Abstract

Background

Little is known about the size and characteristics of the decision support networks of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer and whether their involvement improves breast cancer treatment decisions.

Methods

A population-based sample of patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014–15 as reported to the Georgia and Los Angeles SEER registries were surveyed approximately 7 months after diagnosis (N = 2,502, 68% response rate). Network size was estimated by asking women to list up to 3 of the most important decision support people (DSP) who helped them with locoregional therapy decisions. Decision deliberation was measured using 4-items assessing degree to which patients thought through the decision, with higher scores reflecting more deliberative breast cancer treatment decisions. We compared the size of the network (0–3 or more) across patient-level characteristics and estimated the adjusted mean deliberation scores across levels of network size using multivariable linear regression.

Results

Of the 2,502 women included in this analysis, 51% reported having 3 or more DSPs, 20% reported 2, 18% reported 1, and 11% reported not having any DSPs. Married/partnered women, those younger than 45 years old, and black women were all more likely to report larger network sizes (all p<0.001). Larger support networks were associated with more deliberative surgical treatment decisions (p <0.001).

Conclusions

Most women engaged multiple DSPs in their treatment decision making, and involving more DSPs was associated with more deliberative treatment decisions. Future initiatives to improve treatment decision making among breast cancer patients should acknowledge and engage informal DSPs.

Keywords: Breast cancer, informal decision support, decision support networks, breast cancer study, treatment decision making, caregivers, family

INTRODUCTION

Patient centered care supports engaging patients to make decisions that are both informed and values/preference-concordant. This can be challenging in breast cancer because of the complexity and number of decisions faced by newly diagnosed patients. To help facilitate decision making, women often seek guidance from multiple source, including family and friends.1–6 While many studies have examined the role family and friends play in caring for patients with cancer,7–9 there is surprisingly little research on the contribution of informal supporters to the decision-making process specifically. Indeed, most women diagnosed with breast cancer have an informal support person in the room with them during the first encounter with a surgeon. Our prior work suggests that partners positively appraised their participation in these treatment decisions,10 and a recent study found both patients and caregivers felt family involvement was helpful in their cancer treatment decision making.11 But, who patients involve in these decisions, the extent to which they are involved and whether or not their participation influences the quality of these treatment decisions remains largely unknown.

In addition, very little is known about the decision support networks themselves and how they may vary for different patient groups. For instance, prior research suggests that the involvement and influence of informal decision support persons (DSPs) may vary by race/ethnicity,3, 10 but much of the research has been limited by small sample sizes with insufficient racial/ethnic diversity, and by the inclusion of only spouses/partners.4–6 While clinicians have long been recommending that patients bring someone with them to their appointments, clinicians may benefit from a better understanding of the size and characteristics of the networks that patients rely on during their decision making. Such understanding may help clinicians to better incorporate DSPs into treatment discussions and would help guide the development of decision tools that include patients’ informal DSPs, with the goal of improving patient-centered care. In particular, establishing whether informal decision support networks contribute to greater deliberation over treatment options would allow clinicians to provide more evidence based recommendations that patients utilize their network of informal supporters when making their breast cancer treatment decisions.

To fill this gap in research on the process of breast cancer treatment decision making, we conducted a study to characterize the size and variation of informal decision support networks for women newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. We further sought to determine whether network size was associated with patient characteristics, and patients’ appraisal of their decision making process.

METHODS

Study population

The Individualized Cancer Care (iCanCare) Study is a large, population-based survey study of women with breast cancer. We identified and accrued 3930 women, ages 20–79 with newly diagnosed, early-stage breast cancer (stages 0-II) as reported to the SEER registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County in 2014–2015. Patients were ineligible if they had stage III or IV disease, had tumors larger than 5cm, or could not complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish (N= 258). Of the remaining 3,672 eligible women who were mailed surveys, 2,502 completed the survey (68% response rate) and are included in this analysis.

Patients were identified via rapid case ascertainment from surgical pathology reports. Surveys were mailed approximately 2 months after surgery (median time from diagnosis to survey completion was 7 months). We provided a $20 cash incentive and, as done in prior work,12–14 used a modified Dillman approach to encourage patient recruitment.15 This approach allows for a flexible mode of respondent follow-up, which included post-card reminders and phone reminders with the option to complete the survey during a phone interview in either Spanish or English. All materials were sent in English and Spanish to those with Spanish surnames.3, 13 Survey responses were then merged with clinical data provided by the SEER registries. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and the state and institutional IRBs of the SEER registries.

Measures

Questionnaire content was developed based on a conceptual framework which hypothesized variability in the size and influence of decision support networks across patient-level characteristics.1–3 We utilized standard techniques to assess content validity, including expert reviews, cognitive pretesting, and pilot studies in selected clinic populations. Respondents were queried about the number, influence and importance of decision support persons using adapted measures developed and validated to identify disease management supports for patients with chronic diseases.16, 17 (See Supplementary Material for measures.)

Measuring decision support networks

To our knowledge, this is the first study to ask patients to report about specific individuals involved in their cancer treatment decision making. We employed a unique methodology where patients were asked: (1) to indicate up to three specific decision support individuals (using initials only to avoid identification), (2) to indicate each person’s relationship to them (e.g., partner, daughter, friend), and (3) to rate the importance of, and satisfaction with, each person’s involvement in treatment decision making.

Size of decision support network

The decision support network size was determined by assessing the number of individuals indicated by each patient, ranging from 0 to 3 or more. While rare (n=256, 10.2%), respondents who did not answer the decision support questions entirely were categorized as having a decision support network size of zero. This categorization was based on prior work and responses to other questions that services to support the justification that patients likely did not answer because they did not have a person to name. However, to confirm our findings, we also performed the analyses with these respondents excluded, which yielded very similar results.

Patient satisfaction with and importance of DSPs

For each individual listed, respondents reported on how important the opinion of each DSP was in treatment decision making, and how satisfied they were with the level of involvement (each on 5 pt. scale from “not at all” to “very”). Overall mean scores (across all DSPs reported by each patient) were then estimated for both importance and satisfaction and categorized into high (score of 4 or greater) vs. low/moderate (score less than 4). We chose this cut off based on prior research (Hawley JCNI, Lillie) and our desire to assess the highest levels of patient-reported involvement and satisfaction.

Patient-reported network involvement

As we have done in prior studies (Hawley JNCI, Janz Supportive Cancer Care), respondents were also asked how often their DSP(s) attended their appointments, took notes during appointments, talked to them about their treatment options, and shared information with them from other sources about their treatment options (5 pt. scales from “not at all” to “often”). Overall mean scores were then estimated for each item and categorized into often/always (score of 4 or greater) vs. never/rarely (score less than 4).

Patient appraisal of decision making

We employed a measure of “treatment decision deliberation”, using a 5-item scale derived from measures of public deliberation adapted for cancer treatment-related decisions.18–20 Items assessed the extent to which a patient weighed the pros and cons, talked to other family members and friends, talked to other breast cancer patients, thought through, and spent time thinking about the decision (on 5-pt Likert-type scales from “not at all” to “very much”). An overall deliberation score was created using the mean of the responses to the five items (range 1–5) (Cronbach alpha =0.85), with higher scores representing more deliberation.

Patient Characteristics

Survey items assessed demographics including age, educational attainment (high school graduate or less, some college or college degree or more), insurance status (private, Medicaid/Medicare/VA, or none/missing), and number of comorbid health conditions (0, 1 or more). Level of acculturation among Latinas was assessed using the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH), as done in our prior studies.21 We also asked patients to report their treatment, as done in prior work,12 including primary surgical treatment modality (lumpectomy, unilateral mastectomy, bilateral mastectomy), receipt of chemotherapy (yes/no) and endocrine therapy (yes/no). Breast cancer stage (0, I, II) was obtained from the SEER record.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses incorporated weights to account for differential probabilities of sample selection across patient subgroups and non-response. Weighting assures that sample distributions resemble those of the target population and reduces the potential bias due to non-response.22 The overall distributions of network characteristics (size, relationship), DSP involvement, and patient-reported satisfaction with and influence of the DSP were estimated. The distributions of network size across levels of patient demographic and clinical characteristics were compared using Rao-scott Chi-square tests. Because of the anticipated inherent association between network size and marital status, we then estimated the associations between patient factors (age, race/acculturation) and network size, stratified by marital status and compared them using Rao-scott Chi-square tests. Multivariable linear regression was used to estimate the adjusted mean deliberation scores for each level of network size, adjusting for age, race/acculturation, insurance, partner status, comorbidity, surgical treatment and stage. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC), used two-sided tests, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Network Size

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample of 2,502 women both overall and by level of informal decision support network size. More than half of the women (51%) listed three DSPs during their treatment decision making, 20% listed two people, 19% listed one person and 10% had a network size of zero. Network size decreased with increasing age (p<0.001). Variation in network size also existed across race/acculturation (p<0.001). Both African American and Latina women reported larger network sizes compared to white women, as 58.3% of African American women and 52.3% and 56.4% of high and low acculturated Latina women reported a network size of 3 or more, compared to 48% of white women (p<0.001). As expected, marital status was positively associated with network size: Among women who were partnered/married, 51.6% reported a network size of 3 or greater compared to 49.3% of women who were not married or partnered (p<0.001). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Distribution (weighted %) of demographic and clinical characteristics by decision supporter network size

| Decision Supporter Network Size (weighted %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Patient-level Factors | Overall N=2502 |

0 N=256 |

1 N=460 |

2 N=501 |

3 N=1285 |

p-value* |

|

| ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| <45 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 14.9 | 20.9 | 60.9 | 0.001 |

| 45–54 | 20.4 | 10.7 | 16.9 | 21.9 | 50.6 | |

| 55–64 | 31.3 | 8.5 | 20.3 | 18.2 | 53.0 | |

| >65 | 40.1 | 12.5 | 19.8 | 20.9 | 46.9 | |

|

| ||||||

| Race/acculturation | ||||||

| White | 54.2 | 9.5 | 21.4 | 21.0 | 48.0 | <0.001 |

| Black | 18.0 | 9.4 | 15.3 | 17.0 | 58.3 | |

| Latina, high acculturation | 7.9 | 12.8 | 14.9 | 19.9 | 52.4 | |

| Latina, low acculturation | 7.7 | 10.2 | 15.0 | 18.4 | 56.4 | |

| Asian | 9.8 | 9.2 | 19.1 | 24.5 | 47.2 | |

| Other/unknown/missing | 2.5 | 25.0 | 15.5 | 17.8 | 41.6 | |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| High school graduate or less | 29.9 | 10.7 | 18.0 | 18.6 | 52.8 | 0.26 |

| Some College | 29.8 | 8.6 | 18.2 | 20.3 | 52.8 | |

| College graduate or more | 40.3 | 9.3 | 20.8 | 21.9 | 48.0 | |

|

| ||||||

| Insurance | ||||||

| None or Missing | 20.2 | 15.7 | 14.1 | 16.8 | 53.4 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid, Medicare or VA | 35.2 | 9.7 | 18.6 | 21.0 | 50.7 | |

| Private or Other | 44.6 | 8.0 | 21.5 | 21.2 | 49.4 | |

|

| ||||||

| Partner/marital status | ||||||

| Not partnered/Married | 38.9 | 15.5 | 15.9 | 19.3 | 49.3 | <.0001 |

| Partnered/Married | 61.0 | 6.2 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 51.6 | |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| 0 | 67.8 | 10.4 | 19.8 | 20.6 | 49.2 | 0.24 |

| 1+ | 32.2 | 9.6 | 17.1 | 19.6 | 56.7 | |

|

| ||||||

| SEER Stage | ||||||

| 0 | 24.9 | 11.7 | 20.4 | 18.6 | 49.3 | 0.26 |

| I | 50.1 | 9.3 | 19.7 | 20.2 | 50.8 | |

| II | 24.0 | 10.8 | 15.5 | 21.4 | 52.4 | |

|

| ||||||

| Surgical Treatment | ||||||

| Lumpectomy | 64.6 | 10.5 | 20.4 | 19.9 | 49.1 | 0.11 |

| Unilateral Mastectomy | 17.4 | 9.3 | 14.9 | 19.9 | 55.9 | |

| Bilateral Mastectomy | 18.0 | 8.1 | 17.5 | 21.1 | 53.3 | |

P-values from Rao-Scott chi-square tests for association

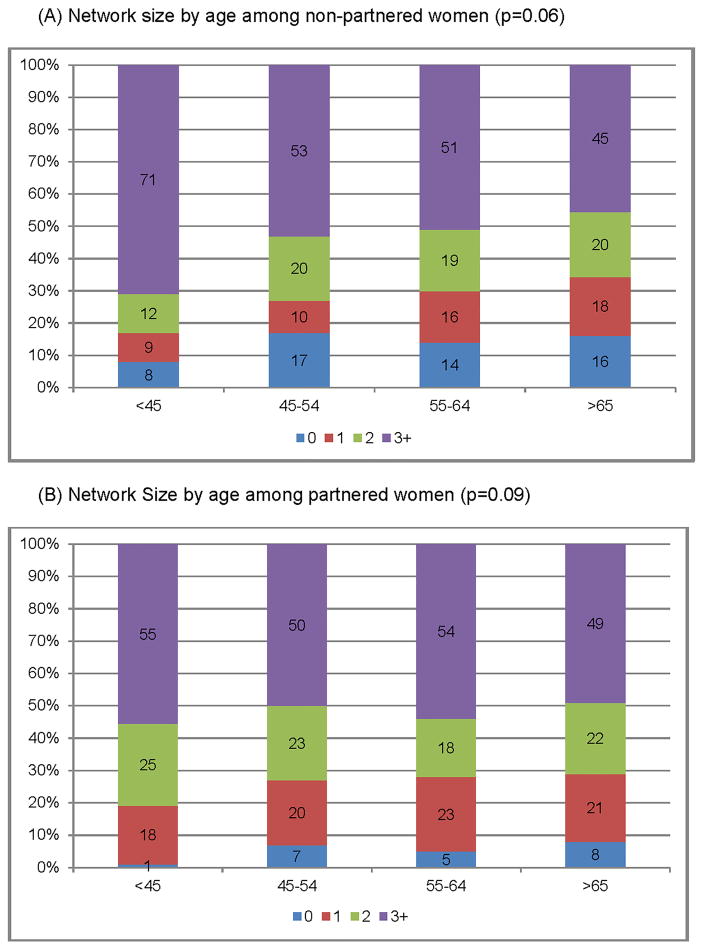

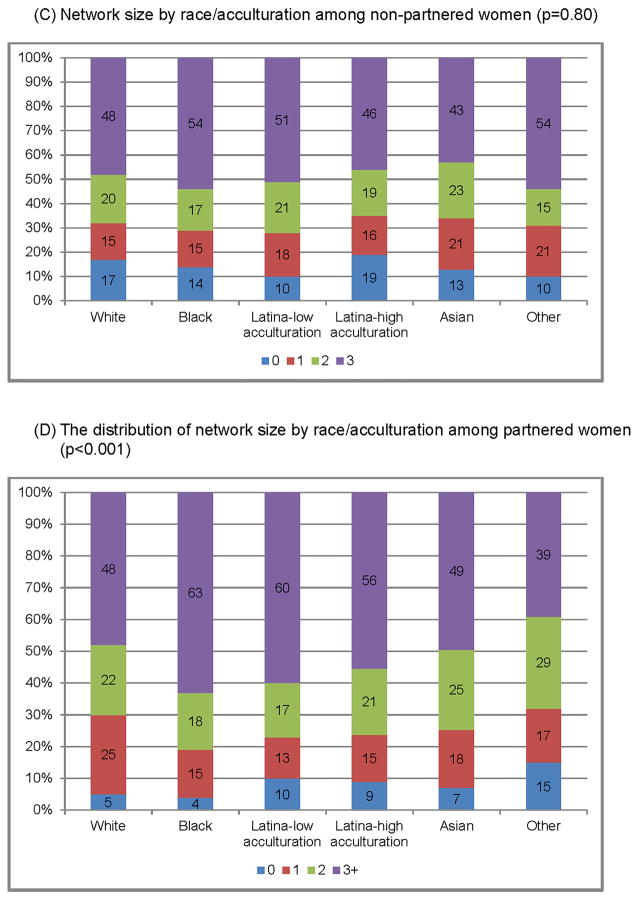

Figure 1 displays the size of the decision support network across age and race, stratified by partner status. Very little heterogeneity was seen in the association between age and network size across partner status. Among both partnered and not partnered women, a greater proportion of younger women reported a larger network size compared to older women, albeit these associations did not reach statistical significance (not partnered p=0.06; partnered p=0.10) (Figures 1A–B).

Figure 1.

Distribution of network size by age (A/B), race (C/D), stratified by partner status

Figure 1A: Network size by age among non-partnered women (p=0.06)

Figure 1B: Network Size by age among partnered women (p=0.09)

Figure 1C: Network size by race/acculturation among non-partnered women (p=0.80)

Figure 1D: The distribution of network size by race/acculturation among partnered women (p<0.001)

The association between race/acculturation and network size varied noticeably across partner status. Among women who were partnered, race/acculturation was significantly associated with network size (p<0.001), as 63% of black women, 56% of high and 60% of low acculturated Latina women and 48% of white women reported a network size of 3 or more, (Figure 1D). This association, however, was mitigated among women who were not partnered (p=0.80). (Figure 1C)

Characteristics of Networks

Table 2 displays the distributions of the size, relationship and involvement of the decision support networks both overall and stratified by marital status. Of the DSPs that the respondents identified, overall most (31.2%) were children, followed by partners/spouses (21.2%), 18.8% friends/other (18.8%), siblings (11.3%), other family members (7.4%), and parents (6.1%). Partnered/married women most often reported their partner as their main DSP (37.9%), whereas not partnered/unmarried women most often reported children as their main DSP (38.4%). In addition, women who were not partnered or married more often reported siblings as their DSP (15.5%) or friends (22.3%) as compared to partnered/married women (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Network Characteristics and DSP Involvement in Treatment Decision Making (N=2502), stratified by Partner Status

| Network Characteristics | Overall N=2502* |

Not Partnered N=961 |

Partnered N=1496 |

p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| weighted % | weighted % | weighted % | ||

|

| ||||

| Network Size (n=2457) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 9.8 | 15.5 | 6.2 | |

| 1 | 19.0 | 15.9 | 21.1 | |

| 2 | 20.5 | 19.3 | 21.2 | |

| 3+ | 50.7 | 49.3 | 51.6 | |

|

| ||||

| DSP Relationship to Patient** | <0.001 | |||

| Partner/Spouse | 21.2 | 2.3 | 37.9 | |

| Children | 31.2 | 38.4 | 27.0 | |

| Siblings | 11.3 | 15.5 | 8.0 | |

| Parent | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.5 | |

| Other Family Members | 7.4 | 11.0 | 4.6 | |

| Friends/Other | 18.8 | 22.3 | 13.5 | |

| Multiple | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.6 | |

|

| ||||

| DSP Involvement | ||||

|

| ||||

| Attended Appointments (n=2394) | <0.001 | |||

| Never/rarely/often | 26.7 | 37.7 | 19.8 | |

| Very Often/always | 73.3 | 62.3 | 80.2 | |

|

| ||||

| Took Notes during Appointments (n=2377) | 0.076 | |||

| Never/rarely/often | 49.5 | 51.9 | 47.9 | |

| Very Often/always | 50.5 | 48.1 | 52.1 | |

|

| ||||

| Talked with them about Treatment (n=2364) Options | <0.001 | |||

| Never/rarely/often | 25.8 | 32.9 | 21.3 | |

| Very Often/always | 74.2 | 67.1 | 78.7 | |

|

| ||||

| Shared information about treatment from other sources (n=2380) | 0.49 | |||

| Never/rarely/often | 43.2 | 44.1 | 42.6 | |

| Very Often/always | 56.8 | 55.9 | 57.4 | |

|

| ||||

| Patient-reported DSP Measures | ||||

|

| ||||

| Patient-reported Satisfaction with DSP (n=2457) | <0.001 | |||

| Low/Moderate (<4) | 23.5 | 30.4 | 19.0 | |

| High (≥4) | 76.5 | 69.6 | 81.0 | |

|

| ||||

| Patient-reported DSP Importance (n=2457) | <0.001 | |||

| Low/Moderate (<4) | 31.4 | 38.7 | 26.8 | |

| High (≥4) | 68.6 | 61.3 | 73.2 | |

N is unweighted and does not add up to 2502 due to missingness.

Relationships were categorized for all reported DSPs for each patient

Satisfaction with and Involvement of Networks

Overall, women reported that their DSPs participated in key activities related to their decision making. The majority of women reported that their DSPs often/always talked to them about their treatment options (74.2%) and frequently attended their appointments (73.3%), and these activities were more common among partnered women when compared to non-partnered women (both p<0.001). However, women overall were less likely to report that their DSPs had taken notes (50.5%), or shared treatment information with them from other sources (56.8%).

The majority of women were highly satisfied with their DSP being involved in their treatment decisions (76.5%) and over two-thirds (68.6%) felt their DSP was very important in their treatment decision making. However, both satisfaction and importance were significantly different across partner status; Partnered women were more likely to be highly satisfied and perceive their DSP to be of high importance compared to non-partnered women (both p<0.001). In addition, younger women, Black and Latina women and those with less education were more likely to perceive that their DSP was highly important (results not shown). (Table 2)

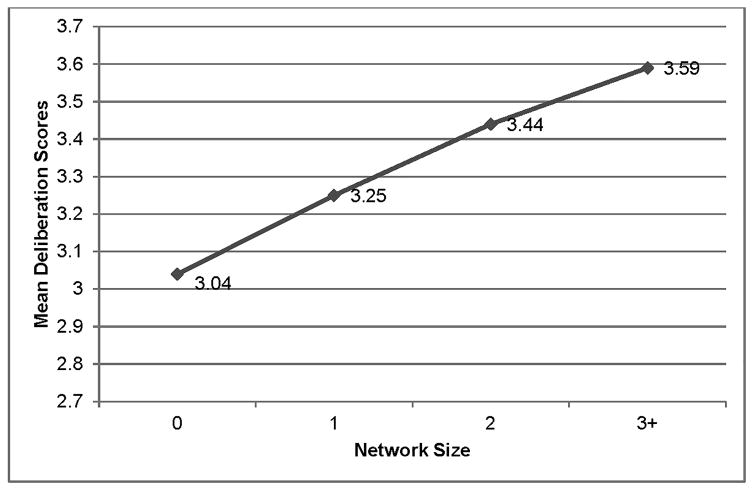

Association with Decision Deliberation

There was a significant association between network size and treatment deliberation scores, after adjustment for age, race, insurance, partner status, comorbidity, SEER stage, and surgical treatment. Mean treatment deliberation scores were lowest among women who had a network size of zero (mean deliberation score=3.04), and highest among women with a network size of 3 or more (mean deliberation score=3.59) (p<0.001). (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Adjusted mean deliberation scores by network size (p<0.001). Adjusted for age, race, insurance, education, partner status, comorbidity, SEER stage, and surgical treatment.

DISCUSSION

In this study that used a unique methodology to understand how family and friends contribute to the treatment decisions made by breast cancer patients, most reported having a large informal decision support network and also felt their supporters were both important and influential. Women with larger networks also reported more deliberative surgical treatment decisions, a promising outcome particularly at a time where there is concern that patients are rushing into making breast cancer treatment decisions.23–25 Our results suggest that engaging DSPs in the treatment decision process may be an important mechanism for slowing these decisions down, potentially allowing patients to more deeply consider them.

Our findings confirm prior work showing that most women do not make their breast cancer treatment decisions on their own, and instead heavily involve other support people in these emotional and difficult decisions.1–6, 11, 26 Our study extends this work by revealing that the decision support network for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients is larger than previously understood. In fact, we found that the majority of breast cancer patients reported having large networks, defined in this study as having 3 or more informal DSPs, and we further discovered that these supporters often included family members and friends beyond just their partners or spouses. In our large sample of non-married/partnered women—not previously well represented in studies of informal support—we found that children and friends were commonly considered key DSPs. Yet, we also showed that even among married/partnered women, children and friends played an important DSP role. These results underscore the need recognize the significant impact of informal DSPs—partners, children, friends—in the treatment decision making process and choices of breast cancer patients.

As expected, we did find some variation in network size in different patient subgroups, with younger and minority women indicating they had larger decision support networks. Prior research suggests that racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to rely on family for emotional/spiritual support and caregiving functions,1, 27 but this is one of the first studies to show that this is also the case for decision support specifically. In addition, even though African American women tended to be partnered/married at lower rates in our sample, they still had large networks that supported their decision making. Likewise, Latina women with low acculturation also reported larger network sizes, underscoring that for minorities with potential language barriers that make communication with their physicians more challenging,13, 14 the inclusion of DSPs offer another opportunity to educate patients about their treatment options. Efforts by clinicians to engage with the DSPs of minority women and to recognize that women often have DSPs beyond their spouses or partners may be beneficial in ensuring information is communicated in a culturally sensitive and understandable manner.

Our results also suggest that informal DSPs are actively engaged with patients throughout their treatment decision making and that there may be a real benefit to having a decision support network during this process. In addition to there being a strong association between the number of supporters and more treatment deliberation, the majority of women in this sample also reported they were highly satisfied with their DSPs’ level of involvement and felt they played an important role in their treatment decision making. Prior work from Shin and colleagues also suggests that patients and caregivers value family involvement in cancer treatment decision making.11, 26 Our findings that the majority of women also reported having DSPs who often attended their appointments, took notes, discussed their treatment options and shared information with them from other sources suggests that support networks are also highly involved throughout the decision process. This involvement may be particularly helpful around the time of diagnosis when patients are struggling to absorb information while simultaneously coping with their cancer diagnosis. It also suggests that they may be a benefit to addressing decision supporters within structured tools, or decision aids, designed to improve treatment decision making. While there are many decision aids available for breast cancer patients, none of them currently address the role of informal supporters in helping women navigate these treatment decisions and none directly engage supporters. Therefore, future decision aids and other interventions focused on improving breast cancer decision making should address the role of the DSP more directly.

Taken together, the results from this study suggest that the involvement of informal supporters in breast cancer treatment decisions provides an opportunity for clinicians to better incorporate them into these treatment decisions. Clinicians should be aware that women who include more informal decisions supporters in their treatment decisions may take longer to fully weigh treatment options and require additional time to make value- and preference-concordant decisions. Therefore, clinicians might discuss with patients the availability of informal DSPs and encourage their involvement early in the treatment consultation process. Clinicians should also anticipate delivering treatment information to at least one person beyond the patient and should also realize that among married/partnered women, the spouse/partner is not necessarily the family member that the patient considers to be her informal decision support person. Equally important, however, is recognizing that women who do not have an informal support person—as reported by 10% of patients in our sample, including a small proportion of women who were married/partnered, may be vulnerable to lower quality treatment decisions and may thus require additional decisional support.

While this study was a large population-based survey in a diverse sample with a high survey response rate, there are some potential limitations that merit consideration. This was a cross-sectional survey, and therefore inferences regarding causality are limited. We relied on patient report of their DSPs, including their influence and importance, which may be subject to recall bias. However, we captured this information on average only 2 months after surgery, thus minimizing the potential for this bias. We only asked women to identify up to three DSPs, and thus our estimates about the size of the decision support networks are most likely conservative. Finally, this sample only included women treated for breast cancer in Georgia and Los Angeles, and thus the generalizability of our findings may be limited.

CONCLUSIONS

Although prior research on breast cancer treatment decision making has tended to focus on the patient, our study is one of the largest to date that highlights the need to consider patients in the context of their informal decision support networks. Patients turn to others, including spouses, children, and friends, to help support them in these difficult and complicated decisions and these others are actively involved in helping patients make these decisions. The effectiveness of future initiatives to improve treatment decision making among breast cancer patients, including decision support tools, may be limited if they do not acknowledge and engage informal decision supporters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

This work was funded by grant P01CA163233 to the University of Michigan from the National Cancer Institute and by grant RSG-14-035-01 from the American Cancer Society.

Cancer incidence data collection was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003862-04/DP003862; the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California (USC), and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute.

Cancer incidence data collection in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201300015I, Task Order HHSN26100006 from the NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875-04-00 from the CDC. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. The State of California, Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC and their Contractors and Subcontractors had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We acknowledge the work of our project staff (Mackenzie Crawford, M.P.H. and Kiyana Perrino, M.P.H. from the Georgia Cancer Registry; Jennifer Zelaya, Pamela Lee, Maria Gaeta, Virginia Parker, B.A. and Renee Bickerstaff-Magee from USC; Rebecca Morrison, M.P.H., Alexandra Jeanpierre, M.P.H., Stefanie Goodell, B.S., Paul Abrahamse, M.A., Irina Bondarenko, M.S. and Rose Juhasz, Ph.D. from the University of Michigan). We acknowledge with gratitude our survey respondents.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

Lauren Wallner: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing original draft, writing review and editing, and visualization

Yun Li: methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft, writing review and editing, and visualization

M. Chandler McLeod: methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft, writing review and editing, and visualization

Ann Hamilton: investigation, resources, writing review and editing, and project administration

Kevin Ward: investigation, resources, writing review and editing, and project administration

Christine Veenstra: writing original draft, writing review and editing, and visualization

Lawrence An: conceptualization, investigation, and writing review and editing

Nancy Janz: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing review and editing

Steven Katz: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing original draft, writing review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition

Sarah Hawley: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing original draft, writing review and editing, and visualization

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Ratliff CT, Leake B. Racial/ethnic group differences in treatment decision-making and treatment received among older breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2006;106:957–965. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Leake B, Silliman RA. Determinants of participation in treatment decision-making by older breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85:201–209. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025408.46234.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1337–1347. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stiggelbout AM, Jansen SJ, Otten W, Baas-Thijssen MC, van Slooten H, van de Velde CJ. How important is the opinion of significant others to cancer patients’ adjuvant chemotherapy decision-making? Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohlen J, Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL, Brazier AS. The influence of significant others in complementary and alternative medicine decisions by cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1625–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbar R, Gilbar O. The medical decision-making process and the family: the case of breast cancer patients and their husbands. Bioethics. 2009;23:183–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R, Hawkins RP. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:474–486. doi: 10.1002/pon.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeSeure P, Chongkham-Ang S. The Experience of Caregivers Living with Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. J Pers Med. 2015;5:406–439. doi: 10.3390/jpm5040406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner CD, Tanmoy Das L, Bigatti SM, Storniolo AM. Characterizing burden, caregiving benefits, and psychological distress of husbands of breast cancer patients during treatment and beyond. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:E21–30. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31820251f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lillie SE, Janz NK, Friese CR, et al. Racial and ethnic variation in partner perspectives about the breast cancer treatment decision-making experience. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:13–20. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin DW, Cho J, Roter DL, et al. Attitudes Toward Family Involvement in Cancer Treatment Decision Making: The Perspectives of Patients, Family Caregivers, and Their Oncologists. Psycho-Oncology. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawley ST, Jagsi R, Morrow M, et al. Social and Clinical Determinants of Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:582–589. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawley ST, Janz NK, Hamilton A, et al. Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:1058–1067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi H, Heisler M. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care. 2011;49:37–45. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f37d28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: a meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkhalter S, Gastil J, Kelshaw T. A Conceptual Definition and Theoretical Model of Public Deliberation in Small Face—to—Face Groups. Communication Theory. 2002;12:398–422. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallner LP, Abrahamse P, Uppal JK, et al. Involvement of Primary Care Physicians in the Decision Making and Care of Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3969–3975. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallner LP, Martinez KA, Li Y, et al. Use of Online Communication by Patients With Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer During the Treatment Decision Process. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1654–1656. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2022–2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grovers RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, et al. Survey methodology. 2. Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman LA. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: Is it a reasonable option? JAMA. 2014;312:895–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schonberg MA, Birdwell RL, Bychkovsky BL, et al. Older women’s experience with breast cancer treatment decisions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:211–223. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2921-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz SJ, Morrow M. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer: Addressing peace of mind. JAMA. 2013;310:793–794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.101055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin DW, Cho J, Roter DL, et al. Preferences for and experiences of family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: patient-caregiver dyads study. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2624–2631. doi: 10.1002/pon.3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, et al. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e15–29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.