Abstract

Classical learning theories predict extinction after the discontinuation of reinforcement through prediction errors. However, placebo hypoalgesia, although mediated by associative learning, has been shown to be resistant to extinction. We tested the hypothesis that this is mediated by the suppression of prediction error processing through the prefrontal cortex (PFC). We compared pain modulation through treatment cues (placebo hypoalgesia, treatment context) with pain modulation through stimulus intensity cues (stimulus context) during functional magnetic resonance imaging in 48 male and female healthy volunteers. During acquisition, our data show that expectations are correctly learned and that this is associated with prediction error signals in the ventral striatum (VS) in both contexts. However, in the nonreinforced test phase, pain modulation and expectations of pain relief persisted to a larger degree in the treatment context, indicating that the expectations were not correctly updated in the treatment context. Consistently, we observed significantly stronger neural prediction error signals in the VS in the stimulus context compared with the treatment context. A connectivity analysis revealed negative coupling between the anterior PFC and the VS in the treatment context, suggesting that the PFC can suppress the expression of prediction errors in the VS. Consistent with this, a participant's conceptual views and beliefs about treatments influenced the pain modulation only in the treatment context. Our results indicate that in placebo hypoalgesia contextual treatment information engages prefrontal conceptual processes, which can suppress prediction error processing in the VS and lead to reduced updating of treatment expectancies, resulting in less extinction of placebo hypoalgesia.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT In aversive and appetitive reinforcement learning, learned effects show extinction when reinforcement is discontinued. This is thought to be mediated by prediction errors (i.e., the difference between expectations and outcome). Although reinforcement learning has been central in explaining placebo hypoalgesia, placebo hypoalgesic effects show little extinction and persist after the discontinuation of reinforcement. Our results support the idea that conceptual treatment beliefs bias the neural processing of expectations in a treatment context compared with a more stimulus-driven processing of expectations with stimulus intensity cues. We provide evidence that this is associated with the suppression of prediction error processing in the ventral striatum by the prefrontal cortex. This provides a neural basis for persisting effects in reinforcement learning and placebo hypoalgesia.

Keywords: classical conditioning, extinction learning, functional connectivity, placebo analgesia, prediction error, ventral striatum

Introduction

Placebo hypoalgesia refers to beneficial responses to the contextual factors surrounding analgesic treatments that influence pain perception, even if the treatment has no pharmacological effect (Büchel et al., 2014; Wager and Atlas, 2015). The experience of pain relief through classical conditioning is an important mechanism for the development of placebo hypoalgesia (Colloca and Miller, 2011). During conditioning, volunteers' expectations of pain relief are reinforced (acquisition phase: pain is reduced in the placebo condition). In a subsequent test phase, the reinforcement is discontinued (extinction phase: pain is identical for placebo and control). Importantly, formal learning theories (Rescorla and Wagner, 1972) predict placebo hypoalgesia to extinguish after a few trials in the test phase, which is analogous to extinction in aversive and appetitive conditioning (Quirk and Mueller, 2008; Delamater and Westbrook, 2014). However, placebo hypoalgesia has been shown to persist or even increase in the test phase, even when reinforcement is discontinued (Montgomery and Kirsch, 1997; Colloca and Benedetti, 2006).

Learning theories suggest that the updating of expectations during extinction is driven by the difference of expectation and subsequent outcome [i.e., the prediction error (PE); Rescorla and Wagner, 1972]. At the neural level, the ventral striatum (VS) is crucially involved in prediction error processing (O'Doherty et al., 2003; Garrison et al., 2013). Consequently, this suggests that decreased prediction error processing in the VS during the test phase could be the basis for the reduced extinction observed in placebo hypoalgesia. In line with this notion, neural correlates of prediction errors have not been observed in placebo hypoalgesia, but have been observed in other pain modulation paradigms (Seymour et al., 2004, 2007).

Placebo hypoalgesia is not only a conditioned response, but is also influenced by conceptual beliefs about treatments, referring to knowledge, assumptions, and beliefs about how treatments are working (Moerman and Jonas, 2002). These beliefs can provide a model of the treatment environment and influence perceptions, expectations, and behaviors (Gläscher et al., 2010; Etkin et al., 2015). The processing of conceptual information is strongly associated with the prefrontal cortex (PFC; Miller and Cohen, 2001; Koechlin and Summerfield, 2007). Consistent with this, contextual knowledge about a learning task can influence volunteers' expectations in appetitive and aversive learning (Li et al., 2011; Atlas et al., 2016). On the neural level, this was mediated by reduced prediction error processing in the VS and negative functional coupling between the VS and the PFC, indicating that the PFC can influence the processing of prediction errors in the VS. The prefrontal cortex is also a central part of the network of brain regions mediating placebo hypoalgesia (Wager et al., 2004; Lui et al., 2010). Therefore, we tested whether the prefrontal cortex can make placebo hypoalgesic effects more persistent through a downregulation of prediction error processing in the VS.

To test this hypothesis, we compared pain modulation in a treatment context (placebo hypoalgesia) with pain modulation in a stimulus reduction context (Ploghaus et al., 2001; Atlas et al., 2010) in combination with BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). During conditioning, volunteers learned to expect low or high pain after two visual cues followed by a subsequent test phase without reinforcement. Volunteers in the treatment context were told that a treatment caused the lower pain while in the stimulus context they were told that it was caused by a reduction of the pain stimulus intensity (Fig. 1A). In contrast to placebo hypoalgesia, pain modulation in the stimulus reduction context is not influenced by conceptual beliefs about treatments. This allowed us to compare two well established pain modulation models to investigate the specific influence of the treatment context. In each trial, volunteers rated expected and actual experienced pain (Fig. 1B). Comparing both ratings allowed us to compute individual prediction errors for each trial and to correlate those with prediction error signals in the VS. Additionally, the categorical comparison of both context groups allowed us to investigate the influence of conceptual beliefs about treatments on prediction error processing.

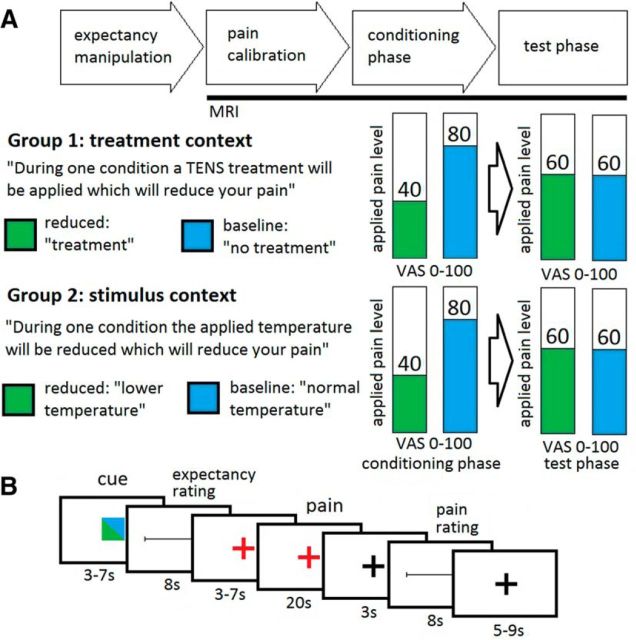

Figure 1.

Experimental design. A, Volunteers received heat pain stimuli on their forearm during two fMRI sessions. The treatment context group was told that during one condition they would receive a treatment that would reduce their pain (reduced, green) while the other condition would be untreated (baseline, blue). The stimulus context group was told that during one condition they would receive temperature-reduced pain stimuli (reduced, green) while during the other condition they would receive normal pain stimuli (baseline, blue). Both groups performed a conditioning phase and a test phase. During each session, nine reduced and nine baseline trials were presented. B, During each trial, a cue was presented to indicate the reduced or the baseline condition, followed by a rating of their expected pain (expectancy rating). After the heat pain stimulation, volunteers had to rate their experienced pain (pain rating).

Materials and Methods

Volunteers

Forty-eight healthy volunteers were included in the analysis (24 in the treatment context [mean (±SD) age, 25.6 ± 3.1 years; age range, 20–33 years; 13 males, 11 females] and 24 in the stimulus context [mean (±SD) age, 25.2 ± 3.2 years; age range, 20–32 years; 12 males, 12 females)]. Four volunteers were excluded beforehand due to misapprehension of the instructions (1), technical difficulties (2), or anxiety in the scanner (1). Volunteers were recruited using an internet advertisement platform frequently visited by students of the University of Hamburg. Exclusion criteria were neurological diseases (including pain syndromes), skin affections on the forearms, current medication (excluding oral contraceptives), substance abuse, and pregnancy. None of the volunteers reported relevant depressive symptoms [ADS-K (Allgemeine Depressionsskala, short form) score, >23]. All volunteers gave written consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Council of Hamburg.

Experimental design

The study was designed to investigate prediction error processing during a conditioning phase and a test phase in a treatment context and a stimulus context. The design was exactly the same in both context groups with the exception of the instruction to the volunteers (Fig. 1A). After the consent process, volunteers were guided to an examination room where they read instructions about the experimental task. Then, volunteers were visited by the experimenter, who was wearing a white coat and who verbally repeated the instructions in a standardized manner. The instructions included the information that during their time in the scanner they will receive painful thermal stimuli, which are visually cued by one of two colors (green or blue). Volunteers in the treatment context were told that while pain stimuli cued by one color are present, they will receive analgesic treatment by a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (and therefore they will feel less pain; Colloca and Benedetti, 2006), while during the stimuli cued by the other color no treatment will be given. Volunteers in the stimulus context were told that stimuli cued by one color will be of a lower temperature (and therefore they will feel less pain), while the stimuli cued by the other color will be at standard temperature. We refer to the placebo treatment/low temperature status as the “reduced condition” and the no treatment/normal temperature status as the “baseline condition.” To strengthen the believability in our sham analgesic electrical stimulation, an intensity calibration of the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation was performed. Two electrodes were placed on the left volar forearm, and a current eliciting a just perceivable pricking sensation was applied several times. Importantly, this procedure was only used before the main experimental phase, during the experiment no electrical stimulation was applied. Then, to test whether our manipulation was successful, volunteers completed a short questionnaire regarding their expected pain in both conditions.

After a short delay, volunteers were placed in the MR scanner and a temperature calibration was performed. Volunteers were lying in the scanner but no imaging measurements were performed, allowing the volunteers to adapt to the scanner environment and pain stimuli. Heat pain stimuli were applied using a Thermode (TSAII, Medoc). The heat pain threshold was assessed using the method of limits (Fruhstorfer et al., 1976) with a slope of 0.3°C/s. Five additional blocks of two pain stimuli each (10 s duration) were used to approximate an individual stimulation temperature corresponding to 60 on a visual analog scale (VAS; 0–100) for each volunteer. Corresponding temperatures of 0.6°C lower and higher were used during the conditioning phase. After the temperature calibration, the fMRI data acquisition started. The fMRI measurements consisted of two sessions, one corresponding to the conditioning phase and one to the test phase. Each session consisted of 18 trials. During the conditioning phase, volunteers received nine stimuli corresponding to an average VAS score of 40 during the reduced condition and nine stimuli corresponding an average VAS score of 80 during the baseline condition. Of each set of these nine stimuli, two had a slightly lower temperature and two a slightly higher temperature (±0.2°C) in a pseudorandomized order. Each trial started with a visual cue with a duration of 3–7 s (Fig. 1B). The cue consisted of a green or blue square in the middle of the screen, indicating to the volunteer whether they should expect a reduced or a baseline trial. The colors were counterbalanced between volunteers. After the visual cue, volunteers had to rate the expected pain during the subsequent pain stimulation on a VAS (0–100; end points labeled with “no pain at all” and “unbearable pain,” 8 s). A red fixation cross indicated that the pain stimulation would follow soon (3–7 s). The pain stimulation lasted for 20 s (1.5 s ramp up, 17 s plateau, 1.5 s ramp down). After a delay of 3 s, volunteers rated their perceived pain intensity on a VAS (0–100; end points labeled with “no pain at all” and “unbearable pain,” 8 s). This was followed by a variable intertrial interval (5–9 s). Directly after the conditioning phase, the test phase started. The trial design was identical to the conditioning phase; however, the stimuli in both conditions corresponded to an average VAS score of 60. The test phase was followed by an 8 min T1 scan. Afterward, volunteers left the scanner and filled out the “belief about medicines” questionnaire (Horne et al., 1999) and other questionnaires concerning emotional state and personality variables. The experiment was concluded with a debriefing in which volunteers were informed about the nature of deception. To re-establish their autonomy, we asked for permission to use the collected data, given the use of deception. None of the volunteers withheld their approval.

Data acquisition

The control of the experimental timing and the stimulus presentation was performed using Cogent 2000 version 1.25 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London, London, UK). Volunteers operated a standard button box to provide responses. Behavioral data were collected using Matlab (MathWorks). fMRI data were acquired on a 3 tesla system (Magnetom TIM Trio, Siemens) equipped with a 32-channel head coil. To measure BOLD responses, a T2*-weighted standard gradient echoplanar imaging sequence was used [repetition time, 2.58 s; echo time, 26 ms; flip angle, 80°; field of view, 220 × 220 mm2; GRAPPA (generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions) PAT (parallel acquisition techniques) factor: 2]. Each volume consisted of 42 transversal slices with a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 and a 1 mm gap. Volumes were individually tilted by ∼30° relative to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line. The first four volumes of each session were discarded to account for T1 saturation effects. High-resolution anatomical T1-weighted scans were acquired using an MPRAGE sequence with a voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3.

Statistical analysis

Behavioral data analysis.

Behavioral data analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM). Differences in expectancy between the conditions before the fMRI sessions were investigated using paired t tests. Pain and expectancy ratings during the fMRI sessions were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models. We used condition (reduced vs baseline) as the discrete predictor, temperature deviation from the mean applied temperature as a continuous covariate, and pain ratings or expectancy ratings as dependent variables. To test for an interaction between groups, context (treatment context vs stimulus context) was added as a second discrete predictor. To test whether the prediction errors were larger in the treatment context during the test phase, the prediction error (difference between expectancy and pain rating) was used as a dependent variable. The prediction errors in the baseline condition were reversed to match the direction of learning in the reduced condition. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated between the beliefs about medicines questionnaire (BMQ) and the mean difference of the pain ratings between the reduced and the baseline condition in both groups. The BMQ assesses the cognitive representations of medications with a higher score, meaning more negative views and beliefs about treatments (Horne et al., 1999). Statistical comparison of correlations was performed using Fisher's z-test. All effects were considered significant at p < 0.05 (one or two tailed, depending on the a priori hypothesis).

fMRI data analysis.

fMRI data preprocessing and statistical analyses were performed using SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London). Data preprocessing consisted of slice timing, motion correction (realignment and unwarp), and coregistration of the T1-weighted anatomical scan with the functional images. Afterward, we performed a first-level analysis using a general linear model, as implemented in SPM12. A high-pass filter with a cutoff period of 128 s was used, and a correction for temporal autocorrelations was performed using a first-order autoregressive model. After model estimation, the contrast images were spatially normalized using DARTEL of the T1-weighted anatomical scan (based on the VBM8 template; http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/) and smoothed using a 6 mm (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel. To investigate the prediction error signals in the VS, we used a cue (3–7 s), expectancy rating (8 s), pain anticipation (3–7 s), early pain stimulation (first 10 s), late pain stimulation (second 10 s), and a pain intensity rating (8 s) regressor for each condition, modeled by boxcar functions convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function. Additionally, we calculated individual prediction errors by subtracting the expectancy rating from the pain rating for each trial (signed prediction error; Rescorla and Wagner, 1972) and used the resulting vectors as parametric modulators for early and late pain, resulting in 30 regressors for each first-level analysis. T-contrasts of interest were then calculated for the parametric modulators. To test whether a source of the prediction error-related activity modulation observed in the VS could be caused by an altered functional connectivity between the VS and the PFC, we performed a psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis (Friston et al., 1997). We used the location of the peak of the prediction error difference from the contrast between the groups as seed voxels and extracted the time series within a sphere of 4 mm diameter. The peak of the prediction error contrast was chosen because we assumed that the location where the PE difference between the contexts show the largest effect is the best candidate region to exhibit functional connectivity to the PFC. We used individual prediction errors as a psychological predictor to model prediction error-related changes in connectivity. Finally, we calculated the PPI interaction term as the time series multiplied by the psychological predictor. All three regressors were subsequently included in a new first-level analysis. After model estimation, t-contrasts of interest were calculated for the PPI interaction regressor. The resulting t-contrast images were then used for a second-level group analysis. For the second-level analysis, we used a flexible factorial design. For the prediction error analyses in the VS, we used a small-volume approach in an a priori region of interest (ROI) based on peak coordinates from a previous meta-analysis on placebo (Atlas and Wager, 2014). The ROIs were spheres with a 5 mm radius, and mean coordinates across multiple peaks were computed where available. Based on previous findings and our hypothesis, we focused our PPI analysis on the lateral PFC (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Koechlin and Summerfield, 2007; Watson et al., 2009; Lui et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011). The ROI was based on the frontal lobe mask from the WFU PickAtlas (http://fmri.wfubmc.edu/software/pickatlas). The medial and orbital PFC were anatomically defined and removed with MATLAB, and the overlap between the mask and the mean gray matter mask of the volunteers was computed. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons within an ROI as well as for the number of ROIs (left and right) using a familywise error (FWE) rate. For illustration purposes, statistical maps were thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected with a voxel extent of a minimum of 10 voxels and overlaid on the mean structural image of all volunteers. All activations are reported using x, y, z coordinates in MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) standard space.

Results

Behavioral results

Before the fMRI sessions, volunteers expected less pain in the reduced condition compared with the baseline condition in the treatment context (VAS score, 32.8 vs 52.0; t(23) = 3.6; p < 0.005) and in the stimulus context (VAS score, 26.4 vs 62.1; t(23) = 9.2; p < 0.001), indicating that our expectancy manipulation was successful. The average calibrated temperature corresponding to a VAS score of 60 was 46.0 ± 0.51°C in the treatment context and 46.0 ± 0.56°C in the stimulus context, with no observable difference between the groups (t(46) = 0.1, p = 0.9).

Volunteers had to provide an expectancy rating regarding their expected pain and a pain rating regarding their experienced pain. During the conditioning phase, the expectancy and pain ratings were lower in the reduced condition compared with the baseline condition in the treatment context (expectancy VAS score: 31.2 vs 74.0; F(1,406) = 636.5; p < 0.001; pain VAS score: 30.2 vs 82.2; F(1,406) = 1634.7; p < 0.001) and the stimulus context (expectancy VAS score: 31.7 vs 75.5; F(1,406) = 705.7; p < 0.001; pain VAS score: 29.9 vs 81.5; F(1,406) = 1741.3; p < 0.001). Both groups showed similar expectancy and pain rating differences (expectancy ΔVAS score: 42.8 vs 43.8, F(1,813) = 0.2; p = 0.7; pain ΔVAS score: 52.0 vs 51.6; F(1,813) = 0.5; p = 0.8). These results indicate that conditioning successfully led to reduced expected and experienced pain in the reduced condition and that both groups did not differ significantly in their ratings during the conditioning phase.

Next, we investigated the test phase. Expectancy and pain ratings were different between the reduced and baseline conditions in the treatment context (expectancy VAS score: 43.8 vs 73.6; F(1,406) = 498.8; p < 0.001; pain VAS score: 54.4 vs 67.7; F(1,406) = 135.1; p < 0.001) and in the stimulus context (expectancy VAS score: 51.0 vs 67.0; F(1,406) = 71.5; p < 0.001 pain VAS score: 58.6 vs 67.4; F(1,406) = 48.4; p < 0.001). The expectancy and pain rating differences in the treatment context were stronger than in the stimulus context. (expectancy ΔVAS score: 29.8 vs 16.0; F(1,813) = 36.3; p < 0.001; pain ΔVAS score: 13.3 vs 8.8; F(1,813) = 7.0; p < 0.01; Fig. 2A).

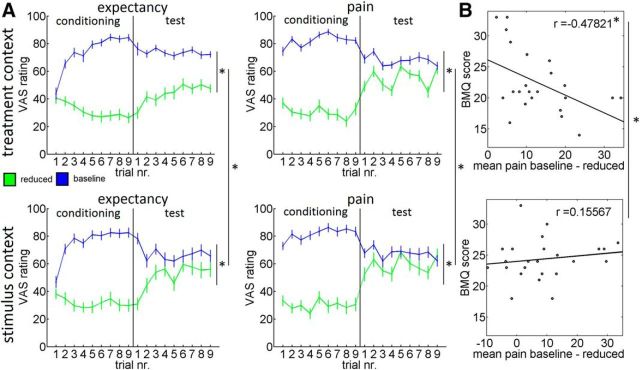

Figure 2.

Behavioral results. A, Expectancy and pain ratings (±SEM) for the treatment context and the stimulus context. During the test phase, we observed significant expectancy and pain, and rating differences between the reduced condition (green) and the baseline condition (blue) for the treatment context and the stimulus context. Both effects were significantly stronger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context. B, We observed a negative correlation between negative views and beliefs about treatments (BMQ score) and the placebo effect in the treatment context. The correlation was larger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context. *p < 0.05.

To investigate prediction error-related differences in extinction learning during the test phase, we calculated the difference between the expectancy and the pain ratings and compared these prediction errors between the contexts. The prediction errors were larger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context (F(1,46) = 3.8, p < 0.05). The results of the test phase indicate that in both groups our manipulations successfully induced pain modulation. The results also show that in the treatment context expected and experienced pain rating differences as well as prediction errors were larger, demonstrating that the treatment context group showed less extinction during the test phase compared with the stimulus context group.

Finally, we investigated whether placebo hypoalgesia is related to conceptual beliefs about treatments (Horne et al., 1999). We observed a negative correlation between negative views and beliefs about medical treatments and the placebo effect in the treatment context (r = −0.48, p < 0.05) but no significant correlation with the pain modulation effect in the stimulus context (r = 0.16, p = 0.5). The correlation was significantly stronger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context (z = −2.2, p < 0.05; Fig. 2B). This indicates that conceptual beliefs about treatments indeed influence pain perception in a treatment context.

Imaging results

Painful thermal stimulation

During painful thermal stimulation (all sessions, pain vs fMRI baseline), volunteers showed BOLD response increases in brain regions previously associated with pain processing (Duerden and Albanese, 2013). We observed BOLD response increases in the bilateral posterior insula (right: F(1,138) = 516.63; pFWE < 0.001; MNI coordinates [38, −17, 18]); left: F(1,138) = 151.62; pFWE < 0.001; [−36, −18, 12]), bilateral anterior insula (right: F(1,138) = 431.31; pFWE < 0.001; [33, 26, 3]; left: F(1,138) = 149.27; pFWE < 0.001; [−30, 23, 8]), bilateral secondary somatosensory cortex (right: F(1,138) = 402.70; pFWE < 0.001; [56, −23, 26]; left: F(1,138) = 240.44; pFWE < 0.001; [−56, −27, 20]), bilateral thalamus (right: F(1,138) = 238.72; pFWE < 0.001; [−12, −32, 0]; left: F(1,138) = 160.02; pFWE < 0.001; [14, −32, 0]), bilateral primary somatosensory cortex (right: F(1,138) = 232.71; pFWE < 0.001; [48, −18, 54]; left: F(1,138) = 164.07; pFWE < 0.001; [−51, −25, 45]), and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (right: F(1,138) = 108.27; pFWE < 0.001; [8, 14, 53]).

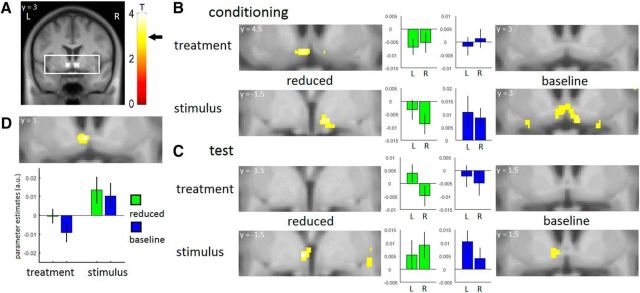

Prediction errors mediate acquisition learning in both contexts

We obtained expectation and pain ratings for each trial, allowing us to calculate prediction errors for each trial (Rescorla and Wagner, 1972) and to investigate BOLD signal correlates of these prediction error signals. Based on previous findings (O'Doherty et al., 2003; Seymour et al., 2007; Delgado et al., 2008b; Garrison et al., 2013), we focused our analysis on the VS. We used coordinates from a previous meta-analysis on pain modulation and placebo hypoalgesia to create an ROI for the right and left VS (Atlas and Wager, 2014). As prediction errors represent a mismatch between expectancy and outcome, pain has to be experienced before prediction error signals can be observed. Additionally, previous research suggests that the placebo-induced cognitive evaluation of pain happens primarily during late pain (Wager et al., 2004; Price et al., 2007). Therefore, we chose to investigate the early and late pain periods separately, similar to previous research (Wager et al., 2004; Price et al., 2007; Eippert et al., 2009) and expected to observe prediction errors during the late pain period. In the late pain period during the conditioning phase, we observed a negative prediction error signal in the left VS in the reduced condition in the treatment context (t(46) = 3.44; p < 0.05 [−4.5, 4.5, −10.5]), in the right VS in the reduced condition in the stimulus context (t(46) = 3.24; p < 0.05 [7.5, −1.5, −9]), and a positive prediction error signal in the left and right VS in the baseline condition in the stimulus context (left VS: t(46) = 3.08; p < 0.05 [−4.5, 1.5, −10.5]; right VS: t(46) = 3.06; p < 0.05 [7.5, 3, −10.5]; Figure 3A,B). We did not observe a significant prediction error signal in the baseline condition in the treatment context. In the early pain period, we observed a negative prediction error signal in the right VS in the reduced condition in the stimulus context (t(46) = 3.26; p < 0.05; [9, 7.5, −7.5]).

Figure 3.

Neural prediction error signals. A, ROIs within field of view and T-bar. Arrow indicates the T value necessary for significance (T = 3.1). B, During the conditioning phase, we observed significant prediction error signals in the ventral striatum in the reduced condition in the treatment context and in the reduced and baseline conditions in the stimulus context. The figure shows significant peaks and ROI parameter estimates. C, During the test phase, we observed significant prediction error signals in the ventral striatum in the reduced and baseline conditions only in the stimulus context. The figure shows significant peaks and ROI parameter estimates. D, The prediction error signals in the ventral striatum were stronger in the stimulus context compared with the treatment context. The figure shows significant peaks and peak parameter estimates. For illustration purposes, all statistical maps were thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected with a minimum voxel extent of 10 voxels and overlaid on the mean structural image of all volunteers.

Prediction error processes are reduced during extinction learning in a treatment context

In the late pain period during the test phase, we observed a positive prediction error signal in the stimulus context in the left VS in the reduced condition (t(46) = 3.75; p < 0.05 [−3, 1.5, −6]) and in the left VS in the baseline condition (t(46) = 3.12; p < 0.05 [−4.5, 1.5, −6]; Fig. 3C). Importantly, we did not observe significant prediction error signals in the treatment context. Next, we investigated whether the VS is differentially involved between both groups. We observed a significant effect, with stronger prediction error signals in the stimulus context compared with the treatment context during the test phase (t(46) = 4.84; p < 0.05 [−3, 1.5, −6]; Fig. 3D). No significant results were observed in the early pain period.

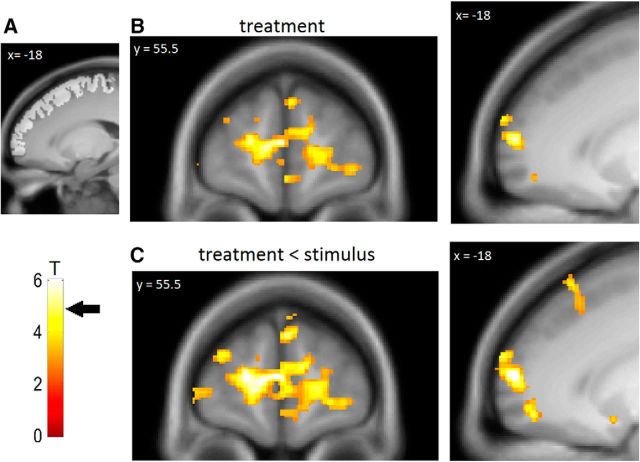

The treatment context is associated with negative functional coupling between the VS and the PFC

The PFC has previously been implicated in the processing of treatment expectancies and top-down control (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Lorenz et al., 2003). To investigate whether the observed reduction of prediction error signals in the VS in the treatment context is related to prefrontal processes, we conducted a PPI analysis between the individual time series in the VS and the individual prediction errors during the late pain period. In the treatment context, we observed a negative functional coupling between the VS and the left and right anterior PFC (left anterior PFC: t(46) = 5.67; p < 0.01 [−18, 60, 9]; right anterior PFC: t(46) = 5.58; p < 0.01 [21, 66, 7.5]; Fig. 4A,B). This negative coupling with the left and right anterior PFC was stronger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context (left anterior PFC: t(46) = 6.53; p < 0.001 [−18, 60, 9]; right anterior PFC: t(46) = 5.73; p < 0.005 [21, 66, 7.5]; Fig. 4C). In the stimulus context, no significant results were observed. This shows that only in the treatment context is there a prediction error-dependent negative coupling between the PFC and the VS.

Figure 4.

Psychophysiological interaction. A, Lateral PFC ROI and T-bar. Arrow indicates a T value necessary for significance (T = 4.9). B, We observed a negative functional coupling between the ventral striatum and the anterior PFC in the treatment context. C, The negative functional coupling was stronger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context. For illustration purposes, statistical maps were thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected with a minimum voxel extent of 10 voxels and overlaid on the mean structural image of all volunteers.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the influence of a treatment context on prediction error processing in the VS and how this influences the adjustment of expectancies and pain modulation. The expectancy and pain rating differences as well as prediction errors remained larger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context during the test phase. In the treatment context, the pain modulation was related to views and beliefs about medical treatments. On the neural level, we observed prediction error signals in both groups during the conditioning phase but only in the stimulus context during the test phase. The reduction of prediction error signals in the treatment context was associated with negative functional coupling between the VS and the anterior PFC.

As in previous studies (Colloca and Benedetti, 2006), conditioning led to reductions in expected and experienced pain. These effects were larger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context, showing that pain modulation in a treatment context is more persistent after the discontinuation of reinforcement during the test phase, even though classical conditioning theories would predict that in this case the effects would extinguish (Rescorla and Wagner, 1972). The differences between expectation and pain ratings remained larger in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context. This supports the idea that the expectations in the treatment context were not correctly updated by the mismatch between expectation and the new pain experience (i.e., the prediction error; Rescorla and Wagner, 1972).

Modulation of prediction errors in the ventral striatum

The VS has a critical role for the processing of prediction errors (Schultz et al., 1992; O'Doherty et al., 2003). Neural correlates of prediction errors in the VS have initially been associated with appetitive or reward learning (O'Doherty et al., 2003); however, there is substantial evidence that the VS also shows prediction error signals during aversive or pain learning (Seymour et al., 2004, 2005, 2007; Delgado et al., 2008b). Therefore, it has been argued that the VS has a general role in affective learning and that positive prediction errors occur when unexpected outcomes are delivered whereas negative prediction errors occur when expected outcomes are omitted (Delgado et al., 2008b).

During acquisition in the conditioning phase, we observed prediction error signals during placebo treatment in the treatment context and in both conditions in the stimulus context. Previous studies have shown that prediction errors are important for cue-based pain modulation (Seymour et al., 2004, 2005). In placebo hypoalgesia, only an increase of prefrontal activation during conditioning has been shown so far (Watson et al., 2009; Lui et al., 2010). We can show neural correlates of prediction error processes in the VS in a treatment context. The observation of this important learning signal in the VS supports that expectation–outcome differences are important for learning in both contexts and indicates that this mechanism is involved during the conditioning of pain stimulus intensity expectancies as well as treatment expectancies. In the treatment context, we did not observe a prediction error signal in the baseline condition. Expectations regarding treatment have to be updated based on the effect of the treatment (Kirsch, 1997), which is only present in the reduced (“treated”) condition, while the baseline condition cannot be used to update treatment expectations as no treatment is present. In contrast, expectations regarding pain stimulus intensity levels are likely to be updated in both conditions. This leads to increased attention to the reduced condition in the treatment context, which could bias neural processing in the VS. This is congruent with previous findings of reduced VS activity when attention is shifted away from the cue (Delgado et al., 2008a) as well as increased activation in the VS during placebo hypoalgesia compared with baseline (Atlas and Wager, 2014).

During the test phase, we observed prediction error signals in both conditions in the stimulus context but not in the treatment context. A direct comparison revealed that prediction error signals in the VS were indeed stronger in the stimulus context compared with the treatment context. While the expectancies in the stimulus context were adjusted more adequately, the mismatch between expectation and actual experience persisted and did not lead to an adequate updating of expectancies in the treatment context. Therefore, this supports the idea that prediction error signals in the VS are critical for the updating of expectancies in placebo hypoalgesia and that the absence of these signals can inhibit the updating of expectations. This is consistent with previous results showing that beliefs can modulate prediction errors and prediction error processing in the VS (Gu et al., 2015).

Top-down modulation of the VS by the PFC

The observed pattern of prediction errors provides a neural understanding of why expectations are not correctly updated within a treatment context and thus the reduced extinction of placebo hypoalgesic effects. However, it remains unclear why the processing of prediction errors is reduced within a treatment context. First, placebo effects are self-confirming response expectancies (Kirsch, 1985, 1997), as the experienced pain reduction due to the placebo confirms the treatment expectancies. Second, recent reviews suggest that conceptual and attribution processes might be an important aspect of this phenomenon (Moerman and Jonas, 2002; Wager and Atlas, 2015). For example, a patient might have the experience that a certain painkiller has proven useful to him, but on occasion an intake does not provide adequate pain relief. Based on his conceptual belief that medications should work similarly over several intakes, he might attribute the difference in perception to other factors and keep his expectation of improvement even if an intake did not prove useful. Similarly, it is likely that participants in the treatment context were influenced by their conceptual beliefs about treatments based on their individual previous experiences. This is supported by our observed correlation between treatment beliefs and the pain modulation in the treatment context. These beliefs provide a conceptual model for the participants to evaluate their pain experience and update their treatment expectancies (Etkin et al., 2015), and previous research shows that these model-based processes influence prediction error-based learning (Gläscher et al., 2010).

Converging evidence strongly indicates that the PFC is involved in conceptual processing and cognitive control (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Koechlin, 2016), which clearly plays a role in placebo hypoalgesia (Lorenz et al., 2003; Wager et al., 2004; Wager and Atlas, 2015). The PFC is densely connected to the VS (Alexander et al., 1986), and it has been shown that the PFC can modulate valuation-related processing in the VS (McClure et al., 2004; Delgado et al., 2008a; Li et al., 2011). This suggests that the PFC could be involved in the suppression of prediction error signals in the VS in the treatment context. Based on previous data showing modulation of connectivity between the VS and the PFC (Li et al., 2011; Atlas et al., 2016), we directly addressed this hypothesis using a connectivity analysis where we investigated the coupling between the PFC and the VS during different contexts. This analysis revealed a negative functional coupling between the VS and the anterior PFC in the treatment context. Importantly, this coupling was stronger (i.e., more negative) in the treatment context compared with the stimulus context. The interaction between the anterior PFC and the VS was modulated by the trial-specific prediction error, indicating that the negative relationship between the PFC and the VS was especially strong when the mismatch between the expectation and pain experience was large.

These findings indicate a mechanism by which prefrontal cognitive control regions can suppress the generation of prediction error signals in a treatment context. It is important to note that our results do not imply a complete suppression, as the prediction error signals in the treatment context could just be below our detection threshold. However, it supports the idea that the prediction errors are downregulated by the PFC. Our data are consistent with results showing that contextual information about a learning task is associated with decreased activation in the VS and negative functional coupling with the PFC, suggesting that there is a shift from expectation–outcome learning to a more conceptual processing (Li et al., 2011; Atlas et al., 2016). Our findings are also consistent with results suggesting that instructions bias the processing of expectations in the striatum and not the subsequent decision-making processes (Doll et al., 2009, 2011). Further, it is consistent with transcranial magnetic stimulation data showing that a disruption of the PFC blocks placebo hypoalgesia (Krummenacher et al., 2010). Most importantly, it is consistent with our behavioral data and the association between conceptual beliefs and the pain modulation in the treatment context.

In summary, our data provide a neural basis for the understanding of persisting effects in placebo hypoalgesia. Our data support the idea that conceptual views and beliefs about treatments provide a mental model for participants as the basis for their assessment of nociceptive stimuli. These model-based conceptual processes in the PFC suppress the processing of expectation–outcome differences (i.e., prediction error signals) in the VS. Consequently, the suppression of the prediction errors in the VS prevents the adjustment of the participant's expectations, leading to more persisting pain modulation in placebo hypoalgesia.

Footnotes

Author contributions: L.A.S. and C.B. designed research; L.A.S. and C.S. performed research; L.A.S., C.S., S.O., L.C., and C.B. analyzed data; L.A.S., C.S., S.O., L.C., and C.B. wrote the paper.

L.A.S., C.S., and C.B. were funded by European Research Council Grant ERC-2010-AdG_20100407. C.B. was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 936 project A6). L.A.S. and L.C. were funded by the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (Grant 1R01-DE-025946).

References

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL (1986) Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 9:357–381. 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas LY, Wager TD (2014) A meta-analysis of brain mechanisms of placebo analgesia: consistent findings and unanswered questions. In: Placebo: handbook of experimental pharmacology (Benedetti F, Enck P, Frisaldi E, Schedlowski M, eds), pp 37–69. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas LY, Bolger N, Lindquist MA, Wager TD (2010) Brain mediators of predictive cue effects on perceived pain. J Neurosci 30:12964–12977. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0057-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas LY, Doll BB, Li J, Daw ND, Phelps EA (2016) Instructed knowledge shapes feedback-driven aversive learning in striatum and orbitofrontal cortex, but not the amygdala. Elife 5:e15192. 10.7554/eLife.15192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel C, Geuter S, Sprenger C, Eippert F (2014) Placebo analgesia: a predictive coding perspective. Neuron 81:1223–1239. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L, Benedetti F (2006) How prior experience shapes placebo analgesia. Pain 124:126–133. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L, Miller FG (2011) How placebo responses are formed: a learning perspective. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366:1859–1869. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamater AR, Westbrook RF (2014) Psychological and neural mechanisms of experimental extinction: a selective review. Neurobiol Learn Mem 108:38–51. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Gillis MM, Phelps EA (2008a) Regulating the expectation of reward via cognitive strategies. Nat Neurosci 11:880–881. 10.1038/nn.2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Li J, Schiller D, Phelps EA (2008b) The role of the striatum in aversive learning and aversive prediction errors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363:3787–3800. 10.1098/rstb.2008.0161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll BB, Jacobs WJ, Sanfey AG, Frank MJ (2009) Instructional control of reinforcement learning: a behavioral and neurocomputational investigation. Brain Res 1299:74–94. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll BB, Hutchison KE, Frank MJ (2011) Dopaminergic genes predict individual differences in susceptibility to confirmation bias. J Neurosci 31:6188–6198. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6486-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerden EG, Albanese MC (2013) Localization of pain-related brain activation: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging data. Hum Brain Mapp 34:109–149. 10.1002/hbm.21416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eippert F, Bingel U, Schoell ED, Yacubian J, Klinger R, Lorenz J, Büchel C (2009) Activation of the opioidergic descending pain control system underlies placebo analgesia. Neuron 63:533–543. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Büchel C, Gross JJ (2015) The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:693–700. 10.1038/nrn4044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ (1997) Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage 6:218–229. 10.1006/nimg.1997.0291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhstorfer H, Lindblom U, Schmidt WC (1976) Method for quantitative estimation of thermal thresholds in patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 39:1071–1075. 10.1136/jnnp.39.11.1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison J, Erdeniz B, Done J (2013) Prediction error in reinforcement learning: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37:1297–1310. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläscher J, Daw N, Dayan P, O'Doherty JP (2010) States versus rewards: dissociable neural prediction error signals underlying model-based and model-free reinforcement learning. Neuron 66:585–595. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Lohrenz T, Salas R, Baldwin PR, Soltani A, Kirk U, Cinciripini PM, Montague PR (2015) Belief about nicotine selectively modulates value and reward prediction error signals in smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:2539–2544. 10.1073/pnas.1416639112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M (1999) The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 14:1–24. 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. (1985) Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am Psychol 40:1189–1202. 10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. (1997) Specifying nonspecifics: psychological mechanisms of placebo effects. In: The placebo effect (Harrington A, ed), pp 166–186. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E. (2016) Prefrontal executive function and adaptive behavior in complex environments. Curr Opin Neurobiol 37:1–6. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Summerfield C (2007) An information theoretical approach to prefrontal executive function. Trends Cogn Sci 11:229–235. 10.1016/j.tics.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummenacher P, Candia V, Folkers G, Schedlowski M, Schönbächler G (2010) Prefrontal cortex modulates placebo analgesia. Pain 148:368–374. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Delgado MR, Phelps EA (2011) How instructed knowledge modulates the neural systems of reward learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:55–60. 10.1073/pnas.1014938108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz J, Minoshima S, Casey KL (2003) Keeping pain out of mind: the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in pain modulation. Brain 126:1079–1091. 10.1093/brain/awg102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui F, Colloca L, Duzzi D, Anchisi D, Benedetti F, Porro CA (2010) Neural bases of conditioned placebo analgesia. Pain 151:816–824. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD (2004) Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science 306:503–507. 10.1126/science.1100907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001) An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 24:167–202. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman DE, Jonas WB (2002) Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Ann Intern Med 136:471–476. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-6-200203190-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Kirsch I (1997) Classical conditioning and the placebo effect. Pain 72:107–113. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00016-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty JP, Dayan P, Friston K, Critchley H, Dolan RJ (2003) Temporal difference models and reward-related learning in the human brain. Neuron 38:329–337. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00169-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R, Matthews PM, Rawlins JN, Tracey I (2001) Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci 21:9896–9903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, Craggs J, Verne GN, Perlstein WM, Robinson ME (2007) Placebo analgesia is accompanied by large reductions in pain-related brain activity in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Pain 127:63–72. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Mueller D (2008) Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:56–72. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR (1972) A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In: Classical conditioning II: current research and theory, Vol 2 (Black AH, Prokasy WF, eds) pp 64–99. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Apicella P, Scarnati E, Ljungberg T (1992) Neuronal activity in monkey ventral striatum related to the expectation of reward. J Neurosci 12:4595–4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, O'Doherty JP, Dayan P, Koltzenburg M, Jones AK, Dolan RJ, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS (2004) Temporal difference models describe higher-order learning in humans. Nature 429:664–667. 10.1038/nature02581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, O'Doherty JP, Koltzenburg M, Wiech K, Frackowiak R, Friston K, Dolan R (2005) Opponent appetitive-aversive neural processes underlie predictive learning of pain relief. Nat Neurosci 8:1234–1240. 10.1038/nn1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, Daw N, Dayan P, Singer T, Dolan R (2007) Differential encoding of losses and gains in the human striatum. J Neurosci 27:4826–4831. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0400-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Atlas LY (2015) The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:403–418. 10.1038/nrn3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, Davidson RJ, Kosslyn SM, Rose RM, Cohen JD (2004) Placebo-induced changes in fMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science 303:1162–1167. 10.1126/science.1093065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A, El-Deredy W, Iannetti GD, Lloyd D, Tracey I, Vogt BA, Nadeau V, Jones AK (2009) Placebo conditioning and placebo analgesia modulate a common brain network during pain anticipation and perception. Pain 145:24–30. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]