Abstract

Background

Traditional medicinal plant species documentation is very crucial in Ethiopia for biodiversity conservation, bioactive chemical extractions and indigenous knowledge retention. Having first observed the inhabitants of Gubalafto District (Northern Ethiopia), the author gathered, recorded, and documented the human traditional medicinal plant species and the associated indigenous knowledge.

Methods

The study was conducted from February 2013 to January 2015 and used descriptive field survey design. Eighty-four informants were selected from seven study kebeles (sub-districts) in the District through purposive, snowball, and random sampling techniques. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews, guided field walks, demonstrations, and focus group discussions with the help of guided questions. Data were organized and analyzed by descriptive statistics with SPSS version 20 and Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

Results

A total of 135 medicinal plant species within 120 genera and 64 families were documented. Among the species, Ocimum lamiifolium and Rhamnus prinoides scored the highest informant citations and fidelity level value, respectively. In the study area, Asteraceae with 8.1% and herbs with 50.4% plant species were the most used sources for their medicinal uses. A total of 65 ailments were identified as being treated by traditional medicinal plants, among which stomachache (abdominal health problems) was frequently reported. Solanum incanum was reported for the treatment of many of the reported diseases. The leaf, fresh parts, and crushed forms of the medicinal plants were the most preferred in remedy preparations. Oral application was the highest reported administration for 110 preparations. A majority of medicinal plant species existed in the wild without any particular conservation effort. Few informants (about 5%) had only brief notes about the traditional medicinal plants. Ninety percent of the respondents have learned indigenous medicinal plants knowledge from their family members and friends secretly. Orthodox Church schools were found the main place for 65% of healer’s indigenous knowledge origin and experiences. Elders, aged between 40 and 84 years, gave detailed descriptions about traditional medicinal plants.

Conclusions

Traditional medicinal plants and associated indigenous knowledge are the main systems to maintain human health in Gubalafto District. But minimal conservation measures were recorded in the community. Thus, in-situ and ex-situ conservation practices and sustainable utilization are required in the District.

Keywords: Healer, Indigenous knowledge, Traditional plant medicines

Background

People have long histories on the uses of traditional medicinal plants for medical purposes in the world, and nowadays, this is highly actively promoted [1–3]. Evidence from Kibebew [4] showed that traditional medicines are used by 75–90% of the rural population in the world. The report from the World Health Organization [5] revealed that traditional medicinal plants were trusted primarily by 80% of the population in Africa. Traditional medicines are more liked in developing countries due to inadequate modern health services. In Ethiopia, the use of traditional plant medicines had been practiced since the ancient time [6]. In Northern Ethiopia, the major portions (87%) of the traditional medicines are coming from plant sources [7]. However, the traditional medicines are far from the expected level of uses, safety, and efficacy in the world [8, 9]. In Ethiopia, the bulk of the medicinal plants were collected from natural vegetation, and nowadays, natural vegetation is shrinking due to environment degradation and overuses. Therefore, it is necessary to document medicinal plant species for conservation and sustainable consumption. In addition, ethnobotanical studies on traditional medicinal plants are also the means to increase the capacity of the pharmaceutical industries. However, the documented medicinal plants are still limited when they are compared with the multi-cultural diversity of the people and the diverse flora in Ethiopia [10]. In Gubalafto District, the people live in places which are grouped into peaks, highlands, middle lands, and low lands. In such diverse environments, traditional medicinal plant species and their uses are expected to be more. However, no scientific documentation on the medicinal plant resources has so far been made in Gubalafto District. If any cultural changes take place in this community and the vegetation is degraded due to various factors, the knowledge of the people on the plant resource will vanish slowly. Moreover, some of the medicinal plant species may become extinct from the District before being documented and the people may lose their uses and their indigenous knowledge on them forever. Therefore, the ethnomedicinal study on the plants of Gubalafto is crucial in order to protect the plants under ex-situ and in-situ conservation and to preserve the associated indigenous knowledge in the District and beyond. Thus, the author documented the traditional medicinal plant species and the associated indigenous knowledge used for the treatment of human ailments in Gubalafto District.

Methods

Description of the study area

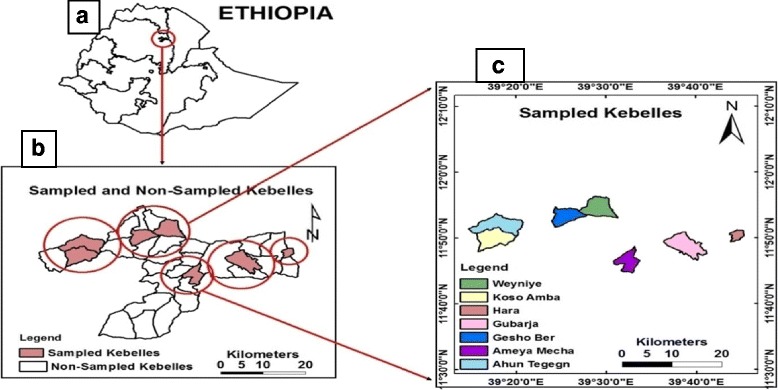

Gubalafto District is found in North Wollo Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia, by which Woldia is the main town of the District. Woldia is about 506 km far from Addis Ababa, and the main road cross it to Mekele, Dessie, Bahir Dar, and Lalibela towns. It consists of 34 kebeles, and it is situated between 39° 12′ 9″–39° 45′ 58″ East and 11° 34′ 54″–11° 58′ 59″ North (Fig. 1). The topography of the District ranges between 1100 and 3700 m above sea level (m.a.s.l) and mostly characterized by a chain of mountains (35%), undulations (30%), flats (20%), and gorges/valleys (15%). In addition, Gubalafto District is classified into four agro-ecological zones based on their altitudinal variation and climatic conditions. These are lowlands (1100–1500 m.a.s.l), middle lands (1500–2300 m.a.s.l), highlands (2300–3200), and peaks (3200–3700 m.a.s.l.). These agro-ecological zones were also known by the people as Kolla, Woina Dega, Dega, and Wurch, respectively. The mean values of annual temperature range from 7.5 to 22.8 °C and the rainfall from 22.8 to 203.7 mm in the form of bimodal (rain available in two seasons in a year) [11]. Gubalafto District has 139, 825 total population, of which 50.6% are men and 49.4% women [12]. About 3.49% of the population lives in the urban area, and the remaining 96.51%, in the rural area. People mainly depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. There are 51 health centers, of which 9 of them are private and 42 are governmental centers in the District. Acute febrile illness, acute upper respiratory infection, dyspepsia, diarrhea, pneumonia, helminthiasis, diseases of the muscular and skeletal system, trauma, urinary tract infection, infections of the skin, and subcutaneous tissues are the ten major morbidity diseases recorded in the District [13].

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area. a Location of Gubalafto District in Ethiopian. b Sampled and non-sampled kebeles in Gubalafto District. c List and site of sampled kebeles in Gubalafto District

Study sites and informant selection techniques

Study sites and informants were selected based on the information gathered from Gubalafto District administration office, health office, agricultural office, and other people in the study area via reconnaissance survey prior to the data collection. Accordingly, seven kebeles, namely Koso-amba, Ahuntegegn, Woyneye, Geshober, Amaye-mecha, Gubarja, and Hara were selected for data collection with purposive sampling method based on their agro-ecological conditions, the availability of traditional medicine practitioners, and vegetation covers (Fig. 1). Eighty-four informants (12 from each kebele) both males and females, whose ages ranged from 20 to 90 years were interviewed during the study. Informants were selected with purposive, snowball (non-probability), and random (probability) sampling techniques following previous publications [14–16]. The purposive sampling technique was used due to the fact that there were healers that had an official permission for their traditional healthcare practices. Information regarding healers was obtained from each sampled kebele health offices and other people. On the contrary, the snowball sampling technique was used to get hold of healers who had no official permission for their traditional medicinal practices and who were found through the suggestion of other interviewed informants confidentially. As the names of non-legalized healers were not registered in the governmental offices and the people hesitated to report their names freely, the use of a snowball sampling technique was useful.

In the same vein, additional traditional medicinal plant species and associated information were collected from general informants (non-healers) with random sampling techniques. General informants were ordinary people who were found in the study area for a long period of time and used their indigenous medicinal plant knowledge within their families. Hence, general informants were included as respondents to gather additional data and check the transfer of indigenous knowledge within the people. Generally, purposive and snowball samples were used to choose a total of 32 key informants, whereas 52 informants were selected using random sampling method.

It was necessary to follow some steps to contact informants. Firstly, legal supportive letters were obtained from Woldia University research and development office. The District administrators and health and agricultural officials in Gubalafto discussed with the researcher about the objectives of the study. Consequently, they permitted and gave a collaborative letter to conduct the study in the selected kebeles. Thirdly, they sent a letter of research permit for the kebele chairpersons and the personnel of health offices. Accordingly, the lists of officially recognized traditional healers of each kebele were given along with the diseases treated by the kebele health officers. Likewise, group discussions were performed with the people about the importance of the study. Finally, the kebele chairpersons and health officers conveyed messages for the people concerning their participation in the study. Field guides were used to contact healers and collect medicinal plant specimens.

Data collection tools and procedures

Ethnobotanical data were collected from February 2013 to January 2015 in both rainy and dry seasons with a descriptive field survey design in which both qualitative and quantitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews, guided field walks, demonstrations, and focus group discussions. The semi-structure interviews were delivered with the help of pre-prepared questions in the English language. The items of the interview were done on the demographic characteristics of the informants included gender, age, job, educational level, religion, and category (either healers or general informants). Data were also focused on the uses of medicinal plants which incorporated local names, diseases treated, parts used, preparation methods, administration route/s, dosage, habits, and the habitats. The medicinal plant’s conservation practices, adverse effects (if any), taboos (if any), additional uses as wild food and livestock medicines (if any), and indigenous knowledge transfer systems were also included. Individual interviews were also conducted with each key informant for preference ranking exercise following methods used by previous researchers [14–16].

Data were also collected through demonstrations (plant interviews) in the cases of some females and aged male informants in their homes with the help of prior collected plant specimens collected from the field. This is because female and aged male informants had a minimal chance to move to far places to show medicinal plant specimens and their practices. Other informants also showed their medicinal plant practices in their homes and in the fields. One up to two focus group discussions were conducted in each sampled kebele with governmental officials, key informants, and other people with the help of general interview questions. Guided field walks were conducted with interviewed informants and other local indigenous people to search for additional medicinal plants in the wild and to collect medicinal plant voucher specimens. All interviewees were asked in the Amharic language, which is the language of the inhabitants of the study area, and the collected data were translated into English with the help of experts. Contact time and place were selected based on the interest of the informants.

The information about traditional medicinal plant specimens, consequently, was recorded in the notebook, and the plants were pressed with plant press and dried properly. The scientific names of the dried traditional medicinal plant specimen were identified in the National Herbarium (ETH) in Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, by using published volumes of the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea [17–25], by the help of deposited authenticated specimens and taxonomists. Finally, the voucher specimens were deposited in ETH.

Data analysis

Data were organized and analyzed by Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet 2007 and Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20. Independent sample t test was computed to identify the number of medicinal plant species and associated uses reported by healers and general informants. Similarly, it was also used to identify the indigenous knowledge variation of males and females on the numbers of medicinal plant species and associated uses they mentioned. The ages of the informants were grouped into 20–39 (younger informants) and 40–84 (elder informants). Therefore, the variation in the numbers of medicinal plant species and associated uses reported within the two age groups were computed with independent sample t test.

Diseases recorded in this study were grouped into ten major categories with the help of physicians, and informant consensus factor (ICF) was calculated to determine the effectiveness of medicinal plants in each ailment category according to Heinrich et al. [26]. It was calculated by the formula: ICF = Nur − Nt/Nur − 1, where Nur refers to the number of use reports for a particular ailment category and Nt refers to the number of medicinal plant species used for a particular ailment category by all informants.

On the other hand, use value was also calculated to see the relative importance of each traditional medicinal plant species for treating diseases in the study area according to Phillips et al. [27]. It was calculated by the formula UV = ΣUi/n where UV stands for the total use value of the traditional medicinal plant species, whereas U refers to the number of use reports cited by each informant for a given plant species and n stands the total number of informants interviewed for a given plant species.

Fidelity level (FL) was computed to determine the FL values of the most frequently used plant species for treating a particular ailment according to Friedman et al. [28]. It was calculated by the formula FL = Np/N where Np stands for the number of use reports cited for a given species for a particular ailment and N refers to the total number of use reports cited for any given traditional medicinal plant species.

Furthermore, the preference ranking was determined by purposively drawn ten experienced key informants to prioritize the nine traditional medicinal plant species used for preventing bleeding according to Cotton [15]. Bleeding was preferred for ranking because it is a fatal and an emerging disease in the society.

Results

Respondents’ indigenous knowledge characteristics

Of the total 84 informants, the numbers of male participants were higher than those of females. Informants in the age range between 40 and 90 years were the highest in number (75%) and a little higher than half (53.6%) of the informants had gone through modern education (Table 1). The occupation of the informants showed that 83.3% of them were farmers, 6% were students, 3.6% were housewives, and some of the informants were represented with healers and jobless. From the total informants, 39.3% were key informants (healers) and 60.7% were general informants.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the informants

| Sex | Age group (in years) | Educational status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 | 40–90 | Illiterate | Religious education | Modern education | |

| Male | 13 (61.9%) | 55 (87.3%) | 13 (61.9%) | 17 (94.4%) | 38 (84.4%) |

| Female | 8 (38.1%) | 8 (12.7%) | 8 (8.1%) | 1 (5.6%) | 7 (15.6%) |

| Total | 21 (25%) | 63 (75%) | 21 (25%) | 18 (21.4%) | 45 (53.6) |

The great majority of respondents (90%) reported that most of their knowledge was received from their family members and friends secretly. The secret practices of traditional medicines came from their ancestors. However, if it is not practiced secretly, they think that the potential of the medicinal values of the plants will be diminished. Furthermore, five Muslim healers acquired their knowledge through the local graduation (MIRKAN) system from other elder traditional medicine experts. Nevertheless, elders implement this kind of graduation after having observed their activity in practice. The five Muslim healers believed that traditional knowledge shared without local graduation system could not be usable and unsuitable for treating ailments. Furthermore, 60% of the healers reported that they learned their medicinal plant knowledge from their friends in the Orthodox Church schools.

Significant differences (P < 0.05) were obtained by independent sample t test between healers and general informants on the number of medicinal plant species and associated uses (Tables 2 and 3). From the respondent’s report, it was found that some key informants were noticed with few effective remedies that treated one or two ailments like specialized doctors in modern medicines. The test did not show a significant difference (P > 0.05) between male and female informants on the number of medicinal plant species they listed and associated uses reported. However, males reported the highest number of medicinal plant species and associated uses (Tables 2 and 3). The test also confirmed that there was no significant difference on the number of medicinal plant species mentioned by the two age groups (20–39 and 40–84 years) of informants and the respective uses they explained (Tables 2 and 3). However, elders whose ages were between 40 and 84 years noticed detailed descriptions and practical preparation techniques.

Table 2.

Statistical test of significance and independent t test on the number of medicinal plants mentioned by informant groups in Gubalafto District

| Parameters | Informant group | N | No. of plant species reported | Mean | t value** | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant category | General informant | 51 | 303 | 5.94 | − 4.334 | 0.000* |

| Healer | 33 | 541 | 16.39 | |||

| Gender | Male | 68 | 706 | 10.38 | 0.529 | 0.598 |

| Female | 16 | 138 | 8.63 | |||

| Age | Younger(20–39 years) | 21 | 176 | 8.38 | − 0.739 | 0.462 |

| Elder (40–84 years) | 63 | 668 | 10.60 |

*Significant difference (P < 0.05), **t (0.05) (two tailed), df = 82, N= number of respondents

Table 3.

Statistical test of significance and independent t test on the number of medicinal plant use mentioned by informants in Gubalafto District

| Parameters | Informant group | N | No. of plant species uses reported | Mean | t value** | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant category | General informant | 51 | 268 | 5.25 | − 4.406 | 0.000* |

| Healer | 33 | 424 | 12.85 | |||

| Gender | Male | 68 | 581 | 8.54 | 0.676 | 0.501 |

| Female | 16 | 111 | 6.94 | |||

| Age | Younger(20–39 years) | 21 | 162 | 7.71 | − 0.323 | 0.747 |

| Elder (40–84 years) | 63 | 530 | 8.21 |

*Significant difference (P < 0.05), **t (0.05) (two tailed), df = 82, N= number of respondents

On the other hand, traditional healers and members of the society reported that traditional medicinal practices are not encouraged by the kebele governmental offices, which are considered as illegal activities. Some of the healers also reported experiencing derogatory descriptions and scoldings by calling them witchcrafts, KITEL BETASH, SIRMASH, DEBTERA and ASMATEGNA, as explained by the traditional healers, which highly reduced their interests in the traditional medicine practices freely in the society. On the contrary, some of traditional healers are not interested in having governmental legal recognition for their traditional medicine practices due to income taxes that the government levy upon them.

Moreover, 95% of the informants reported that they have not seen any documented material about the traditional medicinal plants of their area and the associated uses. They transferred the knowledge through word of mouth (orally), and through time, they lost part of indigenous knowledge due to the difficulty of memorization. Only 5% of the respondents told that their indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants has been preserved in brief notebooks.

Medicinal plant species of the study area

This study documented 135 traditional medicinal plant species belonging to 120 genera and 64 families, which are used to treat 65 human ailments (Appendix: Table 10). The plant family Asteraceae contributed the highest number of medicinal plant species (11) followed by Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Solanaceae with nine plant species each (Table 4 and Appendix: Table 10).

Table 10.

List of human traditional medicinal plant species, family and vernacular names of the species, number of use reports, use value, ailments treated, plant parts used, condition of preparations, route of administrations, methods of preparations and applications, habit in Gubalafto Districts, Ethiopia

| Sample no. | Family names | Scientific names | Local names | Ha | No. of use report | Use of value (UV) | Ailment treated | PU | Cp | Ra | Methods of preparation and applications | Comparison with similar studies | Ht | CN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acanthaceae | Barleria eranthemoides R. Br. ex C. B. Clarke | Setaf/senkolla | H | 6 | 0.07 | Wound | L | F | D | Crush and tie | 32▼, 50▼, 40▼ | W | GC180 |

| Visual impairment | R | F | Op | Paint the ash together with butter | ||||||||||

| Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) T. Anders. | Sensel | S | 5 | 0.06 | Typhoid and malaria | L | F | O | Crush and squeeze then drink with coffee | 31▲, 38▼, 54▼, 37▼, 50▲, 59▼, 76▼, 68▼, 63▲, 46▲, 65▼, 55▲, 32▼, 70▼, 73▼, 81▲, 83▼ | H | GC154 | ||

| Liver problem | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink | ||||||||||

| Ruellia patula Jacq. | Duaduatie/goregondie | H | 4 | 0.05 | Baldness | Ft | D | D | Use ash to paint together with butter | 71▼, 75▲ | W | GC225 | ||

| Bleeding and wound | L | F | D | Crush and tie | ||||||||||

| Stomach problem | R | F/D | O | Crush and smash in water for 3 days then drink | ||||||||||

| Snake bite | R | F | O | Chew and swallow the juice | ||||||||||

| 2. | Actiniopteridiacae | Actiniopteris dimorpha Pic. Serm. | Esat adrik | H | 2 | 0.02 | Fire burn | All | F/D | D | Paint the ash/crush and wash with juice | – | W | GC211 |

| Alliaceae | Allium sativum L. | Nech shinkurt | H | 11 | 0.13 | Evil eye | Ft | F | N | Crush then sniff | 68▲, 31▼, 37▼, 63▲, 50▼, 36▼, 29▲, 46▼, 78▲, 65▼, 67▲, 80▼, 42▼, 45▲, 70▼, 72▼, 59▲, 77▼, 55▲, 38▲, 73▼, 47▼, 82▼, 83▼ | H | GC011 | |

| Stomachache | L | F | O | Chew and swallow | ||||||||||

| 3. | Aloaceae | Aloe weloensis Sebsebe | Eret tafa | H | 4 | 0.05 | Wound | Lx | F | D | Paint | – | WH | GC210 |

| Malaria | Lx | F | O | Isolate and drink | ||||||||||

| ABO incompatibility | R | D | O | Powderize and mix with honey then drink | ||||||||||

| 4. | Amaranthaceae | Achyranthes aspera L. | Telenge | H | 19 | 0.23 | Wound | L | F | D | Pound and tie | 2▲, 31▲, 49▼, 63▲, 50▼, 78▲, 46▼, 40▼, 65▼, 66▼, 67▼, 45▼, 48▼, 70▼, 71▲, 73▲, 59▼, 38▼, 82▲, 83▼, 84▲ | WH | GC025 |

| Fever | L | F | DNO | Boil the concoction then fumigate the fume | ||||||||||

| Eye dusts and ear mites | L | F | Op, N | Squeeze the concoction then drop using cotton | ||||||||||

| Tonsillitis | L | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice with coffee | ||||||||||

| Excessive bleeding after birth | L | F | Vl | Rub and insert then cover with cloth | ||||||||||

| 5. | Anacardaceae | Rhus retinorrhoea Oliv. | Talo enbis | T | 1 | 0.01 | Tonsillitis | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink | 50▼, 78▼ | W | GC187 |

| Stomachache | R | D | O | Crush and smash in water for 3 days then drink the filtrate with honey | ||||||||||

| Schinus molle L. | Kundoberberie | T | 2 | 0.02 | Common cold | L | F | N | Rub and sniff | 31▼, 38▼, 63▲, 78▼, 77▼, 46▼, 70▼, 73▼, 47▼ | H | GC155 | ||

| 6. | Apiaceae | Agrocharis melanantha Hochst. | – | H | 1 | 0.01 | Stomachache | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | 29▼ | W | GC209 |

| Ferula communis L. | Dog | H | 2 | 0.02 | Impotency | R | F/D | O | Powderize the concoction then drink with Tella | 78▼, 59▼, 63▲, 46▼ | W | GC072 | ||

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Ensilal | H | 4 | 0.05 | Headache | R | F | O | Crush, mash, and filtrate then drink | 31▲, 38▼, 54▲, 50▼, 42▲, 63▼, 68▲, 46▼, 65▼, 70▼, 80▼, 35▲, 82▼, 83▲ | WH | GC137 | ||

| Tooth and stomachache | R | D | O | Crush, mash, boil, and filter then drink | ||||||||||

| Kidney infection | L | F | O | Decoct and filter then drink | ||||||||||

| 7. | Apocynaceae | Acokanthera schimperi (A.DC.) Schweinf. | Miriez | S | 1 | 0.01 | Wound | L | D | D | Crush then paint | 32▼, 63▼, 50▼, 40▼, 65▼, 45▼, 59▲, 77▼, 79▼, 38▲, 73▼, 81▼ | W | GC047 |

| Carissa spinarum L. | Agam | S | 7 | 0.08 | Snake poison | L | F | O | Chew and swallow | 31▲, 38▼, 50▲, 37▲, 59▲, 76▼, 63▼, 61▼, 68▼, 65▲, 29▲, 46▼, 45▼, 70▼, 79▼, 40▲, 78▼, 73▲, 47▲, 81▲, 82▼, 83▲ | W | GC021 | ||

| Evil spirit | R | D | N | Crush and fumigate | ||||||||||

| Stomachache | R | F/D | O | Crush, mash, and filter then drink | ||||||||||

| 8. | Arecaceae | Phoenix reclinata Jacq. | Sensel | S | 3 | 0.04 | Sexual diseases | R | D | O | Powderize the concoction then drink with honey and butter | 68▼, 77▼ | WH | GC201 |

| 9. | Asclepiadaceae | Calotropis procera (Ait.) Ait.f. | Tobia | S | 4 | 0.05 | Eczema | Lx | F | D | Paint | 38▲, 78▼, 9▼, 75▼▲, 33▼, 36▼, 51▼, 72▲, 63▲, 77▼, 66▲, 58▲, 73▼, 82▲, 83▼, 84▼ | W | GC035 |

| Hemorrhoid | Lx | F | D | Paint | ||||||||||

| Huernia macrocarpa (A.Rich) Sprenger | Yemidir kulkual | H | 1 | 0.01 | Skin cancer | Lx | F | D | Mix with Sumanfar then insert at the spot | – | W | GC100 | ||

| 10. | Asteraceae | Artemisia absinthium L. | Natra | H | 5 | 0.06 | Evil eye | L | F | N | Rub and sniff | 68▼, 29▲, 46▼, 35▼, 73▲ | H | GC176 |

| Tonsillitis | L | F | O | Squeeze the concoction then drink | ||||||||||

| Artemisia afra Jack. ex Willd. | Chikugn | H | 5 | 0.06 | Evil eye | All | F | N | Sniff | 68▼, 63▲, 50▲, 42▼, 45▼, 70▲, 76▼, 48▼, 38▲, 84▼ | H | GC168 | ||

| Bidens pilosa L. | Yeseytan merfie | H | 2 | 0.02 | Evil spirit | All | F/D | DNO | Fumigate | 53▼, 72▼, 29▼, 46▲, 70▼ | W | GC184 | ||

| Carduus chamaecephalus (Vatke.) Oliv. & Hiern | Kushele/dendero | H | 7 | 0.08 | Febrile illness | R | F/D | DNO | Crush and mash then paint body with extract/decoct then fumigate | 68▼ | W | GC197 | ||

| Cirsium englerianum O. Hoffm. | Kushele | H | 1 | 0.01 | Intestinal parasite | R | D | O | Powderize the concoction and drink with honey. After a few minutes, drink local beer (Tella) | 63▼ | W | GC050 | ||

| Conyza schimperi Sch. Bip. ex A. Rich | Wereza ktel | H | 2 | 0.02 | Febrile illness | All | F | DNO | Decoct the concoction and fumigate | – | WH | GC215 | ||

| Guizotia abyssinica (L.f.) Cass. | Nug | H | 1 | 0.01 | Gastric | Sd | D | O | Chew and swallow | 37▼, 65▼ | W | GC226 | ||

| Haplocarpha rueppelii (sch.Bip.) Beauv. | Getn | H | 1 | 0.01 | Bleeding | L | F | D | Rub and tie | – | W | GC232 | ||

| Inula confertiflora A. Rich. | Weinagift | S | 3 | 0.04 | Toothache | L | F | O | Take into the mouth, chew ,for a few minutes, and spit then drink coffee | 46▼, 65▼ | WH | GC220 | ||

| Tonsillitis | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink | ||||||||||

| Kleinia abyssinica (A. Rich.) A. Berger | Este-maza | H | 3 | 0.04 | Brain weakness | R | F/D | O | Crush the concoction until powderized, mix honey, boil to distillate, and drink | 79▼, 40▼ | W | GC190 | ||

| Vernonia amygdalina Del. in Caill. | Grawa/merari kelewa | S | 2 | 0.02 | Gout | L | F | DNO | Fumigate | 31▼, 38▼, 79▼, 78▼, 37▼, 50▼, 36▼, 54▼, 40▼, 72▼, 42▼, 76▼, 63▼, 61▼, 68▼, 29▼, 45▼, 70▼, 65▼, 81▼, 82▼, 83▼ | WH | GC055 | ||

| 11. | Balanitaceae | Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. | Bedena | T | 3 | 0.04 | Dandruff | L | F | D | Crush the concoction then paint | 32▼, 40▼, 70▼, 75▼, 83▼ | WH | GC240 |

| Stomachache | L | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| 12. | Boraginaceae | Cordia africana Lam. | Wanza | T | 1 | 0.01 | Eczema | L | F/D | D | Paint the concoction ash together with butter | 31▲, 38▼, 78▼, 30▼, 48▼, 54▼, 42▼, 63▼, 68▼, 40▼, 77▼, 45▼, 70▼, 73▼, 47▼ | WH | GC133 |

| Cynoglossum coeruleum Hochst. ex A. DC. | Chugagot | H | 21 | 0.25 | Febrile illness | L | F | DNO | Decoct the concoction then fumigate | 31▲, 38▲, 63▲, 47▲, 81▲ | W | GC114 | ||

| Eye problem | L | F/D | N | Crush concoction then insert in the nasal tube | ||||||||||

| Febrile illness | L | F | D, N | Squeeze then paint the body and drink with honey | ||||||||||

| Heliotropium cinerascens D.C. | Nechilo | H | 5 | 0.06 | Wound | L | F | D | Crush and tie | 83▼ | W | GC199 | ||

| Eye mites | L | F | Op | Crush the concoction, squeeze, filtrate, and insert | ||||||||||

| 13. | Brassicaceae | Brassica oleracea L. | Tikle gomen | H | 1 | 0.01 | Gastric | L | D | O | Powderize, mix honey for 2 days then eat | 49▼ | H | GC191 |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Fetto | H | 2 | 0.02 | Febrile illness | Sd | D | DNO | Burn the concoction and fumigate | 31▼, 38▼, 54▲, 50▼, 42▼, 68▼, 77▼, 29▼, 65▲, 45▼, 55▼, 78▼, 73▲, 65▼, 81▼, 84▼ | H | GC213 | ||

| 14. | Capparidaceae | Boscia salicifolia Olive. | Tisha | T | 2 | 0.02 | Ear mites | L | F | O | Squeeze and mix lemon juice then drink | 40▼, 33▲, 73▼ | W | GC179 |

| Eye problem | L | F | Op | Squeeze and filtrate then insert | ||||||||||

| Capparis tomentosa Lam. | Gimero | Cl | 3 | 0.04 | Evil eye and evil spirit | R | F/D | DNO | Crush then fumigate | 62▼, 38▲, 50▲, 53▼, 37▼, 59▲, 63▲, 77▲, 46▼, 40▼, 55▲, 70▼, 78▼, 73▲, 47▼, 81▲, 83▼ | W | GC023 | ||

| 15. | Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Papya | T | 1 | 0.01 | Intestinal parasite | Sd | D | O | Powderize then eat with honey | 49▼, 1▼, 40▼, 38▼, 53▼, 65▼, 36▼, 72▼, 30▼42▲, 59▼, 63▼, 68▼, 77▼, 58▼, 69▼, 70▲, 78▲, 73▼, 83▲ | H | GC098 |

| 16. | Celastraceae | Catha edulis (Vahl) Forssk. ex Endl. | Chat | S | 1 | 0.01 | Intestinal parasite | L | F | O | Decoct then drink the extract | 48▼, 54▼, 37▲, 68▼, 65▼, 46▼, 40▼, 45▼, 55▼, 70▼, 78▼, 47▼ | H | GC196 |

| 17. | Chenopodiaceae | Chenopodium murale L. | Amedmado | H | 1 | 0.01 | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | R,L | D | D | Point the concoction ash | 38▼, 51▼, 63▼, 73▲ | W | GC136 |

| 18. | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe laciniata (L.) DC. | Endahula/shilkak | H | 2 | 0.022 | Swelling | L | F | D | Heat and apply on the spot | 37▲, 63▼, 40▼ | W | GC084 |

| Broken bone | L | F | O | Heat and rub the target part | ||||||||||

| Expelled uterus | L | F | Vl | Crush and pushed inside | ||||||||||

| Hip obesity | R | F | D | Crush the concoction then paint and rub | ||||||||||

| Tonsillitis | R | F | N | Peal and chew or sniff | ||||||||||

| Toothache | R | F | O | Take into the mouth, chew for a few minutes then spitted out and drink coffee | ||||||||||

| 19. | Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis ficifolius A. Rich. | Yemdir enboy | H | 11 | 0.13 | Dactylitis | Ft | F | D | Make a hole and insert it | 31▼, 38▼, 79▼, 37▲, 50▼, 78▼, 59▲, 63▲, 46▲, 40▲, 65▲, 70▼, 73▼, 81▲, 82▼ | W | GC139 |

| Hemorrhoids | R | F/D | D | Crush, mix with honey then tie | ||||||||||

| Rabies | R | D | O | Powderize then drink with water and milk | ||||||||||

| Stomachache | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| Cucurbita pepo L. | Duba | Cl | 1 | 0.01 | Excessive bleeding after birth and menstruation | R | D | O | Powderize and drink with water | 31▼, 38▼, 50▼, 48▼, 37▼, 63▼, 77▼, 29▼, 70▼, 65▼, 78▼, 83▼ | H | GC166 | ||

| Swelling | R,L | F | D | Roast then paint and tie | ||||||||||

| Kedrostis gijef (Forssk.)C. Jeffrey | Ergobergo | Cl | 1 | 0.01 | Swelling | L | F/D | D | Crush and powderize then paint | – | W | GC228 | ||

| Zehneria scabra (Linn. f.) Sond.. | Hareg resa/ harresa | H | 18 | 0.21 | Febrile illness | L | F | DNO | Squeeze the concoction then cream | 38▲, 50▼, 78▲, 53▼, 37▲, 63▲, 46▼, 68▲, 65▼, 81▼, 84▼ | WH | GC149 | ||

| Wound | L | F | D | Powderise then cream | ||||||||||

| Febrile illness | L | F | DNO | Boil and fumigate | ||||||||||

| Liver problem | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink with water | ||||||||||

| 20. | Ebenaceae | Euclea racemosa Murr. | Dedeho | S | 1 | 0.01 | Dysuria | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink with honey | 63▼, 50▼, 46▼, 32▼, 79▼, 73▼, 83▼ | W | GC018 |

| Dandruff | R | F/D | D | Paint the ash together with butter | ||||||||||

| 21. | Euphorbiaceae | Clutia lanceolata Forssk. | Fiyelefej | S | 4 | 0.05 | Evil eye | R | F/D | D | Crush the concoction then tie | 31▼, 63▼ | W | GC135 |

| Excessive bleeding after birth | R | F | O | Crush, mash for 3 days, and filtrate then drink | ||||||||||

| Croton macrostachyus Del. | Mekanisa | T | 24 | 0.29 | Liver problem | B | F/D | O | Powderize the concoction then drink with honey | 31▲, 40▼, 61▼, 68▲, 77▼, 59▲, 76▲, 63▲, 57▲, 48▼, 54▲, 37▲, 42▲, 29▲, 46▲, 45▲, 55▲, 70▲, 79▲, 65▲, 38▲, 78▲, 47▼, 81▲, 82▲, 83▲ | W | GC130 | ||

| Stomachache | B | D | O | Crush and eat with honey | ||||||||||

| Gonorrhea | B | F | O | Squeeze then drink. After a few minutes, eat hen heart or drink Tella | ||||||||||

| Malaria | Ft | F | O | Crush and mash then drink with Tella | ||||||||||

| Atopic dermatitis | L | F | D | Squeeze the sap then paint | ||||||||||

| Epidemic | L | F/D | DNO | Burn and fumigate | ||||||||||

| Febrile illness | L | F/D | DNO | Crush, decoct, and fumigate | ||||||||||

| Euphorbia abyssinica Gmel. | Kulkual | T | 3 | 0.04 | Take out spine | Lx | F | D | Take the latex then paint on the spot | 50▼, 59▼, 63▼, 78▼, 46▼, 45▲, 73▼, 81▼ | WH | GC164 | ||

| Stomach problem | Lx | F | O | Take the latex, bake with bread then eat | ||||||||||

| Euphorbia tirucalii L. | Kinchib | S | 2 | 0.02 | Tinea versicolor | Lx | F | D | Take the latex then paint | 54▼, 37▼, 50▼, 42▼, 59▲, 77▼, 63▲, 29▼, 46▼, 69▼, 35▲, 73▼, 47▼, 83▼ | WH | GC131 | ||

| Wound | R | D | D | Powderize then paint | ||||||||||

| Ricinus communis L. | Chakima/ Gulo | S | 2 | 0.02 | Ear mites | L | F | Er | Squeeze and insert | 31▼, 38▼, 79▼, 50▼, 9▼, 57▼, 49▼, 40▼, 48▼, 54▼, 72▼, 42▼, 68▼, 77▼, 29▼, 46▼, 55▼, 67▼, 80▼, 66▼, 65▼, 70▼, 78▼, 59▼, 73▼, 47▼, 81▲, 83▼, 84▼ | H | GC170 | ||

| Stomachache | R | F/D | DNO | Fumigate | ||||||||||

| Tragia brevipes Pax. | Awulalit | H | 7 | 0.08 | Dactylitis | R | D | D | Crush, powderize, and add butter then tie | 63▼ | W | GC013 | ||

| Impotency | R | F/D | O | Chew and absorb the juice | 63▲, 40▼ | |||||||||

| Stomachache | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| Retained placenta | R | F | Vl | Crush and insert in a cloth through the vaginal tube | ||||||||||

| 22. | Fabaceae | Acacia seyal Del. | Duret | T | 7 | 0.08 | Dandruff | L | F | D | Crush and paint with water | 32▼, 46▼, 53▼, 40▼, 45▼, 70▲ | WH | GC229 |

| Wound | L | F | D | Chew and tie/cream | ||||||||||

| Swelling | L | F | D | Crush and tie | ||||||||||

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait.) Benth. | Digita | S | 1 | 0.01 | Excessive bleeding after birth | R | F/D | O | Crush or powderize the concoction then drink with water | 38▼, 31▼, 37▼, 50▼, 59▼, 76▼, 63▲, 68▼, 77▼, 29▼, 46▼, 55▼, 70▼, 40▼, 65▼, 73▼, 81▼, 83▲ | WH | GC020 | ||

| Cicer arietinum L. | Shinbira | H | 1 | 0.01 | Malaria | Sd | D | O | Germinate then eat the concoction. | 63▲, 68▼ | WH | GC115 | ||

| Indigofera brevicalyx Bak.f | – | H | 3 | 0.04 | Snake poison | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | – | W | GC221 | ||

| Indigofera spicata Forssk. | – | H | 4 | 0.05 | Snake bite and poison | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | 50▼, 61▼, 68▲, 29▼, 40▼, 45▲, 82▼ | W | GC205 | ||

| Melilotus suaveolens Ledeb. | Egug | H | 2 | 0.02 | Herpes zoster | L | D | O | Crush and drink with water | – | W | GC186 | ||

| Senna septemtrionalis (Viv.) Irwin & Barneby | – | S | 1 | 0.01 | Cough, lung cancer, and brain problem | L | F | D | Crush, smash in water, filter then drink | 40▼ | W | GC189 | ||

| Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | Abish | H | 1 | 0.01 | Gastric | Sd | D | O | Grind, mix with water, and drink | 38▲, 78▲, 73▲ | WH | GC181 | ||

| Vicia faba L. | Bakela | H | 6 | 0.06 | Boils/furunclosis | Sd | D | D | Crush with teeth then paint | 63▼, 80▼, 47▼, 84▲ | WH | GC109 | ||

| Nerve problem | Sd | D | D | Grind and mix butter then paint and stay on sunlight | ||||||||||

| 23. | Geraniaceae | Geranium arabicum Forssk. | Mencherer | H | 7 | 0.08 | Febrile illness | R | D | DNO | Crush the concoction, decoct, and use fume to fumigate | 50▼, 29▲ | W | GC203 |

| Stomachache | R | F | O | Crush, decoct, and filter then drink | ||||||||||

| 24. | Gingibraceae | Zingiber officinale Rosc. | Gingible | H | 5 | 0.06 | Stomachache | R | F | O | Chew and swallow the juice/drink with tea | 38▼, 36▼, 72▼, 37▼, 42▲, 61▼, 68▲, 77▲, 45▲, 67▲, 58▼, 74▼, 70▼, 65▼, 78▲, 81▲, 84▼ | H | GC231 |

| Swelling | L | F | D | Chew and tie | ||||||||||

| 25. | Hypericaceae | Hypericum quartinianum A.Rich | Amujia | S | 2 | 0.02 | Eczema | R | F/D | D | Crush and mix with 1-year stayed ash and camel’s feces then paint with butter | 50▼, 46▼ | W | GC224 |

| Stomachache | R,L | F/D | O | Crush and immerse in water then drink | ||||||||||

| 26. | Lamiaceae | Ajuga integrifolia Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don | Tut astil | H | 2 | 0.02 | Tonsillitis | L | F | O | Rub and squeeze then drink | 46▼, 45▼, 70▼, 73▼ | W | GC214 |

| Clerodendrum myricoides (Hochst.) Vatke | Misroch | S | 3 | 0.04 | Wound | L | F/D | D | Crush the concoction and tie/rub and tie alone | 31▼, 38▼, 50▼, 3▼, 53▼, 48▼, 76▼, 63▼, 61▼, 68▼, 77▼29▼, 46▲, 40▼, 70▼, 78▼, 73▼, 83▼ | W | GC016 | ||

| Leonotis ocymifolia (Burm.f.) Iwarsson | Ferezeng | S | 5 | 0.06 | Brain problem | L | F/D | O | Crush the concoction and immerse in water then drink with honey | 38▼, 50▼, 78▼ | W | GC192 | ||

| Swelling | L | D | O | Crush until powderized then drink with water | ||||||||||

| Meriandra dianthera (Roth ex Roem & schult.) Briq. | Mentese | S | 3 | 0.04 | Trachoma | Fr | D | Op | Burn the concoction and paint the eye with the ash | 38▼ | WH | GC194 | ||

| Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex Benth. | Dama kesie/alemsela | S | 30 | 0.36 | Headache, febrile illness | L | F | O | Cook and drink with coffee | 31▲, 38▲, 79▼, 57▼, 54▼, 50▲, 42▼, 59▲, 76▼, 63▲, 61▼, 68▼, 29▼, 46▲, 45▲, 70▲, 65▲, 78▼, 81▲, 83▲, 84▲ | WH | GC129 | ||

| Febrile illness | L | F | DNO | Burn the concoction and fumigate | ||||||||||

| Plectranthus cylinderaceus Hochst. ex. Benth | Tsezeteza | H | 6 | 0.06 | Stomach problems | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink | 29▼, 32▼ | WH | GC206 | ||

| Plectranthus lanuginosus (Hochst. ex Benth.) Agnew | Aguacher | H | 3 | 0.04 | Expel dusts in the eye | L | F | Op | Rub and drop the fluid then cover with cotton | – | W | GC216 | ||

| Salvia merjamie Forssk. | Shehara kitel | H | 1 | 0.01 | Bleeding | L | F | D | Rub and tie/paint | 31▼ | WH | GC204 | ||

| Salvia nilotica Jacq. | – | H | 2 | 0.02 | Bleeding | L | F | D | Squeeze then tie | 68▲, 50▼, 46▼, 45▼ | W | GC233 | ||

| Ear mites | L | F | Er | Squeeze then cover with cotton | ||||||||||

| 27. | Lobeliaceae | Lobelia gibberoa Hemsl. | Jibara | T | 3 | 0.04 | Eye problem | R | F/D | O | Crush and immerse in water then drink | W | GC119 | |

| Impotency | R | F/D | O | Crush then mix with coffee and drink | ||||||||||

| Malaria | R | F/D | O | Crush and powderize then drink with water | ||||||||||

| Epilepsy | Sd | D | O | Give with Teff injera | ||||||||||

| 28. | Loranthaceae | Englerina woodfordioides (Schweinf.) Balle | Yekinchib teketila | H | 4 | 0.05 | Wound | L | D | D | Powder then paint | 55▼ | WH | GC200 |

| Oncocalyx schimperi (A.Rich.)M Gilbert | Yebedena teketila | H | 1 | 0.01 | Dactylitis | L | F | D | Chew the concoction then tie | – | W | GC202 | ||

| 29. | Malavaceae | Sida tenuicarpa Vollesen | Chifrg | H | 2 | 0.02 | Eye problem | R | F | Op | Crush the concoction, squeeze, and insert | 63▼ | W | GC153 |

| Gossypium barbadense L. | Tit | S | 1 | 0.01 | Eczema | Sd | D | D | Mix ash with honey then tie | 63▼, 29▼ | H | GC096 | ||

| 30. | Melianthaceae | Bersama abyssinica Fresen. | Azamir | S | 2 | 0.02 | Rabies | R and L | F/D | O | Crush the concoction then drink with milk | 78▼, 48▼, 54▼, 37▼, 40▼, 65▼, 42▼, 63▼, 29▼, 31▼, 70▼ | W | GC107 |

| 31. | Menispermaceae | Stephania abyssinica (Dillon & A. Rich.) Walp. | – | H | 4 | 0.05 | Intestinal parasite | R | D | O | Powderize the concoction then drink with honey. After a few minutes, drink Tella | 31▼, 59▼, 63▼, 50▼, 78▼, 68▼, 40▼65▼, 46▼, 47▼ | W | GC121 |

| 32. | Mersinaceae | Myrsine africana L. | Kechemo | S | 1 | 0.01 | Stomachache | R and L | F/D | O | Crush, immerse in water, and mix with butter and honey then drink | 50▼, 78▼, 76▼, 29▼, 46▼, 40▼, 65▼, 55▼ | W | GC217 |

| 33. | Moraceae | Ficus carica L. | Beles | S | 3 | 0.04 | Eczema | L | F/D | D | Powder paint with butter/tie | 31▼, 63▼, 80▲ | W | GC104 |

| Ficus sur Forssk. | Sholla | T | 2 | 0.02 | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | R,L | D | D | Powderize the concoction then paint with honey | 1▼, 31▼, 48▼, 63▼, 46▲ | W | GC090 | ||

| Ficus vasta Forssk. | Warka | T | 2 | 0.02 | Stomachache | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | 31▼, 63▼, 68▼ | W | GC162 | ||

| 34. | Moringaceae | Moringa stenopetala (Bak.f.) Cuf. | Shiferaw | T | 2 | 0.02 | Hypertension | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink/crush then boil, filtrate, and drink | 54▼, 68▲, 29▼, 70▲ | WH | GC178 |

| 35. | Myricaceae | Myrica salicifolia A. Rich. | Shinet | T | 2 | 0.02 | Evil eye and evil spirit | B | D | N | Crush powder then sniff with the nose | 63▼, 65▼, 46▼ | W | GC106 |

| Liver problem | B | F/D | O | Crush the concoction and drink with honey | ||||||||||

| Joint pain | Rb | D | O | Crush and powderize then drink with honey | ||||||||||

| 36. | Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Nech bahirzaf | T | 28 | 0.33 | Febrile illness | L | F | DNO | Decoction and fumigate | 31▲, 38▲, 50▲, 53▼, 54▲, 37▲, 42▲, 63▲, 68▼, 77▼, 46▲, 55▼, 67▲, 80▼, 65▼, 70▼, 78▼, 73▲, 83▲, 84▲ | WH | GC167 |

| Common cold | L | F | DNO | Decoction then fumigate | ||||||||||

| Appetite | L | D | O | Powderize the concoction and drink the decoction | ||||||||||

| 37. | Olacaceae | Ximenia americana L.. | Enkoy | S | 3 | 0.04 | Swelling | R and L | F | O, D | Chew and swallow the leaf/crush the root and tie | 63▼, 77▼, 40▼, 75▼, 47▼, 81▲, 83▼ | W | GC054 |

| Stomachache | R | F | O | Powder ize then drink with water | ||||||||||

| 38. | Oleaceae | Jasminum abyssinicum Hochest. ex DC. | Tenbelel | Cl | 3 | 0.04 | Eye problem | L | F | Op | Crush and squeeze the concoction then insert with cotton | 63▼, 65▼, 77▼ | W | GC012 |

| Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata L. | Woira | T | 1 | 0.01 | Dandruff | R | F/D | D | Crush and paint the concoction/crush and paint alone | 31▼, 38▼, 50▼, 53▼, 34▼, 40▼, 48▼, 63▼, 46▼, 45▲, 80▼, 75▼, 70▼, 65▼, 47▼, 81▼ | W | GC079 | ||

| 39. | Oliniaceae | Olinia rochetiana A. Juss. | – | T | 1 | 0.01 | Eczema | L | F | D | Crush and tie | 50▼, 48▼, 46▼, 40▼, 65▼, 70▼ | WH | GC219 |

| 40. | Oxalidaceae | Oxalis corniculata L. | Yebere chew | H | 1 | 0.01 | Tinea versicolor | L | F | D | Rub until recovery | 70▼, 71▼ | W | GC227 |

| 41. | Phytolaccaceae | Phytolacca dodecandra L’Her. | Mehan Endod | Cl | 3 | 0.04 | Rabies | R | F/D | O | Grind then drink with water | 31▲, 38▲, 63▲, 50▼, 78▼, 61▲, 68▲, 77▲, 40▼, 42▲, 59▼, 48▲, 54▲, 37▼, 29▼, 46▼, 55▼, 70▼, 65▼, 47▲, 81▲ | W | GC024 |

| Ascariasis | R | F/D | O | Crush the concoction, mix water then drink | ||||||||||

| Malaria | R | F | O | Crush the concoction and drink with water | ||||||||||

| Liver problem | R | F | O | Crush the concoction, mix water, filtrate then drink | ||||||||||

| Prevent snake poison | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink with honey | ||||||||||

| 42. | Plantaginaceae | Plantago lanceolata L. | – | H | 3 | 0.04 | Spider poison | L | F | D | Powderize then paint together with butter | 31▼, 38▼, 63▼, 50▼, 61▼, 77▼, 46▼, 65▼, 55▲, 70▼, 47▼ | WH | GC117 |

| Herpes zoster | L | F/D | D | Powderize then paint | ||||||||||

| 43. | Plumbaginaceae | Plumbago zeylanica L. | Amera | H | 4 | 0.05 | Hemorrhoid | L | F | D | Rub and tie | 31▼, 38▼, 62▲, 79▼, 53▼, 40▼, 9▼, 63▲, 29▲, 70▼, 71▼59▼, 81▲ | W | GC128 |

| Snake bite | R | F/D | D | Take in the pocket when moving | ||||||||||

| Wound | St,L | D | D | Burn and paint together with butter | ||||||||||

| 44. | Podocarpaceae | Podocarpus falcatus L. | Zigiba | T | 1 | 0.01 | Asthma | Sb | D | O | Powderize, mix water, and put it 7 days in the ground then drink | 50▼, 40▼, 65▼, 70▼, 81▼ | H | GC212 |

| 45. | Polygalaceae | Polygala sphenoptera Fresen. | Kibie zelzil | H | 3 | 0.04 | Snake poison, malaria | R | F/D | O | Peel, chew, and absorb the juice | – | W | GC208 |

| Stomachache | R | F/D | O | Chew and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| 46. | Polygonaceae | Rumex abyssinicus Jacq. | Mekmeko | H | 1 | 0.01 | Expel delayed embryo in the uterus | R | D | O | Powderize the concoction and add water then drink | 31▼, 38▼, 37▼, 63▼, 68▲, 50▼, 77▲, 46▼, 70▼, 78▼, 47▼ | W | GC076 |

| Intestinal parasite | R | D | O | Powderize the concoction and add honey then drink. Drink Tella a few minutes later | ||||||||||

| Rumex nepalensis Spreng. | Tult | H | 13 | 0.16 | Over blood flow after birth | L | F | – | Cut and drop on ground | 31▼, 42▲, 59▼, 63▲, 68▲, 50▼, 54▲, 46▲, 40▼, 65▼, 45▲, 78▼, 73▼ | W | GC029 | ||

| Dandruff | R | F | D | Crush then wash with it | ||||||||||

| Stomachache | R | F | O | Crush and smash in, water then drink | ||||||||||

| Stomachache | R | F/D | O | Powderize the concoction and eat with butter | ||||||||||

| Bleeding and wound | L | F | D | Crush the concoction then tie/rub and tie alone | ||||||||||

| Rumex nervosus Vahl | Enbuacho | S | 8 | 0.1 | Warts | L | F/D | D | Crush the concoction, heat and put on the spot | 31▼, 38▼, 50▼, 37▼, 63▲, 46▼, 78▼, 84▼ | W | GC177 | ||

| Wound | L | F/D | D | Crush then tie | ||||||||||

| Fire burn | R | D | D | Powderize then paint | ||||||||||

| 47. | Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Antra | H | 1 | 0.01 | Hemorrhoid | L | F | D | Crush the concoction, mix with salt, and smash in water then tie on the spot | 79▼, 32▼, 40▼ | W | GC193 |

| 48. | Pteridiaceae | Pteris dentata Forsskal | Jero asfit | H | 2 | 0.02 | Eczema | L | F/D | D | Burn and paint the powder | – | W | |

| 49. | Ranunculaceae | Clematis simensis Fresen. | Azo hareg | Cl | 1 | 0.01 | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | R | D | D | Powderize the concoction then paint together with honey | 31▼, 63▼, 50▼, 78▼, 46▲, 40▼, 83▼ | W | GC043 |

| Ranunculus stagnalis Hochst. Ex A. Rich. | Gudign | H | 4 | 0.05 | Eczema | L | F/D | D | Crush the concoction then paint with butter | – | W | GC182 | ||

| Wound | L | F | D | Mix ash with butter then paint | ||||||||||

| Thalictrum rhynchocarpum Dill. & A. Rich. | Sire-bizu | H | 3 | 0.04 | Stomachache | R | F | O | Crush then smash in water, filtrate and drink | 63▼, 50▼, 40▼, 65▼ | W | GC078 | ||

| 50. | Rhamnaceae | Rhamnus prinoides L’Her. | Gesho | S | 18 | 0.21 | Tonsillitis | L | F | O | Squeeze and drink | 31▲, 38▲, 50▲, 57▼, 34▼, 37▲, 59▼, 63▲, 68▲, 65▲, 77▲, 29▲, 45▼, 47▲, 84▲ | H | GC094 |

| Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf. | Kunkura/orsamisa | S | 8 | 0.1 | Anthrax | L | F/D | O | Crush the concoction and add honey then eat | 38▲, 79▼, 50▼, 51▼, 63▲, 77▲, 32▼, 75▼, 84▲ | W | GC163 | ||

| Dandruff | L | F/D | D | Crush and paint | ||||||||||

| 51. | Rosaceae | Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F.Gmelin | Koso | T | 3 | 0.04 | Intestinal parasite | Ft | F/D | O | Crush then eat with honey | 31▲, 54▲, 37▲, 50▲, 42▲, 59▲, 29▲, 65▲, 55▲, 70▲, 47▲, 82▲ | WH | GC183 |

| 52. | Rubiaceae | Coffea arabica L. | Bunna | S | 1 | 0.01 | Asthma | Sd | D | O | Decoct and filtrate then drink | 53▼, 40, ▼, 37▲, 63▼, 68▼, 67▼, 65▼, 80▼, 56▼, 35▲, 38▼ | H | GC161 |

| Galium simense Fresen. | Ashekt | H | 1 | 0.01 | Tinea versicolor | L | F | D | Squeeze the concoction and paint until recovery | 76▲ | W | GC195 | ||

| Rubia cordifolia L. | Mencherer | Cl | 6 | 0.06 | Broken bonee | L | F | D | Crush then tie with butter | 31▼, 62▼, 48▲, 50▲, 63▲, 46▲, 40▼, 71▼ | W | GC110 | ||

| Cough, TB, lung cancer | R | D | O | Crush and smash in water in 3 days then drink | ||||||||||

| Cough | L | F/D | O | Powderize the concoction then drink with honey | ||||||||||

| 53. | Rutacea | Citrus aurantifolia (Christm.) Swingle | Lomy | S | 5 | 0.06 | Acne | Ft | F | D | Squeeze and paint the juice | 49▲, 37▼, 3▼, 60▼, 36▼, 63▼, 68▲, 29▲, 46▲, 65▼, 45▼, 55▼, 58▼, 69▲, 35▼, 74▼, 70▼, 73▲, 83▲ | H | GC169 |

| Stomach problem | Ft | F | O | Squeeze and drink | ||||||||||

| Tinea versicolor | L | F | D | Squeeze the concoction then paint | ||||||||||

| Citrus medica L. | Tirngo | T | 1 | 0.01 | Appetite | Ft | D | O | Powderize the concoction then drink the decoction | 40▼, 60▼, 69▲ | H | GC185 | ||

| Clausena anisata (Willd.) Benth. | Linbich | S | 2 | 0.02 | Evil spirit | R | D | DNO | Crush and fumigate | 1▼, 48▼, 59▼, 76▼, 63▼, 46▼, 47▲, 81▲ | W | GC235 | ||

| Ruta chalepensis L. | Tenadam | H | 14 | 0.15 | Stomachache | Ft, L | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | 31▼, 38▲, 54▲, 37▲, 42▲, 59▲, 63▲, 68▲, 50▲, 40▼, 77▼, 29▲, 46▲, 45▲, 70▼, 65▼, 78▲, 47▲, 82▲, 83▲, 84▼ | H | GC236 | ||

| Evil eye | Ft,L,St | F/D | O | Chew and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| 54. | Santalaceae | Osyris quadripartita Salzm. ex Decne | Keret | S | 2 | 0.02 | Rabies | R | F | O | Crush the concoction then drink with milk | 31▼, 68▼, 79▲, 50▼, 78▼, 40▼, 46▼, 65▼ | W | GC237 |

| Thesium kilimandscharicum Engl. | – | H | 1 | 0.01 | Dactylitis | All | F/D | D | Burn and paint the ash | – | W | GC218 | ||

| 55. | Sapindaceae | Dodonaea angustifolia L.f. | Kitkita | S | 3 | 0.04 | Trachoma | R | D | Op | Paint the concoction ash | 31▲, 38▲, 54▼, 37▼, 50▲42, 63▲, 68▼, 46▲, 78▲, 40▼, 45▲, 55▼, 32▼, 65▼, 70▼, 73▼, 81▼ | W | GC036 |

| Wound | L | F/D | D | Paint the ash | ||||||||||

| Eczema | L | D | D | Powderize then paint together with butter and expose to sunlight | ||||||||||

| 56. | Scrophulariaceae | Verbascum sinaticum Benth. | Kutitina | H | 4 | 0.05 | Stomachache | R | F | O | Peel, chew, and absorb the juice | 31▼, 38▲, 79▼, 59▲, 63▲, 50▼, 78▼, 46▼, 65▼, 45▲, 70▼, 73▼ | W | GC074 |

| Febrile illness | R | F | O | Crush, smash in water, and drink | ||||||||||

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L. | Karia/keto | H | 1 | 0.01 | Malaria | Ft | F | O | Chop the concoction then eat | 72▼, 37▼42, 63▲, 29▲, 46▼, 45▼ | H | GC026 | |

| Datura stramonium L. | Banje | H | 14 | 0.17 | Dandruff | L | F/D | D | Crush the concoction then paint/crush and paint alone | 31▲, 38▲, 79▼, 37▲, 50▼, 59▲, 76▼, 63▲, 61▼, 68▲, 40▲, 77▼, 29▼, 46▼, 45▲, 70▼, 65▼, 78▲, 73▼, 47▼, 83▲, 84▲ | WH | GC124 | ||

| Discopodium penninervium Hochst. | Segelet | S | 2 | 0.02 | Anthrax | L | F | O | Rub and squeeze then drink | 29▲, 65▼ | WH | GC188 | ||

| Stomachache | L | F | O | Squeeze and drink with water | ||||||||||

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | Timatim | H | 1 | 0.01 | Malaria | L | F | O | Squeeze then drink | 38▼, 78▼ | WH | GC207 | ||

| Excessive bleeding after birth | L | F | Vl | Rub and insert in a cloth | ||||||||||

| Nicotiana tabacum L. | Tinbaho | S | 1 | 0.01 | Evil spirit | L | F | N | Rub and insert in the nose | 31▼, 38▼, 50▼, 48▼, 63▼, 68▼, 46▼, 40▼, 45▼, 70▼, 65▼, 83▲ | WH | GC080 | ||

| Solanum incanum L. | Edi | S | 18 | 0.21 | Wound | L | F/D | D | Crush then tie | 31▼, 38▲, 34▼, 50▼, 53▼, 2▼, 76▼, 63▲, 68▲, 40▲, 77▲, 48▲, 29▲, 46▲, 45▼, 55▼, 66▼, 70▼, 73▲, 47▲, 81▲, 83▼ | W | GC059 | ||

| Bleeding | L | F | N | Rub and sniff | ||||||||||

| Bloating | L | F | O | Chop and make Wote then eat with Enjera | ||||||||||

| Swelling | R | F | D | Crush and tie | ||||||||||

| Headache | R | F/D | DNO | Fumigate | ||||||||||

| Scorpion poison | R | F/D | O | Chew and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| Stomachache | R | F | O | Peel, chew, and absorb the juice | ||||||||||

| Solanum marginatum L.f. | Geber enboy | S | 2 | 0.02 | Scorpion poison | R | F | O | Chew and absorb the juice | 38▼, 50▼, 59▼, 46▼, 65▼, 73▼, 81▲ | W | GC095 | ||

| Solanum nigrum L. | Awut | H | 5 | 0.06 | Dactylitis | L | F | D | Rub and tie | 33▲, 49▼, 38▼, 63▲, 67▼, 66▲, 69▲, 71▼, 75▲, 82▲ | W | GC140 | ||

| Wound | L | F/D | D | Crush and tie | ||||||||||

| Herpes zoster | L | F/D | D | Crush the concoction then paint | ||||||||||

| Bleeding | L | F | D | Squeeze and paint | ||||||||||

| Liver problem | L | F | O | Crush and make Wote with butter then eat with Enjera | ||||||||||

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal in DC. | Giziewa/ed ebudha | S | 11 | 0.13 | Evil spirit | L | F/D | DNO | Fumigate | 31▲, 38▲, 79▼, 50▲, 78▲, 3▼, 48▼, 37▲, 76▲, 63▲, 68▲, 77▲, 29▲, 46▼, 45▲, 32▲, 70▼, 65▼, 73▲, 82▲, 83▲, 84▼ | WH | GC048 | ||

| General ailments and epidemic | R and L | F/D | DNO | Rub the leaf then paint/burn the root and fumigate | ||||||||||

| Swelling | R | F/D | D | Crush and mix honey then tie/burn and add honey then paint | ||||||||||

| 57. | Tiliaceae | Grewia ferruginea Hochst. ex A. Rich. | Lenkuata | S | 2 | 0.02 | Asthma and stomachache | R,B | F/D | O | Powder, the concoction then drink with honey and butter | 31▼, 54▼, 40▼, 42▼, 63▼, 77▼46▼, 32▼, 47▼, 83▲ | W | GC123 |

| Grewia kakothamnos K.schum. | Tieka | S | 2 | 0.02 | Swelling | L | F | D | Chew and paint | – | W | GC198 | ||

| 58. | Ulmaceae | Celtis africana Burm.f | – | S | 1 | 0.01 | Dactylitis | L | F/D | D | Crush then tie | 65▼ | W | GC238 |

| 59. | Urticaceae | Urtica simensis Steudel | Sama | H | 3 | 0.04 | Warts | L | F | D | Squeeze then cream and rub on skin | 50▼, 46▼ | W | GC223 |

| 60. | Verbenaceae | Verbena officinalis L. | Atuch | H | 1 | 0.01 | Stomachache | R | F/D | O | Chew and swallow the juice | 31▲, 38▲, 50▼, 59▲, 78▼, 63▼, 29▲, 70▼, 81▼ | WH | GC069 |

| 61. | Vitaceae | Cayratia gracilis (Guill.&Perr.) Suesseng | Aserkush | H | 2 | 0.02 | Herpes zoster | L | F | D | Squeeze the concoction then paint | 63▼ | W | GC222 |

| Cyphostemma cyphopetalum (Fresen.)Desc. Ex Wild & Drumm. | Abawoldu | H | 1 | 0.01 | Eczema | L | F | D | Squeeze the concoction then paint | 64▼, 70▼ | W | GC234 | ||

| Rhoicissus tridentata (L.f)Wild & Drumm. | Este haregawin | Cl | 2 | 0.02 | Brain weakness | R | F/D | O | Powderize the concoction and mix honey then drink the decoction | 38▼, 62▼ | W | GC230 |

Habit: H herb, T tree, S shrub, Cl climber. Pu (plant parts used): L leaf, R root, B bark, Lx latex, Ft fruit, Fr flower, Sd seed, Sb stem bark, Rb root bark. Cp (condition of preparation): F fresh, D dry, F/D fresh or dry. RA route of administration: D dermal, O oral, N nasal; DNO dermal, nasal, and oral; Er ear; Op optical; Vl vaginal. Comparison with similar studies: ▲ similar uses, ▼ dissimilar uses, − no similar documentation found in the reviews. Ht (habitat): W wild, H home garden, WH wild and home garden

Table 4.

Taxonomic diversity of medicinal plant species and their proportions

| Families | No. of genera in each family | No. species in each family and genera | % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asteraceae | 10 | 11 | 8.1 |

| Fabaceae and Lamiaceae | 8 | 9 | 6.6 |

| Solanaceae | 7 | 9 | 6.6 |

| Euphorbiaceae | 5 | 6 | 4.4 |

| Cucurbitaceae | 4 | 4 | 2.9 |

| Rutaceae | 3 | 4 | 2.9 |

| Apiaceae, Acanthaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rubiaceae, and Vitaceae | 3 | 3 | 2.2 |

| Moraceae | 1 | 3 | 2.2 |

| Eight families | 2 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Two families | 1 | 2 | 1.5 |

| 41 families | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

Among the total documented medicinal plant species, Solanum incanum was used to treat the highest number of diseases (Table 5 and Appendix: Table 10). Stomachache (general abdominal problems), wound, febrile illness, swelling, and malaria were the commonly reported diseases, and these were treated with 1.6, 0.13, 0.07, 0.06, and 0.05% medicinal plant species, respectively. People in the study area give first priority for some traditional medicinal plant species to treat ailments than modern drugs. Withania somnifera, Tragia brevipes, Cucumis ficifolius and Zingiber officinale, Ziziphus spina-christi, Salvia merjamie and Salvia nilotica, and Plantago lanceolata and Ruellia patula, are found to be the most important medicinal plant species than the locally available modern drugs to treat swellings, dactylitis, stomachache, dandruff, bleeding, herpes zoster, and occurrence of baldness, respectively. Likewise, healers reported that Thalictrum rhynchocarpum, Ruta chalepensis, and Allium sativum were mixed commonly when they prepared remedy from other traditional medicinal plant species. Besides, among the documented human medicinal plant species, Carissa spinarum, Polygala sphenoptera, Cirsium englerianum, Verbascum sinaiticum, and Achyranthes aspera are also used for the treatment of livestock diseases in Gubalafto District. Likewise, Haplocarpha rueppelii, Urtica simensis, Grewia kakothamnos, Carissa spinarum, Cordia africana, Ficus vasta, and Ziziphus spina-christi are used as food for humans in the wild. The informants in Hara (hot and relatively lowland in the District) also reported that the smashed leaves of Ziziphus spina-christi have been used to prevent the human corpse from rapid deterioration and bad smell until buried.

Table 5.

Individual medicinal plant species used for more number of ailments treatment

| Names of medicinal plant species | No. of ailments treated |

|---|---|

| Solanium incanum | 7 |

| Ruellia patula, Kalanchoe laciniata, and Croton macrostachyus | 6 |

| Solanum nigrum and Achyranthes aspera | 5 |

| Zehneria scabra, Lobelia gibberroa, Phytolacca dodecandra, Rumex nepalensis, Tragia brevipes, and Cucumis ficifolius | 4 |

Of the total collected medicinal plants species, most of them (83) were found from the wild, 20 were obtained from home gardens (those cultivated at home, where they are used also as food or purely for medicinal purposes or both), and 33 species were from both home gardens and wild habitats (Appendix: Table 10). The specific conservation sites for medicinal plant species were not established in the study area; however, the respondents listed the common locations namely Orthodox Church and Muslim Tomb forests, grazing lands, farm lands, riversides, governmental protected forests, and home gardens. Furthermore, the majority of the collected traditional medicinal plant species were herbs with 68 species followed by shrubs (40), trees (20), and climbers (8) (Appendix: Table 10).

Informant consensus factor

Diseases in the study area are grouped into ten ailment categories and informant consensus factor (ICF) analyses were computed. Hence, febrile illness and headache scored the highest ICF value (0.59) followed by dermal diseases (0.52) (Table 6). Febrile illness was also the top recorded health problems in Gubalafto District health office. Headache was treated with Foeniculum vulgare and Solanum incanum, whereas Carduus chamaecephalus, Conyza schimperi, Verbascum sinaiticum, Croton macrostachyus, Cynoglossum coeruleum, Eucalyptus globulus, Geranium arabicum, Lepidium sativum, and Zehneria scabra were used for the treatment of febrile illness (Appendix: Table 10). In addition, Ocimum lamiifolium was used for the treatment of both headache and febrile illness (Appendix: Table 10). Two types of remedies, which were formed from mixtures of two groups of medicinal plant species, were also reported for the treatments of febrile illness. The first group of remedy was prepared from Croton macrostachyus, Cynoglossum coeruleum, Eucalyptus globulus, Lepidium sativum, and Rumex nervosus, and the second remedy was prepared from Achyranthes aspera, Ocimum urticifolium, Bidens pilosa, and Conyza schimperi. Parts of both groups of plant species were burnt, and fumes were inhaled for the treatments of febrile illness (Appendix: Table 10). Dermal diseases had the second ICF value and the highest number of plant species used to treat it (Table 6). The least values of ICF were found in the diseases of excretory and reproductive tracts.

Table 6.

Disease category and their ICF values

| Categories | Ailments/diseases | No. of species used | No. of use citations | ICF values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undefined illness | Febrile and headache | 29 | 70 | 0.59 |

| Dermal | Dandruff, wound, eczema, tinia versicolor, baldness, hemorrhoid, boils/furunclosis, skin cancer, swell | 66 | 135 | 0.52 |

| Respiratory systems | Stomachache, digestion problems, bloat, diarrhea, toothache | 24 | 41 | 0.43 |

| Digestive system | Stomachache, digestion problems, bloat, diarrhea, toothache | 63 | 103 | 0.39 |

| Animal and insect cause | Cutaneous leishmaniasis, snake bite and poison, rabies, malaria, spider poison, scorpion poisons | 26 | 40 | 0.36 |

| Cultural related | Evil eye and evil spirit, diseases epidemic, general illness | 16 | 24 | 0.35 |

| Circulatory systems | Bleeding, hypertension | 16 | 24 | 0.35 |

| Musculoskeletal & nervous system | Bone broke and fracture, nerve problem | 6 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Sense organs | Eye problem, ear mites, ear bloat, trachoma, vision impairment | 17 | 19 | 0.11 |

| Excretory and reproductive | Impotency, urinary retention, expelled uterus, kidney infections, ABO-incompatible, gonorrhea, sexual diseases, retained embryo | 18 | 19 | 0.06 |

Informant consensus

In addition, Ocimum lamiifolium scored the highest number of informant consensus value (30) followed by Eucalyptus globulus, Croton macrostachyus and Cynoglossum coeruleum with 28, 24, and 21 use values, respectively. A leaf of Ocimum lamiifolium is drunk with coffee/tea decoction that treated headache and febrile illness. On the other hand, Eucalyptus globulus was used to treat common cold, appetite reduction, and febrile illness. The total informant consensus values of each medicinal plant species are given in Appendix: Table 10.

Use values

The calculated results of use values (UV) showed that Ocimum lamiifolium scored the highest number, which is 0.36 and Eucalyptus globulus (0.33) scored higher use values than other species. Meanwhile, 40 medicinal plant species scored the least use value, which is 0.01 (Appendix: Table 10).

Fidelity level

The fidelity level (FL) calculation was done for the most cited medicinal plant species with six and above informants. The calculation results showed that all have more than 0.5 values (Table 7). Of the results, Rhamnus prinoides and Datura stramonium scored the highest FL values, 0.97 and 0.86 respectively.

Table 7.

FL values of the 14 most referenced medicinal plants

| Species names | Primary use/s | N | NP | FL | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhamnus prinoides | Tonsillitis | 18 | 17 | 0.94 | 1 |

| Datura stramonium | Dandruff | 14 | 12 | 0.86 | 2 |

| Vicia faba | Boils/furunclosis | 6 | 5 | 0.83 | 3 |

| Cynoglossum coeruleum | Febrile illness | 21 | 17 | 0.81 | 4 |

| Ocimum latifolium | Febrile illness | 30 | 24 | 0.8 | 5 |

| Ruta chalepensis | Stomachache | 14 | 11 | 0.79 | 6 |

| Achyranthes aspera | Tonsillitis, wound, and febrile illness | 19 | 14 | 0.74 | 7 |

| Eucalyptus globules | Febrile illness and common cold | 28 | 19 | 0.68 | 8 |

| Withania somnifera | Febrile illness, evil spirit | 11 | 7 | 0.64 | 9 |

| Rumex nepalensis | Stomachache | 13 | 8 | 0.62 | 10 |

| Solanium incanum | Stomachache | 18 | 10 | 0.56 | 11 |

| Croton macrostachyus | Febrile illness | 24 | 12 | 0.5 | 12 |

| Zehneria scabra | Febrile illness | 18 | 9 | 0.5 | 12 |

| Cucumis ficifolius | Dactylitis | 10 | 5 | 0.5 | 12 |

Preference ranking

Preference ranking values of nine medicinal plant species used to treat bleeding showed that Achyranthes aspera ranked first and followed by Rumex nepalensis (Table 8). Achyranthes aspera was reported to stop abnormal/excessive menstruation and much bleeding during the newborn delivery time. Informants stated that Rumex nepalensis stops bleeding without any patient body contact. The healers cut the leaf and soon they whispered for three times by standing at any distance from the patient by saying “stop the bleeding of the patient blood!” then drop the leaf of Rumex nepalensis to the ground. Immediately, the bleeding stops and the patient recover.

Table 8.

Simple preference ranking values of nine medicinal plants used to stop bleeding in the study area

| Species name | Respondents | Total | Rank | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | R10 | |||

| Achyranthes aspera | 7 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 78 | 1 |

| Clutia lanceolata | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 28 | 8 |

| Salila marjamic | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 40 | 5 |

| Ruellia patula | 4 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 34 | 7 |

| Rumex nervosus | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 37 | 6 |

| Rumex nepalensis | 6 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 75 | 2 |

| Salvia nilotica | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 69 | 3 |

| Solanium incanum | 8 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 62 | 4 |

| Solanum nigrum | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 27 | 9 |

Plant parts used and mode of remedy preparation

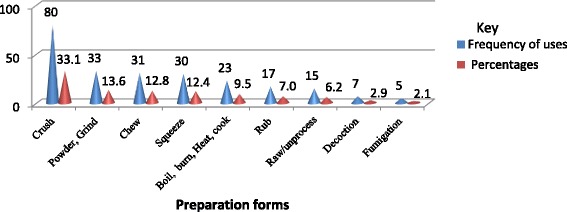

In the study area, eight medicinal plant parts were identified for all documented remedy preparations. Among the total plant parts, 114 traditional plant remedies were prepared from the leaves of 73 medicinal plant species. Likewise, the roots of 51 medicinal plant species were used for the preparations of 76 different remedies (Table 9). Informants applied different traditional medicinal plant remedy in different ways of preparation, of which crushing was reported frequently (Fig. 2 and Appendix: Table 10). In regard to this, most of the medicinal plant remedy preparations involved the use of single plant species or a single plant part. Thus, the mixtures of different medicinal plant species or plant parts are used rarely in the traditional medicinal plant remedy preparations. In addition, the additive substances such as salt, honey, coffee, local beer, milk, butter, and SHIRO (ground legume seeds) were mixed during traditional plant medicine preparations and administrations to extract active components, to prevent the adverse effects of remedies, and to add better tastes and aromas.

Table 9.

Plant parts and their frequency of uses for the preparation of remedies in Gubalafto District

| Plant parts used | Number of reported plant species in each parts | Number of preparations in each parts |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf | 73 | 114 |

| Root | 51 | 76 |

| Seed | 9 | 9 |

| Fruit | 8 | 9 |

| Leaf and root | 8 | 8 |

| Latex | 5 | 8 |

| Bark | 4 | 5 |

| All parts | 5 | 5 |

| Stem and leaf | 2 | 2 |

| Flower, fruit and leaf; fruit, leaf and stem; root and bark | 1 | 1 |

Fig. 2.

Modes of preparation of medicinal plants in Gubalafto District. The number and percentages of preparation forms of traditional plant medicines

Condition of preparations and storage techniques

The fresh and dried materials of traditional medicinal plant remedies were prepared by informants in the study area. The highest (132) number of remedies were prepared from fresh parts of medicinal plants only followed by a fewer number of traditional plant medicines (46) prepared from the dried plant parts only, and 64 remedies were prepared either from dry or fresh plant parts. Healers stored the collected traditional plant medicines in their homes for further usage mostly in powdered and raw dried forms. In this regard, clothes and plastic bags are used mainly to store the dried medicines. However, the preferences of fresh plant parts for medicine are higher than dried once.

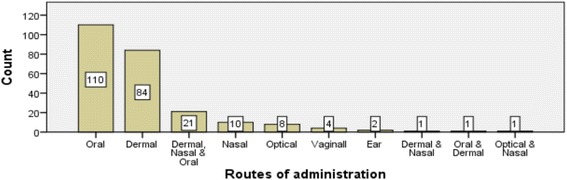

Route of administration, dosage determination, and taboos

The respondent’s reports showed that most of the informants in the study area administered traditional plant medicines through oral and dermal routes (Fig. 3). Coffee cup, tine, finger line, teaspoon, tea glass, the number of powder droplets picked by two finger tips, and palm surface were used for dosage determinations. Medicines prepared from the plant species Justicia schimperiana, Podocarpus falcatus, Acokanthera schimperi, Lobelia gibberoa, Euphorbia abyssinica, Phytolacca dodecandra, and Cucumis ficifolius were reported to be toxic if overdosed. So, the informants reported that the adverse effects of toxic medicinal plant species could be alleviated by taking coffee, local beer, and flax and by eating local food like SHIRO. The healers also made different dosages of traditional medicines based on differences in gender, age, and physical condition and appearance among patients by using their experiences.

Fig. 3.

Routes of administration of traditional plant medicines. Number of traditional medicines and their administration routes reported in Gubalafto District

Furthermore, informants in the study area reported taboos for some medicinal plant species they used. Thus, sexual intercourse was not allowed for healers during traditional medicine preparation and offering for patients. Patients are also not allowed to have sexual intercourse at the time of using Plantago lanceolata medicine to treat Herpes zoster (shingles). At the time of Tragia brevipes prescription for treating “dactylitis”, the patients are prohibited from having sexual intercourse, eating meat, and drinking milk and coffee as well as taking modern drugs. Consequently, informants provided information that the dactylitis patients preferred traditional medicines than modern medicines. Moreover, at the time of menstruation, females are not permitted to take traditional plant medicines, nor are they allowed to touch the prepared traditional medicines for use and contacting patients who took traditional medicines. Hence, patients are kept in their houses separately until they finish the prescribed traditional plant remedies. Informants mentioned about the sources and impacts of taboos that they generated from their ancestors who did these otherwise the disease cannot be cured and the chances for relapsing were said to be high.

Discussion

The most active participants in the study were males that performed their tasks out of their homes. Consequently, they could have chances to learn the useful values of plant species from their daily interactions. In addition, healers preferred males to transfer their indigenous medicinal plant knowledge because of their expectations that a male alone could take the plant species in far sites and forests. Similarly, the dominance of males in studies of traditional medicinal plants was also reported by other researchers [29–34]. In contrast, Friedman et al. [35] mentioned that women know more medicinal plants and these differences may be explained by cultural and occupational disparities. Furthermore, farming was the main task of the people in Gubalafto District that could provide for the higher number of farmers to develop indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants. Meanwhile, the secret transfer systems of indigenous medicinal plant knowledge for one or two individuals in the family members or friends orally at most could facilitate the disappearance of knowledge in the study area in the future. Hence, it should be shared for a considerable number of people in oral and written forms. The secret sharing styles of indigenous knowledge in the community are also performed in other places [2, 29, 30, 36–38]. On the other hand, exchanges of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants among students in religious sites are essential for the dissemination of indigenous plant knowledge in the wider society. There are significant indigenous knowledge variations of healers and general informants showed on the number of medicinal plant species lists and associated uses they mentioned because traditional medicinal practices are the main occupations for healers in the society. In addition, the indigenous knowledge about medicinal plants from both general informants and healers is just a sequestration from generation to generation. However, the absence of significant variations between the young and elder age respondents could be that elders mostly relied on the youth for medicinal plant collections through which the younger generation got chances to know about the medicinal plant identification. This has probably helped to reduce the expected variations in indigenous knowledge on medicinal plant lists and the associated uses asked for during the study. Elders, however, gave in-depth explanations clearly about the uses of medicinal plants including that on dosages and associated histories by using their experiences than the young people.

The reason for finding a large number of documented traditional medicinal plant species and associated uses in Gubalafto District could be related to the diversity of land forms and favorable climatic conditions that the maintained varieties of plant species. Thus, the presence of different plant species in Gubalafto District could be the source of valuable indigenous knowledge used in the community. This could be related to the fact that traditional herbal medicines have helped the people to feel safe with cures indigenous to them that might also be cost-effective [1]. In addition, the preferences of the plant species like Thalictrum rhynchocarpum, Ruta chalepensis, and Allium sativum for the mixtures of remedy preparations with others indicated that these plant species could have high synergy potential because of their medicinal bioactive components. Likewise, the uses of Ziziphus spina-christi for the preservation of human corpse could be the mucilaginous substances of the smashed fresh leaves that would make the skin smooth when painted, which might reduce bacterial and fungal growths. The three documented medicinal plant species, namely, Cirsium englerianumInula confertiflora [23], and Urtica simensis [21] are found in the endemic list of plant species of Ethiopia.

Most of the medicinal plants were more available in the wild areas and have not been cultivated by households in the home gardens. Future efforts need to give due attention to conserve them around human habitations. Flatie et al. [39] reported that some of the medicinal plants were cultivated in home gardens for benefits other than medicine preparation. Hence, the medicinal plants are more exposed to extinction. Unless conserved, the medicinal plants may be highly eroded in the study area in the near future. Hence, the sustainable utilization of medicinal plant species should be practiced through awareness raising and conscious protection in situ and ex situ. In this regard, Balde et al. [34] stated that giving educational training for the people can help the management of traditional medicine easily. Similarly, various studies in Ethiopia [10, 40–47] and other countries [2, 9, 31, 33, 48, 49] reported the necessity of conservation and sustainable utilization of medicinal plant species in the society.

The record of the highest number of herbaceous medicinal plant species in the study could be attributed to the fact that their presence in most parts of the study area is due to the bimodal rainfall and extended availability of moisture in Gubalafto. Similarly, various studies in Ethiopia [29, 31, 39, 42, 44–46, 50] and other countries [9, 33, 51] documented the dominance of herbaceous plant species in traditional medicine preparations. In addition, Hailemariam et al. [52] stated that there were more herbaceous plant species naturally as compared to other plant habits. Works that reported dominance of woody species (shrubs and/or trees) over herbs may have been due to surveys undertaken during the dry season when most annual herbs are absent in the environment.

The presence of a higher number of plant species for traditional medicines from the family Asteraceae could be due to the adaptation potential of the species in the family in a wide range of altitudes in the study area. The evidence given for similar results from Lulekal et al. [40] revealed that the plant families that contributed to the considerably higher number of medicinal plant species were due to their wider distribution and abundance in the flora area as well as the presence of bioactive ingredients. In the same way, other ethnobotanical studies also confirmed the abundance of medicinal plant species in Asteraceae family [31, 35, 41, 49, 53, 54].