Abstract

Chocolate is a product processed from cocoa rich in flavonoids, antioxidant compounds, and bioactive ingredients that have been associated with both its healthy and sensory properties. Chocolate production consists of a multistep process which, starting from cocoa beans, involves fermentation, drying, roasting, nib grinding and refining, conching, and tempering. During cocoa processing, the naturally occurring antioxidants (flavonoids) are lost, while others, such as Maillard reaction products, are formed. The final content of antioxidant compounds and the antioxidant activity of chocolate is a function of several variables, some related to the raw material and others related to processing and formulation. The aim of this mini-review is to revise the literature on the impact of full processing on the in vitro antioxidant activity of chocolate, providing a critical analysis of the implications of processing on the evaluation of the antioxidant effect of chocolate in in vivo studies in humans.

Keywords: cocoa, chocolate, processing, polyphenols, antioxidant activity, chronic intervention studies

Introduction

Chocolate, thanks to its unique structure and flavor, is a food usually consumed for pleasure that has been recently reconsidered as a source of healthy compounds. Chocolate is rich in polyphenols such as flavanols, which possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and have a protective effect against degenerative diseases (1–6). Procyanidin and flavanol polymers also contribute to chocolate taste by affecting bitterness and astringency (7, 8). The polyphenol content of chocolate depends on many factors, some related to the raw material, and others related to processing (9, 10).

The majority of published reviews aim at analyzing the impact of processing on the polyphenol content of cocoa more than on its functional properties, focusing only on selected processing steps deemed to have a major impact on phenolic content, and, sometimes, without a specific discussion of all the single steps (9–11).

This mini-review aims at revising the literature on the impact of full processing on the in vitro antioxidant properties of chocolate providing a critical analysis of the implication of processing on the antioxidant effect of chocolate in in vivo studies in humans.

Chocolate Processing in Brief

Chocolate-making consists of a multistep process. At harvest, cocoa fruit contains about 30–40 seeds covered by a mucilaginous pulp removed by yeast and bacteria during fermentation, which is a key step for the development of the chocolate flavor, since it produces aroma precursors. After fermentation, a drying step is required to reduce the water content to 5–7%; this ensures product stability before further processing. Dried cocoa beans or nibs (i.e., beans without the outer shell) are then roasted to further develop the chocolate flavor. The next step in cocoa processing involves nib grinding to convert the solid nibs into a liquid paste (liquor).

For the production of dark chocolate, the basic ingredients are cocoa liquor, sugar, cocoa butter, and emulsifiers. Milk and other ingredients may be added, mixed and then refined to reduce the particle sizes of solids. After refining, the conching operation, which consists of the agitation of the chocolate mass at high temperatures, and finally tempering, which consists in a heating, cooling and mixing process, are required for the development of the final texture and flavor.

Phenolic Antioxidants in Chocolate

Polyphenols are the main class of antioxidants in unfermented cocoa beans, and they account for approximately 2% w/w (12). Cocoa contains several classes of phenolic compounds among which, flavanols (37%), proanthocyanidins (58%), and anthocyanins (4%) (11).

Flavanols, and, in particular, flavan-3-ols, are the most studied compounds in cocoa. The main flavan-3-ols, are (−)-epicatechin and (+)-catechin, which have an antioxidant activity of 2.4–2.9 trolox equivalents (TE) using the 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay and 2.2 TE using the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, but they can be epimerized into (+)-epicatechin and (−)-catechin during processing into chocolate (5, 13).

Flavan-3-ols may group together to form dimeric, oligomeric, or polymeric combinations of units that are denominated proanthocyanidins, among which we can include procyanidins (oligomers of epicatechin). Oligomeric and polymeric proanthocyanidins are present in raw beans but could further polymerize during processing (14–16). The procyanidin dimers (B1, B2, B3, and B5) and trimer C1, as well as oligomers, up to decamers, have been reported in cocoa and chocolate (12, 17–19). The average antioxidant activity of procyanidin dimers is about 6.5, and that of trimers is 7–8 TE using the ABTS assay. Monomers, dimers, and trimers account for almost 33% of the antioxidant activity of cocoa. The antioxidant activity of procyanidin polymers seems to increase depending on the degree of polymerization even though polymerization decreases the concentration of polyphenols; the relative contribution of decamers to the total antioxidant activity is low (14).

Esters of catechins, such as gallocatechins and epigallocatechins, can be found in raw beans (20) but could also be formed during processing, in particular, during roasting (16), whereas esters of epigallocatechins, such as epigallocatechingallate, have only been reported in chocolate (21).

Anthocyanins that have been reported in fresh beans (22) are degraded during fermentation due to hydrolysis and further polymerization in condensed tannins (20).

Minor phenolic compounds are also present (i.e., flavonols, phenolic acids, simple phenols and isocoumarins, stilbenes, and their glucosides), but their content is low and their contribution to total antioxidant activity is limited.

Apart from polyphenols, chocolate contains other process-derived antioxidants such as Maillard reaction products (MRPs) that form during high temperature processing, among which drying, roasting, and conching.

Effect of Cocoa Processing on Antioxidant Activity

The evaluation of the antioxidant (i.e., phenolics) content and activity much depends on the extraction solvent and procedure (9), which is not standardized throughout literature on cocoa, so data are difficult to compare. In the colorimetric assays of the total phenolic content (TPC), discrepancies may arise due to the phenolic compounds used as reference for the standard curve as well as to the presence of reducing compounds, interfering with the assay. Regarding antioxidant activity, comparison of results could be problematic due to the large number of heterogeneous tests used. The most common assays [ABTS, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), oxygen radical antioxidant capacity, total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter (TRAP), and FRAP] are based on different reaction mechanisms (single electron transfer, hydrogen atom transfer, or mixed mechanisms) and could give discordant results depending on the most abundant antioxidant molecules in the system and their interactions.

Cocoa Beans

Cocoa beans are the seeds of the tropical Theobroma cacao L. tree. There are four types of cocoa: Forastero, which comprises 95% of the world production of cocoa and is the most widely used; Criollo, which is rarely grown because of disease susceptibility; Trinitario, which is a more disease-resistant hybrid of Criollo and Forastero; and Nacional, which is grown only in Ecuador (20, 23). The concentration of phenolic compounds in cocoa beans is highly variable and depends primarily on genetics, and then on many other factors such as geographical regions of cultivation, agronomical practices and climatic conditions (20).

Generally, Criollo cocoa beans have a lower phenolic content compared to the Forastero variety (10). Unfortunately, few studies on the phenolic content and antioxidant properties of unfermented beans are available and most results refer to beans that have undergone fermentation, drying or both these processes. When unfermented beans are considered, the total phenolic content results in a range between 67 and 149 mg/g (24) or 120 and 180 mg/g (25). Large differences in the content of total polyphenols and individual phenolic compounds in unfermented ripe seeds of Forastero, Trinitario, and Criollo cocoa of six different origins were reported (22). Antioxidant activities of 709 ± 17 µM and 240–490 mmol TE/g were reported when the DPPH test was used (26, 27); however, the tests differed as regards the experimental conditions adopted. Values of 1.29–2.29 mmol TE/g and 600–800 mmol TE/gdw were found with the ABTS method (14, 27) while reducing activities in the range 713–930 mmol Fe2+/gdw were obtained when using the FRAP method (14).

Fermentation

Fermentation of the pulp surrounding the beans represents the first important step for the development of chocolate flavor and taste since it produces aroma precursors. During fermentation, which can last from 5 to 10 days, the combination of endogenous and microbial enzymatic activities, along with the rise of temperature to about 50°C, and the diffusion of metabolites into and out of the cotyledons, allow polyphenols to polymerize and react with other compounds to form complexes. Fermentation is thus considered responsible for the decrease of the flavan-3-ol content, (−)-epicatechin in particular.

The level of polyphenol reduction is proportionate to the degree of fermentation (25, 28–30). Significant differences can be detected in the TPC content after fermentation as determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent: a range between 120–140 mg/g was found by Di Mattia et al. (14); a similar range (90–120 mg/g) was reported by Niemenak et al. (24) and Afoakwa (20). Higher levels (220 mg/g) were detected by Ryan et al. (31) while lower contents were determined by do Carmo Brito et al. (32). The antioxidant activity, as determined by the ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP methods, generally followed the same fate of the phenolic content, with reduction levels of 20–40% (14, 32). In the work by Suazo et al. (26), a reduction of about 80% was determined in the DPPH values while an increase in the total antioxidant capacity (+50–160%), evaluated using DPPH and ABTS methods, was observed in cocoa varieties after spontaneous fermentation (27).

Drying

The aim of cocoa drying is to remove water so as to reach moisture content below 7% and is usually carried out by sun heating in static conditions but heating dryers are also used.

Sun drying reduces the polyphenol content to different extents: Camu et al. (29) reported a reduction from 77 to 44%, Di Mattia et al. (14), a 72% reduction, Hii et al. (11), a 30% reduction, and finally, de Brito et al. (28), a 26% reduction. The reduction of polyphenols depends on climatic conditions (29), and reduction levels ranging from 77 to 44% were reported for the same cocoa sample dried in different seasons.

Sun drying not only affects the polyphenol content but also the antioxidant activity of cocoa beans, and a reduction of about 70% of TPC and 80% in flavan-3-ols was shown to determine a decrease of 70 ± 5% in antioxidant activity depending on the method used (14).

Experimental data on air drying are scarce; an industrial process carried out on a batch of 1,600 kg of cocoa beans for 11 days at a temperature of 60°C, decreased the content of TPC (52%) and flavan-3-ols (66%) inducing a 60 ± 5% decrease of antioxidant activity, depending on the assay (14). Hot air drying of cocoa beans has also been studied in laboratory scale conditions (11, 33–36), and the mean reduction of total polyphenols was about 45%, but this could dramatically change depending on process conditions.

Roasting

Roasting determines the formation of the characteristic color, aroma, taste, and texture of roasted cocoa beans (37). Roasting temperatures of 120–150°C and times of 5–120 min are used (37, 38), and under these conditions, a decrease of flavanols and TPC has been observed.

During roasting, monomeric flavanols are reduced from 0 to 95% depending on the cultivar and the roasting temperature (16, 18, 19). High roasting temperatures improve the rate of polyphenol degradation, but in some cases a lower degradation was observed at high temperatures due to reduced processing times (16). Roasting temperature being equal, polyphenol degradation could be reduced by about 20% by adopting “high” relative humidity (5%) roasting conditions (18).

Roasting generally depletes the antioxidant activity of cocoa. Arlorio et al. (39) reported a decrease between 37 and 48% after pre-roasting at 100°C and roasting different varieties of cocoa at 130°C. Hu et al. (40) reported a decrease of antioxidant activity between 44 and 50% during roasting at high temperature (190°C) for short times (15 min) regardless of the assay used to test it. Ioannone et al. (16) observed a decrease of antioxidant activity during the first part of the roasting process and an increase during roasting time due to the formation of MRPs (16, 41). They reported a FRAP decrease of 51 and 45% at 125 and 145°C, respectively, as well as a TRAP increase of 7% at 125°C and a TRAP decrease of 20% at 145°C at the end of roasting. Dramatic differences between FRAP and TRAP values could be explained by considering MRP formation during roasting (41) since MRPs show a high chain-breaking activity despite their low reducing potential (42). A low roasting temperature (125°C) led to higher TRAP values but lower FRAP values than a high roasting temperature (145°C).

Conching

Conching is a unit operation based on the agitation of chocolate mass at high temperatures (above 50°C); it is an essential step for the development of proper viscosity and the attainment of final texture and flavor (23, 43). Different time/temperature combinations are selected according to the final product to be manufactured. In dark chocolates, temperatures ranging from 70 to 90°C can be used; variations in conching time and temperature combinations modify chocolate texture and flavor (44–46). Little attention has been paid to conching and its effect on polyphenol content and antioxidant properties. However, the conching process does not impair the phenolic content and pattern, as well as antioxidant activity since small yet not significant variations (3%) were found, regardless of the time/temperature combination applied (47–49). The same results were reported by Di Mattia et al. (15) for the TPC; however, authors reported a significant increase of trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (+16% on average) after conching.

Complete Process

The content and antiradical activity of cocoa beans, nibs, cocoa mass, and finished dark chocolate obtained from fermented beans from different geographical origins have been studied (50). Generally a progressive decrease of the phenolic content was observed upon processing, with roasting playing a major role. Nonetheless, the most significant losses in both phenolic content and antioxidant activity emerged in the final steps of processing, and in particular between the conched and non-tempered chocolate and the dark chocolate. The authors remarked that the results were ascribable to a dilution and even to an antagonistic effect produced by the addition of other ingredients. However, it is not clear if the authors considered the recovery of phenolic compounds on the basis of the amount used in the recipe (40% of cocoa mass).

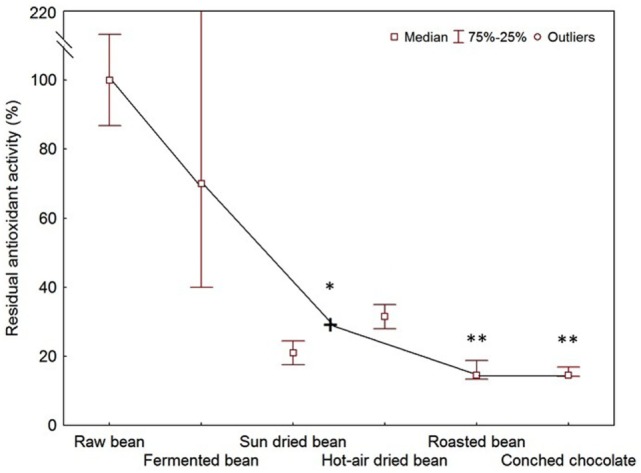

Despite few attempts, the concurrent evaluation of the changes of polyphenol content and antioxidant activity upon all the processing steps is actually lacking and further investigations are needed. A general trend of the variation of antioxidant activity during processing is shown in Figure 1, obtained by taking into account the losses reported in works where single manufacturing steps were considered.

Figure 1.

Residual antioxidant activity of cocoa processed products after each processing step. *Mean of sun drying and hot air drying data; **data calculated on the mean of sun drying and hot air drying data. The top of the error bar of the second point on the x-axis overlaps with the figure frame.

Antioxidant Effect of Chocolate In Vivo

As far as chronic intervention studies in humans are concerned, there are no published studies that consider the effect of processing on the antioxidant properties of chocolate. This is a big gap in literature that deeply impairs the massive amount of work performed on chocolate processing optimization.

Literature data from 10 human chronic intervention studies investigating the effect of chocolate intake on plasma and urinary levels of markers of antioxidant function, isoprostanes, and non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity (NEAC) were reviewed, and the results are presented on Table 1, where type of chocolate, number of intervention days, number of subjects, dose/day, effect on isoprostanes, effect on NEAC, and effect on polyphenols were described. Plasma/serum/urine isoprostanes, plasma NEAC, and polyphenols were assessed in nine, six, and seven studies, respectively.

Table 1.

Chronic intervention studies in humans providing cocoa-based products: effect on F2-IsoP, NEAC,a and PP.a

| Food | Days | Subjects | Dose/day | F2-IsoP | NEACa | PPa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid-rich dark chocolate | 14 | 11 | 46 g | ↔ Plasma | ↔ | ↑ EC | (2) |

| Cocoa tablets | 28 | 13 | 6 Tablets | ↔ Plasma | ↔ | ↑ EC, C | (51) |

| Dark chocolate and cocoa powder drink | 42 | 25 | 36.90 g of dark chocolate and 30.95 g of cocoa powder drink | ↔ Urine | ↔ | ↔ Total phenols | (52) |

| Dark chocolate | 21 | 15 | 75 g | ↔ Plasma | ↔ | (53) | |

| Polyphenols-rich dark chocolate | 21 | 15 | 75 g | ↔ Plasma | ↔ | (53) | |

| Polyphenols-rich dark chocolate | 126 | 22 with prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension | 6.3 g | ↔ Plasma | ↔ EC, C, procyanidin B2, procyanidin B2 gallate | (54) | |

| PP-rich milk chocolate | 14 | 28 | 105 g | ↔ | ↔ C, EC | (55) | |

| Flavonoid-rich dark chocolate | 14 | 20 | 45 g | ↔ Serum | (56) | ||

| Dark chocolate | 14 | 19 NASH 1 | 40 g | ↓ Serum | ↑ ECMet, TP | (57) | |

| Milk chocolate | 14 | 19 NASH 1 | 40 g | ↔ Serum | ECMet,b ↔ TP | (57) |

aPlasma and/or serum measurements.

↑, increase; ↔, no change; ↓, decrease; F2-IsoP, F2-isoprostanes; NEAC, non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity; PP, polyphenols; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; EC, epicatechin; C, catechin; ECMet, epicatechin-3O-methylether.

bDiscrepancy between table and text. Modified from Petrosino and Serafini (58).

On the basis of existing data, only one study showed an effect of chocolate on markers of antioxidant functions in humans. An increase in plasma polyphenol levels, namely, epicatechin, catechin, epicatechin-3O-methylether, and total phenolics, following a cocoa-based product supplementation period was detected in three studies out of seven. Increases were not correlated to any changes in markers of antioxidant function except for Loffredo et al. (57).

Although, from this analysis, it could be inferred that antioxidant networks do not respond very well to dietary supplementation with chocolate, some considerations are required. First of all, we need to consider the high heterogeneity of the reviewed studies, involving not only very different chocolate sources and doses of supplementation but also different size power, type of subjects, and duration of the supplementation; all variables that might affect the outcome of the trial.

It seems that all the different formulations that were used in the studies, such as tablets and chocolate drinks, failed to display any significant effect. Moreover, in agreement with previous evidences in vivo (1), milk chocolate does not produce any significant antioxidant effect in humans, and it has been utilized as control (57) in the only study where an effect was detected with dark chocolate.

The outcome of a study may also depend on the kind of subjects involved, namely, on their health condition. As previously stated, elevated levels of isoprostanes have been reported in individuals with diseases, or related risk factors, in which oxidative stress is involved; these subjects are supposed to have a higher requirement of antioxidants and, thus, to better respond to dietary intervention. In this respect, it is interesting to highlight that the only study where chocolate displayed an antioxidant effect in humans was conducted on subjects with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis diseases characterized by a non-physiological condition of oxidative stress. When oxidative stress is ongoing, endogenous antioxidants are not able to inhibit the production of free radicals efficiently; therefore, the contribution of exogenous antioxidants in diets may be crucial to support the endogenous redox system providing a clear effect on antioxidant status markers in humans (59–61). This aspect might explain the lack of effect observed for chocolate products, since all the studies, except the one where chocolate was effective, were conducted on healthy subjects characterized by a physiological equilibrium of free radicals and antioxidants. A systematic review (62) and a meta-analysis (63) support this hypothesis by showing that plant food, as well as chocolate supplementation, displays a better efficiency on antioxidant defense markers when the trials are conducted on subjects with oxidative stress-related risk factors rather than on healthy subjects. Moreover, in a large clinical trial on subjects characterized by cardiovascular disease risk factors, the PREDIMED study, it was shown that the efficiency of the supplementation of Mediterranean diet with antioxidant rich foods for 1 year was correlated with the baseline levels of antioxidant defenses (64). Subjects starting from lower levels of plasma NEAC showed a higher increase in NEAC compared to subjects starting from higher baseline levels of antioxidants, highlighting the importance of the redox “condition” of the subject on the efficiency of antioxidant supplementation.

Conclusion

Chocolate processing affects the content of total polyphenols as well as the antioxidant activity of chocolate and proper technology could “optimize” polyphenol retention and the in vitro antioxidant activity of chocolate. This work highlights the need to provide evidence of chocolate functionality in human beings to identify a proper technological process for chocolate processing. This is a necessary step to suggest to consumers the “optimal” doses of chocolate, which optimizes the functional effect by avoiding potential side effects, such as a high-energy load.

Human trials should be conducted mainly on subjects characterized by oxidative stress conditions, sharing a common requirement for dietary antioxidants, to increase the chance of observing an antioxidant effect in vivo.

Author Contributions

CM, GS, and DM contributed to draft the section related to food chemistry and technology; MS contributed to draft the section related to nutrition; and CM, GS, DM, and MS contributed to data analysis and interpretation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research project was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relations that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ABTS, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power; MRPs, Maillard reaction products; TE, trolox equivalents; TEAC, trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity; TPC, total phenolic content; ORAC, oxygen radical antioxidant capacity; TRAP, total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter; NEAC, non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

References

- 1.Serafini M, Bugianesi R, Maiani M, Valtuenˇa S, De Santis S, Crozier A. Plasma antioxidants from chocolate. Nature (2003) 424:1013. 10.1038/4241013a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engler MB, Engler MM, Chen CY, Malloy MJ, Browne A, Chiu EY, et al. Flavonoid-rich dark chocolate improves endothelial function and increases plasma epicatechin concentrations in healthy adults. J Am Coll Cardiol (2004) 23:197–204. 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heiss C, Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Perre` S, Schroeter H. Acute consumption of flavonoid-rich cocoa and the reversal of endothelial dysfunction in smokers. J Am Coll Cardiol (2005) 46:1276–83. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jourdain C, Tenca G, Deguercy A, Troplin P, Poelman D. In vitro effects of polyphenols from cocoa and [beta]-sitosterol on the growth of human prostate cancer and normal cells. Eur J Cancer Prev (2006) 15:353–61. 10.1097/00008469-200608000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper KA, Donovan JL, Waterhouse AL, Williamson G. Cocoa and health: a decade of research. Br J Nutr (2008) 99:1–11. 10.1017/S0007114507795296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corti R, Flammer AJ, Hollenberg NK, Luscher TF. Cocoa and cardiovascular health. Circulation (2009) 108:1433–41. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komes D, Belščak-Cvitanović A, Horžić D, Drmić H, Sˇkrabal S, Milicˇević B. Bioactive and sensory properties of herbal spirit enriched with cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) polyphenolics. Food Bioprocess Technol (2012) 5:2908–20. 10.1007/s11947-011-0630-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun-Waterhouse D, Wadhwa SS. Industry-relevant approaches for minimising the bitterness of bioactive compounds in functional foods: a review. Food Bioprocess Technol (2012) 6:607–27. 10.1007/s11947-012-0829-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollgast J, Anklam E. Review on polyphenols in Theobroma cacao: changes in composition during the manufacture of chocolate and methodology for identification and quantification. Food Res Int (2000) 33:423–47. 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00068-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oracz J, Zyzelewicz D, Nebesny E. The content of polyphenolic compounds in cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.), depending on variety, growing region and processing operations: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2015) 55:1176–92. 10.1080/10408398.2012.686934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hii CL, Law CL, Suzannah S, Misnawi J, Cloke M. Polyphenols in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.). As J Food Ag Ind (2009) 2:702–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter LJ, Ma Z, Chan BG. Cacao procyanidins: major flavanoids and identification of some minor metabolites. Phytochemistry (1991) 30:1657–63. 10.1016/0031-9422(91)84228-K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caligiani A, Cirlini M, Palla G, Ravaglia R, Arlorio M. GC-MS detection of chiral markers in cocoa beans of different quality and geographic origin. Chirality (2007) 19:329–34. 10.1002/chir.20380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Mattia CD, Martuscelli M, Sacchetti G, Scheirlinck I, Beheydt B, Mastrocola D, et al. Effect of fermentation and drying on procyanidins, antiradical activity and reducing properties of cocoa beans. Food Bioprocess Tech (2013) 6:3420–32. 10.1007/s11947-012-1028-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Mattia CD, Martuscelli M, Sacchetti G, Beheydt B, Mastrocola D, Pittia P. Effect of different conching processes on procyanidins content and antioxidant properties of chocolate. Food Res Int (2014) 63:367–72. 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ioannone F, Di Mattia CD, De Gregorio M, Sergi M, Serafini M, Sacchetti G. Flavanols, proanthocyanidins and antioxidant activity changes during cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) roasting as affected by temperature and time of processing. Food Chem (2015) 174:256–62. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper KA, Campos-Gimenez E, Jimenez-Alvarez D, Nagy K, Donovan JL, Williamson G. Rapid reversed phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography analysis of the major cocoa polyphenols and inter-relationships of their concentrations in chocolate. J Agric Food Chem (2007) 55:2841–7. 10.1021/jf063277c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Z∙yz∙elewicz D, Krysiak W, Oracz J, Sosnowska D, Budryn G, Nebesny E. The influence of the roasting process conditions on the polyphenol content in cocoa beans, nibs and chocolates. Food Res Int (2016) 89:918–29. 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.03.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kothe L, Zimmermann BF, Galensa R. Temperature influences epimerization and composition of flavanol monomers, dimers and trimers during cocoa bean roasting. Food Chem (2013) 141:3656–63. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afoakwa EO. Chocolate Science and Technology. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokusoglu O, Kemal Ünal M. Optimized method for simultaneous determination of catechin, gallic acid, and methylxanthine compounds in chocolate using RP-HPLC. Eur Food Res Technol (2002) 215:340–6. 10.1007/s00217-002-0565-3D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elwers S, Zambrano A, Rohsius C, Lieberei R. Differences between the content of phenolic compounds in Criollo, Forastero and Trinitario cocoa seed (Theobroma cacao L.). Eur Food Res Technol (2009) 229:937–48. 10.1007/s00217-009-1132-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckett ST. The Science of Chocolate. Cambridge: RSC Publishing; (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niemenak N, Rohsius C, Elwers S, Ndoumou DO, Lieberei R. Comparative study of different cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) clones in terms of their phenolics and anthocyanins contents. J Food Compos Anal (2006) 19:612–9. 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim H, Keeney PG. (−)-Epicatechin content in fermented and unfermented cocoa beans. J Food Sci (1984) 49:1090–2. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb10400.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suazo Y, Davidov-Pardo G, Arozarena I. Effect of fermentation and roasting on the phenolic concentration and antioxidant activity of cocoa from Nicaragua. J Food Qual (2014) 37:50–6. 10.1111/jfq.12070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batista NN, de Andrade DP, Ramos CL, Dias DR, Schwan FR. Antioxidant capacity of cocoa beans and chocolate assessed by FTIR. Food Res Int (2016) 90:313–9. 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Brito ES, Pezoa Garcia NH, Gallao MI, Corelazzo AL, Fevereiro PS, Braga MR. Structural and chemical changes in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) during fermentation, drying and roasting. J Sci Food Agric (2000) 81:281–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camu N, De Winter T, Addo SK, Takrama JS, Bernaert H, De Vuyst L. Fermentation of cocoa beans: influence of microbial activities and polyphenol concentrations on the flavour of chocolate. J Sci Food Agric (2008) 88:2288–97. 10.1002/jsfa.3349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne MJ, Hurst WJ, Miller KB, Rank C, Stuart DA. Impact of fermentation, drying, roasting and Dutch processing on epicatechin and catechin content of cocoa beans and cocoa ingredients. J Agric Food Chem (2010) 58:10518–27. 10.1021/jf102391q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan CM, Khoo W, Ye L, Lambert JD, Okeefe SF, Neilson AP. Loss of native flavanols during fermentation and roasting does not necessarily reduce digestive enzyme inhibiting bioactivities of cocoa. J Agric Food Chem (2016) 64:3616–25. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.do Carmo Brito BN, Campos Chisté R, da Silva Pena R, Abreu Gloria MB, Santos Lopes A. Bioactive amines and phenolic compounds in cocoa beans are affected by fermentation. Food Chem (2017) 228:484–90. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyi TM, Daud WRW, Mohammad AB, Samsuddin W. The kinetics of polyphenol degradation during the drying of Malaysian cocoa beans. Int J Food Sci Technol (2005) 40:323–31. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.00959.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daud WRW, Talib MZM, Kyi TM. Drying with chemical reaction in cocoa beans. Dry Technol (2007) 25:867–75. 10.1080/07373930701370241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hii CL, Law CL, Suzannah S. Drying kinetics of the individual layer of cocoa beans during heat pump drying. J Food Eng (2012) 108:276–82. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.08.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alean J, Farid C, Rojano B. Degradation of polyphenols during the cocoa drying process. J Food Eng (2016) 189:99–105. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.05.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krysiak W. Influence of roasting conditions on coloration of roasted cocoa beans. J Food Eng (2006) 77:449–53. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krysiak W. Effects of convective and microwave roasting on the physicochemical properties of cocoa beans and cocoa butter extracted from this material. Grasas Aceites (2011) 62:467–78. 10.3989/gya.114910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arlorio M, Locatelli M, Travaglia F, Coïsson JD, Del Grosso E, Minassi A. Roasting impact on the contents of clovamide (N-caffeoyl-l-DOPA) and the antioxidant activity of cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.). Food Chem (2008) 106:967–75. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu S, Kim BY, Baik MY. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant capacity of raw, roasted and puffed cacao beans. Food Chem (2016) 194:1089–94. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sacchetti G, Ioannone F, De Gregorio M, Di Mattia CD, Serafini M, Mastrocola D. Non enzymatic browning during cocoa roasting as affected by processing time and temperature. J Food Eng (2016) 169:44–52. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2015.08.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicoli MC, Toniolo R, Anese M. Relationship between redox potential and chain-breaking activity of model systems and foods. Food Chem (2004) 88:79–83. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.12.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Afoakwa EO, Paterson A, Fowler M. Factors influencing rheological and textural qualities in chocolate – a review. Trends Food Sci Technol (2007) 18:290–8. 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konar N. Influence of conching temperature and some bulk sweeteners on physical and rheological properties of prebiotic milk chocolate containing inulin. Eur Food Res Technol (2013) 236:135–43. 10.1007/s00217-012-1873-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owusu M, Petersen MA, Heimdal H. Effect of fermentation method, roasting and conching conditions on the aroma volatiles of dark chocolate. J Food Process Preserv (2012) 36:446–56. 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2011.00602.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owusu M, Petersen MA, Heimdal H. Relationship of sensory and instrumental aroma measurements of dark chocolate as influenced by fermentation method, roasting and conching conditions. J Food Sci Technol (2013) 50:909–17. 10.1007/s13197-011-0420-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bordin Schumacher AB, Brandelli A, Schumacher EW, Macedo FC, Pieta L, Klug TV. Development and evaluation of a laboratory scale conch for chocolate production. Int J Food Sci Technol (2009) 44:606–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01877.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albak F, Tekin AR. Variation of total aroma and polyphenol content of dark chocolate during three phase of conching. J Food Sci Technol (2016) 53:848–55. 10.1007/s13197-015-2036-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gültekin-Ozgüven M, Berktas I, Ozçelik B. Influence of processing conditions on procyanidin profiles and antioxidant capacity of chocolates: optimization of dark chocolate manufacturing by response surface methodology. LWT Food Sci Technol (2016) 66:252–9. 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.10.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bordiga M, Locatelli M, Travaglia F, Co JD, Mazza G. Evaluation of the effect of processing on cocoa polyphenols: antiradical activity, anthocyanins and procyanidins profiling from raw beans to chocolate. Int J Food Sci Technol (2015) 50:840–8. 10.1111/ijfs.12760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy KJ, Chronopoulos AK, Singh I, Francis MA, Moriarty H, Pike MJ, et al. Dietary flavanols and procyanidin oligomers from cocoa (Theobroma cacao) inhibit platelet function. Am J Clin Nutr (2003) 77:1466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathur S, Devaraj S, Grundy SM, Jialal I. Cocoa products decrease low density lipoprotein oxidative susceptibility but do not affect biomarkers of inflammation in humans. J Nutr (2002) 132:3663–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mursu J, Voutilainen S, Nurmi T, Rissanen TH, Virtanen JK, Kaikkonen J, et al. Dark chocolate consumption increases HDL cholesterol concentration and chocolate fatty acids may inhibit lipid peroxidation in healthy humans. Free Radic Biol Med (2004) 37:1351–9. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taubert D, Roesen R, Lehmann C, Jung N, Schomig E. Effects of low habitual cocoa intake on blood pressure and bioactive nitric oxide: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA (2007) 298:49–60. 10.1001/jama.298.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fraga CG, Actis-Goretta L, Ottaviani JI, Carrasquedo F, Lotito SB, Lazarus S, et al. Regular consumption of a flavanol-rich chocolate can improve oxidant stress in young soccer players. Clin Dev Immunol (2005) 12:11–7. 10.1080/10446670410001722159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiina Y, Funabashi N, Lee K, Murayama T, Nakamura K, Wakatsuki Y, et al. Acute effect of oral flavonoid-rich dark chocolate intake on coronary circulation, as compared with non-flavonoid white chocolate, by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography in healthy adults. Int J Cardiol (2009) 131:424–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loffredo L, Del Ben M, Perri L, Carnevale R, Nocella C, Catasca E, et al. Effects of dark chocolate on NOX-2-generated oxidative stress in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2016) 44:279–86. 10.1111/apt.13687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petrosino T, Serafini M. Antioxidant modulation of F2-isoprostanes in humans: a systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2014) 54:1202–21. 10.1080/10408398.2011.630153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serafini M, Bellocco R, Wolk A, Ekström AM. Total antioxidant potential of fruit and vegetables and risk of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology (2003) 123:985–91. 10.1053/gast.2002.35957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Serafini M, Jakszyn P, Luján-Barroso L, Agudo A, Bas Bueno-de-Mesquita H, van Duijnhoven FJ, et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and gastric cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition study. Int J Cancer (2012) 131:544–54. 10.1002/ijc.27347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miglio C, Peluso I, Raguzzini A, Villaño DV, Cesqui E, Catasta G, et al. Fruit juice drinks prevent endogenous antioxidant response to high-fat meal ingestion. Br J Nutr (2014) 111:294–300. 10.1017/S0007114513002407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Serafini M, Miglio C, Peluso I, Petrosino T. Modulation of plasma non enzymatic antioxidant capacity (NEAC) by plant foods: the role of polyphenols. Curr Top Med Chem (2011) 11:1821–46. 10.2174/156802611796235125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lettieri-Barbato D, Tomei F, Sancini A, Morabito G, Serafini M. Effect of plant foods and beverages on plasma non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity in human subjects: a meta-analysis. Br J Nutr (2013) 109:1544–56. 10.1017/S0007114513000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamora-Ros R, Serafini M, Estruch R, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Mediterranean diet and non enzymatic antioxidant capacity in the PREDIMED study: evidence for a mechanism of antioxidant tuning. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis (2013) 23:1167–74. 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]