Highlights

-

•

Older adults reported moderate to severe acute low back pain.

-

•

Irrelevant association between acute pain intensity with disability was observed.

-

•

There is interaction between age groups and marital status with disability.

Keywords: Disability, Older adults, Oldest old, Acute low back pain, Rehabilitation

Abstract

Background

The increase in the older adult and oldest old population in Brazil is growing. This phenomenon may be accompanied by an increase in musculoskeletal symptoms such as low back pain. This condition is usually associated with disability.

Objective

To verify the association between pain intensity and disability in older adults with acute low back pain and assess whether these variables differ depending on the age group and marital status.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study conducted with 532 older adults with acute low back pain episodes. Pain intensity was assessed through the Numeric Pain Scale and disability through the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument, which shows two dimensions: “frequency” and “limitation” in performing activities. The association between pain and disability was analyzed.

Results

For the interaction effect between age groups and marital status, we found that the oldest old living with a partner performed activities of the personal domain less often compared to the oldest old living alone. The oldest old group living with a partner had a lower frequency of performing activities, but did not report feeling limited. The association of pain with disability was minimal (rho < 0.20) and thus considered irrelevant.

Conclusion

Disability in older adults with acute low back pain was influenced by the interaction between age groups and marital status and is not associated with pain intensity.

Introduction

Population aging is a global phenomenon and one of the most significant social transformations due to its impact on all sectors of society. In 2015, there were 901 million people aged 60 or more, and by 2030, this number is expected to grow to 1.4 billion.1 The percentage of people aged 60 or older in Brazil in 2010 was 7.4% and it is estimated to be 22.71% by 2050.2 Along with this increasing older population, the country has had a decline in the mortality rate among older adults and subsequent increase in the oldest old population, which in the census in 2010 accounted for 14% of the older adult population and 1.5% of the total population.2

Due to the aging of the population, demands for care of older adults has become more frequent in health services. In addition, increased musculoskeletal symptoms, including low back pain (LBP), are a very common demand from this population.3 The prevalence of LBP in older Brazilian adults was estimated at 25%, meaning one in every four older Brazilian adults presents LBP.4 This is a crippling health condition because pain is associated with difficulty in performing activities of daily living (ADLs), which can cause disability and affect the overall health status of this population.5

Disability is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as impairments, limitations in activities, or restrictions on the participation of a person, representing the dynamic interaction between health conditions and contextual factors, including personal and environmental attributes.6 Disability is influenced by many factors including pain intensity, age group, and marital status. A study conducted with 675 Dutch adults and older adults with acute LBP episodes found that, in older adults over the age of 75, the higher the reported pain during the evaluation, the higher the disability was.7 Regarding marital status, the literature indicates that, even without pain symptoms, married older adults had lower disability when compared to older adults living alone.9, 10, 11

LBP is a major problem of public health worldwide8 due to its impact on disability, which in the elderly population results in greater dependency, vulnerability, and decreased quality of life.9 Given the lack of studies on the Brazilian older adult population with acute LBP, the high prevalence of this condition,4 and the effects of disability on the health of this population,10 the present study aims to determine the association between pain intensity and disability in older adults with acute LBP and to assess whether age and marital status groupings differ in these variables.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional observational study. It is part of the multicenter project named Back Complaints in the Elderly (BACE), a prospective observational epidemiological cohort study developed by an international consortium in the Netherlands, Australia, and Brazil.11, 12 This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil (ETIC 0100.0.203.000-11).

Sample

Older adults over 60 years of age of both sexes and residents in the cities of Belo Horizonte-MG and Barbacena-MG who participated in the BACE Brazil baseline. Participants who had an episode of acute LBP within six weeks of the first data collection and who did not seek health assistance for LBP in the six months preceding data collection were selected.13 LBP is defined as pain, muscle tension, or stiffness located below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds.14 It is classified as acute when there is an episode of pain lasting up to six weeks.15

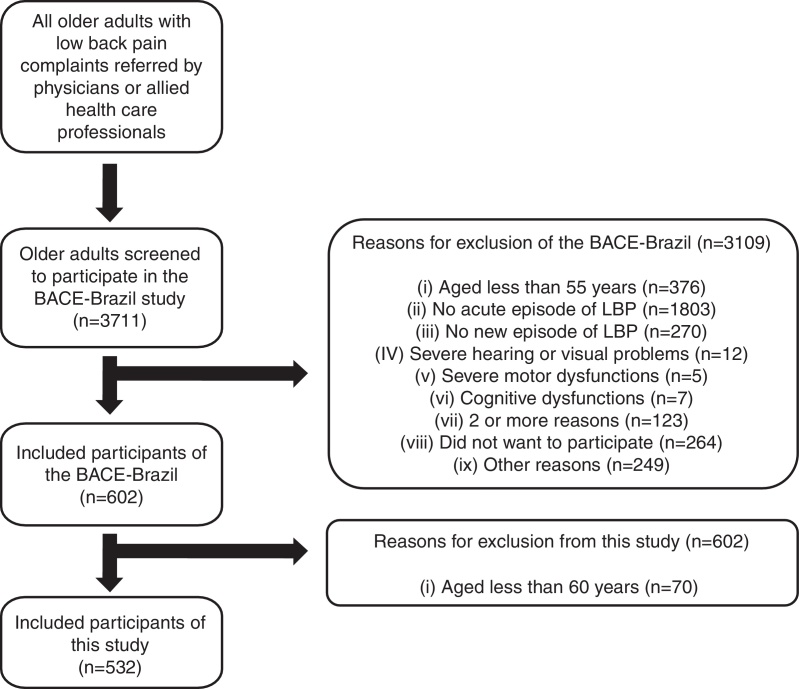

The project data were collected from the second half of 2011 and finalized in September 2014. This is a convenience sample consisting of older adults referred by health professionals working in health centers, hospitals, and clinics of both the public and private networks. An active search was also carried out by the researchers involved. The study excluded older adults with serious illnesses (infectious processes, malignant tumors, and acute disk herniation), visual, hearing, or severe motor or cognitive impairments identified from the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), according to the theoretical framework of Bertolucci et al.16 Volunteers who agreed to participate signed the informed consent form (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the participant recruitment process.

Instrumentation

The following assessment protocols were used in this study: the BACE-Brazil sociodemographic questionnaire, Numeric Pain Scale (NPS), and the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI). The BACE-Brazil sociodemographic questionnaire is composed of questions regarding: age, date of birth, gender, marital status, health service used, skin color or race, education level, income, fragility, hospitalization, and institutionalization. In this study, only the variables age and marital status were included and further stratified into two categories: age, 60–74 years (older adults) or >75 years (oldest old); marital status, living alone or living with a partner.

NPS allows quantifying pain intensity using a numeric ordinal scale. It is an 11-point scale, from zero to ten, in which zero represents “no pain” and ten is the “worst possible pain.” It can be applied verbally or through graphics, and it has been shown to be reliable when used to measure the intensity of pain in older adults.17

LLFDI was developed by Jette et al.18 in order to evaluate function and disability in older adults living in the community through interviews.18 It was translated and adapted to the Brazilian population in 2013.19 In the present study, only the ‘disability’ component of this instrument was used with its two dimensions: “frequency” and “limitation”.19 The “frequency” dimension refers to the regularity with which the individual performs ADLs in two domains: social and personal. The “limitation” dimension is the capacity perceived by the subject in performing ADLs, considering the influence of personal limiting factors (such as health, physical, or mental energy) and environmental factors (such as transportation, accessibility, and socioeconomic issues) in two domains: instrumental and management.18, 19 Scores close to 100 mean high levels in frequency of participation in activities and high levels of capability to participate in daily living tasks. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version were tested in 45 older adults with higher values of intra-examiner reliability and inter-examiner reliability compared to the original version.19

Procedure

For this study, information on sociodemographic data (age and marital status), perception of pain intensity at the time of the evaluation, and information regarding disability were drawn from the general BACE-Brazil database. These data were initially explored and submitted to descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. The BACE Brazil database was triple-checked by three researchers in order to ensure greater reliability and consistency of results.

Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The association analysis between pain and disability (LLFDI) and its domains were carried out via Spearman's correlation test. Associations lower than rho < 0.20, even if significant, were not considered because they were clinically irrelevant.20 Two-way ANOVA was performed to determine the main effects of “age group” (older adults with <75 years; oldest old with >75 years) and “marital status” (living alone; living with a partner). When there was a significant interaction between “age groups” and “marital status”, the sample was separated and compared among: older adults living alone; older adults living with a partner; oldest old living alone; and oldest old living with a partner. Bonferroni's post hoc test was used. The level of significance used was α < 0.05, and the data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range).

Results

Older adults, being predominantly female, had an average age of 69.04 (SD: 6.25) years. Other sociodemographic data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n = 532).

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 456 (85.7) |

| Male | 76 (14.3) |

| Age group | |

| 60–74 years | 410 (77.1) |

| ≥75 years | 122 (22.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Living with a partner | 239 (45.0) |

| Living alone | 293 (55.0) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 39 (7.3) |

| Elementary school (1st to 4th grade) | 202 (38.0) |

| Elementary school (5th to 8th grade) | 100 (18.8) |

| High school | 93 (17.5) |

| Technical school | 19 (3.6) |

| Higher education | 40 (7.5) |

| Postgraduate studies | 39 (7.3) |

| Income | |

| Up to 1 time the minimum wage | 221 (41.5) |

| 2 times the minimum wage | 154 (28.9) |

| 3 times the minimum wage | 59 (11.1) |

| 4 times the minimum wage | 37 (7.0) |

| 5 or more times the minimum wage | 61 (11.5) |

Acute LBP was classified as severe (median 8.0, interquartile range: 4.0). Regarding total sample disability, older adults showed moderate frequency in performing daily activities. For the limitation dimension, the results indicate a moderate perception of limitation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age, marital status, and interaction effects according to disability outcomes (n = 532).

| Variables | Total sample (n = 532) | Age |

F (p-value) Age (df = 1) |

Marital status |

F (p-value) Marital status (df = 1) |

F (p-value) Interaction (df = 1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adults (n = 410) | Oldest old (n = 122) | Living alone (n = 293) | Living with a partner (n = 239) | |||||

| Frequency | 49.23 ± 6.34 | 49.49 ± 6.22 | 48.38 ± 6.71 | 5.16 (0.024) | 49.45 ± 6.08 | 48.98 ± 6.72 | 3.83 (0.049) | 3.54 (0.060) |

| Limitation | 68.87 ± 13.12 | 68.81 ± 13.52 | 69.09 ± 14.25 | 0.29 (0.588) | 68.14 ± 13.57 | 69.78 ± 13.77 | 2.39 (0.123) | 0.47 (0.494) |

| Social | 43.45 ± 8.85 | 43.90 ± 8.77 | 41.92 ± 8.98 | 5.33 (0.021) | 43.21 ± 8.63 | 43.76 ± 9.12 | 0.04 (0.834) | 0.98 (0.323) |

| Personal | 58.22 ± 13.12 | 58.40 ± 12.95 | 57.63 ± 13.70 | 2.37 (0.124) | 59.94 ± 13.80 | 56.12 ± 11.93 | 16.68 (0.000) | 4.60 (0.032) |

| Instrumental | 68.30 ± 15.16 | 68.12 ± 15.01 | 68.91 ± 15.71 | 0.65 (0.420) | 67.53 ± 15.29 | 69.26 ± 14.97 | 2.17 (0.141) | 0.36 (0.549) |

| Management | 83.63 ± 15.76 | 84.07 ± 15.56 | 82.19 ± 16.41 | 0.55 (0.460) | 83.05 ± 15.89 | 84.37 ± 15.60 | 1.60 (0.207) | 1.03 (0.310) |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. df, degrees of freedom.

Correlation analyses showed that, although there was a significant association (p < 0.05) of LBP with the dimensions frequency, limitation, personal, instrumental, and management, the magnitude of the indices was very small (rho < 0.20) and therefore not considered relevant. There was no correlation between the LBP and the social domain (p > 0.05).

In the analysis of the differences between age groups and marital status, the oldest old group had a lower frequency of performing ADLs (p = 0.02) compared to older adults regarding disability, especially in the social domain (p = 0.02), and the living with a partner group had a lower frequency of performing ADLs (p = 0.049) compared to the living alone group, especially in the personal domain (p < 0.001). However, no difference was found in the perception of limitation to perform these activities (p > 0.05) (Table 2, Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean difference and 95% confidence interval of the difference for the comparisons between age groups, marital status, and interaction effects, according to disability outcomes (n = 532).

| Variables | Age | Marital status | Age and marital status interaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older vs oldest old | Living alone vs living with a partner | Older adults: living alone vs living with a partner | Oldest old: living alone vs living with a partner | |

| Frequency | 1.11 (0.16 to 2.40) | 0.46 (0.62 to 1.56) | −0.11 (−1.75 to 1.52) | 3.30 (−0.02 to 6.62) |

| Limitation | −0.28 (−3.06 to 2.49) | −1.64 (−3.98 to 0.70) | −1.26 (−4.80 to 2.29) | 3.46 (−10.65 to 3.72) |

| Social | 2.00 (0.21 to 3.78) | 0.55 (−2.07 to 0.97) | −1.03 (3.31 to 1.26) | 2.11 (−2.53 to 6.74) |

| Personal | 0.78 (−1.89 to 3.43) | 3.82 (1.60 to 6.05) | 2.51 (−0.83 to 5.86) | 9.70 (2.90 to 16.49) |

| Instrumental | −0.79 (−3.86 to 2.29) | −1.73 (−4.33 to 0.86) | −1.42 (−5.35 to 2.51) | −3.53 (−11.50 to 4.43) |

| Management | 1.88 (−1.31 to 5.08) | −1.32 (−4.03 to 1.38) | −0.40 (−4.48 to 3.68) | −4.26 (−12.53 to 4.02) |

Data are expressed as mean difference (lower to upper limit of the 95% confidence interval of the difference).

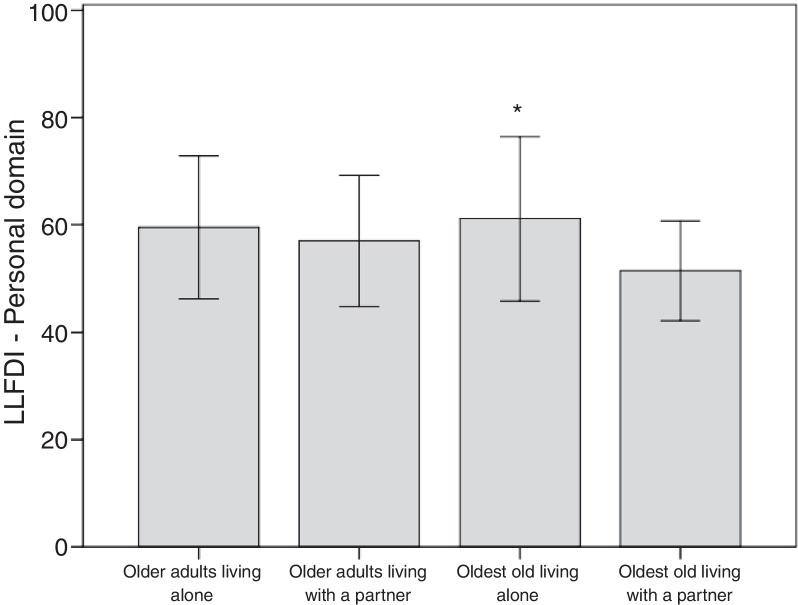

The results revealed a significant interaction effect with the oldest old living with a partner, who performed activities of the personal domain less often (p = 0.03) compared to the oldest old living alone (Fig. 2). However, no interaction was found in other areas of the LLFDI (p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effect of interaction between age and marital status in the personal domain. *p < 0.01 versus oldest old living with a partner group (Bonferroni's post hoc test). Data expressed as mean and standard deviation.

Discussion

The results showed an interaction between age groups and marital status, in which the oldest old living with a partner had a lower frequency of performing daily activities of the personal domain when compared to the oldest old living alone. This result differs from other studies, which showed that disability is lower among older adults living with companions when compared to those without a partner.10, 21, 22 Studies suggest that older adults living alone show greater disability, attributed to the psychological and financial issues that often are related to the loss of a partner.23, 24 In this study, the lowest frequency in performing activities can be explained by the possibility that oldest old living with a partner are able to share in doing them together or fail to perform the activity because they have someone to help them.

Regarding the age group, the oldest old compared to older adults had a lower frequency of performing ADLs, especially in the social domain. This result can be explained by the fact that with advancing age, there is a greater likelihood of dependence for carrying out basic activities of daily life (BADLs) and instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs), since the ability to perform them involves the integration of multiple physiological systems that decline with age.22 A study conducted with 675 Dutch adults and older adults over 55 years of age who had an episode of acute LBP found that the oldest old over the age of 75 had greater disability than younger individuals.7

As for marital status, older adults living with a partner had a lower frequency of performing ADLs compared to older adults living alone, especially in the personal domain, which differs from the results found by Schoenborn25 and Wang et al.26 They reported that living with a partner is a protector for functionality of older adults, especially for BADLs and IADLs.

However, older adults from the sample reported not feeling limited in performing daily activities. According to Beauchamp et al.,27 older adults may not notice and then not report a change in their perception of limitation in performing activities that are no longer carried out or that are executed with help, but they easily realize that they perform a more common activity in their routine with less frequency, such as preparing their own meals and taking care of their personal needs. Furthermore, regarding the perceived limitations of older adults on disability, a study of older adults with disabling diseases found that they fail to perform the most difficult tasks or do them sporadically or with help, and they reported that they did not feel limited because they stopped performing or performed these activities differently.28

Older adults reported moderate to severe pain with irrelevant correlation to disability and their domains. This result can be explained by the acute characteristic of LBP which has oscillatory behavior, with remissions and recurrences. Thus, individuals experience moments with and without pain for long periods,29 which may on the one hand hinder differentiating a pain episode and its consequences, and on the other hand, enable the performance of daily activities. Another aspect that may support the explanation of this result is resilience, which in old age translates into flexibility in the face of stressors and covers content such as: feeling competent even when accepting the help of others, being active, looking positively at life, and living connected to the present.29 According to Ramírez-Maestre and Esteve,30 resilience appears as a protector to pain, being a resource to reduce sensitivity to pain and provide better management and adaptation to painful situations. Thus, resilience may have enabled older adults in pain to develop adaptive responses to disability in this study.

This study presents limitations such as the significant proportion of women in the sample and the selection of participants in health services, which may have selected older adults who are more independent in doing daily activities. However, we emphasize the large sample size as a strong point of this study and the use of a standardized protocol with reliable and validated assessments for the Brazilian older adult population, as well as triple checking of data.

Conclusion

The results indicate that disability in older adults with acute LBP shows an interaction between age groups and marital status and is not associated with the perception of pain intensity. Knowledge of these findings may contribute to improvements in interventions by professionals in the area of rehabilitation with older adults and contribute to the creation of public policies for active aging. Thus, there is a need for studies that investigate the multidimensional aspect of disability in older adults and more specifically in the growing contingent of the oldest old.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.United Nations . Department of Economic and Social Affairs; New York: 2015. World Population Ageing 2015: Highlights. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estatística IBGE . 2012. Diretoria de Pesquisas. Coordenação de População e Indicadores Sociais. Gerência de Estudos e Análises da Dinâmica Demográfica. Evolução Demográfica 1950–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balague F., Mannion A.F., Pellise F., Cedraschi C. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):482–491. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60610-7. [Epub 2011 Oct 6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leopoldino A.A.O., Diz J.B.M., Martins V.T. Prevalence of low back pain in older Brazilians: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2016;56:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.rbre.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner D.K., Haggerty C.L., Kritchevsky S.B. How does low back pain impact physical function in independent, well-functioning older adults? Evidence from the Health ABC cohort and implications for the future. Pain Med. 2003;4(4):311–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2003.03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheele J., Enthoven W.T., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M. Characteristics of older patients with back pain in general practice: BACE cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(2):279–287. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00363.x. [Epub 2013 Jul 19] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fejer R., Leboeuf-Yde C. Does back and neck pain become more common as you get older? A systematic literature review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2012;20(1):24. doi: 10.1186/2045-709X-20-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alves L.C., Leimann B.C.Q., Vasconcelos M.E.L. A influência das doenças crônicas na capacidade funcional dos idosos do Município de São Paulo, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007;23:1924–1930. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000800019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millán-Calenti J.C., Tubío J., Pita-Fernández S. Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(3):306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teixeira L.F., Pereira L.S.M., Silva S.L.A., Dias J.M.D., Dias R.C. Factors associated with attitudes and beliefs of elders with acute low back pain: data from the study Back Complaints in the Elders (BACE) Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(6):553–560. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosa N.M.B., Queiroz B.Z., Lopes R.A., Sampaio N.R., Pereira D.S., Pereira L.S.M. Risk of falls in Brazilian elders with and without low back pain assessed using the Physiological Profile Assessment: BACE study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(6):502–509. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheele J., Luijsterburg P.A., Ferreira M.L. Back complaints in the elders (BACE); design of cohort studies in primary care: an international consortium. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Airaksinen O., Brox J.I., Cedraschi C. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(suppl 2):S192–S300. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1072-1. [Chapter 4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suri P., Rainville J., Fitzmaurice G.M. Acute low back pain is marked by variability: an internet-based pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertolucci P.H.F., Brucki S.M.D., Campacci S.R., Juliano Y. The Mini-Mental State Examination in an outpatient population: influence of literacy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1994;52:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrade F.A., Pereira L.V., Sousa F.A.E.F. Pain measurement in the elderly: a review. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2006;14:271–276. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692006000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jette A.M., Haley S.M., Coster W.J. Late life function and disability instrument: I. Development and evaluation of the disability component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(4):M209–M216. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.m209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardoso A.P., Mancini M.C., Guerra F.P., Pereira L.S.M., Assis M.G. Reliability of the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI) Brazilian Portuguese version in a sample of senior citizens with high educational level. Cad Ter Ocup UFSCar. 2015;23:237–250. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portney L.G., Watkins M.P. Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira G.N., Bastos G.A.N., Del Duca G.F., Bós A.J.G. Socioeconomic and demographic indicators associated with functional disability in the elderly. Cad Saúde Pública. 2012;28:2035–2042. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2012001100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbosa B.R., Almeida J.M., Barbosa M.R., Rossi-Barbosa L.A.R. Evaluation of the functional capacity of the elderly and factors associated with disability. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2014;19:3317–3325. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014198.06322013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudré M.R.S., Reiners A.A.O., Nakagawa J.T.T., Azevedo R.C. de S., Floriano L.A., Morita L.H.M. Prevalence of dependency and associated risk factors in the elderly. Acta Paul Enferm. 2012;25:947–953. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maciel Á.C.C., Guerra R.O. Functional limitation and survival of community dwelling elderly. Rev Assoc Méd Bras. 2008;54:347–352. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302008000400021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenborn C.A. Marital status and health: United States, 1999–2002. Adv Data. 2004;(351):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D., Zheng J., Kurosawa M., Inaba Y., Kato N. Changes in activities of daily living (ADL) among elderly Chinese by marital status, living arrangement, and availability of healthcare over a 3-year period. Environ Health Prev Med. 2009;14(2):128–141. doi: 10.1007/s12199-008-0072-7. [Epub 2009 Jan 20] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beauchamp M.K., Schmidt C.T., Pedersen M.M., Bean J.F., Jette A.M. Psychometric properties of the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira J.K., Firmo J.O.A., Giacomin K.C. Ways of thinking and acting of the elderly when tackling functionality/disability issues. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:3375–3384. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014198.11942013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontes A.P., Neri A.L. Resilience in aging: literature review. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20:1475–1495. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015205.00502014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramírez-Maestre C., Esteve R. The role of sex/gender in the experience of pain: resilience, fear, and acceptance as central variables in the adjustment of men and women with chronic pain. J Pain. 2014;15(6):608–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.006. e601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]