Abstract

BACKGROUND

Resilience has been shown to protect against the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the aftermath of trauma. However, it remains unclear how coping strategies influence resilience and PTSD development in the acute aftermath of trauma. The current prospective, longitudinal study investigated the relationship between resilience, coping strategies, and the development of chronic PTSD symptoms.

METHODS

A sample of patients was recruited from an emergency department following a Criterion A trauma. Follow-up assessments were completed at 1-, 3-, and 6-months post-trauma to assess PTSD symptom development (N = 164).

RESULTS

Resilience at 1-month positively correlated with the majority of active coping strategies (all p < .05) and negatively correlated with the majority of avoidant coping strategies (all p < .05), as well as future PTSD symptoms (p < .001). Additionally, all avoidant coping strategies, including social withdrawal, positively correlated with future PTSD symptoms (all p < .01). After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, social withdrawal at 3-months fully mediated the relationship between resilience at 1-month and PTSD symptoms at 6-months.

LIMITATIONS

Limitations include participant drop out and the conceptual overlap between avoidant coping and PTSD.

CONCLUSIONS

These data suggest that resilience and social withdrawal may be possible therapeutic targets for mitigating the development of chronic PTSD in the aftermath of trauma.

Keywords: resilience, CD-RISC, PTSD, coping strategies, social withdrawal

Resilience is the capacity to thrive in the face of adversity. There is no universally accepted definition of resilience, and resilience is conceptualized in different ways: as a trait in which one experiences mild, short-lived distress following trauma (Bonanno, 2004); as good outcomes and competency following adverse events (Masten, 2001); or as a process that involves positive adaptation to adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Meredith, Sherbourne, & Gaillot, 2011). A limitation of the first definition is that it frames resilience as a static trait, which does not allow for an individual’s resilience to grow after facing adversity or to collapse when confronting chronic stress (Meredith et al., 2011). Interpreting resilience as adaptive functioning or competency based on observable behavioral indicators can also be problematic because of the arbitrary categorization of individuals as high or low functioning (Wald, Taylor, Asmundson, Jang, & Stapleton, 2006). In contrast, conceptualizing resilience as the capacity to recover from adverse events and as a dynamic process allows for it to vary with personal characteristics (e.g., age, sex, culture), as well as an individual’s past life experiences and current life circumstances (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Resilience as a dynamic process is malleable over time, in which one can adapt and experience stressful situations (Meredith et al., 2011). This definition of resilience was adopted for the current paper, as it permits one to measure an individual’s resilient characteristics across time and predict their response to adversity and trauma.

High levels of resilience are a key protective factor against adverse outcomes, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Numerous cross-sectional studies have shown that resilient individuals are less likely to develop PTSD symptoms following a traumatic event (Lee, Ahn, Jeong, Chae, & Choi, 2014; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; Wrenn et al., 2011). However, longitudinal designs offer advantages in examining the role of resilience as a predictor in the development of PTSD symptoms after trauma exposure. One of the few prior studies to prospectively measure resilience and PTSD found that lower resilience measured at either 1–2 weeks or 5–6 weeks post-trauma predicted increased PTSD symptom severity at 5–6 weeks and 3-months post-trauma (Daniels et al., 2012). Contrary to these results, low resilience was not predictive of increased PTSD at 3-months post-trauma in another study (Powers et al., 2014). The equivocal nature of these findings could be due to the two studies measuring resilience at different time points, using different measures to diagnose PTSD (structured clinical interview that assessed symptom frequency and intensity versus four-item PTSD screen that categorized patients as either symptomatic or asymptomatic), and the different participant characteristics, as the Daniels et. al. subjects were younger, more likely to be female, and more likely experienced a motor vehicle collision. These divergent findings indicate that more prospective, longitudinal studies of resilience are necessary to understand the capacity of resilience as a predictor of future PTSD symptoms in the aftermath of trauma.

Resilience has been associated with other protective factors, particularly coping skills, in the context of adverse events (Reich, Zautra, & Hall, 2010). Coping is defined as an individual’s use of behavioral and cognitive strategies to modify adverse aspects of their environment, as well as minimize or escape internal threats induced by stress or trauma (Gil, 2005; Weinberg, Gil, & Gilbar, 2014). Coping can be categorized into active and avoidant strategies. Active coping reflects attempts to change perceptions of the stressor or qualities of the stressor (e.g., problem solving and cognitive restructuring). In contrast, avoidant coping involves actions and thought processes used to escape direct confrontation with the stressor (e.g., wishful thinking and social withdrawal) (Wu et al., 2013). Resilient individuals have been found to employ greater amounts of active coping (Feder, Nestler, & Charney, 2009; Li & Nishikawa, 2012) and social support-seeking behaviors (Wu et al., 2013). Despite being closely related and used interchangeably, there is growing consensus that resilience and coping are conceptually distinct constructs (Campbell-Sills, Cohan, & Stein, 2006; Major, Richards, Cooper, Cozzarelli, & Zubek, 1998), such that “resilience influences how an event is appraised, whereas coping refers to the strategies employed following the appraisal of a stressful encounter” (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013). Furthermore, resilience is a set of protective factors (e.g. close relationships with family and community, optimistic outlook, embracing challenges) that allows an individual to have a positive response to adverse events, while coping strategies may yield either positive or negative results (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Meredith et al., 2011). For the current study, we focused on coping strategies rather than coping styles given the evidence that coping strategies mediate the relationship between resilience and outcomes (Major et al., 1998), in contrast to coping styles which may function instead “as a resilient protective factor that moderate components of the stress process” (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006).

Coping strategies influence PTSD development. Avoidant coping is linked to increased PTSD symptom development following trauma (Gil, 2005; Hooberman, Rosenfeld, Rasmussen, & Keller, 2010), possibly “because denying the severity of a problem and trying not to think about it may lead to more recurrent and intrusive recollections of the trauma” (Tiet et al., 2006). The relationship between active coping strategies and PTSD has been equivocal (Alim et al., 2008; Gil, 2005; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Wright, Crawford, & Sebastian, 2007). Given the strong relationship between resilience and coping, resilience may influence coping strategy selection, which may in turn impact the development of PTSD symptoms. To our knowledge, no one has investigated whether coping strategies mediate the relationship between resilience and PTSD symptom development in a longitudinal, prospective study. Thus, we investigated the role of resilience and coping strategies measured 1-month post-trauma and 3-months post-trauma, respectively, in the development of PTSD symptoms 6-months post-trauma. We measured resilience, coping, and PTSD symptoms at separate time points in order to establish temporal precedence for a prospective mediation model (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). We hypothesized that individuals with high levels of resilience at 1-month posttrauma would be more likely to use active coping strategies, less likely to employ avoidant coping strategies, and less likely to develop PTSD symptoms at 6-months following trauma exposure. We also hypothesized that 3-month coping strategies would mediate the relationship between resilience at 1-month post-trauma and PTSD severity at 6-months post-trauma.

Methods

Procedures

Participants were recruited in the Emergency Department of an inner city level-1 trauma center (offering comprehensive service to patients) and provided informed consent. Patients were included in the study if they were between the ages of 18 and 65, were English-speaking, were alert and oriented, and endorsed criterion A trauma (experienced, witnessed, or were confronted with an event that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of the patient or others) consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric & American Psychiatric, 2000). Exclusion criteria included recent or current suicidality, active psychosis, or significant substance use during screening (determined by a positive toxicology report found in electronic medical chart). An initial assessment was completed at the Emergency Department within a few hours of the trauma. Follow-up assessments of measures (described below) were completed in person at 1-month, 3-months, and 6-months post-trauma. Assessors trained by clinical psychologists to administer measures outlined below completed all study assessments. Inter-rater reliability was 97%. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and the Grady Hospital Research Oversight Committee.

Measures

The Standardized Trauma Interview was administered at baseline in the Emergency Department to gather information about demographic variables and characteristics of the index trauma, such as the extent of injuries sustained, subjective experience of hopelessness and helplessness during the traumatic event, and patient-rated severity of trauma with a scale of 1 (not life-threatening) to 5 (near-death experience) (Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992). The STI is a semi-structured interview modified from the Standardized Assault Interview (SAI; Rothbaum et al., 1992) that has been used previously (Rothbaum et al., 2006).

Resilience was measured at 1-month post-trauma with the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, 2003). The CD-RISC is a 25-item scale that assesses one’s ability to cope with adversity and stress during the past month (e.g. able to adapt to change, have close and secure relationships, belief one can deal with whatever comes and having control of one’s life). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not true at all to true nearly all the time. CD-RISC scores can change with time, clinical improvement, and treatment, and the scale has adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Total CD-RISC scores representative of resilience were utilized for this study (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Coping strategies were assessed at 3-months post-trauma using the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI; Tobin, Holroyd, Reynolds, & Wigal, 1989), which has strong psychometric properties (Cook & Heppner, 1997; Tobin, Holroyd, Reynolds, & Wigal, 1989). The CSI is a 72-item self-report measure that assesses coping thoughts and behaviors tied to a specific event (in this case, the occurrence of a Criterion A trauma for which individuals where enrolled in study). Respondents are asked to indicate to what extent they used each particular coping response using a 5-item Likert rating scale, ranging from none to very much. Eight primary scales are included in the CSI including Problem Solving, Cognitive Restructuring, Social Support, Expressing Emotions, Problem Avoidance, Wishful Thinking, Self-Criticism, and Social Withdrawal. Seven of the eight CSI scales had Cronbach’s α values above .70, except for problem avoidance (α = .64).

PTSD symptoms were assessed at 6-months post-trauma with the PTSD Symptom Scale (Edna B Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993). The PSS is a semi-structured interview consisting of 17 items that measures the presence and severity of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms. Symptoms were assessed in relation to the past month, with ratings reflecting a combination of frequency and severity, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (5 or more times per week/very much). The PSS has excellent psychometric properties with moderate to high agreement with the DSM -IV Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale as well as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Past traumatization, childhood trauma in particular, is an important predictor of PTSD symptoms following trauma (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). Thus, we assessed for childhood trauma in the Emergency Department using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein, 1995). The CTQ is a 28-item self-report measure that quantifies the amount and types of childhood trauma (physical, sexual, emotional abuse and neglect) experienced and has been shown have adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Bernstein et al., 1994).

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS (v.20) and alpha level was set at p < .05. The clinical and demographic characteristics of participants and differences between dropouts and non drop-outs were assessed using descriptive statistics, chi-square, and t-tests. The relationship of demographic and clinical variables with resilience and PTSD symptoms were determined with ANOVAs and bivariate correlations. Associations between the seven demographic and clinical variables with both resilience and PTSD symptoms were considered significant at a p ≤ .007 after Bonferonni correcting to account for multiple testing. The associations between resilience, coping strategies, and future PTSD symptoms were examined with bivariate correlation analyses. These variables were measured at 1-month, 3-month, or 6-month interviews, respectively; thus, participants that dropped out before attending the 6-month interview were not included in this test or subsequent analyses. Missing data due to missed appointments at 1- and 3-months were imputed with the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) analysis (Arbuckle & Wothke, 2004; Wothke, Little, Schnabel, & Baumert). Effect sizes for all null hypotheses were assessed using Pearson’s coefficient and partial-eta squared.

Coping strategies that significantly correlated with both CD-RISC and PSS scores were analyzed individually as mediators in the relationship between resilience and PTSD symptoms. Mediation analyses were performed using the indirect methods of SPSS (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) that allows for the examination of mediating effects of a variable while controlling for the effects of other factors in the model. Normality of the variables were checked and mediation analyses were carried out using 5000 bootstrap samples and bias-corrected methods to assess indirect effects of 3-month coping strategies on the total effect of 1-month resilience on PTSD symptoms at 6-months, as this method is preferred for interpreting mediation analyses (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The total effect is the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable in the absence of the mediator, while the direct effect is the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable when the mediator is accounted for. The indirect effect is the amount of mediation accounted for by the mediating variable. The significance of the mediator (indirect effect) was determined by assessing the 95% confidence interval (CI) related to the sampling distribution of the mean, with confidence intervals that did not include zero considered as being statistically significant. Mediation analyses were repeated for coping strategies found to have significant indirect effects, controlling for demographic and clinical variables that were previously associated with CD-RISC and/or PSS scores (specifically, gender, education, patient-rated severity, interpersonal violence, and childhood trauma). A full mediation was determined when the direct effect of resilience on PTSD symptoms became insignificant in the presence of the mediator.

Results

Participants

Socio-demographic information and clinical variables for adults who participated in the Emergency Department assessment are presented in Table 1. The following number of persons participated in each assessment: 341 individuals were recruited into the study and underwent an interview in the Emergency Department; 220 attended the 1-month follow-up interview; 195 attended the 3-month follow-up interview; and 164 completed the 6-month follow-up interview. As we included participants who attended their 6-month follow-up interview, 164 participants were included in our analyses. The breakdown for types of trauma were classified as follows: 57.9% motor vehicle crashes; 9.1% pedestrians vs. automobiles; 6.7% non-sexual assaults; 5.5% falls; 4.9% sexual assaults; 3.7% motorcycle accidents; 3.7% industrial/home accidents; 3.0% bike accidents; 2.4% stabbing; and the remaining 3.1% were gun shot wounds, fire/burns, or ‘other’. The mean score on the CTQ in the current study (M = 39.36, SD = 17.08) was significantly higher compared to the mean CTQ score previously found in a normative community sample (M = 31.71, SD = 9.13 for men, M = 31.77, SD = 11.20 for women; p < .001) (Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary, & Forde, 2001). The mean CD-RISC score for this sample at 1-month after FIML analysis was 80.72 (SD = 11.76), which is similar to the mean CD-RISC score of the normative general population sample (Connor & Davidson, 2003).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical variables associated with 1-month resilience and 6-month PTSD symptoms.

| Demographics/Clinical Variables | % of Participants | η2, Mean ± SD for CD-RISC score at 1-month | η2, Mean ± SD for PSS score at 6-months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 55.5 | .03, 81.32 ± 10.67 | .06, 8.51 ± 9.95* | |

| Female | 44.5 | 79.98 ± 13.03 | 14.16 ± 11.74 | |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| African American/Black | 73.6 | .03, 81.74 ± 12.53 | .07, 11.98 ± 11.12 | |

| White | 17.8 | 76.91 ± 8.74 | 8.03 ± 10.12 | |

| Mixed | 4.3 | 82.54 ± 6.26 | 10.29 ± 15.77 | |

| Asian | 1.8 | 82.47 ± 11.50 | 3.67 ± 6.35 | |

| Other | 2.5 | 74.85 ± 12.41 | 13.5 ± 9.68 | |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| <12th Grade | 13.4 | .03, 75.96 ± 13.26 | .09, 17.32 ± 12.59* | |

| 12th or High School Grad | 26.8 | 80.21 ± 14.00 | 12.80 ± 12.01 | |

| Some College or Technical School |

36.6 | 81.28 ± 9.48 | 10.27 ± 10.34 | |

| Graduated from College or Higher |

23.2 | 83.20 ± 10.85 | 6.53 ± 8.17 | |

|

| ||||

| Monthly Income | ||||

| $0 – 499 | 10.1 | .01, 80.75 ± 12.73 | .05, 9.06 ± 7.77 | |

| $500 – 999 | 18.4 | 78.78 ± 14.02 | 15.34 ± 12.49 | |

| $1000 – 1999 | 20.3 | 80.14 ± 10.64 | 12.19 ± 10.96 | |

| $2000 or more | 51.3 | 81.98 ± 11.52 | 9.27 ± 10.65 | |

|

| ||||

| Interpersonal Violence | ||||

| Yes | 14.6 | .01, 78.14 ± 11.29 | .06, 17.67 ± 10.66* | |

| No | 85.4 | 81.17 ± 11.82 | 9.89 ± 10.82 | |

|

| ||||

| r | r | |||

| Age | N/A | .03 | .05 | |

| Patient-rated Trauma Severity |

N/A | −.06 | .27* | |

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire |

N/A | −.18 | .30* | |

p ≤ 0.007.

r is the Pearson Correlation Coefficient. η2 is partial eta squared. N = 164.

No clinical or demographic variables were associated with resilience (Table 1). Participants with elevated levels of PTSD symptoms at 6 months were more likely to have less education (p = .002), have a higher self-rated trauma severity (p < .001), have more childhood trauma (p < .001), have experienced interpersonal violence in the index trauma (p = .001), and be female (p = .001). Other socio-demographic variables were not significantly associated with PTSD symptoms (Table 1). No clinical or demographic variables were associated with study drop out after adjusting for multiple comparisons (data not shown).

Resilience at 1-month, Coping at 3-months, and PTSD Symptoms at 6-months

The relationships between resilience at 1-month, coping strategies at 3-months, and PTSD symptoms at 6-months are presented in Table 2. Resilience positively correlated with the coping strategies problem solving (p < .05), cognitive restructuring (p < .05), and social support (p < .01), and negatively associated with the coping strategies wishful thinking (p < .05), self-criticism (p < .05), and social withdrawal (p < .001), as well as PTSD symptoms (p < .001). Most of the coping strategies positively correlated with other coping strategies (see Table 2). Of the eight coping strategies examined, individuals who used problem solving (p < .05), expressing emotions (p < .01), problem avoidance (p < .001), wishful thinking (p < .001), self-criticism (p < .01), and social withdrawal (p < .001) as coping strategies at 3-months had higher PTSD symptoms at 6-months.

Table 2.

The relationships between resilience at 1-month, coping strategies at 3-months, and PTSD symptoms at 6-months.

| 1) | 2) | 3) | 4) | 5) | 6) | 7) | 8) | 9) | 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) CD–RISC | 1 | .15* | .17* | .10 | .24** | −.12 | −.16* | −.19* | −.30*** | −.29*** |

| 2) CSI: Problem Solving | .15* | 1 | .61*** | .52*** | .33** | .27*** | .37*** | .15 | .20* | .16* |

| 3) CSI: Cognitive Restructuring | .17* | .61*** | 1 | .58*** | .50*** | .37** | 36* | .10 | .10 | .07 |

| 4) CSI: Express Emotions | .10 | .52*** | .58*** | 1 | .58*** | .47** | .49*** | .25** | .21** | .25** |

| 5) CSI: Social Support | 24** | .33*** | .50*** | .58*** | 1 | .24** | .20* | .05 | −.20** | −.01 |

| 6) CSI: Problem Avoidance | −.16* | .37*** | .36* | .49*** | .22** | 1 | .47*** | .39*** | .46* | .37* |

| 7) CSI: Wishful Thinking | −.19 | .32** | .27* | .45*** | .20* | .47*** | 1 | .33*** | .48*** | .51*** |

| 8) CSI: Self Criticism | −.19* | .15 | .10 | .25** | .05 | .39*** | .33*** | 1 | .38*** | .23** |

| 9) CSI: Social Withdrawal | −.30*** | .20* | .10 | .21** | −.20** | .46*** | .48*** | .38** | 1 | .54*** |

| 10) PSS Score | −.29*** | .16* | .07 | .25** | −.01 | .37*** | .51*** | .23** | .54*** | 1 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Pearson correlation between the above variables. CD-RISC: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. CSI: Coping Strategies Inventory. PSS: Post-traumatic Stress Inventory. N = 164.

Mediation Model

Problem solving, wishful thinking, self-criticism, and social withdrawal were coping strategies at 3-months that related to both resilience at 1 month and PTSD symptoms at 6-months. These variables were examined as mediators in further analyses.

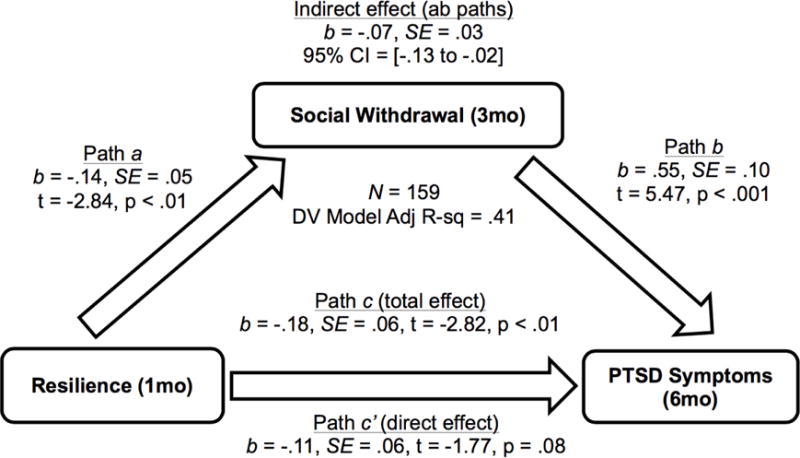

Resilience was negatively associated with both social withdrawal [b(SE) = −.19 (.05); p < .001] and PTSD symptoms [b(SE) = −.27 (.07); p < .001]. When both social withdrawal and resilience were entered into the model, the bootstrap test indicated the indirect effect of social withdrawal on increased PTSD symptoms at 6-months was significant [CI (−0.22, −0.06)]. When controlling for education, patient rated severity, gender, interpersonal violence, and childhood trauma, resilience was still negatively related to social withdrawal [b(SE) = −.14 (.05); p < .01] and PTSD symptoms [b(SE) = −.18 (.06); p < .01], and social withdrawal was positively associated with PTSD symptoms [b(SE) = .55 (.10); p < .001]. The bootstrap test indicated that the indirect effect of social withdrawal on PTSD symptoms at 6-months was still significant [CI (−.13, −.02)]. The direct effect of resilience on PTSD was no longer significant (p = .08), indicating that social withdrawal fully mediated the relationship between resilience and PTSD symptoms after controlling for covariates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The full mediating effect of social withdrawal at 3-months on the relationship between resilience at 1-month and PTSD symptom development at 6-months post-trauma, after controlling for demographic and clinical variables. Path a shows the significant association between the dependent variable (resilience) and the mediator (social withdrawal). Path b shows the significant association between the mediator (social withdrawal) and the independent variable (PTSD symptoms). Path c depicts the significant association (total effect) between the dependent variable (resilience) and the independent variable (PTSD symptoms) in the absence of the mediator (social withdrawal). Path c′ shows the direct effect of the dependent variable (resilience) on the independent variable (PTSD symptoms) when the mediator (social withdrawal) is accounted for. Path ab shows the indirect effect, the amount of mediation accounted for by the mediating variable.

When examined individually, problem solving, wishful thinking, and selfcriticism at 3 months were not significant mediators between resilience at 1 month and PTSD symptoms at 6 months after controlling for covariates. The bootstrap tests indicated the indirect effects of the coping strategies problem solving [CI (.00, .08)]; wishful thinking [CI (−.09, .01)]; and self-criticism [CI (−.10, .00)] on PTSD symptoms were not significant, as the confidence intervals included zero.

Discussion

The present prospective study found that higher resilience at 1-month post-trauma was associated with lower PTSD symptoms 6-months post-trauma, which is consistent with prior prospective findings (Daniels et al., 2012) and retrospective studies (Lee et al., 2014; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; Wrenn et al., 2011). The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to show that early resilience can predict PTSD symptom development as late as 6-months post-trauma. Our results stand in contrast to Powers et al., who found that resilience did not predict PTSD longitudinally (Powers et al., 2014). Inconsistencies in findings could be due to discrepancies in time points when resilience was measured, differences in whether PTSD symptoms or diagnosis were used as the outcome variable of interest, and dissimilarity in patient samples. Additionally, the current study primarily included African American inner-city participants, who often have higher exposure to trauma compared to the general population (Breslau et al., 1998).

Resilience was predictive of increased social support, an active coping strategy, and inversely related to social withdrawal, an avoidant coping strategy. This finding corroborates past studies that have found robust associations between resilience and social support, as well as social-support seeking behaviors (Feder et al., 2009; Ni, Chow, Jiang, Li, & Pang, 2015; Wu et al., 2013). There was also a positive relationship between resilience and most other active coping strategies and a negative relationship between resilience and most other avoidant coping strategies, which is consistent with the current study’s hypothesis and previous findings (Feder et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2013). One hypothesis for this relationship is that resilient individuals are more capable of facing their fears, exhibiting low levels of denial, experiencing positive emotions, and exhibiting social competence, all of which allows them to actively cope with stress (Feder et al., 2009).

All avoidant coping strategies were positively associated with PTSD symptom development in the current study. Both retrospective and prospective studies have found that avoidant coping increases vulnerability for PTSD (Gil, 2005; Hooberman et al., 2010; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009). One hypothesis for this relationship is that individuals who employ avoidant coping strategies following a trauma fail to appropriately process their fear responses, which can lead to the continuation of PTSD symptoms (Edna B. Foa & Riggs, 1995; Tiet et al.). Additionally, the lack of social support experienced by those who engage in social withdrawal may increase vulnerability to PTSD in the aftermath of trauma, as social support is a protective factor against PTSD (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008; Connor & Davidson, 2003; Pietrzak et al., 2010; Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley, & Southwick, 2009).

Intriguingly, half of the active coping strategies (problem solving and expressing emotions) were associated with greater PTSD symptom development in the current study, while other active coping strategies had no relationship with PTSD symptoms. These results are not surprising given previous equivocal findings (Alim et al., 2008; Gil, 2005; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Wright et al., 2007). Evidence suggests that within active coping, emotion-focused coping can lead to greater PTSD (Gil, 2005), which could explain why in the present study expressing emotions was positively associated with PTSD. However, it is surprising that social support, also an emotion-focused coping strategy, did not correlate with PTSD symptom development in this study, as other studies have found strong associations between the two (Brewin et al., 2000; Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008). This inconsistency may be due to assessment of the use of social support-seeking strategies in the current study, which differs from other studies that have investigated individuals’ perceptions of their social support, rather than their use of coping strategies that promote social support. Future investigation is needed to determine the relationship between active coping strategies, specifically social support, and the development of PTSD symptoms following trauma exposure.

Social withdrawal at 3-months post-trauma fully mediated the relationship between resilience at 1-month and PTSD symptoms at 6-months. This result indicates that individuals with lower resilience use high levels of social withdrawal to cope in the aftermath of trauma, thus increasing their risk for developing PTSD symptoms. These findings have important implications for treatment and prevention of PTSD. Low resilience and avoidant coping may be markers of vulnerability to PTSD, which if assessed post-trauma, could identify individuals most likely to benefit from early interventions that target resilience or social withdrawal. Thus, it may be important to boost resilience in trauma-exposed individuals. Interventions that target social withdrawal for individuals with depression exist (Erickson & Hellerstein, 2011) and could be adapted for PTSD prevention in ED settings. Indeed, early interventions administered in the ED following trauma attenuate risk for PTSD (Rothbaum et al., 2012) and could be used in tandem with other methods that bolster resilience in trauma survivors (Macedo et al., 2014; Meredith et al., 2011). On an individual level, individuals can be taught to increase active problem-focused coping, particularly by engaging in cognitive reappraisal. Cognitive reappraisal is relevant to enhancing positive coping, positive affect, positive thinking, and realism, all individual level factors that have been linked to increased resilience (Meredith et al., 2011). Behavioral control, yet another individual level factor linked to resilience, can also be strengthened through training and transfer of skills. Stress inoculation training is an example of a training that enhances resilience by combining some of these elements, and does so by focusing on an individual’s appraisal of their ability to cope with environmental demands and stressors (Meichenbaum & Deffenbacher, 1988). Such training focuses on a conceptual and educational phase, and a skill acquisition and rehearsal phase, where coping skills such as problem solving, relaxation training, and cognitive restructuring are taught, followed by a practice phase where practice of coping skills take place in situations that are progressively challenging.

Strengths of the current study include the prospective design that allowed for the assessment of the directionality between variables. Additionally, our assessments of PTSD symptoms were conducted using semi-structured interview methods rather than self-report. The study sample comprised primarily of inner-city African Americans, providing insight into the resilience and coping strategies of an ethnically under-studied population. While this could be considered a limitation, African Americans are more at risk for trauma exposure than the general population (Breslau et al., 1998), which underscores the importance of studying PTSD in this group. Participant dropout from the time of recruitment in the ED to the 6-month follow-up assessment is also a limitation, as it may be a form of sampling bias and restricts the generalizability of the findings to individuals who come back for longitudinal assessment. Another limitation is that the current study did not fully take into account that early PTSD symptoms in the aftermath of trauma may predict the development of future avoidant coping (Gutner, Rizvi, Monson, & Resick, 2006). Additionally, the inherent conceptual overlap between avoidant coping strategies and PTSD, particularly avoidant PTSD symptoms, may have limited our ability to uniquely measure these constructs as the current study did not remove avoidant PTSD symptoms from our analyses. However, avoidant coping strategies have been found to be distinct from PTSD and actually predict better response to exposure-based treatments in chronic PTSD (Leiner, Kearns, Jackson, Astin, & Rothbaum, 2012). Continued efforts towards understanding specific ways in which resilience relates to PTSD development are needed. Prospective studies with larger sample sizes that look at the development of PTSD symptoms longitudinally are necessary to replicate and extend the current results.

Highlights.

Prospective investigation of resilience, coping strategies, and PTSD development

Recruitment from an emergency department following a Criterion A trauma

Resilience negatively correlated with future PTSD symptoms

Avoidant coping strategies positively correlated with future PTSD symptoms

Social withdrawal mediated association between resilience and future PTSD symptoms

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alex Rothbaum, Thomas Crow, and Becky Roffman for their support and assistance. All of this work would not have been possible without the support of all the nurses, physicians, associate providers, and staff of the Emergency Care Center at Grady Memorial Hospital. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the patients and families that agreed to participate in both studies. The National Institutes of Health supported this work via MH094757 (KJR) and HD085850 (VM).

Role of Funding:

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Authors Thompson Fiorillo, Ressler, Rothbuam and Michopoulos all implemented the overall study design and recruitment of participants. Authors Thompson, Fiorillo, and Michopoulos collected data for the current study and undertook the data analysis. Authors Thompson and Fiorillo wrote first draft of the manuscript, to which all other authors provided feedback on interpretation and presentation.

References

- Alim TN, Feder A, Graves RE, Wang Y, Weaver J, Westphal M, Charney DS. Trauma, Resilience, and Recovery in a High-Risk African-American Population. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1566–1575. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric, A & American Psychiatric, A. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 Users Guide, 1999. Kline Rex B., Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling NY, London 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (53-item version) scoring form. New York: Mount Sinai School of Medicine 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB. Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(4):585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charuvastra A, Cloitre M. Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:301–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(4):558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SW, Heppner PP. A psychometric study of three coping measures. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1997;57(6):906–923. doi: 10.1177/0013164497057006002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels JK, Hegadoren KM, Coupland NJ, Rowe BH, Densmore M, Neufeld RW, Lanius RA. Neural correlates and predictive power of trait resilience in an acutely traumatized sample: a pilot investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73(3):327–332. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson G, Hellerstein DJ. Behavioral activation therapy for remediating persistent social deficits in medication-responsive chronic depression. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2011;17(3):161–169. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000398409.21374.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder A, Nestler EJ, Charney DS. Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(6):446–457. doi: 10.1038/nrn2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience. European Psychologist. 2013 doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Following Assault: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Findings. Current Directions in Psychological Science (Wiley-Blackwell) 1995;4(2):61–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10771786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6(4):459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Gil S. Coping style in predicting posttraumatic stress disorder among Israeli students. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 2005;18(4):351–359. doi: 10.1080/10615800500392732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutner CA, Rizvi SL, Monson CM, Resick PA. Changes in coping strategies, relationship to the perpetrator, and posttraumatic distress in female crime victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(6):813–823. doi: 10.1002/jts.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooberman J, Rosenfeld B, Rasmussen A, Keller A. Resilience in traumaexposed refugees: the moderating effect of coping style on resilience variables. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(4):557–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Ahn YS, Jeong KS, Chae JH, Choi KS. Resilience buffers the impact of traumatic events on the development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;162:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiner AS, Kearns MC, Jackson JL, Astin MC, Rothbaum BO. Avoidant coping and treatment outcome in rape-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(2):317–321. doi: 10.1037/a0026814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MH, Nishikawa T. The relationship between active coping and trait resilience across U.S. And Taiwanese college student samples. Journal of College Counseling. 2012;15(2):157–171. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00013.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo T, Wilheim L, Gonçalves R, Coutinho ESF, Vilete L, Figueira I, Ventura P. Building resilience for future adversity: a systematic review of interventions in non-clinical samples of adults. BioMed Central Psychiatry. 2014;14:227. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0227-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Richards C, Cooper ML, Cozzarelli C, Zubek J. Personal resilience, cognitive appraisals, and coping: an integrative model of adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(3):735. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):227. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum DH, Deffenbacher JL. Stress inoculation training. The Counseling Psychologist. 1988;16(1):69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Sherbourne CD, Gaillot SJ. Promoting psychological resilience in the US military. Rand Corporation; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. PTSD symptoms and self-rated recovery among adult sexual assault survivors: The effects of traumatic life events and psychosocial variables. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33(1):43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01473.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C, Chow MC, Jiang X, Li S, Pang SM. Factors associated with resilience of adult survivors five years after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Symptoms in Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(1):52. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Morgan CA, Southwick SM. Psychosocial buffers of traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, and psychosocial difficulties in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom: The role of resilience, unit support, and postdeployment social support. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;120(1–3):188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015. doi: http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM. Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(8):745–751. doi: 10.1002/da.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Warren AM, Rosenfield D, Roden-Foreman K, Bennett M, Reynolds MC, Smits JA. Predictors of PTSD symptoms in adults admitted to a Level I trauma center: a prospective analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(3):301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Hall JSE. Handbook of adult resilience. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Cahill SP, Foa EB, Davidson JR, Compton J, Connor KM, Hahn CG. Augmentation of sertraline with prolonged exposure in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(5):625–638. doi: 10.1002/jts.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, Walsh W. A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5(3):455–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00977239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Kearns MC, Price M, Malcoun E, Davis M, Ressler KJ, Houry D. Early intervention may prevent the development of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized pilot civilian study with modified prolonged exposure. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(11):957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Stein MB, Asmundson GJ, McCreary DR, Forde DR. The childhood trauma questionnaire in a community sample: psychometric properties and normative data. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(4):843–857. doi: 10.1023/a:1013058625719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiet QQ, Rosen C, Cavella S, Moos RH, Finney JW, Yesavage J. Coping, symptoms, and functioning outcomes of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(6):799–811. doi: 10.1002/jts.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin DL, Holroyd KA, Reynolds RV, Wigal JK. The hierarchical factor structure of the coping strategies inventory. Cognitive therapy and research. 1989;13(4):343–361. doi: 10.1007/BF01173478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(2):320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald J, Taylor S, Asmundson GJ, Jang KL, Stapleton J. Literature review of concepts: Psychological resiliency: DTIC Document 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg M, Gil S, Gilbar O. Forgiveness, coping, and terrorism: do tendency to forgive and coping strategies associate with the level of posttraumatic symptoms of injured victims of terror attacks? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70(7):693–703. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W, Little T, Schnabel K, Baumert J. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. Longitudinal and multi-group modeling with missing data. [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn GL, Wingo AP, Moore R, Pelletier T, Gutman AR, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. The Effect of Resilience on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Trauma-Exposed Inner-City Primary Care Patients. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103(7):560–566. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30381-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M, Crawford E, Sebastian K. Positive Resolution of Childhood Sexual Abuse Experiences: The Role of Coping, Benefit-Finding and MeaningMaking. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22(7):597–608. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9111-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Feder A, Cohen H, Kim JJ, Calderon S, Charney DS, Mathe AA. Understanding resilience. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2013;7:10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]