Abstract

Background

Odontogenic infections range from peripheral abscess to superficial and deep infections leading to severe infections in head and neck region. This study was aimed to assess bacterial isolates responsible for orofacial infection of odontogenic origin and their drug susceptibility patterns so as to provide better perceptive for the management of odontogenic infections.

Methods

The study was made in a selected cohort of patients, irrespective of age and gender having moderate and severe orofacial infections of odontogenic origin admitted to Yenepoya University Hospital. Pus samples were collected and identification of bacteria was performed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method.

Result

A total of 37 study subjects were included, with bacterial isolation rate of 31 (83.7 %). The mean age presented of all patients was 40.62. Of all, 24 (64.9 %) were males. Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter claocae subsp. dissolvens, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. anaerobius and Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae were the most prevalent isolates. Result showed that 58.6 % of the isolates were resistant to gentamicin, 52.5 % for ampicillin, 51.3 % for piperacillin; least resistant being 18.9 % for azithromycin.

Conclusion

High prevalence of bacterial isolates was found, Staphylococcus aureus being the dominant. Most of the bacteria were resistant to different classes of antibiotics. Appropriate antibiotics should be given based on the bacterial isolates, culture sensitivity and clinical course of the disease.

Keywords: Odontogenic infection, Orofacial abscesses, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, Antibiotic susceptibility

Introduction

Odontogenic infection is the most frequently occurring infection in the orofacial region and has plagued human kind for many centuries. Orofacial infections due to pyogenic cause are most commonly odontogenic in origin [1] and range from periapical abscesses to superficial and deep infections in the neck [2]. These infections are usually due to dental caries, periodontitis, pericoronitis, trauma to the dentition and to some extent, due to the complications of dental procedures [3, 4]. Successful management of these infections depends upon changing the environment through decompression, removal of etiologic factor and by choosing proper antibiotic [2].

According to National Centre for Disease Control and Prevention estimate, approximately one-third of all outpatient antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary [5]. Antibiotic prescribing may be associated with the development of resistance and unfavorable side effects [6]. Despite all the improvements in diagnostic tests and the availability of modern antibiotic therapy, such infections continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality rates, especially when there is no early treatment [7, 8].

Serious complications associated with antibiotic use have encouraged studies investigating antibiotic prescribing practices of dentists [9–13]. Moreover, the choice of antibiotic for the management of odontogenic infection ideally depends on the proper culture and sensitivity profile. Patients with these infections generally prescribed with antibiotics on an empirical basis without knowing exact pathogens involved. Such antibiotic therapy may or may not yield favourable results due to various factors like microbial specificity and drug resistance. In immunocompromised patients, such treatment regimen leads to faster deterioration of health conditions. These limitations are further compounded with the lack of advanced facilities to rapidly and accurately identify the pathogenic microorganisms.

An understanding of the pathobiology and proper management of these infections is of critical importance to the dental practitioner. Difference in geography, prevalence of resistant bacterial strains and local antimicrobial prescribing practices leads to variation in the antibiotic profile of bacteria among population [14]. Up to date information on microbial resistance pattern at national and local levels should guide the rational use of the existing antimicrobial drugs [15]. Early detection of pathogens and improved methods of diagnosis are required for better health-care system. Since microorganisms vary from region to region as do their susceptibilities, it is of vital importance that such studies are to be done. This will help in monitoring the continuous evolution of susceptibility of bacteria to commonly used drugs. There have been claims in the literature that changes have occurred in the causative organisms of maxillofacial infections [16]. Therefore, a potential clinical and microbiological study was designed to check the validity of such claims. Aim of the present study was to identify the bacteria responsible for orofacial infections and to find out their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern against commonly prescribed antibiotics.

Methods

The study was carried out during May 2012 to April 2014 in a selected cohort having moderate and severe orofacial infections of odontogenic origin, admitted to Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Yenepoya University Hospital, Mangalore (India). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and a written informed consent was obtained from the all subjects. Patients undergoing antibiotics treatment and/or underwent incision and drainage were excluded. The pus samples were collected by aspirating abscess from the intraoral and/or extra orally maintained asepsis, using a disposable syringe (5 ml) filled with disposable needle of 18/22 gauges. Extra oral approach was preferred to eliminate contamination by the oral flora. Samples were collected aseptically and immediately transported to the laboratory for microbiological study.

Each specimen was grossly examined for the appearance with regard to colour and consistency. The aspirated pus was immediately inoculated into trypticase Soy broth and/or thioglycollate broth (Hi-media, India). All the samples were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 18–24 h. Following incubation, each separate morphological colony type was counted by using a digital colony counter. If no growth was observed, the culture was reported as “no growth”. All the similar individual colonies were further processed for Gram staining, pure cultures were obtained and further used for identification. All the specimens were handled according to the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory Standard Operating Procedures [17].

DNA Isolation and Identification of Bacteria Using 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Based on the colony morphology and cell characteristics individual strains were selected for taxonomic identification by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. DNA was extracted from 48 h grown bacterial cultures using genomic DNA extraction kit (Mo Bio, Inc) as previously described by Kämpfer et al. [18]. PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was carried out using 3F/9R universal primer pair [19, 20]. Ten microliters from PCR products were electrophoresed on 2 % agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 96 V and bands were visualized under UV trans-illumination. The amplified 16S rRNA genes were sequenced using BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit. The determination of the nucleotide sequence of PCR products were performed by an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 310, Applied Biosystem, USA). The resulting partial 16S rRNA gene sequence was compared with GenBank nucleotide database using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [21]. Further analyses of the sequences was performed using software MEGA (Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis) version 5.0 [22], after multiple alignment of data by Clustal X [23] to derive the exact phylogenetic position of the strains.

Antibiotic Sensitivity Tests

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method on Muller–Hinton agar in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns were determined using commercial antimicrobial disks (Hi-Media, India). We selected eight antibiotics with a wide range of mechanisms of action, including drugs that target cell wall, nucleic acid and protein (Table 1). After incubation, the antimicrobials efficacy was determined by measuring the diameter of the zones of inhibition. Bacterial strains were classified as Susceptible (S), Intermediate (I), or Resistant (R) according the diameter of the inhibition zone [24].

Table 1.

List of all antibiotics used in the study

| Abbreviation | Antibiotic | Concentration (meg) | Class | Main mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | Ampicillin | 10 | Penicillins | Cell wall |

| PIP | Piperacillin | 100 | Ureidopenicillin | Cell wall |

| GEN | Gentamicin | 10 | Amioglycosides | 30S protein synthesis |

| AZM | Azithromycin | 15 | Macrolides | Protein Synthesis Inhibitors |

| CTX | Cefotaxime | 30 | Cephalosporins-3rd generation | Cell Wall Synthesis |

| CPR | Ciprofloxacin | 5 | Fluoroquinolones | Gyrase |

| CAZ | Ceftazidime | 30 | Cephalosporins-3rd generation | Cell Wall Synthesis |

| TET | Tetracycline | 30 | Other | 30S protein synthesis |

Results

Demographic Characteristics

A total of 37 patients with pyogenic odontogenic infection were recruited into the study. There were 24 males (64.9 %) and 13 females (35.1 %). The mean age of the patients was 40.62 (range 9–72) years with the standard deviation of 17.58. The minimum age of female patients was 9 years and maximum age was 65 years (mean 48.45 and SD 18.566) and that for male was 16 and 72 years (mean 49.7 and SD 17.1) respectively. Peak age group of odontogenic infection was 25–50 years followed by above 50 years and below 25 years respectively (Table 2). Samples were distributed in submandibular space, sublingual space, parotid space, buccal space, submental space and lateral pharyngeal space.

Table 2.

Age and gender-wise distribution of patients with odontogenic infection

| Age group (years) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25–50 | >50 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 4 (30.8 %) | 5 (38.5 %) | 4 (30.87 %) | 13 (35.1 %) |

| Male | 6 (25 %) | 9 (37.5 %) | 9 (37.5 %) | 24 (64.9 %) |

| Total | 10 (27 %) | 14 (37.8 %) | 13 (35.1 %) | 37 (100 %) |

Bacterial Isolates and Microbiologic Evaluation

Out of the 37 samples assayed via standard culture, only 31 (83.7 %) showed bacterial growth and we found 41 bacterial isolates from these. Of the total 41 isolates, 21 (51.2 %) were Gram positive cocci and 20 (48.8 %) were Gram negative bacilli. The sequences from these samples were classified into 2 phyla, 3 classes, 4 orders, 5 families and 10 genera. The most abundant phyla detected were Firmicutes (51.2 %), followed by Proteobacteria (48.8 %). Bacteria were classified into three classes, in which Gamma proteobacteria were predominant (48.8 %) followed by Bacilli (36.6 %) and Cocci (14.6 %) respectively. The bacteria were further classified into four orders; in which Enterobacteriales (41.5 %) were predominant followed by Bacillales (31.7 %), Lactobacillales (19.5 %) and Pseudomonadales (7.3 %) respectively.

Family level distribution showed the predominance of Enterobacteriaceae (41.5 %) followed by Staphylococcaceae (31.7 %), Streptococcaceae (14.6 %), Pseudomonadaceae (7.3 %) and Enterococcaceae (4.9 %) respectively. Out of the total 10 genus detected, Staphylococcus (31.7 %), Klebsiella (19.6 %), Streptococcus (14.6 %), Enterobacter (12.3 %) were predominant followed by Pseudomonas (7.3 %) Enterococcus (4.9 %), Citrobacter, Escherichia, Proteus and Shigella (2.4 %) respectively. Staphylococcus aureus (14.6 %), Enterobacter claocae subsp. dissolvens (12.1 %), Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. anaerobius and Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae (9.6 %) were the most prevalent isolates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of bacterial isolates by 16S rRNA gene sequencing

| Bacterial isolates | Male | Female | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 (9.75 %) | 2 (4.87 %) | 6 (14.7 %) |

| Enterobacter claocae subsp. dissolvens | 3 (7.31 %) | 2 (4.87 %) | 5 (12.2 %) |

| Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipnearnoniae | 3 (7.31 %) | 1 (2.43 %) | 4 (9.8 %) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | 2 (4.87 %) | 2 (4.87 %) | 4 (9.8 %) |

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. anaerobius | 3 (7.31 %) | 1 (2.43 %) | 4 (9.8 %) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2 (4.87 %) | 1 (2.43 %) | 3 (7.3 %) |

| Staphylococcus sciuri | 3 (7.31 %) | – | 3 (7.3 %) |

| Streptococcus pyogens | 1 (2.43 %) | 2 (4.87 %) | 3 (7.3 %) |

| Enterococcus fecalis | 1 (2.43 %) | 1 (2.43 %) | 2 (4.9 %) |

| Streptococcus pneumoneae | 1 (2.43 %) | 1 (2.43 %) | 2 (4.9 %) |

| Streptococcus oralis | 1 (2.43 %) | – | 1 (2.4 %) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 (2.43 %) | – | 1 (2.4 %) |

| Escherichia coli | – | 1 (2.43 %) | 1 (2.4 %) |

| Shigella jlexneri | 1 (2.43 %) | – | 1 (2.4 %) |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1 (2.43 %) | – | 1 (2.4 %) |

| Total | 27 (65.86 %) | 14 (34.14 %) | 41 (100 %) |

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

Most of the isolates were sensitive to the antibiotics tested. The result showed that 58.6 % of the isolates were resistant to gentamicin, followed 52.5 % for ampicillin, 51.3 % for piperacillin; least resistant being 18.9 % for azithromycin. Among the isolates tested, 29.3 % of the isolates acquired resistance to ceftazidime, 26.9 % for ciprofloxacin, 24.3 % for cefotaxime and 21.2 % for tetracycline.

In our study, the resistance to piperacillin by the Gram-positive aerobes was noted in (38.1 %) of the isolates, of which S. aureus was resistant in 4 instances (50 %) to piperacillin whereas 100 % susceptibility was noted to gentamicin. Few isolates of Staphylococcus are susceptible to ampicillin. Among all Staphylococcus isolates, 92.3 % were sensitive to ceftotaxime, and 76.95 % were sensitive to ciproflaxin and azithromicin. Of all Streptococcus isolates tested, 100 % susceptibility was noted to ampicillin followed by 83.3 % to gentamicin, ciproflaxin and ceftazidime. This finding indicates that the above three antibiotics were effective in managing odontogenic infections caused by gram-positive organisms.

On the other hand, the antibiotic susceptibility of the Gram negative organisms was seen predominantly with tetracycline (70.6 %) followed by ciprofloxacin (70 %) and azithromycin (64.8 %) respectively (Table 4). E. coli was found 100 % susceptible to ampicillin whereas Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, Proteus mirabilis and Shigella flexneri was 100 % resistant to ampicillin. E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Citrobacter koseri were found 100 % susceptible to ciproflaxin while resistance to Proteus mirabilis. Ceftotaxime was found to be sensitive to Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae whereas resistance to Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae. Azithromicin was 100 % sensitive to Enterobacter claocae subsp. dissolvens but resistant to P. mirabilis.

Table 4.

Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Gram positive and Gram negative isolates

| Antibiotic | Gram positive isolates | Gram negative isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | S | I | R | |

| Ampicillin | 12 (57.1 %) | 3 (14.3 %) | 6 (28.6 %) | 4 (21.1 %) | – | 15 (78.9 %) |

| Piperacillin | 9 (42.8 %) | 4 (19.1 %) | 8 (38.1 %) | 6 (30 %) | 1 (5 %) | 13 (65 %) |

| Gentamicin | 17 (81 %) | 1 (4.8 %) | 3 (14.2 %) | 12 (60 %) | 1 (5 %) | 7 (35 %) |

| Azithromycin | 15 (75 %) | 1 (5 %) | 4 (20 %) | 11 (64.8 %) | 3 (17.6) | 3 (17.6 %) |

| Tetracycline | 10 (62.5 %) | 4 (25 %) | 2 (12.5 %) | 12 (70.6 %) | – | 5 (29.4 %) |

| Cefotaxime | 16 (83 %) | 1 (5.5 %) | 1 (5.5 %) | 11 (58 %) | – | 8 (42 %) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 14 (66.6 %) | 1 (4.8 %) | 6 (28.6 %) | 14 (70 %) | 1 (5 %) | 5 (25 %) |

| Ceftazidime | 4 (19 %) | 17 (81 %) | – | 6 (30 %) | 2 (10 %) | 12 (60 %) |

S sensitive, I intermediate, R resistant

Discussion

Anatomical and microbial factors and destruction in host resistance, compounded by a delay in receiving adequate treatment in the early stages, can result in the progression of a localized odontogenic infection [3]. Deep space infections can carry a high incidence of morbidity and mortality [25]. Presentation of patient condition is dictated by complex microflora, involved tooth and anatomic routes of spread [26]. Understanding these microorganisms involved in the infections, and sensitivity profile will help in better treatment regime, while incision and drainage is the primary treatment for sure [27]. To the above reasons, an understanding of the nature of oral flora and its dynamics is important in orofacial infections (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Fig. 1.

a Buccal space infection. b Parotid space infection. c Sub mandibular space infection. d Canine space infection involving buccal space

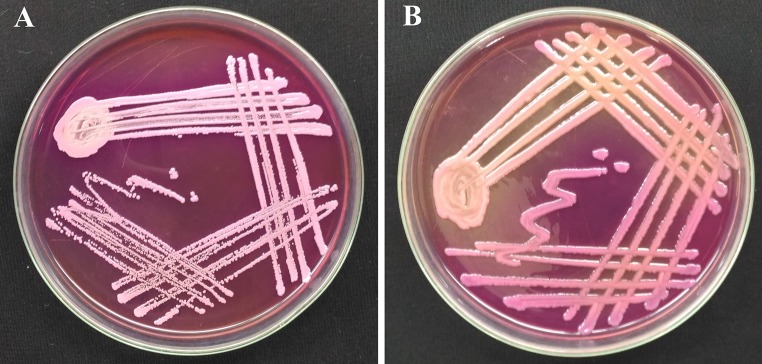

Fig. 2.

Cultures of the most commonly found bacteria in oral abscess on MacConkey agar. a Staphylococcus aureus. b Klebsiella pneumonia

Fig. 3.

Drug sensitivity pattern of the bacteria isolated from oral abscess. a Showing resistance to ampicillin. b Showing resistance to piperacillin and ampicillin

Most of the patients in our study were adults in the age group of 25–50 years as was reported in other previous studies [28, 29]. The probable reason for adults being at higher risk is the higher prevalence of systemic diseases that compromise immunity and the neglect of oral hygiene [30]. The male to female ratio presented in our study is 1.8:1, which corresponds with most of the previous studies reported [30–32]. Its probability may be due to the reason that women tends to better oral health and seek oral health care more frequently [33]. In the present study, the infections were predominated in submandibular space and was in agreement with previous reports [1, 34, 35]. The maintenance of a safe and secure airway is mandatory in submandibular space infections [36].

The traditional identification of bacteria on the basis of phenotypic characteristics is generally not as accurate as identification based on genotypic methods. Full and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing methods have emerged as useful tools for identifying phenotypically aberrant microorganisms. It is a more objective identification tool, unaffected by phenotypic variation or technical bias, and has the potential to reduce laboratory errors [37]. Moreover, some clinical microorganisms, which can hardly be identified by phenotypic methods, have been distinguished by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Study showed that, conventional identification misidentified all the tested isolates by 16S rRNA gene sequencing techniques [37]. Misidentification of bacteria may mislead clinicians, and potentially impacted patient care. 16S rRNA gene sequence presently remains the gene sequence of choice. In our study, this technique is explored for its accuracy and to overcome bias in conventional biochemical identification. The sequences were compared with NCBI databases and sequences showing 100 % similarity to any previously described species in NCBI databases were considered as belonging to same species. A 95 % gene sequence similarity ‘lower cut-off window’ for genera seems reasonable, but in practice it may not be easy to implement [38].

In our study, bacterial growth was observed in 83.7 % of the samples that were cultured aerobically, and we did not performed, anaerobic culture methods. Previous reports showed that anaerobic bacteria were detected only in small proportions [30]. On the other hand, anaerobic bacteria were found in 42.59 % of all cases [27] possibly because of presentation of patient at a later stage as aerobes predominate and when within a closed space available oxygen is utilized, anaerobes take over [26].

Of the total isolates in this study, 51.2 % were Gram positive cocci, 19 (46.3 %) were Gram negative bacilli and 1 (2.4 %) was Gram negative bacilli. These results were almost similar with recent report [27]. In the present study, gentamicin is the most resistant antibiotic presented followed by ampicillin. This finding was in accordance with previous study in which, gentamicin followed by amikacin had highest percentage of resistance [39]. Aminoglycosides are effective in controlling aerobic gram negative infections which are quite rarely encountered by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. These observations are in conformity with our study. Aminoglycoside (Gentamicin) were sensitive to Gram positive isolates (81 %) as well as Gram negative isolates (60 %). Studies showed that many species of organisms were resistant to Penicillin [32, 40].

Cephalosporins have travelled a long distance, starting from first generation reaching fifth generation at present. The reason for this evolution is obviously the resistance of infections [27]. This study indicated a difference in the sensitivity among third generation cephalosporins too. Cefotaxime was effective against 83 % of Gram positive and 58 % of Gram negative isolates, while Ceftazidime had a very low percentage against Gram positive (19 %) and Gram negative isolates (30 %). Ciprofloxacin, one of the first drugs from the Quinolone group, has been replaced by its advanced versions like Gatifloxacin and Moxifloxacin. Even though, the recent studies showed their relevance in current scenario [27, 41]. Our study found that ciprofloxacin as potent as third generation antibiotic. Cephalosporins having 70 % effective against Gram negative isolates and 66.6 % against Gram positive isolates. All these data support the importance of ciprofloxacin in antimicrobial therapy. The limitations in the study were low sample size and we could not culture the pus sample anaerobic condition due to in availability of such facility.

Antibiotic dosages should be adjusted according to patient’s age and body weight. Some of our isolates showed variation in the identification by routine biochemical identification compared to 16S rRNA gene sequencing, this highlights the limitation of routine biochemical identification. Identification of bacteria should be performed by an experienced microbiologist in order to classify the pathogenic organisms accurately. The use of antibiotics prior to admission, high dosage intravenous antibiotics prior to surgical drainage, improper collection of specimens, and the absence of routine anaerobic cultures, as well as difficulty in culturing anaerobes, could have affected the microbiological test results [30]. To overcome the resistance, there are some precautions should be taken. Firstly, massive global public awareness campaign, improve hygiene and prevent the spread of infection, improve global surveillance of drug resistance, promote new, rapid diagnostics to cut unnecessary use of antibiotics, promote development and use of vaccines and alternatives and improve the numbers, and lastly recognition of people working in infectious disease [42].

Conclusion

Staphylococcus species is the most common causative pathogen in orofacial infections of odontogenic origin. Most of the bacteria were resistant to different classes of antibiotics. Appropriate antibiotics should begin with correlation to clinical presentation without forgetting the importance of early surgical intervention to reduce morbidity and complications. Moreover antibiotics should be given based on the bacterial isolates, culture sensitivity and clinical course of the disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Yenepoya University Seed Grant (YU/Seed Grant/2011-004).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Jagadish Chandra H. and Sripathi Rao B. H. have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Huang TT, Liu TC, Chen PR, Tseng FY, Yeh TH, Chen YS. Deep neck infection: analysis of 185 cases. Head Neck. 2004;26(10):854–860. doi: 10.1002/hed.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahl R, Sandhu S, Singh K, Sahai N, Gupta M. Odontogenic infections: microbiology and management. Contemp Clin Dent. 2014;5(3):307. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.137921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uluibau IC, Jaunay T, Goss AN. Severe odontogenic infections. Aust Dent J. 2005;50(s2):S74–S81. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kityamuwesi R, Muwaz L, Kasangaki A, Kajumbula H, Rwenyonyi CM. Characteristics of pyogenic odontogenic infection in patients attending Mulago Hospital, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0382-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swift JQ, Gulden WS. Antibiotic therapy- managing odontogenic infections. Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46(4):623–633. doi: 10.1016/S0011-8532(02)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dar-Odeh NS, Abu-Hammad OA, Al-Omiri MK, Khraisat AS, Shehabi AA. Antibiotic prescribing practices by dentists: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:301. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S9736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaguchi M, Sato S, Ishiyama T, Katsuno S, Taguchi K. Characterization and management of deep neck infections. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;26(2):131–134. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brito TP, Hazboun IM, Fernandes FL, Bento LR, Zappelini CE, Chone CT, Crespo AN (2016) Deep neck abscesses: study of 101 cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Palmer NO, Martin MV, Pealing R, Ireland RS. Paediatric antibiotic prescribing by general dental practitioners in England. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(4):242–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2001.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer NO, Martin MV, Pealing R, Ireland RS. An analysis of antibiotic prescriptions from general dental practitioners in England. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46(6):1033–1035. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addy M, Martin MV. Systemic antimicrobials in the treatment of chronic periodontal diseases: a dilemma. Oral Dis. 2003;9(s1):38–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.9.s1.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demirbas F, Gjermo PE, Preus HR. Antibiotic prescribing practices among Norwegian dentists. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64(6):355–359. doi: 10.1080/00016350600844394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Haroni M, Skaug N. Incidence of antibiotic prescribing in dental practice in Norway and its contribution to national consumption. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(6):1161–1166. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noh KT, Kim CS. The changing pattern of otitis media in Korea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1985;9(1):77–87. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(85)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muluye D, Wondimeneh Y, Ferede G, Moges F, Nega T. Bacterial isolates and drug susceptibility patterns of ear discharge from patients with ear infection at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fating NS, Saikrishna D, Kumar GV, Shetty SK, Rao MR. Detection of bacterial flora in orofacial space infections and their antibiotic sensitivity profile. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13(4):525–532. doi: 10.1007/s12663-013-0575-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheesbrough M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kämpfer P, Dreyer U, Neef A, Dott W, Busse HJ. Chryseobacterium defluvii sp. nov., isolated from wastewater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53(1):93–97. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brosius J, Palmer ML, Kennedy PJ, Noller HF. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1978;75(10):4801–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards U, Rogall T, Blöcker H, Emde M, Böttger EC. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17(19):7843–7853. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.19.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wayne PA (2009) Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) performance standards for antimicrobial disk diffusion susceptibility tests 19th ed. approved standard. CLSI document M100-S19: 29

- 25.Sato FR, Hajala FA, Freire Filho FW, Moreira RW, De Moraes M. Eight-year retrospective study of odontogenic origin infections in a post graduation program on oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(5):1092–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR. Oral and maxillofacial infections. 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 99–213. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh M, Kambalimath DH, Gupta KC. Management of odontogenic space infection with microbiology study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13(2):133–139. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juncar M, Popa AR, Onisor F, Iova GM, Popa LM. Descriptive Study on Influence of Systemic Conditions on Head and Neck Infections. Applied Medical Informatics. 2011;28(1):62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juncar M, Popa AR, Baciuţ MF, Juncar RI, Onisor-Gligor F, Bran S, Băciuţ G. Evolution assessment of head and neck infections in diabetic patients–A case control study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42(5):498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew GC, Ranganathan LK, Gandhi S, Jacob ME, Singh I, Solanki M, Bither S. Odontogenic maxillofacial space infections at a tertiary care center in North India: a five-year retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16(4):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Ahani A, Pogrel MA. A five-year retrospective study of odontogenic maxillofacial infections in a large urban public hospital. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34(6):646–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Levi MH, Adamo AK, Kraut RA, Trieger N. Severe odontogenic infections, part 1: prospective report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(7):1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zakrzewska JM. Women as dental patients: are there any gender differences? Int Dent J. 1996;46(6):548–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parhiscar A, Har-El G. Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2001;110(11):1051–1054. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larawin V, Naipao J, Dubey SP. Head and neck space infections. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(6):889–893. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Da Mosto MC. Submandibular space infection: a potentially lethal infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(3):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petti CA, Polage CR, Schreckenberger P. The role of 16S rRNA gene sequencing in identification of microorganisms misidentified by conventional methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(12):6123–6125. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6123-6125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tindall BJ, Rosselló-Mora R, Busse HJ, Ludwig W, Kämpfer P. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60(1):249–266. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aderhold L, Knothe H, Frenkel G. Bacteriology of dentigenous pyogenic infections. Oral Surg. 1981;52:583–587. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rega AJ, Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(9):1377–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anthony RJ. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1377–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’neill J (2016) Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Welcome Trust & HM Government, London