Abstract

This study is to analyze the prevalence and the associated lifestyle risk factors of self-reported allergic rhinitis (AR) in Kazakh population of Fukang City.

A cross-sectional study was conducted using stratified random sampling method and 1689 Kazak people were surveyed. A standard questionnaire was used for face-to-face interview.

The prevalence of self-reported AR of Kazakh population in Fukang City was 13.7%, and sneezing was the most common symptoms (54.6%) with no significant differences among age, sex, and weight. The incidence of asthma in Kazakh people was correlated with age, and the incidence of allergies in Kazakh people was correlated with weight. Skin pruritus was the most common symptom for allergy (42.7%). The AR incidence was correlated with sinusitis and asthma, and was mostly associated with carpet use. For diet, the AR incidence was positively correlated with meat and fruit, and negatively correlated with beans and milk.

The prevalence of AR is high among Kazakh people in Fukang City, and its incidence is closely related with lifestyle risk factors such as carpet use and meat and fruit consumption.

Keywords: allergic rhinitis, epidemiology study, Kazak

1. Introduction

From the perspective of allergy, allergic rhinitis (AR) is a noninfectious nasal mucosa inflammation that is mediated by immunoglobulin (Ig) E.[1] AR is the specific inflammation against allergen by immune defense cells on nasal mucosa, which can lead to chronic nasal symptoms such as sneezing, itching, runny nose, and nasal congestion.[2] For patients with intermittent episodes, the symptoms are generally mild with short duration, and can be controlled by local and/or systemic medications with less effect on quality of life.[3] For patients with consistent attack, the life quality is generally low and long-term medications are required. However, due to the poor drug efficacy, immune suppression therapy is generally needed.[4]

The AR prevalence in Urumqi was high, and ranked the first among 11 cities surveyed across China.[5] So far, there is no effective intervention to decrease the high prevalence. In a longitudinal study on the relationship between AR/ non-AR and asthma in Western Europe involving more than 6000 subjects, it showed that AR and non-AR were both risk factors for asthma.[6] Epidemiology studies have showed that patients usually have asthma and rhinitis in the meantime and about one-third of AR patients would concurrently have asthma.[7–9] AR and asthma share the similar family characteristics and familial risk.[10] Therefore, information on the AR population prevalence and AR lifestyle risk factors is essential for the early diagnosis and intervention of AR.

In this study, a cross-sectional study of the prevalence of self-reported AR and the associated lifestyle risk factors was performed in Kazakh population of Fukang City, Xinjiang, China.

2. Methods

2.1. Subject selection and sampling

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using multistage stratified cluster sampling method. Two towns were randomly selected in Fukang City, and 2 streets were randomly selected in each town. Then, 2 communities were randomly selected on each pre-selected street. Of the 8 selected communities, 65 households were selected, and all surveyed households have resided in the area for more than 2 years. Prior written and informed consent were obtained from every subject and the study was approved by the ethics review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University.

2.2. Household data collection

All investigators received standard training before the survey. The questionnaire was developed on the basis of Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN).[11] The surveyed factors mainly included symptoms and lifestyle factors of AR, asthma, and other allergies. The diagnosis of AR was in accordance with previous national epidemiology surveys 2010 Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) standard.[12] All individuals were interviewed personally, or by the family if the individual was absent from home and the family signed for representation.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Quantitative data were analyzed by Chi-square test. The odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) was calculated. P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics

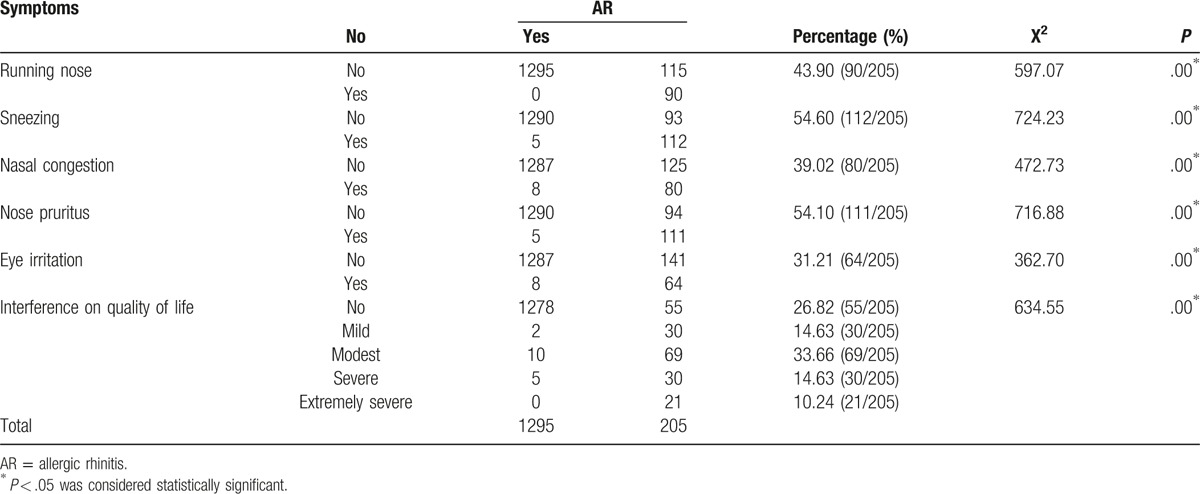

There were 1689 people identified and 1500 questionnaires were qualified. Of them, 205 people were diagnosed of AR, and the AR prevalence was 13.7%. The effect of AR on life quality of Kazakh AR patients was moderate. Among typical AR symptoms, sneezing had the highest incidence (54.60%), followed by nose pruritus (54.10%), runny nose (43.90%), nasal congestion (39.02%), and eye irritation (31.21%) (Table 1). There were no significant differences in age and gender among Kazakh AR patients, and there was no difference in weight and height for AR susceptibility. It indicated that there were no differences in population general characteristics between AR patients and healthy controls.

Table 1.

Baseline information of Kazakh people.

3.2. AR symptoms

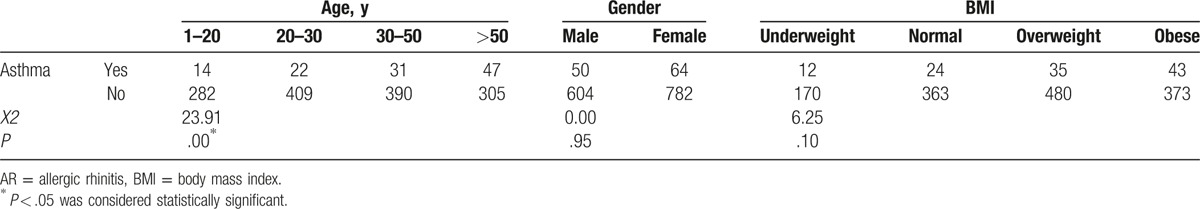

To determine the comorbidity of AR and asthma, the incidence of AR with asthma was examined. It showed that the incidence of AR with asthma increased with age (Table 2). The lower airway symptoms presented as paroxysmal chest tightness and cough (39.5–43.8%), followed by suffocation (21%) and wheezing (8.8%). The majority onset of asthma was associated with flu (40%) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics and analysis of Kazakh people with asthma.

Table 3.

Characteristics and analysis of Kazakh people with lower airway symptoms.

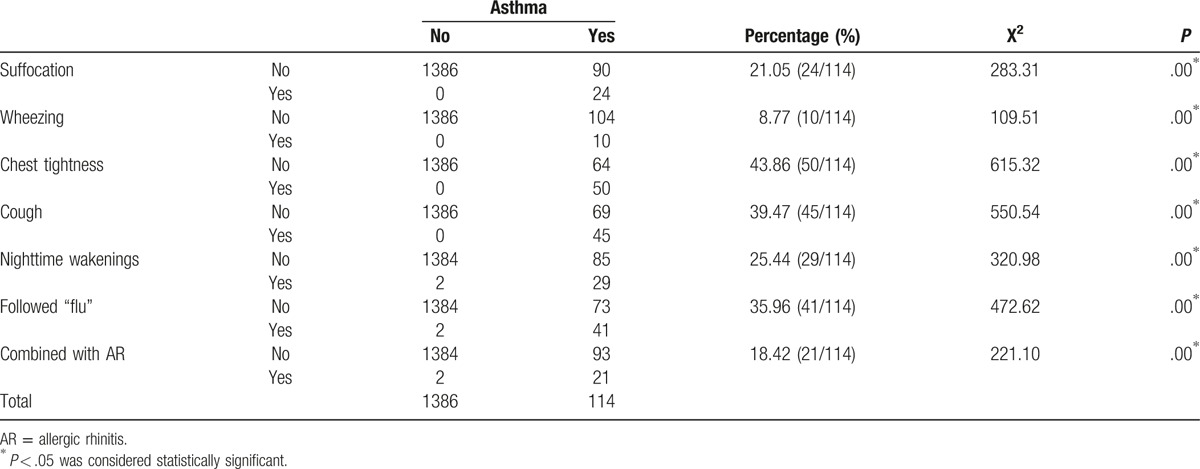

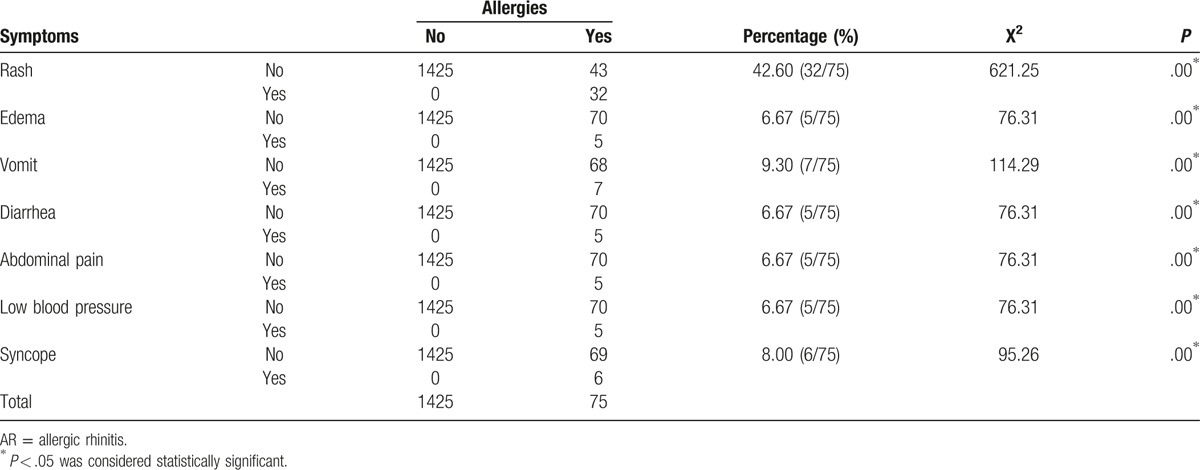

In addition, there were significant differences in weight for AR patients with other allergies, who were disproportionally overweight or obese. For other allergies, skin pruritus was the most common (42.7%), followed by edema and allergy shock (6.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics and analysis of Kazakh people with allergies.

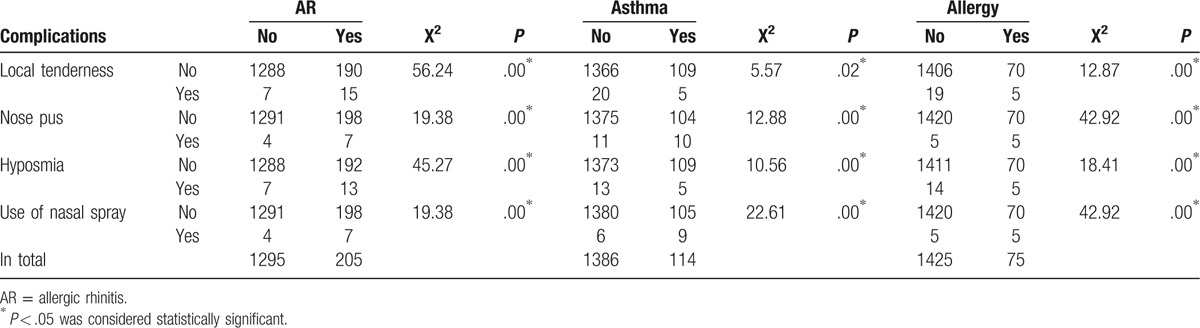

3.3. AR complications

The AR complications were analyzed. As summarized in Table 5, the majority of AR patients were complicated with local tenderness and hyposmia with statistical significance (P = .00 < .05). For AR patients with asthma, the main complication was nose pus and use of nasal spray with statistically significance (P < .05). However, there was no significant difference among AR patients with other allergies.

Table 5.

The AR complications among AR Kazakh people.

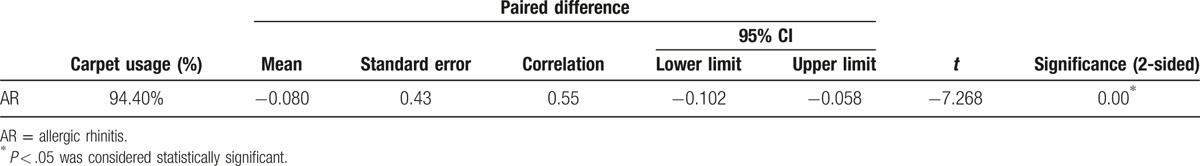

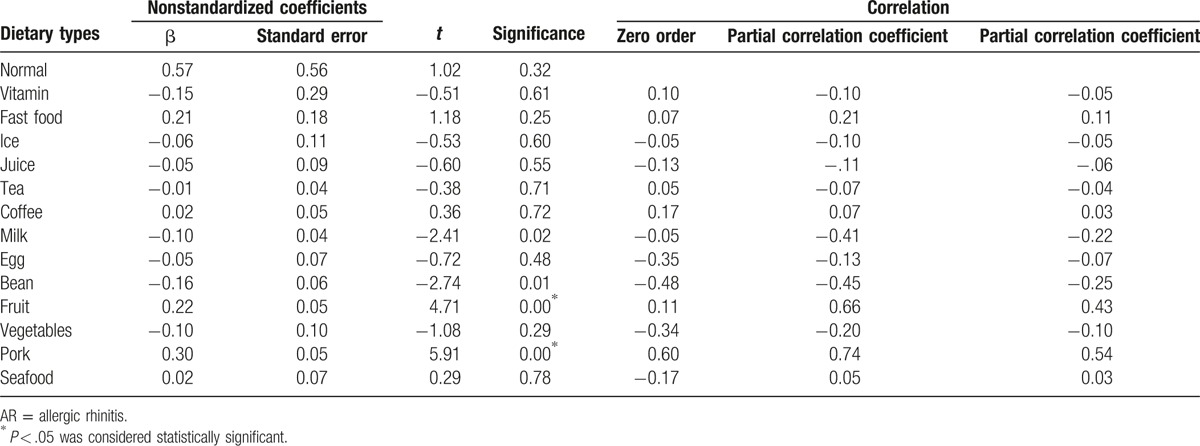

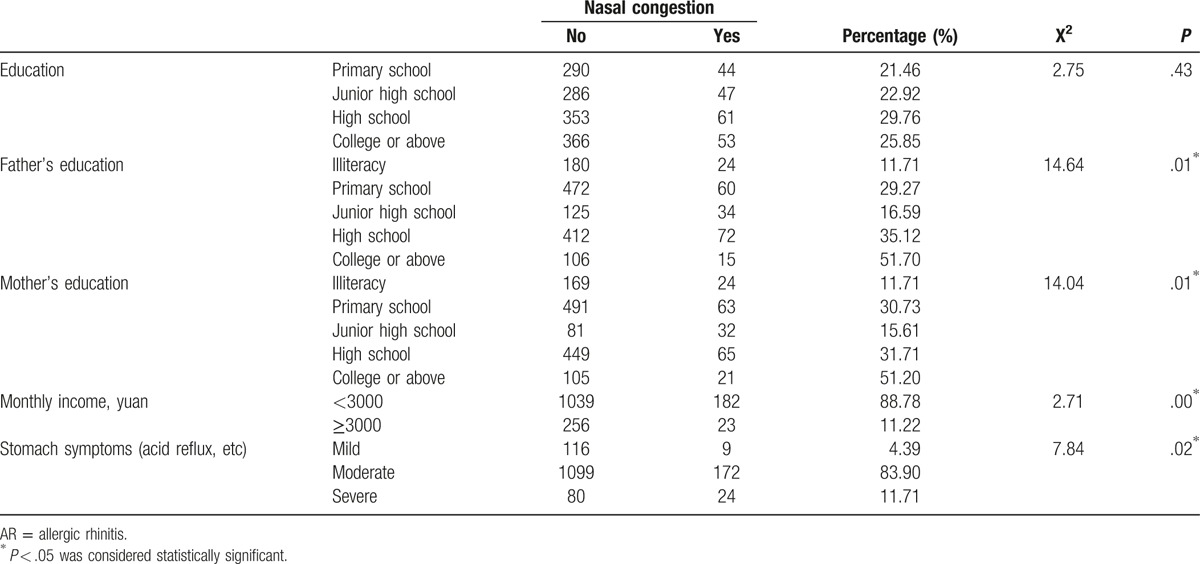

3.4. Lifestyle factors

To determine the lifestyle factors contributing to AR among Kazakhs, information on their lifestyle factors was collected. By analyzing lifestyle factors and dietary habits, it is found that 94.4% of Kazakh AR patients used carpet, and carpet use was correlated with the incidence of AR (Table 6). Carpet may contain a large number of mites, mold, and dust, which are common allergens implicated with AR, especially the perennial AR.[13] In addition, it is found that the consumption of meat, fruit, milk, and beans was also correlated with AR. Intake of meat (0.739) and fruits (0.658) was positively correlated with AR, while milk (−0.408) and beans (−0.453) were negatively correlated with AR (Table 7). Moreover, as summarized in Table 8, more than 90% of the Kazakh had stomach symptoms, which included all AR patients. About 88.9% of the Kazak AR patients earned a monthly income of less than 3000 Yuan on average. The education levels of AR patients’ parents were lower than non-AR patients’ parents, while most AR patients were of high school and college degree. Due to religious reasons, the smoking rate was low for Kazakh people, and no association was found between smoking and allergic airway inflammation.

Table 6.

Correlation of carpet use with AR for Kazakhs.

Table 7.

Correlation of dietary habits and AR for Kazakhs.

Table 8.

Education, income, and stomach symptoms among AR Kazakh people.

4. Discussion

AR is a common clinical illness and a global challenge. AR is an IgE-mediated nasal inflammatory disease that is triggered by contact of allergen[14,15] and is featured as eosinophilic inflammation.[16] However, many clinical issues of AR remained unresolved, such as the immunological detection for AR diagnosis[17,18] and limited use of evidence-based treatment guidelines.[19–21]

There are epidemiology studies on AR prevalence in major cities across China[5]; however, they were conducted by telephone. Hence, this information had limited accuracy, and face-to-face interview is needed, especially for lifestyle information. In this study, Kazakhs were surveyed, whose population size was only second to the Uighur among minorities in Xinjiang, and it was found in baseline survey that Kazakhs were more susceptible to airway allergic diseases. In addition, epidemiology information on Kazakhs was seldomly collected and reported; thus, AR information gathered from this study would greatly benefit future AR epidemiology study and AR prevention.

There are many differences in lifestyle, dietary, and genetic factors between minority groups and Hans. Much effort has been made on the differences of AR gene susceptibility between Han and minority groups.[22,23] Clinically, it is found that Kazakh people are more prone to upper respiratory tract allergies than other ethnic groups; however, no scientific research has been conducted to provide the actual statistics. This study is the first to provide baseline of AR-related information of Kazakh population, including the disease, economic burden, and the relationship between lifestyle and AR pathogenesis.

The study is limited in the language barrier between Kazakhs and Han, the small population size of Kazakh, and the lack of nasal inspection. However, Kazakh clinicians were included in the design to overcome the language barrier, and the study used carefully designed sampling to minimize the selection bias. In the future, studies are needed with larger sample size and better study design to further examine the pathogenesis of AR for minorities in China.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members from Department of Allergy and Department of Ear, Nose and Throat in the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University for their help in data collection. We also thank Dr. Yong Sun (from Department of Preventative Care, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University) and Cheng Li (from Department of Information, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University) for their valuable help. We thank all community staff from Fukang City for their support to this study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AR = allergic rhinitis, ARIA = allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma, CI = confidence interval, Ig = immunoglobulin, OR = odds ratio.

Funding/support: This work was supported by China National Natural Science Foundation (No. 81160125 and No. 81570896).

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Salo PM, Calatroni A, Gergen PJ, et al. Allergy-related outcomes in relation to serum IgE: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:1226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anolik R. Mometasone Furoate Nasal Spray With Loratadine Study Group. Clinical benefits of combination treatment with mometasone furoate nasal spray and loratadine vs monotherapy with mometasone furoate in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100:264–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:S1–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seidman MD, Gurgel RK, Lin SY, et al. Clinical practice guideline: allergic rhinitis executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;152:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Han DM, Zhang L, Huang D, et al. Self-reported prevalence of allergic rhinitis in eleven cities in China. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2007;42:378–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, et al. Rhinitis and onset of asthma: a longitudinal population-based study. Lancet 2008;372:1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bousquet J, Schünemann HJ, Samolinski B, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA): achievements in 10 years and future needs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:1049–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Groot EP, Nijkamp A, Duiverman EJ, et al. Allergic rhinitis is associated with poor asthma control in children with asthma. Thorax 2012;67:582–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Oka A, Matsunaga K, Kamei T, et al. Ongoing allergic rhinitis impairs asthma control by enhancing the lower airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen M, Jiang WJ. Individual status, genetics, environment and childhood asthma: a meta-analysis of case-control studies in recent ten years in China. China Med Pharm 2011;1:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hastan D, Fokkens WJ, Bachert C, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis in Europe: an underestimated disease. A GA2LEN study. Allergy 2011;66:1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Baena-Cagnani CE, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:466–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Karra L, Haworth O, Priluck R, et al. Lipoxin B4 promotes the resolution of allergic inflammation in the upper and lower airways of mice. Mucosal Immunol 2015;8:852–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Subspecialty Group of Rhinology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Subspecialty Group of Rhinology and Pediatrics, Society of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery: Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of pediatric allergic rhinitis (2010, Chongqing). Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2011;46:7–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Togias A. Unique mechanistic features of allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;105:599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gu ZY, Li Y. Allergology in ear nose throat head and neck diseases: People's Health Publishing House. Beijing 2012;36:55–174. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang L, Wei J, Han D. Current state of diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis in China. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2010;45:420–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ryu JH, Yoo JY, Kim MJ, et al. Distinct TLR-mediated pathways regulate house dust mite–induced allergic disease in the upper and lower airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:549–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Subspecialty Group of Rhinology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Subspecialty Group of Rhinology, Society of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery: Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis (2009, Wuyishan). Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2009;44:977–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nathan RA, Eccles R, Howarth PH, et al. Objective monitoring of nasal patency and nasal physiology in rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:S442–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rochat MK, Illi S, Ege MJ, et al. Allergic rhinitis as a predictor for wheezing onset in school-aged children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;26:170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cui Z, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. Analysis of HLA-DQB1 polymorphism for patienets with allergic rhinitis of Uygur and Han people in Xinjiang. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 2011;25:645–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen QY, Yang YP, Xiang YB, et al. Relationship between TAP1 ∗rs2071480 gene polymorphisms and allergic rhinitis in the Chinese Han population in Xinjiang. J Med Postgrad 2012;25:805–9. [Google Scholar]