Abstract

Background and aim

The efficacy of clipping for preventing delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic resection is still controversial. To assess the efficacy of prophylactic clipping, we conducted a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Methods

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane library, and the Igaku-chuo-zasshi database for randomized trials eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis. We identified seven eligible randomized trials from the database search, and compared the effect of clipping versus non-clipping with respect to delayed bleeding and perforation. Data from eligible studies were combined to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs).

Results

Postoperative bleeding was observed in 41 of 1526 cases (2.7%) without clipping and in 32 of 1533 cases (2.1%) with clipping (OR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.39–1.47, p = 0.414). There was no significant heterogeneity among the trial results (I-Square = 26.7%, p = 0.22). In the subgroup analysis based on small tumor size (<20 mm) and large tumor size (≥20 mm), there were no significant differences. Compared with non-clipping, the pooled OR of developing perforation with clipping was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.14–7.25), indicating no significant difference between the two groups.

Conclusions

Prophylactic clipping did not decrease the occurrence of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic resection. Clipping could be of interest in patients with a high risk of bleeding (anticoagulation) or large lesions, but with the available trials data to prove this are scarce.

Keywords: Clip, endoscopic resection, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, bleeding

Introduction

The most common major complication of endoscopic resection for colorectal tumors is bleeding. The incidence of bleeding after endoscopic resection was reported to be approximately 1–6% of polypectomies.1 Closure of the mucosal defect after endoscopic resection using endoscopic clips could be expected to reduce delayed bleeding. Several large retrospective studies showed prophylactic clipping to be beneficial for preventing delayed bleeding.2,3

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have investigated the efficacy of prophylactic clipping for preventing delayed bleeding, with contradictory results.4-10 We propose that systematic pooling of all data from available studies might provide better insight into the efficacy of prophylactic clipping. Our objective was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs, with the outcome of comparing the efficacy of prophylactic clipping for colorectal endoscopic resection.

Methods

Before performing meta-analysis, we developed a simplified protocol for search strategies, a specific criterion for selection of studies, methods for extraction of relevant data, and strategies for assessment of study quality, and statistical analysis.

Search strategy

The electronic databases PubMed, the Cochrane library, and the Igaku-chuo-zasshi database of Japan (from 1950 to September 2016) were used for the systematic literature search. A search strategy was constructed using a combination of the following words: (clip) AND (endoscopic) AND (colorectal or colonic) AND (randomized). Articles published in any language were included.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) study type: RCT; (2) population: patients undergoing endoscopic resection for colorectal tumors; (3) intervention: active treatment with clipping; (4) comparator: non-clipping; (5) outcome: delayed postoperative bleeding and perforation. Duplicate publications and reviews were excluded.

Data extraction

Standardized data abstraction sheets were prepared. Extracted data included study design, study quality, intervention, and outcomes. The outcome measures examined were “delayed postoperative bleeding” and “perforation”. Delayed postoperative bleeding included either clinically relevant or endoscopically evident bleeding. We contacted the corresponding authors in order to clarify detail of studies. All articles were examined independently for eligibility by two reviewers (TN and HS). Disagreements were resolved by consultation with a third reviewer (OG).

Assessment of methodology quality

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the risk-of-bias tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0). Two reviewers (TN and HS) reviewed all studies and assessed six different key aspects that might influence the quality of a RCT, including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, outcome assessors, management of eventual incomplete outcome data, completeness of outcome reporting, and other confounding factors that could potentially undermine the validity of the data.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into the StatsDirect statistical package (StatsDirect Ltd., Cheshire, UK). Separate analyses were performed for each outcome using an odds ratio (OR). We used a random-effect model to calculate summary ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We always used a random-effect model, regardless of the significance of the heterogeneity.11–13 Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by Cochran’s Q and I-squared tests. Because of the low power of the Q test, a cut-off value of less than 0.10 was used to reject homogeneity, which thereby indicated heterogeneity. An I-squared score of ≥50% indicates more than moderate heterogeneity. For studies in which no complication was observed, a value of 0.5 was used instead of 0 to facilitate calculation of the ORs of individual studies.14–16 However, this addition had no impact on the estimation of the pooled ORs. An analysis of sensitivity was performed in order to evaluate the stability of the results. The subgroup analyses were performed considering <20 mm and ≥20 mm lesion size, and pedunculated and non-pedunculated type of morphology. Finally, we used funnel plot asymmetry to detect any publication bias in the meta-analysis, and Egger’s regression test to measure funnel plot asymmetry.

Results

Search results

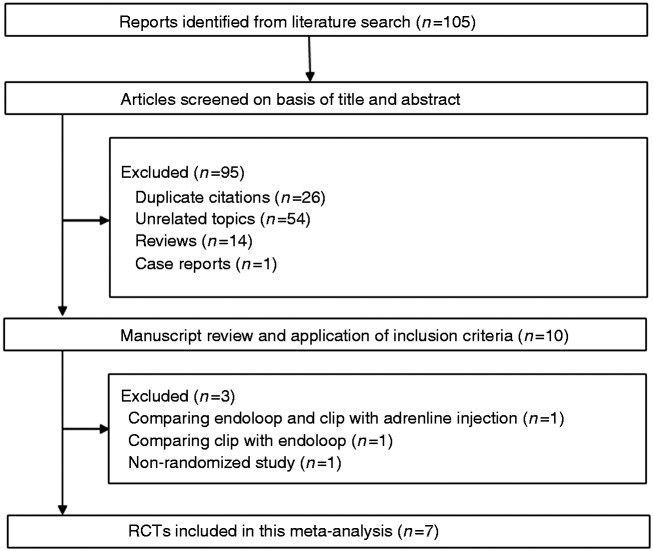

Our database search yielded a total of 105 citations (Figure 1). Of these, 95 studies were removed from consideration after reviewing the abstracts, based on the exclusion criteria (26 duplicates, 54 unrelated topics, 14 reviews, and one case report). The remaining 10 studies were examined in detail. A further three studies were then excluded due to comparison of endoloop and clip with adrenaline injection (n = 1),17 comparison of clip with endoloop (n = 1),18 and lack of randomization comparison (n = 1).3 Finally, seven studies were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of RCTs included in the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author | Country | Endoscopic resection | Inclusion criteria for lesion size | Definitions of delayed bleeding | Allocation | Immediate bleeding | Patients number | Number of polyps | Age ± SD | Gender M/F | Lesion size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||||||||

| Shioji | Japan | EMR | 5–30 mm | Hematochezia and endoscopic confirmation | Clip | Excluded | 156 | 206 | 64 ± 9 | 118/38 | 7.8 ± 3.9 mm* |

| 2003 | Non-clip | Excluded | 167 | 208 | 63 ± 12 | 130/37 | 7.8 ± 4.1 mm* | ||||

| Tominaga | Japan | EMR | >5 mm | Endoscopic hemostasis is required | Clip | Excluded | 211 | 385 | 67.0 (22–88)† | 151/60 | 7.7 (5–30) mm† |

| 2014 | Non-clip | Excluded | 216 | 416 | 66.6 (15–94)† | 148/68 | 8.5 (5–35) mm† | ||||

| Mori | Japan | EMR | 10–20 mm | Bleeding symptom | Clip | Clip | – | 73 | – | – | 15.3 ± 2.8 mm* |

| 2015 | 1–7 days after EMR | Snare cauterization | Snare cauterization | – | 73 | – | – | 15.5 ± 2.6 mm* | |||

| Dokoshi | Japan | EMR or | – | Anal bleeding, hemoglobin loss | Clip | – | – | 154 | 67.1 ± 8# | 109/45 | <10 mm: 64%, 10–20 mm: 31%, ≥20 mm: 5% |

| 2015 | polypectomy | (≥2 g/dl) and endoscopic confirmation | Non-clip | – | – | 134 | 67.8 ± 11# | 99/35 | <10 mm: 64%, 10–20 mm: 31%, ≥20 mm: 5% | ||

| Zhang | China | EMR or | 10–40 mm | Hematochezia 6 hours to 30 days afetr | Clip | Electocoagulation | 174 | 174 | 67.9 ± 12.6 | 112/62 | 10–20 mm: 64%, 20–40 mm: 36% |

| 2015 | ESD | treatment and endoscopic confirmation | Non-clip | Electocoagulation | 174 | 174 | 64.2 ± 9.8 | 107/67 | 10–20 mm: 62%, 20–40 mm: 38% | ||

| Osada | Japan | ESD | 20–50 mm | Overt rectal bleeding | Clip | Electocoagulation | 13 | 13 | 68.8 ± 8.7 | 9-4 | 677 ± 306 mm2* |

| 2016 | during 4 weeks | Non-clip | Electocoagulation | 13 | 13 | 66.2 ± 10.4 | 7–6 | 790 ± 221 mm2* | |||

| Matsumoto | Japan | EMR or | <20 mm | Bloody stools or hemoglobin loss | Clip | Excluded | 752 | 1636 | 65 (25–87)† | 534/218 | <5 mm: 24%, 5–20 mm: 76% |

| 2016 | polypectomy | (≥2 g/dl), then endoscopic confirmation | Non-clip | Excluded | 747 | 1728 | 66 (25–88)† | 513/234 | <5 mm: 26%, 5–20 mm: 74% |

EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; SD, standard deviation

#Standard error

Range

±SD

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the RCTs is shown in Table 2. In general, the included trials had a low risk of bias. All seven RCTs described the specific methods used for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Blinding was not performed in any of the seven RCTs. All seven RCTs were found to adequately assess incomplete outcomes, avoid selective outcome reporting, and were free of other biases. None of the RCTs described the use or not of CO2.

Table 2.

Evaluation of bias of RCTs included in the meta-analysis.

| First author | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Adequate assessment of incomplete outcome | Selective reporting avoided | No other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shioji | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tominaga | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mori | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dokoshi | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhang | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Osada | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Matsumoto | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Yes: Low risk of bias

No: High risk of bias

Unclear: Unclear risk of bias

Meta-analysis results

Postoperative bleeding

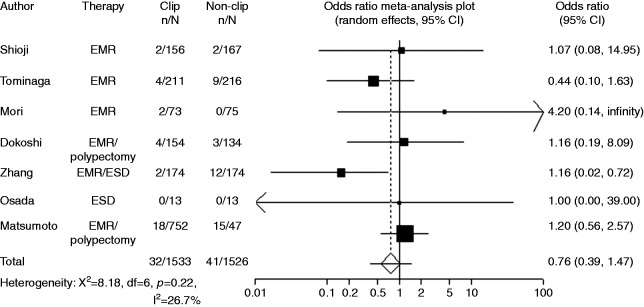

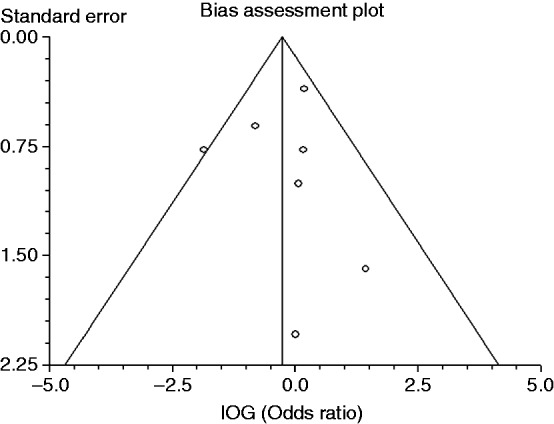

Postoperative bleeding was recorded in seven studies. While most of the studies reported number of patients in clipping group and non-clipping groups, Mori et al. and Dokoshi et al. reported numbers of polyps in clipping group and non-clipping groups. Owing to the limited number of reports, studies with different criteria were combined in the present meta-analysis. When the data were pooled, postoperative bleeding was observed in 41 of 1526 cases (2.7%) without clipping and in 32 of 1533 cases (2.1%) with clipping (OR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.39–1.47, p = 0.414) (Figure 2, Table 3). There was no significant heterogeneity among the trial results (I-Square = 26.5%, p = 0.23). The sensitivity analysis performed using sequential excluding of one trial at a time did not alter the results. Results of the Egger test suggested no significant asymmetry of the funnel plot (p = 0.85), indicating no evidence of substantial publication bias (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot displaying the odds ratio and 95% CIs of each study for delayed bleeding.

Table 3.

The outcome of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author Year | Endoscopic resection | Allocation | Patients number | Delayed bleeding | Perforation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shioji | EMR | Clip | 156 | 2 | – |

| 2003 | Non-clip | 167 | 2 | – | |

| Tominaga | EMR | Clip | 211 | 4 | – |

| 2014 | Non-clip | 216 | 9 | – | |

| Mori | EMR | Clip | 73# | 2 | 0 |

| 2015 | Snare cauterization | 73# | 0 | 0 | |

| Dokoshi | EMR or | Clip | 154# | 4 | – |

| 2015 | polypectomy | Non-clip | 134# | 3 | – |

| Zhang | EMR or | Clip | 174 | 2 | 1 |

| 2015 | ESD | Non-clip | 174 | 12 | 1 |

| Osada | ESD | Clip | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | Non-clip | 13 | 0 | 0 | |

| Matsumoto | EMR or | Clip | 752 | 18 | – |

| 2016 | polypectomy | Non-clip | 747 | 15 | – |

#Number of polyps

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of the included studies.

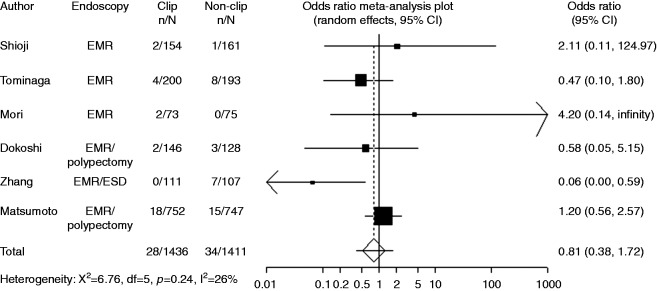

Six trials with available data on small tumor size (<20 mm) included 1436 cases with clipping and 1411 cases without clipping. Compared with non-clipping, the pooled OR for delayed postoperative bleeding with clipping was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.38–1.72), indicating no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 4). Four trials with available data on large tumor size (≥20 mm) included 97 cases with clipping and 115 cases without clipping. Compared with non-clipping, the pooled OR for delayed postoperative bleeding with clipping was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.23–2.68), indicating no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Forest plot displaying the odds ratio and 95% CIs of each study for delayed bleeding with small tumor size (<20 mm).

Figure 5.

Forest plot displaying the odds ratio and 95% CIs of each study for delayed bleeding with large tumor size (≥20 mm).

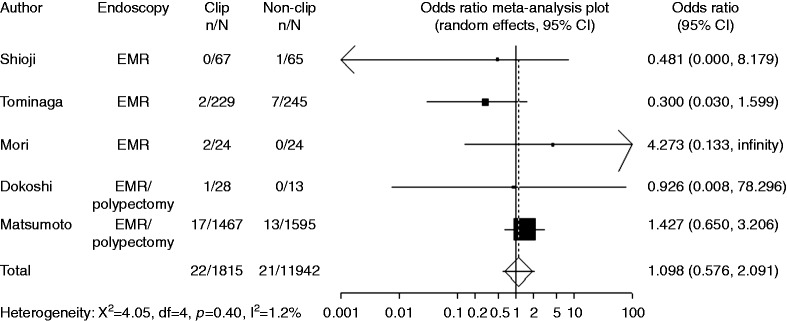

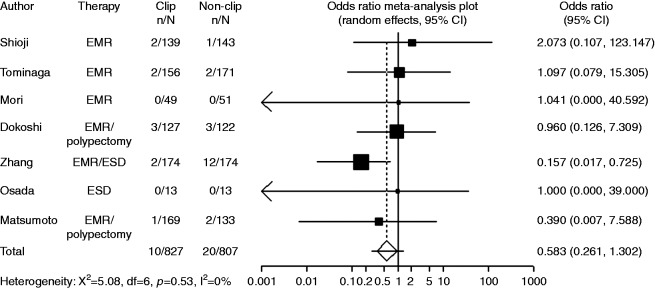

In the subgroup analyses of pedunculated and non-pedunculated type, numbers of polyps in clipping group and non-clipping group were reported instead of numbers of patients in each study. Five trials with available data on pedunculated type included 1815 polyps with clipping and 1942 polyps without clipping. Compared with non-clipping, the pooled OR for delayed postoperative bleeding with clipping was 1.10 (95% CI: 0.58–2.09), indicating no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 6). Five trials with available data on non-pedunculated type included 827 polyps with clipping and 807 polyps without clipping. Compared with non-clipping, the pooled OR for delayed postoperative bleeding with clipping was 0.58 (95% CI: 0.26–1.30), indicating no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Forest plot displaying the odds ratio and 95% CIs of each study for delayed bleeding with pedunculated type.

Figure 7.

Forest plot displaying the odds ratio and 95% CIs of each study for delayed bleeding with non- pedunculated type.

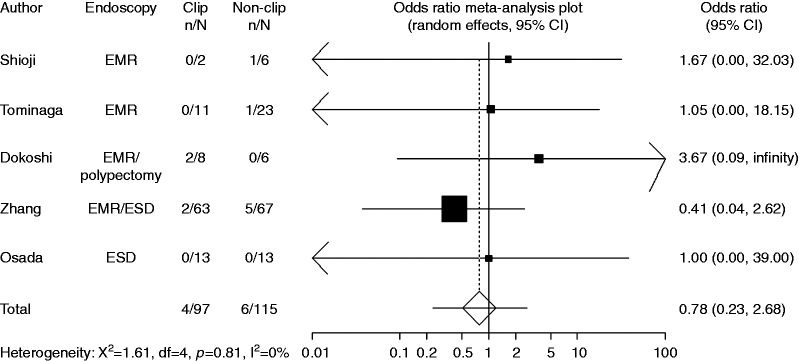

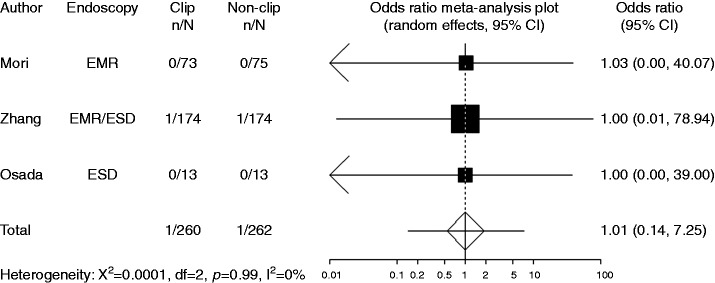

Perforation

Perforation was recorded in three studies. In these studies, the definition of perforation was free air recognized by X-ray or CT scanning. Compared with non-clipping, the pooled OR of developing perforation when clipping was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.14–7.25), indicating no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Forest plot displaying the odds ratio and 95% CIs of each study for perforation.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis revealed no significant effect of prophylactic clipping for preventing delayed bleeding after the endoscopic resection of colorectal tumors.

In this meta-analysis, the efficacy of prophylactic clipping was evaluated with respect to tumor size (>20 mm) or pedunculated type. There were no significant differences between clipping group and non-clipping group with regard to large tumor size or pedunculated type. However, because only a few trials were included, these results should be interpreted with caution, and more studies are needed.

Theoretically, the placement of prophylactic clips to avoid delayed bleeding may seem attractive and safe. However, prophylactic clips may cause bleeding when they disengage. In the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES) guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection (ESD/EMR), postoperative clipping is suggested to be effective to some extent for patients with a high risk of postoperative hemorrhage, those with large lesions, or those who had undergone antithrombotic therapy in EMR.19 The level of evidence is IVb (analytical epidemiologic study: case-control study, cross-sectional study), and relatively low. The necessity for prophylactic clipping after endoscopic resection has been empirically judged by individual physicians or institutes.

In view of health economics, the cost of one clip is approximately 787.5 yen (USD 7.9).20 In the study by Matsumoto et al., an average of 1.56 ± 0.97 clips were required in the clipping group. Thus, if no clipping is done, 1228 yen (USD 12.3) could be saved per polyp.10

Prophylactic clipping is time-consuming. In the study by Dokoshi et al. the length of the procedure was significantly longer in the clipping group (528 ± 559 seconds) than in the non-clipping group (281 ± 263 seconds).7

The retrospective study of Liaquat et al. showed prophylactic clipping after polypectomy (mean polyp size: 31 mm) to be beneficial for preventing delayed bleeding.3 This retrospective study showed an advantage of clipping, but bias include the retrospective nature of the study and the effect of time/increased experience, as well as the fact that high-risk patients were included (anticoagulation), perhaps leaving a role for endoscopic clipping in these patients.

The present meta-analysis has several limitations. First, most study participants were Japanese and Chinese, so the results may not be generalizable to other races. Second, the risk of bias imposed by the lack of blinding in all seven RCTs must be considered. We integrated the results of all relevant individual RCTs; however, our conclusions were still based on a relative small number of trials. In particular, the patient number on large tumor size ( ≥ 20 mm) was small. This study might therefore be underpowered and may fail to detect unrevealed but statistically important differences. Immediate bleedings after endoscopic resection were excluded from three RCTs. Antiplatelet therapy was stopped from 3–7 days before endoscopic resection in five RCTs, and patients who took antithrombotic drugs were excluded from one RCT. Therefore, it may be necessary to perform prophylactic clipping in patients with a high risk of bleeding.

In conclusion, prophylactic clipping did not decrease the occurrence of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic resection. Clipping could have a use in patients with a high risk of bleeding (anticoagulation) or large lesions, but data are scarce to prove this with the available trials.

Declaration of conflicting interests

During the last two years, HS received scholarship funds for the research from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd and received service honoraria from Astellas Pharm Inc., Astra-Zeneca KK, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Mylan EPD, Co. and Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. TK received scholarship funds for the research from Astellas Pharm Inc., Astra-Zeneca KK, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Eisai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, JIMRO Co. Ltd, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and received service honoraria from Astellas Pharm Inc., Eisai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, JIMRO Co. Ltd, Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Miyarisan Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. NY received scholarship funds for the research from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Eisai Co, Kaigen Pharm Co. Ltd, Boston Scientific Japan KK, Nihon Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Hoya corporation and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. OH received scholarship funds for the research from Mochida Seiyaku Co., Ltd. JIMRO Co. Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Limited, Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co. Limited, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Astellas Pharma Inc, Eisai Co. Ltd, Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Astra-Zeneca KK, and Boston Scientific Japan KK. The funding source had no role in the design, practice or analysis of this study. There are no other conflicts of interests for this article.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (16H05291, to HS), MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (S1411003, to HS) and Keio Gijuku Academic Development Funds (to HS).

References

- 1.Gibbs DH, Opelka FG, Beck DE, et al. Postpolypectomy colonic hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39(7): 806–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto M, Fukunaga S, Saito Y, et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic resection for large colorectal tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012; 42(11): 1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liaquat H, Rohn E, Rex DK. Prophylactic clip closure reduced the risk of delayed postpolypectomy hemorrhage: Experience in 277 clipped large sessile or flat colorectal lesions and 247 control lesions. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 77(3): 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shioji K, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Prophylactic clip application does not decrease delayed bleeding after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 57(6): 691–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tominaga N, Tanaka Y, Higuchi T, et al. The effect of hemostasis clipping post endoscopic mucosal resection of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterol Endosc 2014; 56(1): 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, et al. Simple and reliable treatment for post-EMR artificial ulcer floor with snare cauterization for 10- to 20-mm colorectal polyps: A randomized prospective study (with video). Surg Endosc 2015; 29(9): 2818–2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dokoshi T, Fujiya M, Tanaka K, et al. A randomized study on the effectiveness of prophylactic clipping during endoscopic resection of colon polyps for the prevention of delayed bleeding. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 490272–490272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang QS, Han B, Xu JH, et al. Clip closure of defect after endoscopic resection in patients with larger colorectal tumors decreased the adverse events. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 82(5): 904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osada T, Sakamoto N, Ritsuno H, et al. Closure with clips to accelerate healing of mucosal defects caused by colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc 2016; 30(10): 4438–4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto M, Kato M, Oba K, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled study to assess the effect of prophylactic clipping on post-polypectomy delayed bleeding. Dig Endosc 2016; 28(5): 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Akimoto T, et al. Effects of preoperative proton pump inhibitor administration on bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J 2016; 4(1): 5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Sagara S, et al. Dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for gastrointestinal endoscopy: A meta-analysis. Dig Endosc 2015; 27(1): 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Fujimoto A, et al. Effects of carbon dioxide insufflation in balloon-assisted enteroscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J 2016; 4(1): 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qadeer MA, Vargo JJ, Khandwala F, et al. Propofol versus traditional sedative agents for gastrointestinal endoscopy: A meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3(11): 1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, et al. Propofol versus traditional sedative agents for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc 2014; 26(6): 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Kinoshita S, et al. Second-look endoscopy after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms. Dig Endosc 2015; 27(3): 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouklakis G, Mpoumponaris A, Gatopoulou A, et al. Endoscopic resection of large pedunculated colonic polyps and risk of postpolypectomy bleeding with adrenaline injection versus endoloop and hemoclip: A prospective, randomized study. Surg Endosc 2009; 23(12): 2732–2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji JS, Lee SW, Kim TH, et al. Comparison of prophylactic clip and endoloop application for the prevention of postpolypectomy bleeding in pedunculated colonic polyps: A prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Endoscopy 2014; 46(7): 598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, et al. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc 2015; 27(4): 417–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizawa T, Ochiai Y, Uraoka T, et al. Endoscopic slip knot clip suturing method: A prospective pilot study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc in . press. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]