ABSTRACT

The cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel (gene: SCN5A, protein: NaV1.5) is responsible for the sodium current that initiates the cardiomyocyte action potential. Research into the mechanisms of SCN5A gene expression has gained momentum over the last few years. We have recently described the transcriptional regulation of SCN5A by GATA4 transcription factor. In this addendum to our study, we report our observations that 1) the linker between domains I and II (LDI-DII) of NaV1.5 contains a nuclear localization signal (residues 474–481) that is necessary to localize LDI-DII into the nucleus, and 2) nuclear LDI-DII activates the SCN5A promoter in gene reporter assays using cardiac-like H9c2 cells. Given that voltage-gated sodium channels are known targets of proteases such as calpain, we speculate that NaV1.5 degradation is signaled to the cell transcriptional machinery via nuclear localization of LDI-DII and subsequent stimulation of the SCN5A promoter.

KEYWORDS: gene expression, mutagenesis, nuclear localization signal, transcription factor, voltage-gated sodium channel

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium channels are vital proteins in cardiac physiology. Upon changes in membrane potential, sodium channels open and enable the inward, depolarising sodium currents that underlie Phase 0 of the cardiomyocyte action potential.1 NaV1.5, encoded by the SCN5A gene, is the pore-forming, α subunit, of the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel, and is necessary and sufficient to generate voltage-dependent, inward sodium currents. NaV1.5 is an essential protein and Scn5A −/− mice are not viable, while Scn5A +/− knockout mice display cardiac conduction defects and ventricular tachycardia.2

In humans, genetic variants in SCN5A have been linked to cardiac arrhythmias (atrial and ventricular fibrillation), sudden cardiac death syndromes (Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, sudden infant death syndrome) and other cardiac phenotypes (conduction defects, sick sinus syndrome).3 We have recently shown that SCN5A expression is regulated by the GATA4 transcription factor in the human heart.4 Recent evidence suggests that abnormal SCN5A gene expression is associated with arrhythmogenic diseases (discussed in Tarradas et al. 2017),4 and therefore the understanding of how SCN5A expression is controlled constitutes an important step forward in the field of cardiac diseases related to NaV1.5 dysfunction.

NaV1.5 is a large (2016 residues, ca. 220 KDa), hydrophobic, integral membrane protein that consists of 4 homologous domains (termed DI to DIV), joined by cytosolic interdomain linkers.1 Great efforts over the past 7 y have shed light onto the structure of other voltage-gated sodium channels (mainly bacterial proteins),5,6 and the first structure of an eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel α subunit has recently been solved.7 While these and other studies have provided invaluable insight into voltage-gating mechanisms and pore structure, the role and organization of cytosolic domains is less clear. The linker between domains DI and DII (LDI-DII) of NaV1.5 contains 295 residues and has been of particular interest to us and other groups due to the fact that LDI-DII undergoes post-translational modifications including phosphorylation and arginine methylation (for a recent review see8). Biochemical, genetic and electrophysiological studies suggest that LDI-DII participates in the regulation of channel inactivation.9

Voltage-gated sodium channels have long been known to be regulated by proteases.10 For example, calpain cleaves the brain isoform of the voltage-gated sodium channel, NaV1.2, at LDI-DII.11 Calpain sodium channel fragments interact and localize at the plasma membrane hours after calpain activation,11 suggesting that these fragments retain the protein–protein interactions that hold the sodium channel macromolecular complex together. However, there is currently no information on whether these fragments are subsequently degraded. A thought-provoking alternative is that sodium channel proteolysis creates new proteins with modified biologic activities. In this addendum, we further our understanding of SCN5A gene expression by showing that LDI-DII contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS), localizes to the cell nucleus when expressed as an isolated domain in cardiac-like H9c2 cells, and increases SCN5A promoter activity in vitro.

Results

LDI-DII is predicted to be a target for calpain and contains an NLS

Previous reports have shown that LDI-DII from NaV1.2 is a target for calpain. We used 2 published protease site prediction algorithms to search for possible calpain cleavage sites in the NaV1.5 LDI-DII sequence (residues 416–711).12,13 Both algorithms predicted calpain cleavage after position E462. The other common hot spots for calpain cleavage in LDI-DII were the regions spanning residues 512–524, 573–579, and 630–644 (Fig. 1A).

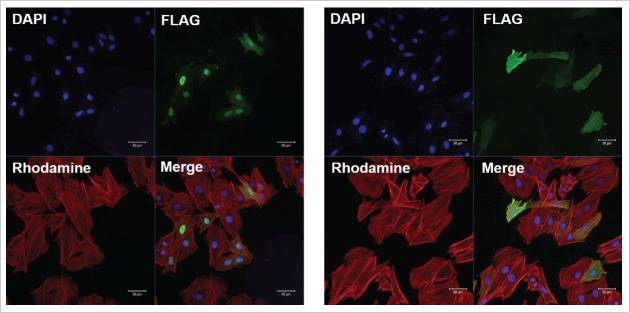

Figure 1.

(A) Sequence of LDI-II (residues 416–711 of NaV1.5) highlighting predicted calpain cleavage sites (E462, and regions 512–524, 573–579, and 630–644) as well as the putative NLS (underlined). (B) Sequence alignment of possible NLS in NaV members (NaV1.5 numbering), highlighting conserved arginines (in black) and R residues 474, 475, 478, 479 and 481 (underlined).

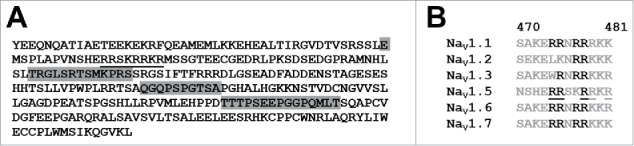

Inspection of the sodium channel LDI-DII sequences revealed the presence of a conserved arginine-rich motif including residues 474–481 (Fig. 1A and B). We hypothesized that this motif could be a classical basic NLS. To test this hypothesis, we cloned the entire NaV1.5 LDI-DII as a FLAG-YFP fusion protein in a mammalian expression vector. We transfected this plasmid into H9c2 cells and observed LDI-DII expression mainly in the nucleus (Fig. 2, left). When we mutated R474, R475, R478, R479 and R481 to K residues, the localization of the linker was no longer restricted to cell nuclei (Fig. 2, right). We repeated these transfections more than 10 times and reproducibly observed a similar fluorescence pattern.

Figure 2.

Representative confocal microscopy images of H9c2 cells transfected with LDI-II including intact (left) and mutated (right) NLS. Scale bar corresponds to 50 µm.

LDI-DII increases the activity of SCN5A promoter

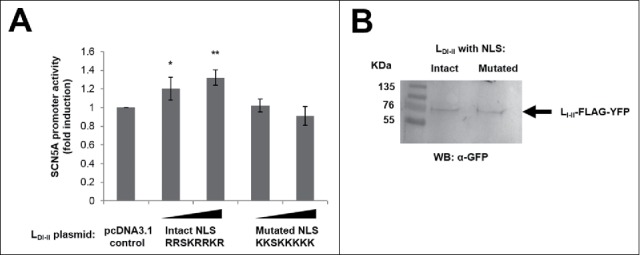

Why would an isolated cytosolic domain of a voltage-gated sodium channel localize to the cell nucleus? We asked whether LDI-DII could modify SCN5A expression. We transfected H9c2 cells with a plasmid expressing luciferase under the control of the SCN5A promoter (“promoter A” in the original publication),4 together with plasmids expressing either LDI-DII with an intact NLS, or LDI-DII with a mutated NLS (R474, R475, R478, R479 and R481 to K as above). Our luciferase assays showed that LDI-DII with intact NLS, but not the mutated version, stimulated SCN5A promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(A) Luciferase experiments in H9c2 cells transfected with an SCN5A promoter-luciferase construct and increasing amounts (447 and 895 ng) of the indicated pcDNA3.1-based LDI-II expression plasmids encoding for LDI-II with intact and mutated NLS (residues 474–481). Luciferase values were normalized to renilla and are shown as fold induction relative to non-overexpressing control conditions (mean ± SEM, n = 4). Significance was examined by the t-test relative to control: * p = 0.03, ** p = 0.001. (B) Representative Western blot showing expression of LDI-II with intact and mutated NLS (895 ng plasmid each).

Discussion

In this addendum, we have built on our recently published investigation of SCN5A transcriptional regulation,4 to identify another possible mechanism controlling SCN5A gene expression i. e. LDI-DII stimulation of the SCN5A proximal promoter. We have identified an NLS in LDI-DII and provided evidence that nuclear LDI-DII enhances SCN5A transcription. These new results should be regarded as preliminary at this stage given the nature of our cell and in vitro studies, but they raise the exciting possibility that SCN5A expression may be regulated by sodium channel proteolysis.

Proteolysis of sodium channel β subunits is known to regulate transcription of α subunits such as NaV1.1, the brain isoform of the voltage-gated sodium channel. The group of Kovacs, and others, demonstrated that 1) ADAM10 and BACE1 proteases cleave off the extracellular domain of the β2 subunit; 2) γ-secretase releases the β2 intracellular domain, and 3) the β2 intracellular domain is internalised into the cell nucleus (by unknown mechanisms) and induces an increase in NaV1.1 mRNA and protein levels.14,15,16 The β1 subunit is also a target for BACE1 in vitro,16 and β1 silencing has recently been shown to result in decreased NaV1.1 mRNA (and protein) levels in cell models.17

NLS often consist of short arginine-rich sequences, and have been described in voltage-gated potassium channels, notably KV10.1.18 We have found that NaV1.5 LDI-DII localizes to the cell nucleus when expressed as an isolated domain in H9c2 cells, and that this nuclear localization is abrogated by mutation of 5 R residues to K in the sequence RRSKRRKR spanning residues 474–481 of NaV1.5. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an NLS in α subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels. Sequence alignment suggests that the NLS could be conserved among other members of the voltage-gated sodium channel family, including conservation of R474 and R475 in 4 and 5 members of the family, respectively, and an essential R478 (NaV1.5 numbering throughout, Fig. 1B). Taking together our new observations with previous reports, it is tempting to speculate that calpain (alone or in combination with other proteases) cleavage of α subunits11,19 creates LDI-DII fragments containing NLS, and that nuclear LDI-DII play a role in cardiac sodium channel transcriptional regulation, likely in combination with transcription factors.

Our approach was limited by the lack of information on precise calpain proteolytic site(s) within LDI-DII. Both algorithms used here predicted cleavage after E462, and we identified 3 possible calpain sites C-terminal to the NLS. Given these uncertainties, we decided to clone the complete 295-residue long LDI-DII domain and not smaller LDI-DII fragments. Mapping both calpain sites on LDI-DII experimentally and identifying the required sequences in LDI-DII necessary for activation of SCN5A transcription would greatly help design further experiments to understand the relevance of our results in more physiologic contexts. While acknowledging these weaknesses, this report raises the intriguing possibility that mutations and post-translational modifications of LDI-DII may control sodium channel activity not only at the electrophysiological level but also at the gene expression level. Bearing in mind that 1) the exact role of LDI-DII remains to be fully explored, 2) there are at least 63 disease-causing mutations in LDI-DII,20 and 3) there are 15–20 phosphorylation sites,21,22 as well as 3 arginine methylation sites (R513, R526 and R680)9 in LDI-DII, our findings provide a new lens to look at the involvement of LDI-DII in NaV1.5 currents and arrhythmogenic diseases.

Methods

Cells and plasmids

Cardiac cells derived from embryonic rat ventricle (H9c2 cells) were maintained under standard cell culture conditions. LDI-DII (residues 416–711) was amplified by PCR from a pCDNA3.1-based plasmid encoding for NaV1.5,9 and cloned as a FLAG-YFP fusion into pCDNA3.1.23 Site-directed mutagenesis was done using the Quikchange kit from Agilent Technologies, following the instructions of the manufacturer (http://www.genomics.agilent.com/en/Site-Directed-Mutagenesis/QuikChange-Lightning/?cid = AG-PT-175andtabId = AG-PR-1162). Sanger sequencing was performed in-house to ensure the introduction of the desired mutations. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher, https://www.thermofisher.com/uk/en/home/brands/product-brand/lipofectamine/lipofectamine-2000.html) and analyzed 24–48 h after transfection.

Prediction of calpain sites in LDI-DII

We used recently published algorithms to predict calpain sites in LDI-DII. The FASTA sequence of LDI-DII was analyzed using the CaMPDB and GPS-CCD databases,12,13 at score thresholds of 0.14 and 0.9, respectively.

Confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde) and permeabilised in 1% Triton-X100. We used an anti-FLAG antibody to detect LDI-DII (Sigma, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/f3165?lang = enandregion = GB), as well as fluorescent phalloidin to mark F-actin (Thermo Fisher, https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/A12379) and DAPI for nuclear staining. Cells were visualised by confocal microscopy in a Zeiss LSM 710.

Reporter assays

Luciferase / Renilla assays were performed as described in the original publication,4 using LDI-DII plasmids. Results from 4 biologic replicates are reported here.

Western blot

H9c2 cells were lysed in 1% NP-40 48 h after transfection. We used an anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, http://www.abcam.com/gfp-antibody-chip-grade-ab290.html) to detect LDI-DII-FLAG-YFP expression. Two biologic replicates were done.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kath Bulmer for excellent technical assistance. The authors thank students who over the years have contributed to the present work, including David Roura and Oliver Taylor.

Funding

DOO acknowledges Rivers state university of Science & Technology Port Harcourt Nigeria, and TETfund Nigeria (Academic staff Training and development unit) for funding. AT acknowledges a predoctoral fellowship from University of Girona (BR2012/47), MP-A a predoctoral fellowship from Generalitat de Catalunya (2014FI_B 00586). This work was supported by the University of Hull, the Spanish Government (SAF2011–27627) and 7PM-PEOPLE Marie Curie International Reintegration Grant (PIRG07-GA-2010–268395).

References

- [1].Gabelli SB, Yoder JB, Tomaselli GF, Amzel LM. Calmodulin and Ca(2+) control of voltage gated Na(+) channels. Channels (Austin) 2016; 10(1):45-54; PMID:26218606; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19336950.2015.1075677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Papadatos GA, Wallerstein PM, Head CE, Ratcliff R, Brady PA, Benndorf K, Saumarez RC, Trezise AE, Huang CL, Vandenberg JI, et al.. Slowed conduction and ventricular tachycardia after targeted disruption of the cardiac sodium channel gene Scn5a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99:6210-5; PMID:11972032; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.082121299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Priest BT, McDermott JS. Cardiac ion channels. Channels (Austin) 2015; 9(6):352-9; PMID:26556552; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19336950.2015.1076597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tarradas A, Pinsach-Abuin ML, Mackintosh C, Llorà-Batlle O, Pérez-Serra A, Batlle M, Pérez-Villa F, Zimmer T, Garcia-Bassets I, Brugada R, et al.. Transcriptional regulation of the sodium channel gene (SCN5A) by GATA4 in human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2017; 102:74-82; PMID:27894866; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Payandeh J, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 2011; 475(7356):353-8; PMID:21743477; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sula A, Booker J, Ng LC, Naylor CE, DeCaen PG, Wallace BA. The complete structure of an activated open sodium channel. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14205; PMID:28205548; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms14205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shen H, Zhou Q, Pan X, Li Z, Wu J, Yan N. Structure of a eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel at near-atomic resolution. Science 2017; 355(6328):eaal4326; PMID:28183995; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aal4326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Onwuli DO, Beltran-Alvarez P. An update on transcriptional and post-translational regulation of brain voltage-gated sodium channels. Amino Acids 2016; 48(3):641-51; PMID:26503606; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00726-015-2122-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beltran-Alvarez P, Pagans S, Brugada R. The cardiac sodium channel is post-translationally modified by arginine methylation. J Proteome Res 2011; 10(8):3712-9; PMID:21726068; https://doi.org/ 10.1021/pr200339n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Paillart C, Boudier JL, Boudier JA, Rochat H, Couraud F, Dargent B. Activity-induced internalization and rapid degradation of sodium channels in cultured fetal neurons. J Cell Biol 1996; 134(2):499-509; PMID:8707833; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.134.2.499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].von Reyn CR, Mott RE, Siman R, Smith DH, Meaney DF. Mechanisms of calpain mediated proteolysis of voltage gated sodium channel α-subunits following in vitro dynamic stretch injury. J Neurochem 2012; 121(5):793-805; PMID:22428606; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07735.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].duVerle D, Takigawa I, Ono Y, Sorimachi H, Mamitsuka H. CaMPDB: a resource for calpain and modulatory proteolysis. Genome Inform 2010; 22:202-13; PMID:20238430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu Z, Cao J, Gao X, Ma Q, Ren J, Xue Y. GPS-CCD: a novel computational program for the prediction of calpain cleavage sites. PLoS One 2011; 6(4):e19001; PMID:21533053; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0019001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim DY, Ingano LA, Carey BW, Pettingell WH, Kovacs DM. Presenilin/gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channel beta2-subunit regulates cell adhesion and migration. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(24):23251-61; PMID:15833746; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M412938200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim DY, Carey BW, Wang H, Ingano LA, Binshtok AM, Wertz MH, Pettingell WH, He P, Lee VM, Woolf CJ, et al.. BACE1 regulates voltage-gated sodium channels and neuronal activity. Nat Cell Biol 2007; 9(7):755-64; PMID:17576410; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wong HK, Sakurai T, Oyama F, Kaneko K, Wada K, Miyazaki H, Kurosawa M, De Strooper B, Saftig P, Nukina N. beta Subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels are novel substrates of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme (BACE1) and gamma-secretase. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(24):23009-17; PMID:15824102; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M414648200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Baroni D, Picco C, Barbieri R, Moran O. Antisense-mediated post-transcriptional silencing of SCN1B gene modulates sodium channel functional expression. Biol Cell 2014; 106(1):13-29; PMID:24138709; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/boc.201300040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen Y, Sánchez A, Rubio ME, Kohl T, Pardo LA, Stühmer W. Functional K(v)10.1 channels localize to the inner nuclear membrane. PLoS One 2011; 6(5):e19257; PMID:21559285; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0019257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].von Reyn CR, Spaethling JM, Mesfin MN, Ma M, Neumar RW, Smith DH, Siman R, Meaney DF. Calpain mediates proteolysis of the voltage-gated sodium channel alpha-subunit. J Neurosci 2009; 29(33):10350-6; PMID:19692609; https://doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2339-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Shaw K, Phillips A, Cooper DN. The human gene mutation database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum Genet 2014; 133:1-9; PMID:24077912; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00439-013-1358-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baek JH, Rubinstein M, Scheuer T, Trimmer JS. Reciprocal changes in phosphorylation and methylation of mammalian brain sodium channels in response to seizures. J Biol Chem 2014; 289(22):15363-73; PMID:24737319; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M114.562785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Herren AW, Weber DM, Rigor RR, Margulies KB, Phinney BS, Bers DM. CaMKII Phosphorylation of Na(V)1.5: Novel in vitro sites identified by mass spectrometry and reduced S516 phosphorylation in human heart failure. J Proteome Res 2015; 14(5):2298-311; PMID:25815641; https://doi.org/ 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Beltran-Alvarez P, Espejo A, Schmauder R, Beltran C, Mrowka R, Linke T, Batlle M, Pérez-Villa F, Pérez GJ, Scornik FS, et al.. Protein arginine methyl transferases-3 and -5 increase cell surface expression of cardiac sodium channel. FEBS Lett 2013; 587(19):3159-65; PMID:23912080; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]