Abstract

Renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) with Xp11 translocation (Xp11 RCC) constitute a distinctive molecular subtype characterized by chromosomal translocations involving the Xp11.2 locus, resulting in gene fusions between the TFE3 transcription factor with a second gene (usually ASPSCR1, PRCC, NONO, or SFPQ). RCCs with Xp11 translocations comprise up to 1–4% of adult cases, frequently displaying papillary architecture with epithelioid clear cells.

In order to better understand the biology of this molecularly distinct tumor subtype, we analyze the miRNA expression profiles of Xp11 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) compared to normal renal parenchyma using microarray and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). We further compare Xp11 RCC with other RCC histologic subtypes using publically available datasets, identifying common and distinctive microRNA (miRNA) signatures along with the associated signaling pathways and biological processes.

Overall, Xp11 RCC more closely resemble clear cell rather than papillary RCC. Further, among the most differentially expressed miRNAs specific for Xp11 RCC, we identify miR-148a-3p, miR-221-3p, miR-185-5p, miR-196b-5p, and miR-642a-5p to be up-regulated, while miR-133b and miR-658 were down-regulated. Finally, Xp11 RCC is most strongly associated with microRNA expression profiles modulating DNA damage responses, cell cycle progression and apoptosis, and the Hedgehog signaling pathway. In summary, we describe here for the first time the miRNA expression profiles of a molecularly distinct type of renal cancer associated with Xp11.2 translocations involving the TFE3 gene. Our results might help understanding the molecular underpinning of Xp11 RCC, assisting in developing targeted treatments for this disease.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, Xp11 translocation, TFE3 gene fusion, microRNA expression profiling

Introduction

Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) are a distinctive subtype of RCC characterized by chromosomal translocations with breakpoints involving the TFE3 transcription factor gene, which maps to the Xp11.2 locus [1]. The result is a fusion of the TFE3 transcription factor gene with one of multiple reported genes including ASPSCR1 (ASPL), PRCC, NONO (p54nrb), SFPQ (PSF), and CLTC [2]. The most distinctive histologic pattern is that of a neoplasm featuring papillary architecture and epithelioid clear cells [3,4]. Xp11 translocation RCCs were first recognized in children, and likely comprise the majority of pediatric RCC. The frequency of Xp11 translocation RCC in adults may be underestimated, due to morphological overlap with more common adult RCC subtypes, such as conventional clear cell RCC and papillary RCC, though most series find that Xp11 translocation RCC comprise 1–4% of adult RCC [2]. Nonetheless, adult Xp11 translocation RCCs outnumber pediatric Xp11 translocation RCCs by orders of magnitude due to the much higher incidence of RCC in the adult population. Overall, survival is similar to that of patients with clear cell RCC, and significantly worse than those of patients with papillary RCC [5].

Ellis et al. recently reviewed the published literature on Xp11 translocation RCC with the ASPSCR1-TFE3 and PRCC-TFE3 gene fusions. In multivariate analysis, only advanced stage (specifically distant metastasis) and older age at diagnosis independently predicted death [6]. At the current time, there is no standard treatment protocol for patients with Xp11 translocation RCC. By immunohistochemistry, Xp11 translocation RCCs express phosphorylated S6, a marker of elevated mTOR-pathway activation; however, only a subset of patients has responded to mTOR inhibitors [7]. Expression profiling studies had demonstrated that the MET receptor tyrosine kinase is induced by TFE3 gene fusions, and MET protein expression has been verified by immunohistochemistry; however, results of a clinical trial targeting MET in Xp11 translocation neoplasms have been disappointing [8]. Whole genome and RNA sequencing studies have demonstrated frequent mutations in chromatin remolding genes such as INOEBD in Xp11 translocation RCC, though this mutation cannot be targeted at the current time [9]. Clearly, further studies to identify novel targets in Xp11 translocation RCC are sorely needed. Of note, microRNA (miRNA) expression profiling has not previously been systematically performed on Xp11 translocation RCC.

In this study, hence, we analyze the miRNA expression profile of a set of genetically confirmed Xp11 translocation RCC, and evaluate similarities and differences between this neoplasm and clear cell and papillary RCC, in order to better understand the biologic characteristics of this molecular entity.

1. Materials and Methods

All analyses were performed using previously described methods as briefly summarized below [10].

1.1. Case selection

A total of 12 cases diagnosed as Xp11 RCC over the years 2003–2015 were retrieved from the archives of The Johns Hopkins University Hospital along with demographic and clinical information. The study received institutional review board and all investigations involving human samples were performed in strict adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki. All available haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides were reviewed and diagnosis was confirmed based on the presence of specific morphologic and immunohistochemical features as previously reported. In all cases, the diagnosis of Xp11 translocation RCC was supported by TFE3 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization FISH) or classic cytogenetics. Tumors were assessed for size, pathological stage, and International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) nucleolar grade. MicroRNA expression profiles were obtained from 8 matched tumor-normal pairs from 7 distinct patients (discovery set), while 5 additional patients were used for independent validation of selected miRNA moieties (validation set, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinico-pathological characteristics of Xp11 patients used in the study (N = 12, RN=radical nephrectomy; PN=partial nephrectomy).

| Case | Age/Sex | Procedure | Stage | Size | Nucleolar Grade | Analysis | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10/F | RN | pT2NX, II | 10.0 cm | ISUP II | Discovery set | Necrotic |

| 2 | 36/F | RN | pT2NX, II | 7.8 cm | ISUP IV | Discovery set | Sarcomatoid; recurred; SFPQ-TFE3 |

| 3 | 28/F | PN | pT1aNX, I | 3.4 cm | ISUP III | Discovery set | |

| 4 | 34/F | RN | pT2bNO, II | 12.5 cm | ISUP II | Discovery set | |

| 5 | 45/F | RN | pT3bNO (sinus), III | 8.0 cm | ISUP III | Discovery set | |

| 6 | 36/F | RN | pT3NXM1 (bone), IV | 4.7 cm | ISUP II | Discovery set | Bone metastasis at diagnosis |

| 7,8 | 14/M | RN | pT3aN0M0, III | 3.7 cm | ISUP III | Discovery set | ASPSCR1-TFE3; recurred locally x2 |

| V1 | 62/M | PN | pTXNX, unknown | 3.6 cm | ISUP II | Validation set | Margin positive |

| V2 | 56/F | PN | pT1NX, I | 4.5 cm | ISUP III | Validation set | |

| V3 | 63/F | PN | pT1NX, I | 3.5 cm | ISUP II | Validation set | SFPQ-TFE3 |

| V4 | 3/M | RN | pT1N1, III | 4.0 cm | ISUP II | Validation set | SFPQ-TFE3 |

| V5 | 31/F | RN | pT1N0, I | 5.0 cm | ISUP II | Validation set | SFPQ-TFE3 |

1.2. RNA extraction

For each case, a representative formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue sample was selected for RNA preparation. To enrich for neoplastic cells within the tissues, the representative FFPE blocks were cored with a sterile 16-gauge needle, and tumor areas showing at least 50% neoplastic cellularity were selected microscopically as previously described [7]. Total RNA was extracted using the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA) per manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was evaluated using Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

1.3. Microarray hybridization

Eight matched tumor and normal sample pairs were analyzed using the Human miRNA Microarray Kit Release 19.0, 8x60K (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocols. This microarray platform accounts for 2006 human microRNAs from the Sanger miRbase database release 19.0 (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences/). All analyzed samples showed 28S to 18S ratio > 1.2, an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8, and detectable microRNAs. Microarray analyses were performed at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center Microarray Core Facility at Johns Hopkins University using manufacture’s instruction as previously described [10]. Data were acquired with Agilent Feature Extraction 10.7.3.1 software for miRNA microarray, generating both probe-level signal intensities from all probes and summarized expression levels for each miRNA.

1.4. Technical and independent set validation of microarray data

Validation of microarray data was obtained for 4 distinct miRNA molecules selected among the most differentially expressed in the microarray experiments using TaqMan microRNA assays (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX). This validation was performed on all 8 tumor-normal pairs analyzed by microarray as well as on 5 additional cases. We used miR-432, which proved to be robust and rank-invariant in our microarray analysis, as the reference gene for normalization purposes. Ten nanograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed using TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) on a 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System per the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples were run in triplicate. Normalized signal levels for each miRNA were calculated using comparative cycle threshold method (ΔΔCT method) [11].

1.5. Statistical and Computational Analysis

1.5.1. Analysis of differential gene expression

MicroRNA expression data were processed for statistical analysis using packages from R/Bioconductor (www.bioconductor.org) as previously described [10,12–14]. Briefly, raw data were preprocessed using “state-of-the-art” protocols as implemented in the AgiMicroRna R package: first control, undetected probes, and outliers were filtered, then gene level expression summaries were obtained after normalization at the probe level using the RMA algorithm and quantile-normalization across samples. All unprocessed and normalized data along with detailed information on statistical methods used – in accordance to Minimal Information about Microarray Experiments (MIAME) standards – are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE95384). We used a generalized linear model approach, coupled with empirical Bayes to moderate standard errors of expression [15], for identifying differentially expressed miRNA between tumor and normal samples. We included coefficients for patient matching status and for data heterogeneity as derived from surrogate variable analysis (SVA) [16] whenever indicated. Multiple testing corrections were performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. We further compared microRNA expression profiles associated with the Xp11 translocation with those identified in renal cell carcinoma of other histologic type, using three previously published studies comparing different tumor groups to their normal counterparts (GSE95385 – hereafter referred to as Munari dataset [10], GSE41282 [17], and GSE37989 [18]). This analysis was performed at the global level using Correspondence At the Top (CAT) curves with confidence intervals, and by comparing the most differentially expressed miRNAs between groups with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 5% or less, as previously described [19].

1.5.2. Analysis of Functional Annotation

The identification of pathways and biological processes differentially expressed between tumor and normal was performed using the Analysis of Functional Annotation (AFA), an approach analogous to Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [20] we have successfully applied in previous studies [12,19,21]. Functional Gene Sets (FGS) corresponding to pathways and biological concepts were associated to specific microRNA based on their validated target genes as derived from the miRwalk 2.0 database [22]. Only FGS associated with more than 5 distinct microRNA were retained in the analysis. After reordering the microRNAs according to the moderated t-statistics obtained from our generalized linear model analysis, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test whether each FGS was significantly up-regulated, down-regulated, or differentially expressed in each RCC histologic subtypes under investigation compared to normal renal parenchyma. Only microRNAs annotated to each FGS collection were used as the reference population in each test. Also in this case correction for multiple hypothesis testing was obtained separately for each FGS collection, by applying the Benjamini and Hochberg multiple testing correction. AFA was applied to identify and compare enriched biological themes using the following FGS databases: 1) Disease Ontology (DO, http://disease-ontology.org); 2) Gene Ontology Biological Process (GOBP, http://amigo.geneontology.org); 3) Monarch Initiative Human Phenotypes (HP, https://monarchinitiative.org/phenotype/); 4) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html); 5) Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER, http://www.pantherdb.org/); and 6) WikiPathways (http://vm1.wikipathways.org). Overall, we analyzed at total of 9744 FGS (1427 for DO, 3317 for GOBP, 4539 for HPO, 196 for KEGG pathways, 124 for PANTHER pathways, and 141 WikiPathways).

1.5.3. Social network analysis

We reconstructed the microRNA-FGS network using weighted undirected graph, starting from the adjacency matrix representing the membership of all up-regulated microRNAs to the most enriched FGS from KEGG, PANTHER, and WikiPathways databases. We subsequently performed social network analysis to identify distinct FGS communities, using the community search algorithm based on random walks implemented by Pons et al [23]. Hierarchical clustering was used to group and display the enriched FGS based on common microRNA membership, using the binary distance and the Ward clustering method.

2. Results

2.1. Clinicopathologic characteristics and immunohistochemical profiles

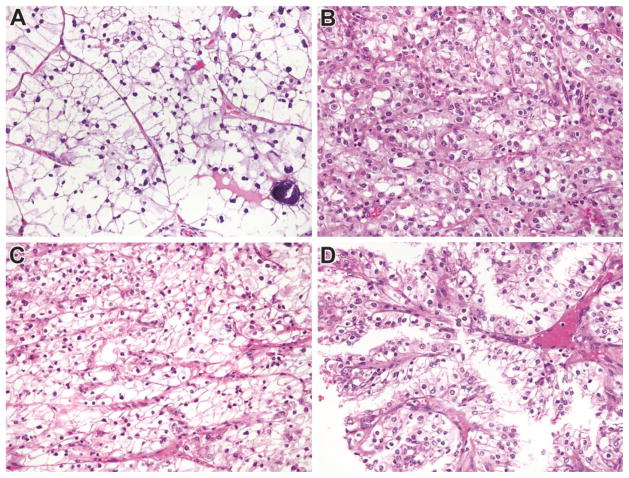

Clinicopathologic characteristics of analyzed tumors are summarized in Table 1. There were 12 cases overall; seven cases were analyzed in the discovery cohort while five were analyzed in the validation cohort. All cases were confirmed genetically either by TFE3 break-apart FISH or by cytogenetics. Mean tumor diameter was 5.9 cm. Overall, there were 9 females and 3 males, and the mean age was 34.5 years (mean 35 years). Four cases were stage I, 3 were stage II, 3 were stage III and 1 was stage IV; stage was unknown in one case. Seven cases were ISUP nucleolar grade II, four cases were ISUP nucleolar grade III, and one case was ISUP nucleolar grade IV. The TFE3 fusion partner was known in 5 cases; 4 were SFPQ-TFE3 while 1 was ASPSCR1-TFE3. Examples of typical morphological characteristics of the analyzed tumors are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Morphology of Genetically Confirmed Xp11 translocation RCC in this study. Panel A: This tumor has clear cell features and psammoma bodies; Panel B: This tumor closely resembled clear cell RCC; Panel C: This primary tumor resembled clear cell RCC; and Panel D: Recurrence of the primary tumor shown in C demonstrates papillary architecture. All images are taken at 400X magnification, and all are Hematoxylin and Eosin stained.

2.2. Genome wide miRNA expression profiling of Xp11 renal cell carcinoma

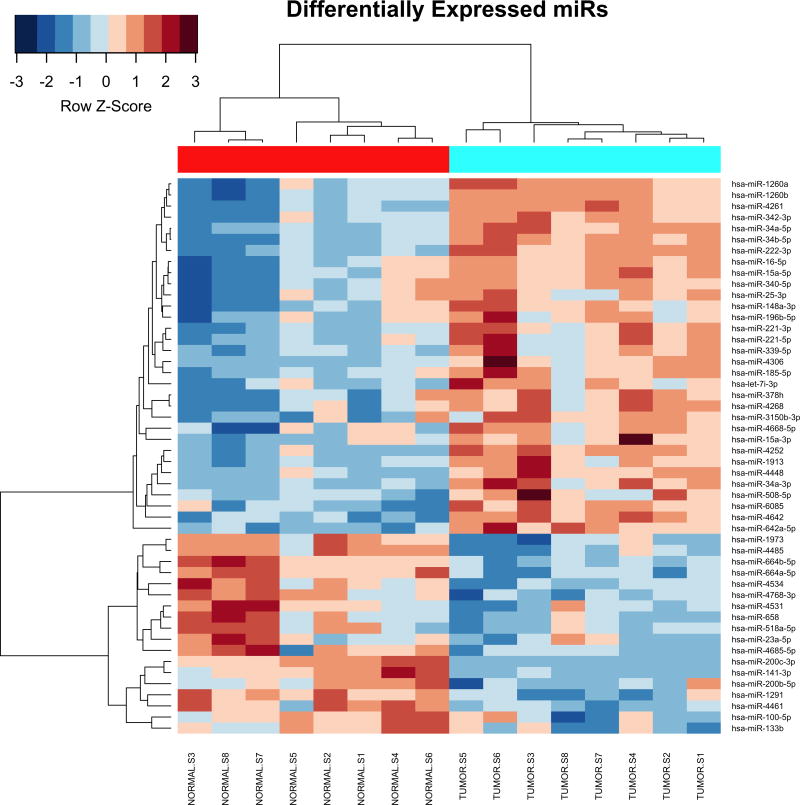

All microarray hybridizations were successful with comparable coefficients of variation between replicated probes across samples (Supplementary Figure S1A). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) revealed that Xp11 RCC tumor samples have distinct microRNA expression profiles from normal renal tissue (Supplementary Figure S1B). Among the analyzed 2,006 miRNAs, 50 mature miRNA were differentially expressed between matched Xp11 RCC tumors and normal samples with a FDR of < 5%, of which 18 were down-regulated and 32 up-regulated in tumors compared to normal samples (Supplementary Table S1). Figure 2 shows the most significantly differentially expressed (FDR < 5%) miRNAs in Xp11 RCC compared to matched normal renal parenchyma.

Figure 2.

MicroRNA expression profile Xp11 RCC. Heat-map showing the top 50 mature miRNAs most significantly differentially expressed between matched Xp11 RCC tumors and normal samples (highlighted in cyan and red respectively in the figure). Hierarchical clustering was obtained using the Pearson’s distance and the average clustering method.

2.3. Technical and independent set validation of microarray findings

Among the most differentially expressed miRNAs from our microarray experiment, we selected miR-200c-3p and miR-34b-5p (up-regulated in tumors), and miR-222-3p (up-regulated in normal parenchyma) for technical validation using qRT-PCR. In this analysis we further included miR-21-5p (up-regulated in Xp11 RCC with a FDR of 6.5%), which has been associated with worse prognosis in RCC [24]. The consistency between microarray data and qRT-PCR data was 100% for all four miRNAs (Supplementary Figure S2A). In an additional independent set of 5 paired tumor and normal samples we found similar trends to those of the discovery set analyzed by microarray: up-regulation of miR-222 in tumors was consistent in 5/5 pairs, the down-regulation of miR-200c and the up-regulation of miR-21 were consistent in 4/5 pairs, while expression of miR-34b was coherent with microarray data in 3/5 samples (Supplementary Figure S2B).

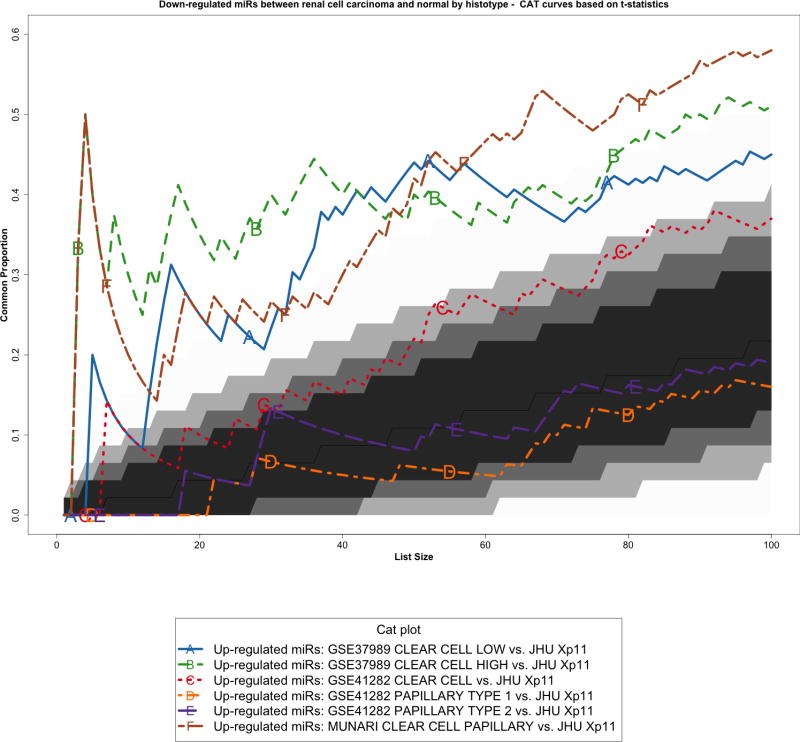

2.4. Meta-analysis of genome-wide miRNA expression profiling across RCC Subtypes

We re-analyzed three published studies (Munari et al, GSE37989, and GSE41282) as previously described [10] to identify miRNAs differentially expressed between tumor and normal samples in other types of RCC. We then performed a cross-platform comparison among these microRNA expression profiles using all 465 mature miRNAs in common among the different platforms (Supplementary Figure S3). In particular, we compared Xp11 RCC to clear cell papillary RCC (Munari et al dataset), clear cell RCC (both GSE37989 and GSE41282), and papillary RCC (GSE41282) at the global level using correspondence at the top (CAT) curves and Venn diagrams. Overall, CAT-curves based on moderated t-statistics derived from linear model analysis revealed that microRNA expression profiles obtained comparing tumor to normal renal parenchyma in Xp11 RCC more closely resemble those obtained in clear cell and in clear cell papillary RCC than those derived from papillary RCC (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S4). We used Venn diagrams to identify specific microRNA differentially expressed only in Xp11 RCC and not in the other RCC histological subtypes. This analysis revealed that among the most differentially expressed mature microRNA with FDR < 5%, 5 up-regulated (miR-148a-3p, miR-221-3p, miR-185-5p, miR-196b-5p, and miR-642a-5p) and 2 down-regulated (miR-133b, and miR-658) microRNAs were specific for Xp11 RCC (Supplementary Figure S5, Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Figure 3.

Correspondence at the top (CAT) curves for all up-regulated microRNAs in common between our Xp11 dataset and three previously published datasets encompassing distinct RCC subtypes (Munari et al, GSE37989, and GSE41282). Genes were ranked based on the moderated t-statistics obtained from our linear model analysis. Each CAT curve represents the proportion of differentially expressed microRNA in common between two expression profiles comparing tumor and normal samples. All microRNA expression profiles obtained from the different RCC groups analyzed using public domain data were compared to the one obtained using Xp11 RCC samples (reference profile). CAT curves in the white area above the gray shading indicate significant agreement, while the curves below indicate significant disagreement between expression profiles. The grey shading represents the 99.9% probability intervals of agreement by chance, therefore CAT curves in the white represent agreement beyond what it would be expected by chance alone. Overall we observed good agreement between Xp11 and clear cell papillary RCC, and between Xp11 and clear cell RCC.

2.5. Analysis of Functional Annotation in Xp11 RCC

Enrichment analysis of signaling pathways, functional themes, and biological concepts (Analysis of Functional Annotation, AFA) was performed to capture biological processes associated with Xp11 RCC microRNA expression profiles. We analyzed microRNA expression profiles obtained from our set of Xp11 RCC ordering genes based on the moderated t-statistics obtained from our linear model analysis. We separately investigated enrichment driven by microRNA differential expression, up-regulation, and down-regulation. FGS were associated to individual microRNA based on validated mRNA target information. Overall, FGS enrichment was exclusively driven by microRNA up-regulation in Xp11 tumors compared to normal samples, while no FGS proved to be significantly down-regulated (FDR < 5%). Table 2 summarizes the top 10 enriched FGS corresponding to signaling pathways as derived from KEGG, PANTHER, and WikiPathways databases most enriched in Xp11 RCC (complete results are reported in Supplementary Table S4).

Table 2.

Summary table for the top 10 most up-regulated signaling pathways (FDR < 0.001) as derived from the KEGG, PantherPath, and WikiPathways databases. Original p-values from Wilcoxon tests, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected q-values, and gene set sizes are shown.

| Gene Set Name | Value | Gene Set Size | Corrected Value | Ranking (within collection) | Description | Gene Set Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa03040_Spliceosome | 2.7 5E-07 |

158 | 5.38 E-05 |

1 | Gene set for Spliceosome | KEGG |

| hsa00310_Lysine degradation | 6.2 5E-07 |

91 | 6.13 E-05 |

2 | Gene set for Lysine degradation | KEGG |

| hsa04060_Cytokine cytokine receptor interaction | 1.0 9E-06 |

202 | 7.14 E-05 |

3 | Gene set for Cytokine cytokine receptor interaction | KEGG |

| hsa04114_Oocyte meiosis | 9.1 5E-06 |

181 | 0.00 04484 |

4 | Gene set for Oocyte meiosis | KEGG |

| hsa03018_RNA degradation | 1.5 7E-05 |

91 | 0.00 06031 |

5 | Gene set for RNA degradation | KEGG |

| hsa04110_Cell cycle | 1.8 5E-05 |

297 | 0.00 06031 |

5 | Gene set for Cell cycle | KEGG |

| hsa05010_Alzheimers disease | 6.2 7E-05 |

172 | 0.00 1754 |

7 | Gene set for Alzheimers disease | KEGG |

| hsa04340_Hedgehog signaling pathway | 7.9 5E-05 |

79 | 0.00 1912 |

8 | Gene set for Hedgehog signaling pathway | KEGG |

| hsa04914_Progesterone mediated oocyte maturation | 8.7 8E-05 |

192 | 0.00 1912 |

8 | Gene set for Progesterone mediated oocyte maturation | KEGG |

| hsa03030_DNA replication | 0.000 106 |

63 | 0.00 2022 |

10 | Gene set for DNA replication | KEGG |

| hsa04630_Jak STAT signaling pathway | 0.000 1135 |

198 | 0.00 2022 |

10 | Gene set for Jak STAT signaling pathway | KEGG |

| P00028_Heterotrimeric G protein signaling pathway rod outer segment phototransduction | 9.7 8E-06 |

41 | 0.00 03462 |

1 | Gene set for Heterotrimeric G protein signaling pathway rod outer segment phototransduction | PantherPath |

| P00040_Metabotropic glutamate receptor group II pathway | 1.6 7E-05 |

65 | 0.00 03462 |

1 | Gene set for Metabotropic glutamate receptor group II pathway | PantherPath |

| P00043_Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 2 and 4 signaling pathway | 1.6 8E-05 |

73 | 0.00 03462 |

1 | Gene set for Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 2 and 4 signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| P04373_5HT1 type receptor mediated signaling pathway | 8.5 3E-06 |

56 | 0.00 03462 |

1 | Gene set for 5HT1 type receptor mediated signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| P04377_Beta1 adrenergic receptor signaling pathway | 1.6 2E-05 |

53 | 0.00 03462 |

1 | Gene set for Beta1 adrenergic receptor signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| P04378_Beta2 adrenergic receptor signaling pathway | 1.6 2E-05 |

53 | 0.00 03462 |

1 | Gene set for Beta2 adrenergic receptor signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| P00039_Metabotropic glutamate receptor group III pathway | 2.8 2E-05 |

62 | 0.00 05 |

7 | Gene set for Metabotropic glutamate receptor group III pathway | PantherPath |

| P00057_Wnt signaling pathway | 8.8 8E-05 |

250 | 0.00 1376 |

8 | Gene set for Wnt signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| P00017_DNA replication | 0.000 3211 |

64 | 0.00 3244 |

9 | Gene set for DNA replication | PantherPath |

| P00048_PI3 kinase pathway | 0.000 3401 |

195 | 0.00 3244 |

9 | Gene set for PI3 kinase pathway | PantherPath |

| P00049_Parkinson disease | 0.000 3078 |

158 | 0.00 3244 |

9 | Gene set for Parkinson disease | PantherPath |

| P04374_5HT2 type receptor mediated signaling pathway | 0.000 2809 |

63 | 0.00 3244 |

9 | Gene set for 5HT2 type receptor mediated signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| P04380_Cortocotropin releasing factor receptor signaling pathway | 0.000 2732 |

45 | 0.00 3244 |

9 | Gene set for Cortocotropin releasing factor receptor signaling pathway | PantherPath |

| WP411_mRNA processing | 5.6 8E-06 |

167 | 0.00 08011 |

1 | Gene set for mRNA processing | WikiPathways |

| WP28_Selenium Metabolism and Selenoproteins | 1.8 9E-05 |

64 | 0.00 1329 |

2 | Gene set for Selenium Metabolism and Selenoproteins | WikiPathways |

| WP179_Cell cycle | 4.5 0E-05 |

276 | 0.00 1744 |

3 | Gene set for Cell cycle | WikiPathways |

| WP712_Estrogen signaling pathway | 4.9 5E-05 |

144 | 0.00 1744 |

3 | Gene set for Estrogen signaling pathway | WikiPathways |

| WP1984_Integrated Breast Cancer Pathway | 9.6 0E-05 |

222 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for Integrated Breast Cancer Pathway | WikiPathways |

| WP2037_Prolactin Signaling Pathway | 0.000 1921 |

212 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for Prolactin Signaling Pathway | WikiPathways |

| WP34_Ovarian Infertility Genes | 0.000 123 |

90 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for Ovarian Infertility Genes | WikiPathways |

| WP35_G Protein Signaling Pathways | 0.000 186 |

127 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for G Protein Signaling Pathways | WikiPathways |

| WP477_Cytoplasmic Ribosomal Proteins | 0.000 1638 |

163 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for Cytoplasmic Ribosomal Proteins | WikiPathways |

| WP500_Glycogen Metabolism | 0.000 149 |

68 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for Glycogen Metabolism | WikiPathways |

| WP536_Calcium Regulation in the Cardiac Cell | 0.000 1609 |

136 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for Calcium Regulation in the Cardiac Cell | WikiPathways |

| WP706_SIDS Susceptibility Pathways | 0.000 1571 |

119 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for SIDS Susceptibility Pathways | WikiP athw ays |

| WP707_DNA damage response | 0.000 1252 |

259 | 0.00 2083 |

5 | Gene set for DNA damage response | WikiPathways |

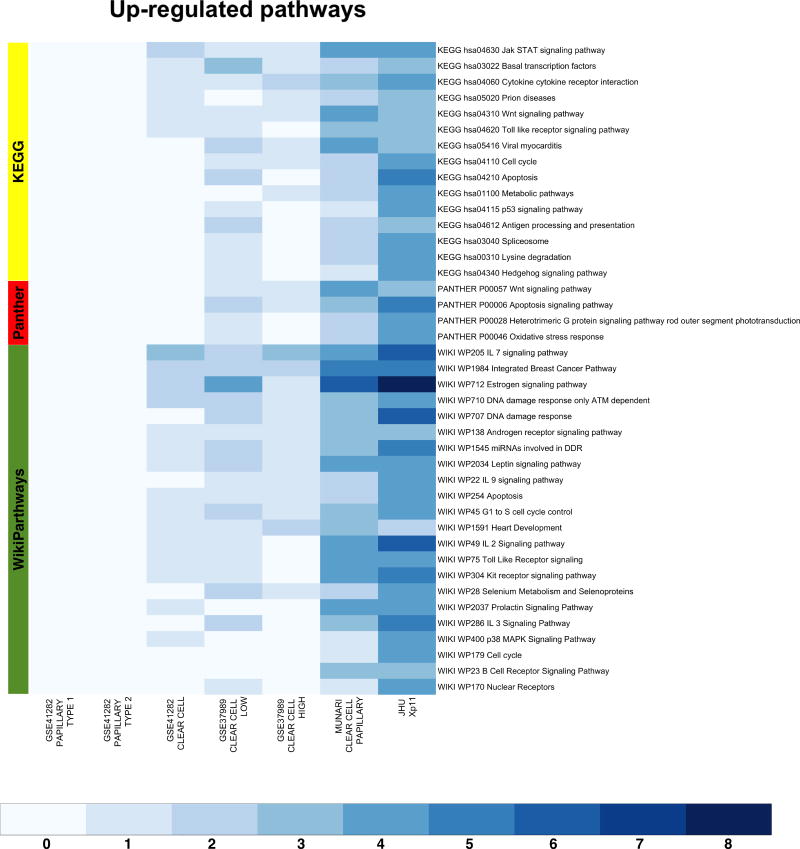

2.6. Analysis of Functional Annotation across RCC Subtypes

We also performed AFA on the microRNA expression profiles obtained using public domain data. To this end we restricted the enrichment analysis to the set of microRNAs in common across all datasets (Supplementary Figure S3). This allowed us comparing biological concepts and pathways enriched in Xp11 RCC to those enriched in the other RCC subtypes analyzed using public domain data. We selected the most up-regulated pathways (FDR < 0.00025%) in any considered comparisons between tumor and normal samples. This analysis revealed a common set of relevant enriched pathways (especially between Xp11, clear cell, and clear cell papillary tumors, see Figure 4), like the Jak STAT signaling pathway (KEGG hsa40630), the Wnt signaling pathway (KEGG hsa04310, PANTHER P00057), the estrogen signaling pathways (WIKI WP712), and several immune signaling pathways (Figure 4). Similarly, we also identified a set of biological themes most strongly associated with Xp11 tumors, like a set of FGS related to the DNA damage response pathways (WIKI WP707 and WP710), cell cycle progression (Wiki WP45 and WP179, KEGG hsa04210), apoptosis (Wiki WP254, KEGG hsa04210, and PANTHER P00006), and several metabolic processes (Figure 4). The comparison of findings from AFA across multiple datasets and histologic types further confirmed the resemblance of Xp11 RCC to the clear cell phenotype at the molecular level.

Figure 4.

Heat-maps visualizing up-regulated functional gene sets (FGS) as determined by Analysis of Functional Annotation (AFA) performed on microRNAs expression profiles associated with Xp11 and other types of RCC. Each row represents a distinct FGS, while each column represents a distinct coefficient from our linear model analysis. The FGS that were most significantly up-regulated across any comparison performed are shown in the figure (FDR ≤ 0.00025%, or less). Color scales correspond to the absolute adjusted p-values obtained from our analysis after base 10 logarithmic transformations (i.e., the number on the color scale increases with decreasing FDR). Up-regulated FGS were selected from different collections to capture signaling pathways and biological themes modulated by microRNA expression in RCC. The databases used are highlighted on the left: PantherPath in red, KEGG in green, and WikiPathways in yellow. Complete tables with results from enrichment test are reported in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2 (also available at http://luigimarchionni.org/Xp11RCC.html).

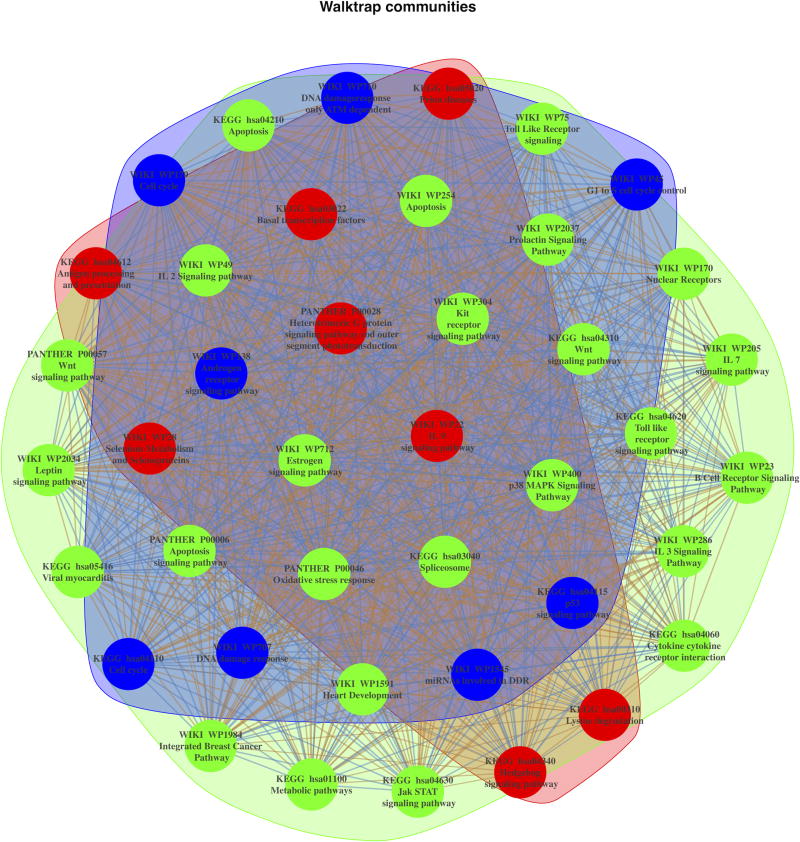

2.7. Social network analysis of biological concepts associated with Xp11RCC

We used social network analysis to analyze the relationships among the most up-regulated signaling pathways (FDR < 00025%) identified through AFA and to pinpoint the microRNA modules driving such enrichment. This analysis revealed three distinct pathway modules sharing distinct up-regulated microRNAs (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure S6). The first set accounted for pathways involved in cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, and apoptosis (Figure 5, community highlighted in blue); the second set grouped most FGS related to cytokines and cancer related signaling pathways (Figure 5, community highlighted in green); the third set accounted for FGS related several metabolic processes and the Hedgehog signaling pathway (Figure 5, community highlighted in red). Hierarchical clustering depicting such groupings is shown in Supplementary Figure S6.

Figure 5.

Social network analysis of FGS up-regulated in Xp11 and other RCC subtypes. The figure depicts the weighted undirected network based on the up-regulated microRNA in common among the enriched FGS from Figure 4. In the network vertexes represent specific FGS, while the edges (and their weights) are based on the number of up-regulated microRNA in common among the FGS. Three distinct FGS “communities” (i.e., subgraphs of FGS sharing common subset of microRNAs) were identified using the community search method based on random walks implemented by Pons et al [23] and are shown in the figure with distinct colors.

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the miRNA expression profiles of Xp11 translocation RCC compared to matched normal renal parenchyma. We further compared these expression profiles with those associated with other RCC subtypes as available from three publically available datasets, identifying common and distinctive patterns of microRNA expression in Xp11 RCC. We validated our microarray findings by quantitative RT-PCR analysis in all cases analyzed by microarray and in additional five independent tumor-normal pairs. We further characterized the molecular pathways and biological themes associated with such common and distinctive microRNA profiles using AFA. Finally, we used social network analysis to identify groups of pathways and biological processes collectively regulated by distinct microRNA expression modules. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing miRNAs regulation in Xp11 as well as in other RCC subtypes.

Among the most differentially expressed miRNAs, several proved to be up-regulated in more than one study across different RCC subtypes (e.g., miR-15a-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-34b-5p, hsa-miR-342-3p, and miR-339-5p, Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S2). These microRNA molecules could serve as general markers for RCC irrespective to histologic type or molecular underpinning. For instance, miR-15a has already shown to be up-regulated in RCC compared to benign oncocytomas and to be part of a gene regulatory network involving NF-κB, p65, the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38alpha, and the protein kinase C alpha [25]. Similarly, also miR-34a has been shown to be up-regulated in RCC across different morphologic and molecular subtypes [10,26], with a possible role in suppressing cell invasion by targeting c-MYC in clear cell RCC cell lines [27]. Finally, miR-339-5p has been recently identified as a regulator of the p53 pathway by reducing MDM2 expression hence promoting p53 function [28]. Overall the pathogenic significance, if any, of the up-regulation of these microRNAs in RCC should be further explored.

Similarly, a number of other microRNA molecules were down-regulated in more than one study across different RCC subtypes (e.g., miR-200c-3p and miR-141-3p, Supplementary Table S3). These microRNAs molecules have been previously and consistently shown to be down-regulated in RCC, and they have implicated in modulating the vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) target [10,29]. Finally, the down-regulation of miR-200c-3p, a member of the miR-200 family that regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression [30], is in line with previous reports in renal cancer [31].

Among the most differentially expressed miRNAs specific for Xp11 RCC, we found miR-148a-3p, miR-221-3p, miR-185-5p, miR-196b-5p, and miR-642a-5p to be up-regulated, while miR-133b and miR-658 were down-regulated compared to normal renal parenchyma. The aberrant expressions of miR-148a and miR-133b have been in shown in various cancers with both oncogenic or tumor suppressor roles through targeting important cancer genes and the modulation of key mechanisms involved in tumor initiation and progression [32,33]. Among the other microRNA specific for Xp11 tumors, miR-221-3p and miR-185-5p were reported to be differentially expressed, although inconsistently, in clear cell RCC [34,35].

Overall, our study also revealed that, in terms of global miRNA expression profiles, Xp11 translocation RCCs most closely resembled clear cell papillary RCC, that they were least close to papillary RCC, and that they showed an intermediate agreement with tumors of clear cell histology. While the strong agreement with the clear cell papillary histologic type may be due to the fact that the analysis was carried out on the same microarray platform, the comparison within the GSE41282 dataset, which accounts for both clear cell and papillary cases [17], clearly showed that at the molecular level Xp11 translocation RCCs more closely resemble clear cell than papillary RCCs. Overall this trend was further confirmed at the pathway level with important cancer and immune signaling pathways similarly deregulated in Xp11, clear cell, and clear cell papillary RCC. Of note, microRNA expression profiles of Xp11 RCC also displayed a stronger deregulation of pathway controlling DNA damage response, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we presented the first comprehensive analysis of miRNA expression profiles of Xp11 RCC. Overall our results might help in understanding the molecular underpinning of this type of tumor. We found evidence that this RCC molecular subtype, while sharing some overlap with clear cell and clear cell papillary RCC, it also shows a unique pattern of miRNA expression affecting specific cellular functions, supporting the notion this is a separate molecular and biological entity with potentially important implications for therapy development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was in part made possible through support from the Dahan Translocation Carcinoma Fund and Joey’s Wings (PA), the NIH-NCATS grant UL1TR001079 (LM), and the NIH-NCI grant R01CA200859 (LM)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors do not have conflict of interests to declare

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Argani P. MiT family translocation renal cell carcinoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2015;32:103–13. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argani P, Zhong M, Reuter VE, Fallon JT, Epstein JI, Netto GJ, et al. TFE3-Fusion Variant Analysis Defines Specific Clinicopathologic Associations Among Xp11 Translocation Cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:723–37. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argani P, Antonescu CR, Couturier J, Fournet J-C, Sciot R, Debiec-Rychter M, et al. PRCC-TFE3 renal carcinomas: morphologic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and molecular analysis of an entity associated with the t(X;1)(p11. 2;q21) Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1553–66. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green WM, Yonescu R, Morsberger L, Morris K, Netto GJ, Epstein JI, et al. Utilization of a TFE3 break-apart FISH assay in a renal tumor consultation service. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1150–63. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828a69ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sukov WR, Hodge JC, Lohse CM, Leibovich BC, Thompson RH, Pearce KE, et al. TFE3 rearrangements in adult renal cell carcinoma: clinical and pathologic features with outcome in a large series of consecutively treated patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:663–70. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824dd972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis CL, Eble JN, Subhawong AP, Martignoni G, Zhong M, Ladanyi M, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma: impact of fusion subtype, age, and stage. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:875–86. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argani P, Hicks J, De Marzo AM, Albadine R, Illei PB, Ladanyi M, et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma (RCC): extended immunohistochemical profile emphasizing novel RCC markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1295–303. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e8ce5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuda M, Davis IJ, Argani P, Shukla N, McGill GG, Nagai M, et al. TFE3 fusions activate MET signaling by transcriptional up-regulation, defining another class of tumors as candidates for therapeutic MET inhibition. Cancer Res. 2007;67:919–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malouf GG, Su X, Yao H, Gao J, Xiong L, He Q, et al. Next-generation sequencing of translocation renal cell carcinoma reveals novel RNA splicing partners and frequent mutations of chromatin-remodeling genes. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4129–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munari E, Marchionni L, Chitre A, Hayashi M, Martignoni G, Brunelli M, et al. Clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: micro-RNA expression profiling and comparison with clear cell renal cell carcinoma and papillary renal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross AE, Marchionni L, Phillips TM, Miller RM, Hurley PJ, Simons BW, et al. Molecular effects of genistein on male urethral development. The Journal of Urology. 2011;185:1894–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho C-Y, Bar E, Giannini C, Marchionni L, Karajannis MA, Zagzag D, et al. MicroRNA profiling in pediatric pilocytic astrocytoma reveals biologically relevant targets, including PBX3, NFIB, and METAP2. Neuro-Oncology. 2013;15:69–82. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iglesias-Ussel M, Vandergeeten C, Marchionni L, Chomont N, Romerio F. High Levels of CD2 Expression Identify HIV-1 Latently Infected Resting Memory CD4+ T Cells in Virally Suppressed Subjects. J Virol. 2013;87:9148–58. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01297-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leek JT, Storey JD. Capturing heterogeneity in gene expression studies by surrogate variable analysis. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1724–35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wach S, Nolte E, Theil A, Stöhr C, Rau T, Hartmann A, et al. MicroRNA profiles classify papillary renal cell carcinoma subtypes. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:714–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wotschofsky Z, Liep J, Meyer H-A, Jung M, Wagner I, Disch AC, et al. Identification of metastamirs as metastasis-associated microRNAs in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1363–74. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross AE, Marchionni L, Vuica-Ross M, Cheadle C, Fan J, Berman DM, et al. Gene expression pathways of high grade localized prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;71:1568–77. doi: 10.1002/pros.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kortenhorst MS, Wissing MD, Rodriguez R, Kachhap SK, Jans JJ, Van der Groep P, et al. Analysis of the genomic response of human prostate cancer cells to histone deacetylase inhibitors. Epigenetics. 2013:8. doi: 10.4161/epi.25574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dweep H, Gretz N. miRWalk2. 0: a comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Meth. 2015;12:697–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pons P, Latapy M. Computing Communities in Large Networks Using Random Walks. Jgaa. 2006;10:191–218. doi: 10.7155/jgaa.00124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu L, Li H, Chen L, Ma X, Gao Y, Li X, et al. MicroRNAs as prognostic molecular signatures in renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32545–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandenstein von M, Pandarakalam JJ, Kroon L, Loeser H, Herden J, Braun G, et al. MicroRNA 15a, inversely correlated to PKCα, is a potential marker to differentiate between benign and malignant renal tumors in biopsy and urine samples. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1787–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osanto S, Qin Y, Buermans HP, Berkers J, Lerut E, Goeman JJ, et al. Genome-wide microRNA expression analysis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma by next generation deep sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamura S, Saini S, Majid S, Hirata H, Ueno K, Chang I, et al. MicroRNA-34a suppresses malignant transformation by targeting c-Myc transcriptional complexes in human renal cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:294–300. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansson MD, Damas ND, Lees M, Jacobsen A, Lund AH. miR-339-5p regulates the p53 tumor-suppressor pathway by targeting MDM2. Oncogene. 2015;34:1908–18. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakada C, Matsuura K, Tsukamoto Y, Tanigawa M, Yoshimoto T, Narimatsu T, et al. Genome-wide microRNA expression profiling in renal cell carcinoma: significant down-regulation of miR-141 and miR-200c. J Pathol. 2008;216:418–27. doi: 10.1002/path.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davalos V, Moutinho C, Villanueva A, Boque R, Silva P, Carneiro F, et al. Dynamic epigenetic regulation of the microRNA-200 family mediates epithelial and mesenchymal transitions in human tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2012;31:2062–74. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wotschofsky Z, Busch J, Jung M, Kempkensteffen C, Weikert S, Schaser KD, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of differentially expressed miRNAs between metastatic and non-metastatic renal cell carcinoma at the time of nephrectomy. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;416:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Enokida H, Seki N. microRNA-1/133a and microRNA-206/133b clusters: dysregulation and functional roles in human cancers. Oncotarget. 2012;3:9–21. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Deng X, Zeng X, Peng X. The Role of Mir-148a in Cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7:1233–41. doi: 10.7150/jca.14616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrozza V, Carbone A, Bellissimo T, Porta N, Palleschi G, Pastore AL, et al. Oncogenic MicroRNAs Characterization in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:29219–25. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Brannon AR, Reddy AR, Alexe G, Seiler MW, Arreola A, et al. Identifying mRNA targets of microRNA dysregulated in cancer: with application to clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:51. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.