Abstract

Participation in romantic relationships during adolescence and young adulthood provides opportunities to explore one’s sexuality, yet may also cause distress once these relationships dissolve. Although researchers have asserted that participation in same-sex relationships may be beneficial for young gay and bisexual men’s (YGBM) psychosocial well-being, less is known about YGBM appraisals of breakups after participating in same-sex relationships. We examined the association between self-reported psychological well-being (e.g., symptoms of depression and anxiety; self-esteem, sense of personal competency) and YGBM’s negative and positive appraisals of breakups within a sample of single YGBM (N=1,040; ages 18–24) who reported prior serious same-sex relationships. Negative appraisals were associated with lower psychological well-being. Positive appraisals were associated with greater anxiety symptoms, self-esteem and sense of personal competency. Our findings highlight the need to acknowledge how YGBM’s differential responses to breakups may be associated with their psychological well-being.

Keywords: Dating, Love, Mental Health, Appraisals, Coping, Youth

Dating is an integral part of adolescence and young adulthood, and is distinct from other forms of relationships that may be experienced during childhood (Davila, Steinberg, Kachadourian, Cobb, & Fincham, 2004; Greca & Harrison, 2005). Dating can be broadly defined as practices whereby individuals explore intimacy, emotions, and sexual desires with another person or persons (Greca & Harrison, 2005). Dating involves a range of emotional and time commitments and can be conceptualized as ranging from a single event (e.g., first date, hookup, or casual encounter) to a dynamic relationship over time (e.g., long-term relationship, open relationship). The exploration of romantic and sexual feelings through dating is an essential element of identity formation, as these relationships allow youth to develop and refine relationship scripts that may be used throughout the life course (Furman & Shaffer, 2003; Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000). Yet, compared to the volume of research that has focused on heterosexual youth’s relationships, less is known about the relationship experiences, attitudes, and outcomes for sexual minority youth (i.e., youth who do not identify as heterosexual in terms of identity, desires, or behaviors) (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009). Prior research among sexual minority couples has utilized several relationship theories, including attachment theory (Cook and Calebs, 2016), interdependence theory (Darbes, Chakravarty, Neilands, Beougher & Hoff, 2014), and the investment model (Kurdek & Schmitt, 1986), to examine the context and predictors of relationship quality and dissolution, but no single theory has emerged as dominant. Nor has there been much attention to the impact of relationship dissolution on mental health outcomes. Regardless of theoretical approach, the investigation of relational experiences and appraisals is particularly important as intimate relationships offer resources that are crucial for optimal mental health (Collins et al., 2009; Iida, Seidman, Shrout, Fujita, & Bolger, 2008).

Compared to their heterosexual peers, YGBM’s involvement in romantic relationships may be stalled in adolescence due to the development of a non-heterosexual identity (Bauermeister, Johns, Sandfort, Eisenberg, Grossman, & D’Augelli, 2010), and stress associated with internalized homophobia and fear of rejection from family and friends (Diamond, Savin-Williams, & Dubé, 1999; Starks, Newcomb & Mustanski, 2015). These stressors can lead to increases in mental health symptoms and to deter the development of a healthy self-concept (Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2015). Within this context, participation in same-sex relationships may be particularly important in the lives of young gay and bisexual men. For example, participation in same-sex relationships (SSRs) has been postulated as a promotive factor for sexual minority youth’s psychological well-being (Detrie & Lease, 2007), as researchers have noted that participation in SSRs may reduce psychological distress over time (Bauermeister et al., 2010; Russell & Consolacion, 2003). These findings parallel studies with heterosexual youth, where participation in romantic relationships have been found to be associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression symptoms (Davila, et al., 2004; Greca, & Harrison, 2005). Taken together, these studies suggest that participation in relationships may be beneficial to the psychological well-being of youth. Therefore, we ask, if being in a relationship is beneficial for youth, is the dissolution of relationship, or breaking-up, necessarily harmful?

Many romantic relationships during youth development are temporary, with youth being likely to experience multiple relationships in a relatively short amount of time (Eyre, Milbrath, & Peacock, 2007; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Clerkin, 2011). However, few studies have examined how breakups experienced in a relatively short amount of time may be linked to youth’s well-being. Researchers have argued that breakups can have negative psychosocial consequences (such as lowered self-esteem, changed relational- or self-image, or even vengeful or spiteful thinking) for youth that relate to their mental health, identity formation, and further development of dating scripts (Adam, 2006; Eyre et al., 2007). For example, researchers have found that men involved in different-sex relationships (DSRs) that ended in a breakup at their partner’s request experience a significant level of psychosocial distress (Helgeson, 1994; Simon & Barrett, 2010). In a study among predominately heterosexual sample of youth, negatively-valenced breakup appraisals (e.g., the feeling that they lost something sacred to them) were associated with greater anger and distress after the breakup (Hawley, Mahoney, Pargament, & Gordon, 2015). These researchers hypothesize that breakups are associated with negative rumination, decreased levels of social support and self-esteem, and other negative mental health outcomes (Cupach, Spitzberg, Bolingbroke, & Tellitocci, 2011; Helgeson, 1994; Simon & Barrett, 2010). Although one could hypothesize that YGBM likely experience similar distress as their peers in DSRs, the available literature examining the consequences of breakups among young me in SSRs is limited and merits further attention in the literature.

Although breakups are often portrayed as stressful life events, their impact on the well-being of individuals may depend on how this stressor is appraised. Consistent with Stress & Coping Theory, opportunities to find meaning in a stressful event may yield health promotive results (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Folkman, 1997). This, in-part, depends on how one appraises their events—as either positive or negative. Positive cognitive appraisals of an event or process are reflections and subsequent affirmations that an individual has of an event as beneficial, rewarding, or promotive of the individual’s well-being, life, or specific situation. On the other-hand, negative cognitive appraisals of an event or process are reflections and affirmations in which the individual deems the event harmful and damaging to their self (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988; Folkman, 1997). Research on stress-related or post-traumatic growth, for example, suggests that having positively-valenced cognitive apprisals of the event are an important component for people to experience growth, rather than distress and despair (Park, Cohen, & Murch, 1996), and to report better physical and mental health outcomes (Barskova & Oesterreich, 2009; Herrenkohl, Kosterman, Hawkins, & Mason, 2009; Milam, Ritt-Olson, & Unger, 2004; Park, Cohen, & Murch, 1996; Park & Fenster, 2004; Wang, Rendina, & Pachankis, 2016). For example, Tashiro and Frazier (2003) asked college students who participated in DSRs how they felt after a breakup, in terms of growth and distress. They found that breakups can hold the potential to help a young person grow and develop a better sense of what they desire in future relationships, depending on the person’s causal attributions for the breakup, or their personal levels of agreeableness. In another study, researchers found that adults who appraised that a breakup aligned with their relationship desires, such as wanting independence or self-directedness, were more likely to feel more positive emotions and fewer negative emotions after the breakup (McCarthy, Lambert, & Brack, 1997). Beyond dating, studies based in divorce literature also suggest that leaving an unhealthy relationship can be promotive of better mental health (Amato, 2010). At present, however, little is known about YGBM’s appraisals of breakups and their consequences for psychological well-being. This is particularly problematic as prior developmental research has cautioned against assuming that the social and psychological contexts of SSR are analogous to DSR (Diamond, Savin-Williams, & Dubé, 1999).

YGBM experience SSR in a heteronormative context, in which the social norm is DSR and SSR are less common. Compared to heterosexual peers, for example, YGBM have a more restricted pool of potential dating partners during adolescence and emerging adulthood, which might influence how they react to relationship breakups (Diamond, Savin-Williams, & Dubé, 1999). In light of the mental health disparities experienced by sexual minority young men (Haas et al., 2011; Russell & Fish, 2016), examining how breakup-related appraisals are associated with YGBM’s psychological well-being may inform the design of positive youth development interventions to help YGBM positively re-appraise the dissolution of their relationships, as these cognitions could serve as scripts that not only guide future behavior, but also positively impact their mental health (Simon, Kobielski, & Martin, 2008; Tashiro & Frazier, 2003).

At present, however, we do not know what YGBM’s appraisals regarding breakups are, or the appraisals’ implications for YGBM’s psychological well-being. Because youth may experience multiple relationships and breakups in a short time, which may create compounded feelings and emotions across these recent relationship experiences, it is difficult to ascribe breakup-related appraisals for each breakup experience. Therefore, we examine youth’s general appraisals of breakups, and associations with psychological well-being, as these appraisals may persist after the breakup and shape how new relationships are perceived in the future. Building on the prior research in this area, our study examines how positive versus negative appraisals of breakups are associated with the psychological wellbeing of YGBM who reported at least one serious same-sex relationship in their lifetime. Consistent with previous literature, we hypothesized that that higher endorsement of negative breakup appraisals would be associated with poorer mental health outcomes, whereas higher endorsement of positive breakup appraisals would be associated with positive mental health outcomes among YGBM.

Methods

Sample

Data for this paper come from a cross-sectional observational study examining YGBM’s sexual and psychological well-being. To be eligible for participation, recruits had to self-identify as male, report having same-sex attractions (regardless of how they self-identified their sexual orientation), be between the ages of 18 to 24 (inclusive), report being single, speak English, and be a resident of the United States (including Puerto Rico). Participants were primarily recruited through advertisements on two popular social networking sites and participant referrals. One social networking site was primarily marketed as a dating and hooking-up space, whereas the other social networking site was broader and could be used to post comments, share pictures, and chat with friends. Social network advertisements were viewable only to men who fit our age range and who lived in the United States. Promotional materials displayed a synopsis of eligibility criteria, a mention of a $10 VISA e-card incentive, and the survey’s website.

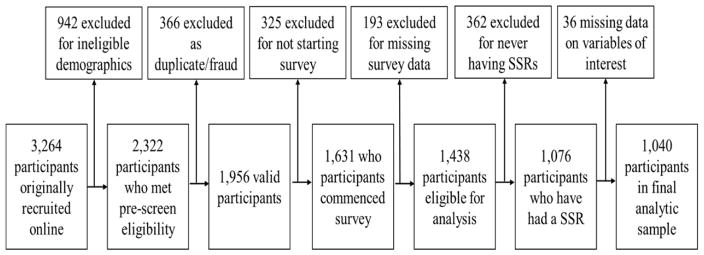

The process for selecting our final analytic sample from our original pool of participants is detailed in Figure A. A total of 3,264 entries were recorded over the 7 months of data collection (July 2012–January 2013). We excluded 942 entries because they did not meet eligibility requirements. We then identified duplicates and falsified entries by manually examining participants’ online presence, email and IP addresses, operating system and browser information, irregular answer patterns, and time taken to complete survey (Bauermeister et al., 2012), and subsequently disqualified another 366 entries because they were identified as duplicate/fraudulent entries, leaving us with a total of 1,956 valid entries. Of these, 325 participants consented but did not commence the survey (i.e., missing all data; 16.6 %); and another 193 consented participants did not complete all sections of the survey (i.e., missing data in some sections of the survey; 10.5%), and were excluded from analysis. Therefore, we were left with a sample of N = 1,438 eligible YMSM.

Figure A.

Participant recruitment and exclusion strategy. This figure illustrates how we determined our final analytic sample, starting from the original sample of recruited YGBM.

For the purposes of defining our analytic sample, we excluded participants who had never had a relationship from our analyses (n=362), as they differed substantially from their counterparts who had had at least one same-sex relationship lasting at least 3 months in their lifetime (n=1,076). The excluded participants were significantly younger (Mage = 20.40, SDage = 1.83) than those with at least one SSR (M = 20.99, SD = 1.92; t = 5.10, p ≤ 0.001). Excluded participants were significantly older (M = 16.25, SD = 2.58) when they first came out to at least one person compared to participants with at least on SSR (M = 15.60, SD = 2.51; t = 4.28, p ≤ 0.001). Excluded participants were also significantly less likely to have had a sexual experience with a same-sex partner (64.09% sexually active) than participants who had participated in a SSR (77.89% sexually active; χ2 = 59.81, p ≤ 0.001). There were no significant differences in racial or ethnic identity, level of education or sexual identity between the sample of interest and excluded participants. Excluded participants reported a lower mean score of positive appraisal endorsement (M = 3.42, SD = 1.10) than those who had one or more SSR in their lifetime (M = 3.63, SD = 1.09; t = 3.08, p ≤ 0.01). Excluded participants reported a lower mean score of negative appraisal endorsement (M = 2.76, SD = 1.16) than those who had one or more SSR in their life time (M = 2.91, SD = 1.17; t = 2.23, p ≤ 0.05). Finally, excluded participants reported a lower mean score of anxiety symptoms (M = 2.83, SD = 0.62) than those who had one or more SSR in their life time (M = 2.90, SD = 0.57; t = 2.06, p ≤ 0.05). We observed no significant differences in mean depressive symptoms or self-esteem scores. Once these excluded participants were removed, our analytic sample was N = 1,076. As a final step, we excluded 36 participants as they were missing data on one or more of the variables under study (see Attrition Analyses in the Results section).

Procedures

We developed our web survey using best practices (Couper, 2008), including various iterations of pilot testing prior to data collection. Study data were protected with a 128-bit SSL encryption and kept within a firewalled server. Upon entering the study site, participants were asked to enter a valid and private email address to serve as their username. This allowed participants to save their answers and, if unable to complete the questionnaire in one sitting, continue the questionnaire at a later time. Upon completing an eligibility screener, eligible youth were presented with a detailed consent form that explained the purpose of the study and their rights as participants, and were asked to acknowledge that they had read and understood each section of the consent form. Consented participants answered a 30–45 minute online questionnaire that covered assessments regarding their socio-demographic characteristics, Internet use, ideal relationship and partner characteristics, sexual behaviors, and psychological well-being. For those questionnaires that were incomplete, participants were sent two reminder emails that encouraged them to complete the questionnaire. We acquired a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health to protect study data. Our Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

Mental Health Outcomes

To assess participants’ overall mental health, we assessed their levels of several different mental health outcomes, including depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, self-esteem, and sense of personal competency.

For depressive symptoms, participants answered the 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Participants rated 10 statements (Kohout, Berkman, Evans, & Cornoni-Huntley, 1993) using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = Rarely or none to 4 = All of the time, indicating how often they felt a statement applied to them in the past week. Examples of statements were “I felt depressed”, “I felt lonely”, as well as some reverse-scored items such as “I was happy,” and “I felt hopeful about the future.” We then computed a mean composite score, where higher scores indicate greater levels of depressive symptoms (Cronbach α = .85).

For anxiety symptoms, participants completed the 6-item anxiety symptoms subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1975) using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Never to 4 = Very Often, indicating how often they felt a statement applied to them in the past week. Examples of statements were “Feeling fearful”, “Spells of terror or panic”, and “Feeling so restless you couldn’t sit still.” We then computed a mean composite score, where higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety (Cronbach α = .92).

Participants’ self-esteem was assessed with the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants answered each statement using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree, indicating the degree as to how much each statement matched their own self-perceptions. Examples of statements were “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”, “I am able to do things as well as most other people”, as well as some reverse-scored items such as “At times I think I am no good at all,” and “I feel I do not have much to be proud of.” We then computed a mean composite score, where higher scores indicate greater levels of self-esteem (Cronbach α = .88).

Participants’ personal competency was self-rated using 14 statements reflecting personal competence and control from the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Participants used a 4-point scale rated from 1 = Never True to 4 = Often True, indicating the degree of how much each statement applied to themselves in the past month. Examples of statements were “No matter what challenge I face, I always find a solution,” “I can handle unpleasant feelings,” and “I have realistic plans for the future.” We then computed a mean composite score, where higher scores indicated greater levels of perceived personal competency (Cronbach α = .93).

Breakup Appraisals

In our review, we were not able to find a validated scale that assessed sexual minority youth’s assessment of breakup-related appraisals. Therefore, we developed six items focused on participants’ views on breakups. We used Principal Axis Factoring with Varimax Rotation to extract two factors: Factor 1 (Negative Appraisal; Eigenvalue=2.47) accounted for 41.09% of the total variance and Factor 2 (Positive Appraisal; Eigenvalue=1.51) accounted for an additional 25.13% of the total variance (see Table 2 for factor loadings).

Table 2.

Rotated squared loadings for components of factor analysis for Positive and Negative Appraisal scales.

| Component | Factor 1: Negative Appraisals | Factor 2: Positive Appraisals |

|---|---|---|

| I feel powerless when a partner breaks up with me | .87 | −.04 |

| My self-esteem goes down when a partner breaks up with me. | .82 | −.04 |

| Breakups tend to affect my day-to-day activities negatively. | .82 | −.00 |

| I tend to blame myself for my breakups. | .61 | .01 |

| When a relationship ends, I ultimately leave with a better sense of what I can offer in a future relationship. | −.01 | .87 |

| When a relationship ends, I ultimately leave with a better sense of what I desire in a future relationship. | −.02 | .86 |

|

| ||

| Variance explained | 41.09% | 25.13% |

| Cronbach’s α | .86 | .86 |

The Negative Appraisal Scale was rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Not True to 5 = Very True. The Negative Appraisal Scale includes four items: “I tend to blame myself for my breakups,” “My self-esteem goes down when a partner breaks up with me,” “I feel powerless when a partner breaks up with me,” and “Breakups tend to affect my day-to-day activities negatively.” We then computed a mean composite score, where higher scores indicate greater endorsement of negative appraisals (Cronbach α = .86).

To measure positive appraisals, participants rated statements using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Not True to 5 = Very True. The Positive Appraisal Scale includes two items: “When a relationship ends, I ultimately leave with a better sense of what I desire in a future relationship,” and “When a relationship ends, I ultimately leave with a better sense of what I can offer in a future relationship.” We computed a mean composite score, where higher scores indicate greater endorsement of positive appraisals (Cronbach α = .86).

Same-sex Relationships (SSR)

We used the SSR descriptive measures reported by Bauermeister et al. (2010) to assess participants’ relationship history, we examined the number of SSRs in a participant’s lifetime, their age when they had their first SSR, and their first same-sex partner’s age. We computed the difference in age between participants and their first same-sex partner by subtracting participants’ response to the item “How old was this person when you first became involved?” from their response to “How old were you when you had your first serious relationship (lasting more than 3 months) with a man?”. We also examined the number of SSRs that participants had in the past year.

Demographic characteristics

Respondents reported their age (in years). Respondents were asked to report if they considered themselves of Latino or Hispanic ethnicity, followed by the following racial categories: African American or Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, White or European American, Native American, and Other. We combined the Native American and Other race categories given the limited number of observations, and created dummy variables for each race/ethnicity group. White non-Latino participants served as the referent group in our analyses. Participants were asked to self-report their sexual identity (“How do you self-identify?”) and asked to check all the responses that applied: Gay/homosexual; Bisexual; Straight/heterosexual; Same-gender loving; Man who has sex with men; 6 = Other (participants in the other category self-identified as queer, fluid, polyamorous, pansexual, demisexual, and asexual). A subsequent question asked them to indicate the identity that most closely fit with how they self-identify. Given that the majority of participants self-identified as gay, we created a dichotomous variable for sexual identity, where non-gay participants served as the referent group. Participants also reported the age, in years, when they first came out to someone, and whether or not they had ever been sexually active (engaging in anal intercourse) with a same-sex partner.

Data Analytic Strategy

Prior to conducting our multivariate analyses, we compared participants who had not reported ever having a relationship (n = 362) to those who had (n = 1,076). We then conducted descriptive statistics for our analytic sample (N = 1,040; Table 1). To look at differences across our variables of interest, we separated our sample into participants who had no SSRs in the past year, and participants who had one or more SSRs in the past year. Using chi-squares and t-test analyses, we then compared categorical and continuous descriptive variables for participants who had no serious relationships within the past year to those who had at least one serious relationship in the past year (Table 1). We also examined the bivariate associations between continuous variables in a correlation matrix (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic variables, relationships across a lifetime, breakup appraisals, and mental health for participants who have had 0 relationships (n = 431) versus 1 or more relationships (n = 609) in the past year (N = 1,040).

| 0 relationships M(SD)/N(%) |

1+ relationships M(SD)/N(%) |

Total M(SD)/N(%) |

|t/χ2| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21.30(1.88) | 20.81(1.93) | 21.02(1.92) | 4.09*** |

| Race | 3.24 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 285(27.4%) | 401(38.6%) | 686(66.0%) | |

| Latino | 73(7.0%) | 121(11.7%) | 194(18.7%) | |

| Black/African American | 37(3.6%) | 45(4.3%) | 82(7.9%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 14(1.3%) | 17(1.6%) | 31(3.0%) | |

| Multi-Racial | 14(1.3%) | 19(1.8%) | 33(3.2%) | |

| Other Race | 8(0.8%) | 6(0.6%) | 14(1.3%) | |

| Education | 3.55 | |||

| No High School | 18(1.7%) | 20(1.9%) | 38(3.7%) | |

| High School Diploma | 78(7.5%) | 128(12.3%) | 206(19.8%) | |

| Technical/Associate | 23(2.2%) | 42(4.0%) | 65(6.3%) | |

| Some College | 209(20.1%) | 290(27.9%) | 499(48.0%) | |

| College | 72(6.9%) | 92(8.8%) | 164(15.8%) | |

| Some Graduate School | 31(3.0%) | 37(3.6%) | 68(6.5%) | |

| Sexual Identity | 2.28 | |||

| Gay Identified | 408(39.2%) | 562(54.0%) | 970(93.3%) | |

| Non-Gay Identified | 23(2.2%) | 47(4.5%) | 70(6.7%) | |

| Frist “Out” Age | 15.20(2.27) | 15.89(2.62) | 15.60(2.50) | 4.44*** |

| Sexually Active | 428(41.2%) | 604(58.1%) | 1032(99.2%) | .05 |

| Relationships (lifetime) | ||||

| Number | 1.90(1.29) | 2.52(1.87) | 2.26(1.68) | 6.36*** |

| Age of First Relationship | 17.31(2.30) | 17.75(2.90) | 17.57(2.68) | 2.60** |

| Difference in age of first partner | 1.85(4.06) | 2.08(4.40) | 1.98(4.26) | .83 |

| Breakup Appraisals | ||||

| Positive Appraisals | 3.57(1.07) | 3.68(1.10) | 3.63(1.09) | 1.63 |

| Negative Appraisals | 2.92(1.15) | 2.90(1.20) | 2.91(1.18) | .25 |

| Mental Health | ||||

| Depression | 2.16(.64) | 2.16(.64) | 2.16(.64) | .20 |

| Anxiety | 2.14(.98) | 2.18(1.06) | 2.16(1.03) | .62 |

| Self-esteem | 2.88(.58) | 2.91(.56) | 2.89(.57) | .85 |

| Personal Competency | 3.29(.54) | 3.33(.54) | 3.31(.54) | 1.07 |

Note.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix of Study Variables (N=1,040)

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | .42*** | −.04 | −.09** | −.09** | −.09** | .12*** | .04 |

| 2. Education | 1.0 | .04 | −.05 | −.08* | −.05 | .13*** | .12*** |

| 3. Positive Appraisals | 1.0 | −.08* | −.07* | .03 | .20*** | .30*** | |

| 4. Negative Appraisals | 1.0 | .49*** | .39*** | −.47*** | −.25*** | ||

| 5. Depression | 1.0 | .71*** | −.61*** | −.41*** | |||

| 6. Anxiety | 1.0 | −.48*** | −.25*** | ||||

| 7. Self-Esteem | 1.0 | .63*** | |||||

| 8. Personal Competency | 1.0 |

Note.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

To test our hypotheses, we ran multivariate linear regression analyses (Table 4) among number of past year relationships (none, one, or two or more), and our two different breakup appraisal scales, after accounting for socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, education, sexual orientation). Using no past year relationships as the referent, we included two indicators for number of past relationships (e.g., 1 relationship vs. 2+ relationships) in order to examine whether participants who had multiple recent breakups reported different psychological well-being outcomes than those who only had one recent breakup. We ran a regression model for each one of our mental health outcomes. For brevity, only statistically-significant findings (p<.05) are presented below.

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regressions on mental health outcomes for men who have had at least one serious same-sex relationship in their lifetime (N = 1,040).

| Depression | Anxiety | Self-Esteem | Personal Competency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b(SE) | β | b(SE) | β | b(SE) | β | b(SE) | β | |

| Age | −.01(.01) | −.04 | −.03(.02) | −.06 | .02(.01)* | .07 | −.00(.01) | −.01 |

| Gay | −.10(.07) | −.04 | −.39(.12)** | −.09 | .15(.06)* | .06 | .11(.06) | .05 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black | −.01(.07) | −.01 | .04(.11) | .01 | −.03(.06) | −.01 | −.02(.06) | −.01 |

| Asian/PI | −.11(.10) | −.03 | −.03(.17) | −.01 | −.01(.09) | .00 | .13(.09) | .04 |

| Latino | .08(.04) | .05 | .20(.08)** | .07 | −.03(.04) | −.02 | −.01(.04) | −.01 |

| Other Race | −.03(.15) | −.01 | .20(.25) | .02 | .36(.13)** | .07 | .35(.13)** | .08 |

| Education | −.01(.02) | −.03 | .01(.03) | .01 | .03(.01)* | .06 | .04(.01)** | .09 |

| Relationships (past year) | ||||||||

| 1 | −.02(.04) | −.01 | −.05(.06) | −.02 | .03(.03) | .03 | .02(.03) | .02 |

| 2+ | .07(.06) | .04 | .22(.09)* | .07 | .05(.05) | .03 | .06(.05) | .04 |

| Negative Appraisal | .26(.01) *** | .48 | .34(.02)*** | .39 | −.21(.01)*** | −.44 | −.10(.01)*** | −.23 |

| Positive Appraisal | −.02(.02) | −.03 | .06(.03)* | .06 | .09(.01)*** | .16 | .14(.01)*** | .27 |

| Constant | 1.85(.23)*** | 1.89(.38)*** | 2.52(.20)*** | 2.87(.20)*** | ||||

Notes.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

For the Personal Competency regression analysis, 10 participants were excluded due to missing data (N=1,030). Non-gay identified participants serve as referent group for sexual identity. Non-Hispanic Whites serve as referent group for race/ethnicity. Participants who did not report a serious SSR in the prior year serve as referent group.

Results

Attrition Analyses

In preparation for our multivariate analyses, we removed any participants who had missing data in our variables of interest (n = 36). Participants with missing data (Mage = 20.17, SDage = 1.73) were significantly younger than the analyzed sample (Mage = 21.02, SDage = 1.92; t = 2.62, p ≤ 0.01). There were no significant differences in racial and ethnic identity, in level of education, in the number of participants who identified as gay, in the age participants first came out, or in whether or not they had engaged in sexual activity with a same-sex partner. On average, participants with missing data reported being a younger age during their first relationship (Mage = 15.78, SDage = 2.61) than the analyzed sample (Mage = 16.53, SDage = 2.15; t = 2.05, p ≤ 0.05). There were no significant differences in the mean number of serious relationships or the mean difference in age between a participant and his first serious romantic partner. Finally, there were no significant differences between the samples among our breakup appraisal variables, or mental health variables.

Sample Description

Descriptive statistics for our sample (N = 1,040) are provided in Table 1. On average, participants had more than one relationship in their lifetime, first coming out at an average age between 15 and 16 years old, with their first serious partner being about two-years older than themselves. Most participants (58.6 %) had at least one relationship in the past year, and the vast majority (99.2%) of them were sexually active. In order to examine whether those who had a more recent breakup (e.g., past year) differed from those who had a breakup more than a year ago, we separated our sample into two groups—those who had zero relationships in the past year (n = 431, 41.4%), and those who had one or more relationships in the past year (n = 609, 58.6%). Those who had no SSRs in the past year were significantly older than those who did report having a SSR in the past year, and were significantly younger when they first came out compared to those who did have a SSR in the past year. Participants who did not have a SSR in the past year reported fewer lifetime relationships on average, and were slightly younger at their age of their first relationship (Table 1). We observed no other difference among participants based on their number of SSRs in the past year. Overall, participants reported higher mean scores in the positive appraisals regarding breakups (M = 3.63, SD = 1.09) than they did for negative appraisals (M = 2.91, SD = 1.18).

Psychological Outcomes

Depressive Symptoms

Our regression model [F (11, 1039) = 32.01, p ≤ .001] indicated that higher depressive symptom scores were associated with higher endorsement of negative appraisals (Table 4). We did not find an association between depressive symptoms and endorsement of positive appraisals, the number of past relationships, or the socio-demographic characteristics. The adjusted R2 for this model was 24.7%.

Anxiety Symptoms

Our regression analysis for anxiety symptoms [F (11, 1039) = 21.06, p ≤ .001] indicated that higher anxiety symptoms were associated with higher endorsement of both negative and positive appraisals, respectively. Furthermore, compared to not having had a relationship in the prior year, we found that participants who had two or more relationships in the past year reported higher anxiety symptoms. We found no mean difference in anxiety symptoms between those who had one SSR in the prior year as compared to those who had no SSR. Participants who self-identified as gay reported fewer anxiety symptoms than non-gay counterparts. Latinos were more likely than White counterparts to report higher anxiety scores. We found no other differences in our anxiety model. The adjusted R2 for this model was 17.5%.

Self-Esteem

Our regression analysis for self-esteem [F (11, 1039) = 34.25, p ≤ .001] indicated that self-esteem scores were negatively associated with negative appraisals, and positively associated with positive appraisals (Table 4). Self-esteem was positively associated with participants who were older in age, had higher educational attainment, and who self-identified as gay. Compared to White counterparts, participants who reported Other Race/Ethnicity reported higher mean self-esteem scores; no other differences across race/ethnicity were observed. No other variables were associated with self-esteem. The adjusted R2 for this model was 26.0%.

Personal Competency

Our regression analysis of personal competency [F (11, 1029) = 47.60, p ≤ 0.001] indicated that personal competency scores were negatively associated with negative appraisals, and positively associated with positive appraisals (Table 4). Personal competency was also positively associated with identifying with an “other” racial identity, and with having a higher educational attainment. No other variables were associated with personal competency. The adjusted R2 for this model was 15.1%.

Discussion

Researchers have suggested that breakups are a cause of significant psychological distress among heterosexual youth (Cupach et al., 2011; Helgeson, 1994; Simon & Barrett, 2010), and may influence their dating scripts based on their endorsement of negative and positive appraisals (Simon et al., 2008). At present, however, there is limited research investigating YGBM’s breakup appraisals and associations with psychological well-being. Consistent with prior literature with heterosexual youth, negative appraisals were associated with poorer mental health outcomes among this sample of YGBM (Cupach et al., 2011; Helgeson, 1994; Simon & Barrett, 2010; Simon et al., 2008; Tashiro & Frazier, 2003). Although the association between mental health and negative appraisals may be attributable to negatively valenced relational scripts (Simon et al., 2008), it is possible that endorsement of negative appraisals may promote negative rumination and hinder individuals’ ability to deal with stress. Cognitive introspection is necessary for processing an experience and subsequently developing an individual’s scripts and appraisals of the event (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004); however, researchers have found that intrusive and negative rumination is not related to growth, but rather to distress (Nolen-Hoeksema, McBride, & Larson, 1997; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). Negative rumination, or brooding, has been associated with a higher likelihood of developing depressive and anxiety symptoms (Armey et al., 2009), and lower self-esteem (Kross, Ayduk, & Mischel, 2005). Future research examining how YGBM cognitively manage negatively-appraised stressors, as well as how it influences relational scripts over time, is warranted.

Positively valenced break-up related appraisals were associated with positive mental health outcomes among YGBM, a finding supported by the prior literature with heterosexual youth. Tashiro & Frazier (2003), for example, found that youth who held positive feelings regarding a breakup were more likely to develop a better sense of what they wanted in future relationships. Interestingly, greater endorsement of positive break-up related appraisals was also associated with greater symptoms of anxiety. Parallel to our negative appraisal findings, this result could be an indication of rumination. Given the absence of an association between positive appraisals and depressive symptoms, however, we interpret this relationship to be indicative of potential emotional growth and not necessarily psychopathology. As mentioned above, this is concurrent with theory that proposes some level of cognitive introspection on an event is necessary for growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2006; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). According to Treynor, Gonzalez, and Nolen-Hoeksema (2003), as well as Armey and colleagues (2009), rumination manifests itself in two different forms—reflection and brooding. Contrary to brooding, reflection is a more neutral form of rumination that is less intense and used to assess stressful situations. In addition, research regarding post-traumatic and stress-related growth has empirically demonstrated that deliberate, event-related rumination is promotive of positive appraisals and subsequent growth (Calhoun, Cann, & Tedeschi, 2000). Thus, it is possible that YGBM endorsing positive breakup-related appraisals are engaging in reflective rumination about their breakup—spending a significant amount of time and cognition trying to rationalize events—and experiencing some anxiety as a result. In addition, we found that young men who had more than one recent breakup in the prior year reported greater anxiety symptoms. Future work should investigate whether rumination styles (e.g., reflective vs. brooding), alongside the number of recent breakups, influence the association between YGBM’s mental health outcomes and their endorsement of negative and positive appraisals, respectively, as it may inform coping-based interventions for this population.

Taken together, our findings provide novel insight into the experiences of YGBM’s relationships and its associations to mental health. Nevertheless, our findings raise new questions that merit exploration. To further differentiate between breakup appraisals and rumination, future research should assess not only the endorsement of appraisals, but also the frequency of the appraisals as thoughts—as frequency of thoughts is an indicator of rumination (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). Furthermore, our study lays further groundwork for longitudinal studies to examine breakup appraisals, rumination, and mental health. It is possible that while youth’s breakups are still relatively recent, they may be endorsing different styles of appraisals at different time points, and thus may be experiencing different mental health outcomes. Moreover, whether or not the young adult in question initiated the breakup could have different implications for their appraisals and mental health outcomes. Finally, other coping skills could impact the degree to which appraisals influence YGBM’s mental health, and even whether or not they have the ability for differing levels of reflective appraisal. Future research that characterizes YGBM’s dating and breakup experiences over time and examines its association to coping and mental health is warranted.

There are several additional limitations meriting mention. First, our sample may not be generalizable to all YGBM. Given the absence of a population frame from which to recruit a random sample of YGBM, we employed a convenience sampling method. Participants were recruited online, which could mean that our analyses may not include the experiences of YGBM who do not have access to the Internet. However, given our desire to confidentially engage YGBM in multiple regions across the country, in a manner where they could conduct this survey in privacy and reduce the likelihood of them responding untruthfully due to social desirability bias, we believe that this was the best method for participant recruitment for a study of this scale. Further limiting generalizability is our exclusion criteria limiting our sample only to YGBM who have engaged in anal intercourse, as not all youth engage in anal intercourse, and some end up never engaging in anal intercourse (Bruce, Harper, Fernández, & Jamil, 2012). However, given that condomless anal intercourse puts YGBM at a higher-risk for HIV infection than other sexual activities, we sought to study this population living with potentially increased risk. Second, our study is cross-sectional by design; therefore, no causal relationships should be made from our findings. In addition, further investigation should be conducted to refine and validate our quantitative assessment of breakup appraisals. Future research employing a mixed-methods approach may help us examine the experiences and sentiments behind youth’s reasoning for endorsing certain attitudes, and their relationship with rumination, script development, and mental health. Third, our data collection was subject to potential recall bias, as participants were asked to retrospectively reflect on past relationships. Fourth, although participants’ data were de-identified, and they were told so during consenting, because participants still provided an email address for verification and incentivizing purposes, they may have felt that their data could be tracked, and thus did not answer truthfully, subjecting our data to potential social desirability bias. Furthermore, having to provide an email address could have discouraged some YGBM from participating, due to the same concern, or due to lack of an email address. Finally, we were not able to assess specific characteristics about the quality of our participants’ relationships—we only know that if they indicated participating in an SSR, that the participant was committed to a partner for at least 3 months. Moreover, while we know when the participant came out, we were not able to assess whether they had shared with their friends and family that they were in a SSR. In future studies refining the implications of breakup appraisal assessment on relational and mental health, these variables will be important to consider.

Despite these limitations, this study provides novel insight into a perspective on YGBM’s breakup appraisals. As our research suggests, endorsement of either positive or negative appraisals seem to be related to YGBM’s mental health. Mental health practitioners may want to discuss their clients’ relationship desires and beliefs, as well as explore their breakup experiences, when appropriate. As youth are likely to experiment with dating and breakups frequently (Eyre et al., 2007; Mustanski et al., 2011), helping youth to foster more positive appraisals—or at the very least, avoiding development of negative appraisals—rather than focus on avoiding breakups or frequent dating, may promote better mental health outcomes post-breakups. For example, this could be facilitated by coping skills training tailored for experiencing a break-up. Similar work had demonstrated clinical effectiveness among youth in Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT). In this relatively-brief, low-intensity series of psychotherapy sessions aimed at alleviating symptoms of acute depression, therapists guide their patients in not only recognizing their depressive symptomology, but also reflecting and improving upon their social functioning (Weissman & Klerman, 1990). Given the rapid emotional development of adolescents, and quick turn-over in different relationships for many, IPT has had great success in helping adolescents and youth deal with depressive symptoms related to their interpersonal relationships (Weisz, McCarthy, Valeri, 2006). The need for such clinical support for youth at risk of mental health symptomology who are also experiencing breakups is especially important, given research suggesting that youth experiencing depressive symptoms in a relationship are more likely to perceive that they are unsupported—specifically during relational conflict—and thus experience poorer relational health (Gordon, Tuskeviciute, & Chen, 2013). Finally, we hope that our findings regarding breakup appraisals encourage practitioners to be more sensitive to the idea that different stages of relationships may promote different mental health outcomes, as well as to the idea that differing perspectives on relationships have different implications for mental health. We encourage further investigation into the mechanisms behind the associations between breakup appraisals, same-sex participation, and mental health, as solidifying our knowledge in the specific causal pathways of these associations could open new and rewarding venues for mental and sexual health practitioners to discuss these topics when working with sexual minority young men.

Acknowledgments

Data for this study come from a Career Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01-MH087242; PI: Bauermeister). Dr. Bauermeister was supported by a R34 grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (R34MH101997-01A1). Views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agency.

Contributor Information

Peter Ceglarek, University of Michigan.

Lynae Darbes, University of Michigan.

Rob Stephenson, University of Michigan.

Jose Bauermeister, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Adam BD. Relationship innovation in male couples. Sexualities. 2006;9(1):5–26. http://doi.org/10.1177/1363460706060685. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):650–666. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.l741-3737.2010.007. [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, Fresco DM, Moore MT, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG, … Alloy LB. Brooding and pondering: Isolating the active ingredients of depressive rumination with exploratory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Assessment. 2009;16(4):315–327. doi: 10.1177/1073191109340388. http://doi.org/10.1177/1073191109340388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barskova T, Oesterreich R. Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009;31(21):1709–1733. doi: 10.1080/09638280902738441. http://doi.org/10.1080/09638280902738441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Sandfort TGM, Eisenberg A, Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1148–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Pingel E, Zimmerman M, Couper M, Carballo-Dieguez A, Strecher VJ. Data quality in HIV/AIDS web-based surveys: Handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods. 2012;24(3):272–291. doi: 10.1177/1525822X12443097. http://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X12443097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Harper GW, Fernández MI, Jamil OB. Age-concordant and age-discordant sexual behavior among gay and bisexual male adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(2):441–448. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9730-8. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9730-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun LG, Cann A, Tedeschi RG. A correlational test of the relationship between posttraumatic Ggowth, religion, and cognitive processing. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13(3):521– 527. doi: 10.1023/A:1007745627077. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007745627077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Furman W, Konarski R. The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71(5):1395–408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00235. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. http://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SH, Calebs BJ. The integrated attachment and sexual minority stress model: Understanding the role of adult attachment in the health and well-being of sexual minority men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;42(3):164–173. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2016.1165173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper MP. Designing Effective Web Surveys. New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cupach WR, Spitzberg BH, Bolingbroke CM, Tellitocci BS. Persistence of attempts to reconcile a terminated romantic relationship: A partial test of relational goal pursuit theory. Communication Reports. 2011;24(2):99–115. http://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2011.613737. [Google Scholar]

- Darbes LA, Chakravarty D, Neilands TB, Beougher SC, Hoff CC. Sexual risk for HIV among gay male couples: a longitudinal study of the impact of relationship dynamics. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):47–60. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0206-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Steinberg SJ, Kachadourian L, Cobb R, Fincham F. Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: The role of a preoccupied relational style. Personal Relationships. 2004;11(2):161–178. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00076.x. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. The Affects Balance Scale. Baltimore, M.D: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Detrie PM, Lease SH. The relation of social support, connectedness, and collective self-esteem to the psychological well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 2007;53(4):173–199. doi: 10.1080/00918360802103449. http://doi.org/10.1080/00918360802103449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L, Savin-Williams RC, Dubé EM. Sex, dating, passionate friendships, and romance: Intimate peer relations among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. In: Furman W, Bradford Brown B, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre SL, Milbrath C, Peacock B. Romantic relationships trajectories of African American gay/bisexual adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;22(2):107–131. http://doi.org/10.1177/0895904805298417. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science Medecine. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science and Medicine. 1988;26(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. http://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent Romantic Relations and Sexual Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practical Implications. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Tuskeviciute R, Chen S. A multimethod investigation of depressive symptoms, perceived understanding, and relationship quality. Personal Relationships. 2013;20(4):635–654. http://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12005. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, … Clayton PJ. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality. 2011;58(1):10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. http://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley AR, Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Gordon AK. Sexuality and spirituality as predictors of distress over a romantic breakup: Mediated and moderated pathways. Spirituality in Clinical Practice. 2015;2(2):145–159. http://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000034. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS. Long-distance romantic relationships: Sex differences in adjustment and breakup. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20(3):254–265. http://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294203003. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Mason WA. Effects of growth in family conflict in adolescence on adult depressive symptoms: Mediating and moderating effects of stress and school bonding. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida M, Seidman G, Shrout PE, Fujita K, Bolger N. Modeling support provision in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94(3):460–478. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.460. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D Depression Symptoms Index. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. http://doi.org/10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Ayduk O, Mischel W. When asking “why” does not hurt: Distinguishing rumination from reflective processing of negative emotions. Psychological Science. 2005;16(9):709–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01600.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA, Schmitt JP. Relationship quality of partners in heterosexual married, heterosexual cohabiting, and gay and lesbian relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(4):711–720. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CJ, Lambert RG, Brack G. Structural model of coping, appraisals, and emotions after relationship breakup. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1997;76(1):53–64. http://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1997.tb02376.x. [Google Scholar]

- Milam JE, Ritt-Olson A, Unger JB. Posttraumatic growth among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(2):192–204. http://doi.org/10.1177/0743558403258273. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Newcomb ME, Clerkin E. Relationship characteristics and sexual risk-taking in young men who have sex with men. Health Psychology. 2011;30(5):597–605. doi: 10.1037/a0023858. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0023858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, McBride A, Larson J. Rumination and psychological distress among bereaved partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(4):855–862. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.855. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Cohen LH, Murch RL. Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality. 1996;64(March 1996):71–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Fenster JR. Stress-related growth: predictors of occurrence and correlates with psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23(2):195–215. http://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.2.195.31019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-image. Princenton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Russell S, Consolacion T. Adolescent romance and emotional health in the United States: Beyond binaries. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):499–508. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_2. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016;12:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. http://doi.org/:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Cohen KM. Developmental trajectories and milestones of lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people. International Review of Psychiatry. 2015;27(5):357–366. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1093465. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1093465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Barrett AE. Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(2):168–182. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. http://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon V, Kobielski S, Martin S. Conflict beliefs, goals, and behavior in romantic relationships during late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(3):324–335. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9264-5. [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. A longitudinal study of interpersonal relationships among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents and young adults: Mediational pathways from attachment to romantic relationship quality. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44(7):1821–1831. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0492-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro T, Frazier P. “I’ll never be in a relationship like that again”: Personal growth following romantic relationship breakups. Personal Relationships. 2003;10(1):113–128. http://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.00039. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LC. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15(1):1–18. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma & Transformation: Growing in the Aftermath of Suffering. Thousand Oaks, C.A: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: An expanded framework. In: Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG, editors. Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):247–259. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Rendina HJ, Pachankis JE. Looking on the bright side of stigma: How stress-related growth facilitates adaptive coping among gay and bisexual men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2016;0(0):1–13. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2016.1175396. http://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2016.1175396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression. In: Wolberg B, Stricker G, editors. Depressive Disorders. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1990. pp. 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCarthy CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]