Abstract

The percentage of young American adults residing in their parents’ home has increased markedly over recent years, but we know little about how sociodemographic, life-course, and parental characteristics facilitate or impede leaving or returning home. We use longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Transition into Adulthood survey to examine the determinants of leaving and returning home among youth who turned age 18 between 2005 and 2011. Findings from event history models show that while leaving and returning home is to some extent a function of normative life-course transitions, characteristics of the parental home (e.g., presence of co-resident siblings, mother’s educational attainment) and the degree of family connectivity (e.g., emotional closeness to mother, instrumental help from family) also play important roles. Experiencing physical, including sexual, victimization drives young adults both out of, and back into, the parental home. Having parents in poor physical health encourages young adults to move back home. Overall, the results suggest that a comprehensive explanation for both home-leaving and home-returning will need to look beyond life-course transitions and standard economic accounts to encompass a broader array of push and pull factors, particularly those that bond young adults with their parents.

Keywords: Leaving home, returning home, boomerang kids, migration, transition to adulthood

One of the most prominent changes in the structure and composition of U.S. households over recent years has been a sharp increase in the percentage of young adults residing in the parental home (Qian 2012). Between 2000 and 2011, the percentage of men ages 25 to 34 living with their parents rose from 12.9% to 18.6% (Mather 2011). The increase in the percentage of women in this age range living with their parents was somewhat less dramatic but also nontrivial—from 8.3% to 9.7%. This recent surge in the percentage of young adults living at home is in some ways a continuation of a longer historical trend in the residential behavior of adolescents and younger adults (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1999). For example, between 1960 and 2010, the percentage of women ages 18 to 25 living at home increased from 35% to 49%; the comparable percentage of men rose from 52% to 57% (Payne 2011).

Yet, despite the acknowledged importance of parent-child coresidence for young adult well-being (Furstenberg 2010; White 1994), we know little about the contemporary dynamics and determinants of young adults’ propensity to move out of and, especially, back into the parental home. Trends in the percentage of young adults living at home, usually derived from decennial census or cross-sectional surveys, are incapable of identifying the events in young adults’ life-course that may precipitate either home-leaving or home-returning, nor can they examine how characteristics of the parental home and parent-child social relationships influence the timing at which children leave home or, once having left, the likelihood that they return.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the contemporary determinants of leaving and returning to the parental home among a nationally-representative cohort of American youth. We use prospective, longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Transition into Adulthood (PSID-TA) module, which follows a sample of adolescents and young adults from 2005 to 2011. Our analysis goes beyond prior studies of home-leaving and home-returning mainly by focusing on a historical period bracketing the Great Recession, which may have altered young adults’ residential decision-making; by considering a much broader array of potential determinants of leaving and returning home, including many not heretofore examined; by taking measures of these influences from both young adults and directly from their parents; and by estimating parallel models of both leaving and returning home. Our theoretical framework incorporates conventional accounts that emphasize the salience of normative life-course transitions (e.g., Buck and Scott 1993) and access to socioeconomic resources (e.g., Avery et al. 1992) for young adults’ living arrangements, but also considers as potential influences characteristics of the household and family of origin, multiple dimensions of connectivity between young adults and their parents, exposure to adverse life events, and the temporal and geographic context. As such, our analysis provides an unusually comprehensive and timely depiction of the key forces that shape young adults’ decision to leave and return to their parental home.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Although there exists no unified theory of why young adults leave or return to the parental home, the life course perspective provides a useful framework for exploring this issue (Putney and Bengston 2003). The life course is defined as a “sequence of socially defined events and roles that the individual enacts over time” (Giele and Elder 1998:22). Several principles of the life course perspective appear particularly germane to the study of young adults’ home-leaving behavior. The life course perspective acknowledges the possibility of transition reversals, or counter-transitions, a prime example of which is young adults returning to live with their parents after having previously established an independent household (Shanahan 2000). The life course principle of heterogeneity (Mitchell 2003) acknowledges the substantial inter-individual variation in the timing of leaving and returning to the parental home. Some of this variation may be patterned and structured, reflecting young adults’ differential access to the resources needed to establish and maintain an independent household; other parts of the variation could stem from unexpected and largely unpredictable shocks that alter life course trajectories, such job loss, the dissolution of a cohabiting partnership, illness, or a serious criminal victimization. The life course principle of linked lives (Elder et al. 2003) emphasizes how characteristics of, and events occurring to, members of shared social networks influence the timing of critical life course events; in the context of home-leaving, this tenet directs particular attention to how parental characteristics and the quality of parent-child social relationships influence both the timing of leaving home and the likelihood of returning. And the life course principle of socio-historical and geographic location (Mitchell 2003) emphasizes how individual lives unfold in the context of broader events. As noted above, the Great Recession is one such event that is believed to have altered established patterns of home-leaving and home-returning.

Yet, while the life course approach provides a metatheoretical perspective for exploring the timing at which young adults leave and return home, it remains more of an orienting framework than a set of interrelated, falsifiable hypotheses (Elder et al. 2003; Mayer 2009). Moreover, two different life course principles could direct attention to the same potential determinant of leaving or returning home. Consequently, rather than organize possible explanations for leaving and returning home around life course principles, we organize them around more substantive themes. These themes are not necessarily mutually exclusive but rather reflect different emphases. Young adults’ decision to leave or return to the parental home is likely to be multifaceted, driven not only by life-course events and economic exigencies, but also by the relative attractiveness of living in the parental home versus living independently.

Concurrent Life-course Transitions

The life course perspective emphasizes interconnections among key events in individuals’ lives (Elder et al. 2003). And indeed, arguably the dominant approach to studying the determinants of home-leaving and home-returning views moves out of and, to a lesser extent, back into the parental home as consequences of concurrent, normative transitions in the young adult life course. Starting college or getting a job frequently necessitates relocating geographically in order to live close to school or place of employment (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1999). Getting married or entering a cohabiting union encourages setting up a separate household to create privacy (Smits et al. 2010), although over time marriage has become a less frequent route for leaving the parental home (Goldscheider et al. 1999) relative to attending college or living independently (Thornton et al. 1993). Becoming a parent appears to raise the risk of leaving home but more so for women than for men (Goldscheider et al. 2014).

Similarly, returns to the parental home are often driven by changes in young adults’ social and economic roles. Unsurprisingly, moving back home is often caused by “failure” transitions, such as losing a job or dissolving a romantic partnership (DaVanzo and Goldscheider 1990). But such moves may also be facilitated by the successful completion of transitory roles, such as graduating from college or finishing military service. Moving back home after the completion of transitory roles may be particularly common in an economic climate where jobs are scarce and it is therefore difficult to maintain a separate household. In Stone et al.’s (2014) recent analysis of British data, even youth who found employment following graduation from college were more likely to move back home than youth who remained in school or were consistently employed. Young adults with children are generally less likely than childless youth to return home, provided that the marital or cohabiting union (if any) remains intact (Stone et al. 2014). In general, then, we expect to find that the timing of both home-leaving and home-returning will be associated with coincident changes in young adults’ economic roles and romantic relationships. College matriculation and entering a cohabiting union are likely to be particularly important for leaving home, while finishing college and dissolving a romantic union may be especially important for returning home.

Socioeconomic Resources

Young adults’ differential access to the financial resources needed to establish and maintain a separate household provides another explanation for life course heterogeneity in the timing of home-leaving and home-returning (Goldscheider 1997; Whittington and Peters 1996). Economic independence is likely to facilitate residential independence (Furstenberg et al. 2005). In contrast, without steady employment and adequate incomes, youth are unable to pay for rent, utilities, food, and other basics of daily living. Consequently, young adults lacking sufficient incomes to live independently will be less likely to move out of and more likely to move back to the parental home. Young adults living independently have higher rates of employment and higher earnings than those who reside with their parents (Payne and Copp 2013), and those with poor employment prospects exhibit high rates of moving back home once having lived independently (Kaplan 2012). Sironi and Furstenberg (2012) suggest that the deteriorating economic opportunities and attendant reduction in self-sufficiency faced by young adults may partly explain the decline in home-leaving over recent decades. We hypothesize that greater individual socioeconomic resources will hasten home-leaving and deter home-returning.

Parental Family and Household Characteristics

A third category of potential influences on the timing at which young adults leave and return to the parental home focuses on characteristics of the parental home itself. Viewed from the life course perspective, the role of these characteristics broadly illustrates the principles of inter-individual heterogeneity and linked lives. Two attributes of the parental family have received particular attention—family structure and economic status. In general, growing up in a so-called “disrupted” family—one without both biological parents present—tends to hasten home-leaving, particularly to autonomous living and to marriage (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1998), but less so to attend college. Prior research suggests that childhood family structure does not affect the likelihood that young adults move back to the parental home once having achieved residential independence (Goldscheider et al. 1999).

Parental socioeconomic resources likely bear complex associations with young adults’ home-leaving and home-returning behavior. On the one hand, transferable resources such as income and wealth afford youth greater opportunity to attend college or to live autonomously; some (e.g., Avery et al. 1992) but not all studies (e.g., Buck and Scott 1993) find a positive association between family income and early home-leaving. Prior research is also somewhat inconsistent regarding the influence of parental socioeconomic status on home-returning, with some studies (Mulder and Clark 2002) but not others (Goldscheider et al. 1999) finding that the likelihood of returning home increases with parental income. Parental education might also matter, as more-educated parents are likely to instill in their children a planful competence that the life course perspective views as critical to a successful transition to adulthood (Clausen 1991).

On the other hand, nontransferable parental resources may incentivize youth to remain at home or to return there. For example, housing quality, especially as reflected in homeownership (Gierveld et al. 1991), might shape the relative attractiveness of the parents’ dwelling and thus facilitate or impede young adults’ decision to leave or return to the parental home. Less attention has been given to other aspects of the parental home that might shape its attractiveness to young adults. One such characteristic is the presence of adult siblings, which likely signals a higher level of familism and parents’ willingness to coreside with an adult child, and well as increased competition for parental resources (Zorlu and Mulder 2011). In sum, we expect that a disrupted parental family structure will hasten home-leaving and deter home-returning, that parental socioeconomic resources will either encourage or discourage youth to leave or return home depending on the transferability of those resources, and that the presence of adult siblings in the parental home will delay home-leaving but increase the likelihood of returning home.

Family Connectivity

The life course principle of linked lives calls attention to the economic and psychosocial connections between young adults and their parents as possible influences on young adult home-leaving and home-returning. Although less often studied than other influences, the existence and strength of young adults’ social, emotional, and instrumental ties to their family are likely to influence decisions to leave and/or return home (White 1994). Adolescents and young adults who enjoy close personal relationships with their parents are likely to be less motivated to leave and more motivated to return (Goldscheider et al. 2014). Once having left, young adults who receive financial support from their parents may be better able to sustain an independent living situation and therefore less likely to move back home (Mitchell et al. 2004). At the same time, young adults who report being mainly responsible for their own day-to-day living expenses may have attained sufficient financial independence from their origin families to live autonomously.

Strong social and emotional ties to their families of origin may also lead young adults to remain in or move back to the parental home when faced with adverse life events. For example, to more easily receive care from family members, young adults in poor physical health may be less likely than their healthier counterparts to leave the parental home and more likely to move back. Similarly, some young adults may opt to remain in or return to the parental home in order to care for parents in poor health (Smits et al. 2010). Among those living independently, experiencing a traumatic physical (including sexual) victimization might encourage young adults to seek the comfort and safety of the parental home. How a physical victimization might influence the risk of leaving the parental home is less clear. On the one hand, young adults who have recently been physically assaulted may be reluctant to establish an independent household that, unlike the parental home, is likely to lack potential guardians. On the other hand, as with the migratory response of households in general, victimization may encourage young adults to leave the parental neighborhood—and hence the parental home—for presumably safer environments (Dugan 1999; Xie and McDowall 2008). Victimization at the hands of parents or other family members would presumably be especially likely to spur home-leaving. In sum, we expect that leaving home will be positively associated with the extent to which youth receive instrumental help from their family of origin and inversely associated with emotional closeness to their parents and both their parents’ and their own poor health; the likelihood of returning home should exhibit the opposite associations. Experiencing a physical victimization is likely to encourage returning home, but could either delay or accelerate leaving home.

Temporal and Geographic Context

A final perspective on the determinants of leaving and returning to the parental home draws from the life course perspective’s emphasis on the salience of temporal and geographic context. As noted above, the 2007–2009 Great Recession may have significantly delayed home-leaving and encouraged home-returning by making it difficult for youth to find the type of job that would enable them to establish and maintain their own household (Newman 2012; Payne and Copp 2013). Economic uncertainty may also have reduced young adults’ ability to marry, thus narrowing this pathway for leaving home (Qian 2012). And, although most of the respondents in our study would be renting their dwelling if living independently, the collapse of the housing market and tightening of credit standards would render purchasing a home almost impossible for those who desired to do so.

Given these impacts of the Great Recession, we would expect declines over time in the rate at which young adults leave the parental home but, conditional upon having moved out, increases in the rate at which they return. Less clear is whether these trends can be attributed to changes in other measured covariates of young adults’ residential mobility, such as their declining transition to economic independence (Sironi and Furstenberg 2012) or their increasingly delayed transitions to marriage (Goldscheider et al. 1999). An inability of observed trends in young adults’ life course transitions, including employment and marriage, and access to socioeconomic resources to explain early 21st century trends in moving out and moving back may suggest that such trends were driven less by the economic difficulties created by the Great Recession and more by changes in attitudes and norms regarding the acceptability of parent-child coresidence (Settersten 1998). The increasing acceptance of an elongated period of “emerging adulthood” (Arnett 2004) may find expression in more positive views of coresidence on the part of both young adults and their parents and an attendant reduction in preferences for independent living.

Rates of leaving and returning to the parental home are also likely to vary geographically, mainly as a function of the affordability of independent living (Ermisch 1999; Hughes 2003). Where housing costs are high—for example, in large metropolitan areas and in the Northeast region of the country (Buck and Scott 1993)—young adults will face greater difficulty establishing and maintaining an independent household. Consequently, young adults may be less likely to move out, but more likely to move back, in these types of areas. Conversely, we anticipate higher rates of leaving the parental home and lower rates of returning to it in smaller metropolitan areas, in rural areas, and in geographic regions outside of the Northeast.

DATA AND METHODS

Data for this study come mainly from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics Transition into Adulthood survey (PSID-TA). The PSID-TA collects data from all children age 18 and older who had participated in the PSID’s Child Development Supplement and whose families were still participating in the main PSID (PSID 2011). The first interviews were conducted in 2005, with subsequent waves in 2007, 2009, and 2011 (the most recent year of available data). The response rate for the 2011 wave (among those eligible to be interviewed) was 92%. Our analysis uses data from the 2005 to 2011 waves when respondents were between the ages of 18 and 26. Because the measurement of the dependent variables and some of the independent variables requires data from successive interviews, our sample includes all PSID-TA respondents who were interviewed in at least two consecutive waves during this span (N = 1,521).

Dependent variables

Our analysis includes two dependent variables: the timing of moving out of the parental home and the timing of moving back to the parental home. In our discrete-time event-history models, the timing of these events is captured by binary variables indicating whether the respondent moved out or back between successive interviews, among those at-risk of experiencing each event. At each interview, PSID-TA respondents are asked where they lived most of the time during the previous fall and winter. Possible responses included parents’ home (house or apartment), apartment or house that the respondent (or the respondent’s parents’) rented or owned, and college dormitory, sorority, or fraternity. We contrast living in parents’ home with all other arrangements, which we refer to collectively as living independently. A recorded change in place of residence between successive PSID-TA interviews indicates either a move out of or back into the parental home.

We acknowledge that the use of a two-year mobility interval will miss short-term moves that occur entirely between interviews. For example, a young adult who leaves the parental home after the 2005 interview but returns prior to the 2007 interview will not be considered to have moved out of the parental home. Thus, our measurement strategy, like many survey-based studies of migration (e.g., Crowder et al. 2012), will undercount residential moves, and the influence of covariates that mainly affect short-term moves will be underestimated. However, sensitivity checks using a one year migration interval derived the main PSID household heads’ reports of the year that their child moved out of or back into the parental home yield generally similar findings to those using the two-year migration window derived from the PSID-TA respondents’ reports.

Independent variables

Most of the measures of the independent variables are taken from the PSID-TA respondents’ interviews, but some are taken from their parents’ interviews as part of the main PSID. Unless otherwise noted, values of the time-varying explanatory variables are taken from the interview that defines the beginning of each two-year migration interval. Table 1 provides a brief description of each independent variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables Used in Analysis of Moving Out and Back into the Parental Home by Residence at Origin: Transition into Adulthood Study, 2005–2011

| Variable | Description | Total | Living in Parental Home at t | Living Independently at t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Dependent Variables | |||||||

| Move out of parental home | 1=Moved out of parental home between t and t+2 | -- | .44 | -- | |||

| Move back into parental home | 1=Moved back into parental home between t and t+2 | -- | -- | .19 | |||

| Independent Variables | |||||||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | Respondent’s age in years at t | 20.16 | 1.97 | 19.53 | 1.90 | 20.79 | 1.84 |

| Female | 1=Respondent is female | .54 | .51 | .57 | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 1=Respondent is white | .47 | .41 | .53 | |||

| Black | 1=Respondent is black or African American | .40 | .44 | .35 | |||

| Hispanic or other races | 1=Respondent is Hispanic or other races | .13 | .15 | .12 | |||

| Life-course transitions | |||||||

| Primary activity transitions | |||||||

| High school to college | 1=In high school at t, in college at t+2 | .07 | .15 | .01 | |||

| Stable college student | 1= In college at t and t+2 | .18 | .12 | .23 | |||

| Stable working | 1=Working at t and t+2 | .28 | .26 | .30 | |||

| Stable idle | 1= Idle at t and t+2 | .05 | .06 | .04 | |||

| Student to working | 1=Student at t and working at t+2 | .17 | .15 | .19 | |||

| Student/working to idle | 1=Student or working at t, idle at t+2 | .09 | .10 | .07 | |||

| Working/idle to student | 1=Working or idle at t, student at t+2 | .09 | .09 | .09 | |||

| Idle to working | 1=Idle at t, working at t+2 | .07 | .07 | .06 | |||

| Relationship status transitions | |||||||

| Stable non-partnered | 1=Unmarried and not cohabiting at t and t+2 | .67 | .75 | .59 | |||

| Newly partnered | 1=Unmarried and not cohabiting at t, married or cohabiting at t+2 | .14 | .15 | .14 | |||

| Partnership dissolution | 1=Married or cohabiting at t, unmarried and not cohabiting at t+2 | .05 | .03 | .07 | |||

| Stable partnered | 1=Married or cohabiting at t, married and cohabiting at t+2 | .13 | .07 | .20 | |||

| Parenthood | 1=Has child(ren) at t | .19 | .15 | .22 | |||

| Socioeconomic resources | |||||||

| High school graduation or GED | 1= Has received high school degree or GED at t | .90 | .88 | .91 | |||

| Income | Respondent’s income in the calendar year preceding t (in logged thousands of 2004 dollars) | 1.45 | 1.18 | 1.34 | 1.32 | 1.56 | 1.22 |

| Receiving Welfare | 1=Receives payments from TANF, SSI, child support, or other source at t | .04 | .05 | .03 | |||

| Parental household and family characteristics | |||||||

| Household structure | |||||||

| Intact family | 1=Respondent resided with both biological parents at t | .50 | .48 | .52 | |||

| Biological and step parent | 1=Respondent resided with one biological and one step parent at t | .13 | .11 | .13 | |||

| Non-partnered biological parent | 1= Respondent resided with non-partnered biological parent at t | .37 | .40 | .34 | |||

| Mother’s education | Mother’s years of school completed when respondent was age 18 | 13.00 | 2.45 | 12.67 | 2.23 | 13.33 | 2.62 |

| Family income | Parents’ family income in the calendar year preceding t (in logged thousands of 2004 dollars) | 4.02 | .91 | 3.94 | .89 | 4.09 | .98 |

| Homeowner | 1=Parents own home at t | .71 | .68 | .73 | |||

| Coresident adult siblings | Number of adult siblings in parental home at t | .36 | .36 | .38 | .39 | .33 | .34 |

| Family connectivity | |||||||

| Help from family | Number of following five types of financial assistance received from family during prior 12 months at t: house/condo, rent/mortgage, personal vehicle, tuition, and expenses/bill | 1.08 | 1.17 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.28 |

| Personal responsibility scale | Responsibility taken on following four items on scale of 1 to 5 (1=Somebody else does this for me all the time, 5=I am completely responsible for this all the time) at t: earning own living, paying rent, paying bills, and managing money | 3.77 | 1.06 | 3.59 | 1.00 | 3.95 | 1.08 |

| Closeness to mother | Self reported emotional closeness to mother on a scale of 1 (not close at all) to 7 (very close) at t | 6.12 | 1.36 | 6.22 | 1.24 | 6.03 | 1.41 |

| Closeness to father | Self reported emotional closeness to father on a scale of 1 (not close at all) to 7 (very close) at t | 5.24 | 1.82 | 5.19 | 1.87 | 5.28 | 1.79 |

| Mother or father in poor health | 1=Either mother or father is in poor/fair health at t | .20 | .22 | .18 | |||

| Respondent in poor health | 1=Respondent is in poor/fair health at t | .08 | .08 | .07 | |||

| Physical victimization | 1=Respondent reports being physically victimized in past 2 years at t | .06 | .05 | .06 | |||

| Sexual victimization | 1=Respondent reports being sexually victimized in past 2 years at t | .02 | .02 | .02 | |||

| Temporal and geographic context | |||||||

| Year of observation | |||||||

| 2005 | 1=Migration interval begins in 2005 | .22 | .26 | .18 | |||

| 2007 | 1=Migration interval begins in 2007 | .34 | .33 | .34 | |||

| 2009 | 1=Migration interval begins in 2009 | .44 | .41 | .48 | |||

| Urbanization scale | Beale-Ross 10-point rural-urban continuum code for (1=completely rural, not adjacent to a metropolitan area, 10=central counties of metropolitan areas of 1 million+ population) for respondent’s residence at t | 7.67 | 2.32 | 7.64 | 2.37 | 7.69 | 2.30 |

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 1=Respondent lives in Northeast region at t | .13 | .13 | .13 | |||

| North Central | 1=Respondent lives in North Central region at t | .24 | .24 | .25 | |||

| South | 1=Respondent lives in South region at t | .45 | .48 | .43 | |||

| West | 1=Respondent lives in West region at t | .18 | .16 | .20 | |||

| N of person-periods | 2,997 | 1,506 | 1,491 | ||||

| N of persons | 1,521 | 1,068 | 918 | ||||

Note: t refers to beginning of migration interval, t+2 refers to end of migration interval. Standard deviations (SD) shown for continuous variables only.

Age is measured in the regression models by a series of dummy variables, with ages 17 and 18 combined serving as the reference. Following in large part the work of Stone et al. (2014), we capture the occurrence of pivotal life-course transitions with a series of dummy variables indicating whether, over the two-year migration interval, respondents’ primary activity shifted between attending school, working (including being in the military or keeping house), or being idle or inactive (which includes being unemployed, looking for work, laid off, or being disabled). In the “moving out” models, we contrast respondents who transitioned from high school to college (the reference group) with stable college students (in college at both time t and t+2), stable workers (working at both t and t+2), stable idlers (idle at both t and t+2), and transitioners from student to worker, from student or worker to idler, from worker or idler to student, and from idler to worker. Both for theoretical reasons and because few respondents who began a migration interval living independently entered college during the subsequent two years, in the “moving back” models we use stable college students as the reference category.

Critical relationship transitions are captured by a set of dummy variables indicating whether respondents formed, dissolved, or remained in a marital or cohabiting union between the beginning and the end of each migration interval. For both the moving out and moving back models, respondents who remained unpartnered (i.e., neither married nor cohabiting) over the interval serve as the reference category. A separate dummy variable indicates whether, at the beginning of the interval, the respondent or respondent’s partner has a child.

Respondents’ socioeconomic resources are tapped by three variables. Income refers to earnings from work received in the calendar year prior to the interview, measured in thousands of constant 2004 dollars. This and family income (see below) are logged to reduce skewness. Also included as predictors are time-varying dummy variables indicating whether the respondent completed high school (or received a GED) and whether the respondent receives welfare or child support.

Measures of the characteristics of the parental family and household are all taken directly from the parents’ interviews in the main PSID. The time-varying measures are taken from the main PSID interview closest in time to the PSID-TA interview at the beginning of the migration interval. Respondents’ parental family structure, a time-varying covariate, is measured by a set of dummy variables whether the respondent lived with both biological parents, lived with one biological parent and one step-parent, or lived with a biological parent who did not have a resident partner. Parental educational attainment is measure by the years of school completed by the PSID-TA respondent’s mother. Respondents’ parent’s family income, a time-varying covariate, includes all sources of income and is also measured in thousands of constant 2004 dollars (logged). Homeownership is a dummy variable scored 1 if the respondent’s parents own their home. The number of co-resident adult siblings includes all of the respondent’s brothers and sisters age 18 and older who still reside in the parental home. Both of these latter variables are also treated as time-varying covariates.

Our models include several indicators of respondents’ instrumental and emotional connections to their family or origin, as well as indicators of the occurrence of adverse events that could drive young adults out of or back into the parental home. All of these variables are treated as time-varying covariates measured at the beginning of the migration interval. The amount of help respondents receive from their origin family is measured by the number of the following five types of financial assistance received from parents or other relatives over the year preceding the interview: purchasing a house, paying rent or mortgage, buying a car, paying tuition, covering expenses or bills. The extent of respondents’ personal responsibility for their own financial well-being is measured by the mean of the responses to the following four items, each of which is measured on a five-point scale (1 = somebody else does this for me all the time, 5 = I am completely responsible for this all the time): earning your own living, paying rent or mortgage, paying bills, managing your money. Respondents’ emotional attachment to their parents is measured by items asking youth separately how close they feel to their mother (or step-mother) and to their father (or step-father). Possible responses range from 1 (= not close at all) to 7 (= very close). For ease of analysis, we treat these as continuous variables.

Young adults’ decision to leave or return to the parental home may be influenced both by their own health needs and those of their parents. The PSID-TA respondent’s own health is measured by a dummy variable for whether she or he reports being in poor or fair (relative to good, very good, or excellent) health. The indicator of respondents’ parents’ health is measured similarly but is taken directly from the parents’ own reports in the main PSID and refers to either the household head or her/his spouse.

Respondents’ recent experiences of victimization are measured by separate dummy variables indicating whether she or he reports having been a) sexually assaulted or raped or b) beaten or physically attacked (not including sexual assaults). Using information on respondents’ age at the time of these attacks, we develop indicators of whether either victimization occurred in the two years preceding the interview.

To capture time trends in leaving and returning home, our models include dummy variables for the migration intervals beginning in 2007 and 2009, contrasting these with the intervals beginning in 2005. Geographic context is captured by the 10-point Beale-Ross rural-urban classification of counties (1 = completely rural, not adjacent to a metropolitan area; 10 = central counties of metropolitan areas of 1 million or more population) and dummy variables for the four main census regions (Northeast, North Central, South, and West, with Northeast as the reference). Both indicators of geographic context are treated as time-varying covariates, measured at each PSID-TA wave.

Our models control for respondent’s gender and race. Gender is scored 1 for females. Race is a trichotomous variable contrasting whites, blacks, and Hispanics, with whites serving as the reference.

Analytic strategy

To examine the influence of the explanatory variables on the timing at which young adults leave and return to the parental home, we estimate discrete-time event history models (Allison 1984). We segment respondents’ residential histories into a series of two-year migration intervals corresponding to the period between successive interviews. Models are estimated separately for residential spells beginning in and out of the parental home. The 1,068 respondents who were ever observed living in the parental home contribute 1,506 person-periods and the 918 respondents who were ever observed living independently contribute 1,491 person-periods. The dependent variable is a binary variable indicating whether a move out of or back into the parental home occurred during the biennial interval. Once having moved, the respondent is no longer at risk of moving again in that direction, and is no longer observed. Observations are censored at the 2011 interview or, in a few rare cases, at the time of sample attrition. Models are estimated using logistic regression.

Relatively little data are missing; the average amount of missing values across the variables included in the models is only 1.47%. We use multiple imputation to retain cases with missing values (Allison 2001), outputting five datasets to generate parameter estimates for the logistic regression models.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analysis, both for the full sample of person-periods and separately for periods originating in and out of the parental home. Over the typical migration interval, 44% of the respondents initially living with their parents moved out to live independently. Among those initially living independently, 19% returned to the parental home over the subsequent two-year period.

Respondents are on average about 20 years old at the beginning of the interval. Not surprisingly, intervals originating in the parental home were comprised of younger respondents compared to intervals beginning with independent living. A little more than half of the respondents are female. Almost half are white, with blacks and Hispanics (and other races) comprising 40% and 13% of the sample, respectively.

The modal “transition” between primary activities is stably working, that is, being employed at both the beginning and end of the migration interval, which comprises 28% of all migration intervals. Among respondents originating in the parental home, 15% started college over the subsequent biennial period. Among respondents living independently, 23% remained in college over the migration period and 19% transitioned from college student to worker, presumably for many as a result of graduation. Although most respondents were unmarried and not cohabiting at both the beginning and end of the migration interval, this was more common among respondents originating in the parental home than living independently. Almost three times as many of the respondents living independently (20%) than living with parents (7%) were consistently married or cohabiting over the migration interval. About one-fifth of respondents reported having a child.

Turning to the socioeconomic resources, the bulk of respondents have completed high school and few receive welfare or child support. Their average annual income is $4,263 (e1.45 * 1000), though there is substantial variance around this mean.

At the beginning of the typical migration interval, half of respondents’ families included both biological parents, and over one-third included an unmarried biological parent. On average, the respondents’ mothers completed 13 years of schooling. In the year preceding the interval, respondents’ parents’ family income averaged about $56,000. Over two-thirds of these families owned their home. Few parental households contained an adult sibling.

Looking at the indicators of family connectivity, respondents report receiving relatively little financial assistance from their families of origin, although those initially living independently report receiving more than those initially living with their parents. Not surprisingly, then, respondents report high levels of personal responsibility for their day-to-day living, averaging close to 4 on this 5-point scale. On average, respondents report being emotionally closer to their mother than to their father. One-fifth of the respondents’ parents reports that they or their partner is in poor or fair health, but few of the young adults themselves classify their health this way. Six percent of the respondents report being physically victimized in the two years preceding the migration interval and 2% report having been sexually (but not otherwise physically) assaulted.

Because the Transition into Adulthood sampling strategy begins interviewing respondents around when they turn age 18 and then continues to follow them, the number of person-period observations increases over time. The mean of 7.67 on the Beale-Ross rural-urban continuum corresponds roughly to a metropolitan county with a population between 250,000 and 1 million residents. The regional distribution of the sample mirrors the U.S. population reasonably well, with the plurality of respondents living in the South at the beginning of the interval.

Determinants of Moving Out

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariate discrete-time hazards models. (Bivariate models are available as supplemental material.) Model 1 selects residential spells beginning in the parental home and estimates the effects of the independent variables on the risk of moving out. Model 2 selects residential spells beginning outside the parental home and estimates the effects of the covariates on the risk of moving back.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Models of the Timing of Moving Out of and Back into the Parental Home: Transition to Adulthood Study, 2005–2011

| Independent Variable | Moving out

|

Moving back

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | s.e. | eb | b | s.e. | eb | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18 (reference) | ||||||

| 19 | −.18 | .18 | .83 | −.08 | .27 | .92 |

| 20 | −.20 | .19 | .82 | −.39 | .26 | .67 |

| 21 | −.13 | .22 | .88 | −.21 | .29 | .81 |

| 22 | .04 | .25 | 1.04 | −.55† | .29 | .57 |

| 23 | −.02 | .31 | .98 | −1.33*** | .38 | .27 |

| 24 | −.07 | .36 | .93 | −1.46*** | .41 | .23 |

| 25 | −2.03† | 1.12 | .13 | −2.02† | 1.07 | .13 |

| Female | .22† | .12 | 1.25 | −.08 | .15 | .93 |

| Race | ||||||

| White (reference) | ||||||

| Black | .03 | .16 | 1.03 | .18 | .20 | 1.20 |

| Hispanic or other races | .17 | .20 | 1.18 | .45† | .25 | 1.57 |

| Life-course transitions | ||||||

| Primary activity transitions | ||||||

| High school to college (reference) | .69 | .60 | 2.00 | |||

| Stable college student (reference) | −.87*** | .24 | .42 | |||

| Stable working | −1.29*** | .23 | .27 | .60* | .24 | 1.81 |

| Stable idle | −1.48*** | .33 | .23 | 1.35*** | .37 | 3.87 |

| Student to working | −1.37*** | .23 | .26 | .43† | .23 | 1.54 |

| Student/working to idle | −1.11*** | .27 | .33 | .38 | .31 | 1.46 |

| Working/idle to student | −1.31*** | .26 | .27 | .54† | .29 | 1.72 |

| Idle to working | −.90** | .29 | .41 | .60† | .33 | 1.82 |

| Relationship status transitions | ||||||

| Stable non-partnered (reference) | ||||||

| Newly partnered | 1.14*** | .17 | 3.13 | −.31 | .21 | .74 |

| Partnership dissolution | .55 | .33 | 1.73 | −.03 | .28 | .97 |

| Stable partnered | 1.61*** | .26 | 4.98 | −1.27*** | .27 | .28 |

| Parenthood | .37* | .18 | 1.45 | −.06 | .21 | .94 |

| Socioeconomic resources | ||||||

| High school graduation or GED | .13 | .20 | 1.14 | −.36 | .26 | .70 |

| Income | .07 | .06 | 1.08 | .07 | .07 | 1.07 |

| Receiving welfare | −.24 | .27 | .79 | .14 | .40 | 1.15 |

| Parental household and family characteristics | ||||||

| Household structure | ||||||

| Intact family (reference) | ||||||

| Biological and step parent | .13 | .20 | 1.14 | −.61* | .27 | .54 |

| Non-partnered biological parent | −.14 | .16 | .87 | .05 | .20 | 1.05 |

| Mother’s education | .09** | .03 | 1.09 | −.05 | .04 | .95 |

| Family income | .00 | .09 | 1.00 | −.07 | .11 | .94 |

| Homeowner | −.21 | .15 | .81 | .14 | .20 | 1.15 |

| Coresident adult siblings | −.13 | .10 | .88 | .44*** | .12 | 1.56 |

| Family connectivity | ||||||

| Help from family | .18** | .06 | 1.19 | −.00 | .07 | 1.00 |

| Personal responsibility scale | .34*** | .07 | 1.40 | −.18* | .08 | .84 |

| Closeness to mother | −.11* | .05 | .90 | .11† | .06 | 1.11 |

| Closeness to father | −.01 | .03 | .99 | −.01 | .04 | .99 |

| Mother or father in poor health | −.01 | .15 | .99 | .37* | .19 | 1.45 |

| Respondent in poor health | .01 | .21 | 1.01 | −.25 | .28 | .78 |

| Physical victimization | .65* | .26 | 1.91 | −.23 | .30 | .80 |

| Sexual victimization | −.07 | .47 | .93 | 1.47** | .47 | 4.35 |

| Temporal and geographic context | ||||||

| Year of observation | ||||||

| 2005 (reference) | ||||||

| 2007 | −.39* | .16 | .68 | .34 | .22 | 1.40 |

| 2009 | −.47** | .15 | .63 | .65** | .22 | 1.91 |

| Urbanization scale | −.03 | .03 | .97 | .02 | .03 | 1.02 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast (reference) | ||||||

| North Central | .52** | .20 | 1.68 | −.25 | .25 | .78 |

| South | .25 | .19 | 1.28 | −.06 | .23 | .94 |

| West | .32 | .22 | 1.38 | −.19 | .27 | .83 |

| Constant | −1.13 | .73 | .32 | −.78 | .90 | .46 |

| F(44, 475634) | 4.51 | 2.98 | ||||

| N of person-periods | 1,506 | 1,491 | ||||

| N of persons | 1,068 | 918 | ||||

Note:

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

As shown in Model 1, the net hazard of leaving the parental home varies little by age, although respondents who still in the parental home at age 25 are at a borderline level significantly less likely than 18-year olds (the reference group) to move out in the subsequent two years. Also of borderline significance, young women move out of the parental home sooner than young men. The net differences racial differences are statistically non-significant.

With regard to the impact of life-course transitions between primary activities, respondents in all other categories are significantly less likely than respondents entering college from high school to leave the parental home. As indicated by the odds-ratios, the risk of moving out among young adults in each of these categories is less than half the corresponding risk among young adults who transition from high school to college. For the most part, however, differences among the groups not entering college from high school are small. Stable college students and respondents who transition from being idle to working are slightly more likely than the other groups (save high school to college) to move out, but these differences are not statistically significant at conventional levels (significance tests not shown).

Relative to respondents who remain non-partnered (i.e., neither married nor cohabiting) over the interval, young adults who begin or maintain a partnership are significantly more likely to leave the parental home. The net risks of moving out among newly partnered and stably partnered young adults are about three times and five times, respectively, the risk among the stably non-partnered. Young parents are significantly more likely than their childless counterparts to move out of the parental home.

Perhaps surprisingly, none of the coefficients for the three indicators of individual socioeconomic resources—having graduated high school, income, and welfare receipt—is statistically significant. The absence of statistically significant direct effects of these indicators of young adults’ socioeconomic resources on the risk of leaving the parental home may imply that prior theoretical accounts have overemphasized the role of economic independence in creating residential independence.

Only one parental characteristic emerges as a significant net predictor of the timing of home-leaving: respondents’ of more-educated mothers leave home sooner than respondents of less-educated mothers. The net effects of parental family structure, family income, homeownership, and number of co-resident siblings are all statistically non-significant. Here, too, the absence of a statistically significant direct effect of family income on young adults’ risk of moving out of the parental home demonstrates that the nest-leaving process is driven by determinants other than youths’ financial ability to establish an independent residence.

Some of these determinants are listed under the rubric of family connectivity. These results show that young adults are especially likely to leave the parental home not only when they receive financial help from their parents, but also when the young adults themselves report being primarily responsible for their own day-to-day living. These seemingly paradoxical findings could reflect differential effects on the routes to leaving the parental home. Receiving parental help for paying tuition facilitates leaving to enter college, while being able to pay one’s own rent and living expenses facilitates moving to establish other forms of independent living. Self-reported emotional closeness to mother, but not father, inhibits leaving the parental home. Having been physically victimized in the two years preceding the beginning of the migration interval almost doubles the risk of moving out. This positive effect of victimization on moving out is inconsistent with the conjecture that victimized youth may be reluctant to live without potential parental guardians, but it is consistent with the more general literature linking household criminal victimization to subsequent migration (e.g., Dugan 1999).

Consistent with the growth in the percentage of young adults remaining in the parental home, the coefficients for the year-of-observation dummy variables reveal a monotonic decline between 2005 and 2011 in the risk of leaving the parental home. Worth noting, however, is that these trends remain significant even when the other covariates are controlled, and thus trends in respondents’ life course transitions and economic resources cannot explain the apparent decline in the rate at which young adults leave the parental home.

Model 1 of Table 2 also provides some suggestive evidence that young adults’ decision to move out responds to the cost of establishing an independent household. The risk of leaving the parental home is significantly higher in the North Central region, where housing costs are comparatively low, than in the Northeast, where costs are high. Together with the net time trend, our results suggest that unobserved characteristics of both the temporal and geographic context drive young adults’ desire and/or ability to leave the parental home.

Determinants of Moving Back Home

Model 2 of Table 2 presents the results of a largely parallel analysis of the timing of young adults’ returning to the parental home, conditional upon having moved out. The coefficients for age show a near-monotonic decline in the odds of moving back home. The sex difference in the risk of returning home is small and statistically non-significant. Net of the other covariates, young black adults do not differ significantly from their white counterparts, but at a borderline significance level Hispanics are more likely than whites to move back home.

With regard to the impact of primary activity transitions, young adults in most other activity categories are significantly more likely than stable college students (the reference category) to move back to the parental home. Only those making the transition from high school to college (a very small group) and those who transition from student to working or idle do not differ significantly at even a borderline level from stable college students. Young adults who are consistently idle are especially likely to return home. But worth noting is that even a transition from student to worker—indicating in most instances getting a job after graduating from college—increases the risk of moving back home relative to remaining in college (albeit the difference is significant at only a borderline level). Thus, it appears that even ostensibly successful life-course transitions can precipitate a move back home. Perhaps in recessionary times young graduates’ jobs are insufficiently remunerative to allow them to maintain an independent household.

Of the relationship status transitions, being consistently partnered is associated with a substantial and significant reduction in the risk of returning home, relative to being stably non-partnered. Moreover, comparing the coefficients for stably partnered with partnership dissolution shows that young adults who dissolve a romantic partnership over the interval are significantly more likely than those who remain partnered to move back to the parental home (in a model using stable partnered as the reference, p < .000). In contrast, young adults who begin a romantic partnership over the interval do not differ significantly from those who remain unpartnered in their risk of returning home, although the difference is in the anticipated direction and fairly large. Parenthood is not significantly associated with the odds of moving back to the parental home.

Similar to the findings for leaving home (Model 1), the coefficients for the indicators of individual socioeconomic resources are all non-significant. The effects of economic independence on young adults’ risk of returning are either weak or mediated by the other covariates.

Two of the parental household and family characteristics exert a significant direct effect on young adults’ risk of moving back home. Young adults are significantly less likely to move back home if their current family-of-origin includes a stepparent, and they are significantly more likely to return home if their parents’ household includes adult siblings.

Although receiving financial help from family does not appear to influence young adults’ decision to move back home, those who report taking greater responsibility for their own financial management are significantly less likely than others to return. Mirroring the corresponding difference in the risk of leaving the parental home, reported emotional closeness to one’s mother (albeit not one’s father) is significantly (at a borderline level) and positively associated with the odds of returning to the parental home. Young adults whose parents report being in relatively poor health are significantly more likely than other youth to move back home. Having recently been sexually victimized is strongly and significantly associated with the risk of moving back home. Although few respondents report having been sexually assaulted in the two years preceding the beginning of the migration interval (Table 1), those who were exhibit a net risk of returning to the parental home over four times those who were not.

Consistent with expectations, the coefficients for year of observation reveal a monotonic increase in the risk of moving back home, although only one of the contrasts is significant. The risk of returning between 2009 and 2011 is about 90% greater than the risk between 2005 and 2007. The risk of moving back home does not vary significantly by either the level of urbanization of the county of residence or across geographic regions of the country.

Effect Sizes

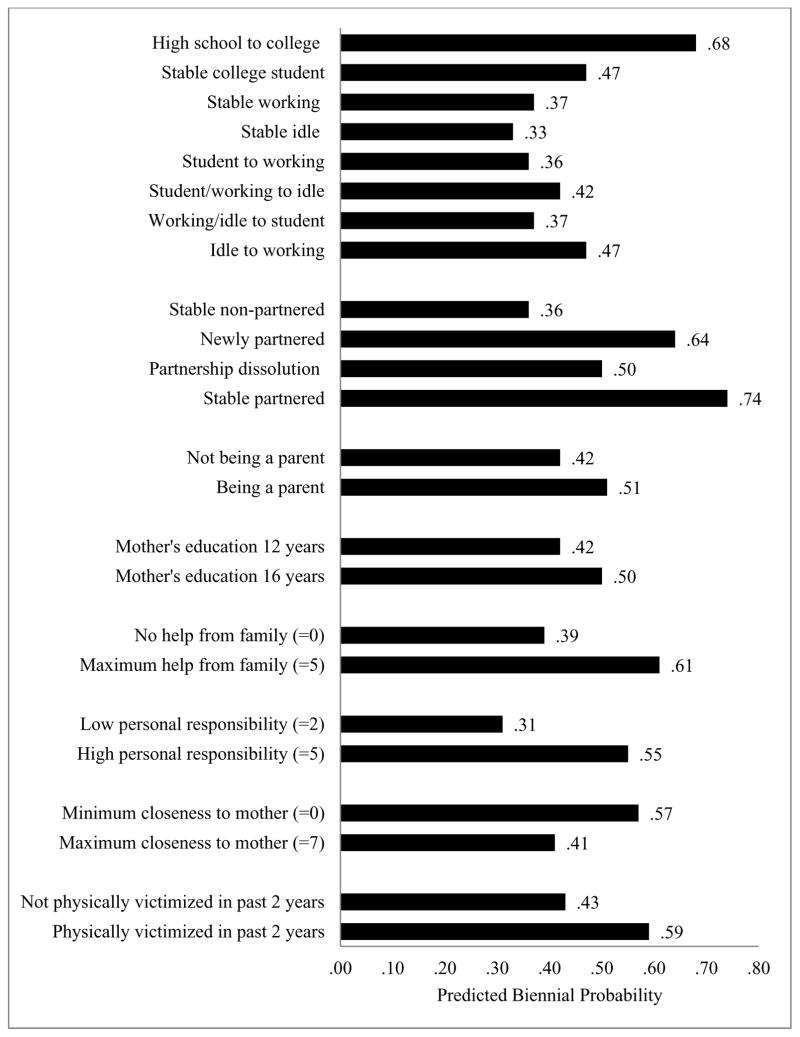

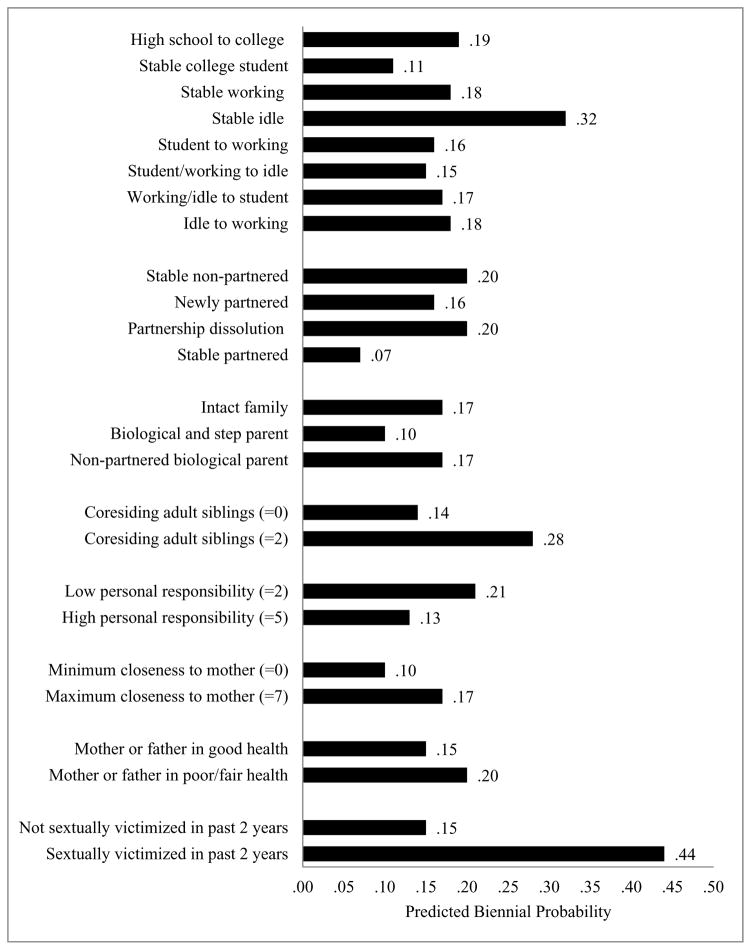

To better illustrate the magnitude of the associations between the independent variables and the risks of leaving and returning to the parental home, Figures 1 and 2 display predicted biennial probabilities of moving out of and back to the parental home for the values of selected covariates. These probabilities are generated using the coefficients from the multivariate models in Tables 2 and 3, setting all other covariates at their respective sample-specific means.

Figure 1.

Predicted Biennial Probabilities of Moving Out of the Parental Home, by Selected Characteristics: Transition into Adulthood Study, 2005–2011

Figure 2.

Predicted Biennial Probabilities of Moving Back into the Parental Home, by Selected Characteristics: Transition into Adulthood Study, 2005–2011

Figure 1 presents the predicted biennial probabilities of leaving home. In general, these probabilities suggest that the independent variables bear substantively (as well as statistically) significant associations with the risk of leaving home. For example, the probability of leaving home for youth transitioning from high school to college is more than double that of youth who remain idle. And, youth who initiate a marital or cohabiting relationship are almost twice as likely as those who remain unpartnered to leave home.

Respondents whose mother completed 16 years of schooling are eight percentage points more likely to leave home over a two-year period than respondents whose mother completed only 12 years of schooling. Having been physically assaulted during the two years preceding the migration interval increases the probability of moving by 16 percentage points.

Figure 2 presents the analogous probabilities of moving back to the parental home. For the most part, the independent variables bear weaker associations with the risk of moving back than the risk of moving out, at least when assessed in absolute terms. One important exception is the association between being sexually victimized and the probability of returning home, with victims 29 percentage points more likely to return. The magnitudes of the associations involving the number of siblings residing in the parental home and respondents’ emotional closeness to their mother are also reasonably large.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The young adult years are a demographically dense period of the life course, characterized by transitions into and often out of marriage and cohabitation, and by frequent residential moves (Rindfuss 1991). One particularly critical form of residential mobility is movement out of and back into the parental home. Yet, despite a pronounced delay over recent decades in the age at which young adults leave home, and a parallel increase in the probability that they move back, we know relatively little about contemporary determinants of the timing of young adults’ leaving and returning to the parental home. We explore this issue here by using recent longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Transition into Adulthood study, which has collected information from a nationally-representative sample of young adults ages 18 to 26 between 2005 and 2011. In addition to its timeliness, our analysis goes beyond most prior studies of the determinants of leaving and returning to the home by incorporating a much wider array of explanatory variables, by taking measures of the focal concepts from both the young adults and their parents, and by conducting parallel analyses of both moving out of and moving back into the parental home. Our analyses lead to three broad conclusions.

First, a broad array of characteristics, statuses, and events shape young adults’ decision to leave and/or return to the parental home. Consistent with the life course perspective’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of critical events, entering college and forming a romantic union encourage home-leaving, while graduating from college and dissolving a partnership precipitate moving back. Consistent with the life course principle of linked lives, youth who report being emotionally close to their mothers are less likely to leave home and more likely to return, and young adults who receive greater instrumental support from their parents leave home earlier than other youth. Young adults are less likely to move out of and more likely to return to households that contain other adult siblings, and they are more likely to return to households when a parent is in poor health. Broadly consistent with the life course principle of inter-individual heterogeneity, the presumably random event of a physical or sexual victimization increases the risk of leaving the parental household and increases the risk of moving back. And consistent with the life course perspective’s emphasis on the importance of socio-historical context, we observe a downward trend in leaving home, an upward trend in returning, and regional differences in home-leaving.

These results suggest that a comprehensive explanation for why and when young adults leave or return to the parental home must go beyond a simplistic focus on coincident life-course transitions and the financial wherewithal to establish and maintain an independent household. In particular, youths’ instrumental and emotional connections to the family of origin must also be considered. At the same time, the apparently diverse array of mobility-related motivations, opportunities, and constraints reflected in our results is likely to confound attempts to develop a unified and cohesive theory of home-leaving and home-returning.

A second conclusion to be drawn from our analysis is that the factors that drive young adults out of the parental home are not always the same as the factors that drive them back. This conclusion is broadly consistent with that of older studies that considered a smaller number of covariates (e.g., Goldscheider et al. 1999). To be sure, we do observe some symmetry in the determinants of moving out and back. For example, being in a romantic partnership and the assumption of personal financial responsibility hasten home-leaving and deter home-returning, and emotional closeness to one’s mother prolongs home-leaving and encourages home-returning. But some other factors influence only the risk of moving in one direction. For example, parenthood and receiving financial help from family appear to increase the risk of moving out but have no bearing on the risk of moving back. Having a parent in poor physical health and being the victim of a sexual assault increase the risk of moving back but do not appear to influence the risk of moving out. Theories of moving out and theories of moving back, therefore, may need to give different weight to the factors that propel these moves.

Third, it does not appear that recent trends in either the timing of leaving home or in the risk of moving back can be easily explained by trends in young adults’ likelihood of experiencing various employment or relationship transitions, their socioeconomic status, or the other measured covariates. As hypothesized, we find that during and immediately after the Great Recession of 2007–2009 young adults delayed their home-leaving and experienced an increased risk of moving back home. These trends are consistent with the hypothesis that the economic adversity engendered by the Great Recession impeded young adults’ ability to both establish and maintain an independent household. Yet, the fact that we observe these trends even after controlling for trends in some individual-level hardships—for example, fewer transitions to employment, marriage, and college, and lower incomes—may imply that secular trends in the timing of home-leaving and home-returning stem as much from changing attitudes and norms regarding the desirability and attractiveness of living in the parental home as from trends in young adults’ ability to establish and maintain an independent household. The life course approach directs attention to norms regarding the appropriate age at which various transitions should occur (Neugarten et al. 1965; Settersten and Hagestad 1996); these norms are particularly germane to the timing of home-leaving (Billari and Liefbroer 2007). Increases in the age at home-leaving even net of other changes could reflect changing ideals and expectations about when it is most appropriate for young adults to vacate the parental nest. Changing norms regarding the desirability of parental coresidence may also drive young adults’ apparently increasing willingness to move back home after living independently. Admittedly, our analysis covers only a short time span, and given the PSID-TA sampling strategy, it is difficult to separate period effects from age effects. And there may be other ramifications of recent economic changes, including a depressed housing market and rising student loan debt, whose effects are not captured by the individual-level covariates. But future research may profit from exploring more directly the sources of change, including changing age norms, in the timing at which young adults leave and return to the parental home.

Future research might consider other avenues of investigation as well. The influence of various personal and family-of-origin characteristics may vary by the particular pathway through which young adults leave home (e.g., Buck and Scott 1993). A given facilitator may influence the risk of leaving home to attend college differently than, say, to live with a romantic partner (Goldscheider and Da Vanzo 1989). Our analysis incorporates the various routes to leaving home as explanatory variables, thus enabling largely parallel analyses of both leaving and returning home. But our understanding of home-leaving may be enhanced by considering the various pathways to leaving home as competing routes, perhaps differentially affected by individual attributes and characteristics of the parental home.

One of the novel findings of our study is that experiencing a physical or sexual victimization hastens both home-leaving and home-returning. Future research might explore in greater detail the types of victimization that precipitate these residential moves. For example, the impact of victimization might differ by the victim’s relationship to the offender (e.g., stranger versus family member) and by the place of victimization (e.g., home, school, workplace). Drawing on the life course perspective, our theoretical framework considered victimization experiences to be adverse events that could deflect otherwise normative life course trajectories. Future research might attempt to identify other such unexpected life course shocks.

Cross-national comparisons of the determinants of leaving and returning home may help identify similarities and contextual variation in these life course transitions. Our findings suggest that for the most part the drivers of leaving home operate similarly in the U.S. as in Germany and The Netherlands (Mulder et al. 2002) and that youths’ emotional closeness to their parents inhibits home-leaving in the U.S. as it does in Canada (Mitchell et al. 2004). We find weaker net effects of family structure on home-leaving than one study of The Netherlands (Blaauboer and Mulder 2010), perhaps suggesting that nontraditional family forms are more institutionalized in the U.S. With regard to returning home, we note that both our study and Stone et al.’s (2014) analysis of British data find that moving back after leaving full-time education is a common occurrence and that relationship dissolution frequently precipitates a move back. However, while our study finds that parenthood is not significantly related to the risk of returning home, Stone et al. (2014) find that mothers whose partnership recently dissolved experience relatively low rates of moving back, which they note is a likely consequence of Britain’s social housing policy that enables unmarried mothers to live independently.

Future research might also explore variations in the determinants of home-leaving and home-returning by gender, race, and age. For example, the dissolution of a marital or cohabiting union, particularly one that includes children, may influence the moving decisions of young women—the more likely custodial parents—differently than young men (Stone et al. 2014). Upon the dissolution of a union, young mothers may be particularly likely to move back in with their parents in order to receive help with child-rearing. More generally, young women’s decisions to leave or return to the parental home may be more strongly influenced than young men’s decisions by noneconomic considerations, such as emotional closeness to parents, parents’ physical and financial needs, and other family background characteristics (Blaauboer and Mulder 2010). Similarly, noneconomic factors may be more important for racial and ethnic minorities than for whites, with the former’s decisions grounded more in culturally-based preferences and the latter’s deriving more from economic exigencies (Britton 2013). And, the salient determinants of leaving and returning home might vary by young adults’ age. The presumably greater desire of older young adults to live independently may render their residential mobility decision-making comparatively unresponsive to the factors that facilitate or impede home-leaving and home-returning among adolescents and youth in their early twenties. Continued monitoring of the patterns and determinants of leaving and returning to the parental home is needed to understand fully this critical stage of the life course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant to the first author from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03 HD078316). The Center for Social and Demographic Analysis of the University at Albany provided technical and administrative support for this research through a grant from NICHD (R24 HD044943). We thank Katherine Trent and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Contributor Information

Scott J. South, Department of Sociology, Center for Social and Demographic Analysis, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, NY 12222, Phone: 518-442-4691, Fax: 518-442-4936

Lei Lei, Department of Sociology, Center for Social and Demographic Analysis, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, NY 12222, Fax: 518-442-4936.

References

- Allison Paul D. Event History Analysis: Regression for Longitudinal Event Data. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Allison Paul D. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett Jeffrey Jensen. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Avery Roger, Goldscheider Frances, Speare Alden., Jr Feathered Nest/Gilded Cage: Parental Income and Leaving Home in the Transition to Adulthood. Demography. 1992;29:375–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billari Francesco C, Liefbroer Aart C. Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Impact of Age Norms on Leaving Home. Demography. 2007;44:181–198. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaauboer Marjolein, Mulder Clara H. Gender Differences in the Impact of Family Background on Leaving the Parental Home. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. 2010;25:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Britton Marcus L. Race/Ethnicity, Attitudes, and Living with Parents during Young Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75:995–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Buck Nicholas, Scott Jacqueline. She’s Leaving Home: But Why? An Analysis of Young People Leaving the Parental Home. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:863–74. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen John S. Adolescent Competence and the Shaping of the Life Course. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96:805–842. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder Kyle, Pais Jeremy, South Scott J. Neighborhood Diversity, Metropolitan Constraints, and Household Migration. American Sociological Review. 2012;77:325–53. doi: 10.1177/0003122412441791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Vanzo Julie, Goldscheider Frances Kobrin. Coming Home Again: Returns to the Parental Home of Young Adults. Population Studies. 1990;44:241–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan Laura. The Effect of Criminal Victimization on a Household’s Moving Decision. Criminology. 1999;37:903–930. [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen H, Jr, Johnson Monica Kirkpatrick, Crosnoe Robert. The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In: Mortimer Jeylan T, Shanahan Michael J., editors. Handbook of the Life Course. Springer; 2003. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch John. Prices, Parents, and Young People’s Household Formation. Journal of Urban Economics. 1999;45:47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F., Jr On a New Schedule: Transitions to Adulthood and Family Change. The Future of Children. 2010;20:67–87. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F, Jr, Rumbaut Ruben G, Settersen Richard A., Jr . On the Frontier of Adulthood: Emerging Themes and New Directions. In: Settersen Richard A, Jr, Furstenberg Frank F, Jr, Rumbaut Ruben G., editors. On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Giele Janet Z, Elder Glen H., Jr . Life Course Research: Development of a Field. In: Giele Janet Z, Elder Glen H., Jr, editors. Life Course Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld Jenny, Liefbroer Aart C, Beekink Erik. The Effect of Parental Resources on Patterns of Leaving Home among Young Adults in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review. 1991;7:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances. Recent Changes in Us Young Adult Living Arrangements in Comparative Perspective. Journal of Family Issues. 1997;18:708–724. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances. Parenthood and Leaving Home in Young Adulthood. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; Washington, DC. March 31–April 2.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Goldscheider Calvin. Leaving and Returning Home in 20th Century America. Population Bulletin. 1994:4. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances K, Goldscheider Calvin. The Effects of Childhood Family Structure on Leaving and Returning Home. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:745–756. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Goldscheider Calvin. The Changing Transition to Adulthood: Leaving and Returning Home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Goldscheider Calvin, St Clair Patricia, Hodges James. Changes in Returning Home in the United States, 1925–1985. Social Forces. 1999;78:695–720. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Da Vanzo Julie. Living Arrangements and the Transition to Adulthood. Demography. 1985;22:545–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Da Vanzo Julie. Semiautonomy and Leaving Home in Early Adulthood. Social Forces. 1986;65:187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Da Vanzo Julie. Pathways to Independent Living in Early Adulthood: Marriage, Semiautonomy, and Premarital Residential Independence. Demography. 1989;26:597–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances K, Hofferth Sandra L, Curtin Sally C. Parenthood and Leaving Home in Young Adulthood. Population Research and Policy Review. 2014;33:771–796. doi: 10.1007/s11113-014-9334-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Thornton Arland, Young-DeMarco Linda. A Portrait of the Nest-Leaving Process in Early Adulthood. Demography. 1993;30:683–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Mary Elizabeth. Home Economics: Metropolitan Labor and Housing Markets and Domestic Arrangements in Young Adulthood. Social Forces. 2003;81:1399–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan Greg. Moving Back Home: Insurance against Labor Market Risk. Journal of Political Economy. 2012;120:446–512. [Google Scholar]

- Mather Mark. [Accessed November 5, 2012];In U.S., a Sharp Increase in Young Men Living at Home. 2011 http://www.prb.org/Articles/2011/us-young-adults-living-at-home.asp.

- Mayer Karl Ulrich. New Directions in Life Course Research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2009;35:413–433. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Barbara A. Family Structure and Leaving the Nest: A Social Resource Perspective. Sociological Perspectives. 1994;37:651–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Barbara A. Life Course Theory. In: Ponzetti James J., Jr, editor. International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family. 2. New York: Macmillan; 2003. pp. 1051–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Barbara A, Wister Andre, Gee Ellen Margaret Thomas. The Ethnic and Family Nexus of Homeleaving and Returning among Canadian Young Adults. Canadian Journal of Sociology. 2004;29:543–575. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder Clara H, Clark William AV. Leaving Home for College and Gaining Independence. Environment and Planning A. 2002;34:981–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder Clara H, Clark William AV, Wagner Michael. A Comparative Analysis of Leaving Home in the United States, The Netherlands and West Germany. Demographic Research. 2002;7:565–92. [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten Bernice L, Moore Joan W, Lowe John C. Age Norms, Age Constraints, and Adult Socialization. American Journal of Sociology. 1965;70:710–717. doi: 10.1086/223965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman Katherine S. The Accordion Family: Boomerang Kids, Anxious Parents, and the Private Toll of Global Competition. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics. The Child Development Supplement Transition into Adulthood Study 2009 User Guide. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Payne Krista K. On the Road to Adulthood: Leaving the Parental Home. National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2011. (FP-11-02) Retrieved from http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profies/file98800.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Payne Krista K. Young Adults in the Parental Home, 1940–2010. National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2012. (FP-12-22) Retrieved from http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profies/file122548.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Payne Krista K, Copp Jennifer. Young Adults in the Parental Home and the Great Recession. National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2013. (FP-13-07) Retrieved from http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profies/file126564.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Putney Norella M, Bengston Vern L. Intergenerational Relations in Changing Times. In: Mortimer Jeylan T, Shanahan Michael J., editors. Handbook of the Life Course. Springer; 2003. pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]