Abstract

Depression in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) is highly prevalent and related to worse adherence to antiretroviral therapy, but is amenable to change via CBT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) specifically addresses negative automatic thoughts (ATs) as one component of the treatment. There is little research on the temporal nature of the relation between ATs and depression. HIV-positive adults with depression (N=240) were randomized to CBT-AD, information/supportive psychotherapy for adherence and depression (ISP-AD), or one session of adherence counseling alone (ETAU). ATs were self-reported (Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire; ATQ) and depression was assessed by blinded interview (Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MADRS) at baseline, and 4-, 8-, and 12-months. We performed autoregressive cross-lagged panel models. Broadly, decreases in ATs were followed by decreases in depression, but decreases in depression were not followed by decreases in ATs. In CBT-AD, decreases in ATs were followed by decreases in depression, and vice versa. However, in the ISP group, while depression and ATs both significantly influenced each other, not all relations were in the direction expected. This study adds to the evidence base for cognitive interventions to decrease depression in individuals with a chronic medical condition, HIV/AIDS.

Depression in people living with chronic medical illnesses has a higher prevalence than in medically healthy individuals (Moussavi et al. 2007), and is associated with worse self-care behaviors (DiMatteo et al. 2000; Gonzalez et al. 2008; Gonzalez et al. 2011). In people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), rates are as high as 37% in various studies (Asch et al. 2003; Atkinson and Grant 1994; Bing et al. 2001; Ciesla and Roberts 2001; Dew et al. 1997). Depression in PLWHA is associated with poorer disease course and worse health risk behaviors (Safren et al. 2009). For example, PLWHA with depression exhibit a more rapid decline in CD4 cells, faster HIV viral load increase, faster progression to AIDS (Horberg et al. 2008; Ironson et al. 2005; Leserman 2008), as well as increased substance use (Pence et al. 2006; Tegger et al. 2008), more risky sexual behavior (Kelly and Amirkhanian 2003; O’Cleirigh et al. 2013; Shrier et al. 2001), and, importantly, poor adherence to antiretroviral medication (Gonzalez et al. 2011; Uthman et al. 2014).

Fortunately, depression in PLWHA is amenable to change via psychotherapeutic interventions, especially cognitive behavioral therapies (Brown et al. 2016; see Olatunji et al. 2006 for a review). One evidenced-based approach, cognitive-behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD), has a growing evidence base in individuals with chronic illness, such as in PLWHA (Brown et al. 2016; Safren et al. 2009, 2012, 2016; Simoni et al. 2013) and diabetes (Safren et al. 2014), despite its challenges in application (Simoni et al. 2011). CBT-AD contains interventions that specifically address medication adherence and, for depression, modules for behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring with a particular focus on negative automatic thoughts (ATs), problem-solving, and relaxation training.

Negative ATs are repetitive thoughts that contain themes of personal loss or failure (Hollon and Kendall 1980; Smith and Alloy 2009). Previous research has shown that ATs and depressive symptoms are correlated, and posit that they likely influence each other to maintain depression (Kwon and Oei 1992; Moorey 2010). One study has shown that ATs decreased pre to post following an inpatient CBT intervention for depression (Forsyth et al. 2010). Another study did attempt to measure the relation between dysfunctional attitudes, automatic thoughts, and depression, though only tested structural equation models that had automatic thoughts predicting depression (Kwon and Oei 2003). Additionally, one study found that reductions in ATs and dysfunctional beliefs were significantly associated with decreased depressive symptoms in the course of a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention, naming both as a possible mechanism of action in CBT interventions (Furlong and Oei 2002).

However, there is no research to our knowledge that has empirically examined the temporal nature of the relation of ATs and depressive symptoms. Importantly, no research to our knowledge has examined this temporality in the context of interventions to alleviate depression, which may speak to an important mechanism of CBT and the CBT-AD intervention. Also, previous research on depression and automatic thoughts has been limited in methodology and statistical approaches, often using cross-sectional datasets or statistical approaches that compare data at the same time point, or using techniques that limit statements of temporality. This study aims to determine the temporal relation between ATs and depression, in the context of the CBT-AD treatment, utilizing appropriate methodological and statistical approaches (i.e., cross-lagged panel analysis).

While this is an exploratory study, we hypothesized that, based on previous literature (Kwon and Oei 1992; Moorey 2010) in all three groups, depression and ATs will be positively related, and that ATs will predict depression more so than depression predicts ATs (Kwon and Oei 2003).

Method

Design and procedures

The parent study was a 12-month, 3-arm randomized controlled efficacy trial (Safren et al. 2016). The arms were 1) CBT-AD, 2) ISP-AD and 3) ETAU, as described below. Major assessments were conducted at baseline, 4 months (post-treatment / acute outcome, after all of the intervention sessions ended), 8 months, and 12 months. Visits took place at one of three HIV clinics in New England. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards: Massachusetts General Hospital, Fenway Health, and The Miriam Hospital.

The parent study focused on CBT-AD versus ETAU and ISP-AD for depression and medication adherence in people living with HIV/AIDS (Safren et al., 2016). The parent study found that patients who were assigned to CBT-AD had greater improvements in adherence than did patients who had ETAU after treatment. No significant differences in adherence or depression were noted between CBT-AD and ISP-AD.

Interventions

ETAU

All participants, regardless of treatment assignment, had three enhancements to their usual care: 1) a single-session adherence counseling intervention, Life-Steps (Safren et al. 1999), 2) a provider letter sent after the baseline visit and, 3) at follow-up visits, referrals for depression treatment if clinically indicated.

CBT-AD

In addition to the ETAU content, the 11-session treatment modules, each lasting approximately 50 minutes, included 1) introducing the patient to the nature of CBT and motivational interviewing for behavior change (≈ one session); 2) increasing pleasurable activities and mood monitoring (≈ one session); 3) thought monitoring and cognitive restructuring (i.e., adaptive thinking; ≈ five sessions); 4) problem-solving as a skill to aid in decision-making processes, particularly those related to HIV self-care (≈ two sessions); and 5) relaxation training (≈ two sessions). The therapist and participant were able to, however, structure the number of sessions spent on each module to meet the participants’ individual needs. For all modules, participants were encouraged to apply these skills generally (i.e., via the use of home practice), but they were linked to HIV-care whenever possible. For additional details please see the published treatment manuals (Safren et al. 2007a, 2007b).

ISP-AD

The comparison condition included information with supportive psychotherapy, also in addition to the ETAU content described above. The 11 session ISP-AD manualized intervention developed by our group, with each session lasting up to 60 minutes, included first reviewing the patients’ medication adherence, supportive psychotherapy to build self-esteem and enhance adaptive coping using strategies such as normalization, containment and encouragement. Informational topics also included nutrition, sleep, and depression in the context of HIV, as well as topics related to managing HIV such as an overview of HIV, managing HIV medication side effects, and the impact of risky behaviors, such as drug use, on adherence.

Participants

HIV-positive adults with a clinical diagnosis of depression (N=240) were randomized at a 2:2:1 ratio to three groups (CBT-AD = 94; ISP-AD = 97; ETAU = 49). At baseline, the MINI (Sheehan et al. 1998) was used to assess psychiatric diagnoses. All depression assessments were conducted by a study assessor (Masters or Doctoral-level psychologist, clinical social worker) trained via audio-tape supervision in the assessment protocols. An independent assessor, blinded to treatment condition, conducted the interviewer-administered assessments of depression (Montgomery and Asberg 1979) at the 4-, 8-, and 12-month outcome assessments. Participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and sample characteristics at baseline, all three study arms (N = 240)

| Age M (SD) | 47.4 (8.4) |

|

| |

| Sex n (%) | |

| Male | 165 (68.8) |

| Female | 75 (31.3) |

|

| |

| Race n* | |

| African American/Black | 68 |

| Caucasian/White | 156 |

| Other | 31 |

|

| |

| Hispanic/Latino n (%) | |

| Yes | 26 (10.8) |

| No | 214 (89.2) |

|

| |

| Education n (%) | |

| Partial high school or less | 33 (13.7) |

| High school graduate | 65 (27.1) |

| Partial college | 70 (29.2) |

| College graduate | 72 (30.1) |

|

| |

| Sexual Orientation n (%) | |

| Exclusively homosexual | 81 (33.8) |

| Homosexual with some heterosexual experience | 42 (17.5) |

| Bisexual | 14 (5.8) |

| Heterosexual with some homosexual experience | 18 (7.5) |

| Exclusively heterosexual | 85 (35.4) |

Note.

Participants were able to choose more than one category to indicate their Race.

Measures

Automatic thoughts

The Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ-30; Harrell and Ryon 1983) is a widely used measure with evidence for validity (Harrell and Ryon 1983; Kazdin 1990), and thoroughly examined for reliability, construct validity, sensitivity and specificity (Hill et al. 1989; Ingram et al. 1995). It has also has been used and recommended for use in PLWHA (McIntosh et al. 2013; Pomeroy et al. 2000; Valente 2003). Participants answer items on a 6-point Likert scale. Items assess for automatic thoughts and include statements such as, “I’m worthless,” “I’m so disappointed in myself,” and “I feel so helpless.”

Depression

The interviewer-administered MADRS, a semi-structured clinical interview, (Montgomery and Asberg 1979) has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure in PLWHA (Labbe et al. 2015). The MADRS was used to assess for depressive symptoms at baseline, and months 4, 8, and 12. Ratings were supervised via a selection of audio reviews by a staff psychologist also blind to treatment condition on a weekly basis. All depression assessments were conducted by a study assessor (Masters or Doctoral-level psychologist, clinical social worker) trained via audio-tape supervision in the assessment protocols. The measure assesses for the clinical symptoms of depression, including apparent sadness, reported sadness, reduced sleep, and changes in appetite, using broadly phrased questions about symptoms to more precise ones which allow for a rating of severity.

Data analysis

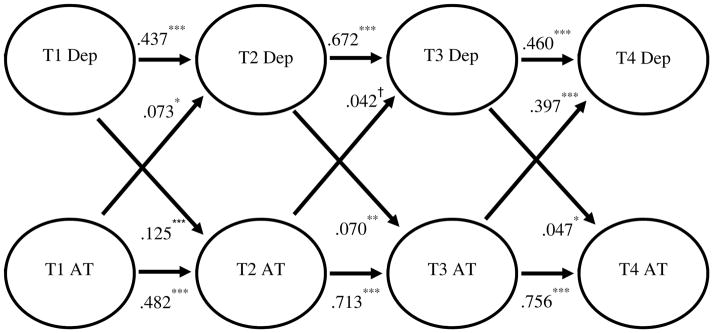

We used a cross-lagged panel analysis to examine temporality and causality between ATs and depression across four time points (see Figure 1), the best technique for determining the nature of the relation between two variables (Berrington et al. 2006). Cross-lagged structural equation models address questions of causal ordering with longitudinal data. An advantage of this type of model is that it is estimated in one step, rather than a series of separate regressions, yielding a global likelihood model and all the tests and indices of model fit that are standard. AMOS version 22 was used to test the cross-lagged panel models.

Figure 1. Conceptual cross-lagged panel analysis model for all three study arms: hypothesized paths between depression (Dep) and automatic thoughts (AT).

Note. Bolded black pathways indicate hypothesized significant relationships, and dashed gray pathways indicate hypothesized non-significant relationships.

Additionally, to further investigate this model across conditions, we ran autoregressive cross-lagged panel models for the CBT-AD and ISP groups separately. Unfortunately, sample size was insufficient to examine ETAU (Preacher and Coffman 2006) due to the 2:2:1 randomization into CBT-AD, ISP, and ETAU groups, respectively. 2:2:1 randomization was used to limit cost, patient burden, and yielded sufficient power to compare the experimental condition (CBT-AD) to the two control groups in the larger parent study.

Power

Using a well-supported tool, R, for establishing power, we calculated necessary sample size to power our analyses at .80 with significance set to .05 (Preacher & Coffman 2006; Preacher, 2014). Ns of 94 and 97 for the CBT-AD and ISP-AD groups were determined to be adequate to detect change, though the N of 49 for ETAU did not power the model well enough as a stand-alone model, according to accepted standards for cross-lagged panel analysis (Preacher, 2014).

Results

Descriptives

The ATQ and MADRS both demonstrated normality. Means for both the ATQ (Baseline = 22.77 [10.01], 4m = 19.42 [10.24], 8m = 17.96 [10.33], 12m = 17.69 [10.50]) and the MADRS (Baseline = 46.34 [15.41], 4m = 39.48 [16.28], 8m = 40.02 [16.83], 12m = 39.84 [16.27]) statistically significantly decreased post-treatment over time. The MADRS and ATQ were related in bivariate correlations (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables at baseline across all three study arms (N=240)

| MADRS | ATQ | Age | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS | 1 | .525** | −.134** | .064 |

| ATQ | .525** | 1 | −.180** | −.124* |

| Age | −.134** | −.180** | 1 | .064 |

| Gender | .064 | −.124* | .064 | 1 |

Note. MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; ATQ = Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) are presented.

. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

These analyses did not include control variables as covariates; control variables decrease variance, limit power, and are not conceptually related to the questions asked. However, to address potential concerns that potential control (demographic) variables may be related to the outcome variables, we ran a series of regression analyses looking at age (age mean = 47.4, age SD = 8.4, age min = 22; age max = 66; B = −.054, p = .428) and automatic thoughts (B = .171, p = .014) and their interaction (B = .102, p = .322) predicting depression, and conversely, age ( B = −.103, p = .065) and depression ( B = .581, p < .001) and their interaction ( B = −.098, p = .053) predicting automatic thoughts, and there was not a significant interaction in these analyses.

Missing data

There were 23 instances of missing data. According to missing value analysis in SPSS, these values appeared to be missing at random. This missing data was accounted for by REML in AMOS.

Cross-lagged panel analysis

The model including all three groups demonstrated that decreases in ATs were followed by decreases in depression (β=.113, p=.048; β=.122, p=.044; β=.172, p=.003), but decreases in depression were not followed by decreases in ATs (β=.097, p=.123; β=−.011, p=.817; β=−.036, p=.427; See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overall cross-lagged panel analysis model with estimates across all three study arms, describing depression (Dep) and automatic thoughts (AT; N =240).

Note. Bolded black pathways indicate observed significant relationships, and dashed gray pathways indicate observed non-significant relationships

Standardized betas (β) are presented.

†Statistical trend; 05 ≤ p ≤ .1

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

In the CBT-AD group, decreases in ATs predicted decreases in depression (β=.073, p=.019; β=.713, p=.085; β=.397, p=<.001), and decreases in depression predicted decreases in ATs (β=.125, p=<.001; β =.070, p=.002; β=.047, p=.026; See Figure 3).

Figure 3. CBT-AD cross-lagged panel analysis model with estimates for CBT-AD arm only, describing depression (Dep) and automatic thoughts (AT; N=94).

Note. Bolded black pathways indicate observed significant relationships, and dashed gray pathways indicate observed non-significant relationships.

Standardized betas (β) are presented.

†Statistical trend; 05 ≤ p ≤ .1

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

However, in the ISP group, while depression and ATs both significantly influenced each other, not all relations were in the direction expected. In the ISP group, ATs demonstrated a positive relation with depression between baseline to month 4 and month 4 to month 8 (β=.202, p<.001; β=.109, p<.001), but not month 8 to month 12 (β=−.116, p = .891. Additionally, there were negative relations between depression predicting ATs at month 4 to month 8 and month 8 to month 12 (β=−.046, p=.049; β=−.039, p=.043; See Figure 4). The relation between depression to ATs at baseline to month 4 was not statistically significant (β=.002, p=.945).

Figure 4. ISP-AD cross-lagged panel analysis model with estimates for ISP-AD arm only, describing depression (Dep) and automatic thoughts (AT; N=97).

Note. Bolded black pathways indicate observed significant relationships, and dashed gray pathways indicate observed non-significant relationships

Standardized betas (β) are presented.

†Statistical trend; 05 ≤ p ≤ .1

** p < .01

*** p < .001

Discussion

These findings explicate the temporal nature of the relation between ATs and depression in PLWHA and depression, which has previously not been explored. The temporal effect on depression from decreases in ATs provides evidence for cognitive interventions to decrease depression in PLWHA. These findings also contribute to explaining the mechanisms through which cognitive behavioral therapies, such as CBT-AD, might work towards decreasing depression in a way that may provide long term benefits, a gap in the literature that has been identified in previous research (Forsyth et al. 2010; Furlong and Oei 2002).

The overall model including all three groups showed that decreases in ATs were followed by decreases in depression, but decreases in depression were not followed by decreases in ATs. This model may be representative of a natural pattern among PLWHA in which ATs act on depression, though depression does not increase ATs. This pattern may suggest that, among PLWHA with depression, it continues to be a valid approach to focus our interventions on decreasing ATs. However, this model must be interpreted with caution, in light of the different patterns of relationships between the groups. More research is needed.

The pattern changes, however, when examining only individuals in the CBT-AD intervention, such that decreases in ATs were followed by decreases in depression, and decreases in depression were followed by decreases in ATs. Since CBT-AD works in part by specifically addressing ATs (Forsyth et al. 2010; Moorey 2010), it may be possible that this change in pattern from the general relation to the CBT-AD only group is related to the fact that CBT-AD specifically addresses ATs. This may in turn create a sort of positive feedback loop, such that in those who receive CBT-AD, as ATs decrease, depression decreases (as in the overall group), but also as depression decreases, ATs decrease as well because CBT-AD has linked depression and ATs for the patients, and a goal of CBT-AD for depression is to break this perpetuating cycle (Moorey 2010). Because ATs and depression are linked together through psychoeducation for the CBT-AD group, a comparatively powerful symptom reduction loop is created, such that decreases in ATs lead to decreased depression, and decreases in depression lead to decreased ATs.

However, since ISP-AD does not directly address ATs, the temporal relation between changes in depression and changes in ATs is not as straightforward. In the ISP-AD group, while depression and ATs both significantly influenced each other, not all relations were in the direction expected, and some relations were not statistically significant. Specifically, decreases in depression predicted increases in ATs between 4 months to 8 months and 8 months to 12 months, and there were no statistically significant relations between baseline depression to month 4 ATs or month 4 ATs and month 8 depressive symptoms. Therefore, in the ISP-AD intervention, despite supportive psychotherapy for depression, ATs may be either remaining or increasing, and as a result, “leaving behind” a cognitive vulnerability factor. If true, the CBT-AD intervention that specifically focuses on ATs may be superior in the longer term.

There are several limitations to note. All of the sites were medical centers in the Northeast, with predominantly male participants, limiting generalizability. Treatments were also delivered under the supervision of PhD-level therapists with extensive knowledge of the intervention. This may limit the exportability of the treatment. It is possible that participants responded differently to the ATQ because they were specifically taught about ATs during the CBT-AD group. Additionally, it is important to note that the model of all participants that include all three study arms is confounded by the presence of a treatment intervention in two out of three groups, and therefore may not be representative of the general population’s pattern of temporality between ATs and depressive symptoms.

Future research should focus on replicability. Additional measurement points may be helpful in further discriminating time-based effects and specificity of these models. Also, empirically testing as to whether this pattern of decreasing ATs and depressive symptoms are, in turn, related to other important outcomes in PLWHA, such as adherence, might be informative. Additionally, to more clearly identify the mechanism by which the CBT-AD intervention is working, a components analyses study would be useful. Also, collecting data from a larger treatment as usual sample could compare the intervention groups to a more naturally occurring pattern of relations between ATs and depressive symptoms in PLWHA. The interaction between age and depression may be important in terms of its relation to outcome automatic thoughts, although not powered to do so in the present study, this interaction may be important to measure and test in a larger sample.

These findings contribute to explaining the mechanism by which cognitive behavioral therapies, or CBT-AD in particular, might work towards decreasing depression in a way that may provide long term benefits. More research into ATs and depression decreasing each other following a CBT-AD intervention would be helpful. Overall, CBT-AD appears to be preferable to ISP and ETAU for people with depression living with HIV/AIDS in that it allows a loop to begin whereby ATs decrease depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms decrease ATs.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project came from a National Institute of Mental Health grant R01MH084757 and a National Institute of Drug Abuse grant K24DA040489 to Dr. Steven A. Safren.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Related Potential Conflicts of Interest Dr. Kristen E. Riley and Jasper S. Lee have no conflicts of interest. Dr. Steven A. Safren receives royalties from Oxford University Press for books/treatment manuals on treating depression in the context of chronic illness.

Human and Animal Rights Statement All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Asch SM, Kilbourne AM, Gifford AL, Burnam MA, Turner B, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA. Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV. Journal of general internal medicine. 2003;18(6):450–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JH, Grant I. Natural history of neuropsychiatric manifestations of HIV disease. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;17(1):17–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrington A, Smith P, Sturgis P. [Accessed 11 August 2016];An overview of methods for the analysis of panel data. 2006 http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/415.

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric Disorders and Drug Use Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Kennard BD, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL, Whiteley LB, Bethel J, et al. Effective Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Medical Clinics for Adolescents and Young Adults Living with HIV: A Controlled Trial. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;71(1) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-Analysis of the Relation Between HIV Infection and Risk for Depressive Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew MA, Becker JT, Sanchez J, Caldararo R, Lopez OL, Wess J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of depressive, anxiety and substance use disorders in HIV-infected and uninfected men: a longitudinal evaluation. Psychological medicine. 1997;27(2):395–409. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance With Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth DM, Poppe K, Nash V, Alarcon RD, Kung S. Measuring Changes in Negative and Positive Thinking in Patients With Depression: Measuring Changes in Negative and Positive Thinking in Patients With Depression. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2010;46(4):257–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong M, Oei TPS. Changes to Automatic Thoughts and Dysfunctional Attitudes in Group CBT for Depression. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;30(3):351–360. doi: 10.1017/S1352465802003107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS Treatment Nonadherence: A Review and Meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011:1. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Depression and Diabetes Treatment Nonadherence: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2398–2403. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell TH, Ryon NB. Cognitive-behavioral assessment of depression: clinical validation of the automatic thoughts questionnaire. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1983;51(5):721. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CV, Oei TPS, Hill MA. An empirical investigation of the specificity and sensitivity of the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire and Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1989;11(4):291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Kendall PC. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive therapy and research. 1980;4(4):383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LB, Towner WJ, Klein DB, Bersoff-Matcha S, et al. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(3):384–390. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d53e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Kendall PC, Siegle G, Guarino J, McLaughlin SC. Psychometric properties of the Positive Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):495. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, Laurenceau JP, Balbin E, Klimas N, et al. Psychosocial Factors Predict CD4 and Viral Load Change in Men and Women With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(6):1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evaluation of the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire: Negative cognitive processes and depression among children. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;2(1):73. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Amirkhanian YA. The newest epidemic: a review of HIV/AIDS in Central and Eastern Europe. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2003;14(6):361–371. doi: 10.1258/095646203765371231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SM, Oei TP. Differential causal roles of dysfunctional attitudes and automatic thoughts in depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992;16(3):309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SM, Oei TPS. Cognitive change processes in a group cognitive behavior therapy of depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2003;34(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe AK, O’Cleirigh CM, Stein M, Safren SA. Depression CBT treatment gains among HIV-infected persons with a history of injection drug use varies as a function of baseline substance use. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2015;20(7):870–877. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.999809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(5):539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh RC, Seay JS, Antoni MH, Schneiderman N. Cognitive vulnerability for depression in HIV. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;150(3):908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British journal of psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorey S. The Six Cycles Maintenance Model: Growing a “Vicious Flower” for Depression. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38(2):173–184. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Newcomb ME, Mayer KH, Skeer M, Traeger L, Safren SA. Moderate Levels of Depression Predict Sexual Transmission Risk in HIV-Infected MSM: A Longitudinal Analysis of Data From Six Sites Involved in a “Prevention for Positives” Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(5):1764–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA. A review of treatment studies of depression in HIV. Topics in HIV medicine. 2006;14(3):112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Miller WC, Whetten K, Eron JJ, Gaynes BN. Prevalence of DSM-IV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the Southeastern United States. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42(3):298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219773.82055.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy EC, Kiam R, Green DL. Reducing depression, anxiety, and trauma of male inmates: An HIV/AIDS psychoeducational group intervention. Social Work Research. 2000;24(3):156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Coffman DL. Computing power and minimum sample size for RMSEA [Computer software] 2006 http://quantpsy.org/

- Safren SA, Bedoya CA, O’Cleirigh C, Biello KB, Pinkston MM, Stein MD, et al. Treating Depression and Adherence (CBT-AD) in Patients with HIV in Care: A Three-arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Lancet HIV. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30053-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Soroudi N. Coping with chronic illness: Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression, client workbook. NY: Oxford University Press; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Soroudi N. Coping with chronic illness: Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression, therapist guide. NY: Oxford University Press; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, Psaros C, Delahanty LM, Blashill AJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(3):625–633. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(3):404–415. doi: 10.1037/a0028208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, Mayer KH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1999;6(4):332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Sternberg M, Beardslee WR. Associations of Depression, Self-Esteem, and Substance Use with Sexual Risk among Adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(3):179–189. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Safren SA, Manhart LE, Lyda K, Grossman CI, Rao D, et al. Challenges in Addressing Depression in HIV Research: Assessment, Cultural Context, and Methods. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(2):376–388. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9836-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Wiebe JS, Sauceda JA, Huh D, Sanchez G, Longoria V, et al. A Preliminary RCT of CBT-AD for Adherence and Depression Among HIV-Positive Latinos on the U.S.-Mexico Border: The Nuevo Día Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(8):2816–2829. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Alloy LB. A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(2):116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM. The Effect of Mental Illness, Substance Use, and Treatment for Depression on the Initiation of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Individuals. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(3):233–243. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Low-, Middle- and High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2014;11(3):291–307. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente SM. Depression and HIV Disease. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS care. 2003;14(2):41–51. doi: 10.1177/1055329002250993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]