Abstract

Systems capable of precise motion in the vasculature can offer exciting possibilities for applications in targeted therapeutics and non-invasive surgery. So far, the majority of the work analysed propulsion in a two-dimensional setting with limited controllability near boundaries. Here we show bio-inspired rolling motion by introducing superparamagnetic particles in magnetic and acoustic fields, inspired by a neutrophil rolling on a wall. The particles self-assemble due to dipole–dipole interaction in the presence of a rotating magnetic field. The aggregate migrates towards the wall of the channel due to the radiation force of an acoustic field. By combining both fields, we achieved a rolling-type motion along the boundaries. The use of both acoustic and magnetic fields has matured in clinical settings. The combination of both fields is capable of overcoming the limitations encountered by single actuation techniques. We believe our method will have far-reaching implications in targeted therapeutics.

Devising effective swimming and propulsion strategies in microenvironments is attractive for drug delivery applications. Here Ahmed et al. demonstrate a micropropulsion strategy in which a combination of magnetic and acoustic fields is used to assemble and propel colloidal particles along channel walls.

Introduction

The design parameters of motion at the microscale are distinctly different from their inertia-dominated counterparts1. Nature’s microswimmers, such as bacteria2, spermatozoa3, 4 and volvox5, have evolved to overcome swimming limitations in viscous liquids at low Reynolds numbers. These swimmers adhere to Purcell’s scallop theorem, which states that a swimmer undergoing reciprocal motion will achieve no net movement1, 6. To date, most synthetic swimmers adopt Purcell’s scallop formulation as a design paradigm for propulsion. Existing microswimmers and nanoswimmers are actuated using different mechanisms such as by chemical fuel7–14 or electric fields15, 16, light-induced17–19 and magnetically powered20–22 and they seem promising in a biological or biomedical context23. A major objective that we have for artificial microswimmers and nanoswimmers is that they act as drug carriers in the human body, which requires that they have the ability to be propelled in confined boundaries, such as the vasculature. However, limited work exists regarding propulsion within microchannels or in a confined geometry. Both acoustically24–31 and magnetically powered microswimmers can potentially be used in the human body. However, the motion of acoustic-based swimmers may be adversely affected when they are confined in channels due to swimmer–wall interactions, i.e. secondary acoustic forces may lead to trapping the swimmers at the walls.

Recently, Tasci et al.20 demonstrated magnetic particles that had a rolling-type motion. The described motion was limited to horizontal surfaces because their propulsion mechanism relied on a contact force that inherently depended on the gravitational weight of the particles. Magnetically induced rolling motion of micro-objects in three-dimensional (3D) geometries is challenging because navigation requires the rotational axis of the magnetic field be at a precise angle with respect to the contact boundary. Continuous use of the reaction force will require constant monitoring and precise tracking of the swimmer and corresponding adjustments of the field. In addition, particles that are immersed in liquid experience buoyancy, which acts in opposite directions to the weight, thus minimise the effect of gravity.

We have developed a propulsive mechanism based on combined acoustic and magnetic actuation. To demonstrate rolling motion, micro-sized superparamagnetic particles are injected into the channel, after which a rotating magnetic field is applied. The particles assemble into aggregates due to magnetic interactions. As soon as the acoustic field is activated, the collected particles migrate to the boundary, and a subsequent rolling motion is achieved along the vessel wall. An important feature of our system is the possibility to controlling the normal force, critical for rolling, can be regulated by an acoustic field. We have demonstrated rolling motion along the walls of rectangular and circular microchannels.

Results

Particle motion in an acoustic field

High-frequency acoustic fields at moderate levels of pressure are safe, non-invasive and inexpensive, and they are used extensively in clinical diagnostics and therapeutics. Ultrasound also has been utilised in numerous biotechnological and biomedical applications, such as microfluidic-based micromixers32–34 and chemical gradient generation35, 36, particle/cell manipulation37–45, separation of circulating tumour cells46, the formation of spheroids47, levitation of objects41 and high-resolution imaging48. Contrast agents, such as microbubbles, have been used to enhance the visibility of vessels in ultrasound-based imaging48, 49. Recently, microbubbles in conjunction with ultrasound have been used in the treatment of brain disease50 and gastrointestinal pathology51. Extensive literature exists regarding the behaviour of microbubbles near boundaries52–54 and in vasculatures55 in an acoustic field, but little work has been done on the interactions of solid particles near boundaries.

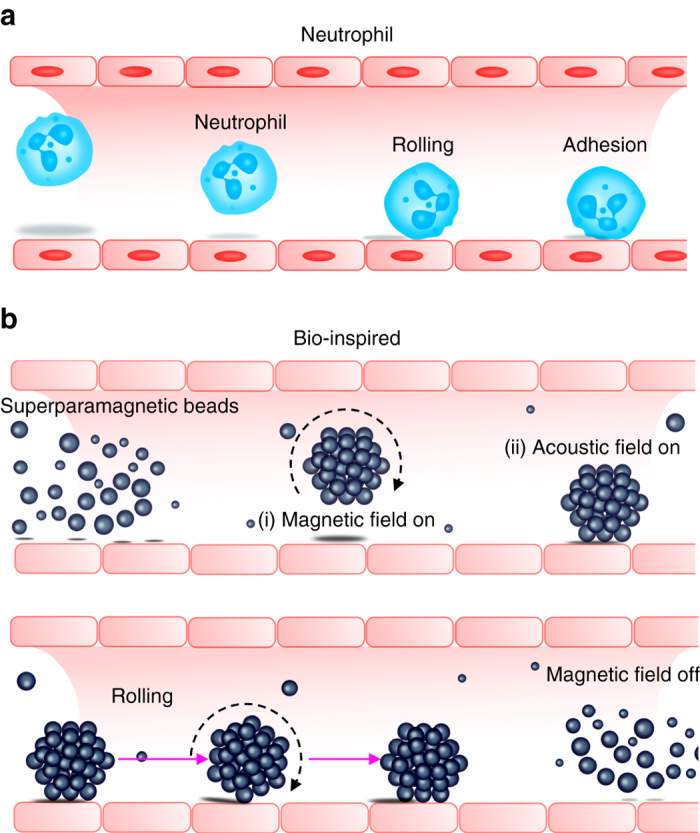

Inspired by neutrophils rolling on endovascular walls before transmigrating to a disease site, we have developed a propulsive mechanism based on combined acoustic and magnetic actuation (Fig. 1a). Rolling motion is demonstrated by introducing superparamagnetic microparticles into the channel, after which a rotating magnetic field is applied. The particles form aggregates due to dipole–dipole interactions (Fig. 1b). The assembled particles migrate to the boundary in an acoustic field when activated at an appropriate frequency, which resulted in a rolling motion along the vessel wall, as shown in Fig. 1b. When the magnetic field is turned off, the assembled entities disassociate.

Fig. 1.

Neutrophil-inspired propulsion based on acoustic and magnetic field actuation. a Neutrophil rolls on vasculature before transmigrating into tissue. b Superparamagnetic particles aggregate due to dipole–dipole interaction in the presence of a magnetic field (i). The aggregate migrates towards the wall due to the radiation force in an acoustic field (ii). A rolling-type motion along the boundary is achieved by combining both fields. The assembled entities disassociate when the magnetic field is turned off

We investigated the migration of particles towards the sidewall of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microchannel by introducing particles of different size and material properties. The PDMS material serves as a good acoustic material for developing artificial vasculature model as the acoustic impedance of PDMS is of a similar order of magnitude to that of biomaterials that exist in a human body such as the blood, fat, brain and soft tissue56. Several acoustic phenomena, such as the acoustic radiation forces and the streaming-induced drag, contribute to particle motion, as shown in Fig. 2a. The acoustic radiation force, which is a time-averaged force that acts on particles in an inviscid fluid, comprises primary and secondary radiation forces. The primary radiation force arises due to the interactions of particles within the background pressure field, such as in the standing and travelling acoustic waves, and secondary radiation forces arise due to re-scattering of the waves at the neighbouring particles and the sidewalls of the channel. The primary radiation, F R, force acting on a single isolated particle in an acoustic pressure field can be estimated by the gradient of the Gor’kov potential. The time-averaged force acting on a particle of radius a, where a is much smaller than the acoustic wavelength, λ, in a one-dimensional standing wave of wavenumber k y and pressure field p = p acos(k y y)cos(ωt), can be expressed analytically as57:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where ϕ is the acoustophoretic contrast factor; ρ 0, ρ s denote the density of the liquid and particle, respectively; κ 0, κ s denote the compressibility of the water and particle, respectively, p a denotes the pressure amplitude, E a denotes the acoustic energy and y determines the position of the particle within the field. The acoustic contrast factor ϕ determines the directionality of the radiation force. The ϕ for polystyrene and superparamagnetic particles is positive and is calculated to be 0.22 and 0.43, respectively, which suggests that the particles will move to the pressure nodal lines, where pressure nodes may lie outside the microchannel, effectively driving the particles to its boundaries (Supplementary Notes 1 and 2).

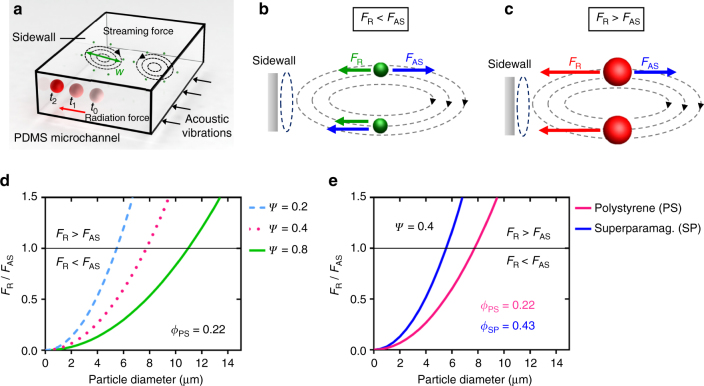

Fig. 2.

Analysis of particle trapping. a A schematic demonstrates the radiation force (F R) and the sidewall-induced streaming drag (F AS) that act on different sized particles. Large particles, which are illustrated in red, migrate to the channel sidewall by the radiation force. Small particles, which are shown in green, follow sidewall-induced streaming. b For a particle with a diameter a < a c, the acoustic streaming force dominates. c For a particle with a diameter a > a c, the acoustic radiation force dominates. d The plot shows the ratio of the acoustic radiation to streaming forces vs. different size polystyrene particle for various geometry factor, Ψ. Above the black line, F R > F AS, i.e. radiation force dominates and below the line, F R < F AS, i.e. streaming dominates. e The plot demonstrates the competing forces of the polystyrene (PS) and the superparamagnetic particles (SP) at Ψ ~0.4

We observed very little particle–particle interaction due to secondary acoustic radiation forces in the region away from the sidewalls, which suggests that the primary radiation force dominates particle migration. However, as particles approach the wall, they change direction and accelerate (Supplementary Fig. 3), which indicates a particle–wall interaction. Owing to the impedance mismatch between the water and the PDMS, the acoustic waves are partially reflected at their interface, which leads to secondary interactions between the walls of the channel and the particles58. The walls of the channel have been observed to attract the particles at close range. The particle–wall interaction contributes to the migration of particles to the wall, but this interaction is considered to be weak because the impedance mismatch between water and the PDMS is not significant (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Acoustic streaming is a steady bulk flow of fluid that arises due to viscous attenuation of the acoustic waves in the bulk of the fluid and the boundary layers, and it often contributes to the particle motion in an acoustic setup in microfluidics. The streaming flow rises from the channel sidewalls to the centre and is perpendicular to the direction of the long axis of the channel, as shown in Fig. 2a. The magnitude of the streaming velocity v AS scales as , where Ψ is a geometry-dependent factor of the microchannel and c 0 is the speed of sound in the liquid. Since the Reynolds number is low (R e < 0.0002), the drag force F AS that is induced by streaming can be estimated as follows:

| 4 |

where η is the dynamic viscosity of the liquid. Typically, the amplitude of the Stokes drag acting on spherical particles is on the order of the particle radius, and the acoustic radiation force scales with the particle volume. Thus, for smaller particles, the sidewall-induced streaming drag dominates particle motion until a transition size is reached, beyond which the radiation force becomes more dominant. The trapping mechanism can be understood by considering the ratio of the acoustic radiation forces in a standing wave field and the streaming-induced drag forces that can be expressed by the following relationship:

| 5 |

The relation is independent of the pressure amplitude, but depends on the particle and fluid properties, channel geometry and the wavenumber. When (F R)/(F AS) < 1, the streaming force dominates, as shown in Fig. 2b. When (F R)/(F AS) > 1, the acoustic radiation force dominates, as indicated in Fig. 2c. Figure 2d describes the ratio of the competing forces of different size polystyrene particle for various geometry-dependent factor, Ψ. The geometry factor of a rectangular microchannel is usually on the order of unity and matches our experimental condition when Ψ becomes 0.4, i.e. for a standing wave parallel to a wall57. The critical particle diameter, a c, which determines the transition, can be measured when the acoustic radiation force is exactly balanced by the streaming-induced drag force. The diameter a c of polystyrene particles is measured to be ~8 µm, which is determined by the intersection of the magenta plot at (F R)/(F AS) = 1 in Fig. 2d. Figure 2e compares the competing forces of the polystyrene and the superparamagnetic particles at Ψ ~0.4. As the acoustic contrast force of the superparamagnetic particles is higher than that of the polystyrene particles, the critical particle diameter becomes smaller. The superparamagnetic particle a c is estimated to be ~5.5 µm, which is determined by the intersection of the blue plot at (F R)/(F AS) = 1 in Fig. 2e.

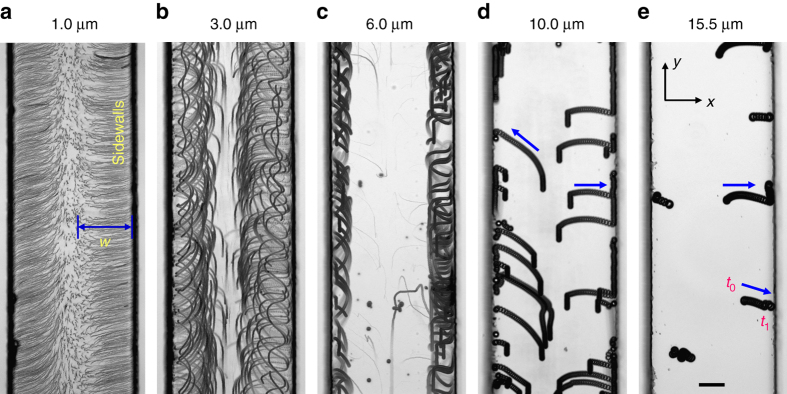

We verified the size dependence of the particle–wall interaction by introducing polystyrene particles of diameter 1, 3, 6, 10 and 15.5 µm, respectively. The 1, 3 and 6 µm particles follow the streamlines of the sidewall-induced streaming, as shown in Fig. 3a–c. The vortex width w, which is defined as the distance between the starting and ending vertex points of a vortex, decreases as the diameter of the particles increases as the radiation force becomes prominent. Conversely, the 10 and 15.5 µm particles migrate transversely towards the ±x direction and become trapped at the sidewalls, as shown in Fig. 3d and e (see also Supplementary Movie 1). Supplementary Figure 4 demonstrates the trapping of ~6 µm superparamagnetic particles, whereas, similar size polystyrene particles follow the flow streamlines. The experiment results closely agree with the analysis, as shown in Fig. 2d and e (see also Supplementary Movie 2).

Fig. 3.

Particle–wall interaction in an acoustic field. Image sequences demonstrate the particle–wall interaction of a 1, b 3, c 6, d 10 and e 15.5 μm diameter polystyrene particles, respectively, in a microfluidic channel. a–c Represents the sidewall-induced acoustic streaming developed within the microchannel. The vortex width w decreases with increasing particle diameter. d, e Demonstrates migration and trapping of 10 and 15.5 μm particles, respectively, at the channel sidewalls (see also Supplementary Movie 1). Blue arrows represent the particle trajectories, t 0 and t 1 represent the initial and final position, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm

Particle assembly and rolling motion

Inspired by the rolling motion of neutrophils on endovascular walls, we developed a propulsive mechanism based on a combined acoustic and magnetic actuation. The magnitude and the frequency of the magnetic field determine the assembly formation of the superparamagnetic particles. A magnetic field of a few milli-tesla ensures that the dipole–dipole interactions are large enough to attract neighbouring particles. At low rotational frequencies of the magnetic field the superparamagnetic particles tend to form chains. The dipole moments of the particles continuously realign themselves with the direction of the rotating magnetic field. As the Reynolds number is in the Stokes regime, the viscous torque due to drag instantly balances the magnetic torque. The viscous torque59 is defined as τ D ∝ ηl 3 ω, where η is the dynamic viscosity, l is the length of the chain and ω is the angular frequency of the chain. A longer chain formation of length l or a higher angular frequency ω increases the viscous torque. The interplay between magnetic and viscous forces determines the self-assembly configuration.

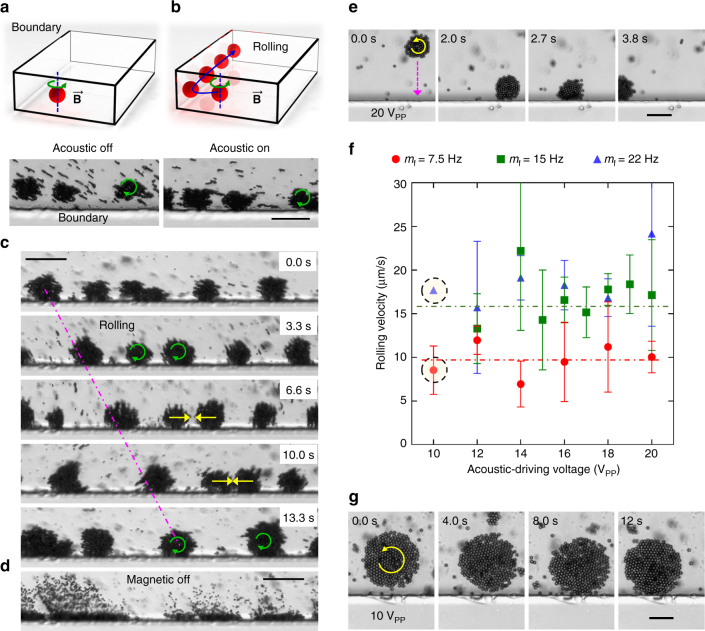

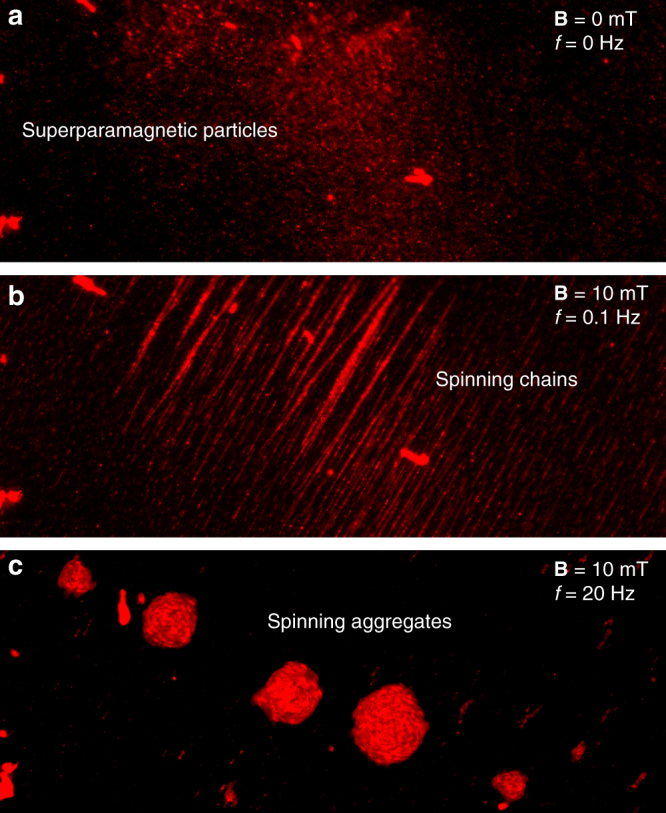

We sandwiched superparamagnetic particles between glass slides after which a low-strength rotating magnetic field is applied that results in a linear chain formation, as shown in Fig. 4a and b. As the rotational frequency of the magnetic field increases to 20 Hz, the spinning chains begins to fragment into satellites, and eventually the chain transforms into spinning orbits of diameter larger than ~6 µm, which is the critical particle diameter for acoustic trapping at the wall under the current setup, as shown in Fig. 4c (see also Supplementary Movie 3). At low Reynolds number, the time-reversal nature of the spinning orbits ensures negligible net motion. To generate noticeable motion, a swimmer needs to break either the symmetry of its motion or the symmetry of its surrounding geometry.

Fig. 4.

Particle interaction in a rotating magnetic field. a 1–2 µm fluorescent superparamagnetic particles are dispersed within the glass slides in the absence of a magnetic field. b The superparamagnetic particles self-assemble and form spinning chains at a rotational frequency of 0.1 Hz. c The spinning chains fragment into satellites, and eventually the chain transforms into spinning orbits at a higher frequency. The rotation of the spinning aggregates is demonstrated at a rotational frequency of 20 Hz, see also Supplementary Movie 3. Scale bar, 100 µm

After superparamagnetic particles are injected into the microfluidic channel, multiple spinning aggregates or orbits are formed by tuning the frequency of the magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 5a. The aggregates are shown to rotate in the clockwise direction. When the acoustic field is turned on at an appropriate frequency and amplitude, assembled particles, with a diameter larger than the critical diameter a c migrate to the boundaries due to the acoustic radiation force, as shown in Fig. 5b. As a result, the symmetry of the spinning aggregates is broken due to the presence of a boundary, and a subsequent rolling motion from left to right is achieved, as seen in Fig. 5c (see also Supplementary Movie 4). The assembled particles disassociate when the magnetic field is turned off (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Movie 5). As the acoustic field is still on, and the diameter of the particles is less than the critical diameter a c, the particles undergo sidewall streaming as shown in Fig. 5d. Figure 5e shows the counter-clockwise rotation of the aggregates and executing rolling from right to left when reached the wall (see also Supplementary Movie 6). We characterised the rolling behaviour and estimated the minimum power or voltage required by the piezo transducer to establish rolling. Figure 5f demonstrates the rolling velocity for different acoustic voltages at various magnetic rotational frequencies. As we decrease the acoustic voltage, rolling is achieved voltage until a lower acoustic voltage threshold is reached. For example, when the voltage is reduced to 12 or 10 VPP, a rolling motion is no longer obtained. At this critical voltage, most of the rollers are unaffected by the acoustic power and the few that reached the wall induced rolling at the wall transiently. As the contact between a roller and the wall remains weak, the roller also drifts away, as shown in Fig. 5g (see also Supplementary Movie 7). The experiments also suggest that the rolling speed is primarily dependent on the magnetic rotational frequencies, i.e. the average rolling speed increase from ~10 to 17 μm/s as the magnetic rotational frequency is doubled from 7.5 to 15 Hz.

Fig. 5.

Rolling motion in acoustic and magnetic fields. a The 1–2 µm superparamagnetic particles self-assemble and form spinning aggregates rotating in the clockwise direction in the presence of a magnetic field. b The aggregate migrates towards the channel wall due to the radiation force of an acoustic field. c Image sequence demonstrates the rolling-type propulsion along the sidewall of the microfluidic channel (Supplementary Movie 4). d The superparamagnetic particles disassociate as soon as the magnetic field is turned off. Scale bar of b–d is 50 µm. e Image sequence demonstrates the counter-clockwise motion of an aggregate and executing rolling when reached the wall under a magnetic field strength and rotation frequency of 20 mT and 20 Hz, respectively, at an acoustic driving voltage of 20 VPP (Supplementary Movie 6). Scale bar, 25 µm. f The plot of the rolling velocity against acoustic driving voltage at magnetic rotational frequencies (m f) of 7.5, 15 and 22 Hz, respectively, at 15 mT, of 2.9 µm superparamagnetic particles. Each data point represents the average rolling velocity analysed from 3–5 swimmers except data points at 10 VPP. The error bar represents the standard deviation (s.d.). g An aggregate is shown weak to no rolling at low-acoustic driving voltages of 10 VPP under a magnetic field strength and rotation frequency of 15 mT and 7.5 Hz, respectively (Supplementary Movie 7). Scale bar, 25 µm

The acoustic-based reaction force that is responsible for propulsion is perpendicular to the gravitational force and points in directions toward the sidewalls. For (F R)/(F AS) > 1, the acoustic radiation force dominates, which is balanced by the Stokes drag. The magnitude of the gravitation force incorporating buoyancy, can be calculated as , where g = 9.81 m/s2 is the gravitational constant, is in the range of piconewtons. The velocities of different sized particles reaching the sidewalls of the channel ranges from 5 to 10 μm/s. Although, both the acoustic radiation and the gravitation forces scale with the particle volume, the radiation force of a 10 µm polystyrene particles is approximately two orders of magnitude larger than its gravitational counterparts.

We believe that the rolling mechanism can potentially be used for in vivo applications. The developed method is not expected to lead to thrombosis as the local shear rate developed by rolling close to the wall is unlikely to prompt any shear-induced platelet activation. The shear rate, which is estimated as , where v ~20 μm/s is the rolling speed, and h ~30 μm is the diameter, is of at least few orders lower than the shear-induced platelet activation60.

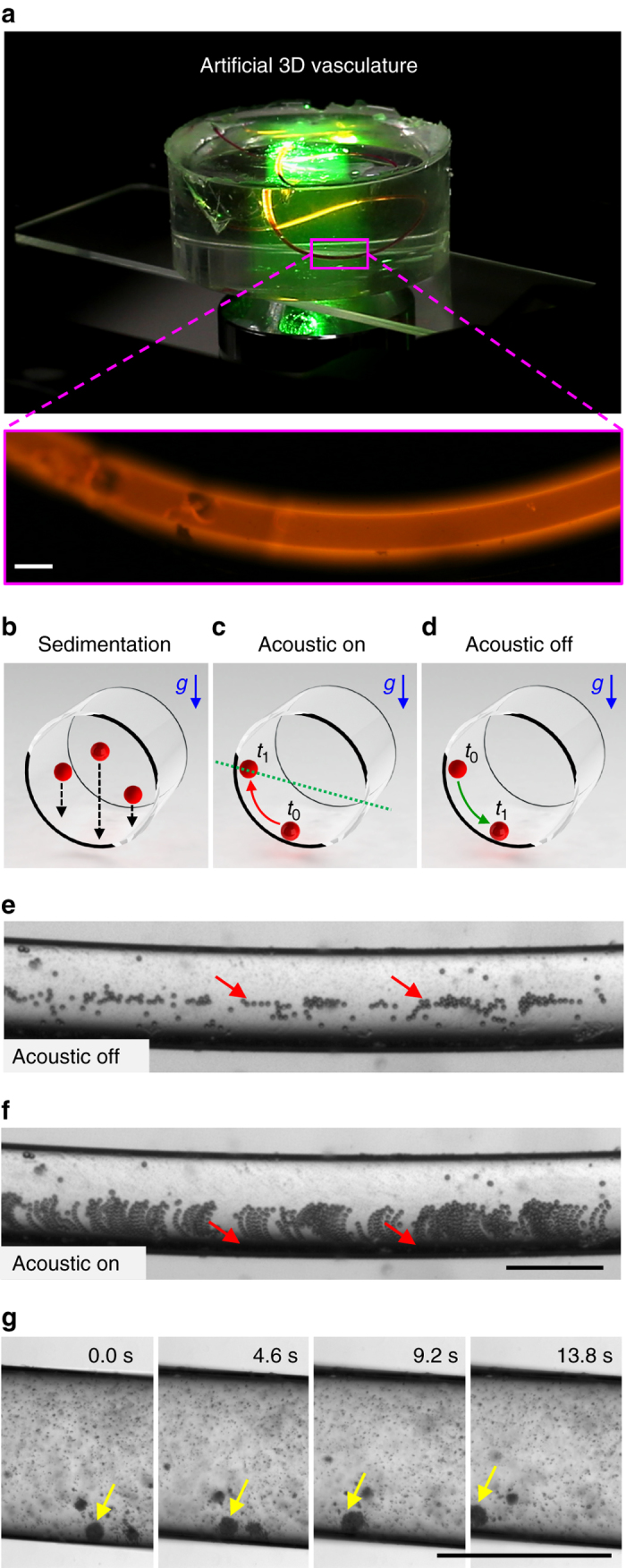

Particle motion in 3D channel

Developing propulsion with a geometric configuration that closely matches physiological settings is essential. Circular cross-sectional artificial vasculature are fabricated using a mould replica technique, as shown in Fig. 6a (see also ‘Methods’ section). The inset represents a channel filled with a fluorescently labelled dye. The channels have relatively large radii of curvature; as a result, imaging under microscopes with a high magnification objective becomes difficult. We used a low magnification objective lens (×2) and large particles (~1 µm in diameter) to compensate for the depth-of-field. To elucidate the acoustic trapping mechanism within the circular channel, particles are allowed to sediment at the bottom. The particles move vertically downward due to gravity and come in contact with the nearest surface (Fig. 6b). They gradually roll down along the curved surface and align themselves at the bottom of the channel. The sedimentation process is not required as particles interact with the boundary in an acoustic field. However, imaging and characterisation of particle migration become difficult as particles are trapped at different depths along the circular vessel.

Fig. 6.

Propulsion in a circular cross-sectional artificial vasculature. a The image represents a three-dimensional PDMS-based artificial vasculature with a circular cross section. The inset shows the fluorescently labelled channel. b The particles sediment vertically downward towards the nearest surface and then slowly roll down to the bottom of the channel due to gravity. c Particles roll up along the circular channel from state t 0 to t 1 in the presence of acoustic waves. The green dashed line in c represents the maximum height particles can reach. d Particle rolls down along the surface, from state t 0 to t 1 in the absence of acoustic waves. e The micrograph shows that particles aligned at the bottom of the channel in the absence of the acoustic waves. f Image sequence demonstrates the particles migration is moving upwards along the channel in the presence of the acoustic field, see also Supplementary Movie 8. g Rolling motion is executed in a circular channel, see also Supplementary Movie 9. All scale bars, 500 µm

When the acoustic field is activated, particles roll up along the circumference against the gravitational and contact forces from configuration t 0 to t 1, as shown in Fig. 6c. Once the acoustic field is turned off, the particles slowly roll down along the surface and realign themselves at the bottom, as shown in Fig. 6d. Figure 6e demonstrates sedimentation and alignment in the absence of an acoustic field. As soon as the acoustic field is turned on, the particles roll up along the surface. Figure 6f shows the image sequence of particle trajectories along the curved channel (see also Supplementary Movie 8). To verify our rolling-based propulsion along an artificial vasculature, superparamagnetic particles are injected into the channel. A rotating magnetic field is used to assemble particles above the critical diameter a c. When an acoustic field is applied, particles migrate to the channel wall, and a subsequent rolling motion results along the vessel, as shown in Fig. 6g (see also Supplementary Movie 9).

Discussion

We demonstrated a mechanism that self-assembles single particles and then transports them along boundaries of the microchannels by a combined acoustic and magnetic actuation technique. Our mechanism provides a potential design strategy to deliver drugs in hard-to-reach capillaries and can become advantageous in delivering nanodrugs to a tumour or leaky vasculature. Nanodrugs rarely reaches the tumour site due to factors arising from the interstitial fluid pressure, the slow diffusion rate of particles in the tissue, impaired blood supply, etc61, 62. We look forward to functionalizing nanodrugs with the iron-oxide particles to allow mapping of the vasculature and a simultaneous transportation.

The self-assembly of our swimmers also has numerous advantages over already synthesised or fabricated microswimmers, which have limited biocompatibility, i.e. they require additional surface modifications, which can be challenging for in vivo applications. In contrast, we can use biocompatible magnetic particles already approved for use as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. In addition, synthesised swimmers are associated with sophisticated and expensive fabrication procedures, whereas our concept involves a simple method of operation using commercially available superparamagnetic particles.

Currently, we have demonstrated rolling motion under no flow, and we assume that being close to the boundary may become favourable for the motion against the flow. The assembled superparamagnetic particles close to a wall experience many forces and torques that could become beneficial for particle margination and transport along or against the flow. As a proof-of-concept, we demonstrated assembly of superparamagnetic particles under a flow in a magnetic field (see also Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Movie 10). Future work will include a thorough investigation of rolling behaviour at different flow conditions.

Methods

Experimental setup

Our experimental design includes PDMS-based rectangular and circular cross-sectional microchannels and piezoelectric transducers (see also Supplementary Fig. 1). The transducer component is mounted on a glass slide adjacent to the channel using a thin layer of two-component epoxy glue, and is connected to an electronic function generator. The setup is mounted on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX 81) and imaged through a sensitive CMOS camera. The excitation frequency of the acoustic waves is modulated from 20 to 200 kHz, at 10 to 30 VPP. A custom built electromagnetic system (MagnebotiX MFG-100-i) with eight independently controlled coils was integrated with the microscope to generate the magnetic fields in the system, see also Supplementary Fig. 2. A maximum field strength and rotation frequency of 20 mT and 22.5 Hz, respectively, were used in our experiments. Commercially available superparamagnetic particles of diameter 1–2 µm (Polysciences) and 2.9 µm (COMPEL, Bangs Laboratories) are used in the experiments. A combination of acoustic and magnetic fields was utilised to demonstrate rolling motions near boundaries or walls.

Microfluidic channel

A straight single-layer PDMS microchannel was fabricated using a conventional soft lithography and mould replica technique. A silicon master mould for the microchannel was patterned using a positive photoresist (Shipley 1827, MicroChem, USA) and etched. The mould was then vapour coated with 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane (Sigma Aldrich, USA) such that the master mould does not disintegrate and to avoid any subsequent damage to the PDMS channel during the demoulding process. Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Base and Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Curing Agent (Dow Corning, USA) were mixed at a 10:1 (weight:weight) ratio and cast onto the silicon mould. The uncured PDMS on the silicon mould was then degassed in a vacuum desiccator for 2 h to remove any air microbubbles and later cured at 65 °C for 2 h. After gently removing the cured PDMS from the silicon mould, the inlets and the outlets were punched into the PDMS using a reusable biopsy punch (Harris Uni-Core, Ted Pella, USA). Then, the PDMS device was bonded to the cover glass after plasma treatment.

3D PDMS-based circular channel

3D channels are made by moulding electric wires into PDMS, which are removed after curing. Electrical wires of diameter 500 μm are embedded in a six-well plate (Corning). Then a 10:1 PDMS mixture is poured into the wells. To remove gas bubbles, they are refrigerated at −4 °C. The wells are kept at room temperature for half an hour and then placed on a hot plate at 60 °C for an hour. The wires are then carefully pulled out from the cured PDMS gels.

Data availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work has been financed by the European Research Council Grant ‘Soft Micro Robotics (SOMBOT),’ by the ERC Grant Agreement No. 743217. We would like to thank Janis Edelmann, Ayoung Hong, Samuel Charreyron and David Sargent for their helpful discussion.

Author contributions

D.A. initiated and designed the project. D.A., T.B. and N.B. contributed to the experimental design and scientific presentation. D.A., N.B., T.B. and N.L. performed all the experiments and data analysis. T.B., D.A. and J.D. developed the numerical and theoretical studies. D.A., T.B., J.D. and B.J.N. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the scientific discussion. D.A. and B.J.N. provided the overall guidance.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00845-5.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Daniel Ahmed, Email: dahmed@ethz.ch.

Bradley J. Nelson, Email: bnelson@ethz.ch

References

- 1.Purcell EM. Life at low Reynolds number. Am. J. Phys. 1977;45:3–11. doi: 10.1119/1.10903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg HC. Bacterial behaviour. Nature. 1975;254:389–392. doi: 10.1038/254389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray J, Hancock GJ. The propulsion of sea-urchin spermatozoa. J. Exp. Biol. 1955;32:802–814. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nosrati R, Driouchi A, Yip CM, Sinton D. Two-dimensional slither swimming of sperm within a micrometre of a surface. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8703. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drescher K, et al. Dancing volvox: hydrodynamic bound states of swimming algae. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.168101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams BJ, Anand SV, Rajagopalan J, Saif MTA. A self-propelled biohybrid swimmer at low Reynolds number. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3081. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez S, Soler L, Katuri J. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2015. Chemically powered micro- and nanomotors; pp. 1414–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soler L, Magdanz V, Fomin VM, Sanchez S, Schmidt OG. Self-propelled micromotors for cleaning polluted water. ACS Nano. 2013;7:9611–9620. doi: 10.1021/nn405075d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soler L, Sanchez S. Catalytic nanomotors for environmental monitoring and water remediation. Nanoscale. 2014;6:7175–7182. doi: 10.1039/C4NR01321B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srivastava SK, Guix M, Schmidt OG. Wastewater mediated activation of micromotors for efficient water cleaning. Nano Lett. 2015;16:817–821. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b05032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teo WZ, Pumera M. Motion control of micro-/nanomotors. Chem. A Eur. J. 2016;22:14796–14804. doi: 10.1002/chem.201602241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Pumera M. Fabrication of micro/nanoscale motors. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:8704–8735. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pumera M. Electrochemically powered self-propelled electrophoretic nanosubmarines. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1643–1649. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kherzi B, Pumera M. Self-propelled autonomous nanomotors meet microfluidics. Nanoscale. 2016;8:17415–17421. doi: 10.1039/C6NR06665H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang ST, Paunov VN, Petsev DN, Velev OD. Remotely powered self-propelling particles and micropumps based on miniature diodes. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nmat1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loget G, Kuhn A. Electric field-induced chemical locomotion of conducting objects. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palagi S, et al. Structured light enables biomimetic swimming and versatile locomotion of photoresponsive soft microrobots. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nmat4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu M, Zentgraf T, Liu Y, Bartal G, Zhang X. Light-driven nanoscale plasmonic motors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:570–573. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai B, et al. Programmable artificial phototactic microswimmer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016;11:1087–1092. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tasci TO, Herson PS, Neeves KB, Marr DWM. Surface-enabled propulsion and control of colloidal microwheels. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10225. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang B, et al. Undulatory locomotion of magnetic multilink nanoswimmers. Nano Lett. 2015;15:4829–4833. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b01981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H-W, Sakar MS, Petruska AJ, Pane S, Nelson BJ. Soft micromachines with programmable motility and morphology. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12263. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson BJ, Kaliakatsos IK, Abbott JJ. Microrobots for minimally invasive medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2010;12:55–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-010510-103409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klotsa D, Baldwin KA, Hill RJA, Bowley RM, Swift MR. Propulsion of a two-sphere swimmer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;115:1–5. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.248102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed D, et al. Artificial swimmers propelled by acoustically activated flagella. Nano Lett. 2017;16:4968–4974. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dijkink RJ, Dennen JPVan, Der, Ohl CD. & Prosperetti, a. The ‘acoustic scallop’: a bubble-powered actuator. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2006;16:1653–1659. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/16/8/029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed D, et al. Selectively manipulable acoustic-powered microswimmers. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9744. doi: 10.1038/srep09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Castro LA, Hoyos M, Mallouk TE. Autonomous motion of metallic microrods propelled by ultrasound. ACS Nano. 2012;6:6122–6132. doi: 10.1021/nn301312z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertin N, et al. Propulsion of bubble-based acoustic microswimmers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2015;4:64012. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.4.064012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, et al. Magneto-acoustic hybrid nanomotor. Nano Lett. 2015;15:4814–4821. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b01945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed D, Dillinger C, Hong A, Nelson BJ. Artificial acousto-magnetic soft microswimmers. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2017;2:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed D, Mao X, Shi J, Juluri BK, Huang TJ. A millisecond micromixer via single-bubble-based acoustic streaming. Lab. Chip. 2009;9:2738–2741. doi: 10.1039/b903687c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed D, Mao X, Juluri BK, Huang TJ. A fast microfluidic mixer based on acoustically driven sidewall-trapped microbubbles. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2009;7:727–731. doi: 10.1007/s10404-009-0444-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozcelik A, et al. An acousto fluidic micromixer via bubble inception and cavitation from microchannel sidewalls. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:5083–5088. doi: 10.1021/ac5007798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed D, et al. Acousto fluidic chemical waveform generator and switch. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:11803–11810. doi: 10.1021/ac5033676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed D, et al. Tunable, pulsatile chemical gradient generation via acoustically driven oscillating bubbles. Lab. Chip. 2013;13:328–331. doi: 10.1039/C2LC40923B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi J, et al. Acoustic tweezers: patterning cells and microparticles using standing surface acoustic waves (SSAW) Lab. Chip. 2009;9:2890–2895. doi: 10.1039/b910595f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins DJ, et al. Two-dimensional single-cell patterning with one cell per well driven by surface acoustic waves. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8686. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Y, et al. Acoustofluidic relay: sequential trapping and transporting of microparticles via acoustically excited oscillating bubbles. J. Lab. Autom. 2014;19:137–143. doi: 10.1177/2211068213485748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarz T, Hahn P, Petit-Pierre G, Dual J. Rotation of fibers and other non-spherical particles by the acoustic radiation torque. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2014;18:65–79. doi: 10.1007/s10404-014-1408-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzo A, et al. Holographic acoustic elements for manipulation of levitated objects. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8661. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmed D, et al. Rotational manipulation of single cells and organisms using acoustic waves. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11085. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Q, Sariola V, Latifi K, Liimatainen V. Controlling the motion of multiple objects on a Chladni plate. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12764. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiklund M. Acoustofluidics 12: biocompatibility and cell viability in microfluidic acoustic resonators. Lab. Chip. 2012;12:2018–2028. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40201g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanherberghen B, et al. Ultrasound-controlled cell aggregation in a multi-well chip. Lab. Chip. 2010;10:2727–2732. doi: 10.1039/c004707d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding X, et al. Cell separation using tilted-angle standing surface acoustic waves. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:12992–12997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413325111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen K, et al. Rapid formation of size-controllable multicellular spheroids via 3D acoustic tweezers. Lab. Chip. 2016;22:133–186. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00444j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Errico C, et al. Ultrafast ultrasound localization microscopy for deep super-resolution vascular imaging. Nature. 2015;527:499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature16066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen-Jeffries K, Browning RJ, Tang MX, Dunsby C, Eckersley RJ. In vivo acoustic super-resolution and super-resolved velocity mapping using microbubbles. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2015;34:433–440. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2359650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carpentier A, et al. Clinical trial of blood-brain barrier disruption by pulsed ultrasound. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:343re2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoellhammer CM, et al. Ultrasound-mediated gastrointestinal drug delivery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:310ra168. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bremond N, Arora M, Ohl CD, Lohse D. Controlled multibubble surface cavitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:224501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.224501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zwaan E, Le Gac S, Tsuji K, Ohl CD. Controlled cavitation in microfluidic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:254501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.254501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng J, Yuan J, Cho SK. Micropropulsion by an acoustic bubble for navigating microfluidic spaces. Lab. Chip. 2015;15:1554–1562. doi: 10.1039/C4LC01266F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H, Kreider W, Brayman AA, Bailey MR, Matula TJ. Blood vessel deformations on microsecond time scales by ultrasonic cavitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;106:034301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.034301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azhari, H. Basics of Biomedical Ultrasound For Engineers (Wiley, 2010).

- 57.Bruus H. Acoustofluidics 10: scaling laws in acoustophoresis. Lab. Chip. 2012;12:1578. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21261g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baasch T, Leibacher I. Multibody dynamics in acoustophoresis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017;141:1664. doi: 10.1121/1.4977030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keshoju K, Xing H, Sun L. Magnetic field driven nanowire rotation in suspension. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;91:12–15. doi: 10.1063/1.2789184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holme PA, et al. Shear-induced platelet activation and platelet microparticle formation at blood flow conditions as in arteries with a severe stenosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:646–653. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.17.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011;7:653–664. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nichols JW, Bae YH. Odyssey of a cancer nanoparticle: from injection site to site of action. Nano Today. 2012;7:606–618. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.