Abstract

Brown and beige adipocytes expend chemical energy to produce heat and are therefore important in regulating body temperature and body weight. Brown adipocytes develop in discrete and relatively homogenous depots of brown adipose tissue, whereas beige adipocytes are induced to develop in white adipose tissue in response to certain stimuli — notably, exposure to cold. Fate-mapping analyses have identified progenitor populations that give rise to brown and beige fat cells and revealed unanticipated cell-lineage relationships between vascular smooth muscle and beige adipocytes, and between brown fat and skeletal muscle cells. Additionally, non-adipocyte cells in adipose tissue, including neurons, blood vessel-associated cells and immune cells play crucial roles in regulating the differentiation and function of brown and beige fat.

Introduction

Obesity occurs when energy consumption (from food) chronically exceeds energy expenditure and this dramatically increases the risk of developing many life-threatening diseases. Adipose tissues, which consist mainly of adipocytes, are important in regulating systemic energy levels. Two general classes of adipocytes are found in mammals: white and brown. Whereas white adipocytes store and release energy as fatty acids in response to systemic demands, brown adipocytes burn substrates, including fatty acids and glucose, to produce heat in response to various stimuli; this process is known as adaptive non-shivering thermogenesis.

The thermogenic activity of brown fat cells relies, to a great extent, on Uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), a protein that is localized on the inner membrane of mitochondria. When activated, UCP1 catalyzes the leak of protons across the mitochondrial membrane1, which uncouples oxidative respiration from ATP synthesis; the resulting energy derived from substrate oxidation is dissipated as heat (see Box 1).

Box 1. Uncoupling Protein-1.

Uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) is uniquely present in the inner mitochondrial membrane of brown and beige adipocytes. When activated, UCP1 translocates protons (H+) from the intermembrane space into the mitochondrial matrix. This dissipates the protonmotive force used by ATP synthase and increases respiratory chain activity. The available energy from substrate oxidation is thus converted to heat129, 130. Importantly, the activity of UCP1 is tightly regulated. Under basal conditions, proton leak through UCP1 is inhibited by purine nucleotides. Norepinephrine (NE), secreted by nerve fibers in response to cold-exposure, Leptin and certain other stimuli, triggers a signaling cascade in brown adipocytes that induces lipolysis and activates UCP1 function. Specifically, long chain fatty acids liberated by lipolysis bind to UCP1 and activate UCP1-catalyzed proton leak1, 129. A recent study also demonstrates that mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), which accumulate in stimulated brown fat cells, enhances UCP1-mediated respiration by promoting the sulfenylation of a cysteine residue in UCP1 itself131. Thus, the protein levels of UCP1 in brown or beige fat reflect the thermogenic capacity but UCP1 must be activated to increase thermogenesis.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is organized into several discrete depots that are specialized for the efficient production and distribution of heat. BAT is densely innervated by the sympathetic nervous system and, in many cases, nerve fibers directly synapse onto brown adipocytes. Cold, which is sensed by the central nervous system, stimulates sympathetic outflow to BAT and noradrenaline secreted by nerve fibers interacts with adrenergic receptors on brown adipocytes to activate thermogenesis2. BAT is also very highly vascularized, which allows substrates and oxygen to be delivered to brown adipocytes for thermogenesis and the resultant heat to be distributed to the rest of the body3.

UCP1-expressing and mitochondrial-rich adipocytes also develop within WAT depots in response to cold exposure and certain other stimuli4 and these adipocytes have consequently been termed ‘beige’ or ‘brite’ (brown-in-white) adipocytes. Beige fat is defined as the clusters of UCP1-expressing adipocytes that reside outside of traditional brown fat depots. Like brown adipocytes, beige adipocytes have the capacity to convert energy into heat4.

Brown and beige fat are major sites of adaptive thermogenesis in mice and the activity of these tissues can significantly contribute to whole body energy expenditure. In humans, BAT was previously thought to exist in meaningful amounts only in infants and to regress and become metabolically inconsequential in adults. However, in the past several years, positron-emission tomography (PET) imaging studies of glucose uptake have uncovered the presence of substantial deposits of thermogenic fat in adult humans5–8. Marker gene expression analyses shows that these tissues express UCP1 and further suggest that certain human depots are analogous to rodent BAT whereas other depots have a beige-like profile9–12.

As mentioned above, cold exposure is a potent trigger for thermogenesis in brown and beige fat, and certain strains of mice lacking UCP1 cannot survive in the cold13. High calorie or high fat diets also induce BAT thermogenesis14, which curbs obesity in mice and depends on UCP1 function15. Mice lacking BAT are highly susceptible to obesity16 whereas mice with elevated brown and/or beige fat function are protected against many harmful metabolic effects of a high fat diet, including obesity and insulin resistance17–22.

In humans, high levels of brown and beige fat activity also correlate with leanness, suggesting that there could be an important natural role for brown and beige fat in human metabolism5, 6, 23. As well as being induced by cold exposure, human BAT or beige fat activity and energy expenditure can be increased by treatment with β3-adrenergic agonists24, 25. Genetic evidence also suggests that BAT affects human energy metabolism and obesity susceptibility. For example, variants at the FTO locus, which are strongly associated with obesity, repress thermogenic pathways in adipocytes26. Regardless of whether deficiencies in the function of brown fat predispose to obesity, augmenting brown fat activity could have beneficial effect; consequently, there is a growing research effort aimed at understanding the regulation of brown and beige fat formation.

In this review, we discuss the origins of brown and beige fat cells and highlight key molecules that control the development and function of these cell types. We also discuss the important role of other adipose-resident cell types, including nerve fibers and immune cells, in regulating brown and beige fat thermogenesis. Finally, we identify important outstanding questions and issues that remain to be addressed.

Brown versus beige adipose tissue

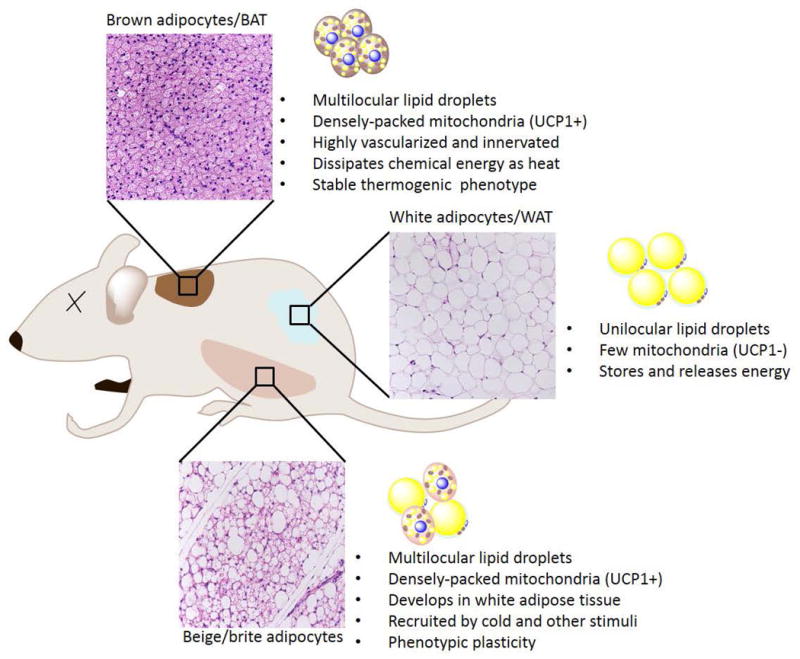

Brown and beige adipocytes share many morphological and biochemical characteristics: they contain many small lipid droplets (and are therefore termed multilocular, compared with unilocular white adipocytes) and densely-packed mitochondria; they express key thermogenic genes (Ucp1, Cidea, Pparα, Pgc1α); and they have the capacity to undergo thermogenesis in response to various stimuli (such as cold)4 (Fig. 1). Despite their similarities, however, brown and beige adipocytes also have distinguishing phenotypic (Table 1), and functional features. Most obviously, under unstimulated conditions, brown adipocytes have abundant mitochondria and express relatively higher levels of UCP1 and other thermogenic components, whereas beige adipocytes only express thermogenic components upon stimulation (at which point they do so at comparable levels to brown fat cells)12. This distinction between brown and beige fat cells is evident in vivo and ex vivo12, 27, suggesting that the stable thermogenic character of brown fat cells is at least partly fat-cell-autonomous. For example, adipogenic precursors isolated from BAT induce the expression of UCP1 during their conversion to adipocytes in culture27. Beige-fat-selective precursors or adipogenic precursor cells from WAT do not activate the thermogenic program in culture unless they are treated with additional inducers, such as thiazoledinediones28–31 or β-adrenergic agonists12. Thus, beige adipocytes have a flexible phenotype and can potentially carry out either energy storage or dissipation depending on the environmental or physiological circumstances.

Fig.1. Brown, white and beige adipocytes.

There are three types of adipocyte: brown, white and beige. Mice have a major interscapular BAT depot, as indicated. Brown adipocytes in brown adipose tissue (BAT) are characterized by the presence of multilocular lipid droplets and densely packed mitochondria containing uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). BAT is highly innervated and vascularized so that it can efficiently dissipate chemical energy as heat. White adipose tissue (WAT), dispersed in various subcutaneous and intra-abdominal depots, and contains mostly white adipocytes. White adipocytes are characterized by the presence of unilocular lipid droplets and few mitochondria that are devoid of UCP1. WAT is a major organ for the storage and release of energy. Beige adipocytes are found in various WAT depots and are especially prominent in the subcutaneous inguinal WAT. Beige fat cells develop in response to cold and certain other stimuli. Like brown adipocytes, beige cells have multilocular lipid droplets and densely packed UCP1+ mitochondria. Compared with brown adipocytes, beige adipocytes have more phenotypic flexibility, and can acquire a thermogenic or storage phenotype, depending on environmental cues.

Table 1.

Characteristics of brown, beige and white adipocytes

| Type | Location | Developmental Origins/Precursor type | Common Markers | Brown/Beige vs. White Markers | Brown vs. Beige Markers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipocyte | Pread | Adipocyte | Pread | Adipocyte | Pread | |||

Brown

|

Interscapular Cervical Axillary Perirenal |

• Myf5+, Pax7+, En1+ cells in dermomyotome |

Adipoq Fabp4 Pparγ C/EBPβ |

Pdgfrα Sca1 CD34 Pref1 CD29 |

Ucp1 Dio2 Cidea Ppargc1a Pparα Cox7a1 Cox8b Prdm16 Ebf2 |

Ebf2 |

Lhx8 Zic1 Eva1 Pdk4 Epstl1 |

|

Beige

|

WAT depots • Inguinal ≫ Epididymal |

Inguinal WAT • Ebf2+; PDGFRα+cells • Acta2+ smooth muscle cells • Myh11+ smooth muscle cells • Pdgfrβ+ mural cells Eoididvmal WAT • Bipotent Pdgfrα+ precursor |

Tbx1 Cited1 Shox2 CD137 TMEM26 PAT2 P2RX5 |

CD137 | ||||

White

|

Subcutaneous Visceral |

• Wt1+ mesothelial (visceral) |

Lep Retn Agt |

Wt1 (visceral fat) |

||||

Footnotes: Pref1 is a common marker for brown, beige, and white preadipocytes121. Wt1 is a specific marker of visceral white adipocyte progenitors in the mesothelium122. Brown fat-selective (vs. beige fat) markers include: Lxh8, Zic1, Eva1, Pdk4 and Epstl111, 12, 60. Beige fat-selective markers include: Tbx1, Cited1, Shox2, Cd137, TMEM26, PAT2, P2RX511, 12, 37, 60, 61. CD29 is a recently identified marker for isolation of human preadipocytes123. Cell surface markers are labeled in blue.

Initial indications that beige and brown adipocytes were distinct entities came from genetic studies led by Leslie Kozak. His group discovered that genetic variation between mouse strains influenced Ucp1 expression levels in WAT but not in BAT32. Primary adipocyte cell cultures from the subcutaneous fat of obesity-prone C57/BL6 and obesity-resistant SV129 mice also show strain-dependent differences in the levels of Ucp1 and other brown characteristics, indicating that the strain differences are, at least in part, adipose-cell-autonomous33. Metabolic analysis of recombinant strains shows that the degree of Ucp1 induction in WAT (that is, the abundance and activity of beige adipocytes) correlates very strongly with the capacity for treatment with β-adrenergic agonists to reduce obesity34. These studies also demonstrate that beige adipocytes suppress obesity, but only in the presence of sufficient levels of β-adrenergic activation.

Many core thermogenic components found in BAT are also expressed in beige adipocytes. However, beige adipocytes are uniquely equipped with an additional thermogenic mechanism separate from UCP1 function, which affects systemic energy homeostasis35. Specifically, mouse and human beige adipocytes can run a futile creatine cycle that wastes energy and produces heat in response to cold or β-adrenergic activation. Blocking this cycle reduces the thermogenic capacity of inguinal WAT (and conceivably other WAT depots) and leads to diminished whole-animal oxygen consumption. The existence of this UCP1-independent pathway for thermogenesis in adipocytes probably also explains, at least in part, the capacity for UCP1-deficient animals to survive in the cold through gradual acclimatization.

The formation of brown adipocytes

BAT depots

In mice, BAT depots form during embryogenesis before other adipose depots, providing newborns with a critical capacity for non-shivering thermogenesis and enabling them to acclimatize in the cold. Clusters of brown adipocytes that express the master adipocyte differentiation factor peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-γ (PPARγ) are detectable in the interscapular region of developing mice at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5)36. In adult mice, the major BAT depots are located in the dorsal anterior region and consist of the interscapular, cervical and axillary BAT. Infant humans also have interscapular BAT that has a molecular profile similar to that of classical rodent BAT37. Additional BAT depots in humans include the perirenal depot and an adipose depot in the deep neck region9.

Developmental origins of brown adipocytes

Fate-mapping studies in mice indicate that most brown adipocytes in the dorsal BAT depots originate from a mesodermal progenitor population in the somites38–40 (Fig. 2) (Table S1). This origin was first demonstrated by tracing the lineage of cells expressing the homeobox gene Engrailed-1 (En1)38. En1+ cells in the central dermomyotome develop into skeletal muscles of the back, dorsal (midline) dermis as well as interscapular and cervical brown adipocytes39, 40. Inducible lineage analyses showed that cells marked by early (E8.5–9.5) En1 expression predominantly give rise to brown adipocytes in anterior depots whereas an En1-expressing population at later stages is multipotent, contributing to brown fat, muscle and dermis38. These results suggest that multiple waves of En1+ cells exist, and that the early En1+ cells undergo brown fat commitment and lose En1 expression before acquiring other developmental potentials.

Fig. 2. Development of brown adipocytes.

Brown adipocytes are derived from a multipotent progenitor population in the dermomyotome that expresses En1, Pax7 and Myf5. During embryogenesis, these progenitors undergo commitment into brown fat preadipocytes and subsequently differentiate into mature brown adipocytes. Several transcription factors and signalling pathways have been implicated in regulating the development of brown adipose tissue (BAT): (1) EBF2 marks committed brown preadipocytes and might regulate brown adipose lineage specification; EWS interacts with YBX1 to regulate the transcription of BMP7, which promotes BAT development; (3) PRDM16 drives brown adipocyte differentiation through interactions with adipogenic transcription factors c/EBPβ and PPARγ; ZFP516 and EHMT1; (4) EBF2 cooperates with PPARγ to activate the brown fat-selective program.

Brown adipocytes are also marked by the prior developmental activation of Myf5 and Pax739, 40, which encode two transcription factors that mark myogenic precursor cells and carry out critical roles in skeletal myogenesis. Early Pax7 expression in the somite marks cells preferentially fated to brown fat whereas later Pax7 expression marks cells that are predominantly restricted to the skeletal muscle lineage40. Interestingly, Wnt signaling in the (later) multipotent En1-population drives dermal specification at the expense of both muscle and brown fat cell commitment38, suggesting that Wnt signaling regulates the divergence of dermal cells from cells that have both myogenic and brown adipogenic potential.

The notion that brown fat and skeletal muscle are closely related in development is reinforced by many additional lines of evidence. Gene expression studies showed that brown fat precursor cells express many skeletal-muscle-specific genes41, 42. Additionally, the mitochondrial proteome of brown fat cells is more similar to that of muscle cells than to white adipocytes43. Finally, many factors, including PRDM16, EHMT1, EWS-FLI1, ZFP516, miR133 and miR-193b-365, have been shown to regulate a cell-fate decision between muscle and brown fat cells18, 39, 44–48.

PRDM16, a transcription factor that is enriched in brown fat relative to white fat and skeletal muscle, can drive the differentiation of brown fat cells when ectopically expressed in skeletal myogenic cells39. Conversely, loss of PRDM16 in isolated brown fat precursors promotes muscle differentiation39. Interestingly, the genetic loss of Prdm16 has relatively mild effects on brown fat development in vivo49, owing to compensation by related proteins, including PRDM3 (Evi1)49. EHMT1, a histone methyltransferase that physically interacts with PRDM16 and PRDM3, is required for brown fat differentiation and its deletion in mice promotes the expression of skeletal muscle transcripts in presumptive BAT44. The capacity for PRDM16 to repress muscle differentiation is completely dependent on EHMT1. These findings suggest that PRDM16, PRDM3 and maybe other related factors recruit EHMT1 to drive brown fat differentiation and block muscle commitment. Notably, ZFP516, another PRDM16-interacting partner and critical BAT regulator, is also required to suppress muscle genes during BAT development18.

The RNA-binding protein EWS-FLI1 controls the differentiation of brown fat cells versus muscle cells through a separate pathway45. EWS associates with the transcription factor YBX1 in brown fat precursors to activate the expression of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)7, a morphogen that promotes brown adipogenesis45, 50. Deletion of Ews-Fli1 from mice or isolated precursor cells blocks the development of brown fat and leads to an increased expression of muscle genes45, 50. Conversely, the loss of muscle commitment factors, including myogenin, blocks muscle differentiation and enhances BAT development51. Altogether, these results provide strong evidence that brown fat and skeletal muscle are closely related in development. However, the hierarchical cell relationships involved in the differentiation of somitic precursors into brown fat, muscle and dermal cells remain to be elucidated and will require clonal approaches.

A considerable impediment in studying the lineage commitment and development of brown fat is the paucity of molecular markers for brown fat precursor cells. Without such markers it is impossible to determine when and where mesodermal cells adopt a brown fat fate. The helix-loop-helix transcription factor EBF2 is selectively expressed in embryonic brown fat precursor cells relative to precursors of related lineages (myogenic, dermal or white adipogenic)36 and EBF2 protein accumulates in a subset of cells that lack markers of other lineages within the anterior-most somites by E12 of development36. In adipogenesis assays, Ebf2+ cells efficiently and uniquely differentiate into brown adipocytes that express UCP1 and PRDM1636. EBF2, in addition to functioning as a marker of brown fat precursor cells, has critical functions in brown fat development52 (Fig. 2). Ectopically expressing EBF2 reprograms myoblasts and fibroblasts into brown fat cells whereas deleting Ebf2 in mice severely disrupts BAT development52. Notably, EBF2 is required for establishing the brown fat characteristics of BAT, but is dispensable for adipocyte development per se52. Presumptive BAT depots of Ebf2-deleted mice contain white-like adipocytes with reduced mitochondria and UCP1 levels. Interestingly, maintenance of mature white fat cell identity requires ZFP423 which acts to suppress EBF2-function53. Future studies are needed to identify the key molecular events that function upstream and lead to activation of EBF2 expression and brown fat commitment in the somites.

Expansion of BAT depots

Cold exposure stimulates the hyperplastic expansion of BAT depots through a process that involves the proliferation and de novo differentiation of precursor cells. The stromal vascular fraction of adult BAT contains highly committed brown fat precursor cells that express EBF2 and Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα)27, 36. β-adrenergic signaling directly induces the proliferation of these precursor cells54, 55. Lineage studies demonstrate that cold-exposure activates brown fat precursor cells and induces their de novo differentiation into mature brown adipocytes56. The hyperplastic response depends on sympathetic innervation and β1-adrenergic receptor (ADRB1) function57. The molecular cues that control the balance between proliferation and differentiation of these precursors in BAT are unknown.

The formation of beige adipocytes

UCP1-expressing multilocular beige adipocytes emerge in WAT depots in response to cold and various other stimuli. Prolonged cold exposure leads to the appearance of UCP1+ adipocytes in most WAT depots of mice. However, certain depots, such as the inguinal WAT (a major subcutaneous depot in rodents), are highly susceptible to browning even with mild stimulation, whereas other depots, such as the epididymal (perigonadal) WAT of male mice are quite resistant to browning. For this reason, a majority of studies examining the mechanisms of beige fat development and function have focused on the inguinal WAT depot in mice.

In humans, there has been an important debate about whether the identified BAT depots are analogous to classic BAT or beige fat in rodents. Two groups reported that the largest BAT depot in adults, located in the supraclavicular region, has a molecular profile more similar to that of rodent beige fat than to brown fat11, 12. By contrast, Jespersen et al. found that the supraclavicular adipose expresses enriched levels of both beige and brown fat-selective genes relative to WAT, suggesting the presence of both cell types58. It should be noted that this latter study compared BAT samples from patients with thyroid disease to control abdominal WAT from a separate cohort of patients. The effect of disease as well as differences in the positional identity (anterior-posterior axis) of supraclavicular and abdominal adipose may have influenced the patterns of gene expression. Wu et al.12 used the most direct methodology to address the question in that they compared marker gene levels in FDG-PET positive BAT biopsies with that of adjacent regions of subcutaneous WAT from the same healthy individuals. Their results suggest that much of the adult human BAT identified by FDG-PET is likely to be beige fat. In support of this, human BAT has a beige fat-like morphology in that it contains clusters of multilocular UCP1-expressing cells interspersed amongst large white-like, unilocular adipocytes.

Traditional WAT depots in humans, including the abdominal subcutaneous depot and omental WAT, harbor mesenchymal stem cells, called adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), which have the capacity to activate a brown-fat-like differentiation program. These ADSC-derived adipocytes are fully competent to undergo UCP1-dependent thermogenesis in culture30, 31. However, the extent to which beige adipocytes are present or can be induced to develop within human WAT depots is unclear and poses a key question for future study.

Beige adipogenic precursor cells

Heterogeneous populations of adipogenic precursors isolated from WAT activate a brown fat-like differentiation program in response to various inducers ex vivo. For example, Schulz et al.59 showed that a subpopulation of the stromal vascular population (Sca1+ CD45− Mac1−) isolated from white fat and muscle can differentiate into UCP1-expressing adipocytes following exposure to BMP759. Thiazolidinediones (a class of synthetic PPARγ agonists) also induce a brown-fat-like program in mouse and human WAT-derived adipogenic precursor cells20, 28, 30, 31, 60. However, these studies did not address whether there are separate populations of committed white and beige adipogenic precursor cells in WAT.

Wu et al.12 examined the differentiation potential of clonal populations of adipogenic precursor cells isolated from inguinal WAT. They discovered that there are distinct populations of white and beige precursor cells that express predictive gene signatures12. The beige cell lines express very little UCP1 under basal conditions, but upregulate UCP1 to levels similar to those found in brown fat lines, after treatment with β-adrenergic agonists. By contrast, white fat cell lines show very little capacity to upregulate UCP1 expression. CD137 and TMEM26 were identified as novel beige-adipocyte-specific surface markers12. In separate studies, Ussar et al.61 identified PAT2 and P2RX5 as cell-surface markers of mouse and human brown and beige fat cells61. Antibodies that react with the extracellular regions of one or more of these proteins will hopefully enable researchers to identify and purify brown and beige fat cells from different depots and under various conditions.

The brown preadipocyte marker Ebf2 is expressed in a subset of adipogenic precursor cells from mouse inguinal WAT36 (Fig. 3a). Cold exposure increases the proportion of Ebf2+ precursor cells in the stromal vascular fraction. Although both Ebf2+ and Ebf2− precursor cells undergo adipocyte differentiation, only Ebf2+ cells activate a thermogenic program in response to rosiglitazone, suggesting that Ebf2 expression identifies the beige-fat-specific precursors in WAT. However, it remains to be determined if Ebf2+ cells can also give rise to white adipocytes in vivo under certain conditions such as aging and high fat feeding. It is possible that most adipogenic precursors in the inguinal WAT are Ebf2+ and have an intrinsic beige fate. The patchy expression of UCP1 and other thermogenic features would then depend on microenvironmental factors such as the proximity of the cells to nerve fibers. Ebf2-deficient WAT and isolated precursor cells have a drastically impaired capacity to undergo browning, showing that EBF2, in addition to marking beige fat cells, carries out a critical function in beige fat development62.

Fig. 3. Development of beige adipocytes.

(a) Possible mechanisms of beige adipocyte development in inguinal white adipose tissue (WAT). Different populations of precursors can be recruited by cold exposure or β-adrenergic signaling to differentiate into beige adipocytes. Pdgfrb+ mural cells, Myh11+ or SMA+ vascular smooth muscle cells, and Ebf2+; Pdgfrα+ adipogenic precursors have been reported to develop into beige adipocytes. EBF2, PRDM16, ZFP516 and PGC1α promote beige adipocyte differentiation. Myocardin-related transcription factor A (MRTFA) represses beige fat differentiation in smooth muscle-derived precursors. Cold-induced beige adipocytes lose the expression of UCP1 but can persist in the tissue after the cold stimulus is removed (for example, when the animals have warmed up). These de-activated beige cells have a white-like morphology but can be re-activated by an additional bout of cold or β-adrenergic signaling.

(b) In epididymal WAT, a high-fat diet can induce bipotent Pdgfrα+ precursors to differentiate into white adipocytes, whereas cold exposure or β-adrenergic stimulation induces the differentiation of these cells into beige adipocytes.

A number of studies indicate that beige adipogenic cells have an origin that is related to that of mural cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (Table S1). Long et al.63 discovered that UCP1-expressing beige adipocytes but not brown adipocytes (from BAT) express a vascular smooth muscle gene signature63. Lineage analyses shows that Myh11+ muscle cells give rise to at least a subset of beige adipocytes in response to cold exposure63, 64 (Fig. 3a). Consistent with the idea that smooth muscle-like cells have beige adipogenic potential, PRDM16-expression can drive the differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells into beige adipocytes63. Furthermore, deletion of PPARγ specifically in smooth muscle cells results in a complete loss of perivascular adipocytes that are known to have a cold-inducible beige fat profile65.

Smooth muscle actin (SMA; ACTA2), a gene expressed in perivascular and vascular smooth muscle cells, was independently identified as a general marker of adult adipose precursors66. This suggests that all white and beige adipocytes born in adults may derive from a vascular smooth muscle-like precursor. Consistent with this notion, most, if not all, cold-induced beige fat cells are marked by the developmental expression of SMA64. However, because SMA may also be expressed in mature beige adipocytes63, as well as marking mural cells, it is difficult to know if SMA+ mural cells are a major beige precursor population. Vishvanath et al.67 show that different types of precursors are recruited to undergo adipogenesis in a manner that depends on the nature and/or strength of the stimulus. Mural cells, that express Pdgfrβ and normally participate in WAT hyperplasia, undergo beige adipogenesis in response to long-term, but not acute, cold exposure67(Fig 3a). This mural cell population might overlap considerably with the Myh11+ precursor population that similarly requires a prolonged cold stimulus to undergo beige fat development.

A signaling pathway induced by BMP7 carries out a critical role in regulating beige adipocyte differentiation in SMA+ precursor cells68 (Fig. 3a). BMP7 represses RhoA signaling, which reduces the activity of the serum response factor (SRF)–myocardin-related transcription factor A (MRTFA) complex. Reduced MRTFA activity leads disassembly of the actin cytoskeleton, which facilitates the differentiation of beige adipocytes. Conversely, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) blocks beige fat differentiation at least in part by increasing the function of MRTFA and thus promoting actin polymerization into microfilaments (e.g. filamentous (F)-actin). Consistent with this model, deletion of Mrtfa or the TGFβ effector Smad3 from stromal vascular cells or mice enhances beige adipocyte differentiation68, 69.

Phenotypic plasticity of beige adipocytes

There has been much debate about whether cold-induced beige adipocytes derive directly from mature white adipocytes or arise from the de novo differentiation of adipogenic precursor cells (Fig. 3a, Table S1). As discussed above, there are competent beige fat precursors cells present in rodent and human WAT. However, several observations suggest that direct conversion of white to beige adipocytes can be a dominant mechanism of WAT browning. First, there is little change in DNA content or adipocyte number during the induction of beige fat70. Second, most beige adipocytes are derived from non-dividing cells, which makes mature adipocytes the most likely source of such cells71–73.

Adipocyte fate in response to cold exposure or β-adrenergic signaling has been examined in vivo by lineage-tracing techniques. Wang et al.74, elegantly showed that although some beige adipocytes derive from mature adipocytes, most form de novo. Using the same approaches, the Gupta lab found that cold-exposure induces the development of new beige adipocytes as well as the activation of UCP1-expression in a subset of pre-existing adipocytes53, 67. The Graff laboratory, using other genetic models, found that the large majority of cold-induced beige adipocytes originate from precursor cells rather than pre-existing adipocytes64. By contrast, Lee et al.57, reported that virtually all beige adipocytes descend directly from mature adipocytes57. Interestingly, beige adipocytes formed during cold-exposure (by whatever mechanism) lose their expression of UCP1 but can be retained in adipose tissue after warm adaption75. In the absence of stimulation, these adipocytes (which previously expressed UCP1) adopt a white-like morphology but can be induced to regain their multilocular morphology and reactivate UCP1 in response to another bout of cold exposure. This result indicates that the thermogenic phenotype of beige adipocytes is reversible and that sustained adrenergic signaling is required to maintain the thermogenic profile of beige adipocytes.

These studies demonstrate that de novo differentiation of precursors and mature adipocyte conversion both contribute to beige fat biogenesis (Fig. 3a). The relative balance between these mechanisms of beige fat induction may depend on the environmental history and/or age of the animal. Mice that previously experienced cool conditions may have incorporated more beige adipocytes into their WAT whereas mice housed at warmer temperatures (at/near thermoneutrality) may have fewer preformed beige adipocytes and thus rely more heavily on de novo differentiation. Adipocyte turnover and, hence, de novo differentiation might also be favored in older animals compared with younger ones. As originally advanced by Wu et al.12, we posit that beige adipocytes are a distinctive type of fat cells that express UCP1 and thermogenic components in the activated state and have a white fat morphology under unstimulated conditions.

How might phenotype switching in adipocytes be controlled? β-adrenergic signaling activates a variety of pathways to induce thermogenic genes in adipocytes. PGC-1α is a central transcriptional mediator of β-adrenergic signaling in adipocytes76–78. β-adrenergic agonists increase the expression levels and activity of PGC-1α in adipocytes via activation of the p38-MAPK pathway76. PGC-1α co-activates several transcription factors, including IRF4, to promote mitochondrial biogenesis and activate thermogenic genes79. Adipocyte-specific loss of Pgc-1α is associated with reduced levels of UCP1 and thermogenic capacity in WAT80. Cold exposure, in addition to activating PGC-1α in adipose, also reduces the expression of the EBF2-repressor ZFP42353.

Bi-potent precursor cells for white and beige adipocytes

Beige adipocytes develop very robustly in the inguinal WAT, which expresses higher levels of PRDM16 and other brown fat factors21. However, most WAT depots undergo browning in response to cold, especially during long-term exposure72. Even the epididymal WAT of male mice, which is considered to brown poorly, acquires UCP1+ cells in response to cold exposure. Interestingly, the mechanism for beige fat cell induction in epididymal WAT is distinct from that seen in inguinal WAT81. In epididymal WAT, PDGFRα+ precursor cells undergo proliferation after β3-adrenergic stimulation before losing PDGFRα expression and differentiating into UCP1+ beige adipocytes81. Clonal analyses shows that PDGFRα+ adipogenic cells from epididymal WAT are bipotent, as they can differentiate into both beige and white adipocytes81 (Fig. 3b). Further studies are needed to determine whether beige adipocytes in different depots or with different origins have different functions.

Cellular crosstalk within adipose tissue

Brown and beige fat contains many other cell types in addition to adipocytes, including preadipocytes, neurons, vascular endothelial cells and immune cells (Fig. 4). Crosstalk amongst these cell types has pronounced effects on the expansion and thermogenic activation of brown/beige adipose tissues.

Fig. 4. Crosstalk between brown/beige adipocytes and other adipose-resident cells.

(a) Adipocytes and nerve cells. Parenchymal sympathetic nerve fibers secrete catecholamines to regulate the development and the thermogenic function of brown/beige adipocytes. Conversely, brown/beige adipocytes might also promote nerve remodeling by producing neurotrophic factors, including nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and neuregulin 4 (NRG4).

(b) Brown/beige adipocytes and vasculature. Adipocytes secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to stimulate angiogenesis. The enhanced vasculature provides increased nutrition and oxygen to sustain thermogenesis in brown/beige adipocytes, thereby promoting energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity.

(c) Brown/beige adipocytes and immune cells. Interleukin (IL)-33 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), which secrete IL-13 and IL-5. IL-5 activates eosinophils, which produce IL-4. IL-4, in turn, induces the differentiation of M2 macrophages, which provide a critical source of catecholamines for beige fat activation. IL-4 (from eosinophils or ILC2s) also acts directly on Pdgfrα+ precursors to increase their proliferation and differentiation into beige adipocytes. Furthermore, ILC2s secrete met-enkephalin peptides to promote beige adipocyte differentiation. METRNL (Meteorin-like), secreted by muscle and adipose, activates eosinophils and type II cytokine signaling to drive beige adipocyte development.

Brown/beige adipocytes and neurons

The sympathetic nervous system is intimately involved in regulating both the development and thermogenic function of brown adipocytes82, 83 (Fig 4a). The presence of sensory neurons in BAT that are likely to participate in regulating the functions of BAT has also been documented84, 85. The importance of innervation in BAT function has been classically demonstrated through denervation studies86–88. BAT denervation leads to a large reduction in UCP1 levels, mitochondrial activity, blood flow and glucose uptake, particularly in animals exposed to the cold or given a high-fat diet. Reciprocally, treating animals with noradrenaline or synthetic β-agonists recapitulates adipose responses to cold, including brown fat activation and beige fat development. Notably, amongst WAT depots, the density of sympathetic nerve fibers correlates positively with the development of beige fat72. Moreover, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies show that chronic cold exposure increases the arborization of noradrenergic nerve fibers, providing a potential mechanism to amplify the cold-response89.

The expression of PRDM16 in adipocytes and their consequential browning leads to an increased density of nerve fibers in WAT in the absence of cold exposure21. This suggests that beige fat induction promotes nerve remodeling to allow for more efficient thermogenic activation of newly recruited beige adipocytes. Adipocyte-derived candidates that could mediate nerve branching include nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which are known regulators of nerve growth and differentiation90, 91. Neuregulin 4 (NRG4), a brown fat-secreted factor, also has a potentially important role in promoting terminal nerve branching92. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate nerve fiber branching within adipose tissue might provide new therapeutic targets to enhance energy expenditure.

One caveat to consider in the aforementioned studies is that neurons were largely identified by immunohistochemistry for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker of noradrenergic neurons and a rate limiting enzyme in catecholamine synthesis. However, adipose tissue macrophages, in addition to neurons, express TH and provide a critical source of catecholamines during cold exposure93. Thus, at least some of the TH+ cells observed in the WAT of cold-adapted animals are likely to be macrophages, and not nerve fibers.

Brown/beige adipocytes and the vasculature

Adipose tissues, especially BAT, are highly vascularized tissues3. The vasculature is also dynamically regulated in response to the metabolic demands of the tissue. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a major angiogenic factor, is expressed at higher levels in BAT relative to WAT94, 95. VEGF levels are further induced by cold exposure to stimulate the growth of blood vessels94, 96, 97, and the resulting angiogenesis provides BAT with the necessary supply of oxygen and substrate to fuel thermogenesis (Fig. 4b). Surprisingly, cold induces angiogenesis in the absence of UCP1 or hypoxia in adipose tissues, suggesting the existence of a non-canonical mechanism for increasing the expression of VEGF96. In addition to its angiogenic action, VEGF augments beige and brown fat differentiation when overexpressed in adipose tissues of mice98–101, which leads to metabolic improvements. Conversely, a high fat and high sucrose diet reduces the levels of VEGF and causes a decrease in vessel density in the BAT of mice102. This decreased density leads to mitophagy and a pronounced whitening of brown fat102. Together, these data indicate that the vascular supply profoundly regulates the thermogenic capacity and function of beige and brown fat. Related to this, the adipose tissue surrounding most blood vessels, called perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT), has thermogenic features like beige fat65, 103. PVAT secretes pro-inflammatory factors upon vascular injury104, leading to the idea that PVAT regulates endothelial function. Consistent with this, loss of PVAT reduces vascular temperature and impairs lipid clearance65. High levels of substrate oxidation and thermogenesis by PVAT might play an important role in preserving endothelial function.

Brown/beige adipocytes and immune cells

Immune cells that reside in adipose tissue have a significant role in regulating metabolic homeostasis105, 106. Obesity or a high-fat diet increases the recruitment of monocytes into adipose tissue as well as their differentiation into proinflammatory M1-like macrophages. These M1-like macrophages produce inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), which block insulin action in adipocytes, impair preadipocyte differentiation and induce brown adipocyte apoptosis107–109 (Fig. 4c). Conversely, in lean animals, anti-inflammatory M2-like macrophages produce cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10, which promote insulin sensitivity and adipocyte differentiation110 (Fig. 4c). Alternatively-activated M2-macrophages are maintained in adipose tissue via the function of eosinophils, another specialized type of immune cell population that produces the type II cytokines interleukin (lL)-4 and IL-13. Strikingly, the ablation of eosinophils and type II signaling in mice causes obesity and insulin resistance111.

Type II cytokine signaling in adipose may drive many of its beneficial effects on metabolism through brown fat activation and beige adipose tissue remodeling. Cold exposure activates eosinophils in adipose, leading to increases in IL-4 and IL-13 and the alternative activation of macrophages. Alternatively-activated macrophages enhance lipolysis, WAT browning and BAT thermogenesis via the secretion of catecholamines93 (Fig. 4c). The production of catecholamines by macrophages provides a mechanism to disseminate beige fat activation, given that WAT typically has fewer sympathetic nerve fibers than BAT. This discovery is ground breaking, as it refutes the long-held dogma that sympathetic nerve fibers are solely responsible for the cold-mediated activation of lipolysis and thermogenesis in adipocytes.

IL-4 also acts directly on adipogenic precursors in WAT to stimulate proliferation and thermogenic programming56. Loss of type II-signaling by genetic manipulation greatly reduces the development of beige fat and lowers energy expenditure112. Conversely, treatment of mice with IL-4 induces beige fat biogenesis and increases whole-animal energy expenditure to reduce obesity. Interestingly, Meteorin-like (METRNL), a protein secreted by muscle and WAT, promotes beige fat biogenesis by activating eosinophils and alternatively-activated macrophages in WAT113.

The type II immune pathway that controls brown/beige fat activation also involves additional immune populations in adipose tissue, including group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) and regulatory T cells (Tregs). ILC2s produce type II cytokines, among which is IL-5, an essential driver of eosinophil activation and survival114, 115. Adipose tissues from obese mice and humans contain fewer ILC2s than adipose tissues from lean mice. Whereas IL-33-induced activation of ILC2s or adoptive transfer of ILC2s promotes WAT browning and suppresses diet-induced obesity56, 116, deletion of IL-33 in mice (and hence reductions in the number of ILC2s causes obesity112, 116. In addition to functioning in eosinophil maintenance, ILC2s also directly promote WAT browning by producing met-enkephalin peptides, which increase the expression of UCP1 in adipocytes116, and by secreting IL-4, which stimulates the proliferation and thermogenic programming of adipogenic precursors56.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) also play a critical role in maintaining proper adipose tissue function117. Given that these cells promote alternative macrophage activation, the beneficial metabolic effects of adipose Tregs may depend on brown/beige fat activation. Interestingly,BAT harbors a distinctive class of Tregs that are required for efficient thermogenesis118. Further studies are warranted to examine the function of Tregs in beige fat formation, and the mechanism by which cold engages the type II cytokine signaling network in adipose tissues.

Conclusions and perspectives

Brown and beige fat are major thermogenic tissues in rodents that protect animals against the negative metabolic effects of a high fat diet. The correlation between the activity of brown fat and leanness in humans indicates that BAT might also influence energy balance and body weight in humans. However, whether reduced BAT activity is a cause and/or a consequence of obesity in people remains unknown. Regardless of whether the levels of brown fat activity naturally influence body weight or metabolism, increasing the amount and/or activity of brown fat in humans could be a safe and effective strategy to combat metabolic disease. In this regard, there is speculation that some of the metabolic improvements seen in patients that undergo gastric bypass procedures could be mediated by increases in brown fat119, 120. Activation of brown fat could also be used in patients that have lost weight through diet and/or exercise in order to counteract the typical decline in metabolic rate and prevent recidivism.

The renewed interest in the physiological role of BAT and its potential therapeutic application in humans has driven major discoveries in basic science focused on the development of brown/beige fat. Lineage-tracing studies have begun to clarify the origins of different types of adipocytes and have revealed lineage relationships between vascular smooth muscle and beige adipocytes, and between brown fat and skeletal muscle cells. Many powerful transcriptional regulators of brown and beige fat cell differentiation have been identified, including PRDM16, EBF2 and ZFP516. Finally, a variety of mechanisms that control brown and beige fat activation have been proposed, including a novel role for type II cytokine signaling and alternatively activated macrophages. Future studies are needed to integrate all these various pathways into a cohesive model and to determine whether some of these pathways can be manipulated therapeutically to increase brown/beige fat function.

An important area of future research concerns the biology of fat precursors, which remains enigmatic. Fortunately, novel genetic tools that can be used to manipulate and study adipogenic precursor cells in vivo are being developed. Key issues relate to how adipogenic precursors are specified and how these precursor cells are regulated under various physiological and pathological states. Another outstanding question for the field is to determine the relative roles of brown and beige fat in metabolism. Finally, brown or beige fat cells can also have beneficial effects on systemic metabolism through mechanisms beyond thermogenesis per se (Box 2). Altogether, there is great optimism that continued research into the mechanisms that control brown and beige fat biology will result in novel therapies to combat metabolic disease.

Box 2. Non-canonical functions of beige and brown fat.

Brown and beige adipose tissues might affect systemic metabolism through non-canonical mechanisms, including via the secretion of important autocrine, paracrine or endocrine factors. For example, Neuregulin 4 (NRG4) is secreted by brown fat and acts on the liver to reduce fat storage; this has beneficial effects on systemic insulin sensitivity132. Brown and beige fat also promote osteoblast activity and bone health via secreting WNT10b and IGFBP2133. Moreover, it is likely that the induction of beige fat, which is accompanied by profound WAT remodeling, leads to substantial alterations in the adipokine secretion profile which could have a wide-range of metabolic effects in multiple tissues.

Brown and beige fat also indirectly influences systemic metabolism by acting as a metabolic sink for various substrates, including glucose, triglycerides and presumably other metabolites134. Finally, the remodeling and structural changes that accompany beige fat development may improve tissue function by decreasing fibrosis, reducing hypoxia and reducing inflammatory processes. Future studies examining these and other non-canonical functions of beige and brown fat are ongoing in many laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Summary of lineage tracing studies.

Footnotes:

(a) Constitutively active lines

Several constitutively active Cre/lox mouse lines have been used: Adipoq-Cre124, 125, Fabp4-Cre125, Ucp1-Cre79, Myf5-Cre36, 39, 126, Pdgfrα-Cre/GFP36, 81, 127, Wt1-Cre122, Myh11-Cre/GFP63. This table summaries their contribution to different lineages.

(b) Inducible lineage tracing lines

This table summaries lineage tracing results using these Cre/lox mouse lines: Pax7-CreERT240, En1-CreER38, Adipoq-rTTA74,Adipoq-CreER57, 64, Ucp1-CreERT275, Acta2-CreERT264, 66, Myh11-CreER63, 64, Pdgfrα-CreERT257, 81, Pdgfrβ-rTTA128.

Key points.

Brown and beige adipocytes are thermogenic fat cells that are highly specialized to dissipate chemical energy in the form of heat. There is great hope that these cells can be targeted therapeutically to combat obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Brown adipocytes develop in distinctive developmental depots of brown adipose tissue (BAT) and have a relatively stable thermogenic phenotype. These cells are poised for heat production in response to various stimuli, including catecholamines that are secreted by sympathetic nerves in BAT upon cold exposure.

Beige adipocytes are UCP1-expressing and thermogenically-competent adipocytes that form in white adipose tissue (WAT) depots in response to various stimuli, including cold exposure or β3-adrenergic agonists. The beige phenotype of WAT is flexible and the maintenance of beige cells requires ongoing stimulation.

Beige adipocytes can arise either from: (1) adipogenic precursor cells in WAT through de novo differentiation or (2) through the direct conversion of mature unilocular white-like adipocytes.

Brown and beige fat cells express certain transcription factors, including EBF2, PRDM16, IRF4 and ZFP516 that cooperate with general adipogenic factors PPARγ and the c/EBPs to drive brown adipocyte differentiation and thermogenic gene programing. ZFP423 acts in white adipocytes to suppress EBF2 and maintain white fat fate.

Type 2 cytokine signaling and alternative macrophage activation plays a critical role in regulating both brown fat thermogenesis and beige fat biogenesis. Alternatively activated macrophages secrete catecholamines in WAT to promote browning.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship to W.W. and NIDDK grant 5R01DK10300802 to P.S.

Proposed glossary terms

- Adaptive thermogenesis

Facultative process by which animals produce heat only in response to stimuli, such as cold-exposure or high fat diet. Muscle shivering and uncoupled respiration in brown/beige fat are major mechanisms

- Adipokine

Cytokine or other protein secreted by adipocytes

- β-oxidation

Process by which fatty acids are metabolized in the mitochondria into Acetyl-CoA which enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for the generation of ATP

- Catecholamine

Class of naturally occurring chemicals that act as neurotransmitters including noradrenaline and adrenaline

- Dermomyotome

Mesodermal domain of the somite that is fated to differentiate into the skeletal muscle (myotome) and dermis (dermatome)

- Eosinophil

Specialized type of white blood cell characterized by granules that contain histamine and other chemical mediators and play an important role in anti-parasite immunity

- Helix-loop-helix transcription factor

Transcription factor family characterized by a structural motif. These factors are known to play important roles in various developmental processes

- Homeobox gene

Family of genes that encode for proteins characterized by a DNA sequence called the homeobox. Members of this gene family play critical roles in patterning and morphogenesis

- FTO locus

Encodes the FTO (Fat mass and obesity-associated) gene for which certain variants have been strongly associated with obesity in Humans

- Lipolysis

Hydrolysis of lipids into component free fatty acids and glycerol

- M1 macrophage

Macrophage populations that have a pro-inflammatory profile and are characterized by secretion of Interferon-γ, TNFα and Interleukin-1

- M2 macrophage

Alternatively activated macrophage populations that are characterized by secretion of Arginase and Interleukin-10 and play important roles in tissue repair and homeostasis

- Met-Enkephalin (Met-Enk)

Type of Enkephalin, which is a five amino acid peptide that classically known to regulate nocioception by binding to Opioid receptors. Met-Enk contains Methionine whereas the other Enkephalin contains Leucine (Leu-Enk)

- Mural cell

Cell closely associated with the vasculature, typically a vascular smooth muscle cell or pericyte

- Noradrenaline

Neurotransmitter in the catecholamine family that is secreted by sympathetic neurons to stimulate various responses, including adaptive thermogenesis in brown/beige fat

- Thiazoledinediones (TZDs)

Class of synthetic high affinity agonists for the nuclear hormone receptor, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). TZDs improve Insulin-action in mice and humans via activation of PPARγ in adipocytes and other cell types

- TRAP (Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification) technology

Method enabling immunopurification of polysomes and associated mRNA that are being actively transcribed

Biographies

Patrick Seale obtained his Ph.D. in Biology from McMaster University, Canada in the laboratory of Dr. Michael Rudnicki. He trained as a postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Bruce Spiegelman at Harvard Medical School where he focused on the development of brown and beige fat cells. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of Pennsylvania. His laboratory in the Institute for Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism investigates molecular mechanisms that control the fate and function of adipose tissues during normal development and in disease states.

Wenshan Wang obtained her PhD at Tsinghua University where she studied genetic pathways involved in lipid metabolism. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, where her work focuses on signals regulating the early stage of brown/beige precursor commitment and differentiation.

References

- 1.Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell. 2012;151:400–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao Y. Adipose tissue angiogenesis as a therapeutic target for obesity and metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:107–15. doi: 10.1038/nrd3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat Med. 2013;19:1252–63. doi: 10.1038/nm.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cypess AM, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito M, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1526–31. doi: 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virtanen KA, et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1518–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E444–52. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cypess AM, et al. Anatomical localization, gene expression profiling and functional characterization of adult human neck brown fat. Nat Med. 2013;19:635–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jespersen NZ, et al. A classical brown adipose tissue mRNA signature partly overlaps with brite in the supraclavicular region of adult humans. Cell Metab. 2013;17:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharp LZ, et al. Human BAT possesses molecular signatures that resemble beige/brite cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. Wu et al. demonstrate that beige adipocytes are a distinctive cell type that has a different molecular signature from classic brown fat or white fat cells. Importantly, human BAT depots are identified as having a beige rather than a brown fat profile. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enerback S, et al. Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature. 1997;387:90–4. doi: 10.1038/387090a0. Enerback et al demonstrate that UCP1 is genetically required for cold-induced adaptive thermogenesis and cold-tolerance in mice. The Ucp1-null mice generated in this study have been widely studied in many laboratories around the world. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. A role for brown adipose tissue in diet-induced thermogenesis. Nature. 1979;281:31–35. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldmann HM, Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 2009;9:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowell BB, et al. Development of obesity in transgenic mice after genetic ablation of brown adipose tissue. Nature. 1993;366:740–2. doi: 10.1038/366740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cederberg A, et al. FOXC2 is a winged helix gene that counteracts obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and diet-induced insulin resistance. Cell. 2001;106:563–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempersmier J, et al. Cold-inducible Zfp516 activates UCP1 transcription to promote browning of white fat and development of brown fat. Mol Cell. 2015;57:235–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopecky J, Clarke G, Enerback S, Spiegelman B, Kozak LP. Expression of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein gene from the aP2 gene promoter prevents genetic obesity. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2914–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI118363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiang L, et al. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Ppargamma. Cell. 2012;150:620–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seale P, et al. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:96–105. doi: 10.1172/JCI44271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanford KI, et al. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 123:215–223. doi: 10.1172/JCI62308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1500–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cypess AM, et al. Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a beta3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell Metab. 2015;21:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.009. This study reports that human BAT thermogenesis can be pharmacoligcally stimulated by a β3-andrenergic agonist and that this increases energy expenditure. This is important proof-of-concept that BAT-targeted therapies could be a promising approach to reduce metabolic disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoneshiro T, et al. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3404–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI67803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claussnitzer M, et al. FTO Obesity Variant Circuitry and Adipocyte Browning in Humans. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:895–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klaus S, Ely M, Encke D, Heldmaier G. Functional assessment of white and brown adipocyte development and energy metabolism in cell culture. Dissociation of terminal differentiation and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 10):3171–80. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.10.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohno H, Shinoda K, Spiegelman BM, Kajimura S. PPARgamma agonists induce a white-to-brown fat conversion through stabilization of PRDM16 protein. Cell Metab. 2012;15:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrovic N, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Thermogenically competent nonadrenergic recruitment in brown preadipocytes by a PPARgamma agonist. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E287–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00035.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartesaghi S, et al. Thermogenic Activity of UCP1 in Human White Fat-Derived Beige Adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29:130–9. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elabd C, et al. Human multipotent adipose-derived stem cells differentiate into functional brown adipocytes. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2753–60. doi: 10.1002/stem.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue B, et al. Genetic variability affects the development of brown adipocytes in white fat but not in interscapular brown fat. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:41–51. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600287-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Bolze F, Fromme T, Klingenspor M. Intrinsic differences in BRITE adipogenesis of primary adipocytes from two different mouse strains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:1345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerra C, Koza RA, Yamashita H, Walsh K, Kozak LP. Emergence of brown adipocytes in white fat in mice is under genetic control. Effects on body weight and adiposity. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:412–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI3155. Important study showing that there is large mouse strain-dependent variation in the induction of beige adipocytes with relatively little effect on classical BAT. Additionally, beige fat levels amongst inbred and recombinant strains were highly correlated with the ability of β3-agonism to decrease body weight. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kazak L, et al. A Creatine-Driven Substrate Cycle Enhances Energy Expenditure and Thermogenesis in Beige Fat. Cell. 2015;163:643–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.035. This study identifies a novel mechanism for UCP1-independent thermogenesis in beige adipocytes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, et al. Ebf2 is a selective marker of brown and beige adipogenic precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:14466–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412685111. The helix-loop-helix transcription factor EBF2 is identified as a specific marker gene/protein and functional regulator of brown and beige fat precursor cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lidell ME, et al. Evidence for two types of brown adipose tissue in humans. Nat Med. 2013;19:631–4. doi: 10.1038/nm.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atit R, et al. Beta-catenin activation is necessary and sufficient to specify the dorsal dermal fate in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2006;296:164–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seale P, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454:961–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. This study shows that brown adipocytes and muscle have a common or similar origin in development. PRDM16 was identified as a transcriptional factor that drives brown fat differentiation and suppresses muscle differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lepper C, Fan CM. Inducible lineage tracing of Pax7-descendant cells reveals embryonic origin of adult satellite cells. Genesis. 2010;48:424–36. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walden TB, Timmons JA, Keller P, Nedergaard J, Cannon B. Distinct expression of muscle-specific MicroRNAs (myomirs) in brown adipocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:444–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Timmons JA, et al. Myogenic gene expression signature establishes that brown and white adipocytes originate from distinct cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4401–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610615104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forner F, et al. Proteome differences between brown and white fat mitochondria reveal specialized metabolic functions. Cell Metab. 2009;10:324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohno H, Shinoda K, Ohyama K, Sharp LZ, Kajimura S. EHMT1 controls brown adipose cell fate and thermogenesis through the PRDM16 complex. Nature. 2013;504:163–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park JH, et al. A multifunctional protein, EWS, is essential for early brown fat lineage determination. Dev Cell. 2013;26:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trajkovski M, Ahmed K, Esau CC, Stoffel M. MyomiR-133 regulates brown fat differentiation through Prdm16. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1330–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin H, et al. MicroRNA-133 controls brown adipose determination in skeletal muscle satellite cells by targeting Prdm16. Cell Metab. 2013;17:210–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun L, et al. Mir193b-365 is essential for brown fat differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:958–965. doi: 10.1038/ncb2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harms MJ, et al. Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab. 2014;19:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseng YH, et al. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454:1000–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nabeshima Y, et al. Myogenin gene disruption results in perinatal lethality because of severe muscle defect. Nature. 1993;364:532–5. doi: 10.1038/364532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajakumari S, et al. EBF2 determines and maintains brown adipocyte identity. Cell Metab. 2013;17:562–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shao M, et al. Zfp423 Maintains White Adipocyte Identity through Suppression of the Beige Cell Thermogenic Gene Program. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1167–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bukowiecki L, Collet AJ, Follea N, Guay G, Jahjah L. Brown adipose tissue hyperplasia: a fundamental mechanism of adaptation to cold and hyperphagia. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:E353–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1982.242.6.E353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bronnikov G, Houstek J, Nedergaard J. Beta-adrenergic, cAMP-mediated stimulation of proliferation of brown fat cells in primary culture. Mediation via beta 1 but not via beta 3 adrenoceptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2006–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee MW, et al. Activated type 2 innate lymphoid cells regulate beige fat biogenesis. Cell. 2015;160:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee YH, Petkova AP, Konkar AA, Granneman JG. Cellular origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes in adult mice. FASEB J. 2015;29:286–99. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-263038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jespersen NZ, et al. A classical brown adipose tissue mRNA signature partly overlaps with brite in the supraclavicular region of adult humans. Cell metabolism. 2013;17:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schulz TJ, et al. Identification of inducible brown adipocyte progenitors residing in skeletal muscle and white fat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:143–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010929108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petrovic N, et al. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7153–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ussar S, et al. ASC-1, PAT2 and P2RX5 are cell surface markers for white, beige, and brown adipocytes. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:247ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stine RR, et al. EBF2 promotes the recruitment of beige adipocytes in white adipose tissue. Molecular Metabolism. 2016;5:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Long JZ, et al. A smooth muscle-like origin for beige adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2014;19:810–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berry DC, Jiang Y, Graff JM. Mouse strains to study cold-inducible beige progenitors and beige adipocyte formation and function. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10184. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang L, et al. Loss of perivascular adipose tissue on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma deletion in smooth muscle cells impairs intravascular thermoregulation and enhances atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2012;126:1067–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.104489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang Y, Berry DC, Tang W, Graff JM. Independent stem cell lineages regulate adipose organogenesis and adipose homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1007–22. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vishvanath L, et al. Pdgfrbeta+ Mural Preadipocytes Contribute to Adipocyte Hyperplasia Induced by High-Fat-Diet Feeding and Prolonged Cold Exposure in Adult Mice. Cell Metab. 2016;23:350–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McDonald ME, et al. Myocardin-related transcription factor A regulates conversion of progenitors to beige adipocytes. Cell. 2015;160:105–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.005. This study reports that BMP7 promotes beige adipogenesis and suppresses smooth muscle programming in mesenchymal stem cells by regulating ROCK signaling and reducing the activity of MRTFa, a transcription factor. Genetic loss of Mrtfa in mice enhances beige adipocyte differentiaiton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yadav H, et al. Protection from obesity and diabetes by blockade of TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling. Cell Metab. 2011;14:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghorbani M, Himms-Hagen J. Appearance of brown adipocytes in white adipose tissue during CL 316,243-induced reversal of obesity and diabetes in Zucker fa/fa rats. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:465–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Himms-Hagen J, et al. Multilocular fat cells in WAT of CL-316243-treated rats derive directly from white adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C670–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vitali A, et al. The adipose organ of obesity-prone C57BL/6J mice is composed of mixed white and brown adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:619–29. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M018846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barbatelli G, et al. The emergence of cold-induced brown adipocytes in mouse white fat depots is determined predominantly by white to brown adipocyte transdifferentiation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E1244–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00600.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, Scherer PE. Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat Med. 2013;19:1338–44. doi: 10.1038/nm.3324. Wang et al develop a genetic system in mice to examine the fate of mature adipocytes in vivo, called AdipoChaser. A key result in this paper is that the majority of cold-induced beige adipocytes in inguinal WAT do not arise from pre-existing mature fat cells in the tissue. This suggests that de novo differentiation of resident precursor cells is the main mechansim of beige fat formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosenwald M, Perdikari A, Rulicke T, Wolfrum C. Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:659–67. doi: 10.1038/ncb2740. This study reports that beige adipocytes lose Ucp1 expression and become lipid-replete white adipocyte-like cells after warm adaptation. These cells can be re-activated to regain their multilocular beige phenotype and UCP1-expression after another round of cold stimulation, demonstrating the phenotypic plasticity of beige adipocytes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cao W, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3057–67. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.3057-3067.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Puigserver P, et al. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Uldry M, et al. Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 2006;3:333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kong X, et al. IRF4 is a key thermogenic transcriptional partner of PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2014;158:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kleiner S, et al. Development of insulin resistance in mice lacking PGC-1alpha in adipose tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9635–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207287109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee YH, Petkova AP, Mottillo EP, Granneman JG. In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by beta3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 2012;15:480–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bartness TJ, Shrestha YB, Vaughan CH, Schwartz GJ, Song CK. Sensory and sympathetic nervous system control of white adipose tissue lipolysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;318:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morrison SF, Madden CJ, Tupone D. Central control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ryu V, Garretson JT, Liu Y, Vaughan CH, Bartness TJ. Brown adipose tissue has sympathetic-sensory feedback circuits. J Neurosci. 2015;35:2181–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3306-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vaughan CH, Bartness TJ. Anterograde transneuronal viral tract tracing reveals central sensory circuits from brown fat and sensory denervation alters its thermogenic responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R1049–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00640.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. Effects of denervating brown adipose tissue on the responses to cold, hyperphagia and noradrenaline treatment in the rat. J Physiol. 1984;355:457–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silva JE, Larsen PR. Adrenergic activation of triiodothyronine production in brown adipose tissue. Nature. 1983;305:712–3. doi: 10.1038/305712a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takahashi A, Shimazu T, Maruyama Y. Importance of sympathetic nerves for the stimulatory effect of cold exposure on glucose utilization in brown adipose tissue. Jpn J Physiol. 1992;42:653–64. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.42.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]