Abstract

Premise of the study:

Chloroplast primers were developed from genomic data for the taxonomically challenging genus Castilleja. We further tested the broader utility of these primers across Orobanchaceae, identifying a core set of chloroplast primers amplifying across the clade.

Methods and Results:

Using a combination of three low-coverage Castilleja genomes and sequence data from 12 Castilleja plastomes, 76 primer combinations were specifically designed and tested for Castilleja. The primers targeted the most variable portions of the plastome and were validated for their applicability across the clade. Of these, 38 primer combinations were subsequently evaluated in silico and then validated across other major clades in Orobanchaceae.

Conclusions:

These results demonstrate the utility of these primers, not only across Castilleja, but for other clades in Orobanchaceae—particularly hemiparasitic lineages—and will contribute to future phylogenetic studies of this important clade of parasitic plants.

Keywords: Castilleja, chloroplast, hemiparasite, high-throughput sequencing, microfluidic PCR, Orobanchaceae

The plastome is heavily relied upon in plant systematics, owing to its conserved nature and orthology, particularly for the study of deeper evolutionary divergences. Moreover, discordance between the uniparentally inherited plastome and the biparentally inherited nuclear genome may provide insights into introgression events and their direction (Twyford and Ennos, 2012). However, the low rate of molecular evolution in the plastome can become a hindrance when reconstructing relationships between closely related taxa, requiring large amounts of data to resolve these relationships (Uribe-Convers et al., 2016). In an attempt to alleviate this problem, several recent studies have leveraged available high-throughput sequencing data for the development of variable taxon-specific plastid (and nuclear) regions (e.g., Uribe-Convers et al., 2016).

Castilleja L. (Orobanchaceae; “the paintbrushes”) is a taxonomically challenging clade that includes ∼200 hemiparasitic species, many of which have a complicated history of polyploidy and/or hybridization (Heckard and Chuang, 1977). Microsatellite markers have been developed in Castilleja for population genetic studies (Fant et al., 2013), and broader, genus-wide phylogenetic reconstructions within Castilleja used two chloroplast regions (trnL-F and the rps16 intron), nuclear ribosomal spacers (ITS and ETS), and a low-copy nuclear gene (waxy) (Tank and Olmstead, 2008, 2009). However, species-level relationships lacked resolution in Tank and Olmstead (2008, 2009), limiting conclusions regarding diversification and hybridization. Here, we follow Uribe-Convers et al. (2016) for primer design and validation of the most highly variable chloroplast regions in Castilleja. Because these primers were designed for the Fluidigm Access Array microfluidic PCR system (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, California, USA), annealing temperature specifications are consistent across all primer combinations; this allows for parallelization of PCR and is ideal for high-throughput sequencing platforms (see Uribe-Convers et al., 2016 for application of this approach). Although our initial focus was the development of Castilleja-specific primers, we evaluated their utility in silico in three other lineages of Orobanchaceae to obtain a subset of “core” chloroplast primers with the potential to amplify across the clade. Once identified, we surveyed this set of core primers to assess their performance using additional sampling across Orobanchaceae. Orobanchaceae represents the largest parasitic clade of angiosperms and has well-documented modifications to the plastome, such as reduction and accelerated rates of molecular evolution; however, the most comprehensive phylogenetic investigation to date was based on only five gene regions (McNeal et al., 2013). Thus, an expanded molecular toolkit will be of great benefit for future investigations in the clade.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Three species of Castilleja were selected for genome skimming (C. cusickii Greenm., C. foliolosa Hook. & Arn., C. tenuis (A. Heller) T. I. Chuang & Heckard; Appendix 1), with taxa chosen to include both annual and perennial lineages (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] Sequence Read Archive [SRA] accession SRP100222). DNA extraction, purification, Illumina library construction, and subsequent cleaning of reads followed Uribe-Convers et al. (2016). Samples were sequenced as 100-bp single-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA) at the University of Oregon, and cleaned reads were assembled against a reference genome (Sesamum indicum L. JN637766) using the Alignreads pipeline version 2.25 (Straub et al., 2011). In addition to these three low-coverage genomes, we also used existing data for 12 Castilleja plastomes generated by Uribe-Convers et al. (2014) using a long-PCR approach. Fifteen plastomes in total were aligned using MAFFT version 7.017b under the default settings (Katoh and Standley, 2013).

We used a custom R script (Uribe-Convers et al., 2016) to identify the most variable regions of the alignment spanning 400–1000 bp that were flanked by conserved regions, enabling prioritization based on predicted amplicon size and variability. Regions containing ambiguous bases were discarded, and those missing from one or more taxa in the alignment, particularly in the plastomes generated through the long-PCR method, were given lesser priority. We used Primer3 (Untergasser et al., 2012) to design primer pairs for the selected regions with an annealing temperature of 60°C (±1°C), and allowing no more than three continuous nucleotides of the same base, following the specifications of the Fluidigm Access Array System protocol.

We validated each primer combination using PCR with three high-quality Castilleja DNA isolations chosen to represent major lineages, sensu Tank and Olmstead (2008) (C. lineariloba (Benth.) T. I. Chuang & Heckard, C. lemmonii A. Gray, and C. pumila Wedd.; Appendix 1), but different than those selected for genome skimming and primer design, and a negative control. Because we followed the approach of Uribe-Convers et al. (2016), it was necessary for our validation conditions to simulate the four-primer reaction of the Fluidigm microfluidic PCR using a standard thermocycler. Therefore, our target-specific primers include a 5′ conserved sequence (CS) tag, obtained from the Fluidigm Access Array System protocol, which provides an annealing site for Illumina sequencing adapters and sample-specific barcodes. PCR amplification followed Uribe-Convers et al. (2016), and amplicons were visualized on a standard agarose gel. In total, 76 primer combinations were successfully designed and validated (Table 1).

Table 1.

All primer pair sequences designed for Castilleja (names and region amplified), amplicon lengths, and validation results for Orobanchaceae and outgroup taxon Paulownia. All pairs were designed for an annealing temperature of 60°C (±1°C). Combinations are listed from most variable to least variable, according to our prioritization scheme (see text). Boldfaced rows correspond to core Orobanchaceae primers, defined by successful amplification in two or more major clades in Orobanchaceae (see Fig. 1).

| Locus (Region) | Primer sequences (5′–3′)a | Amplicon length (bp)b | Clade I: Lindenbergia sp.c | Clade II: Schwalbea americanac | Clade III: Orobanche californicac | Clade IV: Castilleja lineariloba, C. pumila, C. lemmoniid | Clade IV: Lamourouxia virgatae | Clade IV: Pedicularis sp.c | Clade V: Neobartsia filiformise | Clade V: Rhinanthus alectorolophusc | Clade VI: Harveya purpureac | Clade VI: Physocalyx majore | Paulowniaceae: Paulownia elongatac (outgroup) |

| Cas_120561_F_Cas_121371_R (ndhl-ndhG) | F: GTCCAAACGATCCCATACCAR: TTTAGGTCGGTTACCGGTGT | 810 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_111970_F_Cas_112789_R (ndhF-ycf1) | F: GGTGGAAAGTGAGGAAGAAAGAR: TCAAGAAGGAACAGGTTTGGA | 819 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_129331_F_Cas_130126_R (ycf1) | F: TGAGTTTAATCAACCCGGAGAR: GACCCTTTCCTGAACAAATCA | 795 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_112854_F_Cas_113746_R (ndhF) | F: ACATAGTATTGTCCGATTCATAAGGAR: GGAGGGACCCACTCCTATTT | 892 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_126859_F_Cas_127713_R (ycf1) | F: GAACGGATCCAAGATCTCCTCR: GGCGAAATGCGCTTCATA | 854 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_59866_F_ Cas_60624_R (accD) | F: TTGCCGTCAAAGACATTCGR: GCCTGTTTGAACAGCCTCAG | 758 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cas_127891_F_Cas_128420_R (ycf1) | F: GGATTCCTTGATAGTGAAGAACAGAR: GAAGGATCTGGACGATCGAA | 529 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_130168_F_Cas_130760_R (ndhF-ycf1) | F: ACAACCGAGTCCTTGTTTCAAR: GGTGGAAAGTGAGGAAGAAAGA | 592 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_126110_F_Cas_126868_R (ycf1) | F: TTCTAATCGATAATTAGGCCAAAGAR: GGATCCGTTCTATCACAACCA | 758 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_32159_F_ Cas_32745_R (psbM-trnE) | F: AATCGGATCAATATCATGAATAACAAR: ATTCGCCAATCTACCACGAG | 586 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cas_77140_F_ Cas_78034_R (psbH-petB) | F: TGTCGCAATGGCTCTATTTGR: TCATCTCGTACAGCTCAAGCA | 894 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_10778_F_ Cas_11525_R (rps16-trnG) | F: TCAGTTTGATGATCCTTTGATGAR: CATTCGGCTCCTTTATGGAA | 747 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_46472_F_ Cas_47162_R (ycf3-rps4) | F: GGGAACTATTCCGATTTCATTGR: CTAACTGGTGGAATAAAGGTCTCC | 690 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_47758_F_ Cas_48638_R (rps4-trnL) | F: CGGCGATACGGACGTATTTAR: GAATTGTGATCAAGAAATCGAAATTA | 880 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_17609_F_ Cas_18412_R (rps2-rpoC2) | F: ACACTCTCGCAGAGCCGTATR: CCACGATAGACCAGAACAATCA | 803 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_33546_F_ Cas_34499_R (trnT-psbD) | F: GACTCGTTTGGGAATTAAATCAAR: CTTCAACCATTTCCGAGCAC | 953 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_67504_F_ Cas_68343_R (psbE-petL) | F: TTGTACCGAGGGCATCTTTAGR: AACCGAAATAACTCGTTATAGTAAGCA | 839 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_72399_F_ Cas_73245_R (rps12-clpP) | F: GGGCTGGTTTAGATTGATCCTR: TTTCATTGGATTATGTATCGAGAGAG | 846 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_62840_F_ Cas_63772_R (ycf4-cemA) | F: ATTCCGTTGACCCGTACTGAR: AAGAGAGAAATCCACCAAGGTAAA | 932 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cas_65707_F_ Cas_66634_R (petA-psbJ) | F: CTCGGGAAATCCCTTGTACCR: TCCGGATTAGGTTCATCCCTA | 927 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_69456_F_ Cas_70174_R (trnP-rpl33) | F: CAACTCTAAGCGACCCTTAAATACAR: TACTCGCGCATCTTTCCTCT | 718 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_4537_F_ Cas_5319_R (matK) | F: GGTTCCTTGACCAACCACAGR: ATCCCAACAACACGACTTCC | 782 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_48611_F_ Cas_49520_R (trnT-trnL) | F: TGTAATTTCGATTTCTTGATCACAATR: CAGATACAGATTTGGGCCATC | 909 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_29425_F_ Cas_30291_R (rpoB-petN) | F: TTGAAGCGAAGTAGGATAATTTGAR: TCCTACCAGAGGCTACAATCTGA | 866 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_125001_F Cas_125859_R (rps15-ndhH) | F: AAATAATCCCAACGCGTTACAR: AATGTTTCAATTAGCTCTCGAAATG | 858 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_21290_F_ Cas_22036_R (rpoC2) | F: TGTTCTGATTCTACATATTGATCGTTTR: CGTGAAGGGCTTTCTTTAACA | 746 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_20851_F_ Cas_21307_R (trnG-atpA) | F: CTGGTAGAGAGTGGTCGGATCTR: GGTTGAATTGGGAGAAGCTG | 456 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_11589_F_ Cas_12461_R (trnG-atpA) | F: AGCCTTCCAAGCTAACGATGR: CTGGAATCAGACCCGCTATT | 872 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_47139_F_ Cas_47689_R (trnS-rps4) | F: GGAGACCTTTATTCCACCAGTTAGR: TTTCGATTGGGTATGGCTTC | 550 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_14073_F_ Cas_14724_R (atpF intron) | F: TTCGATTCATTTGGCTCTCAR: TGGAAAGGGAGTGTGTGTGA | 651 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_122476_F_Cas_123331_R (ndhA intron) | F: ACGGCTCCTCATAGGTCACAR: TGCTGTTAAAGGAATTCAATCTCA | 797 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_73947_F_ Cas_74498_R (clpP) | F: TCTTGTTCCTGAATGGGTCTCR: GTTACGTTTCCACATCAAAGTGA | 551 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_123306_F_Cas_124104_R (ndhH-ndhA) | F: AATGAGATTGAATTCCTTTAACAGCR: TGAAATTGGCTGATATTATGACG | 798 | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Cas_24256_F_ Cas_25037_R (rpoC1) | F: ATAAACCGCGTAATCGCAAGR: TGTCATCCCAGTCAATCCAA | 781 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_85769_F_ Cas_86417_R (rpl22) | F: CATCAGGATATACCATAGTTGCCTTTR: CCATACGATTGCCGTTCATA | 648 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_36699_F_ Cas_37444_R (psbC-psbZ) | F: GCGGTCCGCAGAATATATGAR: TTATTTCACAAATGGGAATCCTG | 745 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_61880_F_ Cas_62831_R (psaI-ycf4) | F: GCAATGGCTTCTTTATTTCTTCAR: GGCCTCGGATGTCCATATAA | 951 | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Cas_71554_F_ Cas_72431_R (rpl20-rps12) | F: TCCAATGGCTTCGGCTACTAR: AATCATCCGGTTAGGATCAATCT | 877 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_5508_F_ Cas_6230_R (trnK-rps16) | F: CCCATTCATTTCCTTTAATTCGR: TTAGCTCAACAGTTTGATTAGCTTG | 722 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_13394_F_ Cas_14062_R (atpA-atpF) | F: CGAGCAATACCATCGCCTACR: TTGGTTCGGGAAGGGATTAT | 668 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_19198_F_ Cas_19976_R (rpoC2) | F: TCCTGGAGTGGCCAAATAAGR: CCTTTGTTGAAATAAGGGCAAA | 778 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Cas_124082_F_Cas_124968_R (ndhH) | F: CGTCATAATATCAGCCAATTTCAR: ATGGACCCGAACGACTAGG | 886 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_52327_F_ Cas_52920_R (ndhC-trnV) | F: TCGATAAATACAGATACACCCAATACAR: GCAAGAATCCTAGGCGAAGA | 593 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_50548_F_ Cas_51414_R (trnF-ndhJ) | F: TCGGTTCAGATACAAATAAATCCAR: AGGGTCATTTGTCTGCTTGG | 866 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_27800_F_ Cas_28512_R (rpoB) | F: CCGCTACAGAACGAATACGCR: GTATCCGCGGGATTAATTTG | 712 | X | X | |||||||||

| Cas_20009_F_ Cas_20813_R (rpoC2) | F: TTGTCTTGGTCCCAATTCAATACR: TCATCATTCCACTCCAATCG | 804 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Cas_14705_F_ Cas_15624_R (atpH) | F: TCACACACACTCCCTTTCCAR: GATATCGAAGTAGTTCGGATTAGTCA | 919 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cas_25017_F_ Cas_25720_R (rpoC1-rpoB) | F: TTGGATTGACTGGGATGACAR: TATTAGAGCGCGCCAAGAAG | 703 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cas_40118_F_ Cas_40881_R (psaB) | F: TCCTGCGATATATTGGTGATGAR: CAATTGGTTTACGCACTAATGAA | 763 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cas_44810_F_ Cas_45699_R (ycf3) | F: ACACCGCTGCTCAAGACTTTR: CCATCGAAGGTTGTTGAAGTG | 889 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cas_121734_F_ Cas_122486_R (ndhA-ndhI) | F: CCTGGCAGCTCGTATTGTTTR: TGAGGAGCCGTATGAGGTAAA | 752 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cas_93851_F_ Cas_94660_R (ycf2) | F: CGGAGCTGGAACTGCTAACTR: GTCCGGGTAGAGACCAAAGA | 749 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cas_54595_F_ Cas_55457_R (trnM-atpB) | F: GGGAGTCATTGGTTCAAATCCR: GCGTTTCTTATCACAACCCTTT | 862 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_94709_F_ Cas_95300_R (ycf2) | F: CGGATCTAGTTCATGGCCTATTR: TCTGCAAATAATTCTCGATGTGA | 591 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cas_70574_F_ Cas_71412_R (rps18-rpl20) | F: GGATCGAATTGATTATAGAAACATGAR: AGCTCGGAGACGTAGAACAAA | 838 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cas_78484_F_ Cas_79253_R (petB-petD) | F: CCTTACCTCGGGACCAAATCR: CAATGCAGAGGAAATGAATGC | 769 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cas_80388_F_ Cas_81242_R (rpoA) | F: TTTCTAGACTGCCCAATATCTGTTTR: AAGCCGACACAATAGGCATT | 854 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cas_81995_F_ Cas_82887_R (rpl36-rps8) | F: CCGCTACAGAACGAATACGCR: GTATCCGCGGGATTAATTTG | 892 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cas_85146_F_ Cas_85791_R (rps3-rpl22) | F: TCCGAACTGTATAGGAACAATAATCAR: GGCAACTATGGTATATCCTGATGTG | 645 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Cas_96241_F_ Cas_97030_R (ycf1-ndhB) | F: TCCGAGATCTCTTATTGAATTGCR: TTCCATCGAATTGAGTATGATTGT | 789 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_38180_F_ Cas_38949_R (trnG-rps14) | F: CCGCCCAAGATCAAGATAAAR: ACCTGAACCATTATGGCAAGA | 769 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cas_21932_F_ Cas_22735_R (rpoC2-rpoC1) | F: CGCGTGAGATATCCAGCATR: TCTCAGGCCTGTTCATATGGT | 803 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cas_12567_F_ Cas_13399_R (atpA) | F: AGGCGGTCATACTTCCTTCAR: TGCTCGTATTCACGGTCTTG | 832 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cas_25855_F_ Cas_26657_R (rpoB) | F: GCATAATGTCCACTGGAACGR: AAGGCCCTGAAAGGATCACTA | 802 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cas_64793_F_ Cas_65732_R (petA-psbJ) | F: TAAGCCCGTGGATATTGAGGR: AAATGCGGTACAAGGGATTTC | 939 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_23417_F_ Cas_24195_R (rpoC1) | F: TTCCTGAAGTATTTCCCATACAATCR: CGATACATTTCGCAATCGAG | 778 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cas_66623_F_ Cas_67525_R (psbJ-petL) | F: ACCTAATCCGGAATATGAACCAR: TCTAAAGATGCCCTCGGTACA | 902 | X | ||||||||||

| Cas_90084_F_ Cas_90885_R (ycf2) | F: AGAATCAGACCTATTCCCGAAAR: TGCCTCCATTATGTTGTTGC | 801 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_18394_F_ Cas_19186_R (rpoC2) | F: TTGTTCTGGTCTATCGTGGAAAR: TGGCCATTATGGAGAAATCC | 792 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_42062_F_ Cas_42897_R (psaA) | F: GGGCTAAAGCGTGGGTATTTR: TCAGGTGCATGTATCTTTACCG | 835 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cas_92095_F_ Cas_92935_R (ycf2) | F: CCAAGTCGATACGATCCATTCR: TCGGTGCAGATGTAGGATACC | 840 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cas_87589_F_ Cas_88512_R (rpl2-rpl23) | F: TTGCTGCCGTTACTCTTCAGR: ACGAATCGGTGTGGTATATTCA | 923 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cas_26951_F_ Cas_27708_R (rpoB) | F: CTCCATTCCCTGAGACAAGGR: CCGACTCCTCAGAATTTGGT | 757 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cas_91056_F_ Cas_91895_R (ycf2) | F: AATGAAATATACGATCAACCAACATTR: TCATAATTATTGATACGGGCCTTT | 839 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Cas_104111_F_Cas_104945_R (trnL-rrn16) | F: TTGGTTTGACACTGCTTCACAR: ATTTCACGCTCTTCCTTTCG | 834 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cas_34914_F_ Cas_35729_R (psbD-psbC) | F: GAGCTTGCTCGATCTGTTCAR: ATTGCTCCAGCCCAGAATAC | 815 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Primer sequence for the “Castilleja-specific primer.” To make the target-specific primer for subsequent microfluidic PCR, conserved sequence tags CS1 (5′-ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA) and CS2 (5′-TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT) were added to each forward and reverse primer, respectively.

Amplicon length (bp) estimated from Castilleja plastome alignments.

PCR validations using DNAs from Bennett and Mathews (2006).

PCR validations were considered successful for Castilleja when amplification occurred for all three taxa, representing one annual lineage (C. lineariloba) and two perennial lineages (C. pumila and C. lemmonii).

Taxa that both were PCR validated and had primer combinations evaluated in silico against their respective plastome assemblies (raw read files available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive submission SRP100222).

To test the broader utility of our Castilleja-specific primers, we searched for matches in two published plastome assemblies for Lamourouxia virgata Kunth (Pedicularideae, Clade IV; Fig. 1) and Neobartsia stricta (Kunth) Uribe-Convers & Tank (Rhinantheae, Clade V) (NCBI SRA accessions SRR1023133 and SRR1023130, respectively; Uribe-Convers et al., 2014). We assembled the plastome for a third taxon, Physocalyx major Mart. (Buchnereae, Clade VI; NCBI SRA accession SRP100222), to include in our comparison. Physocalyx major was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 at the University of Oregon as 100-bp paired-end reads. Cleaned reads for P. major were mapped to three reference plastomes with one copy of the inverted repeat region removed (Sesamum indicum JN637766, Neobartsia inaequalis (Benth.) Uribe-Convers & Tank KF922718, Castilleja paramensis F. González & Pabón-Mora KT959111) using Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Consensus sequences of the resultant contigs were obtained and used as final references. Contigs were then imported into Geneious R7 version 7.0.6 (Kearse et al., 2012), and a consensus sequence was obtained by calling regions with less than 5× coverage as “N” and using the “Highest Quality” as a threshold.

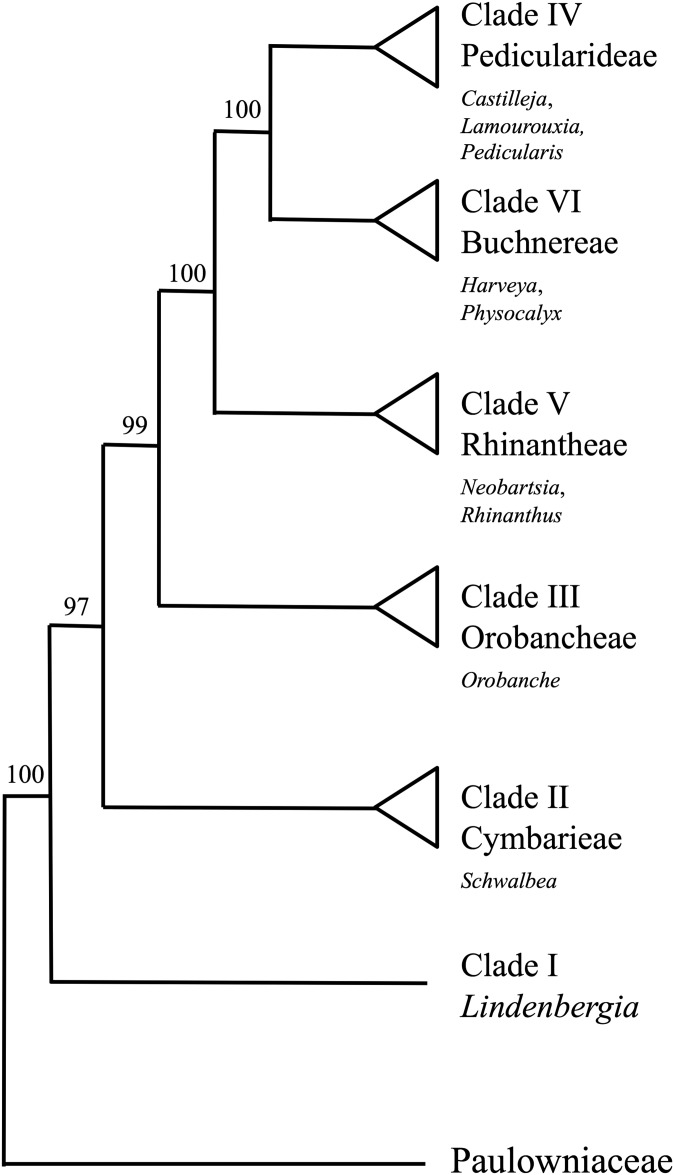

Fig. 1.

Relationships among major clades within Orobanchaceae modified from McNeal et al. (2013), with taxa used for primer validation indicated (see text). Bootstrap support values for clades are indicated along the branches and follow McNeal et al. (2013).

Separate BLAST databases were created for Lamourouxia Kunth, Neobartsia Uribe-Convers & Tank, and Physocalyx Pohl assemblies (-makeblastdb), and blastn_short was used to search for matching hits with the list of Castilleja chloroplast primers. Hits were further considered if both primer pairs (1) occurred on the same contig and (2) had predicted amplicon sizes between 350–1000 bp. Once we obtained a set of primer hits for the three taxa, they were validated with PCR using L. virgata, P. major, and Neobartsia filiformis (Wedd.) Uribe-Convers & Tank (Appendix 1), as described above. Primer pairs with amplification in at least two out of three taxa above were chosen for another round of PCR validation with expanded taxon sampling that represented all major lineages of Orobanchaceae (sensu McNeal et al., 2013; Appendix 1): Lindenbergia sp. Lehm. (Clade I), Schwalbea americana L. (Cymbarieae, Clade II), Orobanche californica Cham. & Schltdl. (Orobancheae, Clade III), Pedicularis sp. L. (Pedicularideae, Clade IV), Rhinanthus alectorolophus (Scop.) Pollich (Rhinantheae, Clade V), Harveya purpurea Harv. (Buchnereae, Clade VI), and Paulownia Siebold & Zucc. (Paulowniaceae; outgroup). As a positive control, we included CS-tagged “universal” primers for the trnL-F region (“trn-c” and “trn-f” of Taberlet et al., 1991, in Tank and Olmstead, 2008).

Out of the 76 primer pairs designed and validated for Castilleja, we identified 36 pairs with applicability across Orobanchaceae (referred to as core Orobanchaceae primers; these are boldfaced in Table 1). These were chosen based on amplification across a large phylogenetic breadth of the clade, but allowing for some failures. For example, Orobanche, a holoparasite, failed for most primer combinations, a result that is likely due to the reduction and modification of the plastome in this lineage (see Bennett and Mathews, 2006). Higher success rates were noted for hemiparasites.

CONCLUSIONS

We report 76 primer pairs designed to target the most variable regions of the chloroplast genome in Castilleja. We further demonstrate their utility across other major clades in Orobanchaceae, particularly with hemiparasitic taxa, and present a subset of 38 core Orobanchaceae primers. Although these primer combinations target similar highly variable plastid regions as in other angiosperm-wide studies (e.g., Ebert and Peakall, 2009), few of the primers reported here overlap directly with them. Two exceptions are Cas_11589 F (trnG) and Cas_61880 F (psaI) (Table 1), which were also developed by Ebert and Peakall (2009). Notably, our primer combinations were designed with the same annealing temperature to take advantage of the Fluidigm microfluidic PCR system and high-throughput sequencing platforms, but will also be useful for traditional PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Appendix 1.

Voucher information for species used in this study.

| Species | Voucher accession no. (Herbarium)a | Collection locality | Geographic coordinates |

| Castilleja cusickii Greenm. | Tank 2009-01 (ID) | Idaho, USA | 45.884241°N, 116.230195°W |

| Castilleja foliolosa Hook. & Arn. | A. Colwell 03-09 (YM) | California, USA | 35.3926°N, 120.3522°W |

| Castilleja lemmonii A. Gray | Jacobs 2015-088 (ID) | California, USA | 37.907982°N, 119.258583°W |

| Castilleja lineariloba (Benth.) T. I. Chuang & Heckard | Tank 2002-04 (WTU) | California, USA | 37.41387°N, 120.10833°W |

| Castilleja pumila Wedd. | Uribe-Convers 2011-120 (ID) | La Libertad, Peru | 7.99506°S, 78.44197°W |

| Castilleja tenuis (A. Heller) T. I. Chuang & Heckard | Tank 2001-13 (WTU) | Washington, USA | 46.118133°N, 121.5158°W |

| Harveya purpurea Harv. | Randle 79 (OS) | NA | NA |

| Lamourouxia virgata Kunth | Mejia 581 (CAS) | Chiapas, Mexico | 16.713611°N, 92.614722°W |

| Lindenbergia sp. Kunth | Armstrong 1163 (ISU) | NA | NA |

| Neobartsia filiformis (Wedd.) Uribe-Convers & Tank | Uribe-Convers 13-027 (ID) | La Paz, Bolivia | 16.32796°S, 67.9457°W |

| Orobanche californica Cham. & Schltdl. | Bennett 72 (A) | Cultivated | Cultivated |

| Paulownia elongata Siebold & Zucc. | s.n. (A) | Cultivated | Cultivated (https://sheffields.com) |

| Pedicularis sp. L. | Krajsek and Bennett s.n. (A) | NA | NA |

| Physocalyx major Mart. | G. O. Romão 2528 (ESA) | Minas Gerais, Brazil | 19.2635°S, 43.5508°W |

| Rhinanthus alectorolophus (Scop.) Pollich | Bennett 85 (A) | NA | NA |

| Schwalbea americana L. | Kirkman s.n. (PAC) | NA | NA |

Note: NA = not available.

Herbarium acronyms are per Index Herbariorum (http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bennett J. R., Mathews S. 2006. Phylogeny of the parasitic plant family Orobanchaceae inferred from phytochrome A. American Journal of Botany 93: 1039–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D., Peakall R. 2009. A new set of universal de novo sequencing primers for extensive coverage of noncoding chloroplast DNA: New opportunities for phylogenetic studies and cpSSR discovery. Molecular Ecology Resources 9: 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fant J. B., Wolf-Weinberg H., Tank D. C., Skogen K. A. 2013. Characterization of microsatellite loci in Castilleja sessiliflora and transferability to 24 Castilleja species (Orobanchaceae). Applications in Plant Sciences 1: 1200564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckard L. H., Chuang T.-I. 1977. Chromosome numbers, polyploidy, and hybridization in Castilleja (Scrophulariaceae) of the Great Basin and Rocky Mountains. Brittonia 29: 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. 2013. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., Buxton S., et al. 2012. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal J. R., Bennett J. R., Wolfe A. D., Mathews S. 2013. Phylogeny and origins of holoparasitism in Orobanchaceae. American Journal of Botany 100: 971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub S. C. K., Fishbein M., Livshultz T., Foster Z., Parks M., Weitemier K., Cronn R. C., Liston A. 2011. Building a model: Developing genomic resources for common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) with low-coverage genome sequencing. BMC Genomics 12: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank D. C., Olmstead R. G. 2008. From annuals to perennials: Phylogeny of subtribe Castillejinae (Orobanchaceae). American Journal of Botany 95: 608–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank D. C., Olmstead R. G. 2009. The evolutionary origin of a second radiation of annual Castilleja (Orobanchaceae) species in South America: The role of long distance dispersal and allopolyploidy. American Journal of Botany 96: 1907–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twyford A. D., Ennos R. A. 2012. Next-generation hybridization and introgression. Heredity 108: 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., Remm M., Rozen S. G. 2012. Primer3–New capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Research 40: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe-Convers S., Duke J. R., Moore M. J., Tank D. C. 2014. A long-PCR based method for chloroplast genome enrichment and phylogenomics in angiosperms. Applications in Plant Sciences 2: 1300063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe-Convers S., Settles M. L., Tank D. C. 2016. A phylogenomic approach based on PCR target enrichment and high throughput sequencing: Resolving the diversity within the South American species of Bartsia L. (Orobanchaceae). PLoS ONE 11: e0148203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]