Abstract

Background and aim

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication regimen has not been standardized for patients with penicillin allergy. We investigated the association between the efficacy of a 10-day sitafloxacin, metronidazole, and esomeprazole triple regimen and antibiotic resistance, in patients with penicillin allergy.

Methods

Penicillin-allergic patients infected with H. pylori were enrolled between March 2014 and November 2015. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of sitafloxacin and metronidazole, and the gyrA mutation status of the H. pylori strains were determined before treatment. The cut-off points for antimicrobial resistance were defined as 8.0 µg/ml for metronidazole and 0.12 µg/ml for sitafloxacin. The patients received the triple therapy (20 mg esomeprazole, bid; 250 mg metronidazole, bid; and 100 mg sitafloxacin, bid) for 10 days. Successful eradication was evaluated using the [13C] urea breath test or the H. pylori stool antigen test.

Results

Fifty-seven patients were analyzed, and the overall eradication rate was 89.5%. The eradication rate in cases of double antibiotic resistance to metronidazole and sitafloxacin was 40.0%, whereas for other combinations of resistance, this was above 90.0%. Finally, the eradication rate of gyrA mutation-negative strains was 96.2%, whereas for gyrA mutation-positive strains, it was 83.9%. Adverse events were reported in 31.6% of cases, all of which were mild and tolerable.

Conclusion

Ten days of sitafloxacin and metronidazole triple therapy was safe and highly effective in eradicating H. pylori in penicillin-allergic patients. Double resistance to metronidazole and sitafloxacin was an important predicting factor for eradication failure. However, 10 days of the sitafloxacin and metronidazole triple therapy was highly effective if the strain was susceptible to either sitafloxacin or metronidazole.

Keywords: Sitafloxacin, gyrA, metronidazole, penicillin allergy

Introduction

Although penicillin is a key drug for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication,1 penicillin allergy is the most common drug allergy.2 The prevalence of penicillin allergy is reported to be 1% to 12%, depending on the evaluated population.3 For penicillin-allergic patients with H. pylori infection, a clarithromycin (CLR) and metronidazole (MTZ) triple regimen is the most commonly used regimen for eradication; however, the reported eradication rates were insufficient (55%–59%).4–6 Similarly, the reported eradication rates using tetracycline, MTZ, and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) (+bismuth) were poor (53%–85%).4,6,7 Conversely, fluoroquinolone-containing regimens appear to be more successful. Gisbert et al. reported H. pylori eradication in 73% (11/15) of cases, using CLR and levofloxacin (LVFX)-containing triple therapy (a second-line regimen for penicillin-allergic patients) for 10 days.5 Thus, a fluoroquinolone-containing triple is confirmed as an option in the presence of penicillin allergy in the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report.8 On the other hand, Canadian guidelines recommended that quinolones should not be used unless necessary to eradicate H. pylori.9 In any case, the relationship between antibiotic resistance and successful eradication has not been sufficiently evaluated, and hence is the rationale for this study.

In fact, we reported that the eradication rates of gyrA mutation-negative and -positive strains treated with 10 days of sitafloxacin (STFX) and metronidazole (MTZ)-containing triple regimen (as third-line therapy) were 100% (16/16) and 66.7% (26/39), respectively.10 Considering that there were participants for whom the third-line, MTZ-containing therapy failed at least once in our previous study,10 the effectiveness of this 10-day STFX and MTZ-containing triple regimen in penicillin-allergic patients could be anticipated.

Antibiotic resistance is an important factor for H. pylori eradication; however, there are no previous studies evaluating the relationship between antibiotic resistance and eradication success in penicillin-allergic patients. Therefore, we assessed the influence of antibiotic resistance on successful H. pylori eradication in this patient group, using 10 days of STFX and MTZ-containing triple therapy.

Materials and methods

Study population

This was a prospective and nonrandomized study conducted at Keio University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan). The protocol for this study was approved by the ethics committee of the Keio University School of Medicine (no. 20130418; February 10, 2014) and registered in the University hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000013195 (http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/)). Patients who had a documented allergy to penicillin, or had experienced an allergic reaction caused by the amoxicillin-containing H. pylori eradication treatment, were enrolled. They also had an H. pylori infection at the time of enrollment, as confirmed using the [13C] urea breath test (UBT), or the H. pylori stool antigen test (HpSA).11 Patients were excluded if they had a documented allergy to fluoroquinolones or PPIs, or if they had severe renal or hepatic failure; they were also excluded if they were pregnant. Participants were enrolled after obtaining written informed consent.

Study design

H. pylori isolates were obtained from gastric biopsy specimens before the start of treatment. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of STFX, CLR, and MTZ against H. pylori isolates, and the gyrA mutation status of the H. pylori strains, were determined.12,13 The patients who refused esophagogastroduodenoscopy after giving informed consent and the H. pylori culture-negative patients were excluded from the intention-to-treat population (ITT population). After confirming H. pylori infection with the culture method, the patients received triple therapy (20 mg esomeprazole, bid (twice daily); 250 mg MTZ, bid; and 100 mg STFX, bid) for 10 days.10 The patients who refused to receive the eradication treatment after giving informed consent were excluded from the ITT population. Twelve weeks after the end of eradication therapy, successful eradication was confirmed using UBT or HpSA.11 The cut-off value for a negative UBT was <2.5%.14

Susceptibility of H. pylori to antimicrobial agents

The MICs defining the antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori were 1.0 µg/ml for CLR and 8.0 µg/ml for MTZ, in accordance with previous reports.10,13 For STFX, however, the MIC was defined as 0.12 µg/ml, based on our previous report.13

Detection of gyrA mutation

To determine the gyrA mutation status, we isolated of H. pylori chromosomal and plasmid DNA using previously described methods.15 Then, we amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequenced the “quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR)” of gyrA (from codon 38 to 154) gene; gyrA (forward), 5′-TTTRGCTTATTCMATGAGCGT-3′; gyrA (reverse), 5′-GCAGACGGCTTGGTARAATA-3′. PCR was performed with 35 cycles of denaturation at 94℃ for 30 seconds, annealing at 52℃ for 30 seconds, and extension at 72℃ for one minute.12,13,16 PCR products for sequencing were purified with a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). PCR templates of all strains were sequenced directly on both strands by the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing method using Applied Biosystems 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences obtained were compared with the published sequences of the H. pylori gyrA gene (GenBank accession no. L29481).17

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measures were the eradication rates of MTZ and STFX-susceptible or -resistant H. pylori strains. The secondary outcome measures included the eradication rates of gyrA mutation-positive or -negative H. pylori strains, the other factors associated with eradication success, and the frequency of adverse events.

Treatment compliance and adverse events

Patients were interviewed regarding adverse events one week after the completion of therapy. Treatment adherence was evaluated by counting the leftover tablets at the end of the regimen. Poor compliance was defined as an intake of <80% of the study drugs.10,18

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between the factors affecting eradication rate were conducted with the Fisher’s exact test, the Pearson's chi-square test, and the Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Multiple comparison with residual analysis was carried out to investigate if the data obtained using Pearson’s chi-square test were significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

Sample size and study conduct

According to a previous 10-day MTZ and STFX triple therapy for third-line treatment, the eradication rate was 72.4%.10 Thus, we assumed an eradication rate of 80.0% as an expected value in this study because almost of the enrolling patients will receive eradication for the first or second time. Based on an α-error of 0.05, a power of 0.80 to detect a significant difference and expected threshold eradication rate of 66%, we determined that 64 participants were needed for this study with hypothesis testing of binomial distribution. We estimated the failure rate for H. pylori isolation would be 10%. Therefore, more than 70 participants needed to be recruited to participate in this study.

Results

Patient characteristics

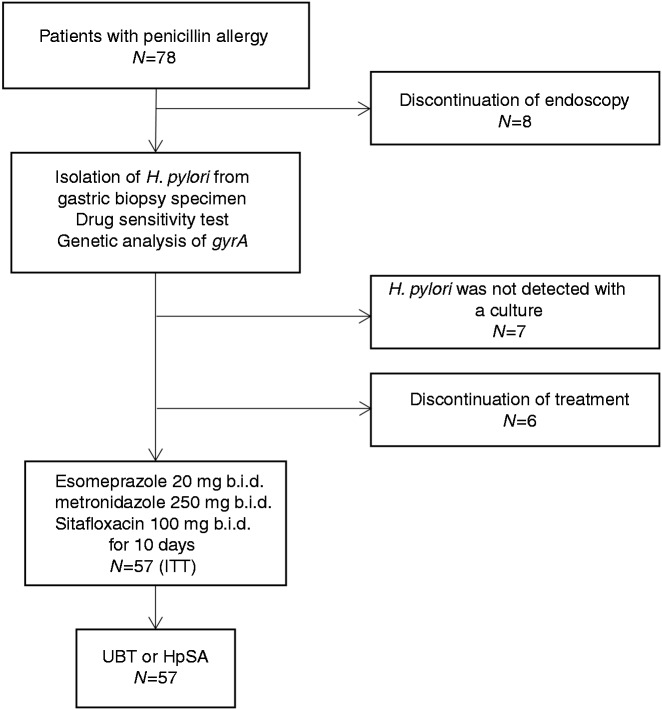

From March 2014 to November 2015, 78 patients were enrolled in this study. Of these, 14 were excluded before dosing owing to refusal of endoscopy (N = 8), or treatment (N = 6). H. pylori was not detected using the culture method in seven patients; hence, these patients were also excluded. Therefore, 57 patients (23 men and 34 women, mean age 57.8 ± 13.7 years) received 10 days of triple therapy (ITT population) (Figure 1). The patient demographics are shown in Table 1. Thirty-three patients were eradication naïve, 19 patients had previously failed one eradication treatment, and five patients had previously failed two eradication treatments. Nine patients had previously received treatment containing MTZ, while five patients had previously received fluoroquinolones. Among these five fluoroquinolone-administered patients, four had received a regimen including LVFX, and one had received a regimen including STFX. Thirty-one patients were infected with gyrA mutation-positive H. pylori strains. Twenty-six, 44, and 12 patients were infected with STFX, CLR, and MTZ-resistant strains, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of this study.

ITT: intention to treat population; UBT: urea breath test; HpSA: Helicobacter pylori stool antigen test.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| n = 57 | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years (mean ± SD)) | 57.8 ± 13.7 |

| Gender male/female, n | 23/34 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 3 (5.3) |

| Alcohol drinkers, n (%) | 21 (36.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2 (mean ± SD)) | 22.5 ± 3.0 |

| Previous H. pylori eradication treatment, n (%) | |

| None | 33 (57.9) |

| Once | 19 (33.3) |

| Twice | 5 (8.8) |

| Previous treatments | |

| AMX, CLR and PPI | 14 (24.6) |

| CLR, MTZ and PPI | 7 (12.3) |

| AMX, MTZ and PPI | 3 (5.3) |

| LVFX and PPI | 3 (5.3) |

| LVFX, MTZ and PPI | 1 (1.8) |

| STFX, MTZ and PPI | 1 (1.8) |

| Dyspepsia, n (%) | 10 (17.5) |

| Peptic ulcer, n (%) | 9 (15.8) |

| H. pylori status | |

| Presence of mutation in gyrA, n (%) | 31 (54.4) |

| Presence of gyrA mutation at D91 only | 11 (19.3) |

| N87 only | 18 (31.6) |

| both D91 and N87 | 2 (3.5) |

| MICs of STFX (µg/ml (mean ± SD)) | 0.26 ± 0.62 |

| MICs of CLR (µg/ml (mean ± SD)) | 29.00 ± 28.07 |

| MICs of MTZ (µg/ml (mean ± SD)) | 6.66 ± 11.53 |

| Resistant to STFX, n (%) | 26 (45.6) |

| Resistant to CLR, n (%) | 44 (77.2) |

| Resistant to MTZ, n (%) | 12 (21.1) |

Alcohol drinkers were defined as people who consumed at least one drink of alcohol per week.

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; AMX: amoxicillin; CLR: clarithromycin; MTZ: metronidazole; LVFX: levofloxacin; STFX: sitafloxacin.

Isolates were defined as resistant to sitafloxacin, clarithromycin and metronidazole, when the MICs were ≥0.12, ≥1 and ≥8 µg/ml, respectively.

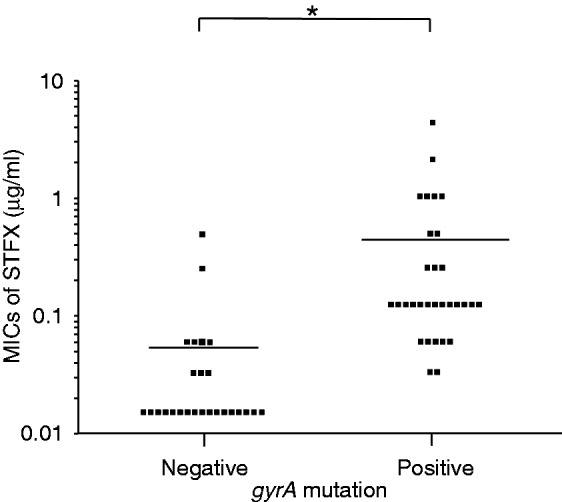

Correlation between gyrA mutation status and MICs of STFX

A dot plot shows a significant association between gyrA mutation status and the MICs of STFX (p = 0.01; Figure 2). The mean MIC of the gyrA-negative strains was 0.04 µg/ml (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.00–0.09 µg/ml), and that of the gyrA-positive strains 0.44 µg/mL (95% CI, 0.15–0.73 µg/ml). In the gyrA-negative strains, 92.3% (24/26) of strains were STFX susceptible. On the contrary, 77.4% (24/31) of strains were STFX resistant in the gyrA-positive strains.

Figure 2.

Correlation between gyrA mutation status and MICs of STFX.

A dot plot shows a significant association between gyrA mutation status and the MICs of STFX (p = 0.01 (Student’s unpaired t test)).

*p < 0.05; MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; STFX, sitafloxacin.

Eradication rates and baseline factors associated with eradication success

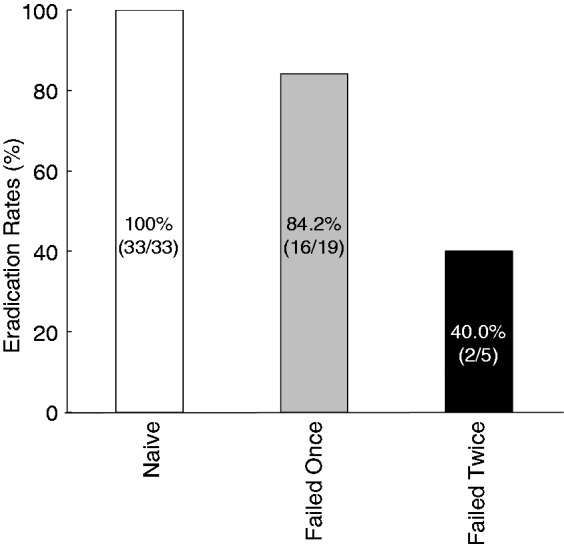

All 57 patients completed the esomeprazole, STFX, and MTZ triple regimen, and the overall eradication rate was 89.5% (51/57) (95% CI: 81.3–97.7%). Associated factors for eradication success are shown in Table 2. All therapy-naïve patients achieved successful eradication of the H. pylori, while the eradication rate in patients who had previously received eradication treatment was 75.0% (18/24) (p < 0.01). Among this group, the eradication rate in patients who had previously failed one regimen was 84.2% (16/19), while in those who had failed two, it was 40.0% (2/5) (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Associated factors for eradication success.

| Eradicated (n = 51) | Not-eradicated (n = 6) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous H. pylori eradication treatment | |||

| No | 33 (64.7) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Yes (once or more) | 18 (35.3) | 6 (100) | |

| Once | 16 (31.4) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Twice | 2 (3.9) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Previous treatment including MTZ | |||

| No | 47 (92.2) | 1 (16.7) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 4 (7.8) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Previous treatment including fluoroquinolones | |||

| No | 47 (92.2) | 5 (83.3) | 0.44 |

| Yes | 4 (7.8) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Use of LVFX | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Use of STFX | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | |

| MTZ resistance (phenotypic) | |||

| Susceptible | 42 (82.4) | 3 (50.0) | 0.10 |

| Resistant | 9 (17.6) | 3 (50.0) | |

| STFX resistance (phenotypic) | |||

| Susceptible | 29 (56.9) | 2 (33.3) | 0.40 |

| Resistant | 22 (43.1) | 4 (66.7) | |

| gyrA mutation (genotypic) | |||

| No | 25 (49.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0.21 |

| Yes | 26 (51.0) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Presence of gyrA mutation at D91 | 11 (21.6) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Presence of gyrA mutation at N87 | 17 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | |

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; MTZ: metronidazole; LVFX: levofloxacin; STFX: sitafloxacin.

Fisher’s exact test was performed to evaluate the associated factors for the eradication success.

Figure 3.

Eradication rates evaluated with the previous treatments.

All eradication-naive patients achieved successful eradication. Among the patients who received previous treatment, the eradication rate of patients who failed once was 84.2% (16/19) and the eradication rate of patients who failed twice was 40.0% (2/5).

The eradication rate in the patients who had previously received MTZ-containing treatment was significantly lower than in those patients who had not received this drug (44.4% (4/9) vs. 97.9% (47/48), p < 0.01). On the contrary, there was no significant correlation between previous treatment containing fluoroquinolones, and eradication failure (80.0% (4/5) vs. 90.4% (47/52), p = 0.44). All four patients treated previously with LVFX-containing regimens experienced successful eradication of H. pylori, whereas one patient treated previously with an STFX-containing regimen did not.

The eradication rates of MTZ-resistant and MTZ-susceptible strains were 75.0% (9/12) and 93.3% (42/45), respectively (p = 0.10). Furthermore, the eradication rates of STFX-susceptible and STFX-resistant strains were 84.6% (22/26) and 93.5% (29/31), respectively (p = 0.40). Most of the patients infected with gyrA mutation-negative strains achieved successful eradication of the H. pylori (96.2%, (25/26)). On the contrary, the eradication rate in patients with gyrA mutation-positive strains was 83.9% (26/31).

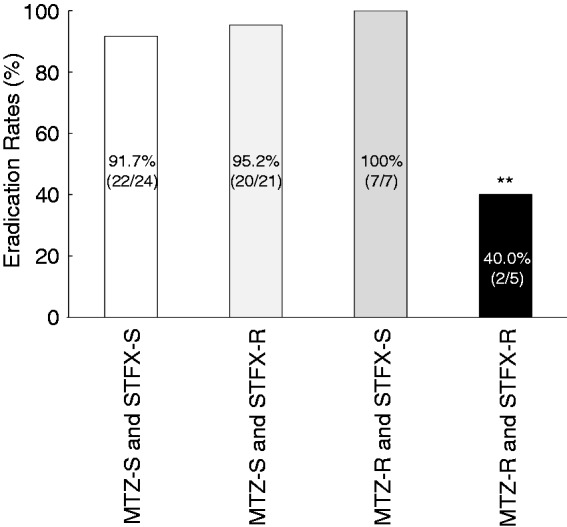

All patients were classified into four groups, based on the combination of H. pylori MTZ- and STFX-resistance (MTZ-S and STFX-S, MTZ-S and STFX-R, MTZ-R and STFX-S, MTZ-R and STFX-R) (Table 3). There was no significant relationship between MTZ- and STFX-resistance (p = 1.00). The eradication rate of H. pylori in each group was 91.7% (22/24), 95.2% (20/21), 100% (7/7), and 40.0% (2/5), respectively (Figure 4). The Chi-square test revealed that there was a significant difference between these four groups (p < 0.01). Residual analysis showed that the eradication rate of the MTZ-R and STFX-R strains was significantly lower than that of the single-resistant or non-resistant strains (p < 0.01). Incidentally, there was no confounding in the distribution between these four groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistances to sitafloxacin and metronidazole.

| STFX-S | STFX-R | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTZ-S | 24 | 21 | 1.00 |

| MTZ-R | 7 | 5 |

STFX: sitafloxacin; MTZ: metronidazole; S: susceptible; R: resistant.

Isolates were defined as resistant to sitafloxacin and metronidazole, when the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were ≥0.12 and ≥8 µg/ml, respectively.

Figure 4.

Eradication rates evaluated with antibiotic resistance.

STFX: sitafloxacin; MTZ: metronidazole; S: susceptible; r: resistant.

Resistance to STFX or MTZ was defined as minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ≥ 0.12 or ≥8 µg/ml, respectively.

The eradication rates of each group (MTZ-S and STFX-S, MTZ-S and STFX-R, MTZ-R and STFX-S, MTZ-R and STFX-R) were 91.7% (22/24), 95.2% (20/21), 100% (7/7) and 40.0% (2/5), respectively. Chi-square test revealed there was significant difference among these four groups (p < 0.01); moreover, residual analysis showed the eradication rate of the MTZ-R and STFX-R strains was significantly lower among the group (**p < 0.01).

The eradication rates of wild-type gyrA, mutation in N87 only, D91 only and double gyrA mutation were 96.2% (25/26), 83.3% (15/18), 81.8% (9/11) and 100% (2/2), respectively. The eradication rates were not different by the position of gyrA mutation (p = 1.00). All of the strains treated with fluoroquinolones-containing regimens previously had mutation in the gyrA gene. Among four strains previously treated with LVFX-containing regimens, two strains had a mutation at N87, one strain had a mutation at D91 and one strain had a mutation at both N87 and D91. One strain treated with STFX-containing regimens previously had a mutation at N87.

Safety assessment

All patients in the ITT population completed the entire treatment regimen, although adverse events were reported in 31.6% (Table 4). The most common adverse events were soft stool, diarrhea, dysgeusia, and stomatitis, though these were mild and tolerable in severity; no severe adverse events were reported. After treatment was discontinued, all of the patients recovered fully from their symptoms.

Table 4.

Adverse events.

| n = 57 | |

|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 18 (31.6%) |

| Soft stool, n (%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Dysgeusia, n (%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Stomatitis, n (%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Itching, n (%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Skin rash, n (%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Headache, n (%) | 1 (1.8%) |

Discussion

The present study showed a significant association between antibiotic resistance, and the efficacy of a 10-day course of STFX and MTZ-containing triple therapy, in patients with penicillin allergy. The eradication rate of the MTZ-R and STFX-R strains (40.0% (2/5)) was lower than that reported for the other single-resistant and double-sensitive groups. Interestingly, the patients infected with MTZ-S and STFX-R strains, and MTZ-R and STFX-S strains, achieved almost complete eradication (95.2% (20/21) and 100% (7/7)), respectively. These data revealed that 10 days of STFX and MTZ triple therapy is highly effective if the strain is susceptible to either STFX or MTZ. However, this regimen might be insufficient for MTZ-R and STFX-R strains.

Most of the patients infected with gyrA non-mutated strains achieved successful eradication (96.2%, (25/26)). We reported previously that 10 days of MTZ and STFX triple therapy (third-line) achieved complete eradication of gyrA mutation-negative strains.10 It was revealed in this study, however, that 10 days of MTZ and STFX triple therapy is almost completely effective against gyrA mutation-negative strains in penicillin-allergic patients, as well as those who have failed second-line therapy.

Concerning gyrA mutation-positive strains, 83.9% (26/31) of patients achieved successful eradication of H. pylori in this study. In contrast, we reported previously that the eradication rate of gyrA mutation-positive strains treated with the same regimen was 66.7%.10 We hypothesize that the difference between these eradication rates is due to the variance in MTZ-resistance, because the patients who received this third-line therapy had previously failed MTZ-containing therapy at least once in our previous study.10 The prevalence of MTZ-resistant H. pylori has been reported to range from 8% to 80% in different countries.19 In Japan, it has been reported to be only 10%–15%, which is the lowest rate in the world. In contrast, the prevalence is much higher especially in developing countries, where it is usually more than 60%. Therefore, the efficacy of 10 days of STFX and MTZ triple therapy might decrease in the high prevalent areas of MTX-resistant H. pylori.

Previous treatment with MTZ was a significant predictor of eradication failure; conversely, previous treatment with fluoroquinolones was not correlated with this outcome. Among the fluoroquinolone-exposed group, all four patients previously treated with LVFX-containing regimens achieved successful H. pylori eradication with 10 days of STFX and MTZ triple therapy (Table 2). This result may be attributable to the choice of fluoroquinolone; Liou et al. reported that the eradication rates of gyrA-positive and -negative H. pylori strains using an LVFX-based regimen were 41.7% (5/12) and 82.7% (110/133), respectively.20 In contrast, Murakami et al. showed that an STFX-based regimen was more effective than an LVFX-based regimen as a third-line therapy (70.0% vs. 43.1%, p < 0.001).21 We have also reported that 10 days of the STFX and MTZ-containing triple therapy achieved an eradication rate of 76.4% (42/55) in a third-line setting.10 Finally, STFX-containing regimens have recently been established as rescue therapies.10,13,21–23 These previous data, and the present study, have therefore demonstrated that STFX could be a promising drug for penicillin-free eradication regimens.

Furuta et al. reported that 28 penicillin-allergic patients achieved successful H. pylori eradication with seven or 14 days of an STFX and MTZ-containing triple regimen.24 Among the H. pylori strains from these patients, 15 were evaluated for sensitivity to MTZ; however, unfortunately the strains were not analyzed for susceptibility to STFX. Thirteen percent (2/15) of the strains were resistant to MTZ, although they were eradicated with seven days of an STFX and MTZ-containing triple regimen. This outcome is consistent with our results for the MTZ-R and STFX-S group.

In this study, we revealed that the best predictor of eradication failure, when using 10 days of an STFX and MTZ-containing triple regimen in penicillin-allergic patients, is double-antibiotic resistance to MTZ and STFX. Therefore, we should consider substituting either MTZ or STFX in order to eradicate double-resistance strains. A low rate of resistance to rifabutin has been already reported.25 Furthermore, we have previously shown that rifabutin-containing treatments were highly effective as third- or fourth-line therapy.18 Thus, rifabutin might be a suitable alternative antibiotic for the eradication of MTZ-R and STFX-R H. pylori strains in penicillin-allergic patients.

The generalizability of the eradication rate in this study is uncertain, since it is a single-center study. We previously reported that the eradication rates of first-line seven days of amoxicillin (AMX), clarithromycin and PPI triple therapy and second-line seven days of AMX, MTZ and PPI triple therapy were 66.5% and 91.8% in the Tokyo metropolitan hospitals including our institution, respectively.26,27 As far as the results of our institution were concerned, the eradication of first-line and second-line treatments were 67.8% and 90.0%, respectively (unpublished data). Considering these results, enrolled patients in this study were suggested to not be a biased population.

In conclusion, the 10-day course of MTZ and STFX triple therapy was safe and highly effective for the eradication of H. pylori in penicillin-allergic patients. Double resistance to MTZ and STFX was an important predicting factor for eradication failure in this context. However, a 10-day course of this regimen was highly effective if the strain exhibited resistance to either STFX or MTZ only.

Declaration of conflicting interests

During the last two years, H.S. received scholarship funds for the research from Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Toshiba, Co., and Tsumura Co. Ltd. and received service honoraria from Astellas Pharm Inc, Astra-Zeneca K.K., Daiichi-Sankyo Co. Ltd., Mylan EPD G.K., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Zeria Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. T.K. received scholarship funds for the research from Astellas Pharm Inc, Astra-Zeneca K.K., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Eisai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. JIMRO Co. Ltd., Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and received service honoraria from Astellas Pharm Inc, Eisai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., JIMRO Co. Ltd., Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Miyarisan Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Zeria Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (grant number 26860527, to J.M.), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research B (grant number 16H05291, to H.S.) Scientific Research C (grant number 25460301, to T.M.), and a Grant-in-Aid for challenging Exploratory Research (grant number 26670065, to H.S.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (grant number S1411003, to H.S.), the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research grants (to H.S.), a grant from the Smoking Research Foundation (to H.S.), a grant from Takeda Science Foundation (to J.M.) and Keio Gijuku Academic Development Funds (to J.M. and to H.S.).

References

- 1.Sasaki M, Ogasawara N, Utsumi K, et al. Changes in 12-year first-line eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori based on triple therapy with proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin and clarithromycin. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2010; 47: 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macy E, Poon K-YT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: Age and sex effects. Am J Med 2009; 122: 778.e1–778.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albin S, Agarwal S. Prevalence and characteristics of reported penicillin allergy in an urban outpatient adult population. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014; 35: 489–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gisbert JP, Barrio J, Modolell I, et al. Helicobacter pylori first-line and rescue treatments in the presence of penicillin allergy. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60: 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gisbert JP, Pérez-Aisa A, Castro-Fernández M, et al. Helicobacter pylori first-line treatment and rescue option containing levofloxacin in patients allergic to penicillin. Dig Liver Dis 2010; 42: 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, Gisbert JL, Marcos S, et al. Helicobacter pylori first-line treatment and rescue options in patients allergic to penicillin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22: 1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Torres M, Salgado-Mercado R, Ríos-Bedoya CF, et al. High eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori infection with first- and second-line combination of esomeprazole, tetracycline, and metronidazole in patients allergic to penicillin. Dig Dis Sci 2005; 50: 634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017; 66: 6–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones N, Chiba N, Fallone C, et al. Helicobacter pylori in First Nations and recent immigrant populations in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol 2012; 26: 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori H, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, et al. Efficacy of 10-day sitafloxacin-containing third-line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori strains containing the gyrA mutation. Helicobacter 2016; 21: 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaira D, Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, et al. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection with a new non-invasive antigen-based assay. HpSA European study group. Lancet 1999; 354: 30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Kurabayashi K, et al. Gatifloxacin resistance and mutations in gyra after unsuccessful Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50: 1538–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzaki J, Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, et al. Efficacy of sitafloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori after failures of first- and second-line therapies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 1643–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato M, Asaka M, Ohara S, et al. Clinical studies of 13C-urea breath test in Japan. J Gastroenterol 1998; 33 (Suppl) 10: 36–39. [PubMed]

- 15.Ge Z, Taylor DE. H. pylori DNA transformation by natural competence and electroporation. Methods Mol Med 1997; 8: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuzaki J, Suzuki H, Tsugawa H, et al. Homology model of the DNA gyrase enzyme of Helicobacter pylori, a target of quinolone-based eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25(Suppl 1): S7–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimura S, Kato S, Iinuma K, et al. In vitro activity of fluoroquinolone and the gyrA gene mutation in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children. J Med Microbiol 2004; 53(Pt 10): 1019–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori H, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, et al. Rifabutin-based 10-day and 14-day triple therapy as a third-line and fourth-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A pilot study. United European Gastroenterol J 2016; 4: 380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, Hibi T. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Future Microbiol 2010; 5: 639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liou JM, Chang CY, Sheng WH, et al. Genotypic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains correlates with susceptibility test and treatment outcomes after levofloxacin- and clarithromycin-based therapies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami K, Furuta T, Ando T, et al. Multi-center randomized controlled study to establish the standard third-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 1128–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furuta T, Sugimoto M, Kodaira C, et al. Sitafloxacin-based third-line rescue regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29: 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugimoto M, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, et al. Four-times-daily dosing of rabeprazole with sitafloxacin, high-dose amoxicillin, or both for metronidazole-resistant infection with Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Helicobacter. Epub ahead of print 23 May 2016. DOI: 10.111/hel.12319. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Furuta T, Sugimoto M, Yamade M, et al. Eradication of H. pylori infection in patients allergic to penicillin using triple therapy with a PPI, metronidazole and sitafloxacin. Intern Med 2014; 53: 571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, et al. Helicobacter pylori resistance to rifabutin in the last 7 years. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 5374–5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asaoka D, Nagahara A, Matsuhisa T, et al. Trends of second-line eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori in Japan: A multicenter study in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Helicobacter 2013; 18: 468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai T, Takahashi S, Suzuki H, et al. Changes in the first line Helicobacter pylori eradication rates using the triple therapy—a multicenter study in the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo Helicobacter pylori study group). J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29(Suppl 4): 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]