Tanaka et al. show that BCL6 corepressor (BCOR) targets a significant portion of NOTCH1 targets in thymocytes to restrain their activation. Conditional deletion of the BCL6-binding domain of BCOR results in induction of Notch-dependent acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia in mice.

Abstract

Recurrent inactivating mutations have been identified in various hematological malignancies in the X-linked BCOR gene encoding BCL6 corepressor (BCOR); however, its tumor suppressor function remains largely uncharacterized. We generated mice missing Bcor exon 4, expressing a variant BCOR lacking the BCL6-binding domain. Although the deletion of exon 4 in male mice (BcorΔE4/y) compromised the repopulating capacity of hematopoietic stem cells, BcorΔE4/y thymocytes had augmented proliferative capacity in culture and showed a strong propensity to induce acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), mostly in a Notch-dependent manner. Myc, one of the critical NOTCH1 targets in T-ALL, was highly up-regulated in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL cells. Chromatin immunoprecipitation/DNA sequencing analysis revealed that BCOR was recruited to the Myc promoter and restrained its activation in thymocytes. BCOR also targeted other NOTCH1 targets and potentially antagonized their transcriptional activation. Bcl6-deficient thymocytes behaved in a manner similar to BcorΔE4/y thymocytes. Our results provide the first evidence of a tumor suppressor role for BCOR in the pathogenesis of T lymphocyte malignancies.

Introduction

BCOR was originally identified as a corepressor of BCL6, a key transcriptional factor required for development of germinal center B cells (Huynh et al., 2000; Klein and Dalla-Favera, 2008). BCOR is located on chromosome X, and mutations in BCOR were initially identified in patients with X-linked inherited diseases Lenz microphthalmia and oculo-facio-cardio-dental (OFCD) syndrome (Ng et al., 2004). The mutations include stop codon gains and frame-shift insertions or deletions, indicating that they cause the loss of BCOR function. Mesenchymal stem cells isolated from a patient with OFCD exhibited increased osteo-dentinogenic potential in culture (Fan et al., 2009). However, the lack of OFCD phenotypes in Bcl6-deficient mice (Yoshida et al., 1999) suggested the involvement of non-BCL6 pathways in the developmental consequences of Bcor mutations. Recent extensive analyses of the BCOR complex revealed that BCOR also copurifies with RING1B, PCGF1, and KDM2B and functions as a component of the noncanonical polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1), PRC1.1, which monoubiquitinates histone H2A (Gearhart et al., 2006; Sánchez et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2012).

Recent whole-exome sequencing has identified somatic BCOR mutations in various hematological diseases. BCOR mutations have been reported in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with normal karyotype (3.8%), secondary AML (3.5%), myelodysplastic syndrome (4.2%), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (7.4%), and extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (21–32%; Grossmann et al., 2011; Damm et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015; Lindsley et al., 2015; Dobashi et al., 2016). Most of the BCOR mutations result in stop codon gains, frame-shift insertions or deletions, splicing errors, and gene loss, leading to the loss of BCOR function (Damm et al., 2013). BCOR mutations also result in reduced mRNA levels, possibly because of activation of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway (Damm et al., 2013). The closely related homolog BCOR-like 1 (BCORL1) has been implicated in AML and myelodysplastic syndrome in a manner similar to BCOR (Li et al., 2011; Damm et al., 2013). Somatic mutations in BCOR or BCORL1 have also been identified in 9.3% of patients with aplastic anemia and correlated with a better response to immunosuppressive therapy and longer and higher rates of overall and progression-free survival (Yoshizato et al., 2015). Furthermore, BCOR mutations have been found in retinoblastoma, bone sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (Pierron et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012a; Kelsey, 2015).

BCOR has been shown to restrict myeloid proliferation and differentiation in culture using conditional loss-of-function alleles of Bcor in which exons 9 and 10 are missing. This mutant Bcor allele generates a truncated protein that lacks the region required for the interaction with PCGF1, a core component of PRC1.1, and mimics some of the pathogenic mutations observed in patients with OFCD and hematological malignancies (Cao et al., 2016). The tumor suppressor function of Bcor has recently been confirmed in vivo using Myc-driven lymphomagenesis in mice (Lefebure et al., 2017). However, limited information is available on its role in hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies. In the present study, we investigated the function of BCOR using mice expressing variant BCOR, which cannot bind to BCL6, and revealed a critical role for BCOR in restricting transformation of hematopoietic cells.

Results and discussion

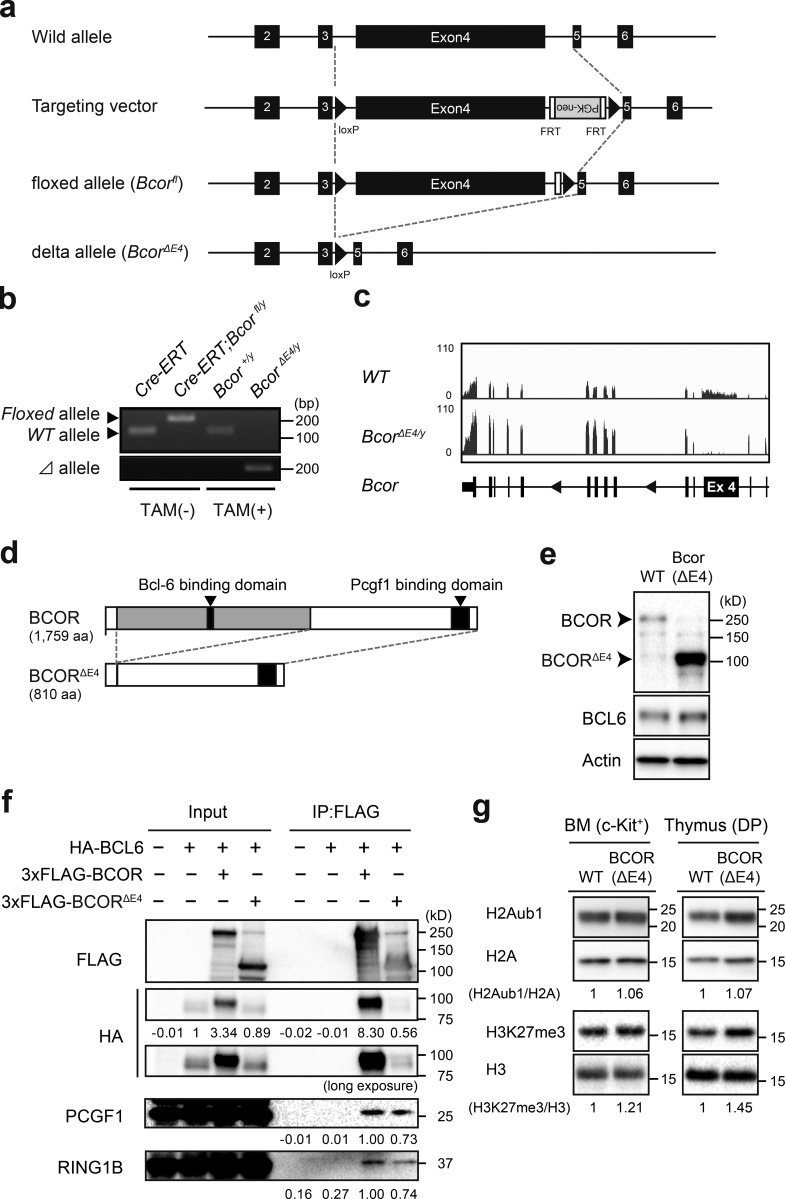

Generation of mice expressing BCOR that cannot bind to BCL6

To understand the physiological role of BCOR as a BCL6 corepressor, we generated mice harboring a Bcorfl mutation in which exon 4 encoding the BCL6-binding site (Ghetu et al., 2008) was floxed (Fig. 1 a), and then crossed Bcorfl mice with Rosa26::Cre-ERT (Cre-ERT) mice. We transplanted BM cells from Cre-ERT control (WT) and Bcorfl/y;Cre-ERT CD45.2 male mice (Bcor is located on the X chromosome) without competitor cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice and deleted Bcor exon 4 by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen at 4 wk posttransplantation. We hereafter refer to the recipient mice reconstituted with WT and BcorΔE4/y cells as WT and BcorΔE4/y mice, respectively. We confirmed the efficient deletion of Bcor exon 4 in hematopoietic cells from BcorΔE4/y mice by genomic PCR (Fig. 1 b). RNA-sequence analysis of lineage-marker (Lin)− Sca-1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) revealed the specific deletion of Bcor exon 4 (Fig. 1 c). Bcor lacking exon 4 generates a short form of BCOR protein (BCORΔE4) that lacks the BCL6 binding site but still retains the binding site for PCGF1, a component of PRC1.1 (Fig. 1 d). Western blot analysis detected a short form of BCOR in thymocytes from BcorΔE4/y mice (Fig. 1 e). To test physical interactions between BCL6 and BCORΔE4, we cotransfected 293T cells with plasmids encoding HA-tagged BCL6 and Flag-tagged BCOR and performed immunoprecipitation. Full-length BCOR readily coimmunoprecipitated with BCL6, but BCORΔE4 scarcely did. In contrast, full-length BCOR and BCORΔE4 both retained binding to PCGF1 and RING1B, components of PRC1.1, suggesting that the deletion of Bcor exon 4 does not compromise the function of PRC1.1 (Fig. 1 f). Interestingly, the stabilization of BCL6, which may be induced by interaction with exogenous BCOR, was observed in cells transfected with full-length Bcor but not BcorΔE4 (Fig. 1 f). Western blot analysis revealed that BcorΔE4/y BM c-Kit+ progenitors and CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes had polycomb histone modifications (H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me3) at levels similar to WT (Fig. 1 g).

Figure 1.

Generation of mice expressing BCOR that cannot bind to BCL6. (a) Strategy for making a conditional knockout allele for Bcor exon 4 by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. FRT recombinase was used to remove the PGK-Neo cassette. (b) Efficient deletion of Bcor exon 4 in hematopoietic cells detected by genomic PCR. Deletion of Bcor exon 4 in Cre-ERT;Bcorfl/y PB Mac1+Gr-1+ myeloid cells from recipient mice repopulated with Cre-ERT;Bcorfl/y hematopoietic cells before and 4 wk after tamoxifen treatment. Floxed, floxed Bcor allele; Δ, floxed Bcor allele after the removal of exon 4 by Cre recombinase. (c) Snapshots of RNA-seq signals at the Bcor gene locus in WT and BcorΔE4/y LSK cells isolated from recipient mice repopulated with BcorΔE4/y hematopoietic cells. The structure of the Bcor gene locus including relevant exons is indicated at the bottom. (d) Schematic representation of the BCORΔE4 protein. (e) BCORΔE4 protein in the thymus of BcorΔE4/y mice detected by Western blot analysis. WT and BCORΔE4 proteins are indicated by arrowheads. (f) BCORΔE4 retains the interaction with PCGF1 and RING1B, but not BCL6. 293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged BCL6 and 3xFlag-tagged BCOR or BCORΔE4, and immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-Flag antibody. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-HA, anti-Flag, anti-PCGF1, or anti-RING1B antibodies. (g) Levels of global H2AK119ub1 in WT and BcorΔE4/y c-Kit+ progenitors and DP thymocytes. Levels of H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me3 were normalized to the amount of H2A and H3, respectively, and are indicated relative to WT values. Representative data from at least two independent experiments are presented (b–g).

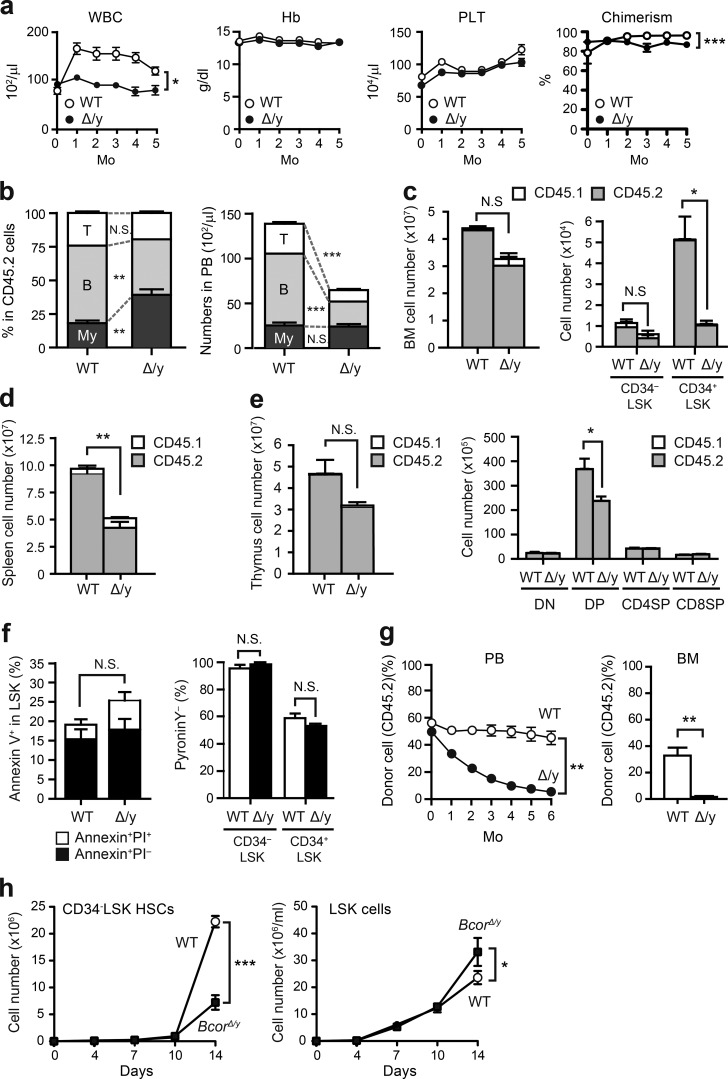

Deletion of Bcor exon 4 impairs the repopulating capacity of hematopoietic stem cells

We first examined hematopoiesis in BcorΔE4/y mice. These mice exhibited leukopenia that was mainly attributed to impaired B lymphopoiesis (Fig. 2, a and b). 6 mo after the deletion of Bcor exon 4, BcorΔE4/y mice showed reductions in the numbers of total BM, CD34−LSK hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), CD34+LSK multipotent progenitors, spleen cells, thymocytes, and DP thymocytes (Fig. 2, c–e). No significant difference was observed in the frequency of apoptotic cells between control and BcorΔE4/y LSK cells (Fig. 2 f). Moreover, the proportion of HSPCs in the G0 stage of the cell cycle did not change (Fig. 2 f). To avoid the proliferative stress caused by BM transplantation, we also deleted Bcor exon 4 in primary Bcorfl/y mice. The mice showed hematopoietic phenotypes similar to those observed in BM transplant mice with the hematopoietic cell-specific deletion (not depicted). We then performed competitive repopulation assays using the same number of test cells and BM competitor cells and found that BcorΔE4/y BM cells were gradually outcompeted by WT BM cells in both peripheral blood (PB) and BM (Fig. 2 g), indicating the impaired repopulating capacity of BcorΔE4/y HSCs. We next purified CD34−LSK HSCs and LSK HSPCs from the BM of WT and BcorΔE4/y mice and evaluated their proliferative capacity in vitro. Although BcorΔE4/y HSCs showed significantly impaired cell growth under culture conditions that supported stem cell proliferation rather than differentiation (stem cell factor [SCF] and thrombopoietin [TPO]), BcorΔE4/y LSK HSPCs demonstrated moderately higher proliferation rates than WT under myeloid culture conditions (SCF+TPO+IL-3+GM-CSF; Fig. 2 h), as reported previously for mice lacking Bcor exons 9 and 10 (Cao et al., 2016). However, a serial methylcellulose replating colony assay did not show any enhancement in the serial replating capacity of BcorΔE4/y LSK cells (not depicted). These results indicate that the deletion of Bcor exon 4 compromises the repopulation capacity of HSCs both in vitro and in vivo, but not the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Figure 2.

Deletion of Bcor exon 4 impairs the repopulating capacity of HSCs. (a) PB cell counts in WT and BcorΔE4/y mice. BM cells (5 × 106) from Bcor+/+;Cre-ERT and Bcorfl/y;Cre-ERT CD45.2 mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. To delete Bcor exon 4, 100 µl tamoxifen (10 mg/ml) was intraperitoneally injected once a day for five consecutive days (at 4 wk posttransplantation). White blood cell (WBC), hemoglobin (Hb), and platelet (PLT) counts in the PB from WT (n = 4) and BcorΔE4/y (n = 12) mice after injection of tamoxifen are shown. Chimerism of CD45.2+ donor-derived cells is indicated at right. (b) Proportions of myeloid cells (My; Mac-1+ and/or Gr-1+), B220+ B cells, and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells among CD45.2+ donor-derived hematopoietic cells and their absolute numbers in the PB from WT (n = 7) and BcorΔE4/y (n = 17) mice 4 mo after the injection of tamoxifen. (c) Absolute numbers of total BM cells, CD34−LSK HSCs, and CD34+LSK HPCs in a unilateral pair of femur and tibia 6 mo after the injection of tamoxifen (n = 4). (d and e) Absolute numbers of total spleen cells (d) and total thymocytes and double-negative, DP, CD4 SP, and CD8 SP thymocytes (e) 6 mo after the injection of tamoxifen (n = 4). CD45.1+ host and CD45.2+ donor-derived hematopoietic cells are indicated in c–e. (f) Proportion of apoptotic cells in the LSK fraction of BM and pyronin Y− G0 cells in CD34−LSK HSCs and CD34+LSK HPCs 3 mo after the injection of tamoxifen (n = 3). (g) Competitive repopulating capacity of BcorΔE4/y hematopoietic cells. CD45.2 BM cells (2 × 106) from Bcor+/y;Cre-ERT and Bcorfl/y;Cre-ERT mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice along with the same number of CD45.1 WT BM cells. Bcor exon 4 was deleted by injecting tamoxifen (at 4 wk posttransplantation). The chimerism of CD45.2 donor cells in the PB was monitored monthly, whereas that in the BM was examined 6 mo after the injection of tamoxifen (n = 4). (h) Growth of WT and BcorΔE4/y CD34−LSK HSCs and LSK HSPCs in culture. HSCs and HSPCs were cultured in triplicate under stem cell–supporting culture conditions (SCF+TPO) and myeloid cell culture conditions (SCF+TPO+IL-3+GM-CSF), respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test; N.S., not significant. Representative data from three independent experiments are presented (a–h).

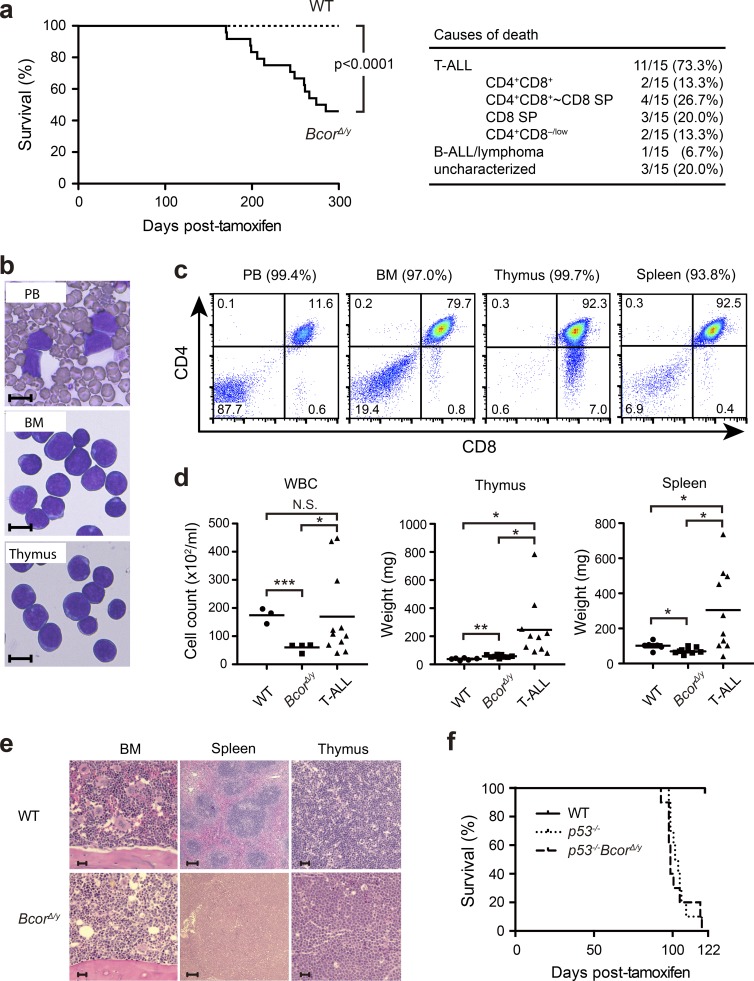

Deletion of Bcor exon 4 induces acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia

During an observation period of 300 d after the deletion of Bcor exon 4, 50% of BcorΔE4/y mice developed lethal acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), whereas only one mouse developed B-ALL/lymphoma (Fig. 3 a). Moribund mice with T-ALL showed expansion of lymphoblasts, which were mostly DP or CD8 single-positive (SP; Fig. 3, a–c and e). T-ALL cells were also detected in the PB, BM, thymus, and spleen to varying degrees (Fig. 3, b–e). All the T-ALL mice showed high chimerism of donor-derived cells (PB, 89.0 ± 4.6%; BM, 92.3 ± 4.3%; thymus, 98.8 ± 0.5%; and spleen, 97.4 ± 0.8%; n = 8–9). Most T-ALL involved the thymus, but 20% had no or minimal involvement of the thymus, suggesting BM origin of the disease. It was previously reported that loss of p53 induces the transformation of thymocytes, leading to the development of thymic T cell lymphoma characterized by the expansion of DP or CD8 SP lymphoblasts in mice (Donehower et al., 1992; Jacks et al., 1994), and promotes transformation of cells with insufficient tumor suppressor functions (Jonkers et al., 2001; Celeste et al., 2003). To test whether the loss of p53 accelerates leukemogenesis in BcorΔE4/y mice, we generated BcorΔE4/yp53−/− mutants. Although all p53−/− mice developed thymic T cell lymphoma, BcorΔE4/yp53−/− mice developed T-ALL (60%) in addition to thymic T cell lymphoma (40%; Fig. 3 f). BcorΔE4/yp53−/− T-ALL showed phenotypes that were similar to those of BcorΔE4/y T-ALL (not depicted), albeit with markedly earlier onset (Fig. 3, a and f). Although BcorΔE4 did not accelerate the development of thymic T cell lymphoma induced by the loss of p53, these results suggest that BcorΔE4 and inactive p53 alleles cooperate in the development of T-ALL in mice.

Figure 3.

Deletion of Bcor exon 4 induces acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of WT (n = 23) and BcorΔE4/y (n = 20) mice after the injection of tamoxifen. Data from four independent experiments were combined. ***, P < 0.001 by log-rank test. The causes of death in BcorΔE4/y mice are summarized in a table. (b) Smear preparation of the PB and cytospin preparations of the BM and thymus of a representative BcorΔE4/y T-ALL mouse observed after May-Giemsa staining. Bars, 10 µm. (c) Flow cytometric profiles of the PB, BM, spleen, and thymus from a representative BcorΔE4/y T-ALL mouse. Chimerism of donor-derived cells is indicated in parentheses. (d) PB counts and spleen and thymus weights in moribund BcorΔE4/y T-ALL mice and WT and BcorΔE4/y mice 300 d after the injection of tamoxifen (PB: WT, n = 3; BcorΔE4/y, n = 4; BcorΔE4/y T-ALL, n = 11; thymus: WT, n = 6; BcorΔE4/y, n = 9; BcorΔE4/y T-ALL, n = 10; spleen: WT, n = 6; BcorΔE4/y, n = 9; BcorΔE4/y T-ALL, n = 10). Bars in scatter diagrams indicate median values. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test; N.S., not significant. (e) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of thymus, spleen, and BM sections from WT and BcorΔE4/y T-ALL mice. Bars: (BM and thymus) 20 µm; (spleen) 100 µm. (f) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of p53−/− and p53−/−BcorΔE4/y mice (n = 10 each). Representative data from two independent experiments are presented.

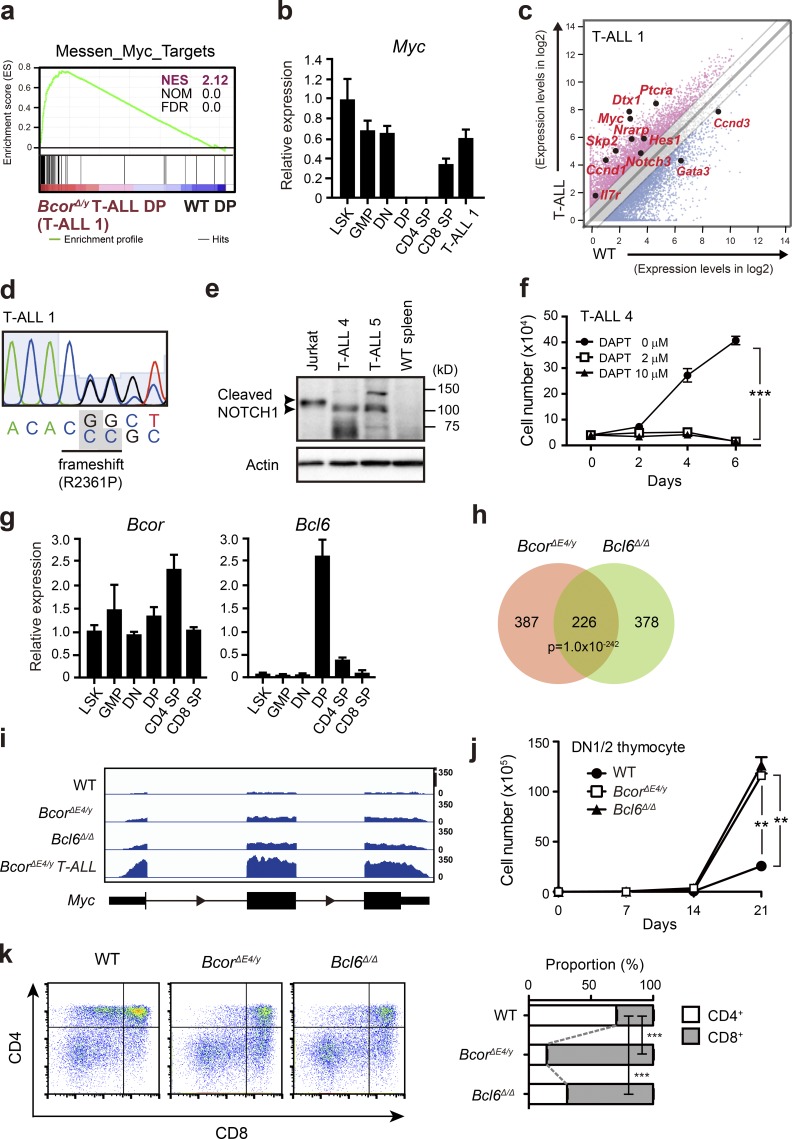

Myc is activated in BcorΔE4/y DP thymocytes and T-ALL

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for BcorΔE4/y T-ALL, we performed RNA sequence analysis of BcorΔE4/y DP leukemic blasts from the thymus of moribund mice (T-ALL no. 1) and WT DP thymocytes. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed the stronger enrichment of MYC target genes in BcorΔE4/y DP leukemic blasts than in WT DP thymocytes (Fig. 4 a). Myc is one of the potent oncogenes implicated in T-ALL (Belver and Ferrando, 2016). It plays an important role in the control of cell growth downstream of NOTCH1 and pre-TCR signaling during early T cell development. NOTCH1 directly binds to a long-range distal Myc enhancer and activates Myc, which is crucial for T cell development and also the initiation and maintenance of NOTCH-dependent T-ALL (Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2014; Herranz et al., 2015). Although Myc is completely transcriptionally repressed in DP thymocytes that lose proliferative capacity, it was strongly up-regulated in BcorΔE4/y DP leukemic blasts (T-ALL no. 1; Fig. 4 b) and DP and CD8 SP blasts from T-ALL nos. 2 and 3, respectively (not depicted).

Figure 4.

Activation of Myc in BcorΔE4/y DP thymocytes and T-ALL. (a) GSEA plot for the MYC target gene set demonstrating significant positive enrichment in BcorΔE4/y DP T-ALL cells relative to WT DP thymocytes. NES, NOM, and FDR are indicated. Red and blue colors represent positive (up-regulated in the given genotype relative to WT) and negative (up-regulated in WT relative to the given genotype) enrichment, respectively. (b) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Myc in various hematopoietic cell fractions and BcorΔE4/y DP T-ALL cells. Hprt1 was used to normalize the amount of input RNA. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Representative data from two independent experiments are presented. (c) Scatter diagram showing RNA sequence data. Signal levels of RefSeq genes (RPKM+1 in log2) in BcorΔE4/y DP T-ALL cells and WT DP thymocytes are plotted. Light gray lines represent the boundaries for a twofold increase and twofold decrease. Representative direct target genes of NOTCH1 are shown as red dots. (d) Chromatogram traces showing a Notch1 mutation in exon 34 (T-ALL no. 1). The variant bases are listed underneath and indicated in gray boxes. (e) Cleaved NOTCH1 protein in T-ALL cells detected by Western blot analysis. Cleaved NOTCH1 proteins in human T-ALL cells (Jurkat) and BCORΔE4 T-ALL cells (CD8 SP and CD4 SP T-ALL cells from the spleens of T-ALL nos. 4 and 5, respectively) are indicated by arrowheads. Actin served as a loading control. Representative data from two independent experiments are presented. (f) In vitro proliferation of BcorΔE4/y T-ALL cells. CD8 SP T-ALL cells from the spleen of T-ALL no. 4 were cultured on TSt-4 stromal cells in the presence of a γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures. Representative data from two independent experiments are presented. ***, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test. (g) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Bcor and Bcl6 in various hematopoietic cell fractions. Hprt1 was used to normalize the amount of input RNA. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Representative data from two independent experiments are presented. (h) Venn diagram of RefSeq genes up-regulated in DP thymocytes from BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ mice 4 wk after the injection of tamoxifen (more than twofold relative to the WT control). The numbers of genes in each group are indicated. The overlap between the two gene sets is statistically significant (P < 1 × 10−242). (i) Snapshots of RNA sequence signals at the Myc gene locus in WT, BcorΔE4/y, and Bcl6Δ/Δ DP thymocytes and BcorΔE4/y DP T-ALL cells. The structure of the Myc gene locus is indicated at the bottom. (j) In vitro proliferation of BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ thymocytes. DN1/2 thymocytes from BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ mice were cultured on TSt-4/DLL stromal cells in the presence of 10 ng/ml SCF, Flt3L, and IL-7. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures. (k) In vitro differentiation of BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ thymocytes. Culture conditions in j were switched to differentiation conditions by reducing the cytokine concentration to 2 ng/ml on day 14 of culture, and cells were cultured for a further 7 d. Differentiation was evaluated by flow cytometric analyses. Representative CD4 and CD8 expression profiles are depicted. The proportions of CD4+CD8+, CD4+CD8−, and CD4−CD8+ thymocytes are as follows: WT, 25.8 ± 1.0, 21.7 ± 0.6, and 9.1 ± 0.1; BcorΔE4/y, 17.1 ± 0.6, 4.1 ± 0.1, and 24.0 ± 0.2; and Bcl6Δ/Δ, 14.1 ± 0.8, 7.2 ± 0.2, and 16.3 ± 0.5, respectively (n = 3). The proportions of CD4 SP and CD8 SP thymocytes are shown at right. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test. Representative data from three independent experiments are presented (j and k).

We then examined whether the active NOTCH1 pathway is involved in this process. Although NOTCH1 target gene sets were not significantly enriched in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL in GSEA (not depicted), many of the representative direct targets of NOTCH1 were up-regulated in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL in addition to Myc, such as Hes1, Ptcra, Ccnd1, Skp2, and Il7r (Fig. 4 c), suggesting that NOTCH1 signaling is augmented in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL. Sanger sequencing of exons 26–28 and 34 of Notch1, in which the majority of activating NOTCH1 mutations are found in human T-ALL, revealed a mutation in exon 34 in one of five T-ALLs (T-ALL no. 1; Fig. 4 d). This mutation caused frameshift, which resulted in truncation of the PEST domain in the C-terminal region of the protein. We also found Notch1 deletions in two of five T-ALLs (T-ALL nos. 3 and 4), which remove exon 1 and the proximal promoter (Fig. S1 a), leading to ligand-independent NOTCH1 activation (type 1 deletions; Ashworth et al., 2010). None of the five T-ALLs had activating Notch1 transcripts, in which exon 1 is spliced out of frame to 3′ Notch1 exons (type 2 deletions; Fig. S1 b; Ashworth et al., 2010). Western blotting for activated NOTCH1 revealed accumulation of cleaved NOTCH1 in CD8 SP and CD4 SP T-ALL cells from the spleens of T-ALL nos. 4 and 5, respectively (Fig. 4 e). Correspondingly, immunohistochemical analysis of the spleen of T-ALL no. 4 showed nuclear accumulation of cleaved NOTCH1 (Fig. S2). Finally, we treated leukemic cells (T-ALL no. 4) with N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT), a γ-secretase inhibitor, and confirmed marked inhibition of cell growth in culture (Fig. 4 f). All these findings, which are summarized in Fig. S1 b, suggest that BCORΔE4 collaborates with active NOTCH1 to induce T-ALL.

During the differentiation of T lymphocytes in the thymus, Bcl6 is expressed in a manner that is reciprocal to Myc. Bcl6 is turned on in DP thymocytes in which Myc is shut off. In contrast, Bcor is expressed throughout differentiation (Fig. 4 g). We generated Bcl6Δ/Δ mice reconstituted with Bcl6fl/fl;Cre-ERT BM cells followed by treatment with tamoxifen. The Bcl6Δ mutant allele lacks exons 7–9, which encode the C-terminal zinc finger domains ZF1 to ZF5. The resultant protein cannot bind to DNA (Kaji et al., 2012). RNA sequence analyses of DP thymocytes from BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ mice demonstrated significantly overlapping genes derepressed from those in WT, including Myc (Fig. 4 h and Table S1 a). Myc was moderately up-regulated in both BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ DP thymocytes, albeit at lower levels than those in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL DP cells (Fig. 4 i). GSEA revealed that the MYC target gene signature was positively enriched in BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ DP thymocytes (normalized enrichment score [NES] 1.66, nominal p-value [NOM] 0, and false discovery rate [FDR] 0.3; NES 2.06, NOM 0, and FDR 0, respectively).

We next purified CD4CD8 double-negative 1 (DN1) and DN2 thymocytes from BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ thymocytes and cultured them on TSt-4/DLL stromal cells expressing the NOTCH ligand, delta-like 1 (DLL1). BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ DN1/2 thymocytes showed higher proliferative rates under conditions that support thymocyte proliferation (Fig. 4 j). Furthermore, under conditions that promote thymocyte differentiation, BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ thymocytes preferentially differentiated into CD8 SP thymocytes (Fig. 4 k). These differentiation profiles of BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ thymocytes correlated well with that of BcorΔE4/y T-ALL cells, which preferentially showed the DP to CD8 SP phenotype.

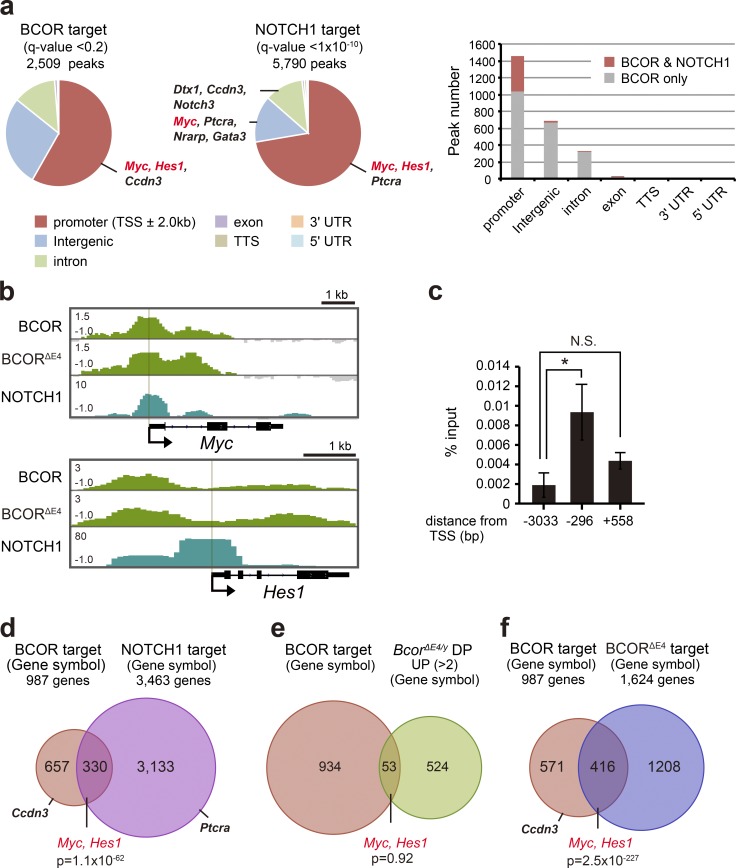

BCOR targets Myc and other NOTCH1 targets in DP thymocytes

To identify BCOR targets in thymocytes, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation/DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis of BCOR using total thymocytes containing DP thymocytes as the major cell population. We detected 2,509 significant binding peaks of BCOR, the majority of which were located on the promoter region around the transcriptional start site (TSS; TSS ± 2.0 kb; Fig. 5 a and Table S1 b). Mapping of NOTCH1 peaks detected in T-ALL cells (Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2014) revealed that a large number of BCOR peaks were located in close proximity to NOTCH1 peaks (±1.0 kb) at the promoter regions but not in the intergenic regions that contain enhancer elements (Fig. 5 a). One of the representative NOTCH targets, Myc, was identified as a BCOR target in DP thymocytes (Fig. 5, a and b). A manual ChIP analysis confirmed the binding of BCOR to the Myc promoter (Fig. 5 c). BCL6 has also been reported to transcriptionally repress Myc in pre-BII cells in which Bcl6 is strongly up-regulated downstream of the pre-B cell receptor signal (Nahar et al., 2011). Interestingly, BCOR appeared to reside on the Myc promoter in close proximity to NOTCH1 detected in T-ALL cells (Fig. 5 b), but BCOR did not bind to the long-range distal Myc enhancer, which binds NOTCH complexes and physically interacts with the Myc promoter in T-ALL cells (Fig. 5 a; Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2014; Herranz et al., 2015). Further comparisons of the binding sites of BCOR in DP thymocytes and NOTCH1 in DP T-ALL cells (Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2014) revealed that a large number of gene promoters had both BCOR and NOTCH1 peaks in close proximity (≤1.0 kb; Fig. 5, a and d), suggesting that BCOR and NOTCH regulate many genes reciprocally in the thymocytes including the representative NOTCH1 targets Myc and Hes1 (Fig. 5, b and d; and Table S1 c). These results suggest that BCOR antagonizes the transcriptional activation of T-ALL–related oncogenes by NOTCH1. However, most genes bound by BCOR at their promoters were not significantly derepressed in BcorΔE4/y DP thymocytes (Fig. 5 e and Table S1 c), indicating that the loss of BCOR binding to BCL6 has minimal impact on the transcription of BCOR targets in a physiological setting in T lymphocytes. BCL6 may function as a repressor by recruiting histone deacetylases SMRT and NCOR, even in the absence of BCOR. Furthermore, the BCORΔE4/y protein stayed at nearly half of the WT BCOR targets in BcorΔE4/y thymocytes (Fig. 5, b and f; and Table S1, c and d), suggesting that the majority of BCOR is recruited to its target gene loci independently of physical binding to BCL6, possibly as a component of PRC1.1. Because global levels of the polycomb histone marks, H2Aub1 and H3K27me3, did not change in BcorΔE4/y thymocytes (Fig. 1 g), BCOR target genes in BcorΔE4/y thymocytes may still remain under the control of repressive polycomb histone modifications.

Figure 5.

BCOR targets Myc and other NOTCH1 targets in DP thymocytes. (a) Distribution of ChIP-seq peaks of BCOR in thymocytes (q-value < 0.2) and NOTCH1 in T-ALL cells (data were retrieved from Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2014; q-value < 10−10) in the indicated regions (left and middle, respectively). Representative NOTCH1 target genes are indicated. Number of BCOR peaks with and without NOTCH1 peaks in close proximity (±1.0 kb) are depicted at right. (b) Snapshots of the ChIP-seq signals of BCOR and BCORΔE4/y at the Myc and Hes1 gene loci in WT and BcorΔE4/y thymocytes, respectively, and those of NOTCH1 in T-ALL cells. The structures of Myc and Hes1 gene loci including relevant exons are indicated at the bottom of each related snapshot. (c) Manual ChIP assays for Bcor at the Myc locus using an anti-BCOR antibody. The relative amounts of immunoprecipitated DNA are depicted as a percentage of input DNA. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student’s t test; N.S., not significant. (d) Venn diagram of BCOR target genes in DP thymocytes and NOTCH1 target in T-ALL cells (Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2014) at the promoter region. The overlapping genes had BCOR and NOTCH1 peaks at their promoters in close proximity (≤1.0 kb). Representative NOTCH1 target genes are indicated. (e) Venn diagram of BCOR target genes at promoters and genes derepressed more than twofold in BcorΔE4/y DP thymocytes from WT DP thymocytes. Representative NOTCH1 target genes are indicated. (f) Venn diagram of the target genes of BCOR and BCORΔE4/y in WT and BcorΔE4/y thymocytes, respectively. Representative data from two independent experiments are presented (a–f).

In this study, we provide the first evidence of a tumor suppressor function for BCOR in T-lymphocytes in vivo. Loss-of-function mutations in BCOR have been identified in myeloid malignancies. Furthermore, recent studies also identified BCOR mutations in lymphoid malignancies, such as extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (21–32%) and chronic lymphocyte leukemia (2.2%; Landau et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Dobashi et al., 2016). Although BCOR mutations are detected in a significant portion (5–8%) of patients with T cell prolymphocytic leukemia, an aggressive neoplasm of mature T lymphocytes (Kiel et al., 2014; Stengel et al., 2016), they are not common in patients with pediatric T-ALL (1.2%; Seki et al., 2017). Our results indicate that the part of BCOR encoded by exon 4 mediates a tumor suppressor function in T lymphocytes. In germinal center B cells, BCOR functions as a corepressor of BCL6 in the context of a PRC1 complex. EZH2-containing PRC2 and BCL6 cooperate to assemble BCL6-BCOR-PRC1.1-PRC2 repressive complexes to promote lymphomagenesis (Béguelin et al., 2016). In contrast, our results indicate a tumor suppressor function for BCOR in T lymphocytes. Nevertheless, it is important to note that many of the components of PRC2 are inactivated by somatic gene mutations in T lymphocytes (Ntziachristos et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012b; Kiel et al., 2014; Stengel et al., 2016). These findings suggest that BCL6 cooperates with the BCOR-containing PRC1 in T lymphocytes in a manner similar to B lymphocytes, but targets different genes. In this regard, it would be intriguing to test whether the deletion of Bcl6 or the genes encoding other components of the BCOR-containing PRC1 also induces T-ALL in mice.

In the present study, the results of ChIP-seq analysis on thymocytes revealed that BCOR targets a significant portion of NOTCH1 targets detected in T-ALL cell lines, including Myc and Hes1. These results suggest that BCOR counteracts the oncogenic active NOTCH to restrain transformation. Therefore, the loss of BCOR may potentiate the transactivating ability of active NOTCH, thereby promoting the development of T-ALL. Indeed, BCORΔE4 appeared to collaborate with active NOTCH1 to induce T-ALL. Collectively, our results suggest that BCL6-BCOR-PRC1.1-PRC2 repressive complexes all collaborate to restrain the excessive activation of NOTCH1 target genes in thymocytes.

Materials and methods

Mice and generation of hematopoietic chimeras

The conditional Bcor allele (Bcorfl), which contains LoxP sites flanking Bcor exon 4 containing the BCL6 binding domain, was generated by homologous recombination using R1 embryonic stem cells according to a conventional protocol. Bcorfl mice were backcrossed at least six times onto a C57BL/6 (CD45.2) background. Bcl6 and p53 conditional knockout mice (Bcl6fl/fl and p53fl/fl, respectively) have been described (Jonkers et al., 2001; Kaji et al., 2012). In the conditional deletion of Bcor and Bcl6, mice were crossed with Rosa26::Cre-ERT mice (TaconicArtemis). To generate hematopoietic chimeras, we transplanted WT, Bcorfl/y;Cre-ERT, or Bcl6fl/fl;Cre-ERT BM cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice and deleted Bcor or Bcl6 4 wk posttransplantation by intraperitoneally injecting 100 µl tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil at a concentration of 10 mg/ml for five consecutive days. Littermates were used as controls. C57BL/6 mice congenic for the Ly5 locus (CD45.1) were purchased from Sankyo-Lab Service. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with our institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals and approved by the Review Board for Animal Experiments of Chiba University (approval ID 25-104).

Flow cytometry and antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies recognizing the following antigens were used in flow cytometry and cell sorting: CD45.2 (104), CD45.1(A20), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), CD11b/Mac-1 (M1/70), Ter-119, CD127/IL-7R (A7R34), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4 (L3T4), CD8 (53-6.7), CD34 (RAM34), CD117/c-Kit (2B8), Sca-1 (D7), CD16/32/FcγRII-III (93), γδTCR (GL3), NK1.1 (PK136), CD11c (N418), CD25 (PC61; APC), and CD44 (IM7; PE). Monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD, BioLegend, eBioscience, or Tonbo. In Annexin V staining, cells were suspended in 1× Annexin binding buffer (BD) and stained with FITC Annexin V (BD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To analyze the cell-cycle status, cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml Pyronin Y (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 45 min. Dead cells were eliminated by staining with 1 µg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). All flow cytometric analyses and cell sorting were performed on FACSAria III or FACS Canto II (BD).

Growth and differentiation assays

CD34−LSK HSCs were cultured in S-Clone SF-O3 (Sanko Junyaku) supplemented with 0.1% BSA, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% glutamine/penicillin/streptomycin, 20 ng/ml SCF, and 20 ng/ml TPO (Peprotech). LSK HSPCs were cultured in the presence of 20 ng/ml SCF, TPO, IL-3, and GM-CSF (Peprotech). Using a biotinylated lineage mixture (Gr-1, Mac-1, Ter-119, B220, CD4, CD8α, γδTCR, CD3ε, CD11c, and NK1.1), CD25, and CD44, Lin− CD25−CD44+ DN1 and Lin−CD25+CD44+ DN2 thymocytes were sorted on FACSAria III and then cultured on TSt-4/DLL stromal cells. SCF, IL-7, and Flt3L (Peprotech) were added to cultures at concentrations of 10 ng/ml and 2 ng/ml for growth and differentiation assays, respectively. Primary T-ALL cells from leukemic mice were cultured on TSt-4 stromal cells in the presence of DAPT (Calbiochem).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed by the ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) with an oligo-dT primer. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) using FastStart Universal Probe Master (Roche Applied Science) and the indicated combinations of the Universal Probe Library (Roche Applied Science). All data are presented as relative expression levels normalized to Hprt expression. Primer sequences used were as follows: Bcor forward, 5′-ATGGCGACGCTTCAAAAG-3′, reverse 5′-GGGCTCCACTGGTATCCAC-3′, probe 19; Bcl6 forward, 5′-CCCCACAGCATACAGAGATG-3′, reverse 5′-TTGCAGAAGAAGGTCCCATT-3′, probe 3; Myc forward, 5′-CCTAGTGCTGCATGAGGAGA-3′, reverse 5′-TCCACAGACACCACATCAATTT-3′, probe 77; and Hprt forward, 5′-TCTTCCTCAGACCGCTTTT-3′, reverse 5′-CCTGGTTCATCATCGCTAATC-3′, probe 95.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Plus Micro kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using a SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA kit for Sequencing (Clontech). ds-cDNA was fragmented using S220 Focused ultrasonicator (Covaris), then cDNA libraries were generated using a NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs). Sequencing was performed using HiSeq1500 (Illumina) with a single-read sequencing length of 60 bp. TopHat (version 2.0.13; default parameters) was used to map the reads to the reference genome (UCSC/mm10 or UCSC/hg19) with annotation data from iGenomes (Illumina). Levels of gene expression were quantified using Cuffdiff (Cufflinks version 2.2.1; default parameters).

ChIP assays and ChIP-seq

In ChIP assays, total thymus cells were fixed with 1% PFA at 25°C for 10 min, lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 1% NP-40 substitute, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS), and sonicated using a homogenizer (NR-50M; Micro-tec Co.). After centrifugation, supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an anti-BCOR antibody (Gearhart et al., 2006). Sheep anti–rabbit IgG Dynabeads were used to capture the anti-BCOR antibody. In the ChIP assay, quantitative PCR was performed with an ABI StepOnePlus thermal cycler with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio) and the following primers: −3033 from TSS forward, 5′-TCTCCCTCCCCTTTTTCAGT-3′, reverse 5′-TGGCGTGTCATGAAACAGAT-3′; −296 from TSS forward, 5′-CAGGGCAAGAACACAGTTCA-3′, reverse 5′-GCTCCGGGGTGTAAACAGTA-3′; and 558 from TSS forward, 5′-GAGCTCCTCGAGCTGTTTG-3′, reverse 5′-ACACAGGGAAAGACCACCAG-3′.

ChIP-seq libraries were prepared using a ThruPLEX DNA-seq kit (Rubicon Genomics). Bowtie2 (version 2.2.6; default parameters) was used to map the reads to the reference genome (UCSC/mm10 or UCSC/hg19). Peaks were called using MACS2 v2.1.0 with a q-value of <0.2 (BCOR) or <10−10 (NOTCH1). ChIP peaks that overlapped with those of corresponding input (distance between centers <10 kb) were removed. Reads per million mapped reads (RPM) values of the sequenced reads were calculated every 1,000-bp bin, with a shifting size of 100 bp using Bedtools. To visualize with Integrative Genomics Viewer (Broad Institute), the RPM values of the immunoprecipitated samples were normalized by subtracting the RPM values of the input samples in each bin and converted to a Bigwig file using the Wigtobigwig tool.

Target sequencing of Notch1

Targeted sequencing of Notch1 was performed using previously described primers (Mayle et al., 2015).

Plasmids, Western blot analysis, and immunoprecipitation

3xFlag-mouse Bcor and 3xFlag-Bcor delta exon 4 were subcloned into the lentivirus vector, CSII-EF1-MCS-IRES-Venus. HA-mouse Bcl6 was subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector. To detect nonhistone proteins using Western blot analysis, lysates were prepared as follows to minimize the fragmentation of proteins by sonication. Cells were lysed in 0.1% NP-40 lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl) and centrifuged. The resulting supernatants were kept on ice (solution A). Pellets were resuspended in SDS sample buffer and sonicated using a Bioruptor (Cosmo Bio; solution B). Mixtures of solutions A and B were incubated at 95°C for 10 min. To detect histone proteins, cells were lysed in 2× SDS sample buffer, sonicated, and incubated at 95°C for 10 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and detected by Western blotting using the following antibodies: anti-BCOR (Gearhart et al., 2006), anti-BCL6 (sc-7388; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-actin (clone C-4, SC-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Flag (clone M2, F3165; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-HA (clone 3F10, 11867423001; Roche), anti–cleaved NOTCH1 (4147; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-PCGF1 (183499; Abcam), anti-RING1B (D139-3; MBL), anti-H2AK119ub (8240S; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti–histone H2A (ab18255; Abcam). Protein bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Immobilon Western; Millipore). The sequential reprobing of membranes with antibodies was performed after the removal of primary and secondary antibodies from membranes in 0.2 M glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.5) and/or the inactivation of HRP by 0.1% NaN3. In immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in 0.1% NP-40 lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl) as above. The pellets were resuspended in 0.1% NP-40 lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl) and sonicated (solution C). Mixtures of solution C and supernatant kept on ice were diluted with 0.1% NP-40 lysis buffer (0 mM NaCl) until the final NaCl concentrations reached 150 mM. After centrifugation, the resulting supernatants were used as input lysates for immunoprecipitation, which was performed using anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (A2220; Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to Western blot analysisas described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5. The significance of differences was measured by a Student’s t test. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Significance was taken at values of *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

Deposition of data

RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (accession no. DRA005459).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 provides data of Notch1 status in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL. Fig. S2 shows immunohistochemical data of active NOTCH1 in BcorΔE4/y T-ALL. Table S1, included as a separate Excel file, lists genes up-regulated in BcorΔE4/y and Bcl6Δ/Δ DP thymocytes, Bcor ChIP-seq peaks in DP thymocytes, Notch1 ChIP-seq peaks in DP T-ALL, and BcorΔE4 ChIP-seq peaks in DP thymocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Toshitada Takemori and Anton Berns for providing us with Bcl6 and p53 mutant mice, respectively; Vivian Bardwell for providing BCOR antibodies and reviewing the manuscript; Noriko Yamanaka for technical assistance; Motoo Kitagawa for valuable suggestions; and Ola Mohammed Kamel Rizq for the critical review of our manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, through Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15H02544) and Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Stem Cell Aging and Disease” (25115002) and grants from the Uehara Memorial Foundation, Yasuda Memorial Medical Foundation, and Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: T. Tanaka, Y. Nakajima-Takagi, and K. Aoyama performed the experiments, analyzed results, made the figures, and wrote the manuscript; S. Tara, M. Oshima, A. Saraya, S. Koide, S. Si, I. Manabe, M. Sanada, M. Masuko, and H. Sone assisted with the experiments; M. Nakayama and H. Koseki generated mice; and A. Iwama conceived of and directed the project, secured funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- AML

- acute myeloid leukemia

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DP

- double-positive

- GSEA

- gene set enrichment analysis

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- HSPC

- hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell

- LSK

- Lin- Sca-1+ c-Kit+

- OFCD

- oculo-facio-cardio-dental

- SCF

- stem cell factor

- SP

- single-positive

- T-ALL

- acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia

- TPO

- thrombopoietin

- TSS

- transcriptional start site

References

- Ashworth T.D., Pear W.S., Chiang M.Y., Blacklow S.C., Mastio J., Xu L., Kelliher M., Kastner P., Chan S., and Aster J.C.. 2010. Deletion-based mechanisms of Notch1 activation in T-ALL: Key roles for RAG recombinase and a conserved internal translational start site in Notch1. Blood. 116:5455–5464. 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béguelin W., Teater M., Gearhart M.D., Calvo Fernández M.T., Goldstein R.L., Cárdenas M.G., Hatzi K., Rosen M., Shen H., Corcoran C.M., et al. . 2016. EZH2 and BCL6 cooperate to assemble CBX8-BCOR complex to repress bivalent promoters, mediate germinal center formation and lymphomagenesis. Cancer Cell. 30:197–213. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belver L., and Ferrando A.. 2016. The genetics and mechanisms of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 16:494–507. 10.1038/nrc.2016.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q., Gearhart M.D., Gery S., Shojaee S., Yang H., Sun H., Lin D.C., Bai J.W., Mead M., Zhao Z., et al. . 2016. BCOR regulates myeloid cell proliferation and differentiation. Leukemia. 30:1155–1165. 10.1038/leu.2016.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeste A., Difilippantonio S., Difilippantonio M.J., Fernandez-Capetillo O., Pilch D.R., Sedelnikova O.A., Eckhaus M., Ried T., Bonner W.M., and Nussenzweig A.. 2003. H2AX haploinsufficiency modifies genomic stability and tumor susceptibility. Cell. 114:371–383. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00567-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damm F., Chesnais V., Nagata Y., Yoshida K., Scourzic L., Okuno Y., Itzykson R., Sanada M., Shiraishi Y., Gelsi-Boyer V., et al. . 2013. BCOR and BCORL1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and related disorders. Blood. 122:3169–3177. 10.1182/blood-2012-11-469619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi A., Tsuyama N., Asaka R., Togashi Y., Ueda K., Sakata S., Baba S., Sakamoto K., Hatake K., and Takeuchi K.. 2016. Frequent BCOR aberrations in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 55:460–471. 10.1002/gcc.22348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower L.A., Harvey M., Slagle B.L., McArthur M.J., Montgomery C.A. Jr., Butel J.S., and Bradley A.. 1992. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 356:215–221. 10.1038/356215a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z., Yamaza T., Lee J.S., Yu J., Wang S., Fan G., Shi S., and Wang C.Y.. 2009. BCOR regulates mesenchymal stem cell function by epigenetic mechanisms. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:1002–1009. 10.1038/ncb1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Zhang J., Bonasio R., Strino F., Sawai A., Parisi F., Kluger Y., and Reinberg D.. 2012. PCGF homologs, CBX proteins, and RYBP define functionally distinct PRC1 family complexes. Mol. Cell. 45:344–356. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart M.D., Corcoran C.M., Wamstad J.A., and Bardwell V.J.. 2006. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:6880–6889. 10.1128/MCB.00630-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghetu A.F., Corcoran C.M., Cerchietti L., Bardwell V.J., Melnick A., and Privé G.G.. 2008. Structure of a BCOR corepressor peptide in complex with the BCL6 BTB domain dimer. Mol. Cell. 29:384–391. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann V., Tiacci E., Holmes A.B., Kohlmann A., Martelli M.P., Kern W., Spanhol-Rosseto A., Klein H.U., Dugas M., Schindela S., et al. . 2011. Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of BCOR in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood. 118:6153–6163. 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz D., Ambesi-Impiombato A., Sudderth J., Sánchez-Martín M., Belver L., Tosello V., Xu L., Wendorff A.A., Castillo M., Haydu J.E., et al. . 2015. Metabolic reprogramming induces resistance to anti-NOTCH1 therapies in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Med. 21:1182–1189. 10.1038/nm.3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh K.D., Fischle W., Verdin E., and Bardwell V.J.. 2000. BCoR, a novel corepressor involved in BCL-6 repression. Genes Dev. 14:1810–1823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T., Remington L., Williams B.O., Schmitt E.M., Halachmi S., Bronson R.T., and Weinberg R.A.. 1994. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr. Biol. 4:1–7. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers J., Meuwissen R., van der Gulden H., Peterse H., van der Valk M., and Berns A.. 2001. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 29:418–425. 10.1038/ng747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji T., Ishige A., Hikida M., Taka J., Hijikata A., Kubo M., Nagashima T., Takahashi Y., Kurosaki T., Okada M., et al. . 2012. Distinct cellular pathways select germline-encoded and somatically mutated antibodies into immunological memory. J. Exp. Med. 209:2079–2097. 10.1084/jem.20120127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey R. 2015. Kidney cancer: BCOR mutations that might help in diagnosis of CCSK. Nat. Rev. Urol. 12:416 10.1038/nrurol.2015.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel M.J., Velusamy T., Rolland D., Sahasrabuddhe A.A., Chung F., Bailey N.G., Schrader A., Li B., Li J.Z., Ozel A.B., et al. . 2014. Integrated genomic sequencing reveals mutational landscape of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 124:1460–1472. 10.1182/blood-2014-03-559542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U., and Dalla-Favera R.. 2008. Germinal centres: Role in B-cell physiology and malignancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:22–33. 10.1038/nri2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau D.A., Tausch E., Taylor-Weiner A.N., Stewart C., Reiter J.G., Bahlo J., Kluth S., Bozic I., Lawrence M., Böttcher S., et al. . 2015. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature. 526:525–530. 10.1038/nature15395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Park H.Y., Kang S.Y., Kim S.J., Hwang J., Lee S., Kwak S.H., Park K.S., Yoo H.Y., Kim W.S., et al. . 2015. Genetic alterations of JAK/STAT cascade and histone modification in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma nasal type. Oncotarget. 6:17764–17776. 10.18632/oncotarget.3776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebure M., Tothill R.W., Kruse E., Hawkins E.D., Shortt J., Matthews G.M., Gregory G.P., Martin B.P., Kelly M.J., Todorovski I., et al. . 2017. Genomic characterisation of Eμ-Myc mouse lymphomas identifies Bcor as a Myc co-operative tumour-suppressor gene. Nat. Commun. 8:14581 10.1038/ncomms14581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Collins R., Jiao Y., Ouillette P., Bixby D., Erba H., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K.W., Papadopoulos N., and Malek S.N.. 2011. Somatic mutations in the transcriptional corepressor gene BCORL1 in adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 118:5914–5917. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-356204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley R.C., Mar B.G., Mazzola E., Grauman P.V., Shareef S., Allen S.L., Pigneux A., Wetzler M., Stuart R.K., Erba H.P., et al. . 2015. Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood. 125:1367–1376. 10.1182/blood-2014-11-610543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayle A., Yang L., Rodriguez B., Zhou T., Chang E., Curry C.V., Challen G.A., Li W., Wheeler D., Rebel V.I., and Goodell M.A.. 2015. Dnmt3a loss predisposes murine hematopoietic stem cells to malignant transformation. Blood. 125:629–638. 10.1182/blood-2014-08-594648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahar R., Ramezani-Rad P., Mossner M., Duy C., Cerchietti L., Geng H., Dovat S., Jumaa H., Ye B.H., Melnick A., and Müschen M.. 2011. Pre-B cell receptor-mediated activation of BCL6 induces pre-B cell quiescence through transcriptional repression of MYC. Blood. 118:4174–4178. 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng D., Thakker N., Corcoran C.M., Donnai D., Perveen R., Schneider A., Hadley D.W., Tifft C., Zhang L., Wilkie A.O., et al. . 2004. Oculofaciocardiodental and Lenz microphthalmia syndromes result from distinct classes of mutations in BCOR. Nat. Genet. 36:411–416. 10.1038/ng1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntziachristos P., Tsirigos A., Van Vlierberghe P., Nedjic J., Trimarchi T., Flaherty M.S., Ferres-Marco D., da Ros V., Tang Z., Siegle J., et al. . 2012. Genetic inactivation of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Med. 18:298–303. 10.1038/nm.2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierron G., Tirode F., Lucchesi C., Reynaud S., Ballet S., Cohen-Gogo S., Perrin V., Coindre J.M., and Delattre O.. 2012. A new subtype of bone sarcoma defined by BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. Nat. Genet. 44:461–466. 10.1038/ng.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez C., Sánchez I., Demmers J.A., Rodriguez P., Strouboulis J., and Vidal M.. 2007. Proteomics analysis of Ring1B/Rnf2 interactors identifies a novel complex with the Fbxl10/Jhdm1B histone demethylase and the Bcl6 interacting corepressor. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 6:820–834. 10.1074/mcp.M600275-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki M., Kimura S., Isobe T., Yoshida K., Ueno H., Nakajima-Takagi Y., Wang C., Lin L., Kon A., Suzuki H., et al. . 2017. Recurrent PU.1 (SPI1) fusions in high-risk pediatric T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 49:1274–1281. 10.1038/ng.3900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel A., Kern W., Zenger M., Perglerová K., Schnittger S., Haferlach T., and Haferlach C.. 2016. Genetic characterization of T-PLL reveals two major biologic subgroups and JAK3 mutations as prognostic marker. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 55:82–94. 10.1002/gcc.22313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro-Ohtani Y., Wang H., Zang C., Arnett K.L., Bailis W., Ho Y., Knoechel B., Lanauze C., Louis L., Forsyth K.S., et al. . 2014. Long-range enhancer activity determines Myc sensitivity to Notch inhibitors in T cell leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:E4946–E4953. 10.1073/pnas.1407079111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T., Fukuda T., Hatano M., Koseki H., Okabe S., Ishibashi K., Kojima S., Arima M., Komuro I., Ishii G., et al. . 1999. The role of Bcl6 in mature cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 42:670–679. 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00007-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizato T., Dumitriu B., Hosokawa K., Makishima H., Yoshida K., Townsley D., Sato-Otsubo A., Sato Y., Liu D., Suzuki H., et al. . 2015. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 373:35–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Benavente C.A., McEvoy J., Flores-Otero J., Ding L., Chen X., Ulyanov A., Wu G., Wilson M., Wang J., et al. . 2012a A novel retinoblastoma therapy from genomic and epigenetic analyses. Nature. 481:329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Ding L., Holmfeldt L., Wu G., Heatley S.L., Payne-Turner D., Easton J., Chen X., Wang J., Rusch M., et al. . 2012b The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 481:157–163. 10.1038/nature10725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.