Abstract

The prompt and tightly controlled induction of type I interferon is a central event of the immune defense against viral infection. Flaviviruses comprise a large family of arthropod-borne positive-stranded RNA viruses, many of which represent a serious threat to global human health due to their high rates of morbidity and mortality. All flaviviruses studied so far have been shown to counteract the host’s immune response to establish a productive infection and facilitate viral spread. Here, we review the current knowledge on the main strategies that human pathogenic flaviviruses utilize to escape both type I IFN induction and effector pathways. A better understanding of the specific mechanisms by which flaviviruses activate and evade innate immune responses is critical for the development of better therapeutics and vaccines.

Keywords: Flaviviruses, innate immunity, type I interferon, viral innate immune evasion, interferon antagonism

1. INTRODUCTION

“It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place” – Through the looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll.

Leigh Van Valen, the founder of the “Red Queen Hypothesis”, used the Red Queen as a metaphor of the evolutionary arms races that are common to several genetic conflicts including host-pathogen interactions [1]. As a consequence of the selection pressure, throughout evolution eukaryotes developed sophisticated mechanisms to recognize and contain viral infections, and viruses in turn adapted multiple tricks to disrupt host defense pathways and hijack host processes to their advantage [2–4].

Type I interferons (IFNs) are a family of cytokines with essential roles in the defense of mammalian cells against viral infection and in the activation of immune responses. IFN was originally discovered more than 50 years ago by Isaacs and Lindenmann as a soluble factor produced by influenza virus-infected cells, and able to suppress subsequent infection with homologous or heterologous viruses in vitro [5–7]. Since then, remarkable advances have been made in our understanding of how type I IFN is produced in response to different stimuli, and how IFN signaling reprograms cellular biology to establish an effective antiviral role, and to enhance adaptive immune responses. In addition, several viral innate immune evasion strategies have been uncovered, which highlights the importance of the IFN signaling pathway in controlling viral replication and pathogenesis. This is of particular importance, since a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which different viruses manipulate and subvert the host immune response may contribute to the development of new live attenuated vaccines and antiviral drugs.

Flaviviruses are arthropod-borne viruses with a global impact on public health. They include important human pathogens such as Dengue (DENV), Japanese encephalitis (JEV), West Nile (WNV), Yellow Fever (YFV), Zika (ZIKV), and Tick-borne encephalitis (TBEV) viruses, many of which are resurging and spreading to new environments [8, 9]. Typically, these viruses contain a 10–11 kb positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome that encodes a single polyprotein. After translation, the viral polyprotein localizes at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane where it is cleaved by viral and host proteases to generate three structural (C, prM and E), and seven non-structural (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B and NS5) proteins. The structural proteins form the virion and are involved in viral attachment, fusion, and assembly. The non-structural proteins regulate viral transcription and replication and are required to modulate host antiviral responses. Interestingly, like all studied positive-strand RNA viruses, flaviviruses hijack cytoplasmic membranes in order to build functional sites for protein translation, processing and RNA replication [10–15]. These sites, generally defined as replication compartments (RCs), are required to efficiently coordinate different steps of the viral life cycle and to shield replicating RNA from innate immunity surveillance [16, 17].

In this review, we provide an overview of the different strategies used by human pathogenic flaviviruses to antagonize type I IFN responses in order to establish a productive infection. We discuss both the passive and active mechanisms exploited by flaviviruses to prevent innate immune recognition by cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and subsequent IFN induction. In this regard, a particular focus is given to the recently described mechanisms of inhibition of the RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) and cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAS) - stimulator of the interferon gene protein (STING) pathways by DENV. In addition, we summarize several studies that, in the last 10 years, have contributed elucidating the mechanisms by which different flaviviruses impair the type I IFN signaling pathway.

2. INNATE IMMUNE SENSING OF FLAVIVIRUSES

As suggested by Isaacs and Lindenmann’s seminal studies, today we know that type I IFN is produced by infected cells upon sensing of conserved “non-self” signatures, also known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), by specific host PRRs (reviewed in [18–21]).

Depending on their subcellular localization, PRRs can be classified in two main categories. The first category includes the membrane bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs), TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9, that are predominantly expressed in immune cells and can sense extracellular PAMPs or virus-derived nucleic acids within the endosomal compartment [22, 23]. The second category consists of different families of intracellular PRRs that are expressed in the cytoplasm and/or the nucleus of most mammalian cell types. These include, among others, the RLRs retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA5), and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2), that specifically sense cytoplasmic non-self viral RNA [24–26]; and a group of cytosolic DNA sensors such as cGAS, that recognize pathogen-derived as well as cellular DNA in the cytoplasm [26, 27].

The innate immune response against flaviviruses is triggered primarily by the recognition of viral RNA by the cytoplasmic RLRs RIG-I and MDA5 [28–30]. Several studies suggest that RIG-I plays a critical early role in establishing effective immune responses to most flaviviruses, whereas the role of MDA5 appears to be virus-dependent and acting at later stages [29–31]. Although the specific RNA agonist that is recognized by cellular RLRs during flavivirus infection has not been yet identified, it has been shown that RIG-I binds to single-stranded RNA (ssRNAs) and short double-stranded RNA (dsRNAs) harboring 5’ tri- or di-phosphate moieties, whereas MDA5 preferentially senses long dsRNA usually generated during positive-sense RNA virus replication [32–34]. Upon viral RNA sensing, RLRs undergo a conformational change and associate with the mitochondrial antiviral signaling adaptor protein (MAVS) through homotypic caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD)-CARD interactions. This in turn leads to the activation of the inhibitor of kappa-B kinase epsilon (IKKε) and TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK-1), which phosphorylate the transcription factors nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). Thereafter, NF-kB and IRF3 translocate into the nucleus to drive the transcription of type I IFN genes and the induction of an antiviral state [24, 28].

In addition, the cGAS-mediated DNA sensing pathway has recently been implicated in flavivirus detection [35–38]. Following DNA binding, the cytoplasmic DNA sensor cGAS, a member of the nucleotidyl-transferase family, is activated and produces the second messenger cyclic-di-GMP-AMP (cGMP-AMP), which in turn activates the adaptor protein STING [39, 40]. STING is an ER-resident factor which dimerizes upon activation, and translocates to perinuclear structures to promote downstream signaling events, ultimately leading to type I IFN production [41].

Once secreted, type I IFNs bind to the IFN receptor (IFNAR) in an autocrine and paracrine manner [42, 43], and signal through the Janus kinase (JAK) – signal transducer and activator of (STAT) signaling pathway to trigger the expression of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) with antiviral and immunoregulatory functions [44–46]. Briefly, receptor binding and hetero-dimerization of the two IFNAR subunits activate the tyrosine kinases TYK2 and JAK1, leading to STAT2 and STAT1 phosphorylation [47–51]. Thereafter, STAT1 and STAT2 hetero-dimerize and interact with IFN regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) to form the ISG factor 3 (ISGF3) ternary complex [52–54]. ISGF3 then translocates to the nucleus where it binds to IFN-stimulated responsive elements (ISRE) and drives the expression of hundreds of ISGs [55, 56]. Some of these factors have been shown to have direct or indirect antiviral activity against flaviviruses [38, 57–61].

3. ANTAGONISM OF TYPE I IFN PRODUCTION

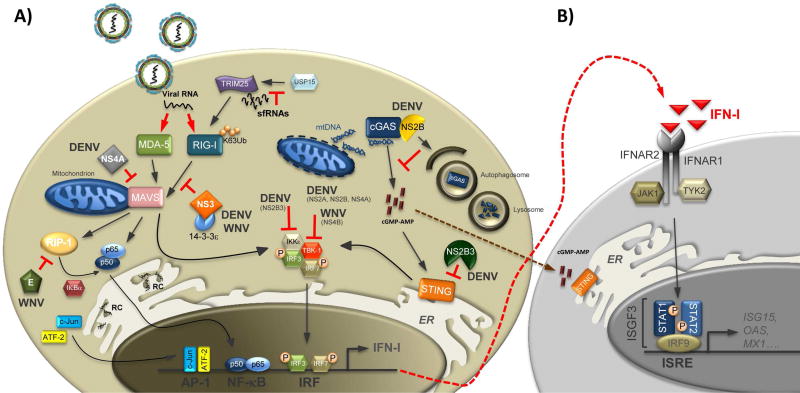

As eukaryotic cells have evolved several mechanisms to distinguish self from non-self nucleic acids, flaviviruses, like many other viruses, have developed different strategies to escape, or at least delay, innate immune recognition. Indeed, flaviviruses have been shown to be either weak inducers of type I IFN [62–64], or late-in-infection inducers, allowing a replicative advantage to the virus during the early replication stages [31]. A summary of the strategies used by different flaviviruses to counteract type I IFN production is presented below, and a scheme of these mechanisms is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Antagonism of type I IFN production by flaviviruses.

Upon recognition of viral RNA, RIG-I and MDA5 undergo a conformational change that triggers their interaction with the adaptor protein MAVS. This in turn induces a signaling cascade that results in IRF3 and NF-kB activation and type I IFN induction (IFN-I) (A). Secreted IFN-I then functions in an autocrine and paracrine fashion leading to the activation of an antiviral state (B). Flaviviruses are able to counteract the induction of type I IFN both in a passive and active fashion. The former functions by hiding flavivirus RNA from PRRs sensing, i.e. by sequestrating dsRNA replication intermediates at the RCs. The later takes place by several mechanisms, unique among different viruses: sfRNAs prevent USP15-mediated deubiquitination of TRIM25, and subsequent RIG-I activation; the NS3 protein of WNV competes with RIG-I for binding to the chaperone 14-3-3ε; the NS4A protein of DENV sequesters MAVS to block downstream signaling events; the structural E protein of WNV inhibits RIP-1 polyubiquitination and blocks the activation of NF-kB signaling. Moreover, DENV infection triggers the release of mtDNA into the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic mtDNA then binds to cGAS and activates downstream signaling. DENV is able to antagonize the DNA sensing pathway in two ways: the viral protease NS2B3 cleaves STING, and the NS2B protein promotes the degradation of cGAS by an autophagy-lysosome dependent mechanism. Additionally, several nonstructural proteins of both DENV (NS2B3, NS2B, NS2A, NS4A) and WNV (NS4B) have been shown to block the kinases IKKε and TBK-1, that are responsible for IRF3 activation and translocation into the nucleus.

Playing hide and seek: passive antagonism of innate immune sensing

There are two main passive mechanisms that flaviviruses use to hide from host sensing pathways and to subvert the innate immune response.

The first strategy consists in host RNA mimicry by modification of their viral RNA genomes. To that end, flaviviruses have evolved to incorporate a 2’-O-methyltransferase (2’-O-MTase) in their genome (within the NS5 gene). This 2’-O-MTase adds a methyl group at the penultimate 5’ nucleotide (7mGpppNm, Cap1) of the cap structure. In this way, the members of the interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats (IFIT) protein family are not able to bind and sequester the viral RNA to arrest viral protein production [57]. In fact, the WNV mutant E218A, that lacks the 2’-O-MTase activity, has been shown to be more sensitive to the antiviral effects of IFIT1, being attenuated in both primary cells and mice. However, this mutant is still pathogenic when type I IFN signaling is abrogated [57, 65].

The second passive mechanism employed by flaviviruses to subvert innate immune detection consists in the sequestration of their dsRNA replication intermediates within evolutionary conserved cytoplasmic membrane-wrapped RCs [11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 66–69]. These ER-derived double-membrane vesicles are believed to protect both dsRNA replication intermediates and replicated viral RNA from PRR sensing until there is enough progeny produced. This mechanism has been observed during the early stages of infection with DENV, WNV, and TBEV [16, 17, 66, 68, 70]. Regarding JEV, nevertheless, conflicting reports have arisen, as Morita group described diverse phenotypes in different cell lines. Infection of porcine cells with JEV showed a delayed IFN response due to the concealing of the viral RNA at the RC [71]. However, JEV infection of HeLa cells showed an earlier IFN induction pattern [68]. Additionally, in a more recent study the authors observed that the presence of the viral-derived RNA in the cytoplasm at the early stages of infection, and therefore the timing of IFN induction, depends on the cell type used for their experiment [72]. Altogether, this suggests that differences in RNA leaking from the vesicles to the cytosol among cell lines could be influenced by a cell type-specific conformation of the double-membrane vesicles or other host factors. Further investigation is needed to fully clarify these issues.

Here comes the action: active antagonism of RLR signaling

As mentioned above, a prompt activation of the RIG-I-mediated signaling pathway is required for the establishment of an effective immune response against flaviviruses. Importantly, several studies have shown that protein post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, play a critical role in the regulation of the RIG-I pathway at different levels [73]. In addition, several different viruses have been shown to interfere with these PTMs in order to dampen immune signaling events [74–77]. After viral RNA binding, RIG-I undergoes a conformational change leading to the release of the CARD domains and subsequent interaction with the E3 ubiquitin-ligase tripartite motif protein 25 (TRIM25). TRIM25 is a member of the TRIM family of proteins, many of which are important regulators of the PRR signaling pathways [78–80]. Specifically, TRIM25 has been shown to interact with the first CARD of RIG-I and to promote K63-linked ubiquitination of the RIG-I’s Lys172 residue, RIG-I tetramerization, and MAVS interaction [81–83]. In addition, TRIM25 activity itself is also regulated by PTMs mediated by the ubiquitin specific protease15 (USP15), and the linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) [84].

Interestingly, Manokaran and colleagues have recently shown that DENV infection is able to prevent USP15-mediated deubiquitination of TRIM25, and subsequent RIG-I activation, through the production of viral subgenomic flavivirus RNAs (sfRNAs) [77]. sfRNAs are highly structured non-coding RNAs of ~0.3–0.5 kb that derive from incomplete degradation of the viral RNA genome by the host exonuclease Xrn1, and that are essential for flavivirus pathogenesis [85–87]. The role of sfRNAs in antagonizing the type I IFN response was previously reported by Schuessler and colleagues, who demonstrated that a WNV mutant that is not able to generate sfRNA is attenuated in vivo [88]. However, the sfRNA mechanism of action was yet to be revealed. In their new study, Manokaran and colleagues observed that DENV sfRNAs directly bind TRIM25 to inhibit downstream signaling, and that the relative levels of sfRNA with respect to genomic RNA (gRNA) vary depending on the viral strain. In particular, the sfRNA/gRNA ratio appeared to be higher for epidemic DENV viruses and for inducers of antibody dependent enhancement. Furthermore, sfRNA-TRIM25 binding was stronger for the endemic DENV isolate PR-2B than for the previously circulating DENV PR-1 strain [77]. Interestingly, a publication by the Gamarnik group in collaboration with our group recently highlighted an important role of DENV sfRNAs also in dictating viral fitness in different hosts. The authors observed that mosquito- and human-adapted viruses acquire specific mutations in their 3’UTRs that result in different sfRNA patterns, and different viral fitness in each host. For instance, mosquito-adapted viruses were shown to accumulate specific sfRNA patterns with limited ability to counteract the antiviral response in human cells, and therefore exhibited reduced viral fitness in the mammalian host. However, it remains to be determined whether an impaired sfRNA-TRIM25 interaction is contributing to this phenotype. Interestingly, ZIKV did not present this change on sfRNA patterns between hosts, neither between epidemic and pre-epidemic strains, indicating that the two viruses evolved under different selective pressures [89]. More research is needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which sfRNAs regulate the strength of the immune response and viral fitness in different hosts.

RIG-I signaling is also regulated by the chaperone 14-3-3ε, which is responsible for directing RNA-bound activated-RIG-I to the mitochondrial membrane. Mitochondrial localization of activated-RIG-I in turn allows RIG-I-MAVS interaction, and promotes the subsequent activation of downstream signaling events [90]. To counteract 14-3-3ε activity, DENV and WNV have developed a phosphomimetic-based mechanism mediated by their NS3 proteins. DENV and WNV NS3 present a highly conserved aminoacid motif (‘64-RxEP-67’ and ‘64-RLDP-67’, respectively), which mimics the 14-3-3ε binding domain of RIG-I [Rxx(pS/pT)xP]. Hence, the NS3 protein competes with RIG-I for 14-3-3ε binding, and impairs the translocation of the activated-RIG-I complex to the mitochondrial membrane [91]. Furthermore, He and colleagues recently observed that the NS4A protein of DENV sequesters the adaptor protein MAVS to counteract RLR signaling. Mechanistically, NS4A binds to both the N-terminal and the C-terminal domains of MAVS, and prevents RIG-I-MAVS interaction, blocking IRF3 activation and type I IFN production [92].

It takes two to tango: active antagonism of the DNA sensing pathway

The key role of the cGAS-STING pathway in the innate immune response to RNA virus infection has recently emerged, in particular in the context of DENV infection. Interestingly, DENV has been shown to counteract the sensing and IFN production by the cGAS-STING pathway at two different levels. The fact that DENV has evolved more than one mechanism to counteract this route highlights its importance within the innate immune response to DENV infection.

It was first shown by our group that the non-structural protein NS2B3, the protease complex of DENV, was able to inhibit type I IFN expression in infected monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDCs) [63, 93]. Later, we and others identified that STING has a predominant role in the recognition of DENV by the innate immune system, and that DENV NS2B3 counteracts this pathway by specifically cleaving STING [36, 37]. This antagonism results in lack of type I IFN production in those cells but does not affect the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Infection with positive strand RNA viruses, including flaviviruses, was known to trigger cGAS-dependent IFN induction [38]. This is somehow surprising, as this pathway senses cytoplasmic DNA, and positive strand RNA virus replication involves only RNA molecules. Only recently, the mechanism of induction of the cGAS sensing pathway by these viruses has started to be revealed. Our group proposed that one common feature among positive RNA viruses, the induction of extensive membrane rearrangements and distress after viral infection, could be a determinant for this activation. Indeed, we observed that during DENV infection mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is released into the cytoplasm and acts as a danger associated molecular pattern (DAMP) to trigger cGAS-dependent type I IFN induction [35]. In order to counteract this signaling pathway, DENV interacts with cGAS through the protease co-factor NS2B, and promotes its degradation by an autophagy-lysosome dependent mechanism [35]. As cGAS can also function in a paracrine fashion, through cGMP-AMP transfer to neighboring cells [94], by counteracting both STING and cGAS, DENV ensures that the cGAS-STING pathway remains blocked upon viral infection. This is the first report of a viral protein targeting cGAS for degradation. It will be important to assess if other flaviviruses also exploit a similar mechanism to alter such a crucial pathway for type I IFN production.

Let’s fight them all: active antagonism downstream PRRs

Some structural and non-structural proteins from flaviviruses have also been reported to counteract key signaling molecules downstream of the PRRs.

Receptor interacting Ser/Thr kinase 1 (RIP-1) is a molecule recruited and activated by MAVS upon either RLR or TLR3 stimulation that triggers the signaling of the NF-kB pathway. The structural protein E of WNV, the first viral protein that interacts with the host during infection, has been shown to specifically inhibit RIP-1 polyubiquitination in murine macrophages. As a consequence, NFKB inhibitor alpha (IkBα) is not efficiently degraded, leading to an inhibition of NF-kB signaling and to an impaired induction of type I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, the antagonistic activity of the WNV E protein requires a specific N-linked glycosylation pattern, which is obtained after viral growth in mosquito cells, but not in mammalian cells [95].

The two main kinases responsible for IRF3 activation, IKKε and TBK-1, which are involved in both RLR and cGAS-STING pathways, are also targeted by flaviviruses. First, the protease NS2B3 of DENV (in particular, DENV2) has been shown to interact with IKKε, blocking IRF3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. This effect also takes place with a catalytically inactive NS2B3, although to a lesser extent [96]. Second, TBK-1 can be counteracted by the non-structural proteins NS2A and NS4B of all the DENV strains tested (DENV1, 2 and 4), by NS4A of just DENV1, and by NS4B of WNV. Ectopic expression of these non-structural proteins has been shown to inhibit TBK-1 autophosphorylation, and therefore IRF3 phosphorylation and type I IFN transcription [97]. Additionally, the NS2A protein of the naturally attenuated WNV strain Kunjin (KUN) has also been observed to block type I IFN induction. Expression of a KUN RNA replicon with a point mutation (A30P) in the NS2A gene resulted in lower levels of inhibition of the IFNß promoter transcription than expression of a wild type KUN replicon [98]. Moreover, a recombinant KUN virus carrying the same A30P mutation in the NS2A gene showed attenuated neuroinvasiveness and neurovirulence in vivo [98, 99].

Altogether, these studies demonstrate that DENV and WNV are invested in antagonizing critical factors for the production of type I IFN downstream the PRRs. Nevertheless, more research would be needed to fully understand the mechanisms involved, and their relevance in other flaviviral species.

4. ANTAGONISM OF TYPE I IFN SIGNALING

As mentioned above, type I IFN plays an essential role for the control of viral infection. To date, several studies have shown that pretreatment with type I IFN can inhibit flavivirus replication in vitro, and it is important to control viral replication and spread in vivo. Specifically, mouse strains that are deficient in the type I IFN receptor, or in key components of the IFN signaling pathway such as STAT1 and STAT2, show enhanced lethality and viral replication upon infection with WNV [100, 101], DENV [102–104], YFV [105, 106], and ZIKV [107, 108]. However, it is also well known that treatment with IFN is much less effective after the infection is already established [100, 109–112]. Moreover, despite significant amount of IFN in their plasma, DENV infected patients can still exhibit elevated viral titers [113], and JEV is not sensitive to IFN in clinical trials neither in JE patients [114].

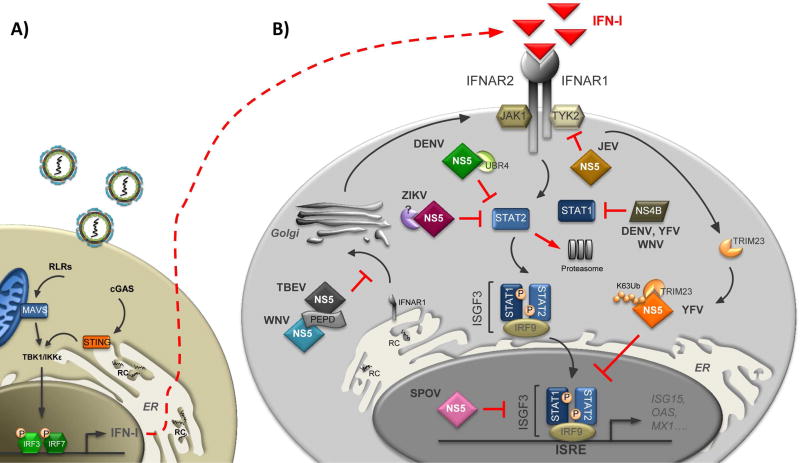

All together, these observations strongly suggest that flaviviruses have evolved mechanisms to circumvent IFN antiviral activity, and establish a productive infection. Indeed, every human-pathogenic flavivirus studied so far has been shown to impair type I IFN signaling through the activity of its non-structural proteins. Intriguingly, the NS5 protein, the most conserved flaviviral protein, which encodes the viral MTase and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), also constitutes the most potent and specific antagonist of this signaling pathway. The precise mechanisms exploited by the different flaviviruses to inhibit type I interferon signaling are discussed below and summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Antagonism of type I IFN signaling by flaviviruses.

Mammalian cells sense flavivirus infection mainly via cytoplasmic PRRs such as the RLRs and the DNA sensor cGAS, which in turn activate their adaptor proteins MAVS and STING, respectively. This event initiates downstream signaling cascades ultimately leading to type I IFN (IFN-I) production (A). Once secreted, IFN-I binds to the IFN-I receptor (IFNAR1/IFNAR2) in an autocrine and paracrine manner, and activates the JAK/STAT signaling pathway to trigger an antiviral state (B). Flaviviruses have evolved multiple mechanisms to counteract IFN-I-dependent signaling. JEV NS5 blocks TYK2 phosphorylation. The NS5 proteins of DENV and ZIKV bind to STAT2 and trigger STAT2 proteasomal-degradation. YFV NS5 binds STAT2 upon IFN-I stimulation and TRIM23-dependent ubiquitination. Ubiquitinated YFV NS5 then inhibits ISGF3-driven transcription. SPOV NS5 prevents ISGs transcription in the nucleus trough an uncharacterized mechanism. TBEV and WNV interfere with maturation of the IFNAR1 receptor subunit through the activity of their NS5 proteins. The NS4B proteins of DENV, YFV, and WNV block STAT1 phosphorylation.

Inhibition of IFN signaling by DENV

The ability of an arthropod-born human flavivirus to inhibit type I IFN signaling was demonstrated for the first time by Munoz-Jordan and colleagues from our group [115]. In that report, in order to identify the viral proteins responsible for this inhibition, the authors individually expressed all DENV2 proteins in A549 cells and found that NS4B, and to a lesser extent NS2A and NS4A, were able to enhance the replication of the IFN-sensitive Green Fluorescence Protein-tagged Newcastle disease virus (NDV-GFP), as well as to inhibit the activation of the ISRE promoter upon IFN stimulation. Mechanistically, DENV infected cells, or NS4B-expressing cells, exhibited impaired STAT1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in response to IFN treatment. Interestingly, NS4B’s function appeared to be conserved among mosquito-borne flaviviruses such as DENV, YFV and WNV [116, 117]. Furthermore, proper post-translational cleavage of the viral polyprotein at the NS4A/B region, and proper targeting of the NS4B protein to the ER membrane, appeared to be critical for IFN antagonism, as shown in a subsequent report from our group [116].

Besides inhibiting STAT1 phosphorylation as described above, we and others went on to show that infection with DENV also promotes ubiquitin-dependent STAT2 proteasomal degradation [118, 119]. Interestingly, ectopically expressed NS5 is able to interact with the coiled-coil domain of human STAT2 and to inhibit IFN signaling [103, 118, 120]. However, only a proteolitically-processed NS5, which mimics the cleaved form of NS5 produced in the context of DENV infection, can trigger STAT2 degradation by co-opting the ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component n-recognin 4 (UBR4) [118, 120, 121]. UBR4 binds preferentially to the cleaved form of DENV NS5, and does not bind YFV, WNV or ZIKV NS5 [121, 122]. In addition, the first 10 amino acids of NS5, and in particular Thr2 and Gly3, that are conserved amongst the 4 DENV serotypes, but not in other flaviviruses, have been identified by our group as the critical residues for UBR4 binding and STAT2 degradation [121]. The critical role of the DENV NS5-UBR4 interaction in IFN antagonism was also confirmed by showing that UBR4 expression is required for optimal viral replication in IFN competent cells [121]. Additional work is needed to unravel the molecular details of how DENV NS5 and UBR4 trigger STAT2 degradation.

Inhibition of IFN signaling by ZIKV

The antagonism of type I IFN signaling by ZIKV shares multiple similarities with that of DENV. A recent report from our group showed that, like DENV NS5, ZIKV NS5 also binds and degrades human STAT2 via the proteasome [122]. However, the mechanisms exploited by the two viruses appear to be different. ZIKV-mediated STAT2 degradation does not require proteolytic processing of the NS5 N-terminus and is independent of UBR4. Furthermore, domain mapping has suggested that ZIKV NS5 interacts with STAT2 through its MTase domain, and that, unlike DENV NS5, the first 10 amino acid residues of ZIKV NS5 are not critical for STAT2 degradation [123]. Future studies aimed at elucidating the mechanism and the additional host factors required for ZIKV-mediated STAT2 degradation will be particularly important for the development of effective antiviral strategies to treat ZIKV infections.

Inhibition of IFN signaling by YFV and Spondweni virus (SPOV)

The prototypic flavivirus YFV, which recently re-emerged in Angola and Democratic Republic of Congo causing the largest yellow fever outbreak in almost 30 years, has also been shown to efficiently antagonize type I, but not type II, IFN signaling in its primate hosts. Strikingly, our group has recently found that to bind STAT2 and inhibit ISGF3 engagement with ISREs, YFV NS5 requires type I IFN treatment [124]. Indeed, type I IFN activates YFN NS5 antagonistic function in several ways. First of all, it induces STAT1 phosphorylation and the formation of STAT1/STAT2 heterodimers. This event then results in a STAT2 conformational change and in the exposure of the NS5 binding domain. Second, by a still uncharacterized mechanism, type I IFN activates the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM23 that in turn promotes K63-linked polyubiquitination of YFV NS5 at Lys6 (K6). The authors convincingly show that ubiquitination at position 6 of the YFV NS5 protein is critical for STAT2 binding and for inhibition of IFN signaling. Indeed, mutation of NS5 K6 to an Arg (NS5 K6R) is sufficient to abolish STAT2 binding upon IFN stimulation. In addition, a YFV-17D recombinant virus carrying the NS5 K6R mutation displayed enhanced susceptibility to type I IFN in cell culture [124]. These findings may potentially be used to improve the safety of the current YFV-17D vaccine by helping to generate a more attenuated virus strain.

Interestingly, similar to YFV, SPOV, the closest relative of ZIKV, was also shown to inhibit IFN signaling more downstream in the pathway. Ectopic expression of the SPOV NS5 protein strongly suppresses IFN-induced ISRE-dependent gene expression. However, SPOV NS5 does not bind strongly to STAT1 or STAT2, and does not significantly affect their phosphorylation or expression level [122]. Therefore, SPOV must prevent ISRE-dependent ISGs transcription by a different mechanism such us by binding IRF9 or by interfering with ISGF3 binding to the ISRE promoter. Future studies will help to answer these questions.

Inhibition of IFN signaling by JEV and WNV

JEV and WNV belong to the same antigenic complex, and they both have been shown to interfere with the type I IFN response through the activity of their NS5 proteins. However, the specific mechanisms are different from the one used by DENV and ZIKV [125, 126].

WNV infection suppresses the IFN signaling pathway by blocking JAK1 and TYK2 activation and therefore preventing downstream events including STATs phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, and ISG expression [127]. In addition, WNV infection also triggers cholesterol redistribution to inhibit the formation of cholesterol rich lipid rafts at the plasma membrane and to attenuate IFN signaling [128]. Individual expression of several nonstructural proteins from the naturally attenuated KUN strain, but not KUN NS5 expression, was shown to be sufficient to block STATs phosphorylation [117]. However, the NS5 protein from the virulent NY99 WNV strain was later identified by Laurent-Rolle and colleagues in our group as a potent suppressor of the type I IFN response [126]. In the same study, the authors also compared the IFN antagonistic activity of the NS5 proteins from a virulent (JEV-N) and an attenuated (JEV-SA) JEV strain. Strikingly, also in this case the NS5 protein from the virulent JEV strain was proven to be a more potent IFN antagonist, pointing toward a critical role of the NS5 protein in influencing WNV and JEV virulence in humans [101, 126, 129]. However, whereas WNV NS5 has also been shown to downregulate IFNAR1 expression by binding to the host protein prolidase (PEPD) [130], the mechanism exploited by JEV to specifically block TYK2 phosphorylation and downstream signaling events has not been fully elucidated yet [110, 125].

Inhibition of IFN signaling by tick-borne flaviviruses

The NS5 proteins from tick-borne flaviviruses, such as TBEV and the attenuated Langat virus (LGTV), also function as effective IFN antagonists. LGTV infection was shown to inhibit the JAK-STAT signaling pathway by blocking the phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT2, JAK1, and TYK2 in response to type I and type II IFN stimulation [111]. To identify the viral protein(s) responsible for this effect, Best and colleagues individually expressed all LGTV non-structural proteins and tested their ability to inhibit STAT1 phosphorylation. Strikingly, LGTV NS5 alone significantly affected STAT1 phosphorylation and downstream signaling events. This was the first of many reports showing that the NS5 protein is the main IFN antagonist encoded by flaviviruses [111]. Subsequent domain mapping studies identified residues within the RdRp domain as critical for the IFN antagonistic function of LGTV NS5 [131]. Moreover, Lubick and colleagues recently revealed that the NS5 protein of TBEV, LGTV, and WNV targets the host protein PEPD to prevent surface expression of IFNAR1 and suppress ISG induction [130]. In support of these findings, a TBEV recombinant virus carrying an NS5 mutation that results in an impaired ability to downregulate IFNAR1 was also significantly attenuated in vivo [130]. This strongly suggests that NS5 plays a role in regulating virulence and pathogenesis.

5. TYPE I IFN AS A DETERMINANT OF HOST TROPISM

Mice are naturally resistant to infection with flaviviruses. However, as mentioned above, mouse strains that are deficient in key antiviral signaling pathways are highly susceptible to flavivirus infection. This restriction can be at least in part explained by the fact that many flaviviruses cannot efficiently block type I IFN induction and/or signaling in mice [36, 37, 103, 122]. In this regard, we and others have observed that while the DENV NS2B3 protease is able to bind and cleave human STING, it can only bind but not cleave murine STING [36, 37]. Importantly, the cleavage site for the DENV protease is not conserved in murine STING, and the introduction of the corresponding murine residues into the human protein makes it resistant to NS2B3-mediated cleavage. Consistently, overexpression of this uncleavable STING mutant in human MDDCs results in a stronger induction of IFN and in a reduction of the viral RNA levels upon DENV infection. In a similar way, we also consistently observed that, relative to human cells, infection of murine cells triggers a more robust STING-dependent type I IFN induction [36]. It would be very interesting to know whether STING also contributes to the host-specific restriction of other flaviviruses. Importantly, we also revealed that the NS5 proteins of both ZIKV and DENV can bind and degrade human STAT2, but not murine STAT2 [103, 122]. As a result, unlike wild-type mice, STAT2-deficient mice allow replication of both ZIKV and DENV [103, 107, 132]. All together these data strongly suggest that STING and STAT2 constitute two important species-specific restriction factors of flavivirus infection in mice. It is therefore likely that replacing murine STING and murine STAT2 with their human counterparts would help toward the development of an immune-competent mouse model to study flavivirus pathogenesis in vivo. Such a model would be extremely useful for the development of new vaccines and antiviral therapies.

SUMMARY and OUTLOOK

As summarized above, flaviviruses invest a big part of their genome to counteract both IFN induction and effector pathways, and establish a successful infection in humans. This emphasizes the importance of bypassing the early type I IFN response for effective viral replication. To date, the NS5 proteins of several flaviviruses have emerged as the most potent active antagonists of type I IFN signaling. However, the mechanisms of NS5 inhibition are different among flavivirus species, suggesting that this NS5 function arose independently several times throughout evolution. A likely explanation for this is that the NS5 protein is the largest nonstructural protein and it is produced in excess in the infected cells, perhaps increasing the possibility to acquire additional functions. As the NS5 protein has also been shown to be phosphorylated and ubiquitinated in infected cells, it will be important in the future to study how PTMs regulate NS5 antagonistic functions in different hosts.

In contrast to the extensive studies on the role of the nonstructural proteins in blocking type I IFN signaling, the strategies exploited by flaviviruses to counteract IFN induction only recently begun to be unraveled. In particular, our recent observation that cGAS can sense mtDNA that is released into the cytoplasm of DENV-infected cells to trigger IFN induction paves the way to a new exciting area of research. It will be very interesting in the future to understand whether similar mechanisms of antagonism of the DNA sensing pathway are common to other flaviviruses as well as to other positive-stranded RNA viruses in general. This perhaps wouldn’t be surprising since they all relay on extensive reorganization of the intracellular membranes for their replication, and this may lead to virus-induced mitochondrial stress and mtDNA release.

Furthermore, it will be also very important to identify the specific ISGs that possess key antiviral activity against flaviviruses, to characterize their mechanisms of action, and to understand whether these viruses have evolved strategies to antagonize their functions.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Flaviviruses are arthropod-borne viruses, many of which represent an expanding threat to public health worldwide.

Type I Interferons are key innate immune regulators for antiviral defense.

Flaviviruses have evolved multiple strategies to overcome innate immune detection and ensure viral replication and spread.

This evolutionary struggle for survival results in a balance for coexistence of both hosts and viruses.

Acknowledgments

We thank all past and present members of the Fernandez-Sesma and García-Sastre laboratories for their precious contribution to several of the studies discussed in this review. We apologize to all colleagues whose important work could not be cited due to space constraints. Current flavivirus research in the García-Sastre laboratory is supported by the NIH/NIAID grant U19AI1186101. Flavivirus research in the Fernandez-Sesma laboratory discussed in this review has been supported by the NIH/NIAID grants R01AI07345, R21AI116022 and U19AI1186101 and the DoD/DARPA grant HR0011-11-C-0094.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- 2’-O-MTase

2’-O-methyltransferase

- CARD

caspase activation and recruitment domain

- cGAS

cyclic GMP-AMP synthase

- cGMP-AMP

cyclic-di-GMP-AMP

- DAMP

danger associated molecular pattern

- DENV

dengue virus

- dsRNAs

double-stranded RNA

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- gRNA

genomic RNA

- IFIT

interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats

- IFNAR

interferon receptor

- IFNs

type I interferons

- IkBα

NFKB inhibitor alpha

- IKKε

inhibitor of kappa-B kinase epsilon

- IRF3

interferon regulatory factor 3

- IRF9

interferon regulatory factor 9

- ISGF3

ISG factor 3

- ISGs

interferon-stimulated genes

- ISRE

interferon-stimulated responsive elements

- JAK

Janus kinase

- JEV

Japanese encephalitis virus

- KUN

WNV strain Kunjin

- LGP2

laboratory of genetics and physiology 2

- LGTV

Langat virus

- LUBAC

linear ubiquitin assembly complex

- MAVS

mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein

- MDA5

melanoma differentiation associated gene 5

- MDDCs

monocyte-derived dendritic cells

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- NF-kB

nuclear factor kappa B

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PEPD

prolidase protein

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- RCs

replication compartments

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- RIG-I

retinol acid-inducible gene I

- RIP-1

receptor interacting Ser/Thr kinase 1

- RLRs

RIG-I like receptors

- sfRNAs

subgenomic flavivirus RNAs

- SPOV

Spondweni virus

- ssRNAs

single-stranded RNA

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- STING

stimulator of the interferon gene protein

- TBEV

tick-borne encephalitis virus

- TBK-1

TANK binding kinase 1

- TLRs

toll-like receptors

- TRIM25

tripartite motif protein 25

- TYK2

tyrosine kinase 2

- UBR4

Ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component n-recognin 4

- USP15

Ubiquitin specific protease15

- WNV

West Nile virus

- YFV

Yellow Fever virus

- ZIKV

Zika virus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Elde NC, Malik HS. The evolutionary conundrum of pathogen mimicry. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:787–797. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Versteeg GA, Garcia-Sastre A. Viral tricks to grid-lock the type I interferon system. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Sastre A, Biron CA. Type 1 interferons and the virus-host relationship: a lesson in detente. Science. 2006;312:879–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1125676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.tenOever BR. The Evolution of Antiviral Defense Systems. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacs A, Lindenmann J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1957;147:258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaacs A, Lindenmann J, Valentine RC. Virus interference. II. Some properties of interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1957;147:268–273. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacs A, Westwood MA. Duration of protective action of interferon against infection with West Nile virus. Nature. 1959;184(Suppl 16):1232–1233. doi: 10.1038/1841232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackenzie JS, Gubler DJ, Petersen LR. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat Med. 2004;10:S98–109. doi: 10.1038/nm1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DR. Waiting in the wings: The potential of mosquito transmitted flaviviruses to emerge. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016:1–18. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1230974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul D, Bartenschlager R. Flaviviridae Replication Organelles: Oh, What a Tangled Web We Weave. Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:289–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Boon JA, Ahlquist P. Organelle-like membrane compartmentalization of positive-strand RNA virus replication factories. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:241–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero-Brey I, Bartenschlager R. Membranous replication factories induced by plus-strand RNA viruses. Viruses. 2014;6:2826–2857. doi: 10.3390/v6072826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Bleck CK, Walther P, Fuller SD, Antony C, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miorin L, Romero-Brey I, Maiuri P, Hoppe S, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R, Marcello A. Three-dimensional architecture of tick-borne encephalitis virus replication sites and trafficking of the replicated RNA. J Virol. 2013;87:6469–6481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03456-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortese M, Goellner S, Acosta EG, Neufeldt CJ, Oleksiuk O, Lampe M, Haselmann U, Funaya C, Schieber N, Ronchi P, Schorb M, Pruunsild P, Schwab Y, Chatel-Chaix L, Ruggieri A, Bartenschlager R. Ultrastructural Characterization of Zika Virus Replication Factories. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2113–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miorin L, Albornoz A, Baba MM, D’Agaro P, Marcello A. Formation of membrane-defined compartments by tick-borne encephalitis virus contributes to the early delay in interferon signaling. Virus Res. 2012;163:660–666. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Overby AK, Popov VL, Niedrig M, Weber F. Tick-borne encephalitis virus delays interferon induction and hides its double-stranded RNA in intracellular membrane vesicles. J Virol. 2010;84:8470–8483. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00176-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber GN. Cytoplasmic DNA innate immune pathways. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwasaki A. A virological view of innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:177–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Chen ZJ. Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:461–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoneyama M, Onomoto K, Jogi M, Akaboshi T, Fujita T. Viral RNA detection by RIG-I-like receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;32:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lester SN, Li K. Toll-like receptors in antiviral innate immunity. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:1246–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akira S. TLR signaling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:1–16. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel JR, Garcia-Sastre A. Activation and regulation of pathogen sensor RIG-I. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato H, Takahasi K, Fujita T. RIG-I-like receptors: cytoplasmic sensors for non-self RNA. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goubau D, Deddouche S, Reis e Sousa C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity. 2013;38:855–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paludan SR, Bowie AG. Immune sensing of DNA. Immunity. 2013;38:870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Tsujimura T, Koh CS, Reise Sousa C, Matsuura Y, Fujita T, Akira S. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fredericksen BL, Keller BC, Fornek J, Katze MG, Gale M., Jr Establishment and maintenance of the innate antiviral response to West Nile Virus involves both RIG-I and MDA5 signaling through IPS-1. J Virol. 2008;82:609–616. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01305-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo YM, Fornek J, Crochet N, Bajwa G, Perwitasari O, Martinez-Sobrido L, Akira S, Gill MA, Garcia-Sastre A, Katze MG, Gale M., Jr Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J Virol. 2008;82:335–345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01080-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredericksen BL, Gale M., Jr West Nile virus evades activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 through RIG-I-dependent and -independent pathways without antagonizing host defense signaling. J Virol. 2006;80:2913–2923. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2913-2923.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S, Brzozka K, Jung A, Kato H, Poeck H, Akira S, Conzelmann KK, Schlee M, Endres S, Hartmann G. 5'-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Mikamo-Satoh E, Hirai R, Kawai T, Matsushita K, Hiiragi A, Dermody TS, Fujita T, Akira S. Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goubau D, Schlee M, Deddouche S, Pruijssers AJ, Zillinger T, Goldeck M, Schuberth C, Van der Veen AG, Fujimura T, Rehwinkel J, Iskarpatyoti JA, Barchet W, Ludwig J, Dermody TS, Hartmann G, Reis e Sousa C. Antiviral immunity via RIG-I-mediated recognition of RNA bearing 5'-diphosphates. Nature. 2014;514:372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguirre S, Luthra P, Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Maestre AM, Patel J, Lamothe F, Fredericks AC, Tripathi S, Zhu T, Pintado-Silva J, Webb LG, Bernal-Rubio D, Solovyov A, Greenbaum B, Simon V, Basler CF, Mulder LC, Garcia-Sastre A, Fernandez-Sesma A. Dengue virus NS2B protein targets cGAS for degradation and prevents mitochondrial DNA sensing during infection. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17037. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aguirre S, Maestre AM, Pagni S, Patel JR, Savage T, Gutman D, Maringer K, Bernal-Rubio D, Shabman RS, Simon V, Rodriguez-Madoz JR, Mulder LC, Barber GN, Fernandez-Sesma A. DENV inhibits type I IFN production in infected cells by cleaving human STING. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002934. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu CY, Chang TH, Liang JJ, Chiang RL, Lee YL, Liao CL, Lin YL. Dengue virus targets the adaptor protein MITA to subvert host innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002780. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, Rice CM. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai X, Chiu YH, Chen ZJ. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2014;54:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barber GN. STING-dependent signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:929–930. doi: 10.1038/ni.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleary CM, Donnelly RJ, Soh J, Mariano TM, Pestka S. Knockout and reconstitution of a functional human type I interferon receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18747–18749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Novick D, Cohen B, Rubinstein M. The human interferon alpha/beta receptor: characterization and molecular cloning. Cell. 1994;77:391–400. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stark GR, Darnell JE., Jr The JAK-STAT pathway at twenty. Immunity. 2012;36:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schoggins JW. Interferon-stimulated genes: roles in viral pathogenesis. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;6:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenlund AC, Morales MO, Viviano BL, Yan H, Krolewski J, Schreiber RD. Stat recruitment by tyrosine-phosphorylated cytokine receptors: an ordered reversible affinity-driven process. Immunity. 1995;2:677–687. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heim MH, Kerr IM, Stark GR, Darnell JE., Jr Contribution of STAT SH2 groups to specific interferon signaling by the Jak-STAT pathway. Science. 1995;267:1347–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.7871432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shuai K, Horvath CM, Huang LH, Qureshi SA, Cowburn D, Darnell JE., Jr Interferon activation of the transcription factor Stat91 involves dimerization through SH2-phosphotyrosyl peptide interactions. Cell. 1994;76:821–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shuai K, Stark GR, Kerr IM, Darnell JE., Jr A single phosphotyrosine residue of Stat91 required for gene activation by interferon-gamma. Science. 1993;261:1744–1746. doi: 10.1126/science.7690989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu XY, Kessler DS, Veals SA, Levy DE, Darnell JE., Jr ISGF3, the transcriptional activator induced by interferon alpha, consists of multiple interacting polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8555–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy DE, Kessler DS, Pine R, Darnell JE., Jr Cytoplasmic activation of ISGF3, the positive regulator of interferon-alpha-stimulated transcription, reconstituted in vitro. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1362–1371. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schindler C, Fu XY, Improta T, Aebersold R, Darnell JE., Jr Proteins of transcription factor ISGF-3: one gene encodes the 91-and 84-kDa ISGF-3 proteins that are activated by interferon alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7836–7839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy D, Larner A, Chaudhuri A, Babiss LE, Darnell JE., Jr Interferon-stimulated transcription: isolation of an inducible gene and identification of its regulatory region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:8929–8933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reich N, Evans B, Levy D, Fahey D, Knight E, Jr, Darnell JE., Jr Interferon-induced transcription of a gene encoding a 15-kDa protein depends on an upstream enhancer element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:6394–6398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daffis S, Szretter KJ, Schriewer J, Li J, Youn S, Errett J, Lin TY, Schneller S, Zust R, Dong H, Thiel V, Sen GC, Fensterl V, Klimstra WB, Pierson TC, Buller RM, Gale M, Jr, Shi PY, Diamond MS. 2’-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap evades host restriction by IFIT family members. Nature. 2010;468:452–456. doi: 10.1038/nature09489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hyde JL, Diamond MS. Innate immune restriction and antagonism of viral RNA lacking 2-O methylation. Virology. 2015;479–480:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, Adams DJ, Xavier RJ, Farzan M, Elledge SJ. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim JK, Lisco A, McDermott DH, Huynh L, Ward JM, Johnson B, Johnson H, Pape J, Foster GA, Krysztof D, Follmann D, Stramer SL, Margolis LB, Murphy PM. Genetic variation in OAS1 is a risk factor for initial infection with West Nile virus in man. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000321. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang D, Weidner JM, Qing M, Pan XB, Guo H, Xu C, Zhang X, Birk A, Chang J, Shi PY, Block TM, Guo JT. Identification of five interferon-induced cellular proteins that inhibit west nile virus and dengue virus infections. J Virol. 2010;84:8332–8341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02199-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ho LJ, Wang JJ, Shaio MF, Kao CL, Chang DM, Han SW, Lai JH. Infection of human dendritic cells by dengue virus causes cell maturation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 2001;166:1499–1506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez-Madoz JR, Belicha-Villanueva A, Bernal-Rubio D, Ashour J, Ayllon J, Fernandez-Sesma A. Inhibition of the type I interferon response in human dendritic cells by dengue virus infection requires a catalytically active NS2B3 complex. J Virol. 2010;84:9760–9774. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01051-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun P, Fernandez S, Marovich MA, Palmer DR, Celluzzi CM, Boonnak K, Liang Z, Subramanian H, Porter KR, Sun W, Burgess TH. Functional characterization of ex vivo blood myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells after infection with dengue virus. Virology. 2009;383:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Szretter KJ, Daniels BP, Cho H, Gainey MD, Yokoyama WM, Gale M, Jr, Virgin HW, Klein RS, Sen GC, Diamond MS. 2’-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap by West Nile virus evades ifit1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of host restriction in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gillespie LK, Hoenen A, Morgan G, Mackenzie JM. The endoplasmic reticulum provides the membrane platform for biogenesis of the flavivirus replication complex. J Virol. 2010;84:10438–10447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uchil PD, Satchidanandam V. Architecture of the flaviviral replication complex. Protease, nuclease, and detergents reveal encasement within double-layered membrane compartments. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24388–24398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uchida L, Espada-Murao LA, Takamatsu Y, Okamoto K, Hayasaka D, Yu F, Nabeshima T, Buerano CC, Morita K. The dengue virus conceals double-stranded RNA in the intracellular membrane to escape from an interferon response. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7395. doi: 10.1038/srep07395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Junjhon J, Pennington JG, Edwards TJ, Perera R, Lanman J, Kuhn RJ. Ultrastructural characterization and three-dimensional architecture of replication sites in dengue virus-infected mosquito cells. J Virol. 2014;88:4687–4697. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00118-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miorin L, Maiuri P, Marcello A. Visual detection of Flavivirus RNA in living cells. Methods. 2016;98:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Espada-Murao LA, Morita K. Delayed cytosolic exposure of Japanese encephalitis virus double-stranded RNA impedes interferon activation and enhances viral dissemination in porcine cells. J Virol. 2011;85:6736–6749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00233-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takamatsu Y, Uchida L, Morita K. Delayed IFN response differentiates replication of West Nile virus and Japanese encephalitis virus in human neuroblastoma and glioblastoma cells. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:2194–2199. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chiang C, Gack MU. Post-translational Control of Intracellular Pathogen Sensing Pathways. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gack MU, Albrecht RA, Urano T, Inn KS, Huang IC, Carnero E, Farzan M, Inoue S, Jung JU, Garcia-Sastre A. Influenza A virus NS1 targets the ubiquitin ligase TRIM25 to evade recognition by the host viral RNA sensor RIG-I. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rajsbaum R, Albrecht RA, Wang MK, Maharaj NP, Versteeg GA, Nistal-Villan E, Garcia-Sastre A, Gack MU. Species-specific inhibition of RIG-I ubiquitination and IFN induction by the influenza A virus NS1 protein. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003059. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oshiumi H, Miyashita M, Matsumoto M, Seya T. A distinct role of Riplet-mediated K63-Linked polyubiquitination of the RIG-I repressor domain in human antiviral innate immune responses. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003533. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manokaran G, Finol E, Wang C, Gunaratne J, Bahl J, Ong EZ, Tan HC, Sessions OM, Ward AM, Gubler DJ, Harris E, Garcia-Blanco MA, Ooi EE. Dengue subgenomic RNA binds TRIM25 to inhibit interferon expression for epidemiological fitness. Science. 2015;350:217–221. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Versteeg GA, Rajsbaum R, Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Maestre AM, Valdiviezo J, Shi M, Inn KS, Fernandez-Sesma A, Jung J, Garcia-Sastre A. The E3-ligase TRIM family of proteins regulates signaling pathways triggered by innate immune pattern-recognition receptors. Immunity. 2013;38:384–398. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rajsbaum R, Garcia-Sastre A, Versteeg GA. TRIMmunity: the roles of the TRIM E3-ubiquitin ligase family in innate antiviral immunity. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:1265–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Versteeg GA, Benke S, Garcia-Sastre A, Rajsbaum R. InTRIMsic immunity: Positive and negative regulation of immune signaling by tripartite motif proteins. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25:563–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gack MU, Shin YC, Joo CH, Urano T, Liang C, Sun L, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Chen Z, Inoue S, Jung JU. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature. 2007;446:916–920. doi: 10.1038/nature05732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gack MU, Kirchhofer A, Shin YC, Inn KS, Liang C, Cui S, Myong S, Ha T, Hopfner KP, Jung JU. Roles of RIG-I N-terminal tandem CARD and splice variant in TRIM25-mediated antiviral signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16743–16748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804947105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peisley A, Wu B, Xu H, Chen ZJ, Hur S. Structural basis for ubiquitin-mediated antiviral signal activation by RIG-I. Nature. 2014;509:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature13140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pauli EK, Chan YK, Davis ME, Gableske S, Wang MK, Feister KF, Gack MU. The ubiquitin-specific protease USP15 promotes RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling by deubiquitylating TRIM25. Sci Signal. 2014;7 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004577. ra3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pijlman GP, Funk A, Kondratieva N, Leung J, Torres S, van der Aa L, Liu WJ, Palmenberg AC, Shi PY, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. A highly structured, nuclease-resistant, noncoding RNA produced by flaviviruses is required for pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chapman EG, Costantino DA, Rabe JL, Moon SL, Wilusz J, Nix JC, Kieft JS. The structural basis of pathogenic subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) production. Science. 2014;344:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.1250897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chapman EG, Moon SL, Wilusz J, Kieft JS. RNA structures that resist degradation by Xrn1 produce a pathogenic Dengue virus RNA. Elife. 2014;3:e01892. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schuessler A, Funk A, Lazear HM, Cooper DA, Torres S, Daffis S, Jha BK, Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Hertzog P, Silverman R, Akira S, Barton DJ, Diamond MS, Khromykh AA. West Nile virus noncoding subgenomic RNA contributes to viral evasion of the type I interferon-mediated antiviral response. J Virol. 2012;86:5708–5718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Filomatori CV, Carballeda JM, Villordo SM, Aguirre S, Pallares HM, Maestre AM, Sanchez-Vargas I, Blair CD, Fabri C, Morales MA, Fernandez-Sesma A, Gamarnik AV. Dengue virus genomic variation associated with mosquito adaptation defines the pattern of viral non-coding RNAs and fitness in human cells. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006265. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu HM, Loo YM, Horner SM, Zornetzer GA, Katze MG, Gale M., Jr The mitochondrial targeting chaperone 14-3-3epsilon regulates a RIG-I translocon that mediates membrane association and innate antiviral immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chan YK, Gack MU. A phosphomimetic-based mechanism of dengue virus to antagonize innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:523–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.He Z, Zhu X, Wen W, Yuan J, Hu Y, Chen J, An S, Dong X, Lin C, Yu J, Wu J, Yang Y, Cai J, Li J, Li M. Dengue Virus Subverts Host Innate Immunity by Targeting Adaptor Protein MAVS. J Virol. 2016;90:7219–7230. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00221-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rodriguez-Madoz JR, Bernal-Rubio D, Kaminski D, Boyd K, Fernandez-Sesma A. Dengue virus inhibits the production of type I interferon in primary human dendritic cells. J Virol. 2010;84:4845–4850. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02514-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ablasser A, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hemmerling I, Horvath GL, Schmidt T, Latz E, Hornung V. Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nature. 2013;503:530–534. doi: 10.1038/nature12640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arjona A, Ledizet M, Anthony K, Bonafe N, Modis Y, Town T, Fikrig E. West Nile virus envelope protein inhibits dsRNA-induced innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2007;179:8403–8409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Anglero-Rodriguez YI, Pantoja P, Sariol CA. Dengue virus subverts the interferon induction pathway via NS2B/3 protease-IkappaB kinase epsilon interaction. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:29–38. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00500-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dalrymple NA, Cimica V, Mackow ER. Dengue Virus NS Proteins Inhibit RIG-I/MAVS Signaling by Blocking TBK1/IRF3 Phosphorylation: Dengue Virus Serotype 1 NS4A Is a Unique Interferon-Regulating Virulence Determinant. MBio. 2015;6:e00553–00515. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00553-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu WJ, Chen HB, Wang XJ, Huang H, Khromykh AA. Analysis of adaptive mutations in Kunjin virus replicon RNA reveals a novel role for the flavivirus nonstructural protein NS2A in inhibition of beta interferon promoter-driven transcription. J Virol. 2004;78:12225–12235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12225-12235.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Clark DC, Lobigs M, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. A single amino acid substitution in the West Nile virus nonstructural protein NS2A disables its ability to inhibit alpha/beta interferon induction and attenuates virus virulence in mice. J Virol. 2006;80:2396–2404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2396-2404.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Samuel MA, Diamond MS. Alpha/beta interferon protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by restricting cellular tropism and enhancing neuronal survival. J Virol. 2005;79:13350–13361. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13350-13361.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Keller BC, Fredericksen BL, Samuel MA, Mock RE, Mason PW, Diamond MS, Gale M., Jr Resistance to alpha/beta interferon is a determinant of West Nile virus replication fitness and virulence. J Virol. 2006;80:9424–9434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00768-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shresta S, Kyle JL, Robert Beatty P, Harris E. Early activation of natural killer and B cells in response to primary dengue virus infection in A/J mice. Virology. 2004;319:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ashour J, Morrison J, Laurent-Rolle M, Belicha-Villanueva A, Plumlee CR, Bernal-Rubio D, Williams KL, Harris E, Fernandez-Sesma A, Schindler C, Garcia-Sastre A. Mouse STAT2 restricts early dengue virus replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yauch LE, Shresta S. Mouse models of dengue virus infection and disease. Antiviral Res. 2008;80:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meier KC, Gardner CL, Khoretonenko MV, Klimstra WB, Ryman KD. A mouse model for studying viscerotropic disease caused by yellow fever virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000614. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Erickson AK, Pfeiffer JK. Dynamic viral dissemination in mice infected with yellow fever virus strain 17D. J Virol. 2013;87:12392–12397. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02149-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tripathi S, Balasubramaniam VR, Brown JA, Mena I, Grant A, Bardina SV, Maringer K, Schwarz MC, Maestre AM, Sourisseau M, Albrecht RA, Krammer F, Evans MJ, Fernandez-Sesma A, Lim JK, Garcia-Sastre A. A novel Zika virus mouse model reveals strain specific differences in virus pathogenesis and host inflammatory immune responses. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morrison TE, Diamond MS. Animal Models of Zika Virus Infection, Pathogenesis, and Immunity. J Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00009-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Diamond MS, Roberts TG, Edgil D, Lu B, Ernst J, Harris E. Modulation of Dengue virus infection in human cells by alpha, beta, and gamma interferons. J Virol. 2000;74:4957–4966. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.4957-4966.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin RJ, Liao CL, Lin E, Lin YL. Blocking of the alpha interferon-induced Jak-Stat signaling pathway by Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:9285–9294. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9285-9294.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Best SM, Morris KL, Shannon JG, Robertson SJ, Mitzel DN, Park GS, Boer E, Wolfinbarger JB, Bloom ME. Inhibition of interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling by a tick-borne flavivirus and identification of NS5 as an interferon antagonist. J Virol. 2005;79:12828–12839. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12828-12839.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ho LJ, Hung LF, Weng CY, Wu WL, Chou P, Lin YL, Chang DM, Tai TY, Lai JH. Dengue virus type 2 antagonizes IFN-alpha but not IFN-gamma antiviral effect via down-regulating Tyk2-STAT signaling in the human dendritic cell. J Immunol. 2005;174:8163–8172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kurane I, Innis BL, Nimmannitya S, Nisalak A, Meager A, Ennis FA. High levels of interferon alpha in the sera of children with dengue virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:222–229. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Solomon T, Dung NM, Wills B, Kneen R, Gainsborough M, Diet TV, Thuy TT, Loan HT, Khanh VC, Vaughn DW, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Interferon alfa-2a in Japanese encephalitis: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:821–826. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Munoz-Jordan JL, Sanchez-Burgos GG, Laurent-Rolle M, Garcia-Sastre A. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335168100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Munoz-Jordan JL, Laurent-Rolle M, Ashour J, Martinez-Sobrido L, Ashok M, Lipkin WI, Garcia-Sastre A. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. J Virol. 2005;79:8004–8013. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8004-8013.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Mokhonov VV, Shi PY, Randall R, Khromykh AA. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the New York 99 strain and Kunjin subtype of West Nile virus involves blockage of STAT1 and STAT2 activation by nonstructural proteins. J Virol. 2005;79:1934–1942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1934-1942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ashour J, Laurent-Rolle M, Shi PY, Garcia-Sastre A. NS5 of dengue virus mediates STAT2 binding and degradation. J Virol. 2009;83:5408–5418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02188-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jones M, Davidson A, Hibbert L, Gruenwald P, Schlaak J, Ball S, Foster GR, Jacobs M. Dengue virus inhibits alpha interferon signaling by reducing STAT2 expression. J Virol. 2005;79:5414–5420. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5414-5420.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mazzon M, Jones M, Davidson A, Chain B, Jacobs M. Dengue virus NS5 inhibits interferon-alpha signaling by blocking signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 phosphorylation. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1261–1270. doi: 10.1086/605847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Morrison J, Laurent-Rolle M, Maestre AM, Rajsbaum R, Pisanelli G, Simon V, Mulder LC, Fernandez-Sesma A, Garcia-Sastre A. Dengue virus co-opts UBR4 to degrade STAT2 and antagonize type I interferon signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003265. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Grant A, Ponia SS, Tripathi S, Balasubramaniam V, Miorin L, Sourisseau M, Schwarz MC, Sanchez-Seco MP, Evans MJ, Best SM, Garcia-Sastre A. Zika Virus Targets Human STAT2 to Inhibit Type I Interferon Signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kumar A, Hou S, Airo AM, Limonta D, Mancinelli V, Branton W, Power C, Hobman TC. Zika virus inhibits type-I interferon production and downstream signaling. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1766–1775. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Laurent-Rolle M, Morrison J, Rajsbaum R, Macleod JM, Pisanelli G, Pham A, Ayllon J, Miorin L, Martinez-Romero C, tenOever BR, Garcia-Sastre A. The interferon signaling antagonist function of yellow fever virus NS5 protein is activated by type I interferon. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:314–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lin RJ, Chang BL, Yu HP, Liao CL, Lin YL. Blocking of interferon-induced Jak-Stat signaling by Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 through a protein tyrosine phosphatase-mediated mechanism. J Virol. 2006;80:5908–5918. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02714-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Laurent-Rolle M, Boer EF, Lubick KJ, Wolfinbarger JB, Carmody AB, Rockx B, Liu W, Ashour J, Shupert WL, Holbrook MR, Barrett AD, Mason PW, Bloom ME, Garcia-Sastre A, Khromykh AA, Best SM. The NS5 protein of the virulent West Nile virus NY99 strain is a potent antagonist of type I interferon-mediated JAK-STAT signaling. J Virol. 2010;84:3503–3515. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01161-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Guo JT, Hayashi J, Seeger C. West Nile virus inhibits the signal transduction pathway of alpha interferon. J Virol. 2005;79:1343–1350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1343-1350.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Parton RG. Cholesterol manipulation by West Nile virus perturbs the cellular immune response. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Liang JJ, Liao CL, Liao JT, Lee YL, Lin YL. A Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine candidate strain is attenuated by decreasing its interferon antagonistic ability. Vaccine. 2009;27:2746–2754. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]