Abstract

Diverse CRISPR-Cas systems provide adaptive immunity in many bacteria and most archaea, via a DNA-encoded, RNA-mediated, nucleic-acid targeting mechanism. Over time, CRISPR loci expand via iterative uptake of invasive DNA sequences into the CRISPR array during the adaptation process. These genetic vaccination cards thus provide insights into the exposure of strains to phages and plasmids in space and time, revealing the historical predatory exposure of a strain. These genetic loci thus constitute a unique basis for genotyping of strains, with potential of resolution at the strain-level. Here, we investigate the occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems in the genomes of various Bifidobacterium longum strains across three sub-species. Specifically, we analyzed the genomic content of 66 genomes belonging to B. longum subsp. longum, B. longum subsp. infantis and B. longum subsp. suis, and identified 25 strains that carry 29 total CRISPR-Cas systems. We identify various Type I and Type II CRISPR-Cas systems that are widespread in this species, notably I-C, I-E, and II-C. Noteworthy, Type I-C systems showed extended CRISPR arrays, with extensive spacer diversity. We show how these hypervariable loci can be used to gain insights into strain origin, evolution and phylogeny, and can provide discriminatory sequences to distinguish even clonal isolates. By investigating CRISPR spacer sequences, we reveal their origin and implicate phages and prophages as drivers of CRISPR immunity expansion in this species, with redundant targeting of select prophages. Analysis of CRISPR spacer origin also revealed novel PAM sequences. Our results suggest that CRISPR-Cas immune systems are instrumental in mounting diversified viral resistance in B. longum, and show that these sequences are useful for typing across three subspecies.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas systems, genotyping, probiotics, Bifidobacterium longum

Introduction

Bifidobacteria are one of the first commensal microorganisms that colonize the human gut, making them the dominant intestinal bacteria in infants and one of the main inhabitants in healthy adults (Arboleya et al., 2016). The alteration in the populations of bifidobacteria present in the human microbiome has been correlated with several intestinal and immunological disorders like irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), obesity, and allergy, among others (Tojo et al., 2014). The health-promoting effects of bifidobacteria consumption has shown promising results in several clinical trials for the prevention of diarrhea, reducing ulcerative colitis and IBS symptoms, and preventing necrotizing enterocolitis (Tojo et al., 2014). Among bifidobacteria, Bifidobacterium longum is the species most prevalence in healthy adults and widely commercialized in probiotic products. Probiotics were originally defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host,” (FAO/WHO., 2002; Hill et al., 2014) though a new guidance has been recently published for health claims (EFSA, 2016). Despite new regulations for health claims of probiotics, many products still misidentify the taxonomic classification of their strains based on 16S sequencing or are manufactured with low amounts of the stated microorganisms (Lewis et al., 2016; Morovic et al., 2016). In this regard, new methodologies should be applied for correct taxonomy together with internal quality control. Recently, the use of high-throughput sequencing has been suggested as a reliable methodology for correct identification (Morovic et al., 2016) as well as the use of glycolysis genes for correct taxonomy (Brandt and Barrangou, 2016).

One of the main challenges for probiotic strains is to survive the stress conditions present in the gastrointestinal tract, regarding physiological conditions (pH, bile salts, and motility) but also counteracting virus infections. The human gut constitutes a natural reservoir of phages (Stern et al., 2012), representing a huge environmental challenge for commensal and probiotic bacteria, where the need to survive constant attack has led to the need for protection against invasive DNA. One strategy that has evolved in the bacterial evolutionary arms race against foreign DNA is Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR), together with CRISPR associated (cas) genes, that constitute the adaptive immune systems in bacteria and archaea (Barrangou et al., 2007). CRISPR-Cas systems are present in bacteria and archaea and comprise effective DNA-targeting machinery against the foreign nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) of phages and plasmids (Barrangou and Doudna, 2016). CRISPR-Cas immune systems have been widely studied and characterized during the last 10 years (Barrangou and Horvath, 2017) and, to date, two different class, six different types and numerous subtypes has been described (Makarova et al., 2011, 2015; Koonin et al., 2017; Shmakov et al., 2017). CRISPR-Cas systems are present in a wide range of microorganisms and different ecological niches, from soil to food microbes, including human commensal bacteria and also pathogens, reflecting the relevance and diversity of these immune systems.

While CRISPR technology, mainly based on CRISPR-Cas9, has been used as a genetic engineering tool with incredible popularity in eukaryotes, CRISPR has tremendous potential applications in microbiology, especially engineering food microbes, starter cultures, and probiotics (Briner and Barrangou, 2016; Hidalgo-Cantabrana et al., 2017). Moreover, the repeat-spacer arrays in CRISPR loci represent a hypervariable region that can be used for genotyping and phylogenetic studies, as well as provide insights into the immunity challenges suffered by the bacteria.

In this work, we analyzed the occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems in B. longum genomes to characterize the genetic architecture of the CRISPR loci and demonstrate the potential of CRISPR-Cas systems for genotyping in this widely used probiotic species.

Materials and methods

CRISPR detection and identification

The 66 B. longum genomes (Table 1) in the GenBank database (NCBI) as of December 2016 were used to characterize the occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems in B. longum strains. The CRISPR in silico analyses were performed as follows: the CRISPR Recognition Tool (CRT; Bland et al., 2007) implemented in Geneious 10.0.6 software (Kearse et al., 2012) was used to find the repeats sequences. Then, the Cas proteins (Cas 1, Cas 3, Cas 9) previously identified in other bifidobacteria species (Briner et al., 2015) were used as template to find the Cas proteins in the query B. longum strains using BLAST algorithm (Altschul et al., 1997). Afterwards, manual curation was performed to identify and annotate the correct CRISPR-Cas systems for each strain. The CRISPR subtypes designation was performed based on the signature Cas proteins and associated ones as previously reported (Makarova et al., 2011, 2015; Koonin et al., 2017).

Table 1.

CRISPR-cas systems in Bifidobacterium longum strains.

| B. longum | Strain | Type-subtype | Repeat sequence | Repeat length | No. repeats | cas1 | cas3 | cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| longum | 7 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 159 | Y | Y | |

| 9 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 159 | Y | Y | ||

| 379 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 1 | Y | Y | ||

| 35624 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 164 | Y | Y | ||

| 105-A | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 34 | Y | Y | ||

| 1-5B | None | None | ||||||

| 1-6B | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 7 | Y | Y | ||

| 2nd locus | I-E | GGTTTATCCCCGCGTGTGCGGGGTAGAT | 28 | 21 | Y | |||

| 17-1B | I-U | CTTGCATACGTCAAAACGTATGCACTTCATTGAGGA | 36 | 44 | Y | Y | ||

| 2-2B | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 8 | Y | Y | ||

| 2nd locus | I-E | ACCTACCCCGCAGGCGCGGGGATAAA | 26 | 11 | Y | |||

| 35B | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 12 | Y | Y | ||

| 44B | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 18 | Y | Y | ||

| 2nd locus | I-E | GGTTTATCCCCGCGTGTGCGGGGTAGAT | 28 | 25 | Y | |||

| 7-1B | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 34 | Y | Y | ||

| 72B | None | None | ||||||

| AH1206 | None | None | ||||||

| ATCC55813 | None | None | ||||||

| BBMN68 | I-E | GTTTGCCCCGCATGCGCGGGGATGATCCG + | 29 | 10 | Y | Y | ||

| GTTTGCCCCGCATGCGCGGGGATGATCCG + | 29 | 13 | ||||||

| GTTTGCCCCGCACGCGCGGGGATGATCCG | 29 | 7 | ||||||

| BG7 | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 34 | Y | Y | ||

| BLO12 | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 19 | Y | Y | ||

| BXY01 | None | None | ||||||

| CCUG30698 | None | None | ||||||

| CECT 7347 | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 38 | Y | Y | ||

| CMCC P0001 | None | None | ||||||

| CMW7750 | None | None | ||||||

| D2957 | None | None | ||||||

| DJO10A | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 43 | Y | Y | ||

| DSM 20219 | None | None | ||||||

| E18 | None | None | ||||||

| EK13 | None | None | ||||||

| EK5 | None | None | ||||||

| F8 | None | None | ||||||

| GT15 | None | None | ||||||

| JCM 1217 | None | None | ||||||

| JDM 301 | None | None | ||||||

| KACC 91563 | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 33 | Y | Y | ||

| LMG 13197 | None | None | ||||||

| LO-06 | None | None | ||||||

| LO-10 | None | None | ||||||

| LO-21 | None | None | ||||||

| LO-C29 | None | None | ||||||

| LO-K29a | None | None | ||||||

| LO-K29b | None | None | ||||||

| MC-42 | I-E | GTTTGCCCCGCATGCGCGGGGATGATCCG | 29 | 136 | Y | Y | ||

| NCC2705 | None | None | ||||||

| NCIMB8809 | None | None | ||||||

| VMKB44 | II-C | CAAGCTTATCAAGAAGGGTGAATGCTAATTCCCAGC | 36 | 52 | Y | Y | ||

| infantis | 157F | None | None | |||||

| ATCC 15697 | None | None | ||||||

| BIB1401242951 | None | None | ||||||

| BIB1401272845a | None | None | ||||||

| BIB1401272845b | None | None | ||||||

| BIC1206122787 | None | None | ||||||

| BIC1307292462 | None | None | ||||||

| BIC1401111250 | None | None | ||||||

| BIC1401212621a | None | None | ||||||

| BIC1401212621b | None | None | ||||||

| BT1 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCTCACGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 33 | 61 | Y | Y | ||

| CCUG 52486 | None | None | ||||||

| CECT 7210 | None | None | ||||||

| EK3 | I-E | GTTTGCCCCGCACGCGCGGGGATGATCCG | 29 | 69 | Y | Y | ||

| 2nd locus | I-C | GTCGCACCCCTCACGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 33 | 8 | Y | |||

| IN-07 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCTCACGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 33 | 61 | Y | Y | ||

| IN-F29 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCTCACGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 33 | 76 | Y | Y | ||

| TPY12-1 | None | None | ||||||

| suis | AGR2137 | I-E | GTTTGCCCCGCACGCGCGGGGATGATCCG | 29 | 21 | Y | Y | |

| 2nd locus | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 4 | |||||

| BSM11-5 | I-C | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 62 | Y | Y | ||

| DSM 20211 | Undet | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 9 | N | |||

| LMG 21814 | Undet | GTCGCACCCCACTGGGGTGCGTGGATTGAAAT | 32 | 9 | N |

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on the amino acid sequence of Cas1, Cas2, Cas3, and Cas9 proteins, and the nucleotide sequence of the CRISPR repeats. The alignments were performed using MUSCLE algorithm (Edgar, 2004) and the trees were generated with UPGMA method (Sneath and Sokal, 1973) and 500 bootstrap replications.

Spacers analyses

CRISPR spacers were analyzed using a custom Excel Macro tool (Horvath et al., 2008) to identify similarity between strains and their divergent evolution under DNA selective pressure. Additional studies were carried out to detect similarity between the CRISPR spacers detected in B. longum and prophages sequences present in bifidobacterial chromosomes, using BLASTn analyses against 190 Bifidobacterium genomes available at GenBank database (NCBI). Protospacers and protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM; Deveau et al., 2008; Horvath et al., 2008; Mojica et al., 2009) were defined based on these analyses, and WebLogo server was used to represent the PAM sequence based on a frequency chart were the height of each nucleotide represents the conservation of that nucleotide at each position (Crooks et al., 2004). R statistics (R Development Core Team, 2008) was used to depict the heatmaps using the “ComplexHeatmap” package (Gu et al., 2016).

Results

Occurrence and diversity of CRISPR in B. longum

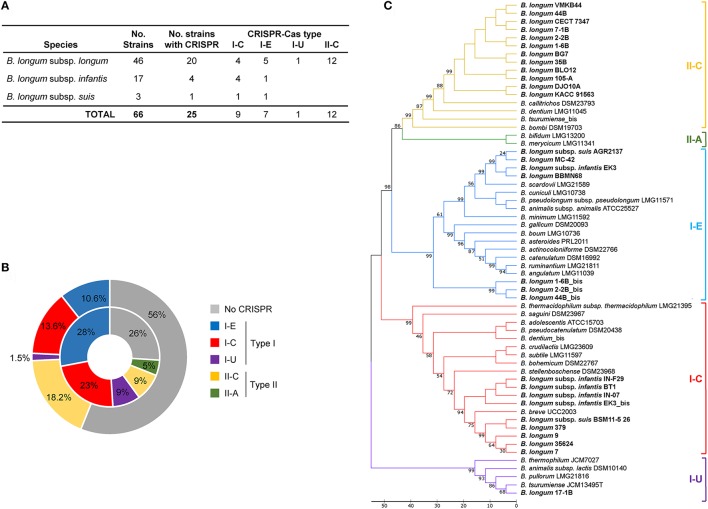

The 66 B. longum strains in GenBank were analyzed for the occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems through in silico analyses. Initially, the presence of the universal Cas1 protein was investigated to determine the presence or absence of CRISPR-Cas systems, as Cas1 is a core protein widespread across the two main classes and six main types of CRISPR-Cas systems. Over 38% of the B. longum strains (25/66) harbored cas1 genes in their genome (Table 1, Figure 1A) which is close to the 46% estimated prevalence of CRISPR in bacteria (Grissa et al., 2007). However, the occurrence of cas1 genes in bifidobacteria species was previously described to be up to 77% (Briner et al., 2015), showing a clear difference between the genus overall and the B. longum species in particular. Interestingly, the strains B. longum 1-6B, 2-2B, 44B, and B. longum subsp. infantis EK3 encoded two cas1 genes in a different region of the genome, representing a second CRISPR locus, a phenomenon that has been also described for other bifidobacteria strains like B. dentium LMG11045 (Briner et al., 2015). Overall, 29 CRISPR loci where identified in 25 strains among the three subspecies investigated, namely: B. longum subsp. longum, B. longum subsp. infantis, and B. longum subsp. suis (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

CRISPR-Cas systems in Bifidobacterium longum. Number of CRISPR-Cas systems detected in B. longum strains for each CRISPR-Cas type (A). Comparison between the occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems in B. longum strains (outside ring) and Bifidobacterium (inside ring). Percentage was calculated based on the number of positive strains for each subtype divided by total strains analyzed in each study (B). Phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid sequence of Cas1 protein of B. longum and other bifidobacteria species, aligned with MUSCLE algorithm, and depicted with UPGMA using 500 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values are recorded on the nodes. The CRISPR-Cas subtypes are written on the right and groups are colored for each subtype (C).

The CRISPR subtypes designation was performed based on the signature cas genes (cas3 for Type I and cas9 for Type II) and associated ones as previously reported for CRISPR-Cas systems classification (Makarova et al., 2011, 2015; Koonin et al., 2017). The signature cas3 and cas9 genes were identified in B. longum strains using BLAST. Overall, 12 Type II-C systems, 9 Type I-C systems, 7 Type I-E systems, and 1 Type I-U system were identified (Figure 1A). While Type I systems were detected in all three subspecies, the Type II-C selectively occurred in the B. longum subsp. longum. Moreover, CRISPR-Cas systems occurrence and diversity in B. longum highly differed from the distribution in Bifidobacterium genera (Figure 1B). Type I CRISPR-Cas systems are found in 25.7% of B. longum genomes whereas it they were found in 60% of bifidobacteria at the genus level (Figure 1B). In contrast, Type II systems are represented in 18.2% of B. longum strains, while they were only detected in 14% of the entire Bifidobacterium genus.

Regarding Type I systems, subtypes I-C, I-E, and I-U were identified in B. longum. The subtypes I-C and I-E CRISPR-Cas systems are present in the three subspecies although subtype I-C is the most common in B. longum subsp. infantis, while subtype I-E is the most prevalence in B. longum subsp. longum (Figure 1A). The CRISPR subtype I-U was only detected in B. longum 17-1B, and it is also present in other bifidobacteria like B. animalis subsp. lactis DSM10140, B. pullorum LMG21816, and B. tsurimiense JCM13495 (Briner et al., 2015). Interestingly, subtype I-U in bifidobacteria does not match the consensus previously described for CRISPR subtype I-U in other genera (Koonin et al., 2017), lacking cas8, but this genetic feature is consistent among Bifidobacterium genus.

Regarding Type II system, the subtype II-C is the only subtype present in B. longum strains, neither subtype II-A nor II-B were detected, although they are present in other bifidobacteria species (Briner et al., 2015). Noteworthy, subtype II-C was found only in the strains belonging to B. longum subsp. longum, not in subspecies infantis or suis. Indeed, subtype II-C systems is not wide-spread in bifidobacteria (Figure 1B) but it displayed high rate of occurrence in B. longum subsp. longum strains (Figure 1A).

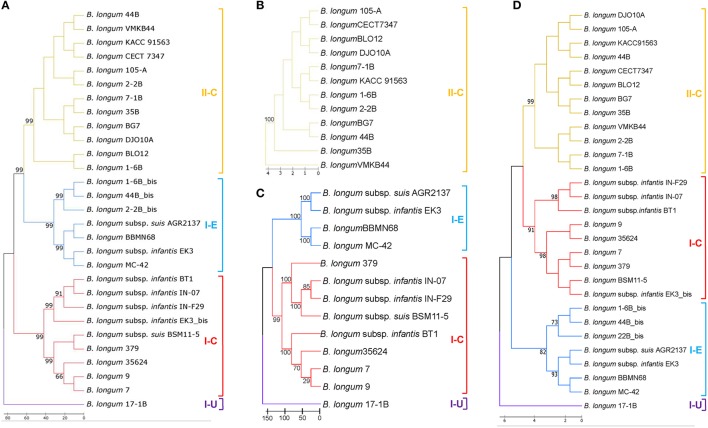

The phylogenetic analyses performed with Cas1 proteins of B. longum and other bifidobacteria species showed the divergence of the five different CRISPR subtypes present in Bifidobacterium genus grouped in four major branches (Figure 1C). Type II systems (II-A, II-C) evolved from the same branch and are phylogenetically closer to subtype I-E than subtype I-C, whereas subtype I-U is more divergent. The phylogenetic analyses based on Cas1 proteins from only B. longum strains showed three major branches encompassing the four CRISPR subtypes detected in this species (Figure 2A), with the poorly characterized subtype I-U system segregating into its own cluster. Consistently, this clustering was also obtained for Cas2 proteins (Supplementary Figure 1), Cas9, Cas3 (Figures 2B,C) and the repeats sequence (Figure 2D), confirming the co-evolutionary trends observed in CRISPR immune systems that the components of these systems co-evolve (Makarova et al., 2011; Chylinski et al., 2014).

Figure 2.

CRISPR phylogenetic analyses in B. longum. Phylogenetic tree based on the Cas1 protein of B. longum strains (A), Cas9 protein (B), Cas3 protein (C), and the CRISPR repeats sequence (D). Alignments were performed with MUSCLE algorithm and the tree was depicted with UPGMA using 500 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values are recorded on the nodes. The CRISPR-Cas subtypes are written on the right and groups are colored for each subtype.

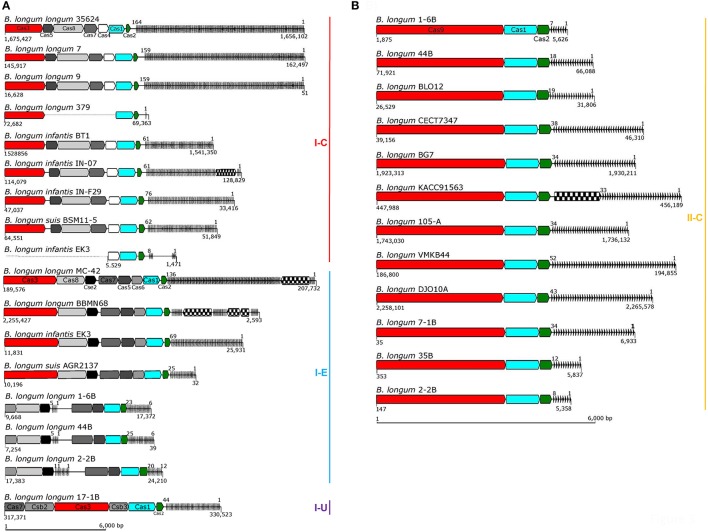

CRISPR loci characterization

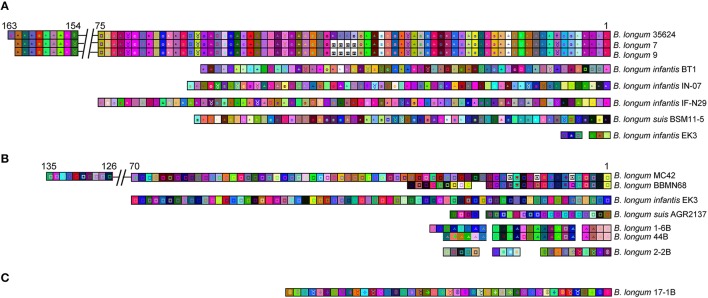

The 29 CRISPR loci present in the 25 B. longum strains were annotated after manual curation and depicted in Figure 3. Four strains harbored two different cas1 genes: B. longum 1-6B, 2-2B, 44B, and B. longum subsp. infantis EK3 (Table 1, Figure 3). In these four strains, the second cas1 gene is located in a different region of the genome, together with CRISPR repeats associated cas genes, constituting a second putative CRISPR locus (Figure 3). However, signature cas genes were absent from these second loci and the type of the locus was assigned through phylogenetic clustering of the Cas1 proteins, allowing them to be subtyped by which phylogenetic clade they belonged to (Figure 2A). When multiple loci appear in the same genome, it was observed that the CRISPR subtype I-E co-occurs with the subtype II-C in the strains B. longum 1-6B, 2-2B, and 44B, while subtype I-C co-occurs with subtype I-E in B. longum subsp. infantis EK3. The presence of two different types of CRISPR-Cas system in the same strain has been previously described for other species like B. dentium LMG11045 (subtypes II-C and I-C) and B. tsurumiense JCM13495T (subtypes II-C and I-U; Briner et al., 2015). These incomplete CRISPR loci could be the consequence of (i) a genetic reorganization, (ii) the loss of activity of these CRISPR loci toward the acquisition of the other CRISPR loci, or (iii) incomplete assemblies indicated by the draft genomes of these strains. Moreover, the strain B. longum 379 displayed a truncated CRISPR locus without accessory cas genes, neither spacers and only one repeat (Figure 3), possibly due to genome annotation troubleshooting, thereof, this strain was exclude for the next analysis.

Figure 3.

CRISPR loci in B. longum. The CRISPR locus of each strain was annotated and depicted with signature cas genes colored in red, cas3 for Type I (A) and cas9 for Type II (B), and the universal cas1 and cas2 colored in blue and green respectively. Accessory genes are colored in a gray scale regarding their functional category, CRISPR repeats are represented as black lines on the right side of each locus (spacers are not represented) and transposase are represented with checkboard pattern fill. Numbers below CRISPR-Cas systems represent their position in the genome (or contig) and the numbers on top of the repeat-spacer array represent the number of repeats. The CRISPR loci are represented according to their size, bar scale represents 6 Kb.

Regarding the size of B. longum CRISPR loci, subtypes I-C, and I-E varies from 12 to 18 Kb due to the genetic architecture involving several cas genes (multi-subunit complex Cascade) and high number of repeats (Figure 3A). Subtype II-C are the shortest loci (8 Kb), as they encompass fewer accessory cas genes and generally have a lower number of repeats (Figure 3B).

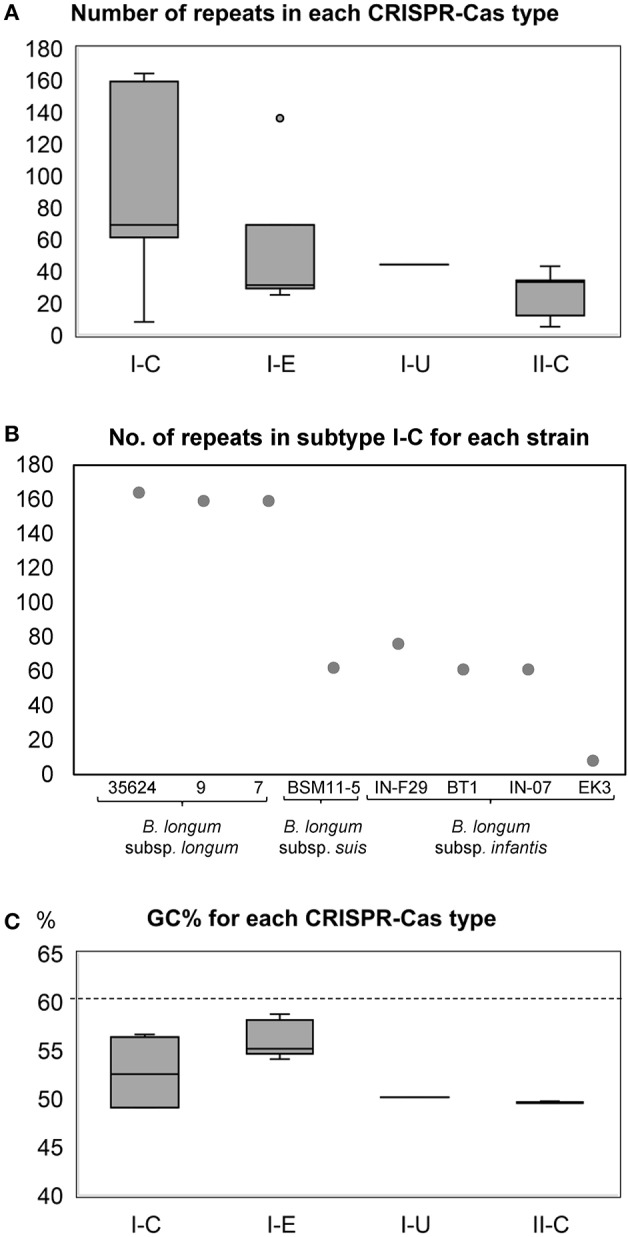

Considering the repeat-spacer array size, subtype I-C varies from 61 repeats in B. longum subsp. infantis BT1 to 164 in B. longum 35624 (Figure 4A), with the exception of B. longum subsp. infantis EK3 displaying only 8 repeats which is likely to be related with sequencing or assembly of the locus, as the cluster appears truncated (Figure 3A). The CRISPR-Cas systems from subtype I-E presents high variability in length, ranging from 25 repeats in B. longum subsp. suis AGR2137 to 136 repeats in B. longum MC-42. Subtype II-C ranges from 7 repeats in the strain B. longum 1-6B to 52 in B. longum VMKB44; and the unique subtype I-U, present in B. longum 17-1B, contains 44 repeats (Figure 4A). Interestingly the number of repeats in subtype I-C is subspecies-dependent, with incredibly higher numbers of repeats in B. longum subsp. longum and lower in B. longum subsp. infantis and subsp. suis (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Box and Whisker representation for the number of CRISPR repeats detected in the CRISPR loci of each CRISPR subtype (A). The number of CRISPR repeats in subtype I-C displayed subspecies-dependent difference between the strains of B. longum subsp. longum and B. longum subsp. infantis and B. longum subsp. suis (B). CRISPR GC content and size in B. longum. Box and Whisker representation of the GC content of the CRISPR loci of each CRISPR subtype, dotted line represent the overall GC content of whole genome in bifidobacteria (C).

The length of the repeats sequence is 32 nucleotides for subtype I-C, 29 nucleotides in subtype I-E, and 36 nucleotides for both subtype II-C and I-U. The repeat sequences are conserved within each CRISPR-Cas subtype in the same species, however the repeats of subtype I-C in B. longum subsp. infantis strains displayed 3 nucleotide polymorphisms (grew shadow in Table 1) compared to the consensus repeat sequence of subtype I-C in B. longum subsp. longum and B. longum subsp. suis (Table 1).

Noteworthy, transposases were found in the CRISPR loci at different locations: (i) interrupting the repeats-spacer array of subtype I-C (B. longum subsp. infantis IN-07) and subtype I-E (B. longum subsp. longum BBMN68 and MC42); (ii) between the universal cas2 gene and the repeat-spacer array in subtype II-C (B. longum KACC91563). Transposases are responsible for the horizontal gene transfer that frequently occurs among prokaryotes, having an enormous impact in bacterial genomic evolution (Boto, 2010). The presence of transposases in CRISPR-Cas systems may reflect the acquisition of these genetic architectures as an evolutionary advantage to survive in a complex ecological niche like the human gut. In this regard, the GC content of the CRISPR loci was analyzed for each strain and compared to the GC content of the whole genome (Table 2). While Bifidobacterium spp. genomes present a high GC content, 60% average, CRISPR loci present a GC content of 50% in CRISPR subtypes I-U and II-C (all B. longum strains), between 54 and 58% in subtype I-E and 49 and 56% in subtype I-C (Figure 4C).

Table 2.

Bifidobacterium longum strains harboring CRISPR-Cas immune systems.

| B. longum | Strain | CRISPR subtype | CRISPR locus GC% | Whole genome GC% | Origin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| longum | 7 | I-C | 49.03 | 60 | Commercial | Lewis et al., 2016 |

| 9 | I-C | 49.03 | 60 | Commercial | Lewis et al., 2016 | |

| 379 | I-C | 50.5 | 60.20 | Human gut | Averina et al., 2012 | |

| 35624 | I-C | 49.03 | 60 | Human gut | Altmann et al., 2016 | |

| 105-A | II-C | 49.56 | 60.10 | Infant feces | Kanesaki et al., 2014 | |

| 1-6B | II-C | 49.6 | 59.6 | Infant feces | Shkoporov et al., 2013 | |

| I-E | 58.11 | |||||

| 17-1B | I-U | 50.1 | 60.20 | Infant feces | Chaplin et al., 2015 | |

| 2-2B | II-C | 49.5 | 59.70 | Infant feces | Shkoporov et al., 2013 | |

| I-E | 58.7 | |||||

| 35B | II-C | 49.5 | 60.10 | Infant feces | Shkoporov et al., 2013 | |

| 44B | II-C | 49.5 | 59.7 | Infant feces | Shkoporov et al., 2013 | |

| I-E | 58.03 | |||||

| 7-1B | II-C | 49.53 | 59.80 | Infant feces | Chaplin et al., 2015 | |

| BBMN68 | I-E | 55.1 | 59.90 | Human feces | Hao et al., 2011 | |

| BG7 | II-C | 49.56 | 60.01 | Infant feces | Kwon et al., 2015 | |

| BLO12 | II-C | 49.6 | 60.00 | Infant feces | Milani et al., 2015 | |

| CECT 7347 | II-C | 49.6 | 60 | Commercial | Chenoll et al., 2013 | |

| DJO10A | II-C | 49.55 | 60.11 | Adult feces | Lee et al., 2008 | |

| KACC 91563 | II-C | 49.7 | 59.81 | Neonates feces | Ham et al., 2011 | |

| MC-42 | I-E | 55.13 | 59.80 | Infant feces | Tupikin et al., 2016 | |

| VMKB44 | II-C | 49.6 | 60.30 | Infant feces | Chaplin et al., 2015 | |

| infantis | BT1 | I-C | 49.3 | 59.4 | Infant feces | Chung, 2017 |

| EK3 | I-E | 54.6 | 59.4 | Infant feces | Chaplin et al., 2015 | |

| I-C | 55.7 | |||||

| IN-07 | I-C | 56.5 | 60.0 | Infant feces | Matsuki et al., 2016 | |

| IN-F29 | I-C | 56.6 | 59.90 | Infant feces | Matsuki et al., 2016 | |

| suis | AGR2137 | I-E | 54.6 | 59.90 | Calf feces | Kelly et al., 2016 |

| BSM11-5 | I-C | 55.8 | 59.90 | Infant feces | Bunesova et al., 2016 |

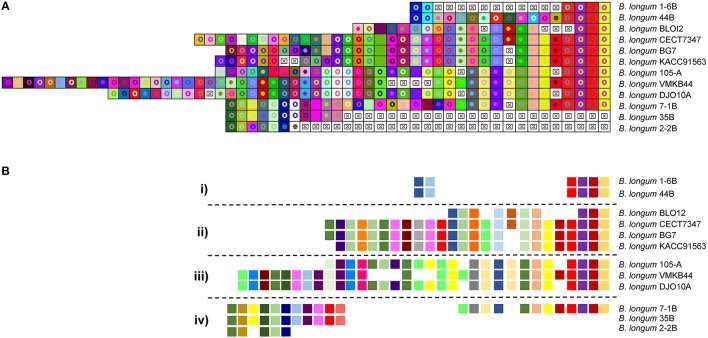

Genotyping B. longum strains through CRISPR spacers analyses

The CRISPR spacers present in B. longum were analyzed to study the similarity and divergence among the strains based on their immunity background and their evolution under selective pressure from invasive DNA. The CRISPR spacers representation was performed based on the length and nucleotide sequence of each spacer using a “macro tool;” each unique color combination is a unique spacer sequence while the internal shape indicates the length of the spacer (Horvath et al., 2008). The CRISPR-spacer content showed diversity across and within subspecies (Figures 5, 6). For instance, analysis of the spacers from subtype II-C systems in B. longum subsp. longum revealed a common origin for the 12 strains and also reflected divergent evolution into four distinct clusters based on iterative spacer acquisition events (Figure 5B). Noteworthy, cluster i includes two closely related strains, B longum 44B and 1-6B, isolated from the same Russian infant (child 1) during the first year of life and 5 years later, respectively (Shkoporov et al., 2013; Chaplin et al., 2015). These two strains share ancestral and recently acquired spacers in their type II-C CRISPR systems (Figure 5) and also in Type I-E, though there are differences in recently acquired spacers in the latest timepoint (Figure 6). Moreover, cluster iv is represented by three closely related B. longum strains isolated from the another Russian infant (child 2) at different times over 11 years, B. longum 35B, 2-2B, and 7-1B (2 year old infant, 7 years and after 11 years, respectively; Shkoporov et al., 2013; Chaplin et al., 2015). These strains showed spacer conservation over the sequenced portion of the array. Furthermore, the ancestral spacers appear conserved in other strains, suggesting common ancestry, despite the individual, spatial, and temporal differences in sampling, illustrating how stable these loci are. For instance, though B. longum BLOI2 was isolated from an infant in Italy (Milani et al., 2015), B. longum KACC91563 and BG7 were isolated from Korean infants (Ham et al., 2011; Kwon et al., 2015), B. longum 105-A from Japanese infants, B. longum VMKB44 also from a Russian child from independent studies (Chaplin et al., 2015), while B. longum DJO10A was isolated from a healthy adult in the USA (Lee et al., 2008; Table 2).

Figure 5.

CRISPR subtype II-C spacers comparison in B. longum. The CRISPR spacers of CRISPR subtype II-C were represented using an Excel Macro tool. The spacers are represented by a square and each unique spacer sequence is indicated as a unique color and a geometric figure. Squares containing an “X” represent deleted or missing spacers (A). The last spacer acquired is represented on the left side while the first spacer is on the right side. The spacers schematic representation showed a common origin (right side) for the strains and the evolution trend in four different clusters numbered from i to iv (B).

Figure 6.

CRISPR spacers array comparison in B. longum for CRISPR Type I. The CRISPR spacers of CRISPR subtypes I-C (A), subtype I-E (B), and subtype I-U (C) were represented using an Excel Macro tool. The spacers are represented by a square and each unique spacer sequence is indicated as a unique color and geometric figure. Squares containing and “X” represent deleted or missing spacers. The last spacer acquired is represented on the left side while the first spacer is on the right side. Numbers on top of the spacers array indicates the first and last spacer showing the size of the array. The long arrays were reduced for a better representation and are indicated with a double line break.

Analyses of the spacer content in subtype I-C (Figure 6A) revealed 100% identical spacers content for the strains B. longum 7 and B. longum 9 suggesting that are the same strain, or at least share the same immunity background. Also, these two strains likely evolved from the strain B. longum 35624 after an internal deletion of four spacers (Figure 6A). No spacer homology was found between B. longum subsp. infantis and B. longum subsp. suis strains harboring the CRISPR subtype I-C (Figure 6A). Again, this is another example of CRISPR spacer conservation, with subtype I-E spacers (Figure 6B) shared across strains 1-6B and 44B, which were isolated form the same infant over 6 years (Chaplin et al., 2015).

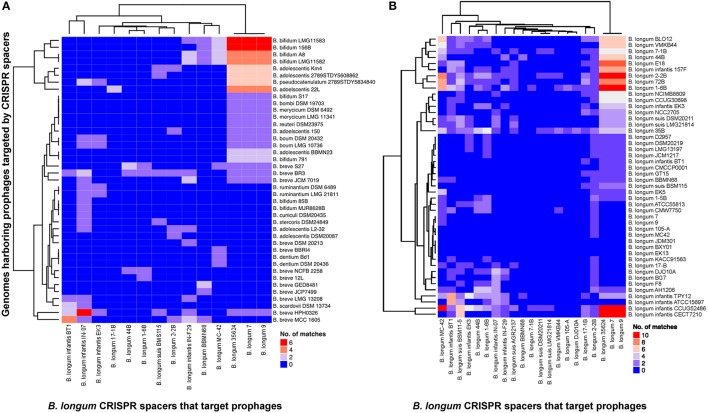

CRISPR spacers homology to prophage sequences in Bifidobacterium

Investigating the origin of the spacers elucidated information about the immunity record of each strain, documenting the challenges suffered and overcome against invasive DNA. The comparative analyses between the spacers present in the 29 CRISPR-Cas systems detected in B. longum against 190 bifidobacteria genomes revealed homology to prophages present in bifidobacterial chromosomes (Figure 7), indicating B. longum strains acquired immunity against prophages infecting other species, or possibly against lytic variants thereof. Interestingly, prophages in Bifidobacterium species were only targeted by spacers from B. longum CRISPR Type I systems (Figure 7A), where prophages in B. longum genomes where targeted by B. longum spacers from both Type I and Type II systems (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

CRISPR spacers targeting prophages in Bifidobacterium genomes. The heatmap represents B. longum CRISPR spacers that matched prophages in Bifidobacterium genomes (A) and B. longum genomes (B). The vertical axis represent the genomes that harbor prophages targeted by B. longum CRISPR spacers. The horizontal axis represent B. longum strains carrying CRISPR spacers that target prophages. The color scales represents the number of targeting events with blue squares representing the absent of matches and red squares representing the highest number of targeting.

From the 25 B. longum strains harboring CRISPR-Cas systems, 14 strains presented at least one spacer targeting a prophage in Bifidobacteirum genomes (Figures 7, 8). The CRISPR-Cas systems of the strains B. longum 35624, 7 and 9 contain the higher number of spacers targeting prophages in Bifidobacterium spp. genomes being Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Bifidobacterium breve the species most frequently targeted by CRISPR spacers of B. longum (Figure 7A). Moreover the strains B. longum 35624, 7 and 9 present also the higher number of spacers that match other B. longum genomes (Figure 7B) with B. longum subsp. infantis CCUG4286, CECT7210, B. longum subsp. longum 2-2B and 1-6B the strains most targeted (Figure 7B).

Figure 8.

B. bifidum LMG11583 prophage targeted by B. longum spacers and PAM prediction for subtype I-C. The prophage integrated in B. bifidum LMG11583 chromosome is targeted by several CRISPR spacers, from B. longum subsp. longum and B. longum subsp. infantis, each unique spacer represented with a unique color, and the CRISPR-Cas subtype between brackets (A). The figure on the bottom left shows the protospacer sequence of the prophage matched by each spacer (color legend) and the upstream region containing the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) underlined, whereas bottom right displayed the consensus PAM represented with the frequency plot of WebLogo server (B).

Regarding the diversity of the species matched by B. longum spacers, B. longum subsp. longum targeted prophages in up to nine different bifidobacteria species, B. longum subsp. infantis spacers targeted up to 10, whereas B. longum subsp. suis targeted only four different species (Figures 7, 8). The three B. longum subspecies matched prophages present in B. adolescentis, B. breve, and B. longum and differed in the other bifidobacterial species targeted (Figure 7A).

The strain B. bifidum LMG11583 present the most targeted prophage by B. longum spacers, with a total of 22 matched from nine unique spacers, from six different strains belonging to B. longum and B. longum subsp. infantis (Figure 8). Noteworthy, the strains B. longum 7, 9, 35624 present the same six spacers matching the prophage in relatively close regions of the major capsid protein and in the DNA packaging machinery components, like the portal protein and the HNH endonuclease. The portal protein plays a critical role in head assembly, genome packaging, tail attachment, and genome injection (Sun L. et al, 2015) whereas the NHN is a crucial component of the terminase packaging reaction, which is involved in packaging double-stranded DNA bacteriophage into a prohead protein (Kala et al., 2014). Thereof, the cleavage of these prophage vital components through CRISPR immune systems will prevent prophage replication and the bacteria will survive.

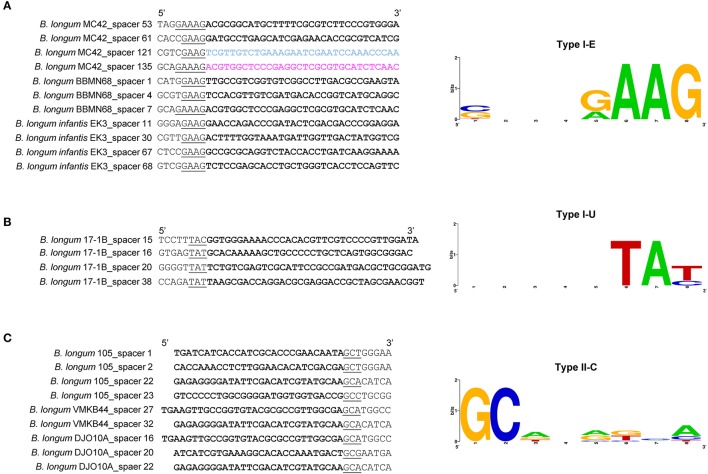

The analysis of the protospacers, the spacer sequence in the targeted DNA, together with the upstream (5′-end) and downstream (3′-end) region allowed us to define the protospacers adjacent motif (PAM; Deveau et al., 2008; Horvath et al., 2008; Mojica et al., 2009), that is absolutely necessary for DNA binding through CRISPR-Cas systems (Sternberg et al., 2014). The PAM is located immediately adjacent to the protospacer, typically at the 5′ end for Type I systems, and at the 3′ end for Type II systems, and represents a signature nucleotide sequence associated with each cas nuclease or effector complex. In this regard, different PAM sequences were identified for each CRISPR subtypes present in B. longum (Figure 9). The PAM for subtypes I-C was defined as 5′-TTC-3′, whereas the PAM for subtypes I-E was defined as 5′-NAAG-3′, and the PAM for subtype I-U was 5′-TAN-3′. Type II systems are only represented by subtype II-C in B. longum and the identified PAM was 5′-GCN-3′. The Cas9 identified in the twelve B. longum strains are 99% identical (data not shown), and therefore predicted to recognize the same PAM sequence (Figure 9). The highly conserved sequence for Cas9 in B. longum is also in concordance with the common origin defined for the 12 strains based on the spacers genotyping (Figure 5), and it also may reflect that these CRISPR-Cas systems are still active. The PAM identified for B. longum subtype II-C systems highly differs from the PAM defined for subtype II-C in B. bombi, 5′-NNG-3′, and from subtype II-A in B. merycicum 5′-NGG-3′ reflecting that Cas9 is not conserved among the different species and neither is the PAM it recognizes. Altogether, this is the first time that the CRISPR loci and the PAM has been identified for the probiotic species B. longum, opening new avenues for repurposing the endogenous CRISPR-Cas systems, possibly for genome editing to enhance probiotic features of these bacteria, to promote human health (Hidalgo-Cantabrana et al., 2017).

Figure 9.

PAM prediction for B. longum CRISPR-Cas systems. PAM prediction for the CRISPR-Cas subtypes I-E (A), I-U (B), and II-C (C) present in B. longum. The left panel displayed the protospacers in bold, and the 5′-end or 3′-end (Type I and Type II respectively) containing the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) underlined. The right panel displayed the consensus PAM represented with the frequency plot of WebLogo server.

Discussion

B. longum genomes showcase extensive diversity in their CRISPR-Cas systems, with variability among the three investigated subspecies (longum, infantis, and suis). Four different subtypes, belonging to Type I and Type II were detected in B. longum strains. Interestingly, Type I systems are present in the subspecies B. longum subsp. longum, B. longum subsp. infantis, and B. longum subsp. suis, although the Type II system was only detected in B. longum subsp. longum and only represented by subtype II-C. The presence of subtype II-C in B. longum was previously described for the strain DJO10A (Horvath et al., 2009) although it was not found in a large data set with other species of bifidobacteria (Briner et al., 2015), mainly due to the use of a unique strain as a representative of each species. Type II systems are the least common systems in nature (Makarova et al., 2015) and also in bifidobacteria (Briner et al., 2015), but it represents the highest occurrence in B. longum strains, although is a strain dependent characteristic and not a general feature. Noteworthy, this report showed that in bifidobacteria some of the CRISPR characteristics might be subspecies dependent, like the number of repeats and the repeat sequence, as they were different in B. longum subsp. infantis strains. A low number of repeats-spacers may reflect lower bacterial challenges against invasive DNA. The lower number of spacers detected in the CRISPR subtype I-C of B. longum subsp. infantis strains, isolated from infant feces, and high number of spacers in B. longum subsp. longum strains isolated from adult feces (Table 2), represent timing associated bacterial challenges and spacers acquisition.

The CRISPR spacer analysis of B. longum strains harboring the CRISPR subtype II-C allowed genotyping and evolutionary studies. The repeat-spacer array provided a hyper-variable region that could be used for genotyping purpose. The spacers displayed a common origin for all the strains suggesting they evolve from the same ancestor into four different clusters under selective pressure of invasive DNA. The spacers sequences present in the CRISPR-Cas systems of B. longum can be used as a genetic bar code for genotyping, showing a powerful mechanism for traceability of probiotics. The correct identification of each strains is instrumental to track select strains, to avoid misidentification, as well as to monitor and deter the potential use by competitors. This is indeed a convenient and powerful tool for the food industry to monitor and track the use and distribution of starter cultures and probiotics. Furthermore, spacer conservation in strains isolated in differences instances across individuals, location and time provides a basis for tracking genotypes with high-resolution and accuracy.

Regarding B. longum strains, the correct identification and taxonomy has been a problem given the genetic similarity between and within the subspecies B. longum subsp. longum and B. longum subsp. infantis (Lugli et al., 2014; Milani et al., 2014). In this regard, new genetic approaches have been proposed for high-resolution strain identification of closely related species of bifidobacteria, based on multiplex PCR primers targeting the core and variable genes (Ferrario et al., 2015) or based on terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (Lewis et al., 2013). Recently, Lewis and co-workers showed that 15 of 16 commercial probiotic products present a bacterial composition that differ from the ingredient list, sometimes at a subspecies level (Lewis et al., 2016). Similarly, in an independent study, Morovic and co-workers showed that 42% of the commercial dietary supplements contained incorrect labeled microorganism regarding taxonomy, and 33% were below the CFU level claim (Morovic et al., 2016). Thus, alternative methodologies for genotyping and correct identification should be used in addition to traditional tools. CRISPR-Cas systems have been used for identifying: (i) industrial microbes, including: Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus casei, and Lactobacillus paracasei (Horvath et al., 2008; Broadbent et al., 2012; Smokvina et al., 2013), (ii) food pathogens: Lactobacillus buchneri (Briner and Barrangou, 2014) and (iii) human pathogens: Campilobacter jejuni (Kovanen et al., 2014), Clostridium difficile (Andersen et al., 2016), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Sola et al., 2015; Freidlin et al., 2017), Salmonella enterica (Shariat et al., 2013, 2015; Bachmann et al., 2014; Almeida et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2017), Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Sun H. et al., 2015), Yersinia pestis (Barros et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2017) and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (Koskela et al., 2015), among others. However, genotyping through CRISPR technologies has been seldom applied to probiotics, with few exceptions in Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Douillard et al., 2013) and Lactobacillus gasseri (Sanozky-Dawes et al., 2015). Thus, we suggest the use of CRISPR spacers as a genetic tool for genotyping B. longum, the most widely used probiotic species for human consumption, especially for evolutionary studies in closely related strains. However, the use of CRISPR spacers for genotyping is limited to the strains that harbor CRISPR-Cas systems in their genome.

CRISPR spacers represent the immunity record of the strain and the environmental challenges suffered with invasive DNA. In this report, we showed that B. longum strains displayed CRISPR spacers targeting prophages present in the genome of several bifidobacterial species. These findings are in accordance with previous reported data of prophages in the genus Bifidobacterium (Ventura et al., 2009; Briner et al., 2015; Lugli et al., 2016) recently named as bifidophages (Duranti et al., 2017). The high number of spacers matching prophages integrated in other bifidobacterial strains suggest that those species inhabit the same ecological niche where a co-evolution between CRISPR immune systems and prophage has occurred. The presence of CRISPR spacers in B. longum against certain Bifidobacterium spp. showed evidence of CRISPR to cause speciation, whereas the spacers matching prophages in other B. longum strains displayed evidence of prophage specificity. In addition, the presence of a high number of spacers in B. longum strains reinforce that the human gut, the main B. longum ecological niche, is a phage rich environment. In this sense, the human gut microbiome has been reported as a natural phage reservoir (Stern et al., 2012) where CRISPR-Cas immune systems has been detected across the human microbiome metagenomics data (Gogleva et al., 2014) and also in the oral microbiome (Wang et al., 2016). In this regard, CRISPR-Cas systems will confer an evolutionary advantage as a defense system to survive, avoiding predation by prophages and invasive DNA. Because of this, B. longum strains harboring CRISPR-Cas systems will be suitable probiotic candidates due to their survival capability against virus challenges based on CRISPR-Cas immune systems, ensuring their viability in the human gut and their traceability based on the spacer sequences.

Upon the characterization of CRISPR-Cas immune systems in B. longum, together with PAM identification, new avenues for genome engineering of next-generation probiotics are open. CRISPR technologies have led to a wide range of applications in a wide variety of organisms, although prokaryotes genome editing through CRISPR has been arguably poorly exploited to date (Hidalgo-Cantabrana et al., 2017). Genome engineering can be performed by delivering the precise, programmable and portable Cas9 nuclease in a plasmid (exogenous system) together with a single guide RNA (Jinek et al., 2012) or by repurposing the endogenous CRISPR systems of the bacteria that encode active systems, delivering self-targeting templates with a guide RNA or a CRISPR array. Briner and co-workers suggest that the CRISPR immune systems of bifidobacteria are likely active, based on preliminary transcriptomic data and complete functional CRISPR loci (Briner et al., 2015). Thus, repurposing the endogenous CRISPR-Cas systems of bifidobacteria in general, and B. longum in particular, provides an excellent opportunity to carry out genome editing in recalcitrant strains that are otherwise cumbersome to genetically manipulate with classical methods. Nonetheless, CRISPR technologies open new avenues to perfect probiotic bacteria and food microbes, to enhance their probiotic features, to improve their survival capability under stress conditions, or to increase their ability to modulate host immune response and impact human health.

Conclusions

B. longum encode a diversity of CRISPR-Cas immune systems, belonging to four different subtypes, with large and diverse repeat-spacer arrays, indicating that these systems are likely active and protective against invasive DNA. Analysis of CRISPR spacer origin suggests adaption of this probiotic species to the human gut phage environment. Furthermore, CRISPR locus diversity shows potential for precise genotyping. The characterization of CRISPR-Cas immune systems in B. longum provides opportunities to develop genome editing tools using the endogenous systems for the development of next-generation probiotic bacteria.

Author contributions

CH designed the study, performed analyses and wrote the manuscript. CH and AC performed bioinformatics analyses. RB and BS participated, coordinated, and supervised the study. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

RB and AC are co-inventors on several patents related to CRISPR-Cas systems and their uses. RB is a co-founder and SAB member of Intellia Therapeutics and Locus Biosciences. CH and BS are on the scientific advisory board and co-founder of Microviable Therapeutics. The other author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues and support from NC State University. CH thanks to FEMS and EMBO for the Research Grants.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was funded by start-up funds from North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Ag Foundation.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01851/full#supplementary-material

Phylogenetic tree based on the Cas2 protein of B. longum strains. Alignments were performed with MUSCLE algorithm and the tree was depicted with UPGMA using 500 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values are recorded on the nodes. The CRISPR-Cas subtypes are written on the right and groups are colored for each subtype.

References

- Almeida F., Medeiros M. I., Rodrigues D. D., Allard M. W., Falcao J. P. (2017). Molecular characterization of Salmonella typhimurium isolated in Brazil by CRISPR-MVLST. J. Microbiol. Methods 133, 55–61. 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann F., Kosma P., O'Callaghan A., Leahy S., Bottacini F., Molloy E., et al. (2016). Genome analysis and characterisation of the Exopolysaccharide produced by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum 35624. PLoS ONE 11:e0162983. 10.1371/journal.pone.0162983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. M., Shoup M., Robinson C., Britton R., Olsen K. E., Barrangou R. (2016). CRISPR diversity and microevolution in Clostridium difficile. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 2841–2855. 10.1093/gbe/evw203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arboleya S., Watkins C., Stanton C., Ross R. P. (2016). Gut Bifidobacteria populations in human health and aging. Front. Microbiol. 7:1204. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averina O. V., Nezametdinova V. Z., Alekseeva M. G., Danilenko V. N. (2012). Genetic instability of probiotic characteristics in the Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum B379M strain during cultivation and maintenance. Russian J. Genet. 48, 1103–1111. 10.1134/S1022795412110026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann N. L., Petty N. K., Ben Zakour N. L., Szubert J. M., Savill J., Beatson S. A. (2014). Genome analysis and CRISPR typing of Salmonella enterica serovar Virchow. BMC Genomics 15:389. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Doudna J. A. (2016). Applications of CRISPR technologies in research and beyond. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 933–941. 10.1038/nbt.3659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Horvath P. (2017). A decade of discovery: CRISPR functions and applications. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17092. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Fremaux C., Deveau H., Richards M., Boyaval P., Moineau S., et al. (2007). CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712. 10.1126/science.1138140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros M. P., Franca C. T., Lins R. H., Santos M. D., Silva E. J., Oliveira M. B., et al. (2014). Dynamics of CRISPR loci in microevolutionary process of Yersinia pestis strains. PLoS ONE 9:e108353. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland C., Ramsey T. L., Sabree F., Lowe M., Brown K., Kyrpides N. C., et al. (2007). CRISPR recognition tool (CRT): a tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinformatics 8:209. 10.1186/1471-2105-8-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boto L. (2010). Horizontal gene transfer in evolution: facts and challenges. Proc. Biol. Sci. 277, 819–827. 10.1098/rspb.2009.1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K., Barrangou R. (2016). Phylogenetic analysis of the Bifidobacterium genus using glycolysis enzyme sequences. Front. Microbiol. 7:657. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briner A. E., Barrangou R. (2014). Lactobacillus buchneri genotyping on the basis of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) locus diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 994–1001. 10.1128/AEM.03015-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briner A. E., Barrangou R. (2016). Deciphering and shaping bacterial diversity through CRISPR. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 31, 101–108. 10.1016/j.mib.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briner A. E., Lugli G. A., Milani C., Duranti S., Turroni F., Gueimonde M., et al. (2015). Occurrence and diversity of CRISPR-cas systems in the genus Bifidobacterium. PLoS ONE 10:e0133661. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent J. R., Neeno-Eckwall E. C., Stahl B., Tandee K., Cai H., Morovic W., et al. (2012). Analysis of the Lactobacillus casei supragenome and its influence in species evolution and lifestyle adaptation. BMC Genomics 13:533. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunesova V., Lacroix C., Schwab C. (2016). Fucosyllactose and L-fucose utilization of infant Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense. BMC Microbiol. 16, 248. 10.1186/s12866-016-0867-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin A. V., Efimov B. A., Smeianov V. V., Kafarskaia L. I., Pikina A. P., Shkoporov A. N. (2015). Intraspecies genomic diversity and long-term persistence of Bifidobacterium longum. PLoS ONE 10:e0135658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenoll E. C. F., Silva A., Ibáñez A., Martinez-Blanch J. F., Bollati-Fogolín M., Crispo M., et al. (2013). Genomic sequence and pre-clinical safety assessment of Bifidobacterium longum CECT 7347, a probiotic able to reduce the toxicity and inflammatory potential of Gliadin-derived peptides. J. Probiotics Health 1:106 10.4172/2329-8901.1000106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M. J. (2017). Bifidobacterium Longum cbt bg7 Strain and Functional Food Composition Containing Same for Promoting Growth. Google Patents. WO2016186245A1.

- Chylinski K., Makarova K. S., Charpentier E., Koonin E. V. (2014). Classification and evolution of type II CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 6091–6105. 10.1093/nar/gku241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004). WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190. 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau H., Barrangou R., Garneau J. E., Labonte J., Fremaux C., Boyaval P., et al. (2008). Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1390–1400. 10.1128/JB.01412-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douillard F. P., Ribbera A., Kant R., Pietila T. E., Jarvinen H. M., Messing M., et al. (2013). Comparative genomic and functional analysis of 100 Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains and their comparison with strain GG. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003683. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranti S., Lugli G. A., Mancabelli L., Armanini F., Turroni F., James K., et al. (2017). Maternal inheritance of bifidobacterial communities and bifidophages in infants through vertical transmission. Microbiome 5, 66. 10.1186/s40168-017-0282-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (2016). Guidance on the scientific requirements for health claims related to the immune system, the gastrointestinal tract and defence against pathogenic microorganisms. EFSA J. 14, 23 10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO (2002). Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Available online at: http://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf

- Ferrario C., Milani C., Mancabelli L., Lugli G. A., Turroni F., Duranti S., et al. (2015). A genome-based identification approach for members of the genus Bifidobacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91. 10.1093/femsec/fiv009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidlin P. J., Nissan I., Luria A., Goldblatt D., Schaffer L., Kaidar-Shwartz H., et al. (2017). Structure and variation of CRISPR and CRISPR-flanking regions in deleted-direct repeat region Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. BMC Genomics 18:168. 10.1186/s12864-017-3560-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogleva A. A., Gelfand M. S., Artamonova I. I. (2014). Comparative analysis of CRISPR cassettes from the human gut metagenomic contigs. BMC Genomics 15:202. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I., Vergnaud G., Pourcel C. (2007). CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W52–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkm360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z., Eils R., Schlesner M. (2016). Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham J. S., Lee T., Byun M. J., Lee K. T., Kim M. K., Han G. S., et al. (2011). Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum KACC 91563. J. Bacteriol. 193, 5044. 10.1128/JB.05620-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Huang D., Guo H., Xiao M., An H., Zhao L., et al. (2011). Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum BBMN68, a new strain from a healthy chinese centenarian. J. Bacteriol. 193, 787–788. 10.1128/JB.01213-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Cantabrana C., O'Flaherty S., Barrangou R. (2017). CRISPR-based engineering of next-generation lactic acid bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 37, 79–87. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C., Guarner F., Reid G., Gibson G. R., Merenstein D. J., Pot B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P., Coute-Monvoisin A. C., Romero D. A., Boyaval P., Fremaux C., Barrangou R. (2009). Comparative analysis of CRISPR loci in lactic acid bacteria genomes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 131, 62–70. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P., Romero D. A., Coute-Monvoisin A. C., Richards M., Deveau H., Moineau S., et al. (2008). Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1401–1412. 10.1128/JB.01415-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., Charpentier E. (2012). A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821. 10.1126/science.1225829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kala S., Cumby N., Sadowski P. D., Hyder B. Z., Kanelis V., Davidson A. R., et al. (2014). HNH proteins are a widespread component of phage DNA packaging machines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 6022–6027. 10.1073/pnas.1320952111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanesaki Y., Masutani H., Sakanaka M., Shiwa Y., Fujisawa T., Nakamura Y., et al. (2014). Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum 105-A, a strain with high transformation efficiency. Genome Announc. 2:e01311-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01311-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., et al. (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W. J., Cookson A. L., Altermann E., Lambie S. C., Perry R., Teh K. H., et al. (2016). Genomic analysis of three Bifidobacterium species isolated from the calf gastrointestinal tract. Sci. Rep. 6:30768. 10.1038/srep30768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E. V., Makarova K. S., Zhang F. (2017). Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 37, 67–78. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskela K. A., Mattinen L., Kalin-Manttari L., Vergnaud G., Gorge O., Nikkari S., et al. (2015). Generation of a CRISPR database for Yersinia pseudotuberculosis complex and role of CRISPR-based immunity in conjugation. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 4306–4321. 10.1111/1462-2920.12816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovanen S. M., Kivisto R. I., Rossi M., Hanninen M. L. (2014). A combination of MLST and CRISPR typing reveals dominant Campylobacter jejuni types in organically farmed laying hens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117, 249–257. 10.1111/jam.12503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S. K., Kwak M. J., Seo J. G., Chung M. J., Kim J. F. (2015). Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum KCTC 12200BP, a probiotic strain promoting the intestinal health. J. Biotechnol. 214, 169–170. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Karamychev V. N., Kozyavkin S. A., Mills D., Pavlov A. R., Pavlova N. V., et al. (2008). Comparative genomic analysis of the gut bacterium Bifidobacterium longum reveals loci susceptible to deletion during pure culture growth. BMC Genomics 9:247. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Z. T., Bokulich N. A., Kalanetra K. M., Ruiz-Moyano S., Underwood M. A., Mills D. A. (2013). Use of bifidobacterial specific terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms to complement next generation sequence profiling of infant gut communities. Anaerobe 19, 62–69. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Z. T., Shani G., Masarweh C. F., Popovic M., Frese S. A., Sela D. A., et al. (2016). Validating bifidobacterial species and subspecies identity in commercial probiotic products. Pediatr. Res. 79, 445–452. 10.1038/pr.2015.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli G. A., Milani C., Turroni F., Duranti S., Ferrario C., Viappiani A., et al. (2014). Investigation of the evolutionary development of the genus Bifidobacterium by comparative genomics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6383–6394. 10.1128/AEM.02004-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli G. A., Milani C., Turroni F., Tremblay D., Ferrario C., Mancabelli L., et al. (2016). Prophages of the genus Bifidobacterium as modulating agents of the infant gut microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2196–2213. 10.1111/1462-2920.13154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Haft D. H., Barrangou R., Brouns S. J., Charpentier E., Horvath P., et al. (2011). Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 467–477. 10.1038/nrmicro2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Alkhnbashi O. S., Costa F., Shah S. A., Saunders S. J., et al. (2015). An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 722–736. 10.1038/nrmicro3569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T., Yahagi K., Mori H., Matsumoto H., Hara T., Tajima S., et al. (2016). A key genetic factor for fucosyllactose utilization affects infant gut microbiota development. Nat. Commun. 7:11939. 10.1038/ncomms11939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani C., Lugli G. A., Duranti S., Turroni F., Bottacini F., Mangifesta M., et al. (2014). Genomic encyclopedia of type strains of the genus Bifidobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6290–6302. 10.1128/AEM.02308-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani C., Mancabelli L., Lugli G. A., Duranti S., Turroni F., Ferrario C., et al. (2015). Exploring vertical transmission of Bifidobacteria from mother to child. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 7078–7087. 10.1128/AEM.02037-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica F. J., Diez-Villasenor C., Garcia-Martinez J., Almendros C. (2009). Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology 155(Pt 3), 733–740. 10.1099/mic.0.023960-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morovic W., Hibberd A. A., Zabel B., Barrangou R., Stahl B. (2016). Genotyping by PCR and high-throughput sequencing of commercial probiotic products reveals composition biases. Front. Microbiol. 7:747. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanozky-Dawes R., Selle K., O'Flaherty S., Klaenhammer T., Barrangou R. (2015). Occurrence and activity of a type II CRISPR-Cas system in Lactobacillus gasseri. Microbiology 161, 1752–1761. 10.1099/mic.0.000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariat N., Sandt C. H., DiMarzio M. J., Barrangou R., Dudley E. G. (2013). CRISPR-MVLST subtyping of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars Typhimurium and Heidelberg and application in identifying outbreak isolates. BMC Microbiol. 13:254. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariat N., Timme R. E., Pettengill J. B., Barrangou R., Dudley E. G. (2015). Characterization and evolution of Salmonella CRISPR-Cas systems. Microbiology 161, 374–386. 10.1099/mic.0.000005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkoporov A. N., Efimov B. A., Khokhlova E. V., Chaplin A. V., Kafarskaya L. I., Durkin A. S., et al. (2013). Draft genome sequences of two pairs of human intestinal Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strains, 44B and 1-6B and 35B and 2-2B, consecutively isolated from two children after a 5-Year time period. Genome Announc. 1:e00234-13. 10.1128/genomeA.00234-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Smargon A., Scott D., Cox D., Pyzocha N., Yan W., et al. (2017). Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 169–182. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokvina T., Wels M., Polka J., Chervaux C., Brisse S., Boekhorst J., et al. (2013). Lactobacillus paracasei comparative genomics: towards species pan-genome definition and exploitation of diversity. PLoS ONE 8:e68731. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath P. H., Sokal R. R. (1973). Numerical Taxonomy. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sola C., Abadia E., Le Hello S., Weill F. X. (2015). High-throughput CRISPR typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and Salmonella enterica Serotype Typhimurium. Methods Mol. Biol. 1311, 91–109. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2687-9_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern A., Mick E., Tirosh I., Sagy O., Sorek R. (2012). CRISPR targeting reveals a reservoir of common phages associated with the human gut microbiome. Genome Res. 22, 1985–1994. 10.1101/gr.138297.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. H., Redding S., Jinek M., Greene E. C., Doudna J. A. (2014). DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67. 10.1038/nature13011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Li Y., Shi X., Lin Y., Qiu Y., Zhang J., et al. (2015). Association of CRISPR/Cas evolution with Vibrio parahaemolyticus virulence factors and genotypes. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 12, 68–73. 10.1089/fpd.2014.1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Zhang X., Gao S., Rao P. A., Padilla-Sanchez V., Chen Z., et al. (2015). Cryo-EM structure of the bacteriophage T4 portal protein assembly at near-atomic resolution. Nat. Commun. 6, 7548. 10.1038/ncomms8548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2008). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Tojo R., Suarez A., Clemente M. G., de los Reyes-Gavilan C. G., Margolles A., Gueimonde M., et al. (2014). Intestinal microbiota in health and disease: role of bifidobacteria in gut homeostasis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 15163–15176. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupikin A. E., Kalmykova A. I., Kabilov M. R. (2016). Draft genome sequence of the probiotic Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strain MC-42. Genome Announc. 4:e01411-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01411-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura M., Turroni F., Lima-Mendez G., Foroni E., Zomer A., Duranti S., et al. (2009). Comparative analyses of prophage-like elements present in bifidobacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6929–6936. 10.1128/AEM.01112-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Gao Y., Zhao F. (2016). Phage-bacteria interaction network in human oral microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2143–2158. 10.1111/1462-2920.12923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Hu Y., Xu Y., Yin K., Li Y., Chen Y., et al. (2017). Genetic analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum biovar Pullorum based on characterization and evolution of CRISPR sequence. Vet. Microbiol. 203, 81–87. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. Q., Xin Y. Q., Li X., Zhang Q. W., Yang X. Y., Jin Y., et al. (2017). [Genotyping by CRISPR and regional distribution of Yersinia pestis in Qinghai-plateau from 1954 to 2011]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 51, 237–242. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic tree based on the Cas2 protein of B. longum strains. Alignments were performed with MUSCLE algorithm and the tree was depicted with UPGMA using 500 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values are recorded on the nodes. The CRISPR-Cas subtypes are written on the right and groups are colored for each subtype.