CASE PRESENTATION

A 22-year-old African-American woman who has been dialysis dependent for four months due to hypertensive kidney disease is referred for kidney transplantation evaluation. Due to the recent occlusion of her left forearm arteriovenous graft, she is currently being dialyzed via a right internal jugular tunneled catheter. Her medications include methyldopa 250 mg bid, Tums 1000 mg with each meal and erythropoietin with dialysis. The patient is single without children, unemployed and lives with her 38 year old mother. She does not smoke or drink. Her review of systems is unremarkable. On physical exam, her weight is 284 pounds, height is 5 feet 2 inches and her body mass index is 51.9 kg/m2. The blood pressure is 130/80 and the cardiac and pulmonary exams are unremarkable. The surgeon feels she is otherwise a good candidate for transplantation except she must lose weight before being listed. What advice should she be given regarding weight loss?

Index words: obesity, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, weight loss, bariatric surgery

Introduction

This review addresses the identification and management of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who may benefit from weight loss with lifestyle, pharmacologic and surgical therapies. Due to the existing controversy regarding obesity and mortality in this population, we have provided an overview of the definition of overweight and obesity in the general population and a discussion of the potential analytic problems in observational studies which try to determine body mass index (BMI) thresholds for mortality in populations with CKD. All adults will benefit from a healthy life style regardless of kidney disease. Data also suggest that obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2 or waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women) adults with CKD who are not receiving dialysis will benefit from weight loss. For stable patients receiving dialysis, weight loss should be prescribed for those persons who would otherwise be eligible for transplantation except for their degree of obesity. Otherwise, a more individualized approach is needed for the dialysis dependent patient and clinicians should evaluate the nutritional needs along with co-morbid conditions to determine the potential benefits. Multi-disciplinary approaches are most effective for weight loss in any patient, but if medical and nutritional interventions fail, bariatric surgery performed by an experienced surgeon at a certified center may be considered for the morbidly obese adult. Studies are urgently needed to determine safe approaches for effective and sustained weight loss in adults with CKD.

Overview of Body Mass Index and Mortality in the General Population

In the U.S. and most developed countries, the obesity epidemic substantially threatens the progress in health outcomes made over the past several decades,(1) and will likely lead to a growth in the number of adults with CKD. Compared to adults with a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2, adults with BMI > 35 kg/m2 have a 7-fold increased odds of being diagnosed with diabetes and a 6-fold increased odds of being hypertensive,(2) the two most common risk factors for CKD. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies reported that 24.2% and 33.9% of kidney disease among men and women, respectively, may be attributed to overweight and obesity in the U.S.(3) Although these effects are largely mediated by the development of diabetes and hypertension, increased fat mass itself may have independent effects on CKD incidence and its progression.(4)

During the early part of the last century, life insurance companies were astute to the fact that obesity increases mortality. Until recently, the current standards used to classify “normal” or ideal weight, overweight and obesity were largely based on Metropolitan Life Insurance Company weight for height tables created from demographic data from adults who purchased life insurance from years 1935 to 1954.(5) Groups of individuals not likely to purchase life insurance during this time period were not well represented, including non-white adults and those with chronic medical conditions precluding life insurance eligibility.(6) Starting in 1995, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services dietary guidelines suggested a BMI cut-point of ≥ 25 kg/m2 for defining overweight for men and women, but conceded the lack of credible evidence for a precise threshold and wide confidence intervals for increased mortality.(5, 7) These thresholds have largely been replaced by criteria published by the World Health Organization in 1997 which defined overweight as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and included criteria for obesity stages I (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2), II (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2), and III (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2).(8)(Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification Scheme of Adult Underweight, Overweight and Obesity

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.5 |

| Ideal weight | 18.5–24.9 |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 |

| Obese | ≥ 30.0 |

| Class I | 30.0–34.9 |

| Class II | 35.0–39.9 |

| Class III | ≥ 40 |

Adapted from: Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation on obesity, Geneva, June 3–5, 1997. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1998

Although a particular BMI threshold is currently utilized to define overweight and obesity for all individuals,(5) it remains a disputatious issue whether specific BMI cut-points are appropriate for assessing cardiovascular and mortality risk for all age (9, 10) and racial/ethnic groups.(11–14) Studies have consistently demonstrated that obesity at a young age or during mid-life decreases life-expectancy.(15–17) However, the association between BMI and mortality among older adults may not mirror the associations among middle-aged or young adults.(13) A meta-analysis of studies limited to adults age ≥65 concluded that a wide range of BMI levels show no association with mortality in this group. In fact, mortality risk does not appear to rise significantly until BMI exceeds 31 kg/m2.(18) In addition to age, the association between mortality and BMI appears to also be modified by race/ethnicity.(9, 16, 19, 20)

Waist circumference as a predictor of mortality in the general population

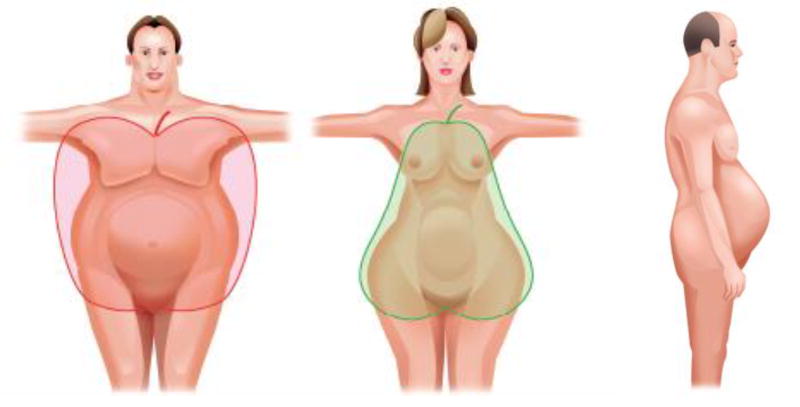

Use of BMI as a proxy for degree of adiposity has become a routine part of clinical care. However, BMI reflects both fat-free mass and fat mass and does not provide information on body composition. Figure 1 demonstrates how body fat may be preferentially distributed around the abdominal area or the hip area while some adults have an ideal BMI in the setting of abdominal obesity (Figure 1). Abdominal fat remains a strong predictor of mortality after adjustment for total body fat. (21) Thus, the adverse effects of abdominal fat largely mediate the increased cardiovascular risk associated with obesity. Abdominal fat can be best measured directly using DXA scans, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging, but waist circumference can be measured reliably without cost and correlates highly with abdominal fat.(22–24) In the general population, adults with abdominal obesity, defined as waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women, are more likely to have hypertension, diabetes, and increased cholesterol levels compared to those with a waist circumference below these thresholds regardless of presence of normal weight, overweight or class I obesity.(25, 26) These waist circumference cut-points were selected from reference values associated with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 among adults living in Scotland.(27) Although lower waist circumference thresholds may be appropriate for certain racial/ethnic groups such as Chinese or Japanese adults(28), abdominal obesity, as defined by increased waist circumference, increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality regardless of BMI, age-group, and race/ethnicity.(26, 29, 30)

Figure 1.

Cartoon depicting truncal (middle) and abdominal obesity (far left and right)

Adiposity Measures and Mortality in Adults with CKD

Obesity and abdominal obesity are common among adults with CKD and likely play a causal role for kidney disease incidence and progression. (31–35) However, it remains unclear whether higher BMI increases mortality risk in this population. Among adults with CKD, waist circumference correlates highly with abdominal fat (36) and may outperform BMI for prediction of future cardiovascular events and mortality. Elsayed et al pooled data from the Atherosclerosis in Communities (ARIC) Study and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) to examine the association between adiposity measures (BMI and waist/hip ratio) and mortality among adults with CKD.(37) CHS participants were 65 years and older at the baseline visit while the ARIC study recruited adults between the ages of 45 to 64. A total of 1669 participants with CKD, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) 15 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, were included in the analysis and the primary outcome was myocardial infarction or cardiovascular death. After a mean follow-up of 9.3 years, no significant association was noted between overweight or obesity and cardiac events when compared to an ideal BMI (20–24.9 kg/m2). In contrast, the highest waist/hip ratio (≥ 1.02 and 0.96 in men and women, respectively) had a 36% higher relative risk of cardiac events (95% CI 1.02, 1.85) compared to the group with the lowest waist/hip ratio (≤ 0.95 and 0.87 in men and women, respectively).(37) An additional analysis limited to ARIC Study participants with CKD showed that higher BMI among individuals with BMI in the “normal” range was associated with lower risk of mortality.(38) In contrast, no association was noted between BMI and mortality among participants with CKD and a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2.(38) Madero et al. reported no association between sex-specific BMI quartiles and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality after a median follow-up period of 10 years among 1759 participants of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study.(39) The mean age of these adults with CKD was 51 years and mean GFR was 39 +/− 21 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Adiposity Measures and Mortality Among Patients Receiving Dialysis

The issue of obesity among patients receiving dialysis presents a difficult dilemma. While obese dialysis patients face obstacles for transplantation, observational studies suggest that higher BMI is associated with improved survival in this population.(40–44) One of the largest studies, which included over 400,000 dialysis patients who initiated dialysis from 1995 to 2000, noted substantial and significant differences in overall survival by BMI groups after a median follow-up of 2 years. The unadjusted annual cardiovascular mortality rate was approximately two-fold higher among patients with BMI < 22 kg/m2 compared to those with BMI ≥ 37 kg/m2 and the all-cause mortality rate was over two-fold higher among patients with BMI < 19 kg/m2 vs. ≥ 37 kg/m2.(42) Prevalence of reported congestive heart failure was similar across BMI groups, but ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, previous stroke and tobacco use were all lowest in the group with a BMI ≥ 37 kg/m2. After adjustment for these factors, BMI categories starting at a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, including the highest BMI category (≥ 37 kg/m2) were associated with decreased mortality compared to BMI 22 to < 25 kg/m2. In contrast, BMI < 22 kg/m2 was associated with the highest mortality risk.(42) When the investigators limited the analysis to incident dialysis patients who had previously received a transplant, a potentially healthier group compared to the entire ESRD population, increased mortality was noted among those with BMI < 22 kg/m2 and among those with BMI ≥ 37 kg/m2 compared to the BMI group 22 to < 25 kg/m2.(42) Thus, morbid obesity did not appear to be protective among “healthier” ESRD patients.

The potential confounding effects of muscle mass on the association between BMI and mortality in the ESRD population was explored by Beddhu and colleagues. A total of 70,028 patients who initiated dialysis between 1995 and 1999 were stratified by level of urine creatinine excretion (> 0.55 g/day [upper 25th percentile] vs. ≤ 0.55 g/day) as reported on the USRDS 2728 Form. Compared to the ideal BMI group (18.5 –24.9 kg/m2) with > 0.55 g/d urine creatinine excretion, adults with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and urine creatinine excretion ≤ 0.55 g/day had a 14% increased risk of death (95% CI 1.10, 1.18) while those with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and urine creatinine excretion > 0.55 g/day had a 15% increased survival (95% CI 0.83, 0.87). (45) This analysis was criticized for the potential confounding effects of residual renal function.(44) However, regardless of BMI, those with high muscle mass had better survival than those with low muscle mass. This suggests that increasing muscle mass in hemodialysis patients may improve survival.(46–48)

A major issue regarding studies examining the association between BMI and mortality in the ESRD population is the length of follow-up. Studies which demonstrate increased mortality among overweight and obese adults compared to normal BMI in the general population generally have follow-up durations that exceed 5 years.(9, 12, 49, 50) In contrast, most studies examining BMI and mortality in patients with ESRD have average follow-up durations ≤ two years.(40–43, 45) In the short-term, the presence of pre-existing disease among those with a BMI in the low end of normal will lead to greater mortality and there may be incomplete ascertainment of these co-morbid conditions. One team of investigators examined the association between BMI and mortality in two groups of adults living in The Netherlands. Hemodialysis patients (n=722) with a mean age of 66 +/− 7 years comprised the first group and the second group included 2436 adults with a mean age of 62 +/− 7 years not on dialysis who were participants of the Hoorn Study, a population based cohort. After seven years of follow-up, a baseline BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 among the hemodialysis patients was associated with a 20% (95% CI 0.8–1.7) increased risk of mortality compared to patients with an ideal BMI. Similar results were noted among the Hoorn Study group where a baseline BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 increased mortality risk by 30% (95% CI 0.9 – 2.0) compared to an ideal BMI. The confidence intervals for both populations included 1 most likely due to inadequate power, but the magnitude and direction of the association between obesity and 7-year mortality in these two groups did not differ substantially.(51)

Identification of Adults with CKD Who Will Benefit from Weight Loss: CKD Stages 1–5 Not Receiving Dialysis

The management of obesity requires identification of individuals who will benefit from weight loss. Studies demonstrate that intentional weight loss improves glucose control and decreases blood pressure in the general population,(52) two important factors for CKD progression.(53) Even moderate weight loss will reduce the metabolic demands on the kidney(54) and may delay the progression of CKD. In fact, weight loss has been shown to reduce proteinuria in both diabetic and non-diabetic kidney diseases.(55) The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) recently published Clinical Practice Guidelines (where evidence is strong) and Clinical Practice Recommendations (where evidence is limited) for Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease.(56) Weight goals are addressed in the clinical practice recommendations section due to the dearth of evidence for the diabetic CKD population. Although these recommendations suggest that patients with CKD should maintain a BMI in the range of 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, this is largely based on extrapolation from other populations. As such, the clinical practice recommendations strongly encourage development of data-driven optimal BMI targets for patients with CKD.(56)

Maintaining behavioral changes for weight loss in obese individuals is very challenging, and common CKD co-morbidities such as decreased exercise capacity only compound this difficulty. Since obtaining an ideal BMI may be especially challenging for many obese patients with CKD, clinicians should emphasize benefits of even modest weight loss and an overall healthy lifestyle which encompasses diet, exercise, smoking cessation, and moderation of alcohol intake. The American College of Physicians guidelines for obesity in primary care state that clinicians should counsel all patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 on lifestyle changes for weight loss and that weight loss goals should be individually determined.(57) In adults with CKD, abdominal obesity, as measured by waist circumference, should also be considered an indication for weight loss due to the strong association between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and CKD.(31, 32, 58) Suggested recommendations for patients with CKD who should receive interventions for weight loss are shown in Table 1.

Regardless of BMI and waist circumference, all individuals with diabetes should receive medical nutrition therapy according to the American Diabetes Association guidelines.(59) Since many adults with CKD have diabetes, these recommendations apply to a large proportion of the CKD population and include reduced intake of total energy, saturated and trans-fatty acids, cholesterol and sodium and increased physical activity. Although BMI goals were not specified in these guidelines, they emphasize the likely benefits of a 5–10% weight loss including improvements in blood pressure, cholesterol and glucose control.(59) Nutritional restrictions are discouraged for older adults who are in long-term care facilities due to the high risk of malnutrition in these individuals.(59)

Patients Treated With Dialysis

Similar to the general population, increased visceral fat is associated with higher fasting plasma insulin and triglyceride levels and a higher prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis among dialysis patients without diabetes mellitus.(60–62) A small study of 197 adults with stage 5 CKD showed that presence of inflammation (C-reactive protein level ≥ 10 mg/L), regardless of nutritional status, was associated with significantly higher truncal body fat mass compared to no presence of inflammation.(63) Since inflammation is strongly linked with mortality among patients receiving dialysis,(64, 65) adiposity itself is unlikely to confer a survival advantage.(66, 67) The strength of the reported association between morbid obesity and survival does not equal the marked increase in survival associated with transplantation. One of the largest studies of obesity and mortality in the dialysis population showed a 20% higher adjusted mortality risk for patients with a BMI between 22 to < 25 kg/m2 compared to those with a BMI > 37 kg/m2.(42) In contrast, dialysis patients who receive a kidney transplant have adjusted total annual survival rates up to 200% higher than patients who remain on the transplant waiting list.(68, 69)

Safety of intentional weight loss in stable dialysis patients has not been studied, but many medical centers preclude kidney transplantation for a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 due to higher rates of surgical wound infections and dehiscence, delayed graft function, and acute rejection compared to kidney transplant recipients who are not obese.(70–73) Average hospital stay after kidney transplantation is consequently longer for the obese patient compared to a patient with an ideal BMI(70). The current reimbursement structure, which penalizes centers for transplanting high-risk patients, along with other factors, may influence a center’s decision to preclude transplantation for morbidly obese patients.(74) Differences in long-term allograft and patient survival between obese and non-obese kidney transplant recipients may vary by center,(72, 75) but two large studies, which together included data from over 70,000 kidney transplant recipients, reported significantly higher rates of graft failure among adults with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 compared to patients with an ideal BMI.(70, 71) In the most recent study reported by Gore et al, morbidly obese adults had a 22% (95% CI 1.09–1.38) higher adjusted risk of graft failure compared to transplant recipients with an ideal BMI. The magnitude of the association between morbid obesity and risk for graft failure was similar to the risk for graft failure associated with diabetes in this study population (HR 1.28; 95% CI 1.19–1.36).(70) Graft survival time exceeded 80 months in approximately 50% of the morbidly obese transplant recipients versus 70% of transplant recipients with an ideal BMI.(70) Thus, graft survival is negatively affected by presence of morbid obesity. However, overall survival remains substantially and significantly improved with kidney transplantation in the obese dialysis patient.(76) Using data from the United States Renal Data System, Glanton et al showed that cadaver and living donor transplantation reduced mortality incidence among obese adults by 61% and 77%, respectively, compared to obese adults remaining on the transplant waiting list.(77) Until transplant centers change their policy of using BMI thresholds for access to kidney transplantation, obesity in a patient who would otherwise be eligible for a kidney transplant must be viewed as the most important modifiable factor which will influence their overall survival. In stable dialysis patients who are not eligible for transplantation for other reasons, benefits of weight loss need to be individually assessed based on the patient’s co-morbid conditions and nutritional status. Moreover, in the dialysis population, the focus should not simply be on weight loss but on body composition because interventions that increase muscle mass and improve overall fitness may improve survival.

Diet: CKD Stage 1–5 Not Receiving Dialysis

The goal of a dietary intervention is to maximize sustained weight loss at an optimal level, yet long-term behavioral changes remain the toughest obstacle for individuals trying to lose weight. Accordingly, one single dietary intervention cannot be broadly recommended. Instead, clinicians need to work with dieticians, nurses, psychologists and social workers to determine the particular needs, motivations and barriers for each patient. As food prices continue to increase, many patients may have difficulty affording healthy foods, an important consideration when determining a diet plan. Before recommending weight loss, the patient should be assessed for existing co-morbid conditions due to obesity and medications which could contribute to weight gain should be delineated. A diet history should be taken, and past experience with weight loss should be discussed.(78) There are a wide variety of healthy diets which can be considered, and these have been previously summarized in an excellent review.(79) A conservative approach is to restrict caloric intake by approximately 500 calories per day, which in the absence of physical activity changes will lead to a weight loss of one pound per week.(78) More restrictive diets (< 1200 calories/day) should be accompanied by intensive monitoring of the nutritional status and well being of the patient. Increasing physical activity in the absence of diet may lead to modest weight loss, and improvement in many obesity related co-morbid conditions(78) but may not be sufficient for the morbidly obese. Potential benefits of exercise to enhance weight loss and improve muscle mass in all adults with CKD, including persons who receive a kidney transplant, deserves further investigation.(80) Because weight gain is so common after kidney transplantation, dietary counseling for healthy diets with portion control should be provided prior to transplantation with intensive and frequent follow-up after transplantation. Studies have documented that such interventions can ameliorate weight gain after kidney transplantation.(81, 82)

The American Heart Association guidelines for a healthy lifestyle provide no specific recommendations for diet and state that the exact percentage of carbohydrates, protein and fat within a given meal will not itself influence weight management. Addressing portion size and reducing energy intake below energy expenditure remains the only reliable method to facilitate weight loss.(83) High protein diets for weight loss are extremely popular, and they appear to be useful for short-term weight loss in some individuals, but their long-term safety remains unknown.(84) In adults with CKD, protein intake exceeding 20% of total calories is not recommended due to the potential detrimental effects on kidney damage and function.(85, 86) The NKF KDOQI guideline for nutritional management of diabetes and CKD recommends that protein should meet, but not exceed the Recommended Daily Allowance of 0.8 gm/kg/day with 50–75% of the protein derived from lean poultry, fish and vegetables.(56) Diets that emphasize the consumption of whole foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains as well as the avoidance of processed foods will provide additional benefits beyond those associated with weight loss. Additional information on effects of specific nutrients on CKD initiation and progression, however, is needed to better define optimal diets.

Diet: Patients Receiving Dialysis

Guidelines for nutritional management of patients receiving dialysis currently recommend a protein intake of 1.2 gm/kg/day and 30–35 kcal/kg/day for stable patients.(87) However, obese dialysis patients must reduce caloric consumption to levels less than energy expenditure in order to lose weight. Individualized treatment plans that encompass the nutritional requirements of the ESRD population are required to optimize patient outcomes. Consistent with behavioral interventions for any patient, dietary histories and food diaries are useful to determine sources of empty calories and areas where behavioral modifications will be most helpful. Currently, evidence to support particular diets and interventions for weight loss in patients with ESRD remains scant. A wide variety of methods may be used to create a caloric-restricted dietary plan to facilitate weight loss in this unique patient population. One conservative approach is to start with a 25 kcal/kg/day based on the adjusted body weight [ideal body weight – (dry total body weight – ideal body weight/4)]. This suggested caloric intake can be used as a starting point, but should be modified based on the patient’s results with weight loss (personal communication Judith Fitzhugh Northwestern Memorial Hospital- August 17, 2008). Utilizing the adjusted body weight is not as reliable as direct measures of resting energy expenditure.(6) Hence, research is needed to determine efficacy and safety of using adjusted body weight to guide caloric intake along with other potential methods.

Pharmacologic treatment of obesity

After 6–12 months, recidivism becomes a difficult issue for even the most dedicated dieter. Most obese adults will have difficulty maintaining even a minimal to moderate weight loss and may not ever reach, let alone maintain, an ideal BMI. Weight loss medication may be used as an adjunctive therapy when diet and exercise alone have failed.(88) However, additional weight loss from pharmacologic agents is usually modest.(57) Several drugs are used for the treatment of obesity, but none has been adequately tested in adults with stage 3–5 CKD. A tabulation of medications which have been investigated for weight loss in at least one randomized trial is shown in Table 2. Some of the anorexic medications, which include phentermine, diethylpropion, sibutramine along with other medications now off the market, have been associated with development of primary pulmonary hypertension and valvular heart disease. These drugs can also can increase blood pressure and should not be used in patients with history of cardiovascular disease, cardiac arrhythmia or stroke.(89) Considering the high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in adults with CKD, these drugs should probably be avoided in adults with kidney disease as well. To achieve weight loss with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine and sertraline), high doses usually are required, which may not necessarily be safe in a patient with CKD or ESRD for long-term use. Rimonabant antagonizes the CB-1 cannabinoid receptor and reduces consumption of sweet and high fat foods and enhances weight loss with caloric restricted diets.(89) The drug was approved by the European Medical Agency in 2006 to aid weight loss with diet and exercise in obese adults, but due to increased risk of mood disorders, the drug has not been approved for use in the U.S.(90)

Table 2.

Identification of Adults Who May Benefit from Lifestyle Modifications and Weight loss

|

1Lifestyle Modification |

Weight loss | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CKD Stages 1–2 (Kidney damage with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 body surface area) | All | Presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or increased waist circumference3 | (56, 59, 83) |

| CKD Stages 3–5 Not Receiving Dialysis (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 body surface area) | All | Presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or increased waist circumference3 | (56, 59, 83) |

| Patients Receiving Dialysis | All | 2Preclusion from transplantation due to obesity |

CKD Stages defined by the National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease.(126)

Lifestyle modifications include following a healthy diet and engaging in regular exercise

Individual assessment for benefits of weight loss should be made in all patients receiving dialysis regardless of transplantation status

≥ 102 and 88 cm in men and women, respective; Asian populations ≥ 89 and 79 cm in men and women, respectively

Orlistat, a reversible inhibitor of gastric and pancreatic lipases, blocks approximately 30% of triglyceride gastrointestinal absorption and may be safe to use in many patients with CKD. The drug is characterized by very limited systemic absorption with doses up to 800 mg daily yielding minimal plasma concentrations.(91) Studies have demonstrated that the addition of orlistat to a caloric restricted diet leads to greater weight reduction compared to the addition of a placebo.(92, 93) Orlistat is available without a prescription, and the 60 mg tablet is taken three times daily within an hour of each meal. Because the drug interferes with cyclosporine absorption, (94, 95) it should not be prescribed to patients taking calcineurin inhibitors. Use of orlistat leads to incremental reductions in free fatty acids, total cholesterol, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and improves insulin resistance beyond those expected with weight reduction.(91, 96). This may be a function of the drug’s beneficial effects on free fatty acids and subsequent improvements in insulin resistance.(96)

The social consequences of orlistat could be substantial for a given patient. Fat intake must be limited to < 30% of total calories at each meal; otherwise individuals are likely to experience diarrhea and fecal incontinence if the drug is taken with a high fat meal. One study noted 16% of persons taking orlistat reported fecal incontinence,(92) but this side effect is usually temporary.(78) Fat soluble vitamin deficiencies may also occur, and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation is usually required with chronic orlistat therapy.(92) Although coumadin use is not a contraindication for orlistat use, clinicians need to consider increasing the surveillance of prothombin times, especially when orlistat is taken for a prolonged period of time. Orlistat use has also been associated with acute kidney injury due to renal oxalosis in an adult with CKD.(97) Thus, patients with CKD who use this drug should be monitored closely.

Bariatric surgery

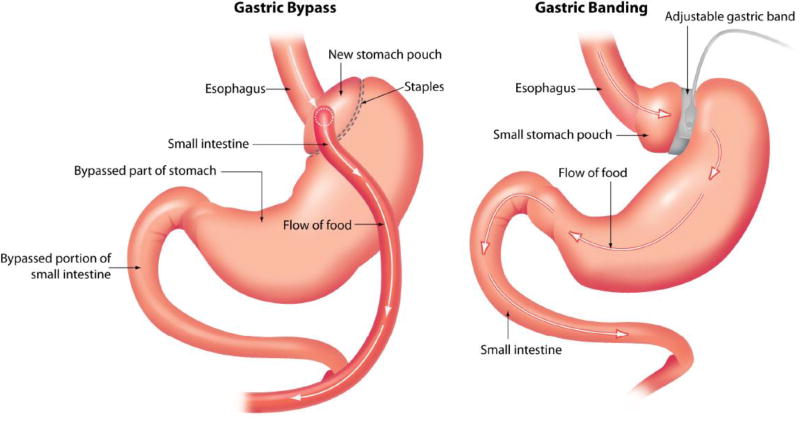

Facilitating weight loss in morbidly obese patients is frustrating because the majority fail non-surgical interventions.(98) For those patients with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 and diabetes or other obesity related co-morbid condition, bariatric surgery should be considered for treatment of obesity.(57, 59, 98, 99) Bariatric surgery procedures (Figure 2) include those which divert food from the stomach into lower parts of the digestive tract limiting absorption and those that restrict gastric capacity.(98) The Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion both reduce stomach size and divert food from the stomach into the lower part of the digestive tract.(98) During adjustable gastric banding procedures, a band is placed around the upper part of the stomach and the band may be adjusted by injecting or removing saline through a port positioned underneath the skin.(98) In 2006, Medicare agreed to provide coverage for open and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and open and laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for adults with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 and at least one obesity related co-morbidity who failed non-surgical treatments. However, coverage is limited to procedures performed at facilities certified by the American College of Surgeons as a Level 1 bariatric surgery center or certified by the American Society for Bariatric surgery as a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence (98) due to substantially higher mortality rates when these procedures are performed by inexperienced surgeons and centers.(100) A list of approved facilities is listed on the Center for Medicare Services web-site (www.cms.hhs.gov/center/coverage.asp).(98) Other procedures such as intestinal bypass and gastric balloon procedures are not covered due to safety concerns and efficacy.(98) Mortality rates after gastric bypass procedure are < 2%, with higher rates among those with BMI > 50 kg/m2.(101, 102) Laparoscopic gastric banding appears the safest with mortality rates < 0.5% in the hands of an experienced surgeon.(101, 102)

Figure 2.

Cartoon depicting bariatric surgery procedures. The right hand side shows gastric banding procedures which restricts gastric capacity. Gastric bypass procedures (left) reduce stomach size and divert food from the stomach into the lower part of the digestive tract.

Maximal weight loss is usually noted after one to two years regardless of the type of surgery.(102, 103) Biliopancreatic diversion or duodenal switch procedures yield the highest percentage of excess weight loss (70.1%) while excess weight loss associated with gastric banding procedures average 47.5%.(102) Intentional weight loss, even small to moderate amounts, is associated with multiple beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk factors such as fasting glucose and blood pressure.(104) Reflecting the substantial weight loss that may occur with bariatric surgery, chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes may resolve, as defined by presence of normal glucose levels without medications, in up to 98% of individuals undergoing gastric bypass and 48% undergoing gastric banding. (102) Both systolic and diastolic blood pressure are reduced after bariatric surgery and the majority of hypertensive adults will have either improved or resolved hypertension.(102) Other co-morbidities including dyslipidemias, sleep apnea, and fatty liver may also improve or resolve after bariatric surgery.(101) Most importantly, bariatric surgery appears to lengthen survival of morbidly obese adults.(105, 106)

Patients considering bariatric surgery for obesity management must be fully cognizant of the potential surgical complications associated with these procedures. In general, adults with CKD may be at higher risk for complications due to propensity for infections (107) and presence of co-morbid conditions. Older adults and those with established cardiovascular disease are known to be at high risk for complications(106) with up to 20% of adults > age 65 years experiencing an adverse event following bariatric surgery.(108) The most common complications are gastrointestinal tract related with over half of bariatric surgery patients hospitalized for digestive disorders within a five year post-operative period in one series.(109) Nutritional complications including iron, calcium, B and fat soluble vitamin deficiencies are common after gastric bypass procedures whereas nutritional deficiencies after banding procedures can usually be managed with a multivitamin.(101)

Intestinal bypass procedures can result in enteric hyperoxaluria leading to kidney stones and renal oxalosis with irreversible kidney damage. (110–113) Nasr et al reported 11 cases of adults who developed oxalate nephropathy after roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures and 8 of these patients eventually required dialysis.(111) The majority of these patients had mild CKD at baseline;(111) thus, clinicians must be aware that CKD may worsen after gastric bypass procedures. The clinical effects of oxalate hyperabsorption in patients receiving dialysis are uncertain, but oxalate-induced anemia in a patient with enteric hyperoxaluria due to Chrohn’s disease has been reported.(114) One study from a single institution reported that among 491 patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery, acute kidney injury, defined as a 50% increase in serum creatinine during the first three postoperative days or requirement of dialysis during the postoperative period, occurred in 8.5%. Two patients who developed acute kidney injury died while in the hospital.(115) Information on baseline kidney function in these patients was not delineated. Until a study systematically determines mortality and adverse event rates by presence of kidney disease, the overall safety of bariatric surgery in adults with CKD remains unknown. Despite its potential risk, bariatric surgery has demonstrated clinical benefit among adults with CKD. Successful kidney transplantation after facilitation of weight loss by bariatric surgery has been reported in morbidly obese dialysis dependent adults.(116) In one case, kidney failure resolved after gastric bypass surgery in a morbidly obese patient with glomerulonephritis.(117) Bariatric surgery has also been useful in adults who gain substantial weight after kidney transplantation.(116, 118, 119)

Psychosocial Aspects of Obesity

Depression and other psychiatric disorders frequently accompany obesity, especially morbid obesity. (120–122) Up to 30% of adults seeking bariatric surgery report depression symptoms.(123) Facilitation of weight loss with bariatric surgery has been shown to improve symptoms of depression and self-esteem.(121, 124, 125) Although pre-operative depression does not appear to negatively influence weight loss, all patients should be evaluated for depression and other mood disorders prior to surgery and behavioral and/or pharmacologic therapy should be offered.(123) Persons with a history of chronic depression prior to surgery will probably have persistence of a mood disorder after surgery despite weight loss and suicide risk may be heightened after surgery.(123) A multi-disciplinary approach must be used to evaluate patients desiring bariatric surgery and mood disorders must be included in the overall patient assessment.

Summary

All adults, including those with and without CKD should receive counseling on the benefits of a healthy lifestyle which includes a healthy diet, physical activity and smoking cessation. In people with CKD who are overweight, but not obese, potential benefits of weight loss to the recommended “ideal” range are uncertain. Nevertheless, obesity is associated with increased inflammation, insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidemia and overweight adults with CKD should be counseled about the risks of weight gain. Among persons with CKD and generalized or abdominal obesity, weight loss should be encouraged. For patients receiving dialysis, survival can be greatly increased with kidney transplantation. Patients who are not eligible for transplantation due to obesity should receive lifestyle and medical interventions for weight loss. If nutritional and medical management fails, bariatric surgery by an experienced surgeon at a certified center may be considered. When eligibility for transplantation is not an issue for an obese patient receiving dialysis, individualized approaches are needed and interventions should emphasize a healthy lifestyle and exercise which can increase muscle mass. Studies are urgently needed to define the benefits and risks of weight loss by lifestyle interventions, medications, and surgery for obese patients with CKD.

Table 2.

Review of Medications Evaluated for Weight Loss

| Drug | Mechanism of Action | Potential Side Effects | Drug interactions | Safe in Kidney Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Orlistat | Lipase inhibitor | Fecal incontinence, fat soluble vitamin deficiency | Cyclosporine, amiodarone | *Probably |

| 1Sibutramine | Combined norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor Anorexic | CNS stimulation, tachycardia, increased blood pressure | Serotonergic agents erythromycin, ketoconazole | No (severe renal impairment) Questionable with mild to moderate renal impairment |

| 1Diethylpropion 1Phentermine | Stimulate release of norepinephrine Anorexic | CNS stimulation, sleep disorders, tachycardia, increased blood pressure, abuse potential | MAO inhibitor therapy, concurrent use with other anorectic agents, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | Questionable Approved for short term use only due to abuse potential Avoid in patients with advanced arteriosclerosis and severe hypertension |

| Fluoxetine Sertraline | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Anxiety, tremors, sleep disorders, nausea, increased suicide risk in < 24 years of age | MAO inhibitors | Safety of prolonged administration in stage 4–5 CKD unknown. High doses required for weight loss but dose reduction suggested with severe renal impairment |

| Rimonabant | Cannabinoid receptor antagonist | Depressed mood, nausea, fatigue | Limited data | Yes, but not available in U.S. |

| Bupropion | Dopamine-Reuptake Inhibitor | Dry mouth, insomnia | MAO inhibitors | Reduce dose with stage 5 CKD |

Acknowledgments

Funding support R01 DK078112 Adipokines in hemodialysis patients (SB)

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services PHS, Office of the Surgeon General, editor. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C.; 2001. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Chen X, Song Y, Caballero B, Cheskin LJ. Association between obesity and kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2008;73:19–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin KA, Kramer H, Bidani AK. Adverse renal consequences of obesity. Am J Physiology - Renal Phys. 2008;294:F685–696. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00324.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM. Criteria for definition of overweight in transition: background and recommendations for the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1074–1081. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey KS. Methods for determining healthy body weight in end stage renal disease. J Renal Nutr. 2006;16:269–276. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutrition and your health: dietary guidelines for Americans. Washington D.C.: US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation on obesity, Geneva, June 3–5. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durazo-Arvizu RA, McGee DL, Cooper RS, Liao Y, Luke A. Mortality and optimal body mass index in a sample of the US population. Am J Epi. 1998;147:739–749. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW., Jr Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1097–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andres R, Elahi D, Tobin JD, Muller DC, Brant L. Impact of age on weight goals. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1985;103:1030–1033. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-6-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens J, Cai J, Pamuk ER, Williamson DF, Thun MJ, Wood JL. The effect of age on the association between body-mass index and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabowski DC, Ellis JE. High body mass index does not predict mortality in older people: analysis of the Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2001;49:968–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens J, Cai J, Juhaeri Thun MJ, Williamson DF, Wood JL. Consequences of the use of different measures of effect to determine the impact of age on the association between obesity and mortality. Am J Epi. 1999;150:399–407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:763–778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA. 2003;289:187–193. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:24–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heiat A, Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM. An evidence-based assessment of federal guidelines for overweight and obesity as they apply to elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1194–1203. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abell JE, Egan BM, Wilson PW, Lipsitz S, Woolson RF, Lackland DT. Differences in cardiovascular disease mortality associated with body mass between Black and White persons. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:63–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durazo-Arvizu R, Cooper RS, Luke A, Prewitt TE, Liao Y, McGee DL. Relative weight and mortality in U.S. blacks and whites: findings from representative national population samples. Ann Epi. 1997;7:383–395. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigaard J, Frederiksen K, Tjonneland A, et al. Waist circumference and body composition in relation to all-cause mortality in middle-aged men and women. Int J Obesity. 2005;29:778–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rankinen T, Kim SY, Perusse L, Despres JP, Bouchard C. The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis. J Int Assoc Study Obesity. 1999;23:801–809. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeder BA, Senthilselvan A, Despres JP, et al. The association of cardiovascular disease risk factors with abdominal obesity in Canada. Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. CMAJ. 1997;157(Suppl 1):S39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pouliot MC, Despres JP, Lemieux S, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Card. 1994;73:460–468. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2074–2079. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balkau B, Deanfield JE, Despres JP, et al. International Day for the Evaluation of Abdominal Obesity (IDEA): a study of waist circumference, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus in 168,000 primary care patients in 63 countries. Circ. 2007;116:1942–1951. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311:158–161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narisawa S, Nakamura K, Kato K, Yamada K, Sasaki J, Yamamoto M. Appropriate waist circumference cutoff values for persons with multiple cardiovascular risk factors in Japan: a large cross-sectional study. J Epi. 2008;18:37–42. doi: 10.2188/jea.18.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koster A, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A, et al. Waist circumference and mortality. Am J Epi. 2008;167:1465–1475. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C, Rexrode KM, van Dam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Circ. 2008;117:1658–1667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Muntner P, Hamm LL, et al. Insulin resistance and risk of chronic kidney disease in nondiabetic US adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:469–477. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000046029.53933.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Muntner P, Hamm LL, et al. The metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease in U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:167–174. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kramer H, Luke A, Bidani A, Cao G, Cooper R, McGee D. Obesity and prevalent and incident chronic kidney disease: The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:587–594. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Go AS. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:21–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelber RP, Kurth T, Kausz AT, et al. Association between body mass index and CKD in apparently healthy men. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:871–880. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanches F, Avesani C, Kamimura M, et al. Waist circumference and visceral fat in CKD: A cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:66–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elsayed EF, Tighiouart H, Weiner DE, et al. Waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index as risk factors for cardiovascular events in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:49–57. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwan BC, Murtaugh MA, Beddhu S. Associations of body size with metabolic syndrome and mortality in moderate chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:992–998. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04221206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madero M, Sarnak MJ, Wang X, et al. Body mass index and mortality in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:404–411. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leavey SF, McCullough K, Hecking E, Goodkin D, Port FK, Young EW. Body mass index and mortality in 'healthier' as compared with 'sicker' haemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2386–2394. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.12.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleischmann E, Teal N, Dudley J, May W, Bower JD, Salahudeen AK. Influence of excess weight on mortality and hospital stay in 1346 hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1560–1567. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johansen KL, Young B, Kaysen GA, Chertow GM. Association of body size with outcomes among patients beginning dialysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:324–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Kilpatrick RD, et al. Association of morbid obesity and weight change over time with cardiovascular survival in hemodialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:489–500. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalantar-Zadeh K. Obesity paradox in patients on maintenance dialysis. In: Wolf G, editor. Obesity and the kidney. Basel Switzerland: S. Karger AG; 2006. pp. 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beddhu S, Pappas LM, Ramkumar N, Samore M. Effects of body size and body composition on survival in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2366–2372. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000083905.72794.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beddhu S. The body mass index paradox and an obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis syndrome in chronic kidney disease. Seminar Dialysis. 2004;17:229–232. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kakiya R, Shoji T, Tsujimoto Y, et al. Body fat mass and lean mass as predictors of survival in hemodialysis patients.[see comment] Kidney Int. 2006;70:549–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Wu DY, et al. Associations of body fat and its changes over time with quality of life and prospective mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:202–210. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindsted KD, Singh PN. Body mass and 26-year risk of mortality among women who never smoked: findings from the Adventist Mortality Study. Am J Epi. 1997;146:1–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGee DL, Diverse Populations C. Body mass index and mortality: a meta-analysis based on person-level data from twenty-six observational studies. Ann Epi. 2005;15:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Mutsert R, Snijder MB, van der Sman-de Beer F, et al. Association between body mass index and mortality is similar in the hemodialysis population and the general population at high age and equal duration of follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:967–974. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circ. 2006;113:898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Goldberg R, et al. The effect of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention on the metabolic syndrome: the Diabetes Prevention Program randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:611–619. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Herman M, Hirsh J, Gafter U, Ori Y. The effects of weight loss on renal function in patients with severe obesity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1480–1486. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000068462.38661.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morales E, Valero MA, Leon M, Hernandez E, Praga M. Beneficial effects of weight loss in overweight patients with chronic proteinuric nephropathies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:319–327. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anonymous: KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations for Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Guideline 5: Nutritional management in diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:S95–S107. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snow V, Barry P, Fitterman N, Qaseem A, Weiss K. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians. Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Internal Med. 2005;142:525–531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bagby SP. Obesity-initiated metabolic syndrome and the kidney: a recipe for chronic kidney disease? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2775–2791. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000141965.28037.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bantle JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Albright AL, et al. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S61–78. doi: 10.2337/dc08-S061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kahraman S, Yilmaz R, Akinci D, et al. U-shaped association of body mass index with inflammation and atherosclerosis in hemodialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2005;15:377–386. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Odamaki M, Furuya R, Ohkawa S, et al. Altered abdominal fat distribution and its association with the serum lipid profile in non-diabetic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 1999;14:2427–2432. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.10.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamauchi T, Kuno T, Takada H, Nagura Y, Kanmatsuse K, Takahashi S. The impact of visceral fat on multiple risk factors and carotid atherosclerosis in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 2003;18:1842–1847. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Axelsson J, Rashid Qureshi A, Suliman ME, et al. Truncal fat mass as a contributor to inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1222–1229. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hung CY, Chen YA, Chou CC, Yang CS. Nutritional and inflammatory markers in the prediction of mortality in Chinese hemodialysis patients. Nephron. 2005;100:c20–26. doi: 10.1159/000084654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yeun JY, Levine RA, Mantadilok V, Kaysen GA. C-Reactive protein predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beddhu S, Ramkumar N, Samore MH. The paradox of the "body mass index paradox" in dialysis patients: associations of adiposity with inflammation. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82:909–910. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B. Resolved: being fat is good for dialysis patients: the Godzilla effect: con. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1062–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rabbat CG, Thorpe KE, Russell JD, Churchill DN. Comparison of mortality risk for dialysis patients and cadaveric first renal transplant recipients in Ontario, Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:917–922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gore JL, Pham PT, Danovitch GM, et al. Obesity and outcome following renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:357–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meier-Kriesche HU, Arndorfer JA, Kaplan B. The impact of body mass index on renal transplant outcomes: a significant independent risk factor for graft failure and patient death. Transplantation. 2002;73:70–74. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jindal RM, Zawada ET., Jr Obesity and kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:943–952. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson DW, Isbel NM, Brown AM, et al. The effect of obesity on renal transplant outcomes. Transplantation. 2002;74:675–681. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kalil RS, Hunsicker LG. The disadvantage of being fat.[comment] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:191–193. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang SH, Coates PT, McDonald SP. Effects of body mass index at transplant on outcomes of kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:981–987. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000285290.77406.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pelletier SJ, Maraschio MA, Schaubel DE, et al. Survival benefit of kidney and liver transplantation for obese patients on the waiting list. Clinical Transplants. 2003:77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glanton CW, Kao TC, Cruess D, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC. Impact of renal transplantation on survival in end-stage renal disease patients with elevated body mass index. Kidney Int. 2003;63:647–653. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eckel RH. Clinical practice. Nonsurgical management of obesity in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1941–1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0801652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Packard DP, Milton JE, Shuler LA, Short RA, Tuttle KR. Implications of chronic kidney disease for dietary treatment in cardiovascular disease. J Renal Nutr. 2006;16:259–268. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moinuddin I, Leehey DJ. A comparison of aerobic exercise and resistance training in patients with and without chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15:83–96. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel MG. The effect of dietary intervention on weight gains after renal transplantation. J Renal Nutr. 1998;8:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(98)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guida B, Trio R, Laccetti R, et al. Role of dietary intervention on metabolic abnormalities and nutritional status after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 2007;22:3304–3310. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.American Heart Association Nutrition C. Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee.[erratum appears in Circ. 2006 Dec 5;114(23):e629] Circulation. 2006;114:82–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kennedy ET, Bowman SA, Spence JT, Freedman M, King J. Popular diets: correlation to health, nutrition, and obesity. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2001;101:411–420. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friedman AN. High-protein diets: potential effects on the kidney in renal health and disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:950–962. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Uribarri J, Tuttle KR. Advanced glycation end products and nephrotoxicity of high-protein diets. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1293–1299. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01270406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Anonymous: Clinical practice guidelines for nutrition in chronic renal failure. K/DOQI, National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:S1–140. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.v35.aajkd03517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, et al. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:532–546. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bray GA, Greenway FL. Pharmacological treatment of the overweight patient. Pharmacological Rev. 2007;59:151–184. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.2.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.FDA Briefing Document. [accessed August 18, 2008];NDA 21-888 Zimulti (rimonabant) Tablets, 20 mg Sanofi Aventis Advisory Committee 2007. ttp://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/AC/07/briefing/2007-4306b1-fda-backgrounder.pdf.

- 91.Henness S, Perry CM. Orlistat: a review of its use in the management of obesity. Drugs. 2006;66:1625–1656. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666120-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finer N, James WP, Kopelman PG, Lean ME, Williams G. One-year treatment of obesity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study of orlistat, a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor. J Int Assoc Stud Obesity. 2000;24:306–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjostrom L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155–161. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nagele H, Petersen B, Bonacker U, Rodiger W. Effect of orlistat on blood cyclosporin concentration in an obese heart transplant patient. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:667–669. doi: 10.1007/s002280050690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhi J, Moore R, Kanitra L, Mulligan TE. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of the possible interaction between selected concomitant medications and orlistat at steady state in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:1011–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kelley DE, Kuller LH, McKolanis TM, Harper P, Mancino J, Kalhan S. Effects of moderate weight loss and orlistat on insulin resistance, regional adiposity, and fatty acids in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:33–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Singh A, Sarkar SR, Gaber LW, Perazella MA. Acute oxalate nephropathy associated with orlistat, a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:153–157. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Phurrough S, Salive M, Brechner R, Tillman K, Harrison S, O'Connor D. Decision Memo for Bariatric Surgery for the treatment of Morbid Obesity. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Consensus Development Conference Panel. NIH conference: gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JA, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1903–1908. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bouldin M, Ross L, Sumrall C, Loustalot F, Low A, Land K. The effect of obesity surgery on obesity comorbidity. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331:183–193. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric Surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Anderson J, Konz E. obesity and disease management: Effects of weight loss on co-morbid conditions. Obes Res. 2001;9:326S–334S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Flum DR, Dellinger EP. Impact of gastric bypass operation on survival: a population-based analysis. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2004;199:543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Liakopoulos V, Kartsios C, Stefanidis I. Disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. Sem Dialysis. 2007;20:440–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Livingston EH, Langert J. The impact of age and Medicare status on bariatric surgical outcomes. Archives of Surgery. 2006;141:1115–1120. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surgery. 2004;240:416–423. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137343.63376.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Asplin JR, Coe FL. Hyperoxaluria in kidney stone formers treated with modern bariatric surgery. J Urology. 2007;177:565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nasr SH, D'Agati V, Said SM, et al. Oxalate neprhopathy complicating roux-en-Y gastric bypass: an underrecognized cause of irreversible renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 doi: 10.2215/CJN.02940608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sinha MK, Collazo-Clavell ML, Rule A, et al. Hyperoxaluric nephrolithiasis is a complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Kidney Int. 2007;72:100–107. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nelson WK, Houghton SG, Milliner DS, Lieske JC, Sarr MG. Enteric hyperoxaluria, nephrolithiasis, and oxalate nephropathy: potentially serious and unappreciated complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Rel Dis. 2005;1:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bernhardt WM, Schefold JC, Weichert W, et al. Amelioration of anemia after kidney transplantation in severe secondary oxalosis. Clin Nephrol. 2006;65:216–221. doi: 10.5414/cnp65216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Thakar CV, Kharat V, Blanck S, Leonard AC. Acute kidney injury after gastric bypass surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:426–430. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03961106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Koshy A. Laparoscopic gastric banding surgery performed in obese dialysis patients prior to kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Soto FC, Higa-Sansone G, Copley JB, et al. Renal failure, glomerulonephritis and morbid obesity: improvement after rapid weight loss following laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:137–140. doi: 10.1381/0960892052993413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Newcombe V, Blanch A, Slater GH, Szold A, Fielding GA. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding prior to renal transplantation. Obes Surg. 2005;15:567–570. doi: 10.1381/0960892053723349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Alexander JW, Goodman H. Gastric bypass in chronic renal failure and renal transplant. Nutr Clin Prac. 2007;22:16–21. doi: 10.1177/011542650702200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosomatic Med. 2008;70:288–297. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181651651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schowalter M, Benecke A, Lager C, et al. Changes in depression following gastric banding: a 5- to 7-year prospective study. Obes Surg. 2008;18:314–320. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Eaton WW. Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epi. 2003;158:1139–1147. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, Fabricatore AN, Jones L, Stack R, Williams NS. Psychosocial and behavioral status of patients undergoing bariatric surgery: what to expect before and after surgery. Med Clin N Am. 2007;91:451–469. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O'Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Arch ntern Med. 2003;163:2058–2065. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Emery CF, Fondow MD, Schneider CM, et al. Gastric bypass surgery is associated with reduced inflammation and less depression: a preliminary investigation. Obes Surg. 2007;17:759–763. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney disease: Evaluation, Classification and Stratification. Part 4. Definition and classification of stages of chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S72–S75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]