Abstract

Objective

HIV+ individuals experience an increased burden of coronary artery disease (CAD) not adequately accounted for by traditional CAD risk factors. Coronary endothelial function (CEF), a barometer of vascular health, is depressed early in atherosclerosis and predicts future events but has not been studied in HIV+ individuals. We tested whether CEF is impaired in HIV+ subjects without CAD as compared to an HIV- population matched for cardiac risk factors.

Design/Methods

In this observational study, CEF was measured noninvasively by quantifying isometric handgrip exercise (IHE)-induced changes in coronary vasoreactivity with MRI in 18 participants with HIV but no CAD (HIV+CAD-, based on prior imaging), 36 age- and cardiac risk factor-matched healthy participants with neither HIV nor CAD (HIV-CAD-), 41 subjects with no HIV but with known CAD (HIV-CAD+) and 17 subjects with both HIV and CAD (HIV+CAD+).

Results

CEF was significantly depressed in HIV+CAD- subjects as compared to that of risk-factor-matched HIV-CAD- subjects (p<0.0001), and was depressed to the level of that in HIV- participants with established CAD. Mean IL-6 levels were higher in HIV+ participants (p<0.0001), and inversely related to CEF in the HIV+ subjects (p=0.007).

Conclusions

Marked coronary endothelial dysfunction is present in HIV+ subjects without significant CAD and is as severe as that in clinical CAD patients. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction appears inversely related to the degree of inflammation in HIV+ subjects, as measured by IL-6. CEF testing in HIV+ patients may be useful for assessing cardiovascular risk and testing new CAD treatment strategies, including those targeting inflammation.

Keywords: HIV, coronary endothelial function, MRI

Introduction

HIV+ people are living longer with the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) [1,2], but are now experiencing an increasing burden of chronic diseases, including coronary artery disease (CAD) [1]. Although traditional cardiovascular risk factors are more prevalent in HIV+ populations, they do not adequately account for the increased cardiovascular risk observed in HIV+ individuals [2]. Thus the underlying mechanisms that predispose HIV+ patients to accelerated atherosclerosis and clinical events are important to identify but remain poorly characterized and understood.

Coronary endothelial function (CEF) is both an early, causal factor that contributes critically to the development of coronary atherosclerosis and a predictor of later progression to clinical events in the general population [3]. Depressed CEF responds favorably to risk factor modification, and thus CEF is often considered a barometer of vascular health [4]. Healthy endothelial cells release nitric oxide (NO) during stress, resulting in vasodilatation and increased coronary blood flow but endothelial dysfunction is associated with an impaired vasoactive response [5]. CEF was previously only assessed invasively in the catheterization laboratory by measuring changes in coronary diameter and flow in response to endothelial-dependent stressors [6]. The invasive nature of cardiac catheterization precluded CEF studies in healthy, low-risk individuals before the development of CAD and in stable CAD patients. Although systemic endothelial dysfunction was reported in HIV+ people [7], peripheral artery endothelial function correlates only modestly with CEF [8] and the latter is more closely related to underlying CAD [5,9,10].

It is not known whether CEF is depressed in HIV+ populations but CEF measures promise important biologic insights into both early and later coronary consequences of contemporary HIV infection. Recently, noninvasive measures of CEF were developed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to detect changes in coronary artery area and blood flow in response to isometric handgrip exercise (IHE), an endothelial dependent stressor [9,10]. Those MRI-IHE detected coronary responses were shown to be NO-dependent, reproducible, and thus indicative of CEF [9,10]. We exploit these new noninvasive CEF techniques here to test the hypothesis that CEF is impaired early in HIV+ populations, even before the development of CAD, as compared to age- and risk factor-matched healthy HIV- subjects. To probe the later vascular consequences of HIV, we determined whether CEF is further worsened in HIV+ patients with known CAD as compared to stable CAD patients without HIV infection.

Because chronic inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in both the general population [11] and in HIV infected subjects, we also determined whether the extent of any impairment in CEF in HIV+ people is related to the circulating levels of the inflammatory biomarkers, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) [12].

Methods

Patients

All participants provided written informed consent to a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board. Subjects had no contraindications to MRI and patients were recruited from outpatient clinics at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Four groups of subjects were recruited: 1) healthy subjects without HIV and without CAD, defined as 50 years or younger without a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes or more than one CAD risk factor, or over age 50 with an Agatston [13] coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 0 (HIV-CAD-, n=36) within the last 5 years; 2) subjects with a diagnosis of HIV without CAD defined as no significant cardiac history and a CAC score of 0 (HIV+CAD, n=18). A contrast-enhanced CT angiogram was also performed in the majority of the HIV+CAD- subjects (15/18; 83%) and demonstrated 30% or less coronary irregularities; 3) patients with known CAD (defined as presence of between 30% and 70% luminal stenosis, on prior coronary x-ray angiography) and without HIV infection (HIV-CAD+, n=41), and 4) HIV+ subjects with known CAD (HIV+CAD+, n=17). The coronary disease in both the HIV+ and HIV- groups was stable and the subjects were receiving medical management. The HIV+ participants on antiretroviral therapy (ART) were on stable therapy for at least 1 year.

MRI Study Protocol

A commercial 3.0 Tesla (T) whole-body MR scanner (Achieva, Philips, Best, NL) with a 32-element cardiac coil for signal reception was used. Detailed MR parameters were previously reported [9,10,14]. Participants underwent MRI in the morning in the fasting state (>8 hours) before the administration of any prescribed vasoactive medications. Images were taken perpendicular to a segment of a native coronary artery that had not undergone prior intervention or, if not, did not have a significant stenosis by invasive angiography. To ensure that slice orientation was perpendicular to the coronary artery, double oblique scout scanning was performed [15]. Alternating anatomical and velocity-encoded images were collected at baseline and during 4–7 minutes of continuous isometric handgrip exercise (IHE) using an MRI-compatible dynamometer (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) [16] at 30% of maximum grip strength and while being directed by a research nurse. The imaging plane for the endothelial function measurements was localized to a proximal or mid coronary arterial segment that was straight over a distance of approximately 20 mm. In cases where two coronary arteries per participant and/or different segments of the same vessel could be imaged, the results for each were quantified and averaged. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured throughout using a non-invasive and MRI-compatible ECG and calf blood pressure monitor (Invivo, Precess, Orlando, FL, USA). The rate pressure product (RPP) was calculated as systolic blood pressure x heart rate. The total duration of each MRI exam was ~ 50 minutes.

Image Analysis

Baseline and IHE stress images for coronary cross sectional area (CSA) and velocity-encoded images for flow calculation were analyzed as previously described [9,14]. Coronary flow velocity (CFV) was measured in cm/s and coronary blood flow (CBF) was calculated as previously described [10,14,17]. Segments with poor image quality (blurring due to artifact/patient motion) on either the baseline or stress exams were excluded from analysis. Both per segment and per subject analyses were performed. MRI interpretation was performed by two independent readers who were blinded to clinical and laboratory information at the time of analysis but not to HIV status.

Laboratory measurements

Venous blood samples were collected the day of the study after an overnight fast to determine the concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) in most subjects (HIV-/CAD-, N=18; HIV+/CAD-, N=16; HIV-/CAD+, N=35; HIV+/CAD+, N=12). The hsCRP sample was collected in a gel tube and measured using the turbidometry method by the Johns Hopkins Hospital main chemistry lab. IL-6 was measured with enzyme link immune assay (ELISA) by Quest laboratory. A fasting lipid panel, CD4 count and HIV and HCV (Hepatitis C virus) RNA measurements were obtained the day of the study or were available in the electronic medical records within the last 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. To compare between-group differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, lipid profiles, and other factors, non-parametric ANOVA was used for continuous variables and the Chi-square test was employed for categorical variables. Multiple linear regression model was used to examine if HIV-serostatus was independently associated with CEF. The initial multivariate regression model included all covariates. The importance of each variable included in the multivariate model was evaluated with 1) an examination of the Wald statistic for each variable in the model and 2) a comparison of each estimated regression coefficient in the multivariate model with the regression coefficient from the corresponding univariate model. Those variables that ceased to make significant contributions to the models based on these two criteria were deleted in a stage wise manner, and a new model was refitted. This process of eliminating, refitting, and verifying continued until all of the variables included were statistically significant, yielding a final model. Linear regression analysis was performed to assess correlation between inflammatory markers (hsCRP and IL-6) and each CEF parameter: area and flow change with IHE from baseline. Since laboratory and imaging measurements may include influential data, which may contain important information, robust regression model with the least trimmed squares (LTS) estimation method was used to evaluate associations between IL-6 levels and area change and between IL-6 and flow change [18]. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value<0.05, and data are presented as means. A power calculation indicated that 42 subjects in each group (HIV+ CAD- and HIV-CAD-) were needed to detect a conservative absolute difference of 3% in stress-induced CSA between HIV+CAD- and HIV-CAD- subjects (standard deviation=6% for each group for %CSA). However, after an interim analysis, we observed greater CEF differences between groups than originally anticipated that were highly statistically significant and no additional subjects were enrolled.

Results

Subject Characteristics

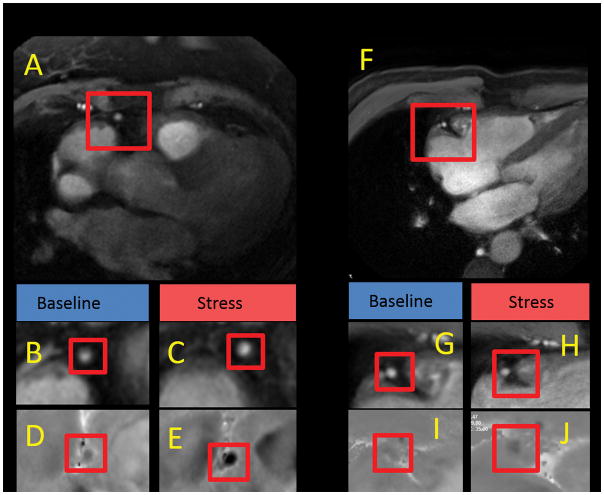

The characteristics of all study subjects are presented in Table 1. Note that ~95% of HIV+ subjects were taking ART with suppression of HIV RNA level (88% with HIV RNA <20 copies/mL) and CD4 counts > 200/mm3 (Table 1). Importantly, there was no significant difference in age, BMI, diabetes, tobacco abuse, or cardiovascular medication use between the HIV+CAD- and risk-factor matched HIV-CAD- participants (Table 1). The prevalence of hypertension trended nonsignificantly higher in the HIV+CAD- subjects than in HIV-CAD- subjects (p=0.09). All subjects completed the MRI-IHE study and there were no significant differences in mean RPP change or peak RPP during IHE among the four groups. Representative MR images, including those demonstrating changes in CSA and CBF during IHE are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristics | HIV-/CAD- (n=36) | HIV+/CAD-(n=18) | P | HIV-/CAD+ (n=41) | HIV+/CAD+(n=17) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean ± SE | 52 ± 2 | 52 ± 2 | NS | 59 ± 1 | 59 ± 1 | NS |

| Male Gender n (%) | 16 (44) | 12 (63) | NS | 35 (85) | 12 (70) | NS |

| BMI | 27 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | NS | 29 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | NS |

| PCI/Stents, n (%) | N/A | N/A | - | 21 (51) | 5 (29) | NS |

| CABG surgery, n (%) | 0 | 0 | - | 2 (4) | 1 (6) | NS |

| HTN, n | 8 (22) | 8 (44) | NS | 30 (73) | 10 (58) | NS |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 | 0 | - | 6 (15) | 1 (6) | NS |

| Smoker, n (%) | 0 | 0 | - | 7 (17) | 5 (30) | NS |

| ACE-inhibitor/ARB n (%) | 3 (8) | 5 (27) | NS | 22 (53) | 6 (35) | NS |

| Statin, n (%) | 6 (16) | 2 (11) | NS | 31(76) | 11 (65) | NS |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | NS | 26 (63) | 6 (35) | NS |

| ASA, n (%) | 9 (25) | 3 (16) | NS | 35(85) | 12 (70) | NS |

| Protease inhibitors, n (%) | N/A | 12 (60) | - | N/A | 10 (58) | - |

| HCV co-infection n (%) | 0 | 7 (39) | <0.05 | 0 | 11 (65) | <0.05 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 112 ± 6 | 93 ± 6 | NS | 77 ± 4 | 86 ± 6 | NS |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 59 ± 4 | 65 ±5 | NS | 53 ± 3 | 55 ± 4 | NS |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 93 ± 10 | 121 ± 13 | NS | 110 ± 7 | 130 ± 13 | NS |

| CD4 count (mm3) | N/A | 614 ± 93 | - | N/A | 629 ± 63 | - |

| Viral load, <20 copies/mL (%) | N/A | 15 (83) | - | N/A | 16 (95) | - |

| ART n, (%) | N/A | 17 (94) | - | N/A | 17 (100) | - |

| Coronary segments studied with MRI | 52 | 30 | 50 | 31 | ||

| LAD | 14 | 9 | 16 | 10 | ||

| RCA | 38 | 21 | 30 | 21 |

Abbreviations: ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme, ARB= angiotensin receptor blocker, ASA=aspirin, ART= antiretroviral therapy, BMI= body mass index, CABG=coronary artery bypass graft, CAD = coronary artery disease, HCV: hepatitis C virus; HDL= high density lipoprotein HTN=Hypertension, LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery, LDL= low density lipoprotein, PCI=percutaneous intervention, RCA = right coronary artery, SE = standard error

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance anatomic and flow velocity images of right coronary artery (RCA) at rest and during isometric handgrip exercise (IHE) in HIV-CAD- and HIV+CAD- subjects. A, Cross-sectional image perpendicular to the RCA (red box) is shown from an HIV-CAD- subject. Magnified cross-sectional image of the RCA at rest (B) and during IHE (C). Magnified flow velocity image of the RCA in the same subject is shown at rest (D) and during IHE (E) in diastole, wherein the signal phase is proportional to flow velocity with the darker pixels during IHE indicating higher velocity in the caudal direction through the RCA. F, Cross-sectional image perpendicular to the RCA (red box) is shown for the HIV+CAD- subject. Magnified cross-sectional image of the RCA at rest (G) and during IHE (H). Magnified flow velocity image of the RCA in the same subject is shown at rest (I) and during IHE (L) in diastole, wherein the signal darkness does not increase during IHE as it does in the healthy subject (E).

Coronary endothelial function in healthy subjects and CAD patients (HIV-)

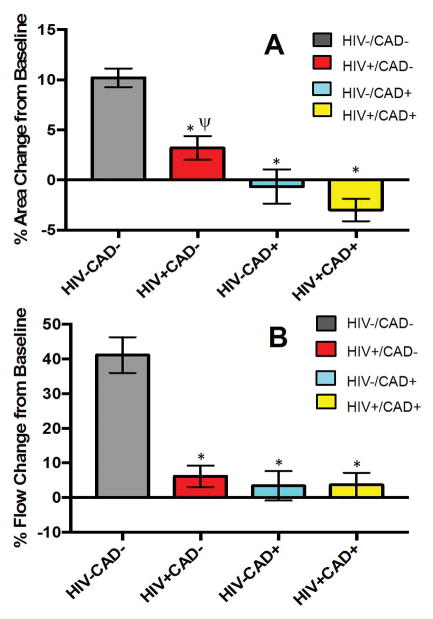

HIV-CAD- subjects exhibited coronary vasodilatation during IHE (+10.2±0.9% CSA change with IHE p<0.0001 vs. baseline) while HIV-CAD+ exhibited no significant change in CSA during IHE (−0.6±1.7% CSA change from baseline, p=NS) (Fig. 2). Likewise, there was a significant increase in mean CBF (+41.2±5.1%) in HIV-CAD- subjects with IHE but no change in the HIV-CAD+ group (+3.4±4.2% CBF change, p=NS) (Fig. 3). These observations are consistent with prior studies [10,14].

Figure 2.

(A) Summary CEF results for mean cross sectional area change (CSA) in response to IHE for healthy subjects (HIV-CAD-; gray bar, n=36), HIV+CAD- subjects (red bar, n=18), patients with CAD (HIV-CAD+; blue bar, n=41), and patients with HIV and CAD (HIV+CAD+, yellow bar, n=17). Data are shown on a per subject basis. ANOVA was used for among group comparisons (P<0.0001, data normally distributed). * p< 0.0001 vs HIV-CAD- group. ψ p< 0.001 vs HIV+CAD+ (B) Summary CEF results for the coronary blood flow (CBF) responses to IHE for healthy subjects (HIV-CAD-; gray bar, n=36), HIV+CAD- subjects (red bar, n=18), participants with CAD (HIV-CAD+; blue bar, n=41), and participants with HIV and CAD (HIV+CAD+, yellow bar, n=17). Data are shown on a per subject basis. Kruskal Wallis test was used for among group comparisons (P<0.0001, data not normally distributed). * p< 0.0001 vs HIV-CAD- group.

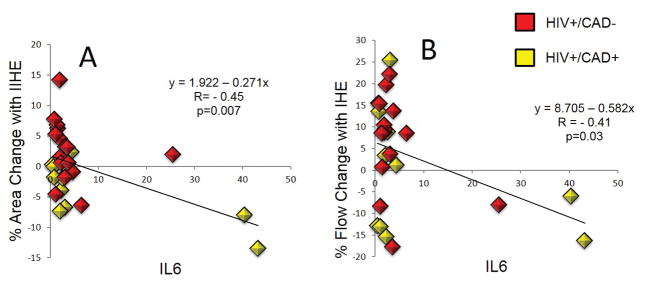

Figure 3.

(A) Summary results for high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) for healthy subjects (HIV-CAD-; gray bar, n=18), HIV+CAD- subjects (red bar, n=16), subjects with CAD (HIV-CAD+; blue bar, n=35) and subjects with HIV and CAD (HIV+CAD+, yellow bar, n=12). Data are shown on a per subject basis. Kruskal Wallis test was used for among group comparisons (P=NS, data not normally distributed).

(B) Summary results for interleukin 6 (IL-6) for healthy subjects (HIV-CAD-; gray bar, n=16), HIV+CAD- subjects (red bar, n=15), subjects with CAD (HIV-CAD+; blue bar, n=32) and subjects with HIV and CAD (HIV+CAD+, yellow bar, n=11). Data are shown on a per subject basis. Kruskal Wallis test was used for among group comparisons (P<0.001, data not normally distributed). * p<0.001 vs HIV-CAD- group; † p<0.05 vs HIV-CAD- group.

Coronary endothelial function in HIV+ subjects without CAD

To determine whether CEF is impaired in HIV+ individuals early, in the absence of CAD, we compared CEF in HIV+CAD- individuals with that of HIV-CAD-. Coronary arteries in HIV+CAD- subjects minimally vasodilated with IHE (+3.2±1.2% mean CSA change with IHE p=NS vs. baseline) and the degree of vasodilation with IHE was significantly impaired as compared to that of HIV-CAD-, (+10.2±0.9% mean CSA change with IHE, p<0.0001, Fig. 2A). The abnormal CSA response of HIV+CAD- subjects was not significantly different than that of the HIV-CAD+ subjects (−0.6±1.7% CSA change from baseline p=NS, Fig. 2A). There was no significant increase in CBF during IHE in HIV+CAD- patients. The CBF response of HIV+CAD- subjects (+6.2±3.0% CBF change from baseline) was significantly less than that of controls (41.2±5.1% CBF increase from baseline, p<0.0001) but not different than that of patients with clinical CAD (3.4±4.2% CBF change, p=NS, Fig. 2B.

To determine whether the significant coronary endothelial dysfunction observed in the HIV+ CAD- subjects was related to co-infection with HCV, we performed additional analyses on the subset of HIV+CAD- subjects who were HCV- (n=11) and on the subset of HIV+CAD- subjects who were either HCV- or who were HCV treated and cured (total n=15). The mean change in %CSA and CBF in these two groups (HIV+CAD-HCV- and HIV+CAD+HCVc, Supplemental Figs 1–4) was similar to that of the overall HIV+CAD- subjects (Main Figure 2) and significantly depressed compared to that of the healthy subjects. Thus the significantly depressed CEF observed in HIV+CAD- subjects was not attributable to concurrent HCV infection.

On multivariate analysis when data were adjusted for age, BMI, gender, race, hypertension, and active hepatitis C infection, the IHE-induced changes in CSA (p=0.01) and in CBF (p<0.001) were still significantly reduced in HIV+CAD- subjects as compared to those of HIV-CAD- subjects. Thus HIV+ patients with no significant CAD have severely impaired CEF that is similar to that of HIV- patients with established CAD.

Coronary endothelial function in HIV+ patients with established CAD

To determine whether CEF is further impaired in HIV+ individuals who have developed clinical CAD, we compared CEF in HIV+CAD+ individuals with that of HIV-CAD+ individuals. Coronary arteries of HIV+CAD+ individuals significantly vasoconstricted in response to IHE (−3.0±1.1% mean CSA change from baseline p=0.03) while those of the HIV-CAD+ group exhibited no significant change from baseline with IHE (−0.6±1.7% mean CSA change from baseline, p=NS). Likewise, CBF did not change significantly with IHE in either HIV+CAD+ subjects (+3.6±3.5 % CSA change from baseline, p=NS) or HIV-CAD+ patients (+3.4±4.2% CSA change from baseline, p=NS; Fig. 2). Thus, although CEF was significantly impaired in HIV+ people before the development of CAD (HIV+CAD- vs HIV-CAD-), CEF does not seem to be further impaired in HIV+ people with CAD as compared to that in HIV- people with clinical CAD.

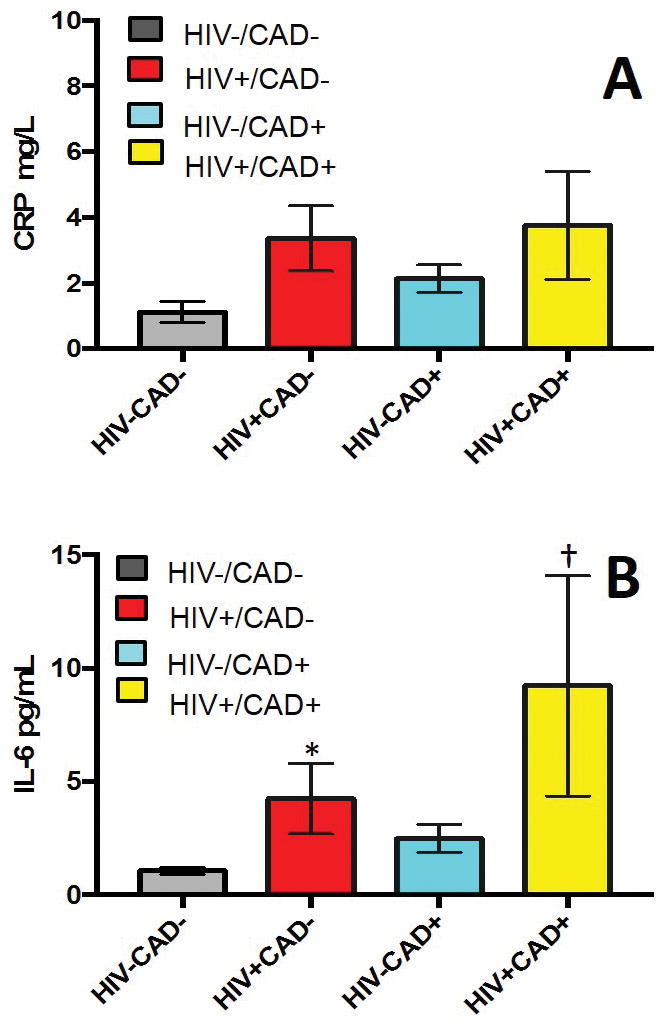

Inflammatory parameters and coronary endothelial function

To determine whether the extent of CEF impairment in HIV+ participants is related to systemic inflammation, hsCRP and IL-6 were measured and compared to each CEF parameter. Although mean hsCRP levels did not differ among the four groups (Fig. 3A), IL-6 levels did significantly differ (p<0.001) with significantly higher levels in HIV+CAD- than in HIV-CAD- individuals (p<0.001) (Fig. 3B). IL-6 levels were not different between HIV-CAD- and HIV-CAD+ individuals (Fig. 3B). Importantly, IL-6 levels in HIV+ individuals were significantly inversely related to CEF, as measured by mean %CSA and %CBF changes with IHE (Fig. 4). The correlation was still significant after correction with a robust regression analysis in consideration of possible influential data (p=0.007 for IL-6 vs. %CSA and p=0.03 for IL-6 vs. %CBF). However, when removing the 3 outliers from the 27 subjects this correlation became non-significant.

Figure 4.

Relationship between interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels and CEF. (A) Significant inverse relationship between IL-6 levels and %CSA change of coronary vessels in response to IHE. (B) Significant inverse relationship between IL-6 level and % CBF change in response to IHE in HIV+ subjects. Red squares represent HIV+CAD- (n=15) and yellow squares represent HIV+CAD+ (n=11) subjects. The strong correlation was still highly significant after correction with a robust regression analysis in consideration of possible influential data.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that HIV+ participants, even in the absence of overt coronary artery disease and coronary artery calcification, have significant coronary endothelial dysfunction that is as severe as that in HIV- subjects with established clinical CAD. Although HIV+ participants with CAD exhibit severely depressed CEF, as expected, it is not more severely depressed than that in CAD patients who are HIV-. The depressed CEF in HIV+ subjects may be related to an augmented inflammatory pattern, as measured by IL6, despite chronically suppressed HIV RNA levels and sufficient CD4 counts (Table 1).

Coronary endothelial function in HIV- healthy subjects and CAD patients

Coronary endothelial dysfunction is a well-known independent predictor of cardiovascular events, and a potential target for medical interventions in HIV- populations [3]. We used a non-invasive, reproducible MRI method to measure NO-mediated coronary endothelial function [9,10,17] that allows studies in healthy and low-risk populations and for repeated studies, unlike prior catheterization-based measures. In the present study, healthy subjects without HIV infection (HIV-CAD-) exhibited coronary vasodilatation and an increase in CBF during IHE while patients with CAD (HIV-CAD+) exhibited no significant change in CSA and CBF during IHE, consistent with prior studies [10,14].

Coronary endothelial function in HIV+ subjects without overt CAD

To our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate that HIV+ individuals on contemporary suppressive antiretroviral therapy and no significant coronary atherosclerosis have profoundly worse coronary endothelial function compared to a matched HIV- population (Figs 2–3). Although prior studies reported the presence of peripheral endothelial dysfunction in HIV+ populations [19,20], peripheral artery endothelial function correlates only modestly with CEF [8] and the latter is more closely related to underlying local CAD [3]. Myocardial perfusion in HIV+ subjects was evaluated with positron emission tomography (PET) in two prior studies but neither demonstrated abnormal coronary endothelial function. One study using dipyridamole stress that induces maximal vasodilatation but is not purely an endothelial-dependent stressor, reported no difference between HIV+ subjects and a control group [21]. Another PET study measured myocardial perfusion in HIV+ people during cold pressor testing, an arguably more endothelial-dependent stressor than dipyridamole, but the study had no HIV- subjects for comparison [22] and the cold pressor perfusion results in HIV+ subjects were similar to those previously reported in healthy subjects [23]. The MRI techniques used here offer direct measures of coronary artery area and blood flow changes in response to a demonstrated NO-dependent endothelial stressor [9].

The presence of coronary endothelial dysfunction observed here in HIV+ people may explain in part why HIV+ individuals are at increased risk for cardiovascular events despite a suppressed HIV RNA level [24], even in the absence of overt coronary atherosclerosis. In HIV- populations, abnormal CEF is associated with an approximately 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events [3]. Likewise, the relative risk of cardiovascular events is increased a similar amount (~1.75) in HIV+ compared to an HIV- matched population [2]. Therefore, this degree of observed coronary endothelial dysfunction in HIV+ subjects is sufficiently large, in theory, to account for much of the increased cardiovascular risk in this population. All of our HIV+CAD- study participants previously underwent imaging studies that indicated no calcified CAD and most (83%) underwent angiography, all demonstrating no stenosis. Thus these findings demonstrate that coronary endothelial dysfunction is present even in the absence of luminal stenosis and calcified coronaries, and raise the question of whether further risk characterization may be needed in the HIV+ population.

To determine the degree of coronary endothelial dysfunction in HIV+ participants with clinical CAD, we compared CEF in HIV+CAD+ individuals to that of CAD patients who were HIV-. The HIV+CAD+ subjects significantly vasoconstricted in response to IHE and the degree of their endothelial dysfunction did not significantly differ from that of the HIV-CAD+ patients. These findings are notable in light of the fact that the HIV+ group was medically optimized with ART with a fully suppressed HIV RNA and suggests that once clinical coronary artery disease develops, coronary endothelial function does not significantly further worsen with HIV infection.

Correlation between inflammatory parameters and coronary endothelial dysfunction

Increased systemic inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease in HIV+ subjects [12]. Although hsCRP did not significantly differ among the groups, IL-6 was significantly increased in HIV+CAD- compared to HIV-CAD- subjects. Moreover, there was an inverse relationship between IL-6 and CEF, indicating that an increased level of inflammation as measured by IL-6 is associated with impaired CEF. Prior studies report that plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 are increased in HIV+ individuals [25,26] and persist during HIV infection, even in patients with low residual viremia (viral load ≤20 copies/ml) [27,28]. Higher levels of IL-6 strongly predict cardiovascular events in ART-treated and ART-naive HIV + subjects [29,30]. Interestingly, IL-6 is reported to be more predictive of adverse cardiovascular events than the inflammatory marker hsCRP in HIV+ subjects [13,30]. Of note, in our study when removing from this analysis the 3 potential outliers, the correlation was no longer significant (r=−0.27). A larger study could better determine whether the observed relationship between inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in HIV+ people is robust.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study and thus it is difficult to determine whether the significant abnormalities in CEF observed in HIV+ participants on contemporary therapy are due to HIV infection, ART, or something else. It should be emphasized, however, that the groups were well matched in terms of age, tobacco use, hypertension and diabetes. In addition, on multivariate analysis, none of the known confounders including HTN and HCV status accounted for the differences in CEF between the HIV+ group and the control group. Although we noted that the HIV+CAD- group had endothelial dysfunction to a degree similar to that of the HIV- subjects with known CAD, most of the CAD subjects were on statin therapy which may have attenuated the decline in CEF that would otherwise have been observed in the CAD group. Regardless, the main observation of this study, is that CEF is significantly impaired in HIV+CAD-, subjects as compared to HIV-CAD- subjects, and these two groups are well matched in terms of conventional cardiovascular medications and risk factors. The sample size may not afford sufficient power to detect a modest correlation between hsCRP levels and endothelial dysfunction. However, the sample size was sufficient to detect an inverse relationship between IL-6 and coronary endothelial function in HIV+ participants. The latter relationship may be influenced by a few subjects and merits additional studies in larger populations. Another limitation is that the MRI analysis was not performed blinded in terms of HIV status. However, in a subset of HIV-CAD- and HIV+CAD- subjects, repeated blinded analysis yielded similar results (data not shown). Other markers, such as ones of monocyte activation sCD163 or sCD14 have not been tested in our study population and have been associated with endothelial dysfunction and CAD risk factors in other studies [30]. Likewise, additional studies would be required to determine whether other factors such as HIV duration, immune factors, or type of ART may affect CEF and cardiovascular risk.

Conclusions

In summary, coronary endothelial dysfunction is present in HIV+ people with no overt coronary artery disease and the degree of dysfunction is similar to that of patients with established clinical coronary artery disease. The mechanism of endothelial dysfunction may be partly related to increased systemic inflammation even in the presence of adequately treated HIV infection. Our findings suggest the possibility that non-invasive measurement of CEF with MRI may complement risk assessment in HIV+ patients even in the absence of significant CAD and may provide a valuable tool to probe new treatment approaches aimed at targeting the earliest stages of coronary disease in HIV+ populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: Work supported by NHLBI grants HL120905 and HL125059, and CFAR (Center for AIDS Research at Johns Hopkins).

Footnotes

Roles of authors:

MI, MS, TB, RM, GG RWG and AGH contributed to design of study. TB, RM, PBC, MI, GG, RGW and AH recruited subjects. MI, AGH, MS and SS contributed to acquiring and/or analysis of data. MI, MS, SS, SL, GG, TB, RM, RGW and AGH contributed to interpretation of data. All authors contributed to drafting and/or editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Boccara F, Lang S, Meuleman C, Ederhy S, Mary-Krause M, Costagliola D, et al. HIV and coronary heart disease: time for a better understanding. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:511–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:2506–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schachinger V, Britten MB, Zeiher AM. Prognostic impact of coronary vasodilator dysfunction on adverse long-term outcome of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:1899–906. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vita JA, Keaney JF., Jr Endothelial function: a barometer for cardiovascular risk? Circulation. 2002;106:640–2. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028581.07992.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iantorno M, Weiss RG. Using advanced noninvasive imaging techniques to probe the links between regional coronary artery endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2014;24:149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludmer PL, Selwyn AP, Shook TL, Wayne RR, Mudge GH, Alexander RW, et al. Paradoxical vasoconstriction induced by acetylcholine in atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1046–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198610233151702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrade AC, Ladeia AM, Netto EM, Mascarenhas A, Cotter B, Benson CA, Bandaro R. Cross-sectional study of endothelial function in HIV-infected patients in Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:27–33. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD, Meredith IT, Knab S, Delagrange D, et al. Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1235–41. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hays AG, Iantorno M, Soleimanifard S, Steinberg A, Schar M, Stuber M, et al. Coronary vasomotor responses to isometric handgrip exercise are primarily mediated by nitric oxide: a noninvasive MRI test of coronary endothelial function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H1343–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00023.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hays AG, Hirsch GA, Kelle S, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG, Stuber M. Noninvasive visualization of coronary artery endothelial function in healthy subjects and in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1657–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordell AD, McKenna M, Borges AH, Duprez D, Neuhaus J, Neaton JD. Severity of cardiovascular disease outcomes among patients with HIV is related to markers of inflammation and coagulation. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e000844. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hays AG, Kelle S, Hirsch GA, Soleimanifard S, Yu J, Agarwal HK, et al. Regional coronary endothelial function is closely related to local early coronary atherosclerosis in patients with mild coronary artery disease: pilot study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:341–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.969691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuber M, Botnar RM, Danias PG, Sodickson DK, Kissinger KV, Van Cauteran M, et al. Double-oblique free-breathing high resolution three-dimensional coronary magnetic resonance angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:524–31. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss RG, Bottomley PA, Hardy CJ, Gerstenblith G. Regional myocardial metabolism of high-energy phosphates during isometric exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays AG, Stuber M, Hirsch GA, Yu J, Schar M, Weiss RG, et al. Non-invasive detection of coronary endothelial response to sequential handgrip exercise in coronary artery disease patients and healthy adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rousseeuw PJ, Leroy AM. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torriani FJ, Komarow L, Parker RA, Cotter BR, Currier JS, Dube MP, et al. Endothelial function in human immunodeficiency virus-infected antiretroviral-naive subjects before and after starting potent antiretroviral therapy: The ACTG (AIDS Clinical Trials Group) Study 5152s. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solages A, Vita JA, Thornton DJ, Murray J, Heeren T, Craven DE, Horsburgh Endothelial function in HIV-infected persons. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;42:1325–32. doi: 10.1086/503261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebech AM, Kristoffersen US, Wiinberg N, Kofoed K, Andersen O, Hesse B, et al. Coronary and peripheral endothelial function in HIV patients studied with positron emission tomography and flow-mediated dilation: relation to hypercholesterolemia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2049–58. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0846-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristoffersen US, Wiinberg N, Petersen CL, Gerstoft J, Gutte H, Lebech AM, Kjaer A. Reduction in coronary and peripheral vasomotor function in patients with HIV after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study with positron emission tomography and flow-mediated dilation. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:874–80. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32833d82e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kjaer A, Meyer C, Nielsen FS, Parving H, Hesse B. Dipyridamole, Cold Pressor Test, and Demonstration of Endothelial Dysfunction: A PET Study of Myocardial Perfusion in Diabetes. J Nucl Med. 2003 Jan;44(1):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dube MP, Shen C, Mather KJ, Waltz J, Greenwald M, Gupta SK. Relationship of body composition, metabolic status, antiretroviral use, and HIV disease factors to endothelial dysfunction in HIV-infected subjects. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:847–54. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kedzierska K, Crowe SM. Cytokines and HIV-1: interactions and clinical implications. Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy. 2001;12:133–50. doi: 10.1177/095632020101200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lafeuillade A, Poizot-Martin I, Quilichini R, Gastaut JA, Kaplanski S, Farnarier C, et al. Increased interleukin-6 production is associated with disease progression in HIV infection. AIDS. 1991;5:1139–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199109000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostrowski SR, Katzenstein TL, Pedersen BK, Gerstoft J, Ullum H. Residual viraemia in HIV-1-infected patients with plasma viral load <or copies/ml is associated with increased blood levels of soluble immune activation markers. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2008;68:652–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, De Wit S, Drummond F, Lane HC, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borges AH, O’Connor JL, Phillips AN, Neaton JDm, Grund B, Neuhaus J, et al. IL-6 is a stronger predictor of clinical events than hsCRP or D-dimer during HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:408–416. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grund B, Baker JV, Deeks SG, Wolfson J, Wentworth D, Cozzi-Lepri A, et al. Relevance of Interleukin-6 and D-Dimer for Serious Non-AIDS Morbidity and Death among HIV-Positive Adults on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. PloS One. 2016;11:e0155100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Wijk JP, de Koning EJ, Cabezas MC, Joven J, op’t Roodt J, Rabelink TJ, Hoepelman AM. Functional and structural markers of atherosclerosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.