Abstract

Patient: Female, 78

Final Diagnosis: Adrenal pseudocyst

Symptoms: None

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Operation

Specialty: Urology

Objective:

Mistake in diagnosis

Background:

Adrenal pseudocysts are often discovered incidentally on imaging, but the diagnosis and treatment can be challenging. A case of adrenal pseudocyst with hemorrhage is presented that mimicked a solid tumor on imaging, resulting in adrenalectomy.

Case Report:

A 78-year-old woman was found to have a right adrenal lesion on abdominal imaging. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a heterogeneously enhanced mass, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a high-intensity T1-weighted and T2-weighed image, with an irregular enhanced margin. The imaging findings were suggestive of a solid tumor of the adrenal gland. Although full endocrine serological studies were negative, the lesion increased in size at two-year follow-up. Right laparoscopic adrenalectomy was performed, and a benign hemorrhagic adrenal pseudocyst was diagnosed histologically.

Conclusions:

Adrenal pseudocyst can be associated with acute intracystic hemorrhage, and imaging will show contrast enhancement, suggesting malignancy. In such cases, surgical excision is both diagnostic and curative.

MeSH Keywords: Adrenal Gland Diseases, Diagnosis, Therapeutics

Background

Small adrenal pseudocysts are commonly detected incidentally by ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen [1]. Larger adrenal pseudocysts may present with pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, or as palpable masses [1]. The adrenal gland is a common site for primary and metastatic tumors. However, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish adrenal pseudocysts from adrenal tumors by imaging studies when they are associated with hemorrhage. Areas of hemorrhage are enhanced by the imaging contrast medium, and hematomas may contain components that mimic solid tumors [2]. Therefore, it may be difficult to decide upon the optimal treatment approach, and surgical excision may be required to exclude malignancy. We report a case of an adrenal pseudocyst that presented as an enlarging mass on imaging, which was surgically resected laparoscopically.

Case Report

A 78-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a right lateral abdominal mass. She had a history of hypertension and cerebral infarction and had been taking warfarin. There was no history of trauma or malignancy; she did not smoke or consume alcohol.

Serological studies, including an endocrine screen, were negative. Serum and urinary catecholamines and metanephrines were normal. Aldosterone and cortisol were also within normal limits. However, protein induced by vitamin K absence/antagonist-II (PIVKA-II), also known as des-gamma carboxyprothrombin (DCP), which is an abnormal form prothrombin, was elevated at 17,700 mAU/ml, which was thought to be due to warfarin treatment.

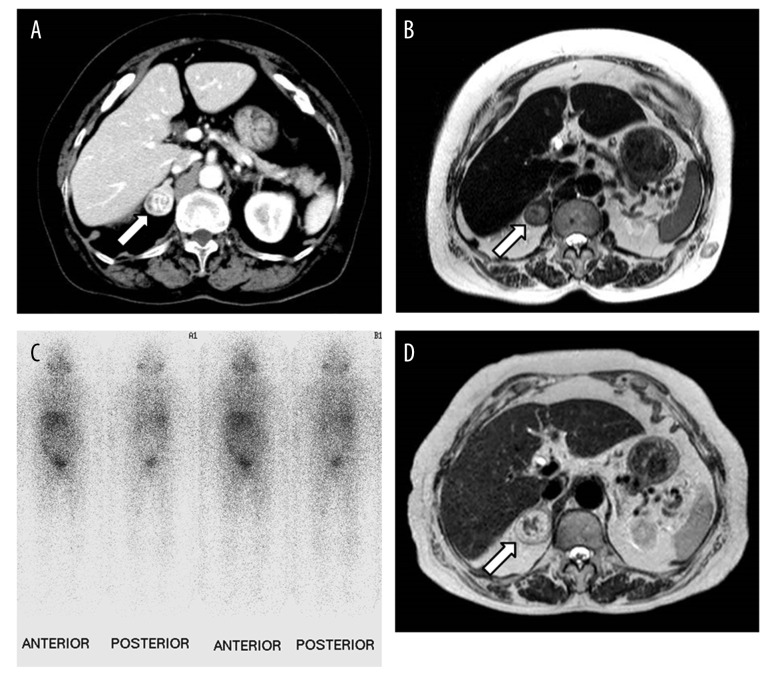

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed due to initial suspicion of a diagnosis of a liver tumor. Although imaging failed to identify any remarkable findings in the liver, a round-shaped heterogeneous mass, measuring 2.4 cm in diameter, with an area of high density, was identified in the right adrenal gland (Figure 1A). The adrenal lesion showed high intensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1B). The adrenal lesion had a thickened wall with non-uniform contrast enhancement and an irregular margin. No lymphadenopathy was seen. Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy was negative (Figure 1C). Based on the imaging findings, the adrenal lesion was suspected to be a solid tumor. Because there was no initial evidence that the lesion was a functioning adrenal tumor, the patient was followed-up without surgical intervention.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy. (A) An axial image from intravenous contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showing a heterogeneously hyperdense and solid mass in the left adrenal gland. (B) An axial T2-weighted MRI image shows a heterogeneously high signal intensity of the adrenal cystic lesion (arrow), which is 24 mm in diameter. (C) MIBG scintigraphy was negative. (D) An axial T2-weighted MRI image at six-month follow-up shows that the lesion increased in size to 32 mm in diameter.

MRI was performed at two-year follow-up, at which time, the right adrenal lesion was found to have increased in size to 3.2 cm in diameter (Figure 1D). Because a malignant tumor was a possible diagnosis, we performed laparoscopic right adrenalectomy. No adhesions to the surrounding tissue were present, and the operative time was 149 min with minimal blood loss. The adrenal mass and the surrounding fatty tissue were resected en bloc.

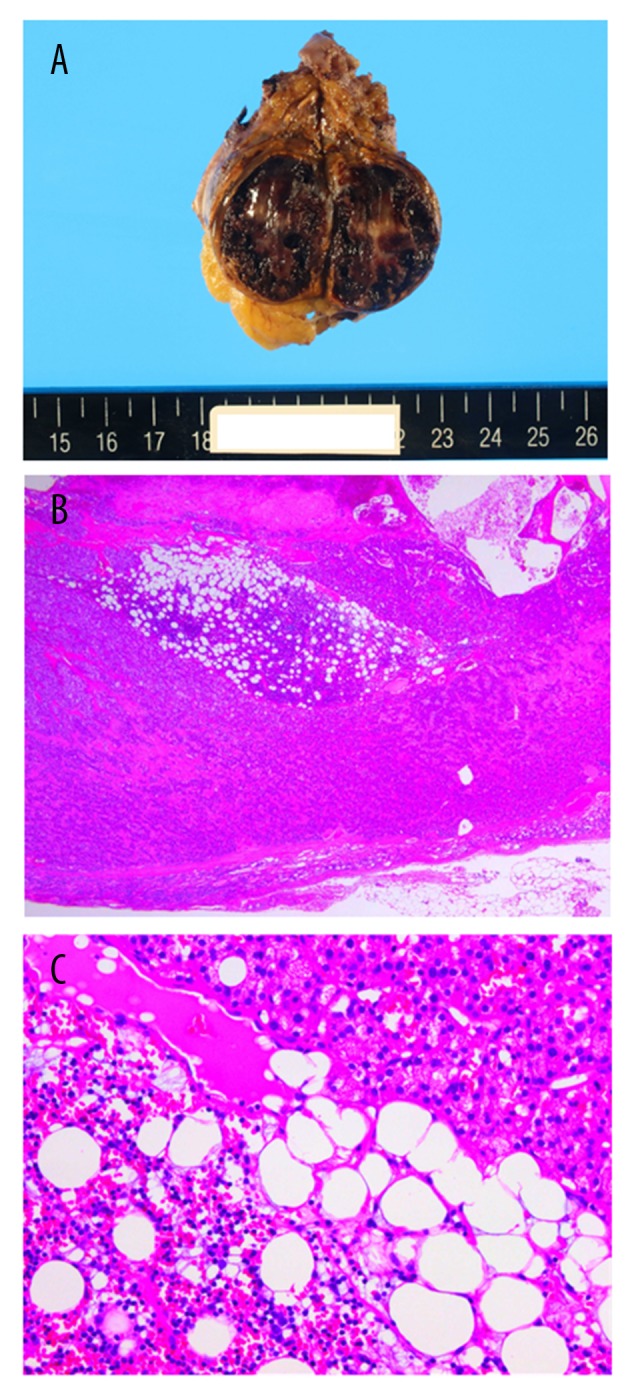

The resected mass showed a dark red appearance (Figure 2A). Histologically, the main contents of the mass were fresh blood and fibrin-rich exudate with chronic inflammation (Figure 2B). In areas, the excised mass had a cystic wall but without a cell lining. The diagnosis was a benign adrenal pseudocyst due to hemorrhage (Figure 2C) [3]. There was no evidence of malignancy.

Figure 2.

Pathology of the adrenal pseudocyst. (A) Macroscopic appearance of the surgically resected specimen showed a 3.2-cm-diameter solid component with hemorrhagic areas. (B) Photomicrograph of the histology of a section of the excised mass showing acute inflammation and hemorrhage into the lumen of the cyst. (Magnification ×20). (C) Photomicrograph of the histology of a section of the hemorrhagic pseudocyst. (Magnification ×200).

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course, and she remained asymptomatic with no recurrence on CT imaging, six months following laparoscopic adrenalectomy.

Discussion

Cysts of the adrenal gland have been classified into four major types: parasitic cysts (7%), epithelial cysts (9%), endothelial cysts (45%), and adrenal pseudocysts (39%) [3]. The possible etiology of adrenal pseudocysts include hemorrhage into the adrenal parenchyma following stress, including birth, trauma, surgery, or coagulopathy [3, 4]. Kyoda et al. reported that two of three patients with adrenal hemorrhagic pseudocysts had coagulopathy due to treatment with anti-platelet agents or anticoagulants [4].

In this case report, administration of warfarin may have been the cause of hemorrhagic pseudocyst formation. Unlike true cysts, adrenal pseudocysts have no cellular lining but are composed of fibrous tissue, sometimes with calcification [5]. When the lumen of the adrenal pseudocyst contains blood, attenuated adrenal gland tissue is often present in the cyst wall [6]. Some variants of adrenal pseudocyst have been reported to contain lesions with myelolipomatous metaplasia [3].

Cystic adrenal lesions are often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. The reported incidence of adrenal pseudocyst is increasing due to the increasing use of imaging methods, including as ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as in this case [7]. On CT and MRI, adrenal pseudocysts classically present as homogeneous cystic lesions, with low attenuation on CT imaging, which may be hypo-intense on T1-weighted imaging, and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging [7]. Complex pseudocysts may appear more heterogeneous on imaging and may also demonstrate areas of central calcification [7]. In this case, the T1-weighted image on MRI showed high intensity, probably due to hemorrhage.

The differential diagnosis of adrenal pseudocysts includes epithelial cysts, endothelial cysts, and parasitic cysts [8]. A definitive preoperative diagnosis of adrenal pseudocyst can be difficult to make when there is acute intracystic hemorrhage, as in the present case, as this results in contrast enhancement on imaging. The solid appearance of hemorrhagic adrenal pseudocyst can mimic pheochromocytoma, myelolipoma, metastatic malignancy, primary adrenal adenoma, and adrenocortical carcinomas [2,9,10].

The diagnosis of hemorrhagic adrenal pseudocyst should be made with caution on imaging alone because between 7% and 44% of such lesions prove to be tumors at surgery [11]. It is important to distinguish adrenal malignancy from nontumoral hemorrhage. Certain features raise the suspicion of malignancy within a cystic adrenal lesion, including a heterogeneous appearance on imaging and the presence of necrosis in the center of the mass accompanied by calcification, and the size of the adrenal mass [12,13]. Adrenal tumors ≥5 cm on cross-sectional imaging are more likely to be malignant, and the risk of malignancy in adrenal pseudocysts ≥5 cm is approximately 7%, rising with increased size [14]. However, it has been reported that adrenal lesions <4 cm in diameter can also be malignant [15]. Some studies have recommended that in patients with adrenal lesions <4 cm, a repeat CT several months later is indicated, to determine any increase in size [16]. In this case, the tumor was imaged again at follow-up, because the size of the tumor was <4 cm. The tumor was finally resected because it increased in size.

Recognition and diagnosis of a primary adrenocortical carcinoma at an early stage are particularly important because complete resection offers the only chance of patient survival [17]. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is a useful imaging modality in cases of suspected malignancy because this imaging method shows hypermetabolic activity at the site of the hemorrhage. However, the diagnosis of nonfunctional adrenocortical carcinomas using FDG-PET is sometimes difficult because adrenal hematomas can also avidly take up fluorodeoxyglucose [18]. Histopathological diagnosis by adrenal biopsy is also difficult because the distinction between adrenal hyperplasia, adenoma, and carcinoma cannot typically be made on a limited biopsy specimen [19,20].

Small, asymptomatic and nonfunctional adrenal pseudocysts are often followed clinically without intervention if the patient is clinically stable and there is no evidence of malignancy [21]. However, careful follow-up or even resection may be required, even if the mass is clinically benign and can be managed conservatively.

In the present case, the tumor was resected because it had gradually grown in size during the follow-up period. When adrenal tumors are suspected of harboring malignancy, there is controversy regarding the role of laparoscopic surgery for the resection of the tumors. Porpiglia and colleagues have reported that laparoscopic and open approaches in patients with stage I and II adrenocortical carcinomas are comparable in terms of clinical patient outcomes [22]. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in our case because pre-operative imaging showed that the margin of the tumor was smooth and there was no suspicion of invasion into the surrounding tissues.

Conclusions

Adrenal pseudocyst can be associated with acute intracystic hemorrhage, and imaging will show contrast enhancement, suggesting malignancy. In such cases, surgical excision is both diagnostic and curative.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Erickson LA, Lloyd RV, Hartman R, Thompson G. Cystic adrenal neoplasms. Cancer. 2004;101:1537–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacerdote MG, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. CT of the adrenal gland: the many faces of adrenal hemorrhage. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s10140-011-0989-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernest E. Tumors of the Adrenal Glands and Extra-adrenal Paraganglia – Volume 8 (Afip Atlas of Tumor Pathology Series 4) 2007:185–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyoda Y, Tanaka T, Maeda T, et al. Adrenal hemorrhagic pseudocyst as the differential diagnosis of pheochromocytoma – a review of the clinical features in cases with radiographically diagnosed pheochromocytoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36:707–11. doi: 10.3275/8928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew SP, Sim R, Teoh TA, Low CH. Haemorrhage into non-functioning adrenal cysts-report of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999;28:863–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medeiros LJ, Lewandrowsui KB, Vickery AL. Adrenal pseudocyst: A clinical and pathological study of eight cases. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:660–65. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang LS, Wong YC, Chan CJ, Chu SH. Imaging spectrum of adrenal pseudocyst on CT. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:531–35. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patnaik S, Htut A, Wang P, et al. All those liver masses are not necessarily from the liver: A case of a giant adrenal pseudocyst mimicking a hepatic cyst. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:333–37. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.893798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Ernst RD, et al. Imaging of nontraumatic hemorrhage of the adrenal gland. Radiographics. 1999;19:949–63. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.4.g99jl13949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bovio S, Porpiglia F, Bollito E, et al. Adrenal pseudocyst mimicking cancer: A case report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30:256–58. doi: 10.1007/BF03347435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wedmid A, Palese M. Diagnosis and treatment of the adrenal cyst. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s11934-009-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan E, Poder L, Courtier J, et al. Imaging of nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W91–98. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Fishman EK, et al. Spectrum of CT findings in non-malignant disease of the adrenal gland. Radiographics. 1998;18:393–412. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasperlik-Zaluska AA, Otto M, Cichocki A, et al. 1,161 patients with adrenal incidentalomas: indications for surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:121–26. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yip L, Tublin ME, Falcone JA. The adrenal mass: Correlation of histopathology with imaging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:846–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passoni S, Regusci L, Peloni G, et al. A giant adrenal pseudocyst mimicking an adrenal cancer: Case report and review of the literature. Urol Int. 2013;91:245–58. doi: 10.1159/000346754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilimoria KY, Shen WT, Elaraj D, et al. Adrenocortical carcinoma in the United States: treatment utilization and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2008;113:3130–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Repco BM, Tulchinsky M. Increased F-18 FDG uptake in resolving atraumatic bilateral adrenal hemorrhage (hematoma) on PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:651–53. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181813179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diolombi ML, Khani F, Epstein JI. Diagnostic dilemmas in enlarged and diffusely hemorrhagic adrenal glands. Hum Pathol. 2016;53:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson M, Fanning DM, Moloney J, Flood H. Giant adrenal pseudocyst harbouring adrenocortical cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4169. pii: bcr0520114169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fassnacht M, Kroiss M, Allolio B. Update in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4551–64. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porpiglia F, Fiori C, Daffara F, et al. Retrospective evaluation of the outcome of open versus laparoscopic adrenalectomy for stage I and II adrenocortical cancer. Eur Urol. 2010;57:873–78. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]