Abstract

Purpose

The objective was to assess whether dyspnea, peripheral muscle strength and the level of physical activity are correlated with life-space mobility of older adults with COPD.

Patients and methods

Sixty patients over 60 years of age (40 in the COPD group and 20 in the control group) were included. All patients were evaluated for lung function (spirometry), life-space mobility (University of Alabama at Birmingham Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment), dyspnea severity (Modified Dyspnea Index), peripheral muscle strength (handgrip dynamometer), level of physical activity and number of daily steps (accelerometry). Groups were compared using unpaired t-test. Pearson’s correlation was used to test the association between variables.

Results

Life-space mobility (60.41±16.93 vs 71.07±16.28 points), dyspnea (8 [7–9] vs 11 [10–11] points), peripheral muscle strength (75.16±14.89 vs 75.50±15.13 mmHg), number of daily steps (4,865.4±2,193.3 vs 6,146.8±2,376.4 steps), and time spent in moderate to vigorous activity (197.27±146.47 vs 280.05±168.95 minutes) were lower among COPD group compared to control group (p<0.05). The difference was associated with the lower mobility of COPD group in the neighborhood.

Conclusion

Life-space mobility is decreased in young-old adults with COPD, especially at the neighborhood level. This impairment is associated to higher dyspnea, peripheral muscle weakness and the reduced level of physical activity.

Keywords: COPD, elderly, mobility limitation, dyspnea, muscular weakness

Introduction

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide and impairs the respiratory, musculoskeletal and psychological systems as well as social skills.1,2 These disorders are associated with functional disability and low health-related quality of life.1 Progressive functional disability is commonly observed in older adults3 and leads to the need for help to carry out the activities of daily living (ADL).4 This functional dependence can occur early in older adults with COPD due to dyspnea, sarcopenia and low level of physical activity often related to the respiratory disorder.5

Mobility is highly related to health state, autonomy, independence, quality of life and need for care, especially among older adults. These factors must be considered in the evaluation of the older population to develop strategies for prevention and treatment of health problems.6 Life-space mobility refers precisely to the capacity, frequency and independence with which individual moves within the house, around the neighborhood and in other cities.7 Mobility can be affected by environmental, cognitive and physical factors, and the loss of life-space mobility among older adults appears to lead to worse quality of life,8 social isolation,9 symptoms of depression10 and, possibly, physical inactivity. The association between chronic diseases and limited life-space mobility has been demonstrated among older patients with kidney disease,11 fecal incontinence12 and stroke sequelae,13 but it has never been evaluated in the case of older patients with chronic respiratory diseases.

Physical inactivity is an important predictor of mortality in healthy older adults and also in patients with chronic diseases.14,15 Most COPD patients do not follow the current minimum recommendations for physical activity and have lower level of physical activity than healthy individuals.16,17 Daily symptoms such as dyspnea and fatigue17 as well as environmental and sociodemographic factors,18 exacerbations19 and comorbidities20 influence the low levels of physical activity among these patients. The level of physical activity in COPD individuals can be evaluated through questionnaires.21 Questionnaires are low cost and easy to apply. They are generally used in epidemiological studies and large clinical trials.21 A variety of questionnaires have been designed to obtain data on different aspects of daily physical activity, including its intensity, type, quantity and limitations to perform ADL.21 Another way to assess the level of physical activity is the application of motion sensors,22 such as accelerometers. These provide more accurate, individualized and detailed information about body movements than questionnaires.21 However, accelerometers have some disadvantages; accelerometers are high cost needing technical expertise to manipulate and a “software” to analyze the obtained data.21 Furthermore, a general concern about motion sensors is the collaboration of the evaluated individual. For example, such individual should remember to put on and properly place the device.23

Low levels of physical activity in COPD older adults are related to higher risk of hospital readmission24 and lower survival.25 Thus, given the close relationship between the levels of physical activity and health, their assessment is very important.26 Considering that reduced life-space mobility can affect the older adults’ quality of life and level of independence more directly than physical inactivity, understanding the impact of COPD and the existence of any relationship between modifiable factors in the level of life-space mobility is necessary. The aim of this study was to assess whether dyspnea and peripheral muscle strength affect life-space mobility and the level of physical activity of older adults with COPD.

Patients and methods

Participants

This controlled cross-sectional study was conducted at Pneumology Service, Conjunto Hospitalar do Mandaqui, Brazil. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Cidade de São Paulo (CAAE: 29380314.0.0000.0064) and the Ethics Committee of the Conjunto Hospitalar do Mandaqui (CAAE: 29380314.0.3001.5551), and all patients signed an informed consent form. Forty COPD patients out of 90 selected individuals were included in the respiratory diseases outpatient clinic. Other 20 healthy patients with corresponding age (control group) were included, in accordance with the calculated sample size, considering an expected effect size of 0.8, 80% of power and alpha of 5%, with allocation of 2:1. All eligible participants were older adults over 60 years of age, according to the United Nations definition for older persons from developing countries,27–29 had no musculoskeletal or cognitive limitations that could interfere in the assessments and had not participated in regular physical activity in the last 6 months. The inclusion criteria for the COPD group were: monitoring in the Pulmonology Outpatient Clinic of the Conjunto Hospitalar do Mandaqui for at least 6 months, forced expiratory volume in the first second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) <70% predicted after bronchodilator1 and absence of heart disease or any other non-pulmonary cause of respiratory symptoms certified by the doctor. Inclusion criteria for the control group were: absence of respiratory symptoms or medical diagnosis of any chronic pulmonary disease, no history of smoking and lack of spirometric changes. Exclusion criteria for both groups were: inability to complete all assessments, use of accelerometer for less than 3 consecutive days30 and modification of the clinical condition (hospitalization, emergency room visit or use of new medication) during the evaluation period.

Procedures

Patients included in the study and allocated in the COPD and control groups received detailed explanations on how to perform each procedure. After this, they were evaluated for clinical and anthropometric history, lung function, life-space mobility, dyspnea severity and peripheral muscle strength. After all assessments, which took 30 minutes on average, an accelerometer was fixed to the waist of the patient and removed after 1 week.

Measurements

Clinical and anthropometric measurements

Height and weight were measured according to National Institute of Health, Heart, Lung and Blood guidelines.31 Information on other diseases, smoking, alcohol consumption, respiratory symptoms (cough, expectoration, wheezing and dyspnea) and the presence of COPD was requested from the patients.1 COPD severity was defined according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2017 guidelines.1

Pulmonary function

Simple spirometry was performed according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society consensus criteria.32 FEV1, FVC and forced expiratory flow at the moment between 25% and 75% of the curve (FEF25%–75%) were analyzed in absolute values and in the reference values previously described for the Brazilian population.33

Life-space mobility

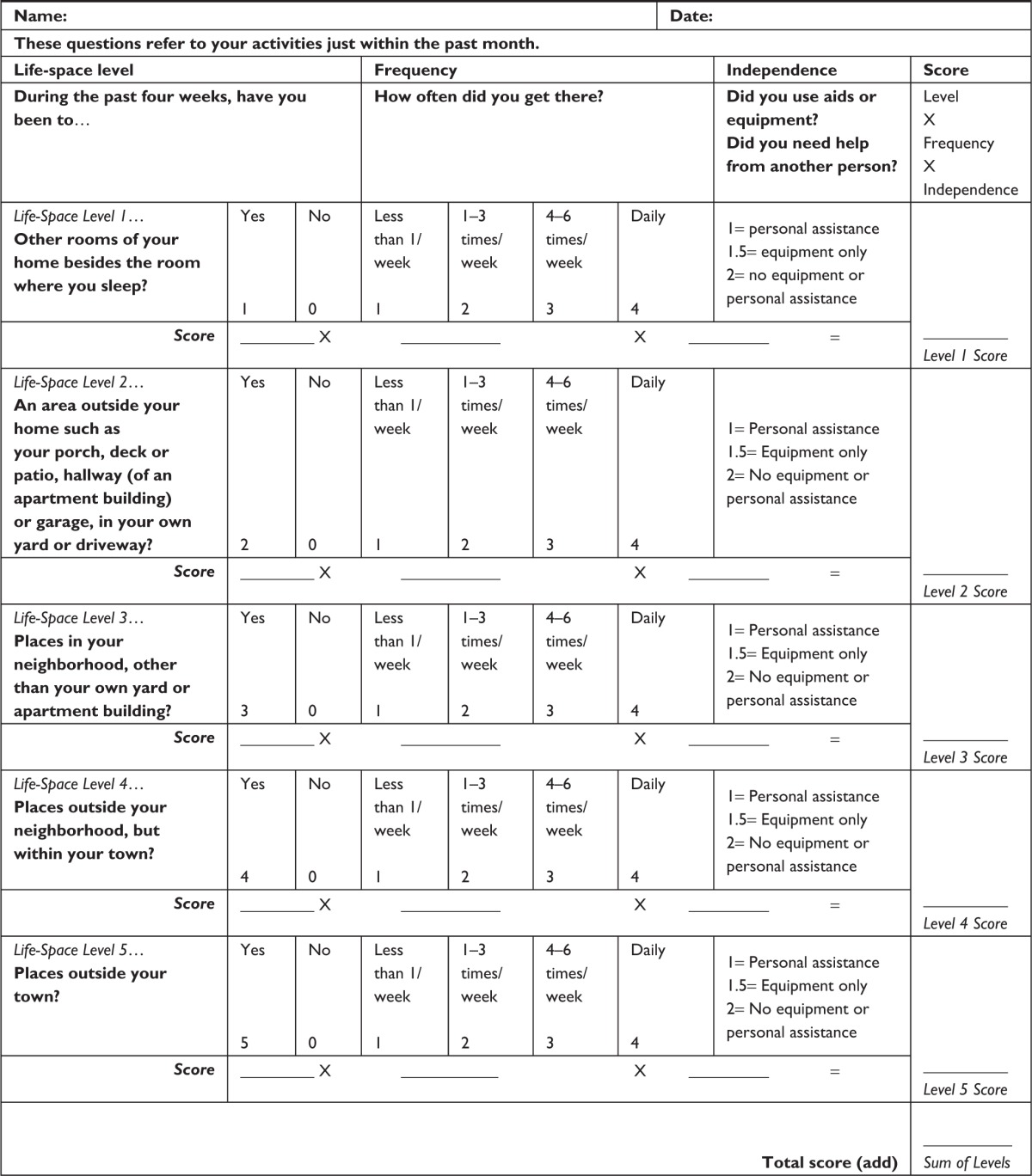

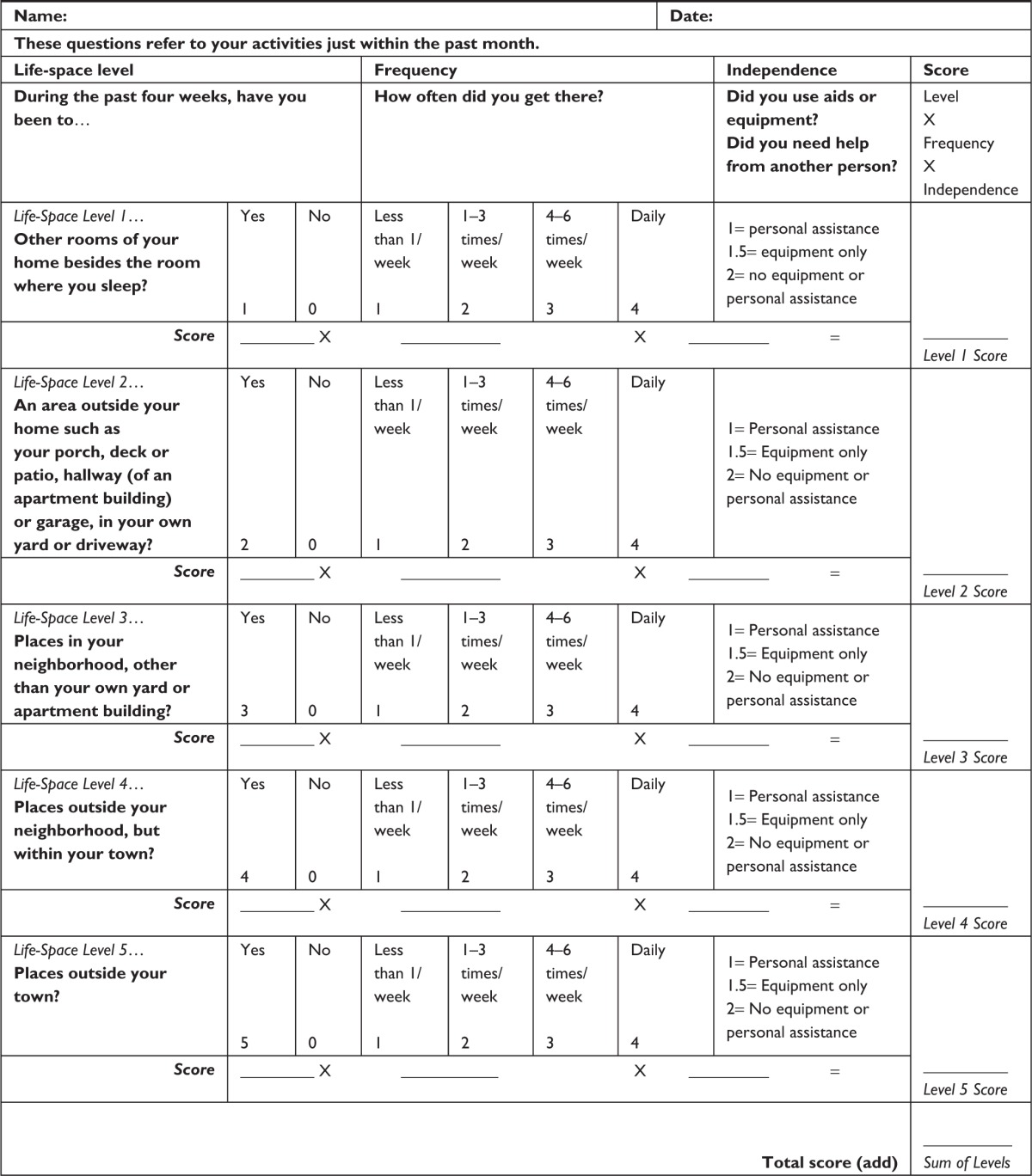

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment7,34 questionnaire, culturally adapted to the Brazilian population, was used. This questionnaire consists of questions on five levels of spaces visited by the older adult in the 4 weeks prior to the assessment, including the following items: life-space level (sleeping room, internal housing area, external housing area, neighborhood, within the city and other cities), frequency (less than 1 time per week, 1–3 times a week, 4–6 times a week or daily) and independence (personal assistance, equipment assistance, without assistance) (Table S1).6,7 The score ranges from 0 to 120 and is obtained by combining the scores in each life-space level. Higher scores indicate greater life-space mobility.7

Severity of dyspnea

The “Modified Dyspnea Index” (MDI) questionnaire adapted to Brazilian Portuguese35 was used. The MDI is an instrument composed of three components: functional impairment, magnitude of the task and magnitude of the effort. The total score ranges from 0 to 12, as a result of the sum of scores (from zero to four) of each MDI component. The lower the score, the more severe the dyspnea.35

Peripheral muscle strength

A “handgrip” dynamometer was used. The measurement was performed with the dominant hand of the evaluated individual, respecting the protocol recommended by the American Association of Hand Therapists.36 The mean of the three measurements was used37 in its absolute value and in the reference value previously described for the Brazilian population.38

The level of physical activity and the number of daily steps

The accelerometer was used for 24 hours on 7 consecutive days. Accelerometers were installed in the waist of the patient using elastic straps.39 The collected values were adjusted for age, weight, height, gender and race. The mean of the values collected during 7 days of the following variables were analyzed: number of daily steps; percentage of daily time in sedentary, light, moderate and vigorous activity; and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA).

Statistical analysis

After descriptive analysis and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test, the groups were compared using the unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney tests to observe the initial homogeneity of groups and test the primary objective. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to test the relationship between mobility in the COPD group and dyspnea severity, peripheral muscle strength and physical activity level. We consider the correlation weak when r=0.10 to 0.29, moderate when r=0.30 to 0.49 and strong when r=0.50 to 1.40 The level of significance was set at 5%.

Results

Demographic comparison and initial clinical situation

Out of the 90 eligible patients, sixty adults over 60 years of age were included in the study; 40 were in the COPD group (29 GOLD II, 10 GOLD III and 1 GOLD IV) and 20 in the control group. The other 30 eligible patients did not agree to participate in the study due to the need to use the accelerometer. The two groups were similar in gender, age, body mass index, comorbidities, alcohol consumption and number of retirees. The mean age of participants in both groups classifies them as young-old adults.41 As expected, respiratory symptoms and spirometric variables were altered in the COPD group compared to the control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic comparison and initial clinical situation of groups (n=60)

| Variables | COPD (n=40) |

Control (n=20) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 20 (50%) | 13 (65%) | 0.40 |

| Age, years | 66.95±5.87 | 65.95±4.55 | 0.50 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.65±5.06 | 27.71±5.20 | 0.50 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 25 (62.5%) | 15 (37.5%) | 0.28 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 12 (30%) | 6 (30%) | 0.76 |

| SAH, n (%) | 22 (55%) | 9 (45%) | 0.64 |

| CHF, n (%) | 7 (17.5%) | 5 (25%) | 0.51 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 7 (17.5%) | 4 (20%) | 1.00 |

| Retirees, n (%) | 16 (40%) | 12 (60%) | 0.23 |

| FEV1 % of the predicted | 59.05±12.44 | 91.50±12.47 | <0.001 |

| FVC, % of the predicted | 63.12±10.06 | 91.25±15.56 | <0.001 |

| FEF25%–75%, % of the predicted | 46.67±10.49 | 85.95±17.11 | <0.001 |

| Cough, n (%) | 12 (30%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Expectoration, n (%) | 12 (30%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Wheezing, n (%) | 21 (52.5%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 33 (82.5%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or absolute number (frequency). FEV1, FVC and FEF25%–75% are expressed as % of predicted.33

Abbreviations: n, absolute number; BMI, body mass index; SAH, systemic arterial hypertension; CHF, congestive heart failure; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEF25%–75% = forced expiratory flow at the moment between 25% and 75% of the curve, p-value of the t-test or chi-square test.

Mobility, dyspnea, peripheral strength and level of physical activity

Results of overall mobility, dyspnea severity, mean percentage of time spent in moderate-intensity activity, MVPA and number of daily steps were different between the groups (Table 2). The significant difference found in mobility between the groups showed statistical power of 83% with p<0.05.

Table 2.

Comparison of mobility, dyspnea severity, peripheral muscle strength and level of physical activity between groups (n=60)

| Variables | COPD (n=40) |

Control (n=20) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall mobility, pts | 60.41±16.93 | 71.07±16.28 | 0.02 |

| Severity of dyspnea, pts | 8 (7–9) | 11 (10–11) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral strength, % of the predicted | 75.16±14.89 | 75.50±15.13 | 0.94 |

| Sedentarism, % of the time | 84±5 | 82±4 | 0.12 |

| Light activities, % of the time | 13±4 | 14±3 | 0.26 |

| Moderate activities, % of the time | 1±1 | 2±1 | 0.04 |

| Vigorous, % of the time | 0.04±0.02 | 0.02±0.03 | 0.61 |

| MVPA, minutes | 197.27±146.47 | 280.05±168.95 | 0.04 |

| Daily steps | 4,865.4±2,193.3 | 6,146.8±2,376.4 | 0.04 |

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or absolute number (frequency) or median (interquartile range 25%–75%); peripheral force is expressed as % of the predicted;38 p-value of t-, chi-square and Mann–Whitney tests.

Abbreviations: n, absolute number; pts, points; % of the time = percentage of time in activities of different intensities; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity index.

Life-space mobility

Groups differed only in the total score (p=0.02; test power =0.83) and in the score of life-space level 3 (p=0.03; test power =0.79), which refers to displacement to places in the neighborhood (Table 3).

Table 3.

Scores of patients with and without COPD on each life-space level

| Life-space | COPD (n=40) |

Control (n=20) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score, pts (min–max) | 60 (22–90) | 71 (43.5–110) | 0.02 |

| Other rooms in the house besides the sleeping room, pts (min–max) | 8 (8–8) | 8 (8–8) | 0.72 |

| Areas outside the house, pts (min–max) | 16 (16–16) | 16 (16–16) | 0.35 |

| Places in the neighborhood, pts (min–max) | 21 (12–24) | 24 (18–24) | 0.03 |

| Places outside the neighborhood, pts (min–max) | 16 (8–22) | 16 (13–30) | 0.53 |

| Places outside the city, pts (min–max) | 0 (0–10) | 0 (0–10) | 0.60 |

Notes: Data are presented as median (interquartile range 25%–75%); p-value of Mann–Whitney test; questions on five levels of spaces visited by the older adult in the 4 weeks prior to the assessment, including the following items: life-space level, frequency and independence; total score ranges from 0 to 120; other rooms in the house besides the sleeping room (range from 0 to 8 points); areas outside the house (range from 0 to 16 points); places in the neighborhood (range from 0 to 24 points); places outside the neighborhood (range from 0 to 32 points); and places outside the city (range from 0 to 40 points).

Abbreviations: pts, points; min, minimum; max, maximum.

Correlation between mobility and dyspnea, peripheral strength and accelerometry

Moderate and positive correlations were observed between mobility, assessed through the University of Alabama at Birmingham Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment questionnaire in COPD older adults, and the average percentage of time spent in moderate-intensity activity (r=0.40; p=0.01), number of daily steps (r=0.43; p=0.01), MVPA (r=0.43; p=0.01), dyspnea severity (r=0.44; p<0.001) and peripheral muscle strength (r=0.42; p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between mobility and dyspnea severity, peripheral muscle strength and accelerometry variables of the COPD group

| Accelerometry variables | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea severity | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral strength | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Sedentarism, % of the time | −0.24 | 0.13 |

| Light activities, % of the time | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| Moderate activities, % of the time | 0.40 | 0.01 |

| Vigorous activities, % of the time | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| MVPA, minutes | 0.43 | 0.01 |

| Daily steps | 0.43 | 0.01 |

Note: p-value of the Pearson’s correlation test.

Abbreviation: MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity index.

Discussion

Our results showed that young-old adults with COPD had poor life-space mobility, especially to move within their neighborhood, when compared to young-old adults without lung disease. This impaired mobility is associated with dyspnea severity, peripheral muscle weakness and reduced physical activity level. The novelty of our study is the demonstration of the association between all these variables, as well as their impact on one aspect not explored before such as life-space mobility, using an appropriate tool for this population.

The lowest level of mobility found among COPD older adults was associated with lower number of daily steps and less time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activities compared to healthy young-old adults. The ability to move within the community has never been evaluated in this population, but the present results are consistent with previous studies showing lower level of physical activity in COPD patients than in healthy individuals of same age and gender.16,42 It is known that this aspect may be associated with poor prognosis of the COPD43 and may cause adverse effects on these patients, particularly to their quality of life.44 The loss of quality of life can be even greater if we consider that the lowest score obtained by the young-old adults was related to visiting places in the neighborhood. Possibly, this decreased independence is one of the barriers to engaging in social activities,45 leading to a greater propensity to loneliness45 and difficulties to perform the ADL.16 Therefore, supplementary programs to treatment of COPD, such as pulmonary rehabilitation, should pay special attention to life-space mobility because this aspect better reflects the real life of this population than other variables traditionally measured, such as the 6-minute walk test.46 Furthermore, this would enhance other known benefits that aim to interfere in social interaction, depression and quality of life.47

Although it is believed that COPD patients with moderate airway obstruction have few clinical consequences and, therefore, do not require rehabilitation, there is evidence that moderate airway obstruction is associated with reduced exercise capacity and level of physical activity in this population.16 Structural abnormalities such as pulmonary air trapping, airway wall thickening, and vascular dysfunction48 contribute to increased ventilatory demand and compromise the ventilatory mechanics of patients with COPD.49 Thus, patients often restrict some more intense activities to avoid unpleasant symptoms, such as dyspnea.50 Over time, this can lead to a spiral of worsening symptoms, deconditioning and exercise intolerance as patients become progressively more sedentary.50 In addition, cardiocirculatory51 and musculoskeletal impairments52 have been reported in patients with mild to moderate COPD, as observed in the majority of young-old adults with COPD in our sample, which may also lead to reduced exercise capacity and ADL limitation.

Besides reflecting the level of physical activity and the ability to perform ADL, mobility was shown to be associated with dyspnea, which is considered the main symptom leading to limited exercise among COPD patients, often causing inactivity and deconditioning of peripheral muscles.53 In another study, a strong association between limited ADL, as assessed through the London Chest Activity of Daily Living scale, and the degree of dyspnea, measured through the Medical Research Council scale, was observed.54 Weakness of skeletal muscles in COPD patients can be attributed to isolated or combined effects of deconditioning induced by inactivity, systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, smoking, aging, low levels of anabolic hormones, nutritional impairment and use of corticosteroids.47 According to our results, this weakness interferes with the ability to attend places in the neighborhood with independence. This interference has been reported in another study with COPD patients. The study showed that weakness of the quadriceps was associated with reduced level of daily physical activity.55

Accelerometry provides accurate, individualized and detailed information on body movement, especially among individuals with typical slow gait, such as older adults with COPD.14 Other authors who have used accelerometers to assess the level of physical activity among COPD patients have shown that the active time of these patients is correlated with the quadriceps strength.56 Similar results were observed in our study; there was a slight correlation between life-space mobility, physical activity and peripheral muscle strength among young-old adults with COPD. Therefore, we believe that the evaluation of life-space mobility is appropriate to provide information not just on mobility but also on the level of physical activity of young-old adults with COPD.

Systemic effects of COPD such as dyspnea and fatigue can lead to decreased exercise tolerance, favoring a vicious cycle that results in generalized muscle weakness, sedentarism and physical inactivaty.57 However, pulmonary rehabilitation programs can improve dyspnea, functional balance, muscle strength and exercise tolerance among COPD patients.58 The University of Alabama at Birmingham Study of Aging Life-Space questionnaire showed good correlation with the accelerometer data in the present study. This shows that this questionnaire is an excellent tool to evaluate the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation programs with regard to actual daily mobility instead of only considering the performance capacity of these patients. Furthermore, this questionnaire can be used in future studies with other populations because it is an easily applied and interpreted tool.

A limitation of this study was a low number of patients with severe and very severe COPD, which may have underestimated the results for life-space mobility limitation. This may have occurred because we collected data from an outpatient clinic, which naturally requires patients to get out of their homes; we hypothesize that patients with severe and very severe COPD had life-space mobility limited to a point that they were not able to attend this clinic and thus were the minority in our sample. Also, we recognize that our sample is younger than that expected for older adults with COPD, but this can be a characteristic of patients with COPD in Brazil, as observed in previous studies.59,60 Furthermore, patients were not questioned about the reasons that led them to not attend spaces, such as dyspnea, lack of motivation, architectural barriers, and financial conditions. This would allow the comparison of factors that influence decreased mobility among young-old adults with and without COPD. Another point should be the difference in the age of subjects considered elderly in our study and in the developed countries. The World Health Organization considers subjects over 60 years of age as elderly in developing countries, such as Brazil.29 However, this population with worse conditions of health and education should be similar to subjects with 65 years from developed countries with the same disease severity. Therefore, our results may be generalizable to other countries. However, we believe that addressing this aspect would be important in future studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results showed that life-space mobility is reduced in young-old adults with COPD when compared to older adults without lung illness, especially in relation to displacement within the neighborhood. We also observed that reduced life-space mobility is related to dyspnea severity, peripheral muscle weakness and reduced physical activity assessed by accelerometry.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment™

|

Notes: Reprinted from Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, et al. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10): 1008–1119; with permission of Oxford University Press.1

Abbreviation: UAB, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Reference

- 1.Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, et al. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10):1008–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study. This project was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant numbers 2012/16817-3 and 2015/12614-9). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions

IFFG, CTT, MdSMPS, ISL and ACL contributed to the concept and design of this study and undertook data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed toward drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD [webpage on the Internet] [Accessed April 30, 2017]. Available from: www.goldcopd.org.

- 2.Borges-Santos E, Wada JT, da Silva CM, Silva RA, et al. Anxiety and depression are related to dyspnea and clinical control but not with thoracoabdominal mechanics in patients with COPD. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;210:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cólon-Emeric CS, Whitson HE, Pavon J, Hoenig H. Functional decline in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(6):388–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanervisto M, Saarelainen S, Vasankari T, et al. COPD, chronic bronchitis and capacity for day-to-day activities: negative impact of illness on health-related quality of life. Chron Respir Dis. 2010;7(4):207–215. doi: 10.1177/1479972310368691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joppa P, Tkacova R, Franssen FM, et al. Sarcopenic obesity, functional outcomes, and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(8):712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allman RN, Sawyer P, Roseman JM. The UAB study of aging: background and insights into life-space mobility among older Americans in rural and urban settings. Aging Health. 2006;2(3):417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, et al. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10):1008–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Litaker MS, et al. Association between aspects of oral health-related quality of life and body mass index in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1808–1816. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locher JL, Ritchie CS, Roth DL, Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Social isolation, support, and capital and nutritional risk in an older sample: ethnic and gender differences. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(4):747–761. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polku H, Mikkola TM, Portegijs E, et al. Life-space mobility and dimensions of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(9):781–789. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.977768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowling CB, Muntner P, Sawyer P, et al. Community mobility among older adults with reduced kidney function: a study of life-space. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(3):429–436. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):629–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh-Park M, Hung C, Chen P, Barrett AM. Severity of spatial neglect during acute inpatient rehabilitation predicts community mobility after stroke. PMR. 2014;6(8):716–722. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manini TM, Everhart JE, Patel KV, et al. Daily activity energy expenditure and mortality among older adults. JAMA. 2006;296(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Physical activity and mortality in men and women with diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(2):156–160. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32831f1b77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Troosters T, Sciurba F, Battaglia S, et al. Physical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-study. Respir Med. 2010;104:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waschki B, Spruit MA, Watz H, et al. Physical activity monitoring in COPD: compliance and associations with clinical characteristics in a multicenter study. Respir Med. 2012;106(4):522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alahmari AD, Mackay AJ, Patel ARC, et al. Influence of weather and atmospheric pollution on physical activity in patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2015;16:71. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0229-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alahmari AD, Patel ARC, Kowlessar BS, et al. Daily activity during stability and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nussbaumer-Ochsner Y, Rabe KF. Systemic manifestations of COPD. Chest. 2011;139(1):165–173. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, Spruit MA, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Quantifying physical activity in daily life with questionnaires and motion sensors in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(5):1040–1055. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00064105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, Magnussen H. Physical activity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(2):262–272. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00024608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kochersberger G, McConnell E, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper C. The reliability, validity, and stability of a measure of physical activity in the elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(8):793–795. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Aymerich J, Farrero E, Felez MA, Izquierdo J, Marrades RM, Anto JM. Risk factors of readmission to hospital for a COPD exacerbation: a prospective study. Thorax. 2003;58(2):100–105. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yohannes AM, Baldwin RC, Connolly M. Mortality predictors in disabling chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in old age. Age Ageing. 2002;31(2):137–140. doi: 10.1093/ageing/31.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montoye HJ. Introduction: evaluation of some measurements of physical activity and energy expenditure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(Suppl 9):S439–S441. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nations U. Guidelines for Review and Appraisal of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing – Bottom-up Participatory Approach. New York: United Nations; 2006. p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nations U. Guide to the National Implementation of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. New York: United Nations; 2008. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nations U. Current Status of the Social Situation, Well-being, Participation in Development and Rights of Older Persons Worldwide. New York: United Nations; 2011. p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plasqui G, Bonomi AG, Westerterp KR. Daily physical activity assessment with accelerometers: new insights and validation studies. Obes Rev. 2013;14(6):451–462. doi: 10.1111/obr.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institutes of Health (US) Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira CAC. Espirometria – Diretrizes para Testes de Função Pulmonar. J Bras Pneumol. 2002;28(Suppl 3):S1–S82. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curcio CL, Alvarado BE, Gomez F, Guerra R, Guralnik J, Zunzunegui MV. Life-Space Assessment scale to assess mobility: validation in Latin American older women and men. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;25(5):553–560. doi: 10.1007/s40520-013-0121-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miura CTP, Gallani MCBJ, Domingues GBL, Rodrigues RCM, Stoller JK. Adaptação cultural e análise da confiabilidade do instrumento Modified Dyspnea Index para a cultura brasileira. Rev Latinoam Enferm. 2010;18(5):1020–1030. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692010000500025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fess EE. Grip strength. In: Casanova JS, editor. Clinical Assessment Recommendations. Chicago (IL): American Society of Hand Therapists; 1992. pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishigaki EY, Ramos LG, Carvalho ES, Lunardi AC. Effectiveness of muscle strengthening and description of protocols for preventing falls in the elderly: a systematic review. Braz J Phys Ther. 2014;18(2):111–118. doi: 10.1590/S1413-35552012005000148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novaes RD, Miranda AS, Silva JO, Tavares BVF, Dourado VZ. Equações de referência para a predição da força de preensão manual em brasileiros de meia idade e idosos. Fisioter Pesqui. 2009;16(3):217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung VH, Gray L, Karunanithi M. Review of accelerometry for determining daily activity among elderly patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):998–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Bouter LM, Vet HC, Terwee CB. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(2):105–113. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zizza CA, Ellison KJ, Wernette CM. Total water intakes of community-living middle-old and oldest-old adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(4):481–486. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pitta F, Troosters T, Spruit MA, Probst VS, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Characteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:972–977. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Serra I, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Time-dependent confounding in the study of the effects of regular physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an application of the marginal structural model. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown DW, Pleasents R, Ohar JA, et al. Health-related quality of life chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in North Carolina. N Am J Med Sci. 2010;2(2):60–65. doi: 10.4297/najms.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Croft JB, Anderson LA, Wheaton AG, Presley-Cantrell LR, Ford ES. The association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, disability, engagement in social activities, and mortality among US adults aged 70 years or older, 1994–2006. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;15(9):75–83. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S53676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;18(4):CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guenette JA, Jensen D, Webb KA, Ofir D, Raghavan N, O’Donnell DE. Sex differences in exertional dyspnea in patients with mild COPD: physiological mechanisms. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177(3):218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chin RC, Guenette JA, Cheng S, et al. Does the respiratory system limit exercise in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(12):1315–1323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1970OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ZuWallack R. How are you doing? What are you doing? Differing perspectives in the assessment of individuals with COPD. COPD. 2007;4(3):293–297. doi: 10.1080/15412550701480620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grau M, Barr RG, Lima JA, et al. Percent emphysema and right ventricular structure and function: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Lung and Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Right Ventricle Studies. Chest. 2013;144(1):136–144. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van den Borst B, Slot IG, Hellwig VA, et al. Loss of quadriceps muscle oxidative phenotype and decreased endurance in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:1319–1328. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00508.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Donnell DE. Hyperinflation, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(2):180–184. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-093DO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon KM, Carpes MF, Corrêa KS, Santos K, Karloh M, Mayer AF. Relationship between daily living activities (ADL) limitation and the BODE index in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2011;15(3):212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shrikrishna D, Patel M, Tanner RJ, et al. Quadriceps wasting and physical inactivity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(5):1115–1122. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, Spruit MA, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2006;129(3):536–544. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165–1185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jácome C, Marques A. Impact of pulmonar rehabilitation in subjects with mild COPD. Respir Care. 2014;59(10):1577–1582. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreira GL, Manzano BM, Gazzotti MR, et al. PLATINO, a nine-year follow-up study of COPD in the city of São Paulo, Brazil: the problem of underdiagnosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2014;40(1):30–37. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132014000100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Menezes AMB, Jardim JR, Perez-Padilla R, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated factors: the PLATINO study in São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2005;21(5):1565–1573. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000500030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment™

|

Notes: Reprinted from Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, et al. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10): 1008–1119; with permission of Oxford University Press.1

Abbreviation: UAB, University of Alabama at Birmingham.