Abstract

Contextual and intrapersonal factors affecting the development of African American men’s romantic relationship commitment-related behavior were investigated. Socioeconomic disadvantage during early adolescence was hypothesized to predict harsh, unsupportive parenting practices. Harsh parenting was hypothesized to result in youths’ emotion-regulation difficulties, indicated by elevated levels of anger during mid-adolescence, particularly when men were exposed to racial discrimination. Young African American men’s anger during mid-adolescence, a consequence of harsh, unsupportive parenting and racial discrimination, was expected to predict commitment-related behavior. Hypotheses were tested with a sample of rural African American men participating in a panel study from the ages of 11 through 21. Data from teachers, parents, and youths were integrated into a multi-reporter measurement plan. Results confirmed the hypothesized associations. Study findings indicate that the combination of harsh parenting and racial discrimination is a powerful antecedent of young men’s commitment-related behavior. Anger across mid-adolescence mediated this interaction effect.

Keywords: adolescence, youth/emergent adulthood, intimacy, African Americans, commitment, parent, adolescent relations

Both theory and empirical research have focused on the ways in which emerging adult romantic relationships unfold over time. By late adolescence and emerging adulthood, many relationships become steady, exclusive, and characterized by high levels of intimacy and commitment; such relationships establish the foundation for future family formation (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009; Karney, Beckett, Collins, & Shaw, 2007). Studies investigating sexual health among young African American men have revealed important challenges to their development of exclusive, intimate relationships. During adolescence and emerging adulthood, disproportionate rates of multiple sexual partnerships characterize African American men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Often, men’s reports of multiple partnerships indicate a sexual concurrency pattern in which sexual relationships with different women overlap, although one woman is considered the primary, steady partner (Senn, Carey, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2009). Multiple and concurrent sexual partnerships have important implications for men’s and their partners’ sexual health because such partnerships are related to elevated levels of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancies (Adimora, Schoenbach, Martinson, Donaldson, Fullilove, & Aral, 2001). In addition to sexual health-related concerns, engagement in multiple partnerships, rather than serially monogamous relationships, may have prognostic implications for young men’s psychosocial development and their formation of families as adults (Karney et al., 2007).

Research also documents the challenges that many African American men experience during later adulthood in developing and maintaining stable, satisfying romantic relationships (Amato, 2011). Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, romantic relationships among African Americans in general, and emerging adults in particular, are characterized by considerable conflict, instability, and dissatisfaction (Amato, 2011; Kurdek, 2008). African Americans’ dramatically declining marriage rates since the mid-1980s provide further evidence of the disproportionate relationship challenges that they experience (Amato, 2011).

Patterns of young men’s sexual partnering in emerging adulthood and studies of African American adults’ relationship quality underscore the importance of investigating African American emerging adult men’s relationship commitment behavior. In the context of romantic relationships, emerging adults’ commitment-related behavior may be characterized by more or less stability, relationship satisfaction, and sexual fidelity (Furman & Rose, 2015; Karney et al., 2007). We acknowledge that, for some emerging adults, relationship commitment may be the exception rather than the rule. Some researchers suggest that it is normative among middle- and upper-class youths for romantic commitment to be delayed due to career preparation and trends toward later family formation (Shulman & Connolly, 2013). This view is consistent with a perception of emerging adulthood as a psychosocial moratorium, a time of exploration and a form of extended adolescence (Arnett, 2000). This view of the emerging adult transition, however, does not apply to socioeconomically disadvantaged minority youths (Arnett & Brody, 2008). For a number of African American men, poor preparation for work and secondary education, a lack of family economic resources, and experience with racial discrimination affect the nature and prognostic significance of emerging adulthood (Arnett & Brody, 2008). In contrast to a period of experimentation, emerging adulthood is more likely to have enduring consequences than to reflect a temporary developmental transition.

The emerging adult transition thus provides an important window for understanding the development of African American men’s romantic relationships. Research to date has documented the role of a range of race-related stressors in undermining close relationships among African Americans in general, and men in particular (Bowman, 2006; Johnson, 2010). These stressors include socioeconomic conditions such as poverty, sociocultural expectations such as race and sex stereotypes, and sociohistorical processes including racial subordination and discrimination (Spencer, 2001). Singly and in combination, these stressors marginalize African American men in families (Bowman, 2006) and compel men to develop coping strategies to deal with harsh environments (Cunningham & Meunier, 2004; Spencer, Cunningham, & Swanson, 1995).

Recent research has focused on how exposure over time to systems of opportunity and constraint in African American youths’ lives affect emerging adult romantic relationships (Kogan, Lei, et al., 2013; L. G. Simons, Simons, Landor, Bryant, & Beach, 2014; R. L. Simons, Simons, Lei, & Landor, 2012). These studies emphasize how challenging socioeconomic circumstances not only undermine relationships at a single time point but also, over time, prompt a range of emotional responses and coping strategies that have the potential to affect men’s engagement in satisfying and committed relationships (Kogan, Lei, et al., 2013; L. G. Simons et al., 2014). For example, socioeconomic circumstances (Brody, Yu, Beach, Kogan, Windle, & Philibert, 2014; R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011; R. L. Simons et al., 2012) and other forms of race-related adversity (Brody, Chen, Kogan, Murry, Logan, & Luo, 2008) affect parent–youth relationships, which provide a foundation for intimacy in future romantic relationships (Furman & Rose, 2015). Investigations that specifically address African American men’s commitment-related behavior, however, have focused primarily on public health issues such as HIV risk and teenage fatherhood. Studies of the developmental processes that shape young men’s commitment-related behavior are rare. This constitutes grounds for concern because considerable evidence reveals sex differences in relationship commitment development and experience (Giordano, Longmore, & Manning, 2006). Thus, studies that combine men and women may miss important, sex-specific information regarding the development of commitment.

Study Hypotheses

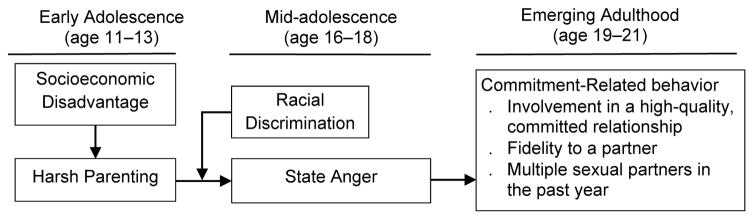

In the present study we investigated developmental factors affecting African American emerging adult men’s commitment-related behavior. Hypotheses were tested with data from young men and their caregivers who lived in resource-poor, rural southern environments. This focus is unique given the ubiquity of studies focusing on African American men in densely populated inner cities. Socioeconomic and race-related disadvantages, however, can have equally detrimental effects in rural and urban contexts (Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, De Marco, & Bratsch-Hines, 2012). We hypothesized that socioeconomic disadvantage in early adolescence (ages 11 through 14) would predict parents’ use of harsh and unsupportive caregiving practices. Exposure to harsh parenting would result in youths’ difficulties with emotion regulation, as indicated by elevated levels of anger across mid-adolescence. We expected harsh parenting to be particularly influential when young men were exposed to racial discrimination. Finally, we hypothesized that young men’s anger during mid-adolescence, a consequence of harsh parenting and racial discrimination, would predict commitment-related behavior (see Figure 1 for a summary of study hypotheses).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of the Pathways Linking Socioeconomic Risk to Commitment-Related Behavior Among African American Males During Emerging Adulthood.

Socioeconomic disadvantage is hypothesized to initiate a cascade of risks that affect the likelihood that young men will form committed, romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Relationship commitment behavior includes men’s demonstrated involvement in high-quality, monogamous relationships as well as their avoidance of involvement with multiple sexual partners (Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Collins et al., 2009). Specific socioeconomic disadvantages include inadequate family resources, parental unemployment, a single-parent family structure, and low parental education. The accumulation of these factors predicts a range of youth outcomes, including internalizing and externalizing behaviors and substance use (Ackerman, Brown, & Izard, 2004; Scaramella, Neppl, Ontai, & Conger, 2008). Resource inadequacy, single-parent status, and low parental education, both individually and in combination, have been linked to African American adolescents’ involvement with multiple sexual partners (Moore & Chase-Lansdale, 2001; Scaramella et al., 2008), romantic relationship quality, and attitudes toward marriage (Simons et al., 2012). Recent studies also revealed that socioeconomic disadvantages in adolescence are linked to romantic relationship quality among African American emerging adults (Kogan, Lei, et al., 2013) and forecast sexual partnering patterns among young men (Kogan, Yu, Brody, & Allen, 2013).

Studies of parenting behavior among African Americans suggest that male youths may receive less monitoring and be subject to less stringent behavioral expectations than are female youths (Cunningham, Mars, & Burns, 2012; Varner & Mandara, 2014). Despite these tendencies, the strains and multiple demands that socioeconomic stressors impose can tax even the most concerned caregivers and induce them to use harsh parenting practices that, by design, quickly terminate aversive child and adolescent behavior (Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd, & Brody, 2002). Parents from impoverished socioeconomic backgrounds and those with little education report less frequent nurturing behaviors and discipline that is more harsh than consistent (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003; Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002). Thus, during preadolescence and early adolescence, harsh, unsupportive parenting induced by socioeconomic stressors can be expected to influence negatively young men’s relationship commitment behavior. Parent–child and parent–adolescent relationship quality is a robust predictor of emerging adults’ behaviors in romantic relationships (Collins et al., 2009). Warmth and sensitivity in family interactions during adolescence predicts nurturing and supportive interactions with romantic partners during adolescence (Furman & Simon, 2004) and early adulthood (Black & Schutte, 2006; Seiffge-Krenke, Overbeek, & Vermulst, 2010). Conversely, youths exposed to harsh parenting report elevated conflict in their romantic relationships (Simons et al., 2014). Combined, these studies suggest that parenting practices during early adolescence may be potent factors in shaping emerging adults’ participation in romantic relationships.

We hypothesized that exposure to harsh, unsupportive parenting practices would affect young men’s commitment-related behavior indirectly through effects on their emotion regulation, particularly as it is enacted through anger and its expression (Davies, Winter, & Cicchetti, 2006; Simons & Burt, 2011). Theoretical (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002) and empirical (Hakulinen et al., 2013; Lemerise & Dodge, 2008) research indicate that growing up in chaotic families that lack warmth is associated with the development of hostility and anger. Youths who receive harsh parenting become, over time, more likely to maintain a heightened state of vigilance for signs of anger and to reciprocate it (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2009; Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994). Chronic anger is associated with scanning the environment for negative cues, low inhibition, and interpersonally unproductive expressions of negative emotions (Berkowitz, 2012). Thus, anger can impair both the formation of a committed relationship and the expression of positive behavior toward a romantic partner. Hostile attribution processes are particularly likely to be expressed as relationships become increasingly intimate (Overall, Girme, Lemay, & Hammond, 2014), affecting both relationship satisfaction and stability (Diamond & Hicks, 2005; Guyll, Cutrona, Burzette, & Russell, 2010).

We hypothesized that racial discrimination would amplify the effect of harsh parenting on adolescent anger. Discrimination, defined as unfair treatment because of minority status by individuals from a dominant group (Williams & Mohammed, 2013), includes racial microstressors, routine demoralizing and dehumanizing experiences with racism that include being ignored, overlooked, or subjected to minor mistreatment based on one’s race. Among African Americans, male youths are more likely than female youths to report racial microstressors (Brody, Kogan, & Chen, 2012). Although major racism-related events such as being denied a bank loan may happen infrequently, microstressors are common and tend to escalate across adolescence (Brody et al., 2006). The routine and pervasive aspects of this treatment appear to take a greater toll on mental health than do major discriminatory events (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Williams & Mohammed, 2013).

Exposure to racial discrimination has well-documented negative outcomes among young people (Sanders-Phillips, Settles-Reaves, Walker, & Brownlow, 2009). Researchers, however, recently have advocated examinations of the ways in which various forms of stress may interact to affect developmental outcomes (Estrada-Martínez et al., 2012; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Racial discrimination as an exacerbating factor for other stressors, such as harsh parenting, is of particular interest. Discrimination’s pervasive and destructive influence on male African American youths in rural contexts has been documented (Brody et al., 2008; Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004), and research indicates the plausibility of its action as a moderator. Specifically, Murry, Brown, Brody, Cutrona, and Simons (2001) studied economic distress and parenting among 383 rural African American families. Their analysis revealed that racial discrimination functioned as a moderator that amplified the negative influence of economic distress on both African American mothers’ psychological adjustment and the influence of psychological distress on their parenting behavior. This supports the likelihood that racial discrimination functions as an amplifier of other stressors. The majority of studies on the interaction between racial discrimination and adolescents’ family relationships, however, have focused on the buffering influence of family relationships (Gibbons et al., 2010; Simons et al., 2006). This focus does not allow for the detection of amplification of negative outcomes in the absence of protective family processes. For example, R. L. Simons et al. (2006) found that supportive parenting interacted with racial discrimination to affect violent behavior among African American male adolescents. For youths with supportive parents, racial discrimination had little or no influence on violence. Yet examination of the interaction graph revealed a crossover: As supportive parenting diminished, the influence of discrimination increased. Thus, studies that examine the effects of negative parenting practices and youths’ exposure to discrimination are needed.

Other research suggests that the confluence of harsh parenting and racial discrimination may have a unique influence on African American male youths. Researchers have identified a willingness to express anger as a component of a hypermasculine coping style used by some African American youths exposed to dangerous community environments (Cassidy & Stevenson, 2005; Cunningham, Swanson, & Hayes, 2013). Readiness to express anger and to engage in hostile attribution processes also figure prominently in Anderson’s (1999) work on the “code of the street” in which hostility is thought to play a major role in avoiding victimization within the community. Exposure to racial discrimination and other adversity in childhood are linked both to street code adherence (R. L. Simons et al., 2012) and to generally cynical viewpoints associated with hostile behavior in relationships (R. L. Simons et al., 2012). Thus, exposure to a combination of harsh parenting and racial discrimination has the potential to promote both high levels of anger as an immediate emotional response to demeaning treatment and the development of a negative behavioral style as an adaptation to a harsh environment.

The Current Study

Patterns of men’s sexual partnering in emerging adulthood and studies of African American adults’ relationship quality underscore the importance of investigating the development of African American men’s commitment-related behavior, particularly among those from socioeconomically disadvantaged environments. We tested hypotheses regarding the development of commitment-related behavior during emerging adulthood. Socioconomic disadvantages are hypothesized to increase young men’s exposure to harsh parenting in early adolescence, which carries forward throughout adolescence by affecting feelings of anger. We further hypothesized that exposure to racial discrmination in mid-adolescence would exacerbate the anger-inducing influence of harsh parenting. Because antecedent internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood influence both parent–adolescent relationships and youths’ development of problems with anger, the influence of such symptoms at age 11 was controlled in the analyses. Hypotheses were tested with a sample of rural African American men who took part in a panel study from the ages of 11 through 21. Data from teachers, parents, and youths were integrated into a multireporter measurement plan.

Method

Study hypotheses were tested with data from 315 African American male youths, their primary caregivers, and their fifth-grade teachers, who were participating in a panel study. Families were recruited randomly from public school lists in seven rural Georgia counties when the youths were in the fifth grade. These communities were representative of a region in the rural South characterized by persistent poverty among African Americans (Wimberly & Morris, 1997). Study participants in one half of the communities received a family-centered preventive intervention. Because intervention efficacy is not a focus of our hypotheses, intervention assignment and dosage were controlled in analyses of study hypotheses.

At baseline, participants’ mean household gross monthly income was $2,095 (SD = $1,422) and mean monthly per capita gross income was $525 (SD = $416). Although 73.8% of the primary caregivers were employed outside the home and worked an average of 39.9 hours per week, 44.7% of the families lived below federal poverty standards and another 23.4% lived within 150% of the poverty threshold; they could be described as working poor. Single mothers headed a majority (58.7%) of the families. The primary caregivers’ modal level of education was a high school diploma or GED (52.9%). Participants’ demographic characteristics were similar to those of the Georgia communities from which they were sampled (Boatright, 2009).

Nine waves of data were collected from participants (see Table 1). Most constructs presented in Figure 1 were operationalized using multi-wave measures within three developmental time points: (a) early adolescence, (b) mid-adolescence, and (c) emerging adulthood. This strategy allows for enhanced reliability in the evaluation of constructs across each time point. Attrition from Wave 1 through Wave 6 was 18.7%. Participants retained through Wave 6 did not differ on any study variables from those who left the project. At Wave 7, we intentionally followed up with only 227 of the participants due to funding constraints. From Wave 7 through Wave 9, attrition was 11.1%. Participants retained at Wave 9 did not differ on any study variables from those who left the project.

Table 1.

Sample Waves, Attrition, and Measurement Time-Points

| Stage | Wave | M age (SD) | Sample (n) | Constructs Assessed at Each Wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Adolescence | 1 | 11.6 (0.35) | 315 | Socioeconomic disadvantage/Family and parenting |

| 2 | 12.3 (0.32) | 304 | ||

| 3 | 13.2 (0.32) | 296 | ||

|

| ||||

| Mid-adolescence | 4 | 16.0 (0.37) | 250 | Racial discrimination/Anger |

|

|

||||

| 5 | 17.0 (0.50) | 244 | Anger | |

|

|

||||

| 6 | 18.4 (0.47) | 256 | Anger | |

|

| ||||

| Emerging Adulthood | 7 | 19.2 (0.64)* | 227 | Multiple partners in past 3 months/High-quality romantic relationship/Infidelity to a partner |

| 8 | 20.0 (0.67) | 216 | ||

| 9 | 21.1 (0.70) | 204 | ||

Sample size reduced due to budgetary constraints.

Procedure

Trained African American field researchers conducted computer-based interviews in participants’ homes at each of the nine waves of data collection. Youths and primary caregivers were interviewed individually and privately and were told that their answers were strictly confidential and would not be disclosed to anyone within or outside the family. For Waves 1 through 6, participants were read questions and entered their answers via a remote keypad. For Waves 7 through 9, interviews were conducted with computer-assisted self-interviews with audio enhancements. In this method, participants wore headphones through which items were read and then they recorded their responses on the computer. Parents received $75 and youths received $25 for each interview at Waves 1 through 5. For Waves 7 through 9, emerging adults received $50 for their participation. The university institutional review board approved all project protocols.

Measures

Socioeconomic disadvantage

Socioeconomic disadvantage was assessed with an index validated in previous research by our team (Brody et al., 2013). The index is based on six variables: (a) single-parent family status, (b) low parental education level, (c) family poverty, (d) caregiver unemployment, (e) family receipt of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and (f) perceived inadequate income. Families received a score of 1 or 0 to indicate the presence or absence of each risk factor; the sum of risk factors comprised the index. This strategy is consistent with the observation that socioeconomic and contextual risks tend to function in an additive manner on the basis of the number of risks experienced, rather than the extensiveness of particular risk factors (Sameroff & Fiese, 2000). Caregivers self-reported their family structure: 0 (more than 1 parent) or 1 (single parent); level of education: 0 (high school diploma or more) or 1 (less than a high school diploma); employment status (full time, part time, unemployed); and receipt of TANF (yes/no) and income from all sources on a demographic questionnaire. Poverty status was calculated with per capita figures for the year in which the data were collected. A single item was used to assess the primary caregiver’s perceptions of the adequacy of the family’s income in meeting their needs. The response scale included: 1 (much less than adequate), 2 (not adequate), 3 (adequate), 4 (more than adequate), and 5 (much more than adequate). A score of 1 was assigned to the ratings much less than adequate and not adequate; a score of 0 was assigned to all other responses. The summed risk index ranged from 0 through 6 for each wave of assessment and was summed across three waves, with a mean of 6.61 (SD = 3.89).

Harsh, unsupportive parenting

Harsh parenting was operationalized as a multi-reporter, latent construct indicated using three scales. Parents and youths completed the four-item Harsh Parenting Scale (Brody et al., 2001) to assess caregivers’ use of slapping, hitting, and shouting to discipline the youths. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .54 to .66 across the assessments at ages 11, 12, and 13. Low internal consistency is common in the literature for measures of harsh parenting due to low base rates of these disciplinary practices (Brody et al., 2001; R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011). Use, or lack thereof, of supportive and nurturing behavior was assessed with a five-item nurturant-involved parenting scale (R. L. Simons et al., 2006). Example items included, “How often does your child talk to you about things that bother him/her?” and “How often do you ask your teen what he/she thinks before making decisions that affect him/her?” Cronbach’s alphas for this scale ranged, across reporters and waves, from .76 to .82. Parents and youths also reported on relationship harmony and distress using the Interaction Behavior Questionnaire (Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary, 1979; e.g., “Your child is easy to get along with”); alphas exceeded .90 at Waves 1 through 3. Within-reporter correlations across time exceeded .30 for youths and .42 for parents. Repeated measures across time were first averaged within reporters. Parent and youth reports were significantly intercorrelated at each time point and subsequently averaged. Reliability for each measure across reporters and time exceeded .80. The resulting multi-reporter, multi-time-point indices of (a) harsh parenting, (b) nurturant parenting, and (c) relationship harmony were used as indicators of a latent harsh, unsupportive parenting construct.

Anger

At Waves 4 through 6, youths’ anger was measured using the 15-item State Anger Scale (Spielberger, 1999). Youths were asked how often they experienced discrete emotions (e.g., “I am furious” or “I feel angry”) on a scale ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never). Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .91 to .92 across the three waves.

Commitment behavior

Commitment-related behavior was assessed at youth ages 19, 20, and 21 years (see Table 1). Young people reported on the numbers of sexual partners they had during the past 3 months (“In the past 3 months, how many people have you had sex with?”) Those who reported two or more sexual partners in the past 3 months were coded “1,” and those with no sexual partners or one sexual partner in the past 3 months were coded “0.” The study summed the three time points to form an index of multiple partnerships. At each emerging adulthood wave, we coded youths as being in high-quality romantic relationships (1) or not (0). This was determined by using the following information. Youths were asked if they were currently in a committed relationship lasting 4 weeks or longer. Youths who were in relationships reported on the quality of those relationships using the 12-item Network Relationship Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). The items measured and assessed (a) partner emotional support (e.g., “How often do you depend on your partners for help, advice, or sympathy?”), (b) partner instrumental support (e.g., “How often does your partner help you figure out or fix things?”), (c) support toward partner (e.g., “How often do you help your partner with things that she can’t do by herself?”), and (d) relationship security (e.g., “How sure are you that this relationship will last no matter what?”). Items were rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (very often/very sure). Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .88 to .90 across waves. Youths also reported conflict with romantic partners on the Ineffective Arguing Inventory (Kurdek, 1994). They rated, on a scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly), statements about the conflicts they had with their romantic partners. Example items included, “You and your partner’s arguments are left hanging and unsettled,” and “You and your partner go for days being mad at each other.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .70 to .78 across the three waves. Romantic relationship support and conflict scores were standardized, and the conflict scores were subtracted from the support scores to form the romantic relationship quality scores. In each wave, youths with positive relationship quality scores (more support, less conflict) were coded “1,” and those with negative relationship quality scores (more conflict, less support) were coded “0.” Infidelity was assessed for youths reporting a current relationship or one in the past year. In each case, youths responded to the question, “Have you had sex with another person while dating this partner?” Youths who responded yes were assigned a code of “1,” and those who responded no were assigned a code of “0.” The codes were summed across the three waves to indicate the number of years in which infidelities were reported. In summary, the commitment-related behavior construct is composed of three indices, each ranging from 0 through 3: (a) multiple sexual partnerships (M = 0.94; SD = 0.98), (b) high-quality committed relationships (M = 0.86; SD = 0.85), and (c) infidelity in a committed relationship (M = 0.42; SD = 0.71).

Racial discrimination

At Wave 4, the youths self-reported their experiences of racial discrimination with a scale adapted from the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). Items from the original scale were presented to rural African American community members, who identified the most common forms of racial microstressors and suggested wording changes (Brody et al., 2006). Participants also suggested reducing the number of points in the Likert response scale. Youths reported how often in the past 12 months each of nine microstressors occurred, from 1 (never) to 4 (frequently). Example items included, “How often have you been treated rudely or disrespectfully because of your race?” and “How often have your ideas or opinions been put down, ignored, or belittled because of your race?” Cronbach’s alpha was .87.

Control variable

The youths’ homeroom teachers reported Wave 1 behavior problems on the Teacher’s Report Form (Achenbach, 1991). Teachers completed items pertaining to withdrawn, aggressive, and rule-breaking behavior. Cronbach’s alpha was .81.

Data Analysis

The conceptual model in Figure 1 was tested with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), as implemented in Mplus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007). Models were estimated using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator, which tests hypotheses against all available data from Waves 1 through 9. Thus, missing data did not result in deleted cases. The previously described attrition analyses supported the use of the FIML estimator. Prior to testing the model in Figure 1, we investigated the adequacy of the measurement model. We then examined the model without the moderator variable (discrimination) to test the socioeconomic disadvantage → harsh parenting → anger → commitment pathway. We then conducted a multigroup SEM to examine youth-reported Wave 4 discrimination to see if it moderated the harsh parenting → anger pathway. The significance of indirect effects was tested using the delta method to compute standard errors (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2013).

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) of the harsh parenting, anger, and commitment–behavior constructs revealed a good fit to the data, χ2(23) = 26.15, p = .29. CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .02 (0, .05). Factor loadings for the manifest variables on their respective constructs are presented in Table 2. Correlations among study variables and their means and standard deviations are provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings from CFA

| Variables | Scales | Lambda | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harsh parenting (Ages 11–13) | Harsh-inconsistent parenting (W1–W3) | .41 | < .001 |

| Nurturant-supportive parenting (W1–W3) | −.66 | < .001 | |

| Interaction behavior questionnaire (W1–W3) | −.49 | < .001 | |

|

| |||

| Anger (Ages 16–18) | State Anger (W4) | .82 | < .001 |

| State Anger (W5) | .74 | < .001 | |

| State Anger (W6) | .73 | < .001 | |

|

| |||

| Commitment related behavior (Ages 19–21) | High-quality romantic relationship present (W7–W9) | .50 | < .001 |

| Infidelity in current or past year relationship (W7–W9) | −.46 | < .001 | |

| 2+ sexual partners in past 3 months (W7–W9) | −.46 | .001 | |

Table 3.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics among Study Variables

| Study Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Socioeconomic disadvantage | — | |||||||||||

| 2. Behavior problems | .17** | — | ||||||||||

| 3. Harsh parenting | .04 | .13* | — | |||||||||

| 4. Nurturing parenting | −.06 | −.12 | −.16** | — | ||||||||

| 5. Relationship harmony | −.19** | −.24*** | −.30*** | .33*** | — | |||||||

| 6. Anger (age 16) | .07 | .10 | .21** | −.25*** | −.25*** | — | ||||||

| 7. Anger (age 17) | .04 | .06 | .09 | −.17** | −.22*** | .56*** | — | |||||

| 8. Anger (age 18) | .04 | .09 | .12* | −.21** | −.20** | .58*** | .63*** | — | ||||

| 9. Racial discrimination | .01 | .14* | .11 | −.11 | −.19** | .40*** | .41*** | .42*** | — | |||

| 10. Committed relationships | −.12 | −.09 | −.10 | .06 | .17* | −.27** | −.17 | −.08 | −.01 | — | ||

| 11. Relationship infidelity | .09 | .12 | .08 | .06 | −.12 | .23** | .18* | .11 | .11 | −.21** | — | |

| 12. Relationship promiscuity | −.05 | .05 | .09 | −.07 | −.07 | .23** | .18** | .18** | .16* | −.18* | .49*** | — |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | 6.61 | 1.02 | 6.81 | 28.03 | 17.09 | 31.79 | 32.95 | 31.71 | 3.67 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.94 |

| SD | 3.89 | 0.44 | 1.12 | 3.08 | 2.37 | 10.60 | 12.05 | 10.49 | 3.51 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.98 |

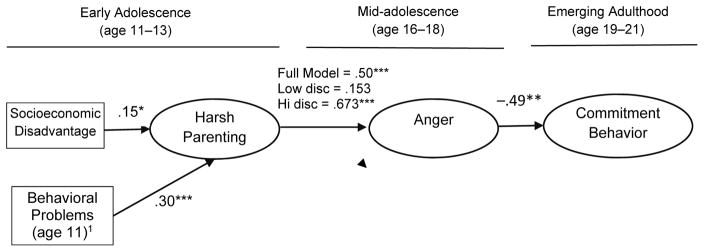

We next examined hypothesized predictors of commitment behavior without the moderating variable of racial discrimination. Results are presented in Figure 2. Controlling for the influence of behavior problems at Wave 1, socioeconomic disadvantage significantly predicted harsh parenting practices in early adolescence (β = .15, p < .05). Harsh parenting in early adolescence predicted youths’ reports of anger in mid-adolescence (β = .50, p < .001; full model), which in turn predicted negatively emerging adult commitment behavior (β = –.49, p < .01). Indirect-effect analysis results are presented in Table 4. The indirect effect linking socioeconomic disadvantage to commitment-related behavior through harsh parenting and anger was not significant (p = .11). Indirect-effect analysis of the influence of harsh parenting on commitment behavior via anger, however, was significant (p = .025). This suggests that anger is a mediating mechanism linking harsh parenting in early adolescence to commitment-related behavior in emerging adulthood.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model Results Predicting Commitment-Related Behavior. Disc = Discrimination.

1All endogenous constructs were controlled, however, nonsignificant paths are not pictured.

Disc = discrimination.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects

| Predictors | Mediator(s) | Outcomes | Indirect Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Estimates | SE | p | |||

| Total Sample | |||||

|

| |||||

| Socioeconomic | Harsh parenting | Anger | 0.170 | 0.080 | .033 |

| Behavior problems | Harsh parenting | Anger | 1.262 | 0.409 | .002 |

| Harsh parenting | Anger | Commitment | −0.283 | 0.127 | .025 |

| Socioeconomic | Harsh parenting | Commitment | −0.002 | 0.005 | .637 |

| Socioeconomic | Anger | Commitment | 0.002 | 0.005 | .678 |

| Socioeconomic | Harsh parenting/Anger | Commitment | −0.005 | 0.003 | .109 |

| Behavior problems | Harsh parenting | Commitment | −0.017 | 0.036 | .635 |

| Behavior problems | Anger | Commitment | 0.010 | 0.024 | .662 |

| Behavior problems | Harsh parenting/Anger | Commitment | −0.037 | 0.019 | .048 |

|

| |||||

| High Racial Discrimination Group | |||||

|

| |||||

| Socioeconomic | Harsh parenting | Anger | 0.250 | 0.122 | .041 |

| Behavior problems | Harsh parenting | Anger | 1.489 | 0.552 | .007 |

| Harsh parenting | Anger | Commitment | −0.433 | 0.177 | .014 |

| Socioeconomic | Harsh parenting | Commitment | −0.004 | 0.005 | .518 |

| Socioeconomic | Anger | Commitment | −0.001 | 0.005 | .824 |

| Socioeconomic | Harsh parenting/Anger | Commitment | −0.009 | 0.006 | .099 |

| Behavior problems | Harsh parenting | Commitment | −0.021 | 0.033 | .525 |

| Behavior problems | Anger | Commitment | 0.013 | 0.024 | .683 |

| Behavior problems | Harsh parenting/Anger | Commitment | −0.054 | 0.028 | .049 |

In a multigroup model, we considered the influence of racial discrimination at Wave 4 (age 16) on the association between harsh parenting and youths’ anger. Groups were compared using a median split on the racial discrimination measure. For young men in the low discrimination group, no significant effect emerged between harsh parenting and anger (β = .15, ns). Conversely, in the high discrimination group, a large effect emerged (β = .67, p < .001). The chi-square difference test was significant, Δχ2 (1) = 12.415, p < .001, indicating moderation. Indirect-effect analysis of the harsh parenting → anger → commitment pathway was significant for the high discrimination group (estimates = −0.444, SE = 0.176, p = .011), but not for the low discrimination group (estimates = −0.096, SE = 0.081, p = .235). This indicates the presence of moderated mediation; in the presence of discrimination, anger is a mediator of the influence of harsh parenting on commitment behavior. This pathway emerged while controlling for the influence of antecedent behavior problems, which also exerted a significant influence on the harsh parenting → anger → commitment path.

Discussion

During the emerging adult years, involvement in high quality, committed, romantic relationships signals the development of psychosocial maturity and the ability to engage in intimate relationships that presage behavior in future family relationships (Karney et al., 2007). For African American men growing up in socioeconomically disadvantaged environments, low levels of relationship commitment may forecast low involvement with enduring marriages. To date, little research has addressed the development of commitment-related behavior among African American men. Informed by research documenting the challenges that socioeconomically disadvantaged environments confer on couples’ relationships and the developmental influence of parent–youth relationships on such relationships among emerging adults, we investigated the pathways connecting challenging socioeconomic environments and exposure to harsh parenting to young African American men’s commitment-related behavior. We considered the potential stress-amplifying effect of racial discrimination in the link between parenting and adolescent anger, a proximal predictor of men’s commitment-related behavior.

Results were largely consistent with our hypotheses. Controlling for the influence of behavior problems, socioeconomic disadvantage predicted harsh, unsupportive parenting practices in early adolescence, which in turn affected men’s anger in mid-adolescence and commitment-related behavior in emerging adulthood. Indirect-effect analysis revealed that anger mediated the influence of harsh parenting and behavioral problems on emerging adult commitment-related behavior. Consideration of the moderating influence of racial discrimination added considerably more precision to our understanding of the influence of parenting on anger. For young men with little exposure to racial discrimination, harsh parenting was not a significant predictor of mid-adolescent anger. In the high discrimination group, however, the influence of harsh parenting was amplified to yield a particularly large effect (β = .67, p < .001). Indirect-effect analysis indicated the operation of moderated mediation; in the presence of discrimination, anger mediated the influence of harsh parenting on commitment behavior.

Our approach to the conceptualization and assessment of commitment-related behavior was unique. We integrated emerging adult men’s reports across three annual assessments that addressed (a) involvement in high-quality romantic relationships, (b) sexual fidelity in relationships, and (c) involvement in multiple sexual partnerships. This approach integrates perspectives from emerging adult development (committed, high-quality relationships) and from research on men’s sexual health (serial monogamy versus concurrent or multiple sexual partnerships). CFA and affirmative findings as presented in Figure 2 supported the validity of this approach to commitment-related behavior.

Past studies have linked commitment-related behavior and socioeconomic disadvantage (Kogan, Lei, et al., 2013). African Americans are disproportionately exposed to disadvantaged environments, which takes a toll on even the most concerned parents’ childrearing behavior. Stressors that accompany socioeconomic disadvantage make engagement in consistent, warm parenting practices difficult. We hypothesized that parent-reported socioeconomic stressors would predict their use of harsh, unsupportive parenting practices when youths were in early adolescence (ages 11 through 13 years). Consistent with prior research (Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, & Jones, 2001; Scaramella et al., 2008), socioeconomic risks were associated significantly, though modestly, with parenting characterized by elevated levels of harsh and inconsistent discipline, low levels of nurturance, and poor relationship quality. This effect was present independent of the influence of child behavioral problems at age 11 years, which was a strong predictor of parenting behavior. Notably, this replication of past findings was revealed using a multi-reporter measurement strategy that integrated parent and youth reports across three early-adolescent time points.

We further hypothesized that youths’ exposure to socioeconomic disadvantages and harsh parenting would carry forward to influence commitment-related behavior in emerging adulthood, particularly for young men exposed to racial discrimination. Informed by research on emotion regulation, we found that harsh parenting forecast youth anger across mid-adolescence, and that anger mediated the link between harsh, unsupportive parenting and commitment-related behavior in emerging adulthood. Harsh, unsupportive parenting is a hallmark of risky family environments, which are implicated in a range of negative development and health outcomes (Brody et al., 2014; Repetti et al., 2002). Research suggests that emotion regulation in particular plays a prominent role in determining how the influence of family risk carries forward in adolescence, as young people begin to spend increasing amounts of time with peers and in the community (Bell & Calkins, 2000; Brody et al., 2014; Wills, Sandy, Shinar, & Yaeger, 1999). The role of anger as a carry-forward mechanism is consistent with recent findings indicating that aversive interactions with parents induce negative emotional states, problems with anger management, and hostile attribution biases (Powers & Trust-Schwartz, 2012; Simons et al., 2014). An emerging body of research investigating family relationships, attribution processes, and negative emotions supports perspectives on working models of relationships and negative emotions (Cooper, Shaver, & Collins, 1998; Simpson, Collins, Tran, & Haydon, 2007). For youths raised in harsh environments, the potential for angry responses and negative emotional states reflects a cognitive orientation that is reinforced by ongoing interactions. These patterns may occur in a variety of relationships. Some studies, however, suggest that intimate romantic relationships in particular activate negative emotions due to their relevance in the formation of working models of relationships and are, in turn, influenced by angry mood states and expressions (Diamond & Hicks, 2005; Overall et al., 2014).

In considering contextual challenges specific to African American men, we hypothesized that exposure to racial discrimination in adolescence would exacerbate the influence of harsh parenting on anger. Although relatively few studies address this hypothesis directly, our conjecture was informed by theories regarding the multiplicative influence of specific stressors and the unique influence of discrimination on male African Americans during adolescence (Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Burrow, 2009; Watkins, 2012). Several studies show that young African American men report more exposure to discrimination than do young African American women and are more affected by that exposure (Brody, Kogan, & Chen, 2012; Kessler et al., 1999). Supportive parenting has been shown to have a powerful influence in buffering youths from the negative outcomes of discrimination. Therefore, when parent–youth relationships are conflicted, no protection is available from a key environment; for a young person, environments both inside and outside the family may seem hostile and unsupportive. The results of our test confirmed that racial discrimination exacerbated the influence of harsh parenting on anger. In the presence of high levels of discrimination, the effect of aversive parenting on anger was large (β = .67, p < .001); in contrast, when discrimination levels were low, harsh parenting was not a significant predictor of youth anger (β = .15, ns). The size of this effect across different developmental phases, using multi-reporter, multi-time-point assessments, and controlling for antecedent behavior problems suggests a particularly powerful influence on development. The multiplicative influence of these two risk factors is consistent with Murry et al.’s (2001) findings with rural African American mothers, as well as with Ong et al.’s (2009) perspective that the amplification of other risks in a young person’s environment is an important pathway for understanding the effects of discrimination. Because few studies have addressed discrimination as an amplifier of other stressors, additional research is warranted.

Study findings support the contention that the combination of harsh parenting and racial discrimination is a powerful antecedent of young men’s commitment-related behavior. Indirect-effect analysis supports a moderated mediation model. The indirect effect of parenting → anger → commitment was present only when youths were exposed to high levels of racial discrimination. Indirect-effect analyses also provided insight into a number of interesting issues. Youths’ problem behaviors and exposure to low-SES environments at age 11 affected their anger in mid-adolescence by increasing the likelihood that they would experience harsh parenting. Even the most concerned parents may have difficulty in providing monitoring, support, and consistent discipline when dealing with the challenges of poverty and child behavior problems. Accounting for behavior problems in the design supports the robustness of the moderated mediation findings, because behavior problems associated with anger and aggression may constitute a plausible alternative to the influence of discrimination and harsh parenting as an explanation for anger in mid-adolescence.

From a prevention perspective, this study underscores the importance of intervening with youths during early adolescence to forestall problems associated with poverty. Intervention efforts designed to enhance parenting practices in early adolescence in general, and those that may protect developing youths from the influence of discrimination in particular, can have downstream effects on men’s intimate relationships and family formation processes. Such interventions may target parenting practices, such as racial socialization, that have been demonstrated to buffer youths from discrimination as well as teaching youths skills for coping with this stressor. Examples of efficacious interventions that target these practices include the Strong African American Families program (SAAF; Brody, Kogan, & Grange, 2012) for preadolescents and the SAAF–Teen program (Kogan et al., 2012) for middle adolescents. These programs capitalize on parental involvement to increase active racial socialization and family support to help youths develop a positive racial self-concept. These and other programs, such as Life Skills Training (Botvin & Griffin, 2004), also target the use of problem-solving–oriented coping to help youths develop strategies for achieving their future goals despite discrimination. From a policy perspective, low-SES environments should continue to be a focus of efforts to counteract poverty and support effective parenting practices among often-overstressed parents. Importantly, this research represents one of a number of recent well-designed longitudinal studies that document the presence and pernicious influence of racial discrimination, particularly microstressors (Brody et al., 2006; Kogan, Yu, Allen, & Brody, 2015). The everyday lives of many young Black teens, particularly male youths, involve routine experiences with demeaning treatment that take a severe toll on development (Brody et al., 2006) .

Strengths and Limitations

Hypotheses regarding the pathways linking socioeconomic disadvantage and harsh, unsupportive parenting to commitment-related behaviors were tested with young men who provided data at nine time points spanning early adolescence, mid-adolescence, and emerging adulthood. Data from parents and teachers were used to measure variables during early adolescence, and the assessment of harsh parenting included reports on multiple measures from both parents and youths. Teachers assessed control variables and behavior problems. Key construct data from three time points were used, creating a highly reliable assessment of SES risk, parenting behavior, youth anger, and youth commitment-related behavior.

Despite these strengths, a number of limitations must be noted. Because of a dearth of literature examining the unique development of male African Americans, we focused exclusively on this group for analysis. Results cannot be generalized to female youths. The participants lived in resource-poor rural environments; thus, the findings also cannot be generalized to youths in urban areas. Finally, our assessment of relationship quality relied on participants’ self-reports. Studies operationalizing relationship commitment using both partners’ perspectives provide a more complete account of relationship behavior. Although measures of antecedent anger would have been desirable, anger was not assessed in early adolescence. Teacher reports of behavior problems, however, provided a robust characterization of individual youths’ anger-associated conduct that could constitute a plausible alternative to the influence of discrimination and harsh parenting as an explanation for anger in mid-adolescence. These limitations notwithstanding, this study used a sophisticated measurement plan with longitudinal data to demonstrate how SES, harsh parenting, and racial discrimination affect commitment-related behavior through the proximal mechanism of youth anger.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman BP, Brown ED, Izard CE. The relations between contextual risk, earned income, and the school adjustment of children from economically disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:204–216. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.204. http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FEA, Donaldson KH, Fullilove RE, Aral SO. Social context of sexual relationships among rural African Americans. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28:69–76. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Marital quality in African American marriages. Oklahoma City, OK: National Healthy Marriage Resource Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Brody GH. A fraught passage: The identity challenges of African American emerging adults. Human Development. 2008;51:291–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bell KL, Calkins SD. Relationships as inputs and outputs of emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:160–164. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1103_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. A different view of anger: The cognitive-neoassociation conception of the relation of anger to aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2012;38:322–333. doi: 10.1002/ab.21432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black KA, Schutte ED. Recollections of being loved: Implications of childhood experiences with parents for young adults’ romantic relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1459–1480. doi: 10.1177/0192513x06289647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright SR. The Georgia county guide. 28. Athens, GA: Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MHE, Bradley RHE. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW. Life skills training: Empirical findings and future directions. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25:211–232. doi: 10.1023/B:JOPP.0000042391.58573.5b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ. Role strain and adaptation issues in the strength-based model: Diversity, multilevel, and life-span considerations. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34:118–133. doi: 10.1177/0011000005282374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:267–283. doi: 10.1177/0146167295213008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Kogan SM, Murry VM, Logan P, Luo Z. Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2008;70:319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, … Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger R, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Simons RL. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Chen Y-f. Perceived discrimination and increases in adolescent substance use: Gender differences and mediational pathways. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1006–1011. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Grange CM. Translating longitudinal, developmental research with rural African American families into prevention programs for rural African American youth. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 553–570. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Beach SRH, Kogan SM, Windle M, Philibert RA. Harsh parenting and adolescent health: A longitudinal analysis with genetic moderation. Health Psychology. 2014;33:401–409. doi: 10.1037/a0032686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Evans GW, Beach SR, … Philibert RA. Cumulative socioeconomic status risk, allostatic load, and adjustment: a prospective latent profile analysis with contextual and genetic protective factors. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:913–927. doi: 10.1037/a0028847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy EF, Stevenson HC., Jr They wear the mask: Hypervulnerability and hypermasculine aggression among African American males in an urban remedial disciplinary school. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2005;11:53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2011. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61:1–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. In: Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, editors. New directions for child and adolescent development: No. 124. Coping and the development of regulation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Shaver PR, Collins NL. Attachment styles, emotion regulation, and adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:1380–1397. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Meunier LN. The influence of peer experiences on bravado attitudes among African American males. In: Way N, Chu JY, editors. Adolescent boys: Exploring diverse cultures of boyhood. New York: New York University Press; 2004. pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Mars DE, Burns LJ. The relations of stressful events and nonacademic future expectations in African American adolescents: Gender differences in parental monitoring. Journal of Negro Education. 2012;81:338–353. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Swanson DP, Hayes DM. School- and community-based associations to hypermasculine attitudes in African American adolescent males. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83:244–251. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Winter MA, Cicchetti D. The implications of emotional security theory for understanding and treating childhood psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology. 2006;18:707–735. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Hicks AM. Attachment style, current relationship security, and negative emotions: The mediating role of physiological regulation. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships. 2005;22:499–518. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65(Spec No. 2):649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Martínez LM, Caldwell CH, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Stressors in multiple life-domains and the risk for externalizing and internalizing behaviors among African Americans during emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:1600–1612. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9778-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Rose AJ. Friendships, romantic relationships, and peer relationships. In: Lerner RM, Lamb ME, editors. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 3. Social and emotional development. 7. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015. pp. 932–974. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA. Concordance in attachment states of mind and styles with respect to fathers and mothers. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1239–1247. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, O’Hara RE. Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2010;99:785–801. doi: 10.1037/a0019880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Manning WD. Gender and the meanings of adolescent romantic relationships: A focus on boys. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:260–287. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guyll M, Cutrona C, Burzette R, Russell D. Hostility, relationship quality, and health among African American couples. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:646–654. doi: 10.1037/a0020436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakulinen C, Jokela M, Hintsanen M, Pulkki-Råback L, Hintsa T, Merjonen P, … Keltikangas-Järvinen L. Childhood family factors predict developmental trajectories of hostility and anger: A prospective study from childhood into middle adulthood. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:2417–2426. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Herman-Stahl MA. Neighborhood safety and social involvement: Associations with parenting behaviors and depressive symptoms among African American and Euro-American mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:209–219. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WE., Jr . From shortys to old heads: Contemporary social trajectories of African American males across the life course. In: Johnson WE Jr, editor. Social work with African American males: Health, mental health, and social policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Beckett MK, Collins RL, Shaw R. Adolescent romantic relationships as precursors of healthy adult marriages: A review of theory, research, and programs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR488. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. doi: 10.2307/2676349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Brody GH, Molgaard VK, Grange C, Oliver DAH, Anderson TN, … Sperr MC. The Strong African American Families–Teen trial: Rationale, design, engagement processes, and family-specific effects. Prevention Science. 2012;13:206–217. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Lei MK, Grange CR, Simons RL, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Chen YF. The contribution of community and family contexts to African American young adults’ romantic relationship health: a prospective analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:878–890. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9935-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Yu T, Allen KA, Brody GH. Racial microstressors, racial self-concept, and depressive symptoms among male African Americans during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(4):898–909. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0199-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Yu T, Brody GH, Allen KA. The development of conventional sexual partner trajectories among African American male adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:825–834. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Conflict resolution styles in gay, lesbian, heterosexual nonparent, and heterosexual parent couples. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1994;56:705–722. doi: 10.2307/352880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Differences between partners from black and white heterosexual dating couples in a path model of relationship commitment. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships. 2008;25:51–70. doi: 10.1177/0265407507086805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The Schedule of Racist Events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. doi: 10.1177/00957984960222002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA, Dodge KA. The development of anger and hostile interactions. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, editors. Handbook of emotions. 3. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 730–741. [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Chase-Lansdale PL. Sexual intercourse and pregnancy among African American girls in high-poverty neighborhoods: The role of family and perceived community environment. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2001;63:1146–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brown AP, Brody GH, Cutrona CE, Simons RL. Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning, and family relationships. Journal of Marriage &Family. 2001;63:915–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00915.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5. Los Angeles: Author; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Burrow AL. Racial discrimination and the stress process. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2009;96:1259–1271. doi: 10.1037/a0015335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Girme YU, Lemay EP, Jr, Hammond MD. Attachment anxiety and reactions to relationship threat: The benefits and costs of inducing guilt in romantic partners. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2014;106:235–256. doi: 10.1037/a0034371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2001;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SR, Trust-Schwartz R. Influence of caregiver punishment for anger and caregiver modeling of distributive aggression on adult anger expression in romantic relationships. Southern Communication Journal. 2012;77:128–142. doi: 10.1080/1041794X.2011.610492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Foster S, Kent RN, O’Leary KD. Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1979;12:691–700. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social enviornments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Fiese BH. Models of development and developmental risk. In: Zeanah CHJ, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. 2. New York: Guilford; 2000. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K, Settles-Reaves B, Walker D, Brownlow J. Social inequality and racial discrimination: Risk factors for health disparities in children of color. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S176–S186. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Neppl TK, Ontai LL, Conger RD. Consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage across three generations: Parenting behavior and child externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:725–733. doi: 10.1037/a0013190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Overbeek G, Vermulst A. Parent-child relationship trajectories during adolescence: Longitudinal associations with romantic outcomes in emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban M. Sexual partner concurrency among STI clinic patients with a steady partner: Correlates and associations with condom use. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85:343–347. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.035758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Connolly J. The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1:27–39. doi: 10.1177/2167696812467330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Simons RL, Landor AM, Bryant CM, Beach SRH. Factors linking childhood experiences to adult romantic relationships among African Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:368–379. doi: 10.1037/a0036393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Burt CH. Learning to be bad: Adverse social conditions, social schemas, and crime. Criminology. 2011;49:553–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummund H, Stewart E, Brody GH, … Cutrona C. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2006;47:373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Lei MK, Landor AM. Relational schemas, hostile romantic relationships, and beliefs about marriage among young African American adults. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships. 2012;29:77–101. doi: 10.1177/0265407511406897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, Haydon KC. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2007;92:355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Resiliency and fragility factors associated with the contextual experiences of low-resource urban African-American male youth and families. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does it take a village? Community effects on children, adolescents, and families. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Cunningham M, Swanson DP. Identity as coping: Adolescent African-American males’ adaptive responses to high-risk environments. In: Griffith EH, Blue HC, Harris HW, editors. Racial and ethnic identity: Psychological development and creative expression. Florence, KY: Routledge; 1995. pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory–2: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Varner F, Mandara J. Differential parenting of African American adolescents as an explanation for gender disparities in achievement. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24:667–680. doi: 10.1111/jora.12063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon-Feagans L, Garrett-Peters P, De Marco A, Bratsch-Hines M. Children living in rural poverty: The role of chaos in early development. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 448–466. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC. Depression over the adult life course for African American men: Toward a framework for research and practice. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;6:194–210. doi: 10.1177/1557988311424072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013;57:1152–1173. doi: 10.1177/0002764213487340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O, Yaeger A. Contributions of positive and negative affect to adolescent substance use: Test of a bidimensional model in a longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:327–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.13.4.327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly RC, Morris LV. The Southern Black Belt: A national perspective. Lexington, KY: TVA Rural Studies Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]