Summary

Tuft cells (TCs) are minor components of gastrointestinal epithelia, characterized by apical tufts and spool-shaped somas. The lack of reliable TC-markers has hindered the elucidation of its role. We developed site-specific and phosphorylation-status–specific antibodies against Girdin at tyrosine-1798 (pY1798) and found pY1798 immunostaining of mouse jejunum clearly depicted epithelial cells closely resembling TCs. This study aimed to validate pY1798 as a TC-marker. Double-fluorescence staining of intestines was performed with pY1798 and known TC-markers, for example, hematopoietic-prostaglandin-D-synthase (HPGDS), or doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated from cell counts to determine whether two markers were attracting (OR<1) or repelling (OR>1). In consequence, pY1798 signals strongly attracted those of known TC-markers. ORs for HPGDS in mouse stomach, small intestine, and colon were 0 for all, and 0.08 for DCLK1 in human small intestine. pY1798-positive cells in jejunum were distinct from other minor epithelial cells, including goblet, Paneth, and neuroendocrine cells. Thus, pY1798 was validated as a TC-marker. Interestingly, apoptosis inducers significantly increased relative TC frequencies despite the absence of proliferation at baseline. In conclusion, pY1798 is a novel TC-marker. Selective tyrosine phosphorylation and possible resistance to apoptosis inducers implied the activation of certain kinase(s) in TCs, which may become a clue to elucidate the enigmatic roles of TCs.

Keywords: brush cell, Girdin, tuft cell marker, tyrosine phosphorylation

Introduction

Tuft cells (TCs) are minor scattered components in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract, originally described in 19561 as spool-shaped epithelial cells with “tuft”-like bristles. The definition of TCs (or brush cells) is largely dependent on their morphology.2 Regardless of their resident organ (digestive tract or respiratory tract),1,3,4 TCs share common characteristics, including (1) sporadic distribution, (2) spool-shaped somas,5 and (3) long and thick microvilli extending to the supra-nuclear region to form rootlets without forming a terminal web at the lumenal surface, unlike enterocytes in the small intestine. Little is currently known, however, about the primary causes of such morphological characteristics.

Several molecular markers of TCs are also known, for example, villin, F-actin–reactive phalloidin, glycocalyx-reactive lectins, cyclooxygenase-1/2 (Cox1/2), doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1), and hematopoietic-prostaglandin-D-synthase (HPGDS).6,7 However, these known TC-markers are less than optimal. For example, some TC-markers (e.g., villin, phalloidin) only stain limited subcellular regions of TCs, whereas other markers (e.g., lectin Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1 [UEA-1]) also show reactivity in epithelial cells other than TCs, such as neuroendocrine cells, goblet cells, and Paneth cells.7 To the best of our knowledge, there is no TC-marker, which can universally mark TCs in multiple organs of multiple species with high contrast. Given this limitation, it has been difficult to elucidate the enigmatic role of TCs in multiple tissues. Even though TCs account for a considerable proportion of epithelial cells in certain organs (7% of rat salivary glands2 and 30% of rat common bile duct8), until recently there have been very few functional studies on TCs.6 A series of reports has recently identified a possible role for TCs in protection against parasitic infection in the gut.9,10 However, these reports did not identify a broader role for TCs within organs other than the small intestine.

In 2005, our group identified the Girdin/CCDC88A gene product as an F-actin–binding protein containing a coiled-coil domain, which has putative roles in cell migration via the modulation of the actin cytoskeleton.11 Other groups also identified that Girdin interacts with several key cellular elements and proteins, including microtubules, heterotrimeric G proteins, and early endosomes.12,13 Global Girdin knockout mice exhibited complete preweaning lethality due to malnutrition, as well as the developmental abnormalities in brain.14–17 Lin et al.18 discovered that on ligand stimulation of various receptors, Girdin is phosphorylated at tyrosine-1798 of Girdin (Y1798), eventually triggering cell migration. As the amino-acid sequence of human Girdin around Y1798 (KDSNPYATLPRAS) is highly conserved among mammalian species, we generated site-specific and phosphorylation-status–specific antibodies against phosphorylated tyrosine-1798 (pY1798) in human Girdin.19 We applied this antibody for immunohistochemical analysis of mammalian gut, and observed specific staining of epithelial cells closely resembling TCs. The aims of this study were to validate pY1798 as an authentic TC-marker, and to open up a new field in TC research using pY1798 antibodies as a novel tool.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (26323) and by the Recombinant DNA Safety Committee (09-73) of the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine. Paraffin blocks of human tissues were obtained under the approval of ethical committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine. This article does not contain any individual person’s data.

Mouse Strains

All mice were housed in cages with woodchip-bedding at 23C on a 12-hr light/dark cycle. For apoptosis induction tests and age-dependent expression analysis, DDY mice were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). The construction of the gene-targeting vector for global Girdin knockout mice has been previously described.14 The following PCR primers were used: 5′-GCCGGAATGAACTTTCATTGATTCCGTC-3′ and 5′-CAGCCAGAGGTCCAAACGTTTTAACC-3′ to detectwild-type alleles (amplicon 293-bp) and 5′-CGCGGATTGGCCTGAACTGC-3′ and 5′-CCAGGAGTCGTCGCCACCAA-3′ to detect LacZ alleles (352-bp).

Human Tissues

Normal regions of surgically resected or endoscopically obtained tissues were collected in Nagoya University Hospital.

Paraffin Sections and Free-Floating Cryosections

Anesthetized mice were perfused with a 10% buffered neutral formalin solution. Collected tissues were immersed in ethanol, xylene, and molten paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4 µm, and were mounted on MAS-coated glass slides (S9441; Matsunami, Osaka, Japan). For free-floating sections, tissues were cryoprotected with 15% sucrose in formalin solution overnight, and were snap-frozen in liquid isopentane cooled with liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were sectioned at 30 µm at −20C using a cryostat (CM3050S; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Antibodies

The sources of antibodies and staining reagents are listed in Supplemental Fig. 6. Site-specific and phosphorylation-status–specific anti-Girdin rabbit polyclonal antibodies were collectively developed with IBL, Co., Ltd. (Gunma, Japan).20

Immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinized sections were boiled for target retrieval at each optimal pH (6, 7, or 9) at 98C for 30 min. Sections were serially treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol, protein block serum-free (X0909; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), and primary antibodies at 4C overnight. After washing in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), sections were incubated with secondary antibodies. When the host species of primary antibodies were rabbit or mouse, EnVision System HRP-labeled polymer (rabbit, K4003, or mouse, K4001; Dako) was used. For primary antibodies from goat, donkey polyclonal anti-MTR antibody (705-065-147; Jackson-Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) and streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (426062; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) were utilized. After color reaction with diaminobenzidine (liquid DAB substrate, K3468; Dako), slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, hematoxylin–eosin, or alcian blue (8GX, 010-08921; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan)/nuclear fast red (H-3403; Vector-Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Brains from wild-type mice or Girdin knockout mice were used for positive or negative controls of Girdin pY1798 immunohistochemistry (IHC), respectively. For IHC using commercially available antibodies, validations of the staining results were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fluorescence Staining

All fluorescence staining using phalloidin or UEA-I was performed on free-floating cryosections. Other fluorescence staining was done using paraffin sections. After primary-antibody–bound sections were washed with PBS, fluorescent-secondary antibodies were applied. For double-fluorescence staining using two rabbit polyclonal antibodies, individual antibodies were separately labeled using the Zenon Alexa Fluor 488 (or 594) rabbit IgG labeling kit (Z25302 or Z25307; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were counterstained with 1:1000–diluted 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; D1306; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Coverslips were mounted with crystal/mount (Biomeda, Foster City, CA). TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was performed using the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL System (G3250; Promega, Fitchburg, WI). Fluorescence images were acquired with excitation wavelengths of 405, 488, and 555 nm using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM700; Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Apoptosis Induction Test by Cisplatin

Cisplatin [cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (CDDP), Briplatin, 10 mg/20 mL] was purchased from Bristol Myers Squibb (New York, NY). Seven-week-old male DDY mice (n=32) were divided into four groups: (1) control (n=8), (2) low-dose (CDDP 0.2 mg/body, n=8), (3) middle-dose (0.4 mg/body, n=8), and (4) high-dose (0.8 mg/body, n=8). The indicated dose of cisplatin was administered in a single intraperitoneal injection. Mice were euthanized for tissue collection 24 or 48 hr after administration.

Apoptosis Induction Test by X-Ray

Seven-week-old male DDY mice (n=16) were divided into four groups: (1) control (0 Gy, n=4), (2) low-dose (0.5 Gy, n=4), (3) middle-dose (5 Gy, n=4), and (4) high-dose (15 Gy, n=4). Four awake mice from each group in a divided cage were placed in an X-ray irradiation device (MBR-1520R-3; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), and were subjected to the indicated dose of total-body irradiation. Metallic filters of 0.5-mm aluminum and 0.3-mm copper were attached to minimize low-energy X-rays. Mice were euthanized for tissue collection 24 hr after irradiation.

Transmission Electron Microscopy With Pre-Embedding Immunostaining

Paraffin sections (10 µm thick) of mouse small intestine were deparaffinized, and were immunostained with pY1798 anti-Girdin antibodies as per the stated procedure up to DAB color reaction. Sections were post-fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (073-00536; Wako Pure Chemical) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 hr at 4C, and with 2% osmium tetroxide (TAAB; Berks, UK) for 2 hr at 4C. Sections were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and 100% propylene oxide (165-05026; Wako Pure Chemical). Liquid epoxy was prepared by mixing 12.65 mL of epon 812 resin (T023), 5.575 mL of dodecenylsuccinic anhydride (D026), 6.8 mL of methyl nadic anhydride (M012), and 0.375 mL of 2,4,6-tris(dimethylaminomethyl)phenol (D035), all from TAAB. Inverted embedding capsules (C063/J; TAAB) filled with liquid epoxy were set on stained sections on MAS-coated glass slides (Matsunami), solidified at 60C for 48 hr, and were cooled at room temperature. Solidified epoxy and underlying tissues together with embedding capsules were popped off the glass slide. Tissue on the surface of the epoxy was trimmed and was submitted to ultrathin sections at 60 nm using an ultramicrotome (UC7; Leica Microsystems). Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate (73943; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min and lead citrate (L018; TAAB) for 3 min, and were observed under a transmission electron microscope (JEM1400; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, t-test, and one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni’s post hoc test were performed mainly using SPSS Statistics, Version 22 (IBM; Armonk, New York). Bar graphs of averaged values are shown as means ± standard errors. p values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

pY1798 Revealed Epithelial Cells Closely Resembling TCs in the Mammalian Gut

We first attempted IHC of mouse jejunum using newly developed site-specific and phosphorylation-status–specific antibodies against human Girdin tyrosine-1798 (pY1798 antibodies).20 We previously verified the specificity of the pY1798 antibodies using (1) dot-blot assay with phospho/unphosphorylated peptides, (2) western blot of HEK293FT cells transfected with a Girdin expression vector with/without the tyrosine-phenylalanine substitution at 1798 (Y1798F), (3) immunofluorescence of kinase-stimulated cell-lines, and (4) IHC of Girdin wild-type/knockout mouse brains.20 These pY1798 antibodies identified sporadic strongly stained epithelial cells with unusual morphological characteristics, including spool-shaped somas with a single mass of signal condensation at each lumenal tip (Fig. 1A, upper). pY1798-positive epithelial cells were (1) found throughout the entire small intestine, (2) widely scattered from crypt to villus tip, and (3) never adjacent to each other. pY1798-positive cells accounted for about 1% of the entire epithelium in the mouse jejunum, in which the percentage showed regional variation as well as individual animal variability. Regarding the subcellular localization, the pY1798 staining was not restricted to the apical microvilli, but was also present in all over the cytoplasm, including the apical cytoplasm (above and around the nucleus) and the sub-membranous area. pY1798 staining was barely seen within the nuclei. Besides the epithelium, pY1798-positive cells were sporadically observed in the lamina propria. The appearance of pY1798-positive epithelial cells in the mouse jejunum was indistinguishable from previously reported TCs labeled with Cox2 (Fig. 1A, lower). In contrast to the clear staining obtained with pY1798 (post-absorbed with unphosphorylated Y1798 peptide), pre-absorbed pY1798 antibodies did not specify TC-like epithelial cells, and instead labeled a broad spectrum of cells, indicating the widespread presence of unphosphorylated Girdin at Y1798 in enterocytes of the mouse jejunum (Fig. 1B).

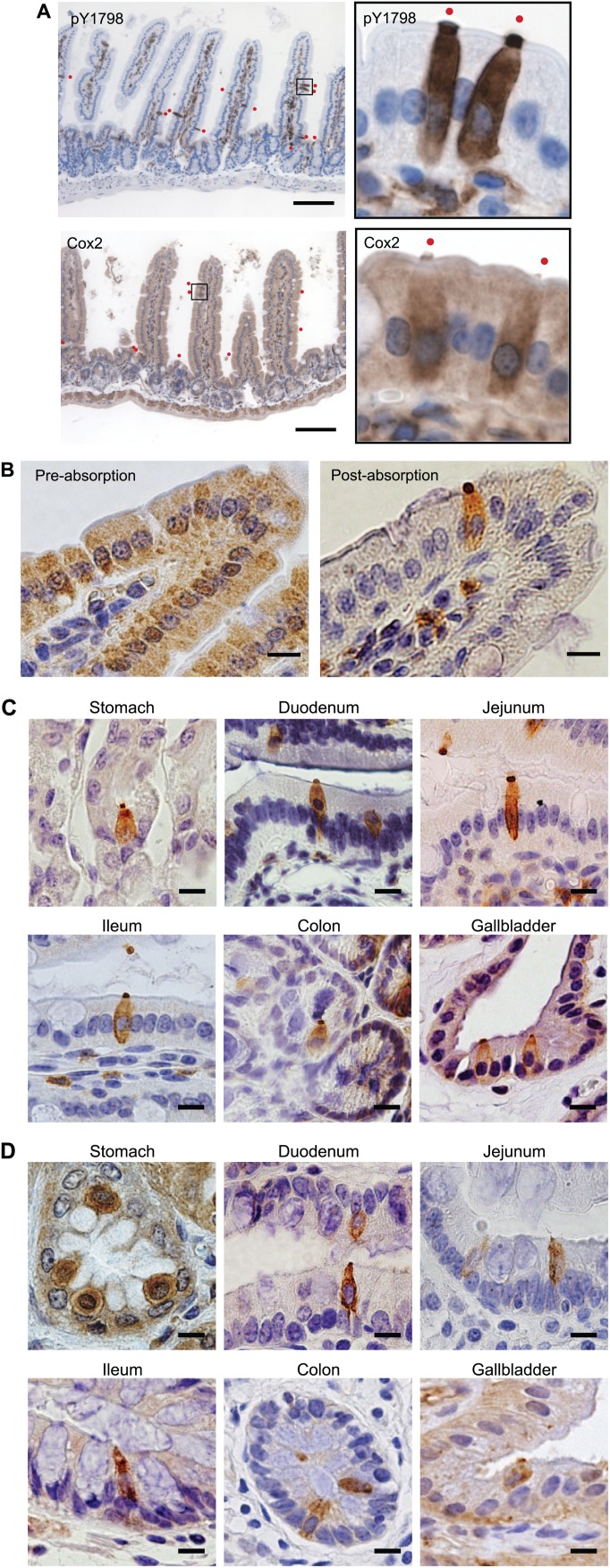

Figure 1.

pY1798 reveals epithelial cells closely resembling tuft cells (TCs) in the mammalian gut. (A) Immunohistochemistry of mouse jejunum with anti-Girdin phospho-Y1798 (pY1798) antibodies or with cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox2) antibodies. The boxed areas in the low-magnification images (scale bar, 100 µm) were magnified, rotated, and shown on each right side. Red dots represent positive epithelial cells. Immunohistochemistry of mouse jejunum with pY1798 antibodies pre-absorption (B, upper), or post-absorption (B, lower) using unphosphorylated Y1798 peptides (scale bars, 10 µm). Immunohistochemistry of mouse (C) and human (D) gastrointestinal tracts with pY1798 antibodies (scale bars, 10 µm).

IHC of multiple organs (stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, and gallbladder) from mouse and human for pY1798 also revealed sporadic epithelial cells with similar morphological characteristics of TCs (Fig. 1C and D). pY1798 signals were not observed in the esophagus, suggesting the specific distribution of pY1798-positive epithelial cells within columnar epithelia.

In previous publications, intestinal TCs were often drawn in illustrations as epithelial cells with somas slightly deviated toward the lumen.5 TCs double-positive for pY1798 and villin had a similar deviation tendency in all tested tissues in human and mouse to a varying degree (Fig. 1C and D, Supplemental Fig. 3).

Even in the small intestine of global Girdin knockout mice, TCs were labeled with known TC-markers (lectin UEA-I, or Cox2; Supplemental Fig. 1A). In contrast, pY1798-positive epithelial cells were completely invisible in knockout mouse organs (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and gallbladder; Supplemental Fig. 1B), clearly indicating that the pY1798 antibody specifically recognizes mouse Girdin gene products.

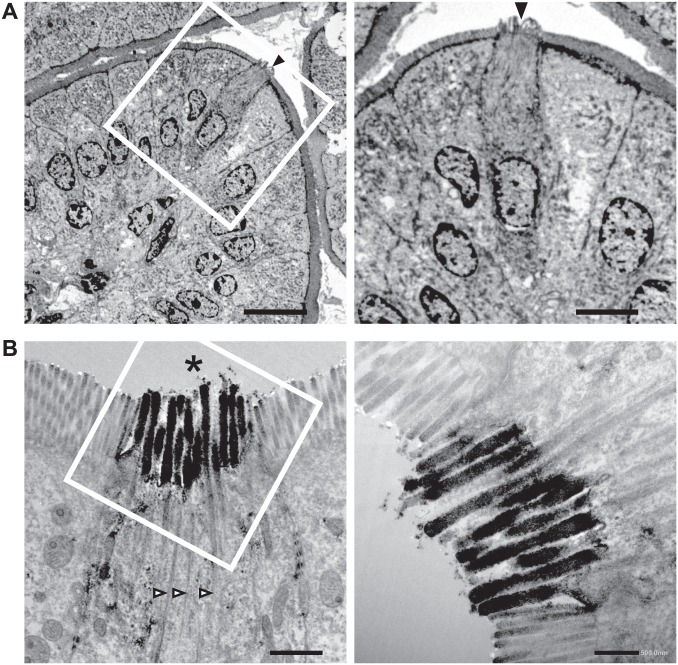

Validation of pY1798 as a TC-Marker by Transmission Electron Microscopy

Despite the lack of consensus molecular markers to define TCs, the earliest TC researchers described the morphological characteristics of TCs using transmission electron microscopy (TEM).4 The most characteristic morphological features of TCs include spool-shaped somas, long and blunt microvilli with prominent rootlets, and a well-developed tubulovesicular system in the supra-nuclear cytoplasm.2 To validate pY1798 as a novel TC-marker, we performed TEM of mouse jejunum sections, which underwent pre-embedding immunostaining for pY1798. TEM results showed that all pY1798-positive epithelial cells had spool-shaped somas with thick microvilli that no longer formed a terminal web at the basal portion of the microvilli; instead, they formed rootlets that extended deep into the cytoplasm of the supra-nuclear region of pY1798-positive cells (Fig. 2A and B). The TEM images of pY1798-positive epithelial cells were very similar to previously reported TC images.21 All pY1798-positive epithelial cells possessed the characteristic morphology of TCs, and all cells with TC morphology were pY1798 positive, indicating that the pY1798 antibody efficiently labeled all TCs. TC microvilli were more “blunt” than those of surrounding enterocytes, as previously described.21 These findings confirmed that the signal condensation at the lumenal tips of pY1798 epithelial cells is a collective entity consisting of TC microvilli, which are thicker than those in normal enterocytes, which form the brush border of the small intestine. Thus, pY1798 was validated as a novel TC-marker based on ultrastructure.

Figure 2.

Validation of pY1798 as a tuft cell (TC)-marker by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM of pY1798-immunostained jejunum (A and B). Boxed regions are shown magnified in the right panels. (A) A positive epithelial cell (arrowhead) protrudes beyond the brush border. (B) The signal condensation at the lumenal tip (asterisk) of a pY1798-positive epithelial cell comprises thick microvilli accompanied by rootlets (open arrowheads; scale bars in A, left, 10 µm; A, right, 5 µm; B, left, 1 µm; and B, right, 0.5 µm).

Validation of pY1798 as a TC-Marker by Double-Staining

We further continued the validation of pY1798 as a TC-marker by double-fluorescence staining using pY1798 and known TC-markers. For objective interpretation of the staining results, cell counts from double-fluorescence staining were arranged in 2 × 2 contingency tables, and odds ratios (ORs; bc/ad) were calculated to determine if pY1798 positivity (reference) and known TC-marker positivity (target) were attracting (OR<1) or repelling (OR>1). Simultaneously, the p values for two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests were calculated to determine if the odds of a target marker’s positivity were significantly different between the pY1798-positive and pY1798-negative groups (Fig. 3A).

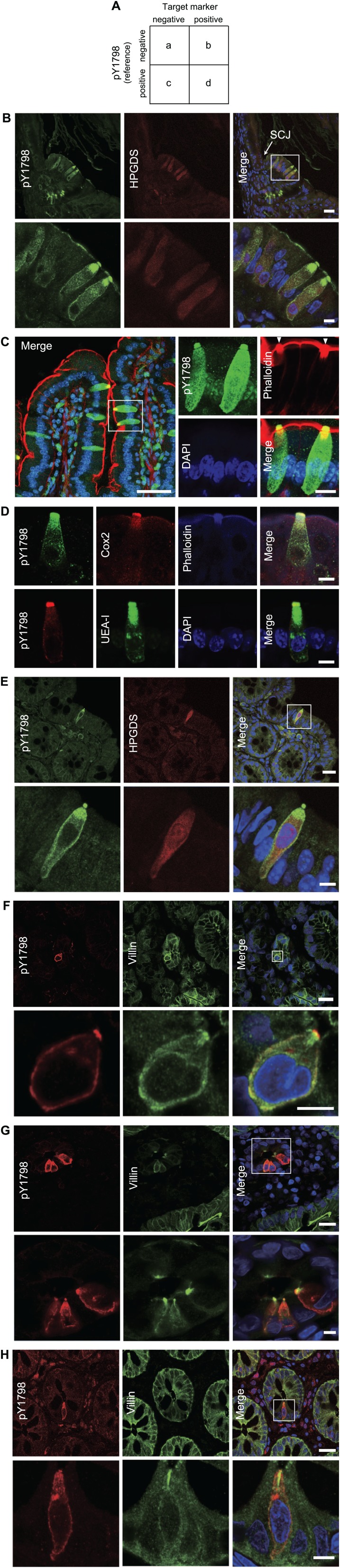

Figure 3.

Validation of pY1798 by co-staining with known tuft cells (TC)–markers. (A) The resultant counts of immunofluorescent cells were arranged in a 2 × 2 contingency table. Odds ratios (ORs; bc/ad) were calculated from these cell counts. Representative results of immunofluorescence using a reference marker (pY1798) and one or two target markers including hematopoietic-prostaglandin-D-synthase (HPGDS; B and E), phalloidin (C and D), cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox2; D), lectin UEA-I (D), and villin (F–H), in tissue sections from multiple organs, including stomach (B and F), small intestine (C, D, and G), and colon (E and H) from mouse (B–E) and human (F–H). The columnar side of the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) of mouse stomach frequently contained pY1798–HPGDS double-positive TCs (B). Focal thickenings of the brush border (white arrowheads) consistently colocalized with pY1798 (C; scale bars, upper panels, 20 µm; lower panels, 5 µm in B and E–H). In Panel C, the boxed region in the left panel (scale bar, 20 µm) is shown magnified and rotated in the four panels at right (scale bar, 10 µm; Panel D, 10 µm). Abbreviation: DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Actual fluorescence staining showed that pY1798-positive epithelial cells and known TC-marker–positive epithelial cells (labeled with HPGDS, phalloidin, Cox1/2, lectin UEA-I, villin, DCLK1, SH2-containing inositol phosphatase, growth factor independent 1B transcriptional repressor, and POU domain class 2 transcription factor 3) highly overlapped in multiple organs from both mouse (Fig. 3B–E, Supplemental Fig. 2A and B) and human (Fig. 3F–H, Supplemental Fig. 3). The possibility of autofluorescence detection in double-fluorescence staining was rigorously excluded by confirming the presence of distinct subcellular distributions of signals for pY1798 and known TC-markers. The columnar side of the squamocolumnar junction of mouse stomach frequently contained TCs (Fig. 3B). Phalloidin–pY1798 double-fluorescence staining exhibited perfect association between epithelial cells with a thickened brush border (a signature of TCs) and pY1798-positive cells (Fig. 3C). The thickness of the brush border in pY1798-positive epithelial cells was typically 3-fold that of the brush border in pY1798-negative cells.

Calculated ORs, p values, and total counts (=a+b+c+d) for HPGDS versus pY1798 in mouse stomach, small intestine, and colon were 0, <0.0001, 84; 0, <0.0001, and 548, and 0, <0.0001, and 277, respectively, and for DCLK1 versus pY1798 in human small intestine were 0.08, <0.0001, and 353, respectively (Fig. 3B and E). The odds of each known marker were significantly different depending on pY1798 positivity (p<0.05), due to the strong attracting tendency of the two markers (OR<1). Further comparison between pY1798 and villin, another known TC-marker, was conducted using double-fluorescence staining of human biopsy sections followed by hematoxylin–eosin staining (post-immunofluorescence hematoxylin–eosin staining [post-IF-HE]) to clearly visualize the structures surrounding TCs. In the human stomach, some TCs were present in fundic epithelia, whereas some were in foveolar epithelia (Supplemental Fig. 3). Although background villin staining was broadly observed on the lumenal surface of tested tissues, condensed villin signals were found in a strict association with the supra-nuclear regions of pY1798-positive epithelial cells.

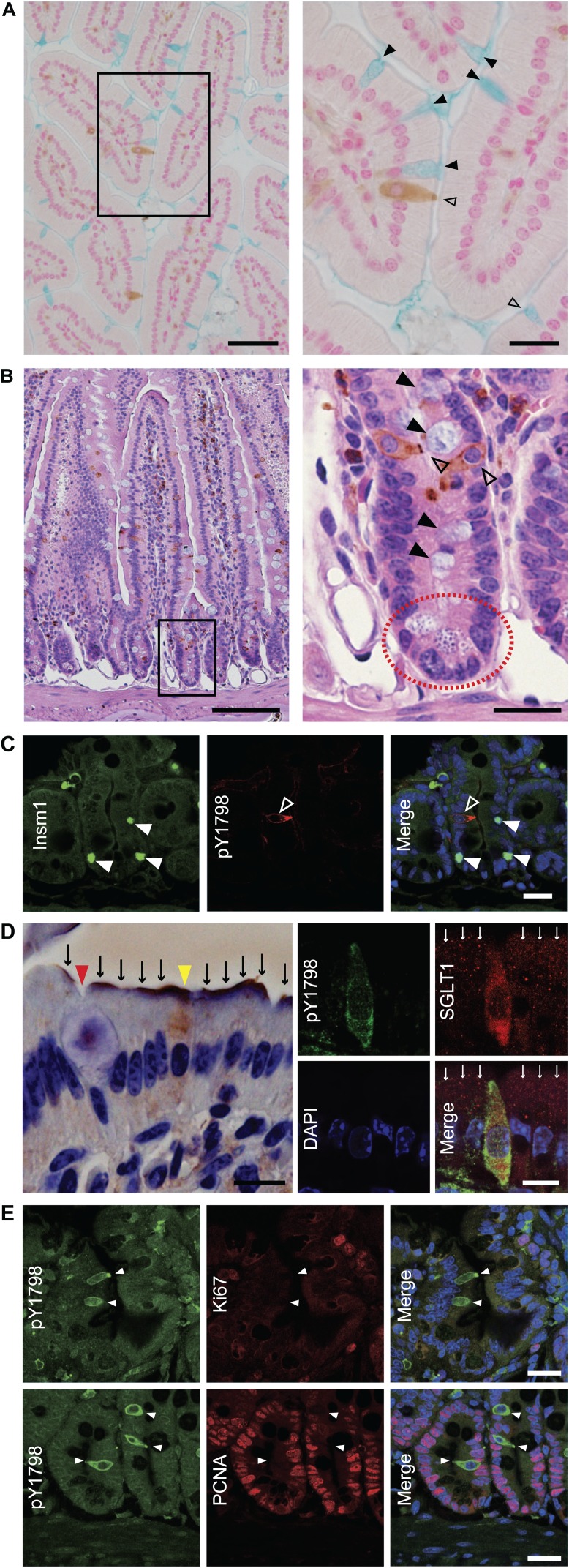

We then tried to confirm the absence of an overlap between TCs and other epithelial populations (goblet cells, Paneth cells, neuroendocrine cells, or enterocytes). IHC of mouse small intestine for pY1798 counterstained with alcian blue or with hematoxylin–eosin showed the absence of overlap between TCs and goblet cells, or between TCs and Paneth cells (Fig. 4A and B, Supplemental Fig. 4A). Double-fluorescence staining of mouse small intestine for pY1798 (n=24) and insulinoma-associated protein 1, a pan-neuroendocrine marker (n=36) also showed mutually exclusive distributions (Fig. 4C). Using double-fluorescence staining of mouse small intestine for pY1798 and sodium glucose transporter–1 (SGLT1, an enterocyte marker), we found that all pY1798-labeled TCs preserved cytosolic SGLT1. All epithelial cells with cytosolic SGLT1 were pY1798 positive (n=4), and all epithelial cells with SGLT1-positive brush borders were pY1798 negative (n=48; Fig. 4D), indicating that TCs in mouse small intestine express SGLT1, and that the subcellular distribution of SGLT1 is distinctly different between TCs and enterocytes. We next performed double-fluorescence staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) or Ki67 combined with pY1798 to investigate the proliferation profiles of TCs, as TCs are generally considered as post-mitotic, fully differentiated cells.6 As expected, this staining demonstrated that each proliferation marker strongly repelled pY1798 (Fig. 4E). Of note, we observed no epithelial cell double-positive for Ki67/pY1798 or PCNA/pY1798, indicating that pY1798-labeled TCs are non-proliferating epithelial cells. The postnatal appearance of TCs in rat salivary glands, rat common bile ducts, and mouse small intestine, during the ontogenic stage, has been previously reported.3,6,8 In harmony with these reports, pY1798-labeled TCs with their spool-shaped somas appeared at around postnatal day 7, whereas corresponding cells were not observed before postnatal day 5 (Supplemental Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

pY1798-positive cells are distinct from other minor epithelial cells. Immunohistochemistry of mouse jejunum with pY1798 antibodies, counterstained with alcian blue (A, left, low magnification, scale bar, 50 µm; right, high magnification of the boxed region, scale bar, 20 µm) or with hematoxylin–eosin (B, left, low magnification, scale bar, 100 µm; right, high magnification of the boxed region, scale bar, 20 µm). Neither goblet cells (black arrowheads) nor Paneth cells (red dotted circle) were pY1798 positive (open arrowheads). (C) Immunofluorescence of mouse jejunum with pY1798 antibodies and Insm1 (pan-neuroendocrine markers). pY1798-positive cells (white open arrowheads) and Insm1-positive cells (white closed arrowheads) were mutually exclusive (scale bars, 20 µm). (D) Immunohistochemistry (left) and immunofluorescence (right) of mouse jejunum with sodium glucose transporter 1 (SGLT1) antibodies. SGLT1 was found at the apical surfaces (black arrows) except for at the surface of goblet cells (red arrowhead). One cell (yellow arrowhead) is shown with a pY1798-positive signal in the cytoplasm (left). Cytoplasmic SGLT consistently colocalized with pY1798, whereas surface SGLT1 (white arrows) never did (right; scale bars, 10 µm). (E) Immunofluorescence of mouse jejunum with pY1798 antibodies and proliferation markers [Ki67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)]. From the left are shown pY1798 antibodies, proliferation marker (upper, Ki67, and lower, PCNA), and digitally merged images with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; scale bars, 20 µm).

Thus, by TEM and by double-staining, pY1798 was finally validated as a TC-marker in multiple gastrointestinal organs in mouse and human. More importantly, pY1798 antibodies exceeded any of the known TC-markers in staining intensity, staining specificity, and staining versatility (ability to stain multiple organs in multiple species), besides whole-cell visualization of the spool-shaped somas with characteristic signal condensation at each lumenal tip, representing the signature “tuft.”

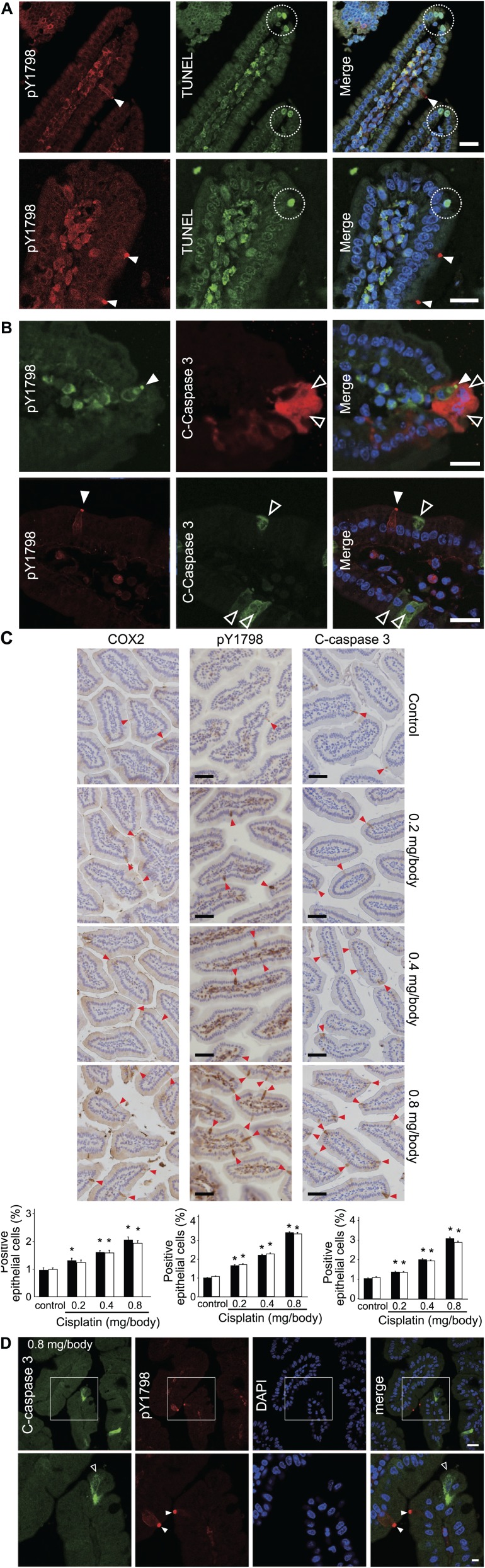

Lack of Apoptosis in TCs

The intestinal epithelium is highly dynamic tissue with continuous proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis, resulting in a complete renewal every 2 to 7 days.6 To understand how a TC eventually ends its life is an important question to fully elucidate the roles of TCs. In the villi of the mammalian small intestine, apoptosis of epithelial cells is known to occur at the villus tip.22 We therefore investigated if TCs were apoptotic using double-fluorescence staining for pY1798 and apoptotic markers, including TUNEL or cleaved caspase 3. Results showed that pY1798-labeled TCs and both apoptotic markers were consistently exclusive (Fig. 5A and B). The ORs, p values, and total counts for TUNEL and cleaved caspase 3 in mouse small intestine were infinity, 1, 136 and infinity, 1, 81, respectively. After we confirmed that no TCs were apoptotic in the basal state, we further tested the mutual exclusivity between pY1798 and cleaved caspase 3 under forced apoptotic conditions using mice treated with apoptotic inducers (cisplatin or X-ray irradiation). Surprisingly, lethal dose of cisplatin (0.8 mg/body) increased TC frequency within 24 hr by 3-fold (p<0.05) (Fig. 5C). Likewise, lethal dose of X-rays (15 Gy) increased TC frequency within 24 h by two-fold (p<0.05; Supplemental Fig. 5A). The sporadic distribution of TCs was maintained under forced apoptotic conditions; in other words, there were no TCs adjacent to each other. Despite the increase in apoptotic epithelial cells labeled with cleaved caspase 3 in mice treated with high-dose (0.8 mg/body) cisplatin, pY1798-labeled TCs consistently repelled apoptotic epithelial cells (Fig. 5D). Similarly, pY1798-labeled TCs consistently repelled apoptotic epithelial cells under 15 Gy X-rays (Supplemental Fig. 5B). Importantly, no epithelial cells double-positive for TUNEL/pY1798 nor for cleaved caspase 3/pY1798 were observed in any experiments. These observations revealed an unaccounted mutual exclusivity between TCs and apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Lack of apoptosis in tuft cells (TCs). (A) Double-fluorescence staining of mouse jejunum with TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and pY1798. TUNEL-positive cells (white dotted circles) at the villus tip and TCs (white closed arrowheads) were mutually exclusive (scale bars, 20 µm). (B) Immunofluorescence of mouse jejunum for pY1798 (left) and cleaved caspase 3 (C-caspase 3; right). C-Caspase 3–positive epithelial cells (white open arrowheads) and TCs (white closed arrowheads) were mutually exclusive (scale bars, 20 µm). (C) Apoptosis induction test using cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum or CDDP). Mice were divided into four groups (n=8 each): control, low-dose (0.2 mg/body), middle-dose (0.4 mg/body), and high-dose (0.8 mg/body), and euthanized for 24 or 48 hr after administration. Jejunum sections were stained for C-caspase 3, pY1798, or cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox2). The percentages of positive epithelial cells (red arrowheads) are summarized in bar graphs (24 hr, filled bars; 48 hr, open bars). *p<0.05 (scale bars, 50 µm). (D) Immunofluorescence of mouse jejunum for pY1798 and C-caspase 3 from the high-dose group. Boxed regions in the upper row (scale bars, 20 µm) are shown magnified below (scale bars, 5 µm). C-Caspase 3–positive epithelial cells (white open arrowheads) and TCs (white closed arrowheads) were mutually exclusive. Abbreviation: DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Discussion

By TEM and histological techniques with quantitative statistical analyses, we found phosphorylated Girdin at tyrosine-1798 (pY1798) to be a novel TC-marker in mammalian gastrointestinal tracts. The TEM image of pY1798-positive cells exhibited typical shapes of TCs. pY1798 and a known TC-marker co-existed in TCs. pY1798-positive TCs were non-proliferating cells, which were distinct from other minor epithelial cells, such as goblet, Paneth, and neuroendocrine cells. As far as we know, this is the first demonstration of characteristic phosphorylation in TCs. Moreover, this marker exceeded any previously known TC-marker in staining quality.7 For example, whole-cell visualization of TCs with pY1798 exceeded villin or phalloidin, which stains only the apexes of TCs, and pY1798 exceeded Cox2, DCLK1, and lectin UEA-I in staining contrast. Furthermore, pY1798 antibodies equally stained TCs across multiple organs in multiple species with characteristic morphological signatures, which authenticated pY1798-stained cells as TCs. We believe that pY1798 will serve future studies in the world by refining the analysis of TCs.

Using pY1798, we also revealed an unaccounted mutual exclusivity between TCs and apoptosis, both at baseline and under lethal doses of apoptosis inducers (cisplatin, or X-ray). Apoptosis inducers unexpectedly caused a large increase in the relative frequency of TCs in the mouse small intestine. This was a startling finding as TCs were completely non-proliferative (Ki67-negative and PCNA-negative) at baseline, and lethal doses of apoptosis inducers should have hindered TC proliferation. Of note, the sporadic distribution of TCs was maintained even under such forced apoptotic conditions, further suggesting that the proliferation of TCs was unlikely to account for the large increase in the relative frequency of TCs. One possible explanation is that TCs are resistant to apoptosis. In other words, the other epithelial cell types may be more sensitive to apoptosis inducers than TCs and therefore are reduced in number after 24 or 48 hr. However, even if we assume the resistance to apoptosis in TCs, it is still unknown whether it is sufficient to fully explain the large increase in the relative frequencies of TCs. We observed cytoplasmic SGLT1 in TCs, which suggests the role of enterocyte in explaining the increase in the relative TC frequencies (e.g., enterocyte to TC conversion by an unknown mechanism).

Our identification of the pY1798-specific labeling of TCs has substantially more scientific value than just as a novel TC-marker. It actually provided us with a good question about why Girdin is phosphorylated only in TCs and not in the neighboring enterocytes, which also seem to express Girdin. As shown in our previous study, tyrosine kinases (such as src, or ligand-activated EGF receptor) dynamically phosphorylated Girdin at Y1798 in vitro.20 We can therefore assume the activation of certain tyrosine kinases specifically in TC. Although the responsible tyrosine kinase for the phosphorylation of Y1798 is not known yet, it may not be ligand-activated receptor tyrosine kinase. Because any ligand usually forms a concentration gradient, that is inconsistent with the truly binary staining contrast (all or none) between TCs and non-TCs.

Besides this binary phosphorylation pattern and the non-apoptotic nature, there are many things that remain unaccounted around TCs. For example, first, it is well known that the nuclei of TCs are typically located closer to the lumen than those of enterocytes (deviation tendency). Second, we have never seen two TCs lying next to each other through this study (sporadic distribution). Third, TCs share spool-shaped somas by definition, and when viewed from the lumenal surface, TCs consistently possess small apical surfaces but are surrounded by cells with larger apical surface areas.7 Interestingly, Luciano and Reale23 described that the high frequencies of TCs in some organs were observed in regions close to sphincters (such as the esophageal sphincter for the gastric cardia, and the sphincter Oddi for the distal region of choledochus duct), and the authors attributed the biased distribution of TCs to the pressure variation across the intraluminal epithelium. Meanwhile, two groups independently revealed the existence of phosphorylated Girdin in focal adhesions in cultured cell-lines,20,24 which implied the relationship between the mechanical force and the phosphorylation of Girdin. If we assume the mechanical force acting on a TC is the primary cause of the kinase activation, it may have the potential to account nicely for these mysteries around TCs (non-apoptotic nature, binary pY1798 pattern, deviation tendency, sporadic distribution, and small apical surface). However, so far, it has been difficult to prove or disprove our hypothesis due to the technical limitations.

As a promising new area of TC research pertaining to human health, we are interested in a recent work in which the authors suggest that long-lived intestinal TCs serve as colon-cancer initiating cells.25 Colon-cancer initiation and the phosphorylation mechanism of Girdin Y1798 may have common kinases in TCs. Technical innovations, such as long-term imaging of a single intestinal epithelial cell in vivo, or rigorously TC-specific Cre-recombinase expressing mouse lines, are required for a much deeper understanding of TCs.

In conclusion, pY1798 is a novel TC-marker enabling visualization of characteristic morphology. Selective tyrosine phosphorylation and possible resistance to apoptosis inducers implied the activation of certain kinase(s) in TCs, which may become a clue to elucidate the enigmatic roles of TCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Joachim and Joseph A. Majzoub at Harvard University for providing technical support in animal experiments, Yoshikazu Fujita and Koji Itakura at Nagoya University for transmission electron microscopy, Yosuke Iwata at Ogaki Municipal Hospital for providing scientific suggestions, Edward M. Levine and Lewis Charles Murtaugh at the University of Utah for expertise regarding Hes1-Cre-ERT2 mice, and Toyoshi Fujimoto and Shigeko Torihashi for helpful discussions regarding tuft cells.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: MA designed the study; MA and DK wrote the manuscript; all authors edited the manuscript; MA and DK performed the immunofluorescence; DK, KU and MA performed the immunohistochemistry; DK performed the transmission-electron-microscopy; DK and MA conducted the animal experiments; DK and MA performed the statistical analyses; All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan; A-STEP from the Japan Science and Technology Agency 2014 (AS251Z02522Q) and 2015 (AS262Z00715Q); a Takeda Visionary Research Grant 2014 from the Takeda Science Foundation (to MA); a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) and (S); and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan (to MT).

Literature Cited

- 1. Jarvi O, Keyrilainen O. On the cellular structures of the epithelial invasions in the glandular stomach of mice caused by intramural application of 20-methylcholantren. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1956;39(Suppl 111):72–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sato A. Tuft cells. Anat Sci Int. 2007;82:187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sato A, Hamano M, Miyoshi S. Increasing frequency of occurrence of tuft cells in the main excretory duct during postnatal development of the rat submandibular gland. Anat Rec. 1998;252:276–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rhodin J, Dalhamn T. Electron microscopy of the tracheal ciliated mucosa in rat. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1956;44:345–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hofer D, Asan E, Drenckhahn D. Chemosensory perception in the gut. News Physiol Sci. 1999;14: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gerbe F, Van Es JH, Makrini L, Brulin B, Mellitzer G, Robine S, Romagnolo B, Shroyer NF, Bourgaux J-F, Pignodel C. Distinct ATOH1 and Neurog3 requirements define tuft cells as a new secretory cell type in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:767–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerbe F, Legraverend C, Jay P. The intestinal epithelium tuft cells: specification and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2907–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iseki S. Postnatal development of the brush cells in the common bile duct of the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;266:507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howitt MR, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Blum AM, Tran SV, Weinstock JV, Gallini CA, Redding K, Margolskee RF, Osborne LC, Artis D, Garrett WS. Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science. 2016;351:1329–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Dardalhon V, Cesses P, Garnier L, Pouzolles M, Brulin B, Bruschi M, Harcus Y, Zimmermann VS, Taylor N, Maizels RM, Jay P. Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature. 2016;529:226–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Enomoto A, Murakami H, Asai N, Morone N, Watanabe T, Kawai K, Murakumo Y, Usukura J, Kaibuchi K, Takahashi M. Akt/PKB regulates actin organization and cell motility via Girdin/APE. Dev Cell. 2005;9:389–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le-Niculescu H, Niesman I, Fischer T, Devries L, Farquhar MG. Identification and characterization of GIV, a novel Galpha i/s-interacting protein found on COPI, endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi transport vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22012–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simpson F, Martin S, Evans TM, Kerr M, James DE, Parton RG, Teasdale RD, Wicking C. A novel hook-related protein family and the characterization of hook-related protein 1. Traffic. 2005;6:442–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kitamura T, Asai N, Enomoto A, Maeda K, Kato T, Ishida M, Jiang P, Watanabe T, Usukura J, Kondo T. Regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB substrate Girdin. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Enomoto A, Asai N, Namba T, Wang Y, Kato T, Tanaka M, Tatsumi H, Taya S, Tsuboi D, Kuroda K, Kaneko N, Sawamoto K, Miyamoto R, Jijiwa M, Murakumo Y, Sokabe M, Seki T, Kaibuchi K, Takahashi M. Roles of disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1-interacting protein girdin in postnatal development of the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2009;63:774–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Y, Kaneko N, Asai N, Enomoto A, Isotani-Sakakibara M, Kato T, Asai M, Murakumo Y, Ota H, Hikita T, Namba T, Kuroda K, Kaibuchi K, Ming GL, Song H, Sawamoto K, Takahashi M. Girdin is an intrinsic regulator of neuroblast chain migration in the rostral migratory stream of the postnatal brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8109–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asai M, Asai N, Murata A, Yokota H, Ohmori K, Mii S, Enomoto A, Murakumo Y, Takahashi M. Similar phenotypes of Girdin germ-line and conditional knockout mice indicate a crucial role for Girdin in the nestin lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;426:533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin C, Ear J, Pavlova Y, Mittal Y, Kufareva I, Ghassemian M, Abagyan R, Garcia-Marcos M, Ghosh P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Gα-interacting protein GIV promotes activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase during cell migration. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goto H, Inagaki M. Production of a site- and phosphorylation state-specific antibody. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Omori K, Asai M, Kuga D, Ushida K, Izuchi T, Mii S, Enomoto A, Asai N, Nagino M, Takahashi M. Girdin is phosphorylated on tyrosine 1798 when associated with structures required for migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gebhard A, Gebert A. Brush cells of the mouse intestine possess a specialized glycocalyx as revealed by quantitative lectin histochemistry. Further evidence for a sensory function. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams JM, Duckworth CA, Burkitt MD, Watson AJ, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM. Epithelial cell shedding and barrier function: a matter of life and death at the small intestinal villus tip. Vet Pathol. 2015;52:445–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luciano L, Reale E. Brush cells of the mouse gallbladder. A correlative light- and electron-microscopical study. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;262:339–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lopez-Sanchez I, Kalogriopoulos N, Lo IC, Kabir F, Midde KK, Wang H, Ghosh P. Focal adhesions are foci for tyrosine-based signal transduction via GIV/Girdin and G proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:4313–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Westphalen CB, Asfaha S, Hayakawa Y, Takemoto Y, Lukin DJ, Nuber AH, Brandtner A, Setlik W, Remotti H, Muley A, Chen X, May R, Houchen CW, Fox JG, Gershon MD, Quante M, Wang TC. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1283–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.