Abstract

Panax ginseng is one of the most universally used herbal medicines in Asian and Western countries. Most of the biological activities of ginseng are derived from its main constituents, ginsenosides. Interestingly, a number of studies have reported that ginsenosides and their metabolites/derivatives—including ginsenoside (G)-Rb1, compound K, G-Rb2, G-Rd, G-Re, G-Rg1, G-Rg3, G-Rg5, G-Rh1, G-Rh2, and G-Rp1—exert anti-inflammatory activities in inflammatory responses by suppressing the production of proinflammatory cytokines and regulating the activities of inflammatory signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor-κB and activator protein-1. This review discusses recent studies regarding molecular mechanisms by which ginsenosides play critical roles in inflammatory responses and diseases, and provides evidence showing their potential to prevent and treat inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: ginsenosides, inflammation, inflammatory diseases, Panax ginseng, signaling

1. Introduction

The immune response is the most important defense system protecting the human body from external attacks by microorganisms and toxic chemical compounds. In order for this function to work properly, it is necessary to distinguish pathogens from the body's own cells or tissues. However, pathogens can avoid the immune system through various mechanisms. Therefore, multiple approaches that recognize and neutralize pathogens have been developed to overcome these difficulties. The immune system uses a layered defense strategy against infection based on gradually increasing specificity for invading organisms [1]. Innate immunity is the first line of defense, composed of four kinds of barriers: physical, physiological, phagocytosis, and inflammation (Table 1). Innate immunity acts mainly to detect invading microorganisms by recognizing their pathogen-associated molecular patterns [2], and therefore acts in a comprehensive manner against pathogens. In addition, the immune response is not long-lasting [3]. Adaptive immunity, also known as acquired immunity, is the second line of defense and has two important processes that are distinguished from those of innate immunity: presenting antigens and developing immunological memory (Table 2) [4]. Adaptive immunity is divided into two types of immune responses: humoral immune response and cell-mediated immune response [5]. The humoral immune response is mediated by antibodies produced by B cells in body fluids, which collaborate with complements secreted by hepatocytes or macrophages [4], [6]. The cell-mediated immune response refers to the process in which immune cells detect and destroy nonself cells [7], and consists of two responses. Of the two, the antigen-specific reaction is caused by cytotoxic T cells that are produced to destroy antigen-displaying cells by recognizing major histocompatibility complex class I molecule- and endogenous antigen-presenting cells, whereas nonspecific reactions take place when major histocompatibility complex class II molecules and exogenous antigens are presented on the cell membrane. In this response, helper T cells are produced and secrete interleukins and cytokines to stimulate B cells [8]. In turn, the stimulated B cells produce antigen-specific antibodies and activate natural killer cells and macrophages to eliminate the infected cells [9].

Table 1.

The four barriers of innate immunity

| Physical barriers | Skin | Skin epidermis prevents pathogen invasion Skin pH maintained between 3 and 5 by sebum to inhibit growth of pathogens |

| Mucosal membrane | Mucosal membrane traps pathogens | |

| Physiological barriers | Temperature | Temperature affects survival of invading pathogens |

| pH | Acidic environment of stomach kills pathogens | |

| Chemical mediators | Lyse cell walls of invading pathogens | |

| Phagocytosis | Neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells | |

| Inflammation | Clearing invading pathogens via complex events |

|

Table 2.

Innate versus adaptive immunity

| Innate immunity | Adaptive immunity | |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Broad specificity | Narrow specificity |

| Memory | Absent | Present (amplified in second response) |

| Cells | Macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophil cells | B and T lymphocytes |

| Reaction time | Immediate response | Delayed response |

| Receptors | Encoded in the germline (LPS receptor, N-formyl methionyl receptor, mannose receptor, and scavenger receptor) |

Encoded by somatic genes diversified by somatic recombination (TCR, Ig) |

Ig, immunoglobulin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TCR, T cell receptor.

Ginseng, a perennial plant belonging to genus Panax, family Araliaceae, has been used as a popular herbal medicine for thousands of years. Ginseng is known to promote vitality, prolong life, and show effects against a variety of conditions, including depression, diabetes, fatigue, aging, inflammation, internal degeneration, nausea, tumors, pulmonary problems, dyspepsia, vomiting, nervousness, stress, and ulcers [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. There are up to 13 plants affiliated with the genus Panax, with just five of them used therapeutically: Panax ginseng, American ginseng, Vietnamese ginseng, Japanese ginseng, and Pseudoginseng. Among these five, P. ginseng is most commonly used for the purpose of treatment, being used in 16.6% of 3,944 prescriptions reported in the Korean Clinical Pharmacopoeia, written in 1610 a.d. [15]. The pharmacological effects of ginseng are derived from multiple active ingredients, including ginsenosides, ginsengosides, polysaccharides, peptides, phytosterols, polyacetylenes, polyacetylenic alcohols, and fatty acids [16], [17].

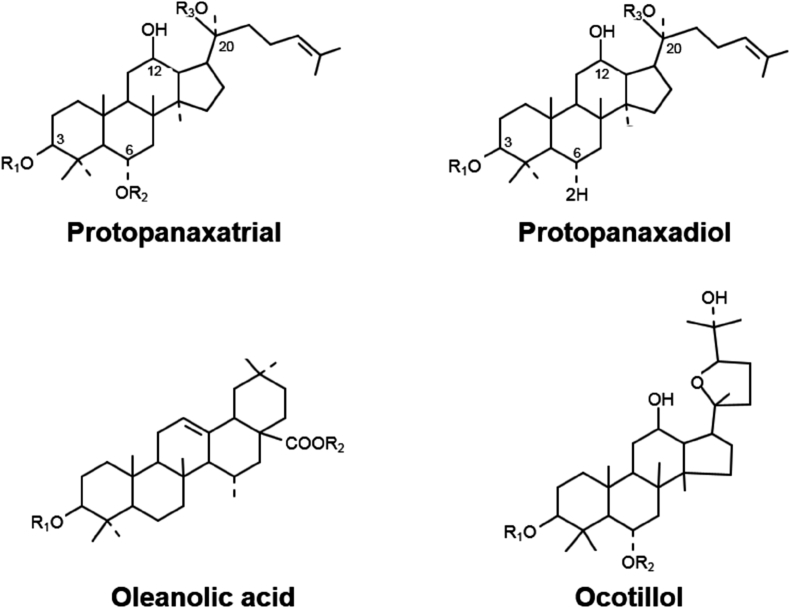

The ginsenosides are the major active pharmacological components of ginseng [18]. Ginsenosides, also known as steroid-like saponins, are unique to ginseng species. There are more than 100 ginsenosides, which are expressed by Rx. The X is determined by the distance of movement on a thin-layer chromatography plate in vitro: the most polar segment is marked A, whereas the least polar is H [19]. Ginsenosides are classified into four groups based on their backbone types (Fig. 1). Diverse sugar molecules are attached to different areas of the four backbones to produce distinctive ginsenoside molecules (Table 3). Various studies have been conducted to understand the pharmacological mechanisms of ginseng and ginsenosides in cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, cancers, stress, and immunostimulation [18]. The anti-inflammatory role of ginseng, however, remains poorly understood. Therefore, the pharmacological functions of ginseng and ginsenosides in inflammatory responses are discussed in this review.

Fig. 1.

Classification of ginsenosides based on backbone types.

Table 3.

Classification of ginsenosides

| Class | Backbone type | Representative ginsenosides |

|---|---|---|

| Protopanaxadiol type | Dammarane backbone | Ginsenoside-Ra1-3, G-Rb1-2, and G-Rh2-3 |

| Protopanaxatriol type | Additional hydroxyl group on C6 in a dammarane backbone | Ginsenoside-Re, G-Rf, and G-Rg1 |

| Oleanolic acid type | Pentacyclic triterpenoid base | Ginsenoside-Ro |

| Ocotillol type | Five-membered epoxy ring at C20 | Makonoside-Rs from Vietnamese ginseng |

2. Inflammatory responses and cytokines

Inflammation is a protective response of the body to remove harmful stimuli, including damaged cells, pathogens, and irritants [20], and is one of the physical barriers of innate immunity. Infection by pathogens is a main cause of inflammatory responses, but injury or trauma (in the absence of parasitic infection) and exposure to foreign particles, irritants, and pollutants are also potent inducers of inflammation [21]. Inflammation is a well-orchestrated biological reaction that consists of multiple steps. The first step is the recognition of external stimuli. This is mainly achieved by germ-line encoded receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and leucine-rich-repeat-containing receptors (NLRs) [22], [23], [24]. These receptors detect pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns, then activate receptors to stimulate a series of signaling cascades, including nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) pathways. These transcriptional factors induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). Consequently, cytokines facilitate the recruitment of effector immune cells to the site of inflamed tissue, and in turn, these effector cells create a cytotoxic environment to remove the invading pathogens by releasing toxic chemicals, including highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species.

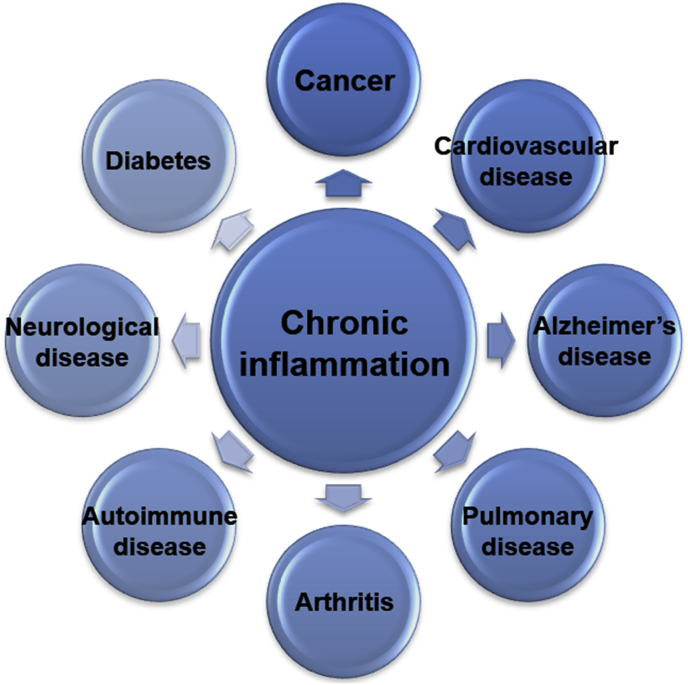

Inflammation is essential to restore tissue homeostasis, and therefore may cause serious diseases when it is not tightly regulated. For example, genetic deficiencies in primary regulators of inflammation increase susceptibility to infection in humans, such as neutropenia. A study using knockout mice revealed that defects in proinflammatory cytokines and effector-encoding genes increase the risk of severe infection [25]. In contrast, immoderate inflammation results in devastating impacts by causing unnecessary collateral damage. An example corresponding to this effect is chronic inflammation, in which acute inflammation persists for more than 4 weeks. Chronic inflammation is caused by persistent injury or infection, prolonged exposure to a toxic agent, or autoimmune disease, which can induce various diseases, such as cancer and diabetes (Fig. 2) [26], [27], [28], [29].

Fig. 2.

Diseases associated with chronic inflammation.

3. Anti-inflammatory effects of ginsenosides

3.1. Ginsenoside-Rb1

Ginsenoside-Rb1 (G-Rb1), a main component of P. ginseng, inhibits TNF-α production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages, indicating that G-Rb1 is a potential anti-inflammatory agent [30], [31]. G-Rb1 also suppresses the activation of NF-κB, which is a key regulator of inflammation, as well as a controller of TNF-α production in LPS-activated murine peritoneal macrophages [32]. The activation of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-1, an inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK)-α, NF-κB, and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), is also significantly decreased by G-Rb1. However, G-Rb1 does not affect the interaction between LPS and TLR4 and the activation of IRAK-4 and IRAK-2 [32]. In addition, G-Rg1 exhibits in vivo anti-inflammatory effects in a 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfuric acid (TNBS)-induced colitis animal model by inhibiting IRAK activation-mediated inflammatory responses [32].

Osteoporosis is a bone loss disease characterized by decreased bone strength and increased bone fragility [33]. Osteoporosis occurs as a result of a variety of endocrine, metabolic, and mechanical factors [34]. However, the influence of inflammation on bone turnover has also emerged. In particular, inflammatory diseases such as immunological dysfunctions, autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases, HIV infection, hyper-immunoglobulin E (IgE) syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, hematological diseases (particularly myeloma), and inflammatory bowel diseases are related to osteoporosis [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. Inflammation mainly regulates bone remodeling through two mechanisms [40]. (1) Proinflammatory cytokines play roles as final regulators of osteoclast function. For example, the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), also known as TNF-related activation-induced cytokine, belongs in this category. (2) Regulation of macrophage colony stimulating factor controls osteoclastogenesis [41]. Interestingly, G-Rb1 exerts antiosteoporotic activity by inhibiting the RANKL-stimulated osteoclast differentiation from RAW264.7 macrophages. G-Rb1 suppresses RANKL-induced c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), p38 MAPK, and NF-κB pathways, and consequently blocks the expression of c-Fos and NF of activated T cells (NFAT) C1, which are essential factors for the differentiation of osteoclasts [42].

3.2. Compound K

Compound K (CK), a bacterial metabolite of G-Rb1, exhibits anti-inflammatory effects mainly by reducing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, and proinflammatory cytokines [32], [43], [44]. CK suppresses the expression of proinflammatory cytokines by downregulating the activities of IRAK-1, MAPKs, IKK-α, and NF-κB in LPS-treated murine peritoneal macrophages [32]. CK also suppresses the expression of iNOS and COX-2 by inhibiting NF-κB signaling in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells [45]. In zymosan-treated bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) and RAW264.7 cells, CK inhibits inflammatory responses by negatively regulating the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, the activation of MAPKs, and the generation of ROS [43]. In addition, anti-inflammatory activity of CK has been observed in LPS-stimulated microglial cells. CK hinders inflammatory responses by controlling both the generation of ROS and the activities of MAPKs, NF-κB, and AP-1 [44].

The anti-inflammatory activities of CK have been explored in a variety of inflammation-associated animal models. CK downregulates 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced ear edema by regulating the activities of NF-κB and COX-2 [46]. CK negatively regulates intestinal inflammation by modulating NF-κB signaling in both a TNBS-induced colitis animal model and a dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis animal model [32], [47]. Moreover, CK protects mice from endotoxin-induced lethal shock by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines [43], [48].

3.3. Ginsenoside-Rb2

Ginsenoside-Rb2 (G-Rb2) significantly inhibits the production of TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and differentiated U937 cells with IC50 values of 27.5 μM and 26.8 μM, respectively [31]. In addition, G-Rb2 has been reported to exert neuroprotective effects in LPS-stimulated N9 microglial cells by blocking TNF-α production [49]. G-Rb2 inhibits activation of IκBα, indicating that G-Rb2-mediated downregulation of TNF-α production in microglia is achieved by NF-κB inhibition, which may be a basic mechanism for the anti-inflammatory activity of G-Rb2 [49].

3.4. Ginsenoside-Rd

Ginsenoside-Rd (G-Rd) has also shown neuroprotective effects. Similar to G-Rb2, G-Rd also suppresses LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation and TNF-α expression in N9 cells [49]. In addition, G-Rd exerts neuroprotective effects in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia by regulating an early free radical scavenging pathway and a late anti-inflammatory response. G-Rd also decreases the formation of hydroxyl radicals, the early accumulation of DNA and protein, and lipid peroxidation. G-Rd suppresses inflammatory responses in later stages after ischemia by the inhibiting the expression of iNOS and COX-2 [50]. Moreover, G-Rd deceases inflammatory responses in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells. G-Rd reduces NO generation, PGE2 production, and NF-κB activity [51].

3.5. Ginsenoside-Re

Ginsenoside-Re (G-Re) shows anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting interactions between LPS and TLR4 on macrophages. G-Re suppresses LPS-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of IRAK-1, and sequentially blocks IKK-α phosphorylation, NF-κB activation, and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β [52].

LPS-induced inflammatory response is closely associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease (AD), and multiple sclerosis. It has been known that LPS activates microglial cells in the central nervous system [53], [54]. G-Re exerts a protective effect against neuroinflammation in the central nervous system by inhibiting proinflammatory mediators (iNOS and COX2) generated by LPS and blocking the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in BV2 microglial cells, indicating that G-Re could be a promising medication to treat neuroinflammatory diseases [55]. G-Re is curative in a TNBS-induced colitis mouse model. Oral administration (20 mg/kg) of G-Re is effective against LPS-induced systemic inflammation in a TNBS-induced colitis mouse model. G-Re dramatically inhibits the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α, as well as NF-κB activation, and suppresses colon shortening and myeloperoxidase activity in a colitis mouse model [52].

3.6. Ginsenoside-Rg1

Ginsenoside-Rg1 (G-Rg1) modulates microglial activation, which plays a critical role in neurodegenerative diseases. G-Rd1 negatively regulates the production of TNF-α and NO as well as the expression of iNOS and ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1) by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs pathways in mice when LPS is intracerebroventricularly injected [56]. In accordance, G-Rg1 also suppresses the expression of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB in LPS-stimulated BV-2 microglial cells. Interestingly, PLC-γ1 inhibitor partially eliminates the suppressive effect of G-Rg1 in the LPS-mediated activation of IκB-α, cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), JNK, and p38 MAPK, indicating that PLC signaling may be associated with the inhibitory activity of G-Rb1 for microglial activation [57], [58]. The inhibitory activity of G-Rg1 on inflammation has also been examined in macrophages. G-Rg1 suppresses the expression of both IL-6 mRNA and protein by inhibiting the NF-κB signal pathway in both LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophages. In contrast, G-Rb1 increases TNF-α expression by activating the mTOR signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated macrophages [59]. These results strongly suggest that G-Rg1 plays a pivotal role in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses with different modes of actions by modulating signaling pathways of NF-κB or Akt/mTOR. In vivo anti-inflammatory function of G-Rg1 has also been demonstrated in inflammatory animal models. G-Rg1 effectively ameliorates the symptoms of alcoholic hepatitis and TNBS-induced colitis in animal models by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, as consistently observed in vitro [60], [61].

Recently, it was reported that G-Rb1 protects diverse tissues from ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury by regulating inflammatory response and apoptosis. G-Rb1 protects the liver against IR injury in rats by modulating NF-κB and ROS–NO–hypoxia-inducible factor signaling pathways [62], [63]. Cerebral IR injury is also ameliorated by G-Rb1 activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) or suppressing protease-activated receptor-1 expression in rat hippocampus [64], [65]. Moreover, G-Rg1 shows a protective effect against cerebral IR injury by modulating the activation of p38 MAPK [66]. These results suggest that G-Rg1 has therapeutic potential for IR injury.

3.7. Ginsenoside-Rg3

Ginsenoside-Rg3 (G-Rg3) shows suppressive effects in neurodegenerative conditions by preventing inflammatory neurotoxicity and microglial activation. G-Rg3 significantly suppresses TNF-α expression and NF-κB activation in Abeta42-activated BV-2 microglial cells. The survival rate of TNF-α-treated Neuro-2a cells increased after pretreatment with G-Rg3 [67]. In addition, daily administration of G-Rg3 for 21 days significantly improves learning and memory impairments induced by LPS injection into rat brains by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory mediators in the hippocampus [68].

Recent studies have reported the role of G-Rg3 in inflammasome activation. Two optical isomers of G-Rg3, 20(R)-Rg3 and 20(S)-Rg3, exhibit inhibitory effects on both S-nitrosylation of the nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat-containing receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and lethal endotoxin-induced shock by suppressing iNOS [69], whereas 20(R)-Rg3 and 20(S)-Rg3 suppress NO generation and iNOS expression. S-nitrosylation of the NLRP3 inflammasome proteins, such as NLRP3 and caspase-1, is decreased by these G-Rg3 isomers in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs. Under long-term LPS exposure, LPS-generates excessive NO that inhibits IL-1β production by inducing inflammasome activation and Akt phosphorylation. However, 20(R)-Rg3 and 20(S)-Rg3 prevent this event by blocking the excessive generation of NO. Moreover, 20(R)-Rg3 and 20(S)-Rg3 reduce susceptibility to lethal endotoxin shock by modulating the generation of NO in LPS-injected mice, strongly indicating that these two optical isomers of G-Rg3 might be useful in therapeutic approaches to treat oxidative stress-related diseases [69].

3.8. Ginsenoside-Rg5

Anti-inflammatory effects of ginsenoside-Rg5 (G-Rg5), a main component of steamed ginseng, have been studied in the context of lung inflammation. G-Rg5 reduces the expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, COX-2, and iNOS, and phosphorylation of IRAK-1, IKK-α, and NF-κB. The degradation of IRAK-1 and IRAK4 are decreased by G-Rg5 in LPS-stimulated alveolar macrophages [70]. According to an experiment using Alexa Flour 594-conjugated LPS, G-Rg5 interferes with the binding of LPS to macrophages. The expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS, and COX-2, as well as the activation of NF-κB are also suppressed by G-Rg5 (10 mg/kg) in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of LPS-injected mice [70]. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory activity of G-Rg5 has been observed in TNF-α-stimulated liver cells, and in HepG2 cells by inhibiting NF-κB, COX-2, and iNOS (IC50 = 0.61) [71].

Inhibitory effects of G-Rg5 in neuroinflammatory responses have also been examined in a memory-impaired rat model induced by streptozotocin (STZ). In particular, because cholinergic system synthases such as choline acetyltransferase, hydrolytic enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase, and imbalanced levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are associated with impaired memory function, the regulatory effect of G-Rg5 on these molecules was investigated. G-Rg5 improves cognitive deficits by downregulating AChE activity and upregulating choline acetyltransferase activity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of STZ-induced AD rats. Administration of 10 and 20 mg/kg of G-Rg5 significantly increased the expression of BDNF and IGF-1 in the brain tissue of AD rats. Moreover, amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition was decreased in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of diseased rats. G-Rg5 suppresses STZ-induced expression of COX-2 and iNOS, which are key inflammatory enzymes in neuroinflammation [72]. In addition, a protective effect of G-Rg5 has been observed in scopolamine-induced memory impaired mice. In this model, G-Rg5 improves memory deficits by suppressing AChE activity and increasing BDNF expression and CREB phosphorylation [73]. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that G-Rg5 is a potential drug candidate to treat AD.

Anti-inflammatory activity of G-Rg5 in skin tissue was also investigated in in vitro atopic dermatitis models, such as TNF-α/IFN-γ-treated keratinocytes and LPS-stimulated macrophages. G-Rg5 dramatically inhibits the expression of thymus- and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) in TNF-α/IFN-γ-stimulated HaCaT cells. LPS-induced generation of NO and ROS is also decreased by G-Rg5 in RAW264.7 cells. In addition, G-Rg5 suppresses NF-κB/p38 MAPK/STAT1 signaling pathways, which are critically involved in TARC/CCL17 expression and NO production [74]. These results indicate that G-Rg5 exerts anti-inflammatory activity in skin disease by blocking the NF-κB/p38 MAPK/STAT1 signal pathways.

3.9. Ginsenoside-Rh1

The anti-inflammatory effects of ginsenoside-Rh1 (G-Rh1) act mainly by suppressing the expression of COX-2 and iNOS [75], [76]. In particular, the molecular mechanism of G-Rh1-mediated iNOS inhibition is well demonstrated in microglial cells. In IFN-γ-stimulated BV2 microglial cells, G-Rh1 inhibits the activation of Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT and ERK signaling and their downstream transcriptional factors, including NF-κB, IRF-1, and STAT1, thereby suppressing iNOS expression and neuroinflammation [76].

The inhibitory activity of G-Rh1 on oxazolone-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in hairless mice has also been investigated. G-Rh1 diminishes the serum levels of IgE and IL-6 in atopic dermatitis-induced mice, and consequently, the infiltration of inflammatory cells and granulation of mast cells significantly decrease. Furthermore, G-Rh1 (10 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg) improves the symptoms of atopic dermatitis and ear swelling [77], suggesting that G-Rh1 has potential as an anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

3.10. Ginsenoside-Rh2

Ginsenoside-Rh2 (G-Rh2), an intestinal bacterial metabolite of ginsenoside, has been reported to show anti-inflammatory activity in microglial cells and astroglial cells. In murine BV-2 microglial cells, G-Rh2 inhibits LPS/IFN-γ-induced generation of NO as well as the expression of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-1β, by regulating protein kinase A (PKA)/AP-1 signal pathways [78]. Moreover, G-Rh2 also suppresses TNF-α-induced intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) expression by suppressing the activities of both NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 signaling pathways in human astroglial cells [79]. Interestingly, G-Rh2-mediated modulation of NF-κB signaling was not observed in either murine microglial cells or human monocytic cells, suggesting that G-Rh2 may inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway in a cell-specific manner [78], [79].

The anti-inflammatory effects of G-Rh2 in allergic airway inflammation have also been investigated in a murine asthma model. G-Rh2 inhibits peribronchiolar inflammation, the recruitment of airway inflammatory cells, cytokine production, total and ovalbumin-specific IgE levels, and expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor, which are representative pathophysiological characteristics of asthma. Activation of NF-κB and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK are also suppressed by G-Rh2 in this disease animal model [80], indicating that G-Rh2 ameliorates allergic airway inflammation by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK. Taken together, G-Rh2 may be useful for the treatment of inflammatory airway diseases, such as asthma.

Unlike other ginsenosides, G-Rh2 exhibits low levels of oral bioavailability and water solubility, and therefore sulfated derivatives of G-Rh2 such as G-Rh2-B1 and G-Rh2-B2 have been synthesized. These derivatives of G-Rh2 reduce LPS-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β as well as the activities of p38 MAPK, JNK, and NF-κB, showing greater anti-inflammatory effects than that of G-Rh2 [81], [82], in turn suggesting that improving bioavailability and water solubility of ginsenosides could also improve their anti-inflammatory effects.

3.11. Ginsenoside-Rp1

Ginsenoside-Rp1 (G-Rp1) has been reported to show anti-inflammatory effects mainly through modulating the activity of NF-κB. G-Rh1 decreases the LPS-induced expression of IL-1β, COX-2, and iNOS by suppressing NF-κB activity in RAW264.7 cells [83], [84]. Interestingly, G-Rp1-mediated inhibition of NF-κB activation has been achieved by suppression of IKK-α phosphorylation, but not MAPK phosphorylation [83], [84]. These results indicate that G-Rh1 inhibits inflammatory responses specifically by inhibiting NF-κB activation.

4. Conclusion

Studies of the pharmacological roles of ginsenosides have focused mostly on their anticancer, antioxidative, and immunostimulatory activities. A number of recent studies, however, have presented evidence showing that ginsenosides could be used to prevent and treat a variety of inflammatory diseases via anti-inflammatory functions (Table 4). In particular, considering the action mechanisms of ginsenosides, they are expected to regulate inflammatory responses primarily through the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway. In LPS-stimulated macrophages and microglial cells, ginsenosides suppress the production of proinflammatory cytokinases such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, as well as inflammatory enzymes, such as iNOS and COX-2. The expression of these molecules is predominantly regulated by NF-κB signaling pathways, where IRAK, IKKα/β, and IκBα are included in inflammatory responses. According to the results of many in vitro studies, ginsenosides exert anti-inflammatory activities in a variety of in vivo animal models of inflammatory diseases, and show promising protective effects in animal models of colitis, alcohol-induced hepatitis, IR injury, and impaired memory diseases. Furthermore, the biological activities of ginsenoside metabolites, such as CK, G-Rh1, and G-Rh2, have been observed in diverse inflammation models. CK is effective for ameliorating symptoms in animal models of ear edema, colitis, and lethal shock. G-Rh1 and G-Rh1 also exerted anti-inflammatory effects in animal models of atopic dermatitis and asthma.

Table 4.

Summary of anti-inflammatory activities of ginsenosides

| Ginsenosides | Activities | Models | Mode of action | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-Rb1 | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Inhibiting TNF-α production | [30], [31] |

| LPS-treated murine peritoneal macrophages | Blocking activation of IRAL-1, IKK-β, NF-κB, and MAPKs | [32] | ||

| TNBS-induced colitis mice | Inhibiting IRAK-activated inflammatory response | [32] | ||

| Anti-osteoporosis | RANKL-treated osteoblasts differentiated from RAW264.7 cells | Blocking expression of c-Fos and NFATc1 by regulating RANKL-induced JNK, p38 MAPK, and NF-κΒ | [42] | |

| Compound K | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated murine peritoneal macrophages | Blocking expression of proinflammatory cytokines by downregulating activities of IRAK-1, MAPKs, IKK-β, and NF-κB | [32] |

| LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Inhibiting expression of iNOS and COX-2 by suppressing NF-κB | [45] | ||

| Zymosan-treated RAW264.7 cells and BMDMs | Reducing proinflammatory cytokines, MAPKs, and ROS | [43] | ||

| TPA-induced ear edema mice | Inhibiting NF-κB and COX-2 | [46] | ||

| TNBS-induced colitis mice | Inhibiting NF-κB | [32] | ||

| DSS-induced colitis mice | Inhibiting NF-κB | [47] | ||

| Endotoxin-induced lethal shock mice | Decreasing expression of proinflammatory cytokines | [43], [48] | ||

| Anti-inflammation and neuroprotective effect | LPS-treated microglial cells | Suppressing ROS generation, MAPKs, NF-κB, and AP-1 | [44] | |

| G-Rb2 | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated RAW264.7 and U937 cells | Inhibiting TNF-α production | [31] |

| Neuroprotective effect | LPS-treated N9 microglial cells | Suppressing TNF-α production via NF-κB inhibition | [49] | |

| G-Rd | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Reducing production of NO and PGE2, and NF-κB activity. | [51] |

| Neuroprotective effect | LPS-treated N9 cells | Suppressing TNF-α and NF-κB | [49] | |

| Transient focal cerebral ischemia rats | Inhibiting expression of iNOS and COX-2 | [50] | ||

| G-Re | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated peritoneal macrophages | Blocking IKK-β phosphorylation, NF-κB activation, and production of proinflammatory cytokines | [52] |

| TNBS-induced colitis mice | Inhibiting NF-κB, IL-1β, and TNF-α | [52] | ||

| Anti-neuroinflammation | LPS-treated BV2-microglial cells | Suppressing iNOS, COX-2, and p38 MAPK | [55] | |

| G-Rg1 | Neuroprotective effect | LPS-treated BV-2 microglial cells | Suppressing iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB via PLC-γ1 | [57] |

| LPS-injected rats | Inhibiting production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and NO via glucocorticoid receptor signaling | [58] | ||

| LPS-injected mice | Inhibiting expression of TNF-α, iNOS, and Iba-1 by blocking NF-κB and MAPKs | [56] | ||

| Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | (1) Suppressing IL-6 expression by inhibiting NF-κB (2) Increasing TNF-α expression by activation of Akt/mTOR |

[59] | |

| Alcohol-induced hepatitis mice | Inhibiting NF-κB | [60] | ||

| TNBS-induced colitis mice | Inhibiting NF-κB | [61] | ||

| Anti-ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury | Liver IR injury mice | Inhibiting NF-κB and ROS/NO/HIF | [62], [63] | |

| Cerebral IR injury rats | Activating PPAR-γ/HO-1 | [64] | ||

| Cerebral IR injury rats | Suppressing PAR-1 expression | [65] | ||

| Cerebral IR injury rats | Modulating p38 MAPK | [66] | ||

| G-Rg3 | Neuroprotective effect | Abeta42-treated BV-2 microglial cells | Inhibiting TNF-α expression and NF-κB activation | [67] |

| LPS-injected rats | Improving learning and memory impairment by inhibiting expression of proinflammatory mediators | [68] | ||

| Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs | Suppressing S-nitrosylation of NLRP3 inflammasome by reducing NO generation and iNOS expression | [69] | |

| LPS-injected mice | Reducing susceptibility to lethal endotoxin shock by regulating NO generation | [69] | ||

| G-Rg5 | Anti-lung inflammation | LPS-treated alveolar macrophages | Decreasing expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, COX-2, and iNOS by inhibiting NF-κB pathway | [70] |

| TNF-α-treated HepG2 cells | Inhibiting NF-κB, COX-2, and iNOS | [71] | ||

| LPS-injected mice | Inhibiting TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS, COX-2, and NF-κB | [70] | ||

| Anti-neuro inflammation | STZ-induced memory impaired rats | (1) Improving cognitive deficits by downregulating AChE activity and up-regulating ChAT activity (2) Increasing expression of BDNF and IGF-1 (3) Decreasing Aβ deposition (4) Suppressing COX-2 and iNOS |

[72] | |

| Scopolamine-induced memory impaired mice | Improving memory deficits by suppressing AChE activity and increasing BDNF expression and CREB phosphorylation | [73] | ||

| Anti-skin inflammation | TNF-α/IFN-γ-treated keratinocytes | Inhibiting expression of TARC/CCL17 via NF-κB/p38 MAPK/STAT signaling pathways | [74] | |

| LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Reducing generation of NO and ROS | [74] | ||

| G-Rh1 | Anti-neuro-inflammation | IFN-γ-treated BV2 microglial cells | Inhibiting iNOS expression by suppressing JAK/STAT, ERK, and NF-κB | [76] |

| Anti-skin inflammation | Oxazolone-induced atopic dermatitis-like mice | Suppressing production of IgE and IL-6, infiltration of inflammatory cells and granulation of mast cells | [77] | |

| G-Rh2 | Anti-neuroinflammation | LPS-/IFN-γ-treated BV-2 microglial cells | Reducing expression of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-1β by suppressing PKA/AP-1 | [78] |

| TNF-α-treated human astroglial cells | Inhibiting ICAM-1 expression by suppressing NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 | [79] | ||

| Anti-airway inflammation | OVA-induced asthma mice | Inhibiting peribronchiolar inflammation by suppressing NF-κB and p38 MAPK | [80] | |

| G-Rh2-B1/G-Rh2-B2 | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Reducing expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and activities of p38 MAPK, JNK, and NF-κB | [81], [82] |

| G-Rp1 | Anti-inflammation | LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Reducing expression of IL-1β, COX-2, and iNOS by suppressing NF-symbolic kappaB | [83], [84] |

Aβ, amyloid beta; AChE, acetylcholinesterase; AP-1, activator protein-1; BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor; ChAT, choline acetyltransferase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; G-RB1, ginsenoside-Rb1; G-RB2, ginsenoside-Rb2; G-Rd, ginsenoside-Rd; G-Re, ginsenoside-Re; G-Rg1, ginsenoside-Rg1; G-Rg3, ginsenoside-Rg3; G-Rg5, ginsenoside-Rg5; G-Rh1, ginsenoside-Rh1; G-Rh2, ginsenoside-Rh2; G-Rp1, ginsenoside-Rp1; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IFN, interferon; IKK, inhibitor of κB kinase; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NO, nitric oxide; OVA, ovalbumin; PKA, protein kinase A; TNBS, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfuric acid; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

In conclusion, studies of ginsenosides strongly indicate that ginsenosides and their metabolites/derivatives could serve as potent pharmaceutical agents to prevent and treat inflammatory diseases.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 2015-2016 (JYC) from the Korean Society of Ginseng, which is funded by the Korean Ginseng Corporation (KGC).

Contributor Information

Mi-Yeon Kim, Email: kimmy@ssu.ac.kr.

Jae Youl Cho, Email: jaecho@skku.edu.

References

- 1.Abbas A.K., Lichtman A.H., Pillai S. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. Basic immunology: functions and disorders of the immune system. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lodish H., Berk A., Zipursky S. 4th ed. W.H. Freeman; New York: 2000. Molecular cell biology. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janeway C.A., Travers P., Walport M., Shlomchik M.J. Garland; New York: 2001. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medzhitov R., Janeway C.A., Jr. Innate immune recognition and control of adaptive immune responses. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:351–353. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rus H., Cudrici C., Niculescu F. The role of the complement system in innate immunity. Immunol Res. 2005;33:103–112. doi: 10.1385/IR:33:2:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janeway C.A., Travers P., Walport M., Capra J.D. Garland; New York: 2005. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas A.K., Murphy K.M., Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHeyzer-Williams L., Malherbe L., McHeyzer-Williams M. Helper T cell-regulated B cell immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:59–83. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong B.N., Ji M.G., Kang T.H. The efficacy of red ginseng in type 1 and type 2 diabetes in animals. Evidence Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:593181. doi: 10.1155/2013/593181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmes S. Cancer prevention and therapeutics: Panax ginseng. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9:259–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ernst E. Complementary/alternative medicine for hypertension: a mini-review. Wiener Med Wochenschr. 2005;155:386–391. doi: 10.1007/s10354-005-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong C.S. Effect of butanol fraction of Panax ginseng head on gastric lesion and ulcer. Arch Pharm Res. 2002;25:61–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02975263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiefer D., Pantuso T. Panax ginseng. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1539–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun T.K. Brief introduction of Panax ginseng CA Meyer. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:S3. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.S.S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillis C.N. Panax ginseng pharmacology: a nitric oxide link? Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Attele A.S., Wu J.A., Yuan C.-S. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasegawa H. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic and clinical trials: metabolic activation of ginsenoside: deglycosylation by intestinal bacteria and esterification with fatty acid. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:153–157. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj04001x4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang-Xiao L., Pei-Gen X. Recent advances on ginseng research in China. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;36:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrero-Miliani L., Nielsen O., Andersen P., Girardin S. Chronic inflammation: importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in interleukin-1β generation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange C., Hemmrich G., Klostermeier U.C., López-Quintero J.A., Miller D.J., Rahn T., Weiss Y., Bosch T.C., Rosenstiel P. Defining the origins of the NOD-like receptor system at the base of animal evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:1687–1702. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proell M., Riedl S.J., Fritz J.H., Rojas A.M., Schwarzenbacher R. The Nod-like receptor (NLR) family: a tale of similarities and differences. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roach J.C., Glusman G., Rowen L., Kaur A., Purcell M.K., Smith K.D., Hood L.E., Aderem A. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9577–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinon F., Mayor A., Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coussens L.M., Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.González-Chávez A., Elizondo-Argueta S., Gutiérrez-Reyes G., León-Pedroza J.I. Pathophysiological implications between chronic inflammation and the development of diabetes and obesity. Cir Cir. 2011;79:209–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tracy R. Emerging relationships of inflammation, cardiovascular disease and chronic diseases of aging. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27 doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med. 2006;12:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhule A., Navarro S., Smith J.R., Shepherd D.M. Panax notoginseng attenuates LPS-induced pro-inflammatory mediators in RAW264.7 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;106:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho J.Y., Yoo E.S., Baik K.U., Park M.H., Han B.H. In vitro inhibitory effect of protopanaxadiol ginsenosides on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha production and its modulation by known TNF-alpha antagonists. Planta Med. 2001;67:213–218. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joh E.-H., Lee I.-A., Jung I.-H., Kim D.-H. Ginsenoside Rb1 and its metabolite compound K inhibit IRAK-1 activation—the key step of inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood A.J., Eastell R. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:736–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ginaldi L., Di Benedetto M.C., De Martinis M. Osteoporosis, inflammation and ageing. Immun Ageing. 2005;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spector T., Hall G., McCloskey E., Kanis J. Risk of vertebral fracture in women with rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1993;306:558. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6877.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gough A., Emery P., Holder R., Lilley J., Eyre S. Generalised bone loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1994;344:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernstein C.N., Blanchard J.F., Leslie W., Wajda A., Yu B.N. The incidence of fracture among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:795–799. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoon E.J., Blok B.M., Geerling B.J., Russel M.G., Stockbrügger R.W., Brummer R.J.M. Bone mineral density in patients with recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1203–1208. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bultink I.E., Lems W.F., Kostense P.J., Dijkmans B.A., Voskuyl A.E. Prevalence of and risk factors for low bone mineral density and vertebral fractures in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2044–2050. doi: 10.1002/art.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mundy G.R. Osteoporosis and inflammation. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S147–S151. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teitelbaum S.L. Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170:427–435. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng B., Li J., Du J., Lv X., Weng L., Ling C. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits osteoclastogenesis by modulating NF-κB and MAPKs pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuong T.T., Yang C.-S., Yuk J.-M., Lee H.-M., Ko S.-R., Cho B.-G., Jo E.-K. Glucocorticoid receptor agonist compound K regulates Dectin-1-dependent inflammatory signaling through inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Life Sci. 2009;85:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park J.-S., Shin J.A., Jung J.-S., Hyun J.-W., Van Le T.K., Kim D.-H., Park E.-M., Kim H.-S. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of compound K in activated microglia and its neuroprotective effect on experimental stroke in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:59–67. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park E.-K., Shin Y.-W., Lee H.-U., Kim S.-S., Lee Y.-C., Lee B.-Y., Kim D.-H. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rb1 and compound K on NO and prostaglandin E2 biosyntheses of RAW264.7 cells induced by lipopolysaccharide. Biol Pharmacol Bull. 2005;28:652–656. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee J.-Y., Shin J.-W., Chun K.-S., Park K.-K., Chung W.-Y., Bang Y.-J., Sung J.-H., Surh Y.-J. Antitumor promotional effects of a novel intestinal bacterial metabolite (IH-901) derived from the protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides in mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:359–367. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J., Zhong W., Wang W., Hu S., Yuan J., Zhang B., Hu T., Song G. Ginsenoside metabolite compound K promotes recovery of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis and inhibits inflammatory responses by suppressing NF-κB activation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang C.S., Ko S.R., Cho B.G., Shin D.M., Yuk J.M., Li S., Kim J.M., Evans R.M., Jung J.S., Song D.K. The ginsenoside metabolite compound K, a novel agonist of glucocorticoid receptor, induces tolerance to endotoxin-induced lethal shock. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:1739–1753. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu C.F., Bi X.L., Yang J.Y., Zhan J.Y., Dong Y.X., Wang J.H., Wang J.M., Zhang R., Li X. Differential effects of ginsenosides on NO and TNF-α production by LPS-activated N9 microglia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye R., Yang Q., Kong X., Han J., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Li P., Liu J., Shi M., Xiong L. Ginsenoside Rd attenuates early oxidative damage and sequential inflammatory response after transient focal ischemia in rats. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim D.H., Chung J.H., Yoon J.S., Ha Y.M., Bae S., Lee E.K., Jung K.J., Kim M.S., Kim Y.J., Kim M.K. Ginsenoside Rd inhibits the expressions of iNOS and COX-2 by suppressing NF-κB in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and mouse liver. J Ginseng Res. 2013;37:54–63. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee I.-A., Hyam S.R., Jang S.-E., Han M.J., Kim D.-H. Ginsenoside Re ameliorates inflammation by inhibiting the binding of lipopolysaccharide to TLR4 on macrophages. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9595–9602. doi: 10.1021/jf301372g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olson J.K., Miller S.D. Microglia initiate central nervous system innate and adaptive immune responses through multiple TLRs. The J Immunol. 2004;173:3916–3924. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGeer P., Itagaki S., Boyes B., McGeer E. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease brains. Neurology. 1988;38:1285–1291. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee K.-W., Jung S.Y., Choi S.-M., Yang E.J. Effects of ginsenoside Re on LPS-induced inflammatory mediators in BV2 microglial cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:196. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu J.-F., Song X.-Y., Chu S.-F., Chen J., Ji H.-J., Chen X.-Y., Yuan Y.-H., Han N., Zhang J.-T., Chen N.-H. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rg1 on lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation in mice. Brain Res. 2011;1374:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zong Y., Ai Q.-L., Zhong L.-M., Dai J.-N., Yang P., He Y., Sun J., Ling E.-A., Lu D. Ginsenoside Rg1 attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses via the phospholipase C-γ1 signaling pathway in murine BV-2 microglial cells. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:770–779. doi: 10.2174/092986712798992066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun X.-C., Ren X.-F., Chen L., Gao X.-Q., Xie J.-X., Chen W.-F. Glucocorticoid receptor is involved in the neuroprotective effect of ginsenoside Rg1 against inflammation-induced dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in substantia nigra. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;155:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y., Liu Y., Zhang X.-Y., Xu L.-H., Ouyang D.-Y., Liu K.-P., Pan H., He J., He X.-H. Ginsenoside Rg1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages through differentially modulating the NF-κB and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao Y., Chu S., Li J., Li J., Zhang Z., Xia C., Heng Y., Zhang M., Hu J., Wei G. Anti-inflammatory function of ginsenoside Rg1 on alcoholic hepatitis through glucocorticoid receptor related nuclear factor-kappa B pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;173:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee S.-Y., Jeong J.-J., Eun S.-H., Kim D.-H. Anti-inflammatory effects of ginsenoside Rg1 and its metabolites ginsenoside Rh1 and 20(S)-protopanaxatriol in mice with TNBS-induced colitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;762:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tao T., Chen F., Bo L., Xie Q., Yi W., Zou Y., Hu B., Li J., Deng X. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects mouse liver against ischemia–reperfusion injury through anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis properties. J Surg Res. 2014;191:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo Y., Yang T., Lu J., Li S., Wan L., Long D., Li Q., Feng L., Li Y. Rb1 postconditioning attenuates liver warm ischemia–reperfusion injury through ROS–NO–HIF pathway. Life Sci. 2011;88:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Y., Li X., Zhang L., Liu L., Jing G., Cai H. Ginsenoside Rg1 suppressed inflammation and neuron apoptosis by activating PPARγ/HO-1 in hippocampus in rat model of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie C.-L., Li J.-H., Wang W.-W., Zheng G.-Q., Wang L.-X. Neuroprotective effect of ginsenoside-Rg1 on cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats by downregulating protease-activated receptor-1 expression. Life Sci. 2015;121:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li G., Qian W., Zhao C. Analyzing the anti-ischemia–reperfusion injury effects of ginsenoside Rb1 mediated through the inhibition of p38α MAPK. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;94:97–103. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joo S.S., Yoo Y.M., Ahn B.W., Nam S.Y., Kim Y.-B., Hwang K.W., Lee D.I. Prevention of inflammation-mediated neurotoxicity by Rg3 and its role in microglial activation. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:1392–1396. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee B., Sur B., Park J., Kim S.-H., Kwon S., Yeom M., Shim I., Lee H., Hahm D.-H. Ginsenoside rg3 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced learning and memory impairments by anti-inflammatory activity in rats. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2013;21:381–390. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon S.-J., Park J.-Y., Choi S., Lee J.-B., Jung H., Kim T.-D., Yoon S.R., Choi I., Shim S., Park Y.-J. Ginsenoside Rg3 regulates S-nitrosylation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via suppression of iNOS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:1184–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim T.W., Joh E.H., Kim B., Kim D.H. Ginsenoside Rg5 ameliorates lung inflammation in mice by inhibiting the binding of LPS to toll-like receptor-4 on macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;12:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee S.M. Anti-inflammatory effects of ginsenosides Rg5, Rz1, and Rk1: inhibition of TNF-α-induced NF-κB, COX-2, and iNOS transcriptional expression. Phytother Res. 2014;28:1893–1896. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chu S., Gu J., Feng L., Liu J., Zhang M., Jia X., Liu M., Yao D. Ginsenoside Rg5 improves cognitive dysfunction and beta-amyloid deposition in STZ-induced memory impaired rats via attenuating neuroinflammatory responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim E.-J., Jung I.-H., Van Le T.K., Jeong J.-J., Kim N.-J., Kim D.-H. Ginsenosides Rg5 and Rh3 protect scopolamine-induced memory deficits in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ahn S., Siddiqi M.H., Aceituno V.C., Simu S.Y., Zhang J., Perez Z.E.J., Kim Y.-J., Yang D.-C. Ginsenoside Rg5: Rk1 attenuates TNF-α/IFN-γ-induced production of thymus-and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC/CCL17) and LPS-induced NO production via downregulation of NF-κB/p38 MAPK/STAT1 signaling in human keratinocytes and macrophages. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11626-015-9983-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park E.-K., Choo M.-K., Han M.J., Kim D.-H. Ginsenoside Rh1 possesses antiallergic and anti-inflammatory activities. Int Allergy Immunol. 2004;133:113–120. doi: 10.1159/000076383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jung J.-S., Kim D.-H., Kim H.-S. Ginsenoside Rh1 suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression in IFN-γ-stimulated microglia via modulation of JAK/STAT and ERK signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng H., Jeong Y., Song J., Ji G.E. Oral administration of ginsenoside Rh1 inhibits the development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions induced by oxazolone in hairless mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bae E.-A., Kim E.-J., Park J.-S., Kim H.-S., Ryu J.H., Kim D.-H. Ginsenosides Rg3 and Rh2 inhibit the activation of AP-1 and protein kinase A pathway in lipopolysaccharide/interferon-gamma-stimulated BV-2 microglial cells. Planta Med. 2006;72:627–633. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-931563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choi K., Kim M., Ryu J., Choi C. Ginsenosides compound K and Rh 2 inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α-induced activation of the NF-κB and JNK pathways in human astroglial cells. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li L.C., Piao H.M., Zheng M.Y., Lin Z.H., Choi Y.H., Yan G.H. Ginsenoside Rh2 attenuates allergic airway inflammation by modulating nuclear factor-κB activation in a murine model of asthma. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:6946–6954. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bi W.-Y., Fu B.-D., Shen H.-Q., Wei Q., Zhang C., Song Z., Qin Q.-Q., Li H.-P., Lv S., Wu S.-C. Sulfated derivative of 20 (S)-ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits inflammatory cytokines through MAPKs and NF-kappa B pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages. Inflammation. 2012;35:1659–1668. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yi P.-F., Bi W.-Y., Shen H.-Q., Wei Q., Zhang L.-Y., Dong H.-B., Bai H.-L., Zhang C., Song Z., Qin Q.-Q. Inhibitory effects of sulfated 20 (S)-ginsenoside Rh2 on the release of pro-inflammatory mediators in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;712:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim B.H., Lee Y.G., Park T.Y., Kim H.B., Rhee M.H., Cho J.Y. Ginsenoside Rp1, a ginsenoside derivative, blocks lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1beta production via suppression of the NF-kappaB pathway. Planta Med. 2009;75:321–326. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1112218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shen T., Lee J.-H., Park M.-H., Lee Y.-G., Rho H.-S., Kwak Y.-S., Rhee M.-H., Park Y.-C., Cho J.-Y. Ginsenoside Rp 1, a ginsenoside derivative, blocks promoter activation of iNOS and Cox-2 genes by suppression of an IKKβ-mediated NF-κB pathway in HEK293 cells. J Ginseng Res. 2011;35:200–208. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2011.35.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]