Abstract

Introduction:

Insulin resistance (IR) is a known complication of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). It may be an important therapeutic target in stages of chronic kidney disease.

Aim:

The study was conducted to evaluate the effect of short-term treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEpo) therapy on IR, serum leptin, and neuropeptide Y in ESKD patients on hemodialysis.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty ESKD patients were enrolled in the study and were randomly assigned into two groups. Erythropoietin (rHuEpo) group consisted of 15 patients (7 females, 8 males, mean age 47.8 ± 9.3 years) treated with rHuEpo therapy after each session of dialysis. No-rHuEpo group consisted of 15 patients (7 females, 8 males, mean age 45.5 ± 8.6 years) not treated with rHuEpo. In addition to, control group consisted of 15 healthy controls (6 females, 9 males, mean age 48.8 ± 11 years).

Results:

The mean fasting insulin (11 ± 4.2 mU/L) and homeostatic model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) test (2.6 ± 1.1) were significantly higher in ESKD patients than control group (6.6 ± 1.4 mU/L and 1.5 ± 0.3, respectively). There were significant decreases in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (5.6 ± 1%), fasting insulin level (9.3 ± 3.1 μU/mL), HOMA-IR (2.2 ± 0.7), and serum leptin levels (17.4 ± 8.7 ng/mL) also significant increase in neuropeptide Y levels (113 ± 9.9 pg/mL) after 3 months of rHuEpo therapy, in addition to further significantly decrease fasting insulin levels (7.1 ± 2.1 μU/mL) and HOMA-IR (1.7 ± 6) after 6 months in rHuEpo group. In contrast, there were significantly increases in HbA1c% (5.9 ± 0.5%) and leptin levels (42.3 ± 25.3 ng/mL) in No-rHuEpo group throughout the study.

Conclusion:

IR and hyperleptinemia are improved by recombinant human erythropoietin therapy.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, insulin resistance, leptin, neuropeptide Y

INTRODUCTION

Insulin resistance (IR) is a condition, in which a higher than normal insulin concentration is needed to achieve a normal metabolic response.[1] As long as hyperinsulinemia is adequate to overcome IR, glucose tolerance remains normal.[2] Compensatory increases in renal tubular uptake and excretion of insulin in the setting of diminished glomerular filtration rate (GFR) were reported as early as 1970.[3] Numerous factors related to chronic kidney disease (CKD) have been implicated in the etiology of IR. These include uremic toxins, chronic metabolic acidosis, intracellular ion homeostasis disequilibrium, as well as qualitative and quantitative disturbances of insulin receptors on adipocytes, skeletal muscle cells and hepatocytes, cytokines produced by adipocytes (adipocytokines), chronic inflammation as well as low physical activity.[4] DeFronzo et al. demonstrated that resistance to insulin in patients with CKD developed mainly in peripheral tissues. At the same time, no impairment of hepatic glucose uptake or inhibition of glucose synthesis in the liver was observed.[5] Treatment of IR in CKD patients can be achieved by hemodialysis, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, thiazolidinedione, treatment of calcium and phosphate disturbances, and recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEpo).[6]

Nondiabetic patients with an increased serum leptin concentration have been reported to have a higher risk of IR.[7] Leptin seems to play an important role in the regulation of appetite and energy balance in humans[8] Leptin appears to act on the hypothalamus by inhibiting synthesis and release of the neuropeptide Y (NPY). NPY, in contrast to leptin, is one of the most potent appetite stimulants yet demonstrated. Thus, leptin seems to be a powerful regulator of satiety centers of the brain.[9] rHuEpo is now widely used in the treatment of anemia in hemodialyzed patients. Some signs and symptoms found in rHuEpo-treated patients, such as increased libido and potency, improvement of appetite, physical and mental activity, as well as some side-effects of rHuEpo therapy (exacerbation of pre-existing hypertension, seizures, and hyperkalemia) may suggest, that they are caused not only by amelioration of anemia but also by altered function of endocrine organs or by a direct effect of rHuEpo on the nervous system or other organs.[10] Therefore, this present study is conducted to assess the possible effects of short-term treatment with rHuEpo therapy on the IR, plasma leptin, and NPY concentrations in hemodialysis (HD) patients irrespective of diabetic status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This work is a case–control study carried over a period from January 2014 to February 2015. The study included thirty patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) treated by HD at dialysis Department of Tamia Central Hospital. All patients were dialyzed through arteriovenous fistula three times a week for 4 h session using polysulfone high-flux dialyzer 1.6 m2 surface area, with dialysate flow 500 ml/min and dialysate calcium concentration 1.25 mmol/l, using heparin as anticoagulant with tailored doses according to each case and bicarbonate-based dialysate. The adequacy of dialysis was assessed using Kt/V[11] formula (K is patient clearance, t dialysis time, and V urea space).

The patients were divided into two groups. The rHuEpo group comprised 15 patients (7 females, 8 males, mean age 47.8 ± 9.3 years, mean body mass index [BMI] 27.3 ± 3.4 kg/m2, mean duration of HD therapy 83.3 ± 53.7 months) treated with rHuEpo therapy in addition to iron but not receiving blood transfusion; the average EPO dose was 4000–6000/week. The etiology of ESKD in patients of the rHuEpo group was diabetic nephropathy 6, hypertension 4, obstructive nephropathy 3, chronic glomerulonephritis 1, and unknown cause 3 patients. No-rHuEpo group consisted of 15 patients (7 females, 8 males, mean age 45.5 ± 8.6 years, mean BMI 25.6 ± 4.8 kg/m2, mean duration of HD therapy 65 ± 45.3 months) not treated with rHuEpo and had either hemoglobin level >8 g% or refused to take EPO due to financial constraints or those who did not tolerate EPO or had accelerated hypertension secondary to EPO where EPO had to be discontinued, but receiving iron or blood transfusion (when needed) for the management of anemia. The etiology of ESKD in patients of the No-rHuEpo group was hypertension 5, diabetic nephropathy 4, chronic glomerulonephritis 3, and unknown cause 3 patients. Patients were enrolled to the rHuEpo or No-rHuEpo group in a randomized manner. There were no selection criteria that recommended patients to the rHuEpo or No-rHuEpo group. The control group consisted of 15 healthy controls (6 females, 9 males, mean age 48.8 ± 11 years, mean BMI 26.5 ± 3 kg/m2). Blood samples for control group were withdrawn only once.

Inclusion criteria were patients with end-stage renal disease who were receiving regular HD. They included diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The exclusion criteria were diseases affecting fasting insulin levels such as congestive heart failure, patients on corticosteroids, patients on drugs such as beta blockers, biguanides, ACE inhibitors, patients with end-stage pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, liver disease, and cancer. All patients were in stable condition, had no obvious infection, without trauma and surgery. All patients were informed about the content of the study and gave their written approvals before enrollment. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of Al-Azhar University's committee on human experiments.

All patients and controls were subjected to the following: Full medical history and examination. Biochemical evaluations: serum creatinine, blood urea, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglyceride levels, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), fasting blood sugar, and glycated hemoglobin % (HbA1c%). Serum fasting insulin was measured by ELISA Kit (Calbiotech INC., 10461 Austin Dr, Spring Valley, CA, 91978, USA). IR was calculated by homeostatic model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) formula: because of its simplicity, HOMA-IR = Insulin (Mu/mL) × glucose (mmol/L)/22.5. Plasma leptin level was measured using an enzyme Immunoassay method kit (Immunospec Corporation., Suite 103 Canoga Park, CA, 91302, USA). NPY was measured by ELISA Kit (Kamiya Biomedical Co, 12779 Gateway Drive, Seattle, WA 98168, USA). Blood samples for insulin, leptin, and NPY estimation were withdrawn in the morning after overnight fasting immediately before a subsequent hemodialysis session. Blood samples were withdrawn at the beginning and after 3 and 6 months of the study period.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 18.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results were indicated by mean ± standard deviation. Paired-samples t-test was used in comparing the results at baseline, after 3, and 6 months. Independent-samples test was used in comparing independent samples. For qualitative data, the number and percent distribution was calculated, Chi-square was used as test of significance. Significant difference was P < 0.05.

RESULTS

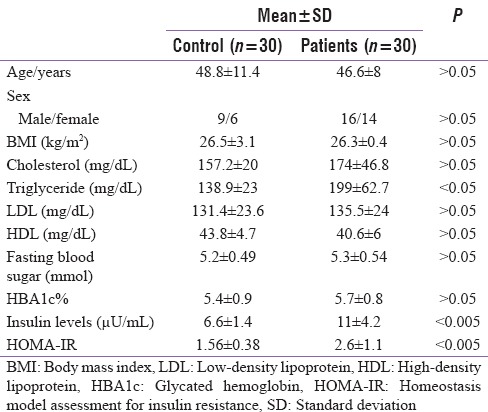

The clinical characteristics of studied groups are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Serum fasting insulin level, HOMA-IR, and serum triglyceride were significantly higher in ESKD patients compared to age, sex, and BMI-matched control individuals [Table 1]. The mean fasting insulin and HOMA-IR levels in ESKD patients were (11 ± 4.2 mU/L and 2.6 ± 1.1), respectively. While, the mean fasting insulin and HOMA-IR levels in control group were 6.6 ± 1.4 mU/L and 1.5 ± 0.3, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison between patients and control groups

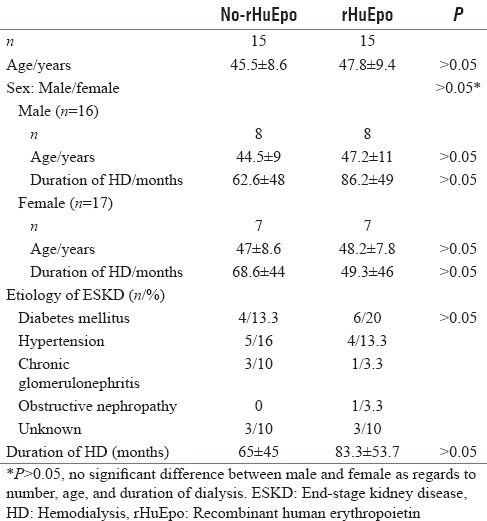

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of recombinant human erythropoietin and no recombinant human erythropoietin groups

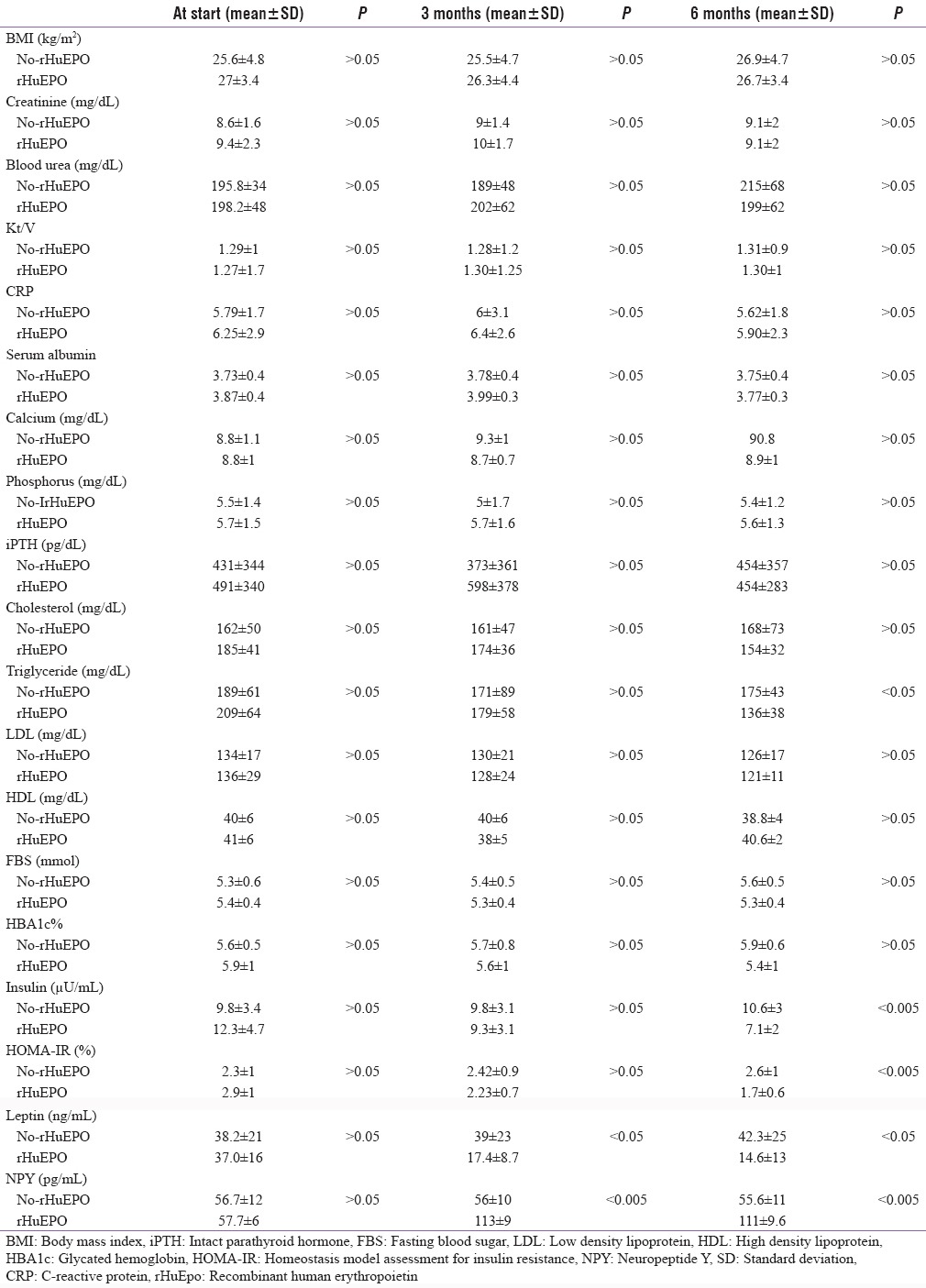

The clinical and baseline biochemical parameters of the rHuEpo and No-rHuEpo groups were a like comparable and are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Their biochemical parameters did not change after 3 months of treatment except for a significant decrease in plasma leptin and significant increase in NPY in rHuEpo group. After 6 months of rHuEpo therapy, a significant decrease in serum triglyceride, fasting insulin level, HOMA-IR level, and leptin levels were noticed, while serum NPY was significantly increased in rHuEpo group [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison between no-recombinant human erythropoietin and recombinant human erythropoietin groups at the start and after treatment

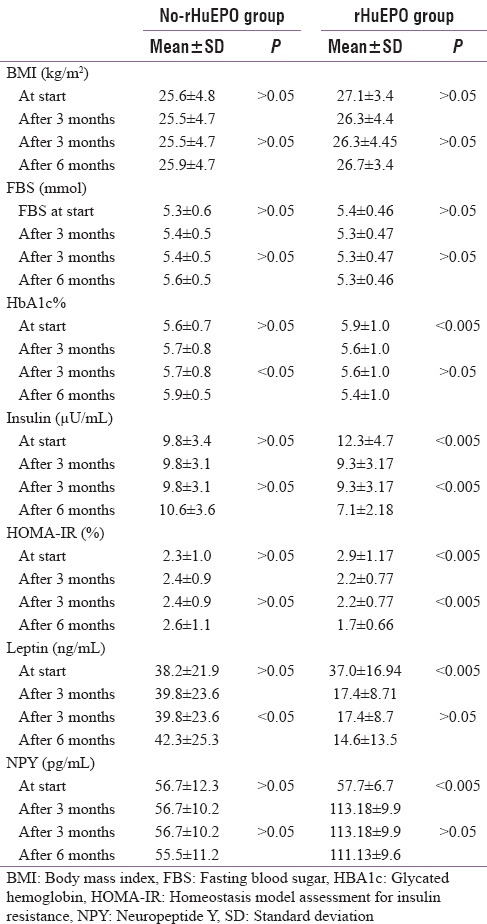

A significant decrease in the mean values of fasting insulin levels as well as IR (calculated by HOMA-IR) was noted in the rHuEpo group after three (9.3 ± 3.17 μU/mL, 2.2 ± 0.77) and 6 months (7.1 ± 2.18 μU/mL, 1.7 ± 0.66%) of rHuEpo therapy as compared to their baseline levels (12.3 ± 4.7 μU/mL, 2.9 ± 1.1%) for insulin levels and HOMA-IR, respectively. Moreover, a significant decrease in the mean values of HbA1c% (5.6 ± 1%) and leptin levels (17.4 ± 8.7 ng/mL) as well as a significant increase in NPY levels (113 ± 9.9 pg/mL); the rHuEpo group was noted after 3 months of rHuEpo therapy as compared to its baseline levels with further insignificant improvement. In contrast to, fasting insulin levels as well as IR (calculated by HOMA-IR) were not significantly different from its baseline levels in No-rHuEpo group throughout the study. Moreover, significant increases in HbA1c% and leptin levels were noted after 6 months of the study as compared to their baseline levels in No-rHuEpo group [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of biochemical parameters during 6 months observation period in each group

The EPO therapy did not influence BMI significantly either in rHuEpo patients or in male and female patients [Tables 2-4]. As regards to serum calcium, serum phosphorus, and PTH did not show significant influence by rHuEpo therapy throughout the study.

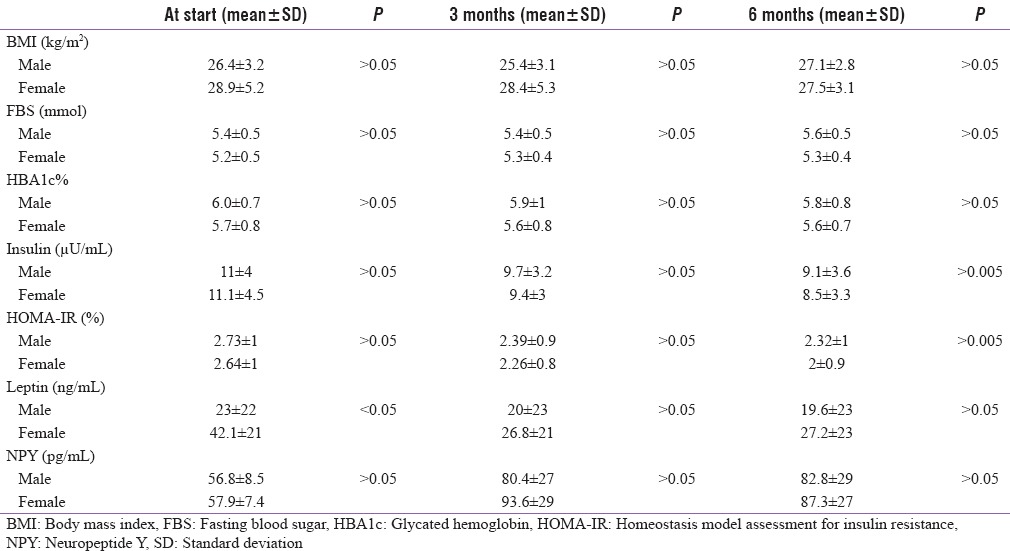

Baseline biochemical parameters of male and female patients were a like comparable except for baseline leptin levels which were significantly higher in female (42.1 ± 21 ng/mL) as compared to male patients (23 ± 22 ng/mL). In spite of the persistent decrease of leptin levels in both sexes after rHuEpo therapy, it is still insignificantly higher in female as compared to male patients [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparison between male and female at every at the start and after treatment

DISCUSSION

Our study confirms the association between ESKD and IR found in the previous studies.[12,13,14] IR has been known to be present even in early stages of CKD.[15] IR, along with oxidative stress and inflammation, is suggested to play a role in the development of albuminuria and declining kidney function.[16,17] IR promotes kidney disease by worsening renal hemodynamics through mechanisms such as activation of the sympathetic nervous system, sodium retention, decreased Na+, K+-ATPase activity, and increased GFR.[17] Like other chronic diseases, patient with ESKD demonstrates low-grade systemic inflammation marked by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), inerleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β.[18] Inflammation and oxidative stress are evident in the early stage of CKD[19] and are also known to induce IR. IR, as potentially modifiable cardiovascular risk factor, is currently considered as a therapeutic target in patients of CKD undergoing HD.

This study showed a significant improvement in fasting insulin levels as well as IR in the HD patients receiving EPO therapy. This has been demonstrated by many previous studies.[2,5,20,21] Improved IR by EPO therapy has been postulated to be due to decreasing Plasma Cell Differentiation Antigen-1 (PC-1) activity which has been found to be elevated in insulin resistant state. PC-1 inhibits insulin signaling either at the level of receptor or downstream at post-receptor site.[22] Improvements in oxygen supplementation and overcoming tissue hypoxia may explain improvement in insulin action.[23] EPO corrects anemia and improves appetite and nutritional status of patients with ESKD, thereby improving IR.[24] Improvement of IR with EPO has also been explained through repair of chronic inflammation, as reduced level of inflammatory cytokines, particularly TNF-α, and iron overload or ferritin level have been found in patients with ESKD on HD.[25] Serum calcium, serum phosphorus, and PTH levels throughout the current study were similar between both groups and did not change by rHuEpo therapy. Therefore, it is unlikely that its play a role in the improvement of IR.

Dyslipidemia is a common disorder in ESkD patients. In CKD patients, total and LDL cholesterol concentrations frequently remain comparable with that of the general population, whereas increases in the triglyceride concentrations and decreases in the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol are often seen. CKD patients had higher prevalence of elevated triglyceride concentration (40% vs. 30% in subjects without CKD) and low HDL cholesterol concentration (43% vs. 29% in subjects without CKD).[26] In this study, the triglyceride concentrations were significantly high in ESKD patients, while the cholesterol levels, LDL and HDL remain comparable with the general population. The significant high level of serum triglycerides had been improved in patients received rHuEpo therapy, and this change was noted after 6 months of treatment, therefore, long-term therapy will explore other beneficial effect of rHuEpo therapy. It has been reported that EPO therapy has a favorable effect on triglyceride and HDL levels in hemodialyzed patients.[2,20]

In the current study and reported by other authors,[27,28] serum leptin levels are elevated in ESKD patients. As serum leptin is cleared by normal kidneys, reduced renal clearance of this hormone may account for elevated serum leptin levels in ESKD patients.[29] Leptin is known to have diverse physiological effects on various organs. It is an important hormone that is related to glucose homeostasis, food ingestion, body weight balance, and hematogenous functions and has an influence on the reproductive and cardiovascular organs.[30] It appears that leptin has an effect on the insulin sensitivity in the peripheral organs. Nondiabetic patients with an increased serum leptin concentration have been reported to have a higher risk of IR.[7,30] Moreover, the serum leptin concentration has a beneficial effect on patients with end-stage renal failure because HD patients with an elevated leptin level become more sensitive to EPO.[31]

In addition, it has been already shown in the previous studies rHuEpo therapy exerts a profound effect on the hormonal status in HD patients by decreasing significantly plasma levels of somatotropin,[32,33,34,35,36] prolactin,[32,33] glucagon, pancreatic polypeptide and gastrin,[35] and increasing plasma concentration of insulin,[35] estradiol,[32] testosterone,[34] atrial natriuretic peptide.[32] In this study, plasma leptin concentrations were significantly suppressed by rHuEpo treatment. This effect of rHuEpo could be due to a direct suppressive effect on leptin synthesis by adipocytes or by an increased leptin turnover.[10] As leptin is presumed to stimulate hemopoiesis, improvement of the hematocrit value induced by rHuEpo therapy could suppress leptin synthesis and release by a feedback mechanism.[36]

It has been reported that ESKD patients show normal[37] or elevated[38,39] NPY plasma levels. In this study, NPY levels were significantly higher in male patients in compared to female patients. The rHuEpo treatment was accompanied by a significant increase of plasma NPY concentration. The pathomechanism of this effect of rHuEpo treatment remains to be elucidated. This fact does not exclude the presence of a suppressive effect of circulating leptin on NPY secretion and receptors at the hypothalamic level, and the existence of a negative feedback between these two hormones in the regulation of food intake and energy expenditure.[9] As demonstrated by Yilmaz et al., basal plasma leptin was high in female patients and still higher in female in compared to male patients throughout this study in spite of significant improving effect of rHuEpo therapy on leptin levels.[40]

CONCLUSION

This research confirmed the association between ESKD and IR, in addition to, a significant improvement in IR as well as hyperlipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia after short-term rHuEpo therapy in hemodialyzed patients. Long-term EPO therapy is advised to explore other beneficial effect of rHuEpo therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell PJ, Mandarino LJ, Gerich JE. Quantification of the relative impairment in actions of insulin on hepatic glucose production and peripheral glucose uptake in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 1988;37:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khedr E, El-Sharkawy M, Abdulwahab S, Eldin EN, Ali M, Youssif A, et al. Effect of recombinant human erythropoietin on insulin resistance in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2009;13:340–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabkin R, Simon NM, Steiner S, Colwell JA. Effect of renal disease on renal uptake and excretion of insulin in man. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:182–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197001222820402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wesolowski P, Saracyn M, Nowak Z, Wankowicz Z. Insulin resistance as a novel therapeutic target in patients with chronic kidney disease treated with dialysis. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010;120:54–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeFronzo RA, Alvestrand A, Smith D, Hendler R, Hendler E, Wahren J. Insulin resistance in uremia. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:563–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI110067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh AK, Mulder J, Palmer BF. Endocrine aspects of kidney disease. In: Brenner BM, Rector T, editors. The Kidney. 8th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Elsevier; 2008. pp. 1749–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zoccali C, Tripepi G, Cambareri F, Catalano F, Finocchiaro P, Cutrupi S, et al. Adipose tissue cytokines, insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and cardiovascular outcomes in end-stage renal disease patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15:125–30. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:292–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalra SP, Kalra PS. Is neuropeptide Y a naturally occurring appetite transducer? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1996;3:57–163. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokot F, Wiecek A, Mesjasz J, Adamczak M, Spiechowicz U. Influence of long-term recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEpo) therapy on plasma leptin and neuropeptide Y concentration in haemodialysed uraemic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1200–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.5.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garred LJ, Barichello DL, DiGiuseppe B, McCready WG, Canaud BC. Simple Kt/V formulas based on urea mass balance theory. ASAIO J. 1994;40:997–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hager SR. Insulin resistance of uremia. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;14:272–6. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(89)80201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fliser D, Pacini G, Engelleiter R, Kautzky-Willer A, Prager R, Franek E, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are already present in patients with incipient renal disease. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1343–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SW, Park GH, Lee SW, Song JH, Hong KC, Kim MJ. Insulin resistance and muscle wasting in non-diabetic end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2554–62. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi S, Maesato K, Moriya H, Ohtake T, Ikeda T. Insulin resistance in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:275–80. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng HT, Huang JW, Chiang CK, Yen CJ, Hung KY, Wu KD. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance as risk factors for development of chronic kidney disease and rapid decline in renal function in elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1268–76. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gluba A, Mikhailidis DP, Lip GY, Hannam S, Rysz J, Banach M. Metabolic syndrome and renal disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;164:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikizler TA. Nutrition, inflammation and chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:162–7. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f5dbce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon V, Rudym D, Chandra P, Miskulin D, Perrone R, Sarnak M. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance in polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:7–13. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04140510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nand N, Jain P, Sharma M. Insulin resistance in patients of end stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Effect of short term erythropoietin therapy. J Bioeng Biomed Sci. 2012;2:114. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy H, Banerjee P, Dan S, Musfikur R, Mohua S, Chiranjeet B. Insulin resistance in end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients in Eastern India: A population based observational study. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2014;4:127–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefanovic V, Djordjevic V, Ivic M, Mitic-Zlatkovic M, Vlahovic P. Lymphocyte PC-1 activity in patients on maintenance haemodialysis treated with human erythropoietin and 1-alpha-D3. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42(Pt 1):55–60. doi: 10.1258/0004563053026790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mak RH. Correction of anemia by erythropoietin reverses insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in uremia. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(5 Pt 2):F839–44. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.5.F839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bárány P, Pettersson E, Ahlberg M, Hultman E, Bergström J. Nutritional assessment in anemic hemodialysis patients treated with recombinant human erythropoietin. Clin Nephrol. 1991;35:270–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasic-Milutinovic Z, Perunicic-Pekovic G, Cavala A, Gluvic Z, Bokan L, Stankovic S. The effect of recombinant human erythropoietin treatment on insulin resistance and inflammatory markers in non-diabetic patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Hippokratia. 2008;12:157–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Levy D, Fox CS. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in chronic kidney disease: Overall burden and rates of treatment and control. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1884–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma K, Considine RV, Michael B, Dunn SR, Weisberg LS, Kurnik BR, et al. Plasma leptin is partly cleared by the kidney and is elevated in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1980–5. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenvinkel P, Heimbürger O, Lönnqvist F. Serum leptin concentrations correlate to plasma insulin concentrations independent of body fat content in chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1321–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.7.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cumin F, Baum HP, Levens N. Leptin is cleared from the circulation primarily by the kidney. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:1120–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Zoccali C. Leptin in end stage renal disease (ESRD): A link between fat mass, bone and the cardiovascular system. J Nephrol. 2005;18:464–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Axelsson J, Qureshi AR, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P, Bárány P. Body fat mass and serum leptin levels influence epoetin sensitivity in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:628–34. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kokot F, Wiecek A, Grzeszczak W, Klepacka J, Klin M, Lao M. Influence of erythropoietin treatment on endocrine abnormalities in haemodialyzed patients. Contrib Nephrol. 1989;76:257–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kokot F, Wiecek A, Klin M. The impact of anaemia in the pathogenesis of endocrine abnormalities in chronic renal failure. In: Hatano M, editor. Nephrology. Vol. 1. Tokyo: Springer Verlag; 1991. pp. 373–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kokot F, Wiecek A, Grzeszczak W, Klin M. Influence of erythropoietin treatment on follitropin and lutropin response to luliberin and plasma testosterone levels in haemodialyzed patients. Nephron. 1990;56:126–9. doi: 10.1159/000186119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kokot F, Nieszporek T, Wiecek A, Marcinkowski W, Rudka R, Trembecki J. Influence of long-term erythropoietin treatment on insulin, glucagon, pancreatic polypeptide, and gastrin secretion in haemodialysed patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(Suppl 3):35–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cioffi JA, Shafer AW, Zupancic TJ, Smith-Gbur J, Mikhail A, Platika D, et al. Novel B219/OB receptor isoforms: Possible role of leptin in hematopoiesis and reproduction. Nat Med. 1996;2:585–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viidas U, Norée LO, Ahlmén J, Theodorsson E, Sylvén C. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure and peptide balance in hemodialysis patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;29:259–63. doi: 10.3109/00365599509180573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hegbrant J, Thysell H, Ekman R. Plasma levels of vasoactive regulatory peptides in patients receiving regular hemodialysis treatment. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1992;26:169–76. doi: 10.1080/00365599.1992.11690449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bald M, Gerigk M, Rascher W. Elevated plasma concentrations of neuropeptide Y in children and adults with chronic and terminal renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:23–7. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yilmaz A, Kayardi M, Icagasioglu S, Candan F, Nur N, Gültekin F. Relationship between serum leptin levels and body composition and markers of malnutrition in nondiabetic patients on peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68:566–70. doi: 10.1016/s1726-4901(09)70095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]