Abstract

Ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), was approved by the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Immune related adverse effects can occur with the use of this agent, but peripheral nervous system problems are rare. We report two cases of ipilimumab-induced polyneuropathy.

Case 1

A 57-year-old man was diagnosed with stage IIIB melanoma at the posterior neck with lymph node involvement. After surgery, he was treated with ipilimumab every 3 weeks under a clinical trial. Day 36 after the treatment started, he developed symmetric painful paresthesias in the soles of his feet which rapidly progressed to the mid-calf. Proprioception was severely impaired which resulted in gait instability. In view of these symptoms, ipilimumab was discontinued after 2 doses. Symptoms did not improve with pregabalin 75 mg BID and a trial of oral prednisone, 120mg per day (1.33 mg/kg dose). He was hospitalized for distal lower extremity weakness with bilateral foot drop. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the brain and spine were normal. Lumbar puncture performed on day 53 revealed 1/mm3 RBC, 78/mm3 WBC with lymphocytic predominance, protein of 68 mg/dL (normal range 21–38 mg/dL) and glucose of 77 mg/dL. Viral PCR for HSV, HHV6, VZV, CMV and EBV, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum paraneoplastic antibody panel and CSF cytology were negative. Nerve conduction study (day 55) revealed symmetric sensorimotor polyneuropathy with markedly decreased CMAP amplitudes and slightly decreased conduction velocities. A trial of methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily for 5 days resulted in a subjective improvement of his sensory symptoms. He was discharged home on a steroid taper. Two weeks later, he received one dose of infliximab 440 mg with no improvement. Infliximab was given extrapolating its use for autoimmune GI processes with the goal of treating his neuropathy. On day 91, he was admitted for fever, truncal rash, and worsening of weakness and paresthesias. Exam revealed significant proximal muscle weakness and more severe distal weakness with minimal movement in both hands and no movement below the ankles. All sensory modalities were severely impaired in the distal limbs. A 5-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was given with no improvement. Repeat nerve conduction study on day 98 revealed markedly decreased amplitude and conduction velocities with conduction block compatible with severe sensorimotor polyneuropathy with demyelinating features. Repeat spinal fluid exam (day 99) was significant for 0/mm3 RBC, 79/mm3 WBC (87% mononuclear cells, 2% neutrophils and 2% eosinophil), protein of 95 mg/dL (normal range 21–38 mg/dL) and glucose of 42 mg/dL. He was immediately treated with tacrolimus 0.3 mg/kg/day divided twice a day, adjusted for an optimal blood level, and methylprednisolone 250 mg every 6 hours for 10 days. A repeat CSF study on day 106 revealed 0 RBC, 8/mm3 WBC, protein of 32 mg/dL (normal range 21–38 mg/dL) and glucose of 133 mg/dL. After symptom stabilization he was discharged to a rehabilitation facility and, at 2 month follow-up, he had some improvement of distal upper extremity strength and was able to walk with a walker. Three years later, he remains with a bilateral foot drop, walks with a cane but was never able to return to full-time work.

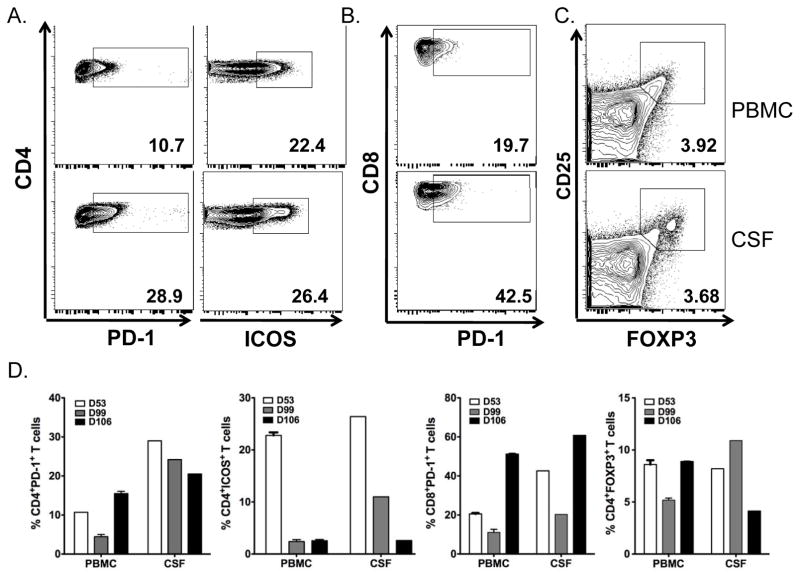

Phenotype staining and Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) multiplex cytokine measurement

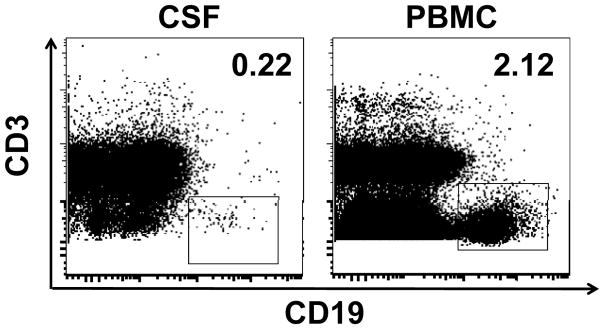

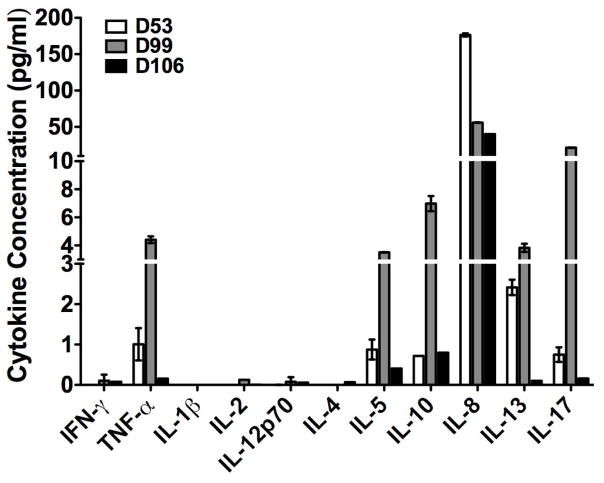

Flow phenotype staining was performed on both peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and CSF which were collected on days 53, 99 and 106. There was no difference in the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells between PBMCs and CSF. The percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells did not change in CSF among three time points. The representative flow plots of CD4+PD-1+, CD4+ICOShi T-cells, CD8+PD-1+ T-cells, CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T-cells from time point day 53 are shown in Figure 1A, 1B and 1C, respectively. The frequency of CD4+ICOShi T-cells in both PBMCs and CSF dramatically decreased from day 53 to 106 (Figure 1D). Interestingly, both CD4+PD-1+ and CD8+PD-1+ T-cells were higher in CSF than PBMCs at day 53. There was a slight decrease of CD4+PD-1+ and CD8+PD-1+ T-cells in CSF. Regulatory T-cells (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+) in the CSF were similar to those in PBMCs. Only 0.22% CD19+ B cells were detected in CSF, one log lower than those in PBMCs (2.12%, Figure 2). We also analyzed the Th1/Th2 and IL-17 cytokine profile. IFN-gamma, IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-12p70 and IL-4 could not be detected. Cytokine profile in CSF revealed the change of TNF-alpha, IL-5, IL-10, IL-8, IL-13 and IL-17 (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Phenotypical changes in CD4+PD-1+, CD4+ICOShi, CD8+PD-1+ T cells, CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells from time point day 53, 99 and 106. Representative dot plots showed CD4+PD-1+, CD4+ICOShi (1A), CD8+PD-1+ T-cells (1B), CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ (1C). 1D. Compilation of data showing the changes during the treatment from day 53 to 106.

Figure 2.

There are very few CD19+ B cells detected in the cerebrospinal fluid. Representative dot plot showed the CD3 and CD19 staining on CSF from day 99.

Figure 3.

Cytokine changes in TNF-alpha, IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13 and IL-17 in case 1 at day 53, 99, 106.

Case 2

A 62-year-old man was diagnosed with stage IIIA melanoma in 2003. After a wide resection with lymph node dissection, he was treated with interferon for 2 months but this was discontinued due to adverse effects. He did well until 7 years after diagnosis when he developed a lung metastasis. Brain MRI done as part of staging was negative. Repeat CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed progression of disease after 2 cycles of interleukin-2 (IL-2) followed by 2 cycles of temozolomide. He received an induction phase of ipilimumab under a clinical trial every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses with an excellent response. One month after completion of the induction phase, he developed painful paresthesias and decreased proprioception below the ankles but preserved strength and reflexes. He reported minor improvement with gabapentin 300mg TID. He received one dose of ipilimumab during the maintenance phase and 1 month later developed fever with jaundice. Liver function tests (LFT) revealed elevated total bilirubin and a transaminitis. Work up for acute viral hepatitis, HIV, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, ceruloplasmin and rheumatologic panels were negative. Percutaneous liver biopsy revealed hepatocellular damage with diffuse histiocytic and lymphocytic infiltration. Tests for mycobacteria, CMV, adenovirus, EBV and iron deposits in the pathology specimen were negative. These findings were thought to be compatible with a drug-related autoimmune hepatitis and therefore ipilimumab was discontinued. He was treated with methylprednisolone and mycophenolate and subsequently had improvement of his LFT with normalization 4 months later. Paresthesias completely resolved within a few months after immunosuppression therapy and he was disease free 2 years after ipilimumab therapy.

Discussion

Ipilimumab has been shown to improve survival of patients with metastatic melanoma in phase III trials1, 2. The mechanism of action involves inhibition of CTLA-4. The CTLA-4 molecule limits the immune response by binding to the antigen presenting cell (APC) receptors with high affinity, thereby blocking the essential co-stimulatory signal and T-cell proliferation. The immune-related adverse events (irAE) commonly involve skin, digestive tract, liver and pituitary gland3. There have been only a few case reports of polyneuropathy associated with ipilimumab. In the first phase III trial by Hodi et al, 1 of 676 patients developed Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS)1. It should be noted that this patient also received GP100 vaccine in the combination arm. There were no reports of neuropathy in the other phase III trial using ipilimumab plus dacarbazine2. One single case report of ipilimumab-induced GBS describes a patient who developed symptoms after the third dose of ipilimumab monotherapy4. Clinical recovery was noted 48 hours after the initiation of high-dose corticosteroids and was nearly complete at 4 weeks. This patient had prior treatment with neurotoxic chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel). The author speculated that this may predispose patients for ipilimumab-related GBS by triggering humoral autoimmunity to ganglioside antigens through mechanisms of antigen retrieval. A recent report found 3 cases of ipilimumab related irAEs with one patient developing chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). Resolution of the neurologic symptoms was seen after discontinuing ipilimumab use and starting immunosuppression.5

Activation of inflammatory cells in the peripheral nervous system and of glial cells in the spinal cord and consequential production of inflammatory cytokines may contribute to pain hypersensitivity6,. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and IL-6 can elicit pain and hyperalgesia6 while cytokine IL-17 is associated with a number of inflammatory diseases. Data from a previous study showed that ipilimumab increases the frequency of CD4+ICOShi T-cells, which comprises an effector T-cell population. Sustained increase in CD4+ICOShi T-cells has been shown to correlate with improved overall survival in metastatic melanoma patients7. CD4+ICOShi T-cells induced by CTLA-4 blockade increased the production of IFN-gamma8. In one study, the co-inhibitory molecule “programmed death” (PD)-1, expressed on activated T-cells, can modify disease severity in a model for an inherited, demyelinating neuropathy9. In Case 1, the frequency of CD4+ICOShi gradually decreased in both blood and CSF. Decrease of CD4+ICOShi cells may down-regulate the cytokine production from these effector cells. CD4+PD-1+ T-cells in CSF were slightly decreased at day 106 while symptoms were stabilized. TNF-alpha was transiently elevated at day 99, but markedly decreased at day 106. Cytokine IL-17, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 had a similar change to TNF-alpha with a peak at day 99, while the patient developed severe worsening of sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Our data indicates a strong relationship between the level of activated effector T-cells with the production of cytokines such as TNFalpha, IL-17 in CSF by ipilimumab and the clinical course of peripheral neuropathy. It is highly suggestive that ipilimumab contributed to our patient’s peripheral neuropathy.

Both of our patients had not had significant treatment with neurotoxic chemotherapy. Infliximab, which blocks the tumor necrosis factor alpha, has been reportedly useful in treatment of immune-related colitis from ipilimumab. However, there has been no report of using infliximab in treating other irAE10. Our first patient represents the severe end of the spectrum of immune-mediated neuropathy. His symptoms were biphasic, progressed over a course of 2 months, and therefore were more compatible with CIDP. The symptoms did not respond to infliximab, high-dose corticosteroids, or IVIG. There was an axonal and demyelinating component with CSF pleocytosis associated with high CSF protein in contrast to albuminocytologic dissociation seen with typical GBS. His symptoms stabilized after treatment with tacrolimus which inhibits T-cell activation. Additionally, the CSF profile normalized after 5 days of treatment indicating a dampened inflammatory process. Case 2 represents the milder end of the spectrum of disease with only sensory involvement and required discontinuation of ipilimumab and treatment with immunosuppression. The time-course relationship with ipilimumab and the coexistent autoimmune hepatitis support the role of underlying immune-mediated mechanism.

Acknowledgments

Funding: No funding was provided

The authors would like to thank Drs. Jianda Yuan and Zhenyu Mu from the Immune Monitoring Core Facility, Sloan Kettering Institute, for their help with phenotype staining and cytokine measurement.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Thaipisuttikul has no conflict of interest

Dr. Chapman has no conflict of interest

Dr. Avila has no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaehler KC, Piel S, Livingstone E, et al. Update on immunologic therapy with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in melanoma: identification of clinical and biological response patterns, immune-related adverse events, and their management. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:485–498. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilgenhof S, Neyns B. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody-induced Guillain-Barre syndrome in a melanoma patient. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:991–993. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao B, Shroff S, Kamiya-Matsuoka C, et al. Atypical neurological complications of ipilimumab therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:589–593. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommer C, Kress M. Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carthon BC, Wolchok JD, Yuan J, et al. Preoperative CTLA-4 blockade: tolerability and immune monitoring in the setting of a presurgical clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2861–2871. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liakou CI, Kamat A, Tang DN, et al. CTLA-4 blockade increases IFNgamma-producing CD4+ICOShi cells to shift the ratio of effector to regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14987–14992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806075105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroner A, Schwab N, Ip CW, et al. The co-inhibitory molecule PD-1 modulates disease severity in a model for an inherited, demyelinating neuropathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minor DR, Chin K, Kashani-Sabet M. Infliximab in the treatment of anti-CTLA4 antibody (ipilimumab) induced immune-related colitis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24:321–325. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]