Abstract

Currently, China has a growing need for rehabilitative care; however, rehabilitative care has been underdeveloped for decades. Since the end of 2010, pilot programs in 46 cities (districts) of 14 provinces have been initiated by the Ministry of Health in China to establish formal arrangements for facilitating the delivery of continuous medical rehabilitative care for local communities. After 2 years of pilot work, an evaluation was conducted by researchers. This paper reviews the current status of rehabilitative care in China and discusses the findings of the nationwide pilot program on the integrated rehabilitative service. Some key mechanisms and main issues were identified after analyzing the preliminary outcomes of some of the pilot programs.

Keywords: Pilot, Medical rehabilitation

Introduction

The health reform plan in 2009 stressed the development of a health service delivery system with more integration between preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative care.1 With political commitment in developing and improving rehabilitative care delivery, the Ministry of Health (MoH) in China has launched a pilot program on rehabilitative care delivery in 46 cities (districts) in 14 provinces covering the western, central, and eastern regions in the country since August 2010. Selection of the pilot programs was based on the progress of the public hospital reforms in general, since the reconstruction of rehabilitative care has been viewed as an important means to set up an orderly case management system between public hospitals at different levels and attend more patients in lower-level health institutions.

Fourteen provinces were selected to launch their own local programs in 46 cities (districts), to improve the rehabilitative service delivery through innovative mechanisms to better cater to the local population's rehabilitative needs. The pilot cities (districts) were selected by their provincial health bureaus based on their local commitments in public hospital reforms and overall capability of rehabilitative care delivery.

To identify issues and challenges of the nationwide pilot programs and summarize lessons and experience from the locals, the MoH has commissioned a group of researchers in a national health policy think tank to design and implement an independent evaluation project at the beginning of the nationwide pilot program. This paper reports the main findings of the researchers and discusses the main mechanisms employed by the local pilots.

Rehabilitative service in China

China has over 85 million disabled people, of whom 90% have rehabilitative needs; however, only a little over 10 million can access rehabilitative care. Meanwhile, there are 270 million people with chronic diseases, among whom 130 million have an urgent need for rehabilitation.2, 3 For example, among patients with stroke, 70–80% experienced functional problems (motion, sensory, linguistic, swallowing, and cognitive problems).4 These needs have increased the disease burdens of families and societies.

In the aging population, the number of those over 60 years old has reached 222 million, which is about 16.1% of the total population5; this number will increase up to 255 million by 2020.6 Studies show that nearly half of the people with geriatric diseases are in need of medical rehabilitation. Rehabilitative demands have increased steadily with rising financial protections for health. A survey on 180 patients with cerebrovascular events in Guangwai District of Beijing showed that 71.71% hoped to receive home care, 34.21% required community-based rehabilitative care, and 34.21% wanted access to mental counseling.2

Modern rehabilitative medicine although was formally established in China in the early 1980s, it has experienced slow development. Owing to the marginalized status among all clinical units, rehabilitative medicine has been regarded as less important. In China, rehabilitation has the same connotation as recovery. Therefore, culturally speaking, the Chinese always treat rehabilitation as a natural outcome of diseases, rather than an active handling of dysfunctional issues of the body. Since its establishment in China, rehabilitative medicine has not been clearly defined; it was used in combination with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). At the beginning, rehabilitative medicine mainly involved physiotherapy and TCM; its focus was then shifted to cover resort care. Finally, the definition of disability from International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) has been gradually adopted, and a medical model emerged as a result of the health providers' attention to the patients' quality of life.

According to the National Survey on Resources of Rehabilitative Medicine in 2009, rehabilitative medicine units were found in 3288 general hospitals and 338 stand-alone rehabilitation centers. In total, there were 52,047 beds and 39,833 rehabilitative staff (15,949 rehabilitative specialists, 13,747 therapists, and 10,137 nurses). Properly licensed rehabilitative doctors only accounted for 38.46%. There was a personnel gap of 15,000 rehabilitative specialists and 28,000 therapists based on the requirements of personnel quota listed in the Guide on Establishing and Managing Rehabilitative Units in General Hospitals.7

Data revealed that the rehabilitative staff had low education and professional titles. Only 50% of doctors, 34% of therapists, and 30% of nurses obtained medium or higher titles; 50% of doctors, 33% of therapists, and nearly 15% of nurses were with bachelor or higher-degree diplomas.7

The overall resources of rehabilitative medicine are in severe shortage and are unevenly distributed between rural and urban areas and among different regions. The quality resources are mainly concentrated in large medical centers in big cities, while there is a relatively weak capacity in health facilities in medium- or small-sized cities and very poor competence in grassroots health centers and clinics in rural areas. Conflicts between provision and demand for rehabilitation are prominent.7, 8

First, a three-tier rehabilitative network led by rehabilitative units in tertiary hospitals and supported by secondary general hospitals/stand-alone rehabilitative centers and community health facilities has not been fully established. A large number of patients had prolonged stays in tertiary and secondary hospitals and were unwilling to be referred to primary health facilities. Two-way referral programs are not formed between health facilities.7, 8

Second, there are gaps between rehabilitative capacity and demand. Although the need for acute rehabilitative care is increasing, most rehabilitative units are only capable of providing post-acute rehabilitative care. Data showed that 20% of provincial rehabilitative units, 30% of municipal level facilities, and 56% of below-city level facilities were unable to provide acute rehabilitation.7, 8

Third, rehabilitative care is confined only in clinical settings, not extending to homes, communities, and other social settings. Owing to the lack of sound management of rehabilitative care, patients cannot access timely, affordable, and quality rehabilitative care.

In China, the provision of rehabilitative services has been mainly decentralized to provinces and municipalities. Further, several ministries besides those in health sectors have been involved in the rehabilitation provision. The Disabled People's Federation (DPF) is responsible for providing care for the disabled people. The National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) is in charge of healthcare service provision, including rehabilitative care. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) is financing rehabilitative care for the work-related injury. The Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCF) is responsible for subsidizing elderly rehabilitative care.

To meet the increasing demand for rehabilitative care, the Chinese government has identified rehabilitative care delivery as the main component of the health system reform since 2009 and defined the requirements for developing rehabilitative care in the 12th Five-Year Plan for Health Development. All these have provided the local health authorities with ideas and prompts for designing their local programs.

Meanwhile, the national health authority has initiated pilot programs in 46 cities (districts) of 14 provinces, while coordinating with the DPF and other ministries, to generate lessons and experience that can be scaled up nationwide.

Early in 2012, the MoH issued a Guidance on Rehabilitative Medicine during the 12th Five-Year Plan period, which proposes to establish tiered and staged rehabilitative service networks and to build a two-way referral system between general hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and community health facilities.

The policy detail specifications for the service network included the following: (1) enhanced development and management of rehabilitative service, (2) developed rehabilitative professionals, (3) increased capacity to deliver rehabilitative service, (4) establishment of tiered and staged rehabilitative care, and (5) pooled and coordinated use of rehabilitative resources. The document has provided a blueprint for the development of health rehabilitative care during the 12th Five-Year Plan period, giving a policy framework for local programs.

Early in 2013, the DPF and MoH jointly launched the Notice on Facilitating Cooperation between the Disabled Rehabilitation Facilities and Medical Rehabilitation Facilities, which aimed to promote the integration of disabled rehabilitative services and medical rehabilitative services.

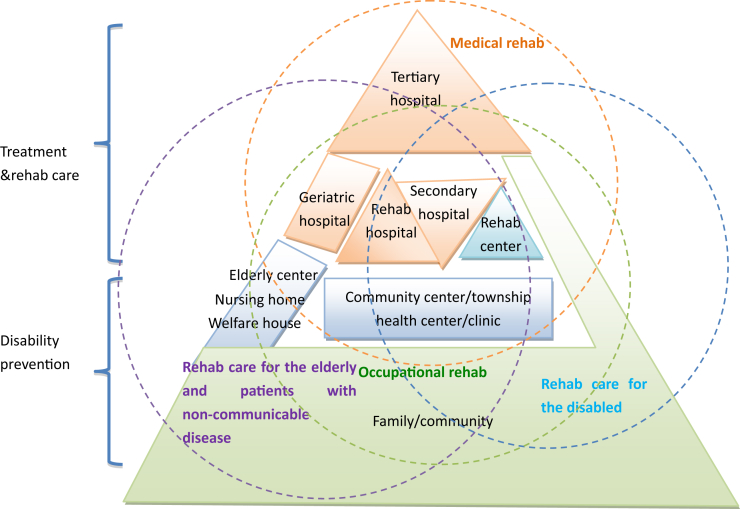

Fig. 1 illustrates the framework of the rehabilitative service network in China. The medical rehabilitative service network is composed of four interconnected parts, namely, clinical rehabilitation, occupational rehabilitation, disabled rehabilitation, and rehabilitation of patients with long-term conditions and elderly care needs. Clinical rehabilitation serves as the central part of the entire service network. For patients with various rehabilitative needs, such as those with workplace injuries, long-term conditions, and geriatric diseases, and for those with disability and are handicapped, different sub-networks of services have been developed. These service networks overlap to allow communication between the community and households to provide preventive care for disabilities and count on the three-tier clinical facilities in diagnosing and treating patients with various medical rehabilitative needs.

Fig. 1.

Current rehabilitative care delivery system in China.

Pilots of integrated rehabilitative care delivery in 14 provinces

Since 2011, 46 cities (districts) in 14 provinces have launched pilot programs of medical rehabilitative care to explore ways of identifying the roles and responsibilities of different institutions and facilitating collaboration between them, and to integrate resources and streamline services for various demanders of rehabilitative care with a view to optimizing the utilization of regional rehabilitative resources, reducing disease burdens, and improving the patients' functionality and quality of life.

Based on the monitoring and evaluation conducted by the China National Health Development Research Center, a few local pilot programs showed improved cost-effectiveness, enhanced hospital performance, increased efficiency, lowered disease burden, and increased satisfaction of the patients. As shown by the investigation results, the patients' economic disease burden has been decreased and satisfaction enhanced after the program implementation.

For example, the Rehabilitation Unit of Shanghai Huashan Hospital actively launched a program of early rehabilitative intervention and built a referral system with Yonghe Hospital. By transferring stable patients with acute cerebral infarction to the secondary hospital, Huashan Hospital observed not only reduced cost per episode but also lowered cost per health gain (Table 1). This has played an active role in reducing the overall disease burden of the patients.

Table 1.

Cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation in the pilot and control hospitals in Shanghai.

| Hospitals | Per capita rehabilitation costs (Yuan) | Per day cost (Yuan) | ADL increase (score) | Cost per ADL (Yuan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | ||||

| Huashan | 921.14 | 71.52 | 12.09 | 76.19 |

| Yonghe | 6501.71 | 165.30 | 9.60 | 677.17 |

| Control | ||||

| Dongfang | 1903.75 | 103.46 | 11.02 | 172.79 |

| Yangzhi | 19,598.70 | 349.39 | 3.50 | 5593.08 |

ADL: activities of daily living.

Each pilot site has a strengthened quality control and referral mechanism and standardized providers' behaviors. Although this has increased the overall health expenditures over a short period, the overall social costs have been reduced owing to the rapid improvements and more health gains per unit cost. Therefore, the financial burden of the patients and their families has been greatly lessened with lesser out-of-pocket (OOP) payments.

Drug share of the total revenue of the hospitals decreased in all pilot institutions, which reduced the OOP payments of the patients. The average percentage of drug cost of the total revenue was 29.39% among all seven secondary pilot hospitals,9 while the national average was 41.1%.10 The share of the OOP expenditure has decreased in some pilot hospitals, showing the burden-relieving effect of the pilot programs.

The patients' satisfaction has been enhanced owing to the improved care quality based on the analysis of 542 patients' survey results. The patients had the highest satisfaction with the skills of the health professionals and their explanation of the cases, followed by that with the equipment and referral procedures. The patients were less satisfied with the prices and foods provided by the hospitals and least satisfied with the reimbursement level.9

The evaluation results revealed that the pilot areas have taken a general approach featuring multi-agency collaboration and integrated care of community rehabilitation, disability rehabilitation, and elderly care. They actively gained policy, financial, and other supports from related agencies.9 The Zibo Bureau of Health in Shandong Province has worked with other government agencies in designing and planning for the rehabilitative care network. With resources from the civil affairs and the DPF and favorable reimbursement policies from health insurance agencies, the local program has developed a medical rehabilitative care system among health facilities. Meanwhile, the Zibo Bureau of Health has also organized various types of promotion and advocacy activities on rehabilitation, with the help of the media and health facilities. All these contribute to a smooth accommodation of rehabilitation in social care networks. The Beijing Bureau of Health actively communicated with finance and social security agencies, explored clinical standards and provider payment reforms, and emphasized the importance of collaboration with the DPF on the training of community health workers and disability rehabilitation. The Shanghai Bureau of Health and other relevant government agencies jointly issued out Guidance on Encouraging Transformation of Business Operation of Secondary Hospitals in Shanghai (Pilot Policy) in 2012, which has guided the poorly performing secondary hospitals to transform their business model by providing policy supports for payment, reimbursement, and personnel reforms at an institutional level. To date, two to three secondary hospitals in Shanghai have successfully transformed their operational model by shifting their clinical focus to rehabilitation.

As found out through focal group discussions, all local programs have benefitted from the multi-agencies' policy support, institutional management mechanisms, and technical backup of tertiary hospitals. Generally, joint efforts of these aspects contributed to the successful implementation of the local programs. Here are some main mechanisms employed by the pilots in implementing the programs.

Decision-making mechanisms

Rehabilitation-related agencies include health bureaus, the DPF, social security bureaus, civil affairs bureaus, pricing departments, financial bureaus, and staffing bureaus. Different agencies are in charge of the different parts of rehabilitative care. For instance, health authorities, the DPF, and civil affairs agencies are in charge of rehabilitative medicine, disability rehabilitation, and community rehabilitation for patients with non-communicable diseases (NCDs), occupational rehabilitation, and elderly care. Social security agencies are responsible for the reimbursements and payments and pricing agencies for medical fee schedules. The pattern and development of a local rehabilitation system totally depend on the collaboration and commitment of these relevant agencies. Local health authorities all placed rehabilitation reforms under the umbrella policy framework provided by the 12th Five-Year Plan and health reform (especially public hospital reform), defined health resource allocation and management measures, designed mechanisms concerning quality control and referral, defined roles and responsibilities of institutions at various levels, and strengthened professional training and management.

Managerial mechanisms

To encourage early intervention of rehabilitative professionals in delivering acute care, most health facilities designed incentives for promoting consultation of rehabilitation professionals, including direct consultation without appointments, double counting of rehabilitation revenue, and proportional commission for clinical units referring rehabilitation patients to rehabilitation units. All these measures played an important role in promoting early rehabilitative interventions in pilot hospitals. Huashan Hospital in Shanghai even innovatively removed beds in its Rehabilitation Unit and required rehabilitation doctors and therapists to go to the bedside of the patients. The Rehabilitation Unit of Huashan Hospital observed a good performance.

Institutions at various levels developed partnerships, such as service outsourcing and trusteeship, to promote collaboration and development of referral schemes, define roles and responsibilities, and build mutual trust. For instance, People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and Shanghai Huashan Hospital developed trusteeship with secondary hospitals to implement two-way referral mechanisms under a uniform administrative scheme. Haiyuan Hospital of Heilongjiang Province and the No. 1 Teaching Hospital of Harbin Medical University signed contracts and regulated technical, managerial, and business collaborations.

Technical capacity building

From a technical perspective, the successful pilot programs usually had at least one regional center of medical excellence which can meet the demand for complex and difficult rehabilitation cases, with strong capacity in delivering early rehabilitative interventions, assuring regional quality, providing personnel training and technical guidance, and assisting health authorities in launching clinical management and capacity-building activities. Secondary hospitals or rehabilitation hospitals need to have competency in handling post-acute patients and meeting their rehabilitative demands. Meanwhile, community health facilities shall be adequately equipped to handle responsibilities in the bottom of the service network and continue rehabilitative services.

Key issues identified by the pilots

Some key issues were defined and reported by the researchers after in-depth interviews and focal group discussions with key stakeholders of the local pilots.

Underdeveloped social rehabilitation network

Through discussions with local policy makers, investigators found that many government agencies, especially the DPF and civil affairs bureaus, strongly advocate for building a social care network, which will focus on medical rehabilitation and be supplemented by disability management, elderly care, etc. However, owing to the lack of legislative and policy supports, the local programs mostly failed to integrate existing resources for occupational, disability, and medical rehabilitation and elderly care. Therefore, they could neither design a social care system of rehabilitation nor effectively use the regional resources.

Lack of proper payment and pricing policy support

The pilot programs were generally constrained by provider payment and pricing policies. Owing to the lack of incentives, the pilot hospitals were not active enough in implementing pilot initiatives. Improper provider payment methods failed to incentivize care providers in delivering the needed rehabilitation or promote the development of two-way referral systems. With this, patients cannot be managed well.

Local health insurance agencies are suggested to initiate provider payment reforms to support rehabilitation delivery. First, basic rehabilitative services need to be placed into a benefit package of the publicly financed health insurance schemes, and those localities with strong pooling capacity can consider expanding the benefit package to cover elderly care and NCD rehabilitation. Second, quality indicators for rehabilitation, including indicators for acute and post-acute care, and referral indicators need to be developed and used for benchmarking performance-based payments. Third, health insurance agencies should work with health authorities in defining service packages and tariffs.

Rehabilitative care mostly involves clinical procedures; however, their prices are lower than the actual costs. This has discouraged health staff in delivering rehabilitative services, since doing so may incur losses on their part. Therefore, the central pricing agency shall cover rehabilitation in the National Medical Fee Schedule, and local pricing bureaus need to define rehabilitation prices on the basis of the local salary and price level.

Slow development of rehabilitative medicine with severe personnel shortage

Most pilots have had inadequate human resources for delivering rehabilitation and observed uneven care quality. Poor competency of primary and secondary hospitals was a widespread issue. Therefore, patients were stuck in rehabilitation units of tertiary hospitals, delaying rehabilitative medicine and system building. All pilot health facilities observed improvements in infrastructures in the past two years, such as bed number increase; however, personnel development was lagging behind with severe shortage of rehabilitation doctors, therapists, and nurses. As a result, many health facilities, especially primary hospitals, could not provide rehabilitation owing to the lack of doctors and nurses.

Heavy disease burden owing to the lack of financial protection for patients

Except for Beijing and Zibo, most pilot areas observed low compensation to rehabilitative services by public health insurance schemes. Patients were facing heavy disease burdens and dissatisfied with the reimbursement policies.

Monitoring and supervision required for public private partnership

Many pilot programs encouraged public private partnership in delivering rehabilitation, and private hospitals have even become backbones in organizing and managing rehabilitation delivery. However, owing to the lack of policy backup, many private hospitals had personnel shortage and difficulties in becoming designated hospitals for public health payers. As a result, most private hospitals could not play a big role in promoting rehabilitative care. Some private hospitals even had problems with payment frauds and improper provider behaviors.

Look beyond the pilots

The nationwide pilot programs on the integrated rehabilitative services are a daring effort made by the national and local governments in China. It seems that the nationwide pilot program promoted care integration at different localities, especially where decision makers had given more political commitments and joint policy supports. In the next stage, the central health decision-makers are advised to develop well-concerted policies with pricing and health insurance agencies to encourage local decision-makers to be innovative in trialing new measures to reform pricing and health insurance policies. Further, a legislation may need to be drafted to pool resources and differentiate the responsibilities of the different parties.

Edited by Yang Pan and Pei-Fang Wei

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

References

- 1.CPC Central Committee and the State Council. Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health Care System [in Chinese]. http://www.gov.cn/test/2009-04/08/content_1280069.htm. Published March 17, 2009. Accessed September 10, 2016.

- 2.Huang Y.L. Research on developing community-based rehabilitation in the background of health reform [in Chinese] J Fujian Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2011;21:65–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling T.Y., Wang H., Wang X.L. Survey on community health needs of patients with cerebral vascular diseases [in Chinese] Chin General Pract. 2005;8:249–251. [Google Scholar]

- 4.He F. Continuous standard home-based rehabilitation for stroke patients [in Chinese] Mod Med Heal. 2007;18:2790–2791. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Civil Affairs. 2015 Statistical Communiqué of Social Service Development [in Chinese]. http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/zwgk/mzyw/201607/20160700001136.shtml. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 6.The State Council of the People's Republic of China. The 13th Five-Year Plan for Aging and Aging Care Development [in Chinese]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-03/06/content_5173930.htm. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed 28 April 2017.

- 7.Chinese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine . 2009. The National Survey on Medical Rehabilitation Resources [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B.H., Mi Z.X., Cheng J. Research on rehabilitation medical service system construction in China [in Chinese] Chin Hosp. 2012;16:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Development Research Center . China National Health Development Research Center; Beijing: 2013. Final Evaluation Report on Integrated Rehabilitative Care Pilots in 46 Cities in 14 Provinces [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health and Family Planning Commission. 2013 Year Book of National Statistics on Health and Family Planning in China [in Chinese]. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2013/index2013.html. Accessed May 25, 2016.