related protein Rab-1B (RAB1B), and isopentenyl-diphosphate Delta-isomerase 1 (IDI1), respectively (Fig. 2E). Since vimentin (18) and NDRG1 (17) proteins are already known to be regulated by simvastatin, in this study we present five novel simvastat-inregulated targets, such as hnRNP K, TXNDC5, cHMGCS, RAB1B, and IDI1, suggesting a new role of the targets in the regulation of morphological changes and cell death caused by simvastatin.

Fig. 2.

Proteomic analysis of novel targets associated with simvastatin-induced morphological changes and cell death in DU145 cells. (A) The cell morphology was analyzed in a 6-well dish by phase-contrast light microscopy. (B) After trypan blue staining, dead cells were detected by bright-field phase-contrast light microscopy. (C) The 2D electrophoresis profile of simvastatinregulated protein spots. DU145 cells were cultured on a 15 cm dish with 0.1% DMSO (control) and 10 μM simvastatin for 72 h, and were analyzed by 2D electrophoresis and CBB staining. The 3 downregulated and 4 upregulated protein spots by simvastatin were identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometric analysis. Each protein spot is indicated by an arrow and SSP number on a representative 2D image. (D) Quantitative analysis of simvastatin-regulated protein spots. The relative intensities of the protein spots were determined using PDQuest software. Each bar represents the mean ± s.d. of four independent experiments, and the data significance was evaluated by Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05. (E) Verification of protein spots identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometric analysis. Each protein spot and a piece of β-actin spot were excised from CBB-stained 2D gels, and performed by 10% or 13.5% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were analyzed by Western blot using the indicated antibodies (upper panels). Without stripping, the membranes were reprobed by β-actin (lower panels).

Table 1.

Simvastatin-regulated protein spots in DU145 prostate cancer cells

| Spot number | Protein identification by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS | Tryptic fragment coverage/Matches | MASCOT probability score/Expect (p) | UniProtKB entry/Database | Theoretical Mr (Da)/pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1431 | Vimentin | 19%/10 fragment | 119/2.0e-007 | B0YJC4/NCBInr | 49680/5.19 |

| 3136 | Ras-related protein Rab-1B (RAB1B) | 17%/7 fragment | 99/2.1e-005 | Q9H0U4/NCBInr | 22328/5.55 |

| 3546 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic (cHMGCS) | 23%/11 fragment | 93/8.7e-005 | Q01581/NCBInr | 57828/5.22 |

| 4451 | Thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5 (TXNDC5) | 13%/11 fragment | 85/0.00055 | Q8NBS9/NCBInr | 48283/5.63 |

| 4507 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K) | 15%/10 fragment | 103/8.2e-006 | P61978/NCBInr | 51230/5.39 |

| 5402 | Protein NDRG1 (NDRG1 N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1) | 24%/13 fragment | 82/0.00098 | Q92597/NCBInr | 43264/5.49 |

| 6140 | Isopentenyl-diphosphate Delta-isomerase 1 (IDI1) | 34%/10 fragment | 128/2.6e-008 | Q13907/NCBInr | 26645/5.93 |

Effect of JNK inhibitor SP600125 on the simvastatin-regulated targets during cytotoxicity by combination of docetaxel and simvastatin

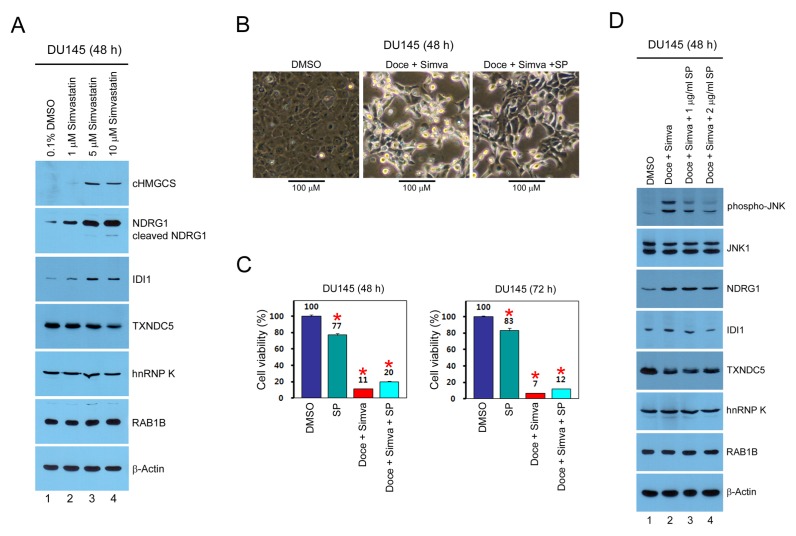

To prove the results of the 2D proteomic analysis, we used Western blot analysis to investigate how the identified targets are regulated by simvastatin in whole cell extract of DU145 cells. The results showed that cHMGCS, NDRG1, and IDI protein levels were dose-dependently increased by simvastatin treatment for 48 h, whereas TXNDC5 was downregulated by simvastatin, although the molecular weight of TXNDC5 (~70 kDa) was higher than that in Fig. 2C (~48 kDa), suggesting a massive posttranslational modification of TXNDC5 in normal proliferating DU145 cells (Fig. 3A). However for currently unknown reasons, no significant effect of simvastatin on the hnRNP K and RAB1B proteins was detected, suggesting an intracellular localization change of hnRNP K and RAB1B by simvastatin, followed by an alteration of solubility during 2D sample preparation (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effect of JNK inhibitor SP600125 on the simvastatin-regulated targets during cytotoxicity by combination of docetaxel and simvastatin. (A) Total proteins (30–50 μg each) were analyzed by Western blot using the indicated antibodies. (B) DU145 cells were split in a 10 cm dish, and treated with 0.3% DMSO, 5 nM docetaxel, 10 μM simvastatin, and 2 μg/ml SP600125 (SP) for 48 h. The cell morphology was analyzed by phase-contrast light microscopy. (C) DU145 cells were split in a 24-well dish, and treated with 0.2% DMSO, 2 μg/ml SP600125, 5 nM docetaxel, and 5 μM simvastatin for 48 and 72 h. The cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay. Each bar represents the mean ± s.d. of three experiments, and the data significance was evaluated by Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05. (D) DU145 cells were split in a 10 cm dish, and treated with 0.3% DMSO, 5 nM docetaxel, 10 μM simvastatin, and 1–2 μg/ml SP600125 for 48 h. Total proteins (25 μg each) were analyzed by Western blot using the indicated antibodies.

Next, we used phase-contrast light microscopy and cell viability analysis to investigate how morphological changes and cytotoxicity by combination of docetaxel and simvastatin are regulated by JNK inhibitor SP600125 in DU145 cells. As a result, morphological changes and cytotoxicity due to combination of docetaxel and simvastatin were somewhat significantly, but not largely, inhibited by JNK inhibitor SP600125, indicating that both JNK-dependent and -independent signaling pathways are implicated in cell death mechanisms by docetaxel and simvastatin (Fig. 3B and 3C). Finally, we performed Western blot analysis in whole cell extract of DU145 cells to determine whether the identified targets are associated with JNK activation signaling by combination of docetaxel and simvastatin. Notably, upregulation of NDRG1 and IDI protein levels by co-treatment of docetaxel and simvastatin for 48 h was dose-dependently inhibited by SP600125, whereas down-regulation of TXNDC5 had no significant effect on SP600125 (Fig. 3D). The hnRNP K and RAB1B protein levels were not altered by combination of docetaxel and simivastatin, and had no significant effect by SP600125 (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the identified simvastatin-regulated targets may play an important role in the regulation of morphological changes and cell death by combination of docetaxel and simvastatin via JNK-dependent and -independent signal transduction pathways in various cancer cells.

DISCUSSION

Statins inhibit the mevalonate pathway, which is essential for the synthesis of various compounds, including cholesterol, through the suppression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase (HMGCR) (3). Simvastatin is one of the most commonly used statins, and is known to induce apoptosis in glioma (8), leukemia (9), and breast cancer cells (10, 11) through JNK activation signaling. Docetaxel is the most commonly prescribed anti-cancer agent in the standard first-line chemotherapy for metastatic CRPC (22). In this study, we demonstrated that JNK activation signaling was associated with the enhancement of docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity by simvastatin in DU145 human prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1).

It is known that downregulation of vimentin is associated with the inhibition of TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by simvastatin in DU145 prostate cancer cells (23); downregulation of RAB1B promotes the proliferation and migration of triple-negative breast cancer cells by activating TGF-β1/SMAD signaling (24); TXNDC5 overexpression is associated with non-small cell lung carcinoma (25) and CRPC tumor (26); NDRG1 mediates tumor-suppressive effects of the iron chelator Dp44mT in prostate cancer cells through the PI3K/Akt, TGF-β and ERK pathways (27); and the intracellular localization and phosphorylation status of hnRNP K are implicated in the mechanisms that regulate androgen receptor expression and activity (28, 29). In addition, it is known that high mRNA levels of HMGCR and HMGCS1 are correlated with poor prognosis of primary breast cancer (30); IDI1 functions in the terpenomic diversity by catalyzing the conversion of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) into dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) in the mevalonate-isoprenoid biosynthesis (MIB) pathway (31); and downregulation of the MIB pathway is associated with the attenuation of colorectal cancer stem cell growth through the inhibition of insulin-like growth factor receptor/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling (32).

In this study, we used 2D proteomic analysis to identify five novel simvastatin-regulated targets (hnRNP K, TXNDC5, cHMGCS, RAB1B, and IDI1), and two previously known simvastatin-regulated targets (vimentin and NDRG1) (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Moreover, our results have shown that NDRG1 and IDI1 proteins are at least involved in JNK activation signaling during cytotoxicity by the combination of docetaxel and simvastatin (Fig. 3D). Taken together, we propose seven simvastatin-regulated targets that could play a crucial role in the regulation of cell morphology, death, and lipid metabolism through JNK-dependent and -independent signal transduction pathways. Future molecular and cellular studies of these simvastatin-regulated targets are expected to provide a new chemotherapeutic mechanism in various cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2013R1A1A 2058019, NRF-2015R1D1A1A01060190, and NRF-2016R1D 1A1B03936127).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katsogiannou M, Ziouziou H, Karaki S, Andrieu C, Henry de Villeneuve M, Rocchi P. The hallmarks of castration-resistant prostate cancers. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:588–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krycer JR, Brown AJ. Cholesterol accumulation in prostate cancer: A classic observation from a modern perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 20131835:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osmak M. Statins and cancer: Current and future prospects. Cancer Lett. 2012;324:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altwairgi AK. Statins are potential anticancerous agents (Review) Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1019–1039. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon JA, Midha A, Szeitz A, et al. Oral simvastatin administration delays castration-resistant progression and reduces intratumoral steroidogenesis of LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:21–27. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2015.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu OEberg M, Benayoun S, et al. Use of statins and the risk of death in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:5–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogoyevitch MA, Arthur PG. Inhibitors of c-Jun N-terminal kinases: JuNK no more? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koyuturk M, Ersoz M, Altiok N. Simvastatin induces proliferation inhibition and apoptosis in C6 glioma cells via c-jun N-terminal kinase. Neurosci Lett. 2004;370:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YJ, Chang LS. Simvastatin induces NFκB/p65 down-regulation and JNK1/c-Jun/ATF-2 activation, leading to matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) but not MMP-2 down-regulation in human leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;92:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koyuturk M, Ersoz M, Altiok N. Simvastatin induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells: p53 and estrogen receptor independent pathway requiring signalling through JNK. Cancer Lett. 2007;250:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopalan A, Yu W, Sanders BG, Kline K. Simvastatin inhibition of mevalonate pathway induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells via activation of JNK/CHOP/DR5 signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2013;329:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Doudican NA, Quay E, Orlow SJ. Fluvastatin enhances sorafenib cytotoxicity in melanoma cells via modulation of AKT and JNK signaling pathways. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3259–3265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goc A, Kochuparambil ST, Al-Husein B, Al-Azayzih A, Mohammad S, Somanath PR. Simultaneous modulation of the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways by simvastatin in mediating prostate cancer cell apoptosis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:e409. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Liu Y, Wu J, et al. Mechanistic study of inhibitory effects of atorvastatin and docetaxel in combination on prostate cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2016;13:151–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pienaar IS, Schallert T, Hattingh S, Daniels WM. Behavioral and quantitative mitochondrial proteome analyses of the effects of simvastatin: implications for models of neural degeneration. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:791–806. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campos-Martorell M, Salvador N, Monge M, et al. Brain proteomics identifies potential simvastatin targets in acute phase of stroke in a rat embolic model. J Neurochem. 2014;130:301–312. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponce J, Brea D, Carrascal M, et al. The effect of simvastatin on the proteome of detergent-resistant membrane domains: Decreases of specific proteins previously related to cytoskeleton regulation, calcium homeostasis and cell fate. Proteomics. 2010;10:1954–1965. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang R, Lee EJ, Kim MH, et al. Calcyclin, a Ca2+ ion-binding protein, contributes to the anabolic effects of simvastatin on bone. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21239–21247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho YE, Moon PG, Lee JE, et al. Integrative analysis of proteomic and transcriptomic data for identification of pathways related to simvastatin-induced hepatotoxicity. Proteomics. 2013;13:1257–1275. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirai T, Chida K. Protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ): activation mechanisms and cellular functions. J Biochem. 2003;133:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang WC, Hung MC. Beyond NF-κB activation: nuclear functions of IκB kinase α. J Biomed Sci. 2013;20:e3. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-20-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JJ, Zhang J. Sequencing systemic therapies in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Control. 2013;20:181–187. doi: 10.1177/107327481302000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie F, Liu J, Li C, Zhao Y. Simvastatin blocks TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human prostate cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3377–3383. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang HL, Sun HF, Gao SP, et al. Loss of RAB1B promotes triple-negative breast cancer metastasis by activating TGF-β/SMAD signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:16352–16365. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent EE, Elder DJ, Phillips L, et al. Overexpression of the TXNDC5 protein in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:1577–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Song G, Chang X, et al. The role of TXNDC5 in castration-resistant prostate cancer-involvement of androgen receptor signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2015;34:4735–4745. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon KM, Lui GY, Kovacevic Z, et al. Dp44mT targets the AKT, TGF-β and ERK pathways via the metastasis suppressor NDRG1 in normal prostate epithelial cells and prostate cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:409–419. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barboro P, Salvi S, Rubagotti A, et al. Prostate cancer: Prognostic significance of the association of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K and androgen receptor expression. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:1589–1598. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barboro P, Borzì L, Repaci E, Ferrari N, Balbi C. Androgen receptor activity is affected by both nuclear matrix localization and the phosphorylation status of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K in anti-androgen-treated LNCaP cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clendening JW, Pandyra A, Boutros PC, et al. Dysregulation of the mevalonate pathway promotes transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15051–15056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910258107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthelot K, Estevez Y, Deffieux A, Peruch F. Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase: A checkpoint to isoprenoid biosynthesis. Biochimie. 2012;94:1621–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharon C, Baranwal S, Patel NJ, et al. Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor receptor/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin axis targets colorectal cancer stem cells by attenuating mevalonate-isoprenoid pathway in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2015;6:15332–15347. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.