Abstract

Globally, women bear an uneven burden for sexual HIV acquisition. Results from two clinical trials evaluating intravaginal rings (IVRs) delivering the antiretroviral agent dapivirine have shown that protection from HIV infection can be achieved with this modality, but high adherence is essential. Multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs) can potentially increase product adherence by offering protection against multiple vaginally transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy. Here we describe a coitally independent, long-acting pod-IVR MPT that could potentially prevent HIV and HSV infection as well as unintended pregnancy. The pharmacokinetics of MPT pod-IVRs delivering tenofovir alafenamide hemifumarate (TAF2) to prevent HIV, acyclovir (ACV) to prevent HSV, and etonogestrel (ENG) in combination with ethinyl estradiol (EE), FDA-approved hormonal contraceptives, were evaluated in pigtailed macaques (N = 6) over 35 days. Pod IVRs were exchanged at 14 days with the only modification being lower ENG release rates in the second IVR. Plasma progesterone was monitored weekly to determine the effect of ENG/EE on menstrual cycle. The mean in vivo release rates (mg d-1) for the two formulations over 30 days ranged as follows: TAF2 0.35–0.40; ACV 0.56–0.70; EE 0.03–0.08; ENG (high releasing) 0.63; and ENG (low releasing) 0.05. Mean peak progesterone levels were 4.4 ± 1.8 ng mL-1 prior to IVR insertion and 0.075 ± 0.064 ng mL-1 for 5 weeks after insertion, suggesting that systemic EE/ENG levels were sufficient to suppress menstruation. The TAF2 and ACV release rates and resulting vaginal tissue drug concentrations (medians: TFV, 2.4 ng mg-1; ACV, 0.2 ng mg-1) may be sufficient to protect against HIV and HSV infection, respectively. This proof of principle study demonstrates that MPT-pod IVRs could serve as a potent biomedical prevention tool to protect women’s sexual and reproductive health and may increase adherence to HIV PrEP even among younger high-risk populations.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and unintended pregnancy represent a major global burden for women particularly in resource-limited regions.

The global response to the HIV epidemic has resulted in the number of new infections being halved in 2012 since the peak in 1996 [1], largely resulting from scale-up of prevention and treatment efforts. In Fast-Track, the UNAIDS has set the aggressive target of 500,000, or fewer, new annual infections by 2020, a 75% reduction from 2010 numbers, and ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 [2]. However, recent statistics suggest that a prevention gap has been reached, with the number of annual, new HIV infections stalling around 1.9 million since 2010 [3]. To meet the ambitious UNAIDS Fast-Track goals, highly effective biomedical prevention modalities for HIV prevention will be required.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), the serotype most commonly associated with genital herpes, and HIV form the basis for two intersecting epidemics, where morbidity from one virus facilitates the transmission and pathogenesis by the other [4–7]. A systematic meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found HSV-2 incidence to be associated with a two- to five-fold increased risk of HIV acquisition among both men and women [8, 9]. Seroprevalence rates of HSV-2 are highest in developing countries, in particular throughout Africa and the Americas [10], and can range from 60% to 80% in young adults [11]. Infection by HSV-2 can lead to inflammation of the vaginal mucosa, increasing susceptibility to HIV infection and virus replication at the point of entry and potentially reducing topical PrEP effectiveness [12]. Consequently, interventions against HSV-2 may have a key role in HIV prevention initiatives [13].

There is accumulating clinical trial evidence suggesting that oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens based on the prodrug tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) can be effective at preventing HIV transmission [14–20], but low adherence to product use also has contributed to a number of negative trial results [21]. Adherence to therapy is known to be inversely related to dosing period [22–25]. The compliance burden associated with frequent dosing can be reduced with long-acting drug formulations, such as intravaginal rings (IVRs) [26] as well as implantable and injectable formulations [27]. In addition, multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs) represent an integrated biomedical approach aimed at providing dual protection [28–30], usually from HIV infection and unintended pregnancy. The MPT strategy exploits synergies in demand for protection [31], significantly increasing the likelihood of increased uptake relative to single-purpose products [32].

Two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (MTN-020–ASPIRE and IPM 027–The Ring Study) recently evaluated a monthly IVR delivering the non-nucleoside HIV reverse-transcriptase inhibitor dapivirine. The trials enrolled 2,629 and 1,959 women, respectively, between the ages of 18 and 45 years in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe and demonstrated that an IVR delivering an ARV agent can reduce the risk of HIV acquisition by as much as 56% in highly adherent users. However, it also showed that certain subgroups, particularly young women between 18–21 years of age, did not adhere to IVR use and, consequently, were not protected from HIV infection [33]. An MPT IVR against HIV, HSV, and unintended pregnancy may help overcome adherence issues.

The primary purpose of this proof-of-concept study was to describe an innovative, triple-purpose MPT IVR (termed “pod-IVR”) delivering the ARV drug tenofovir alafenamide hemifumarate (TAF2) in combination with the antiherpetic drug acyclovir (ACV) and etonogestrel (ENG)-ethinyl estradiol (EE), an established progestin-estrogen combination for contraception. The pharmacokinetics of the MPT IVR were evaluated in pigtailed macaques and demonstrated that all four agents could be delivered at independently controlled release rates to provide vaginal mucosal, tissue, and systemic drug concentrations required for therapeutic efficacy.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tenofovir alafenamide hemifumarate (TAF2) [34] was kindly provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, CA) under a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) dated 11/08/13. The remaining active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients were purchased from commercial sources. Stable isotope labeled standards were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals, Inc. (Brea, CA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) with a mean molecular weight (Mw) 85,000–124,000 kD (98–99% hydrolyzed) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted.

Fabrication of combination pod-intravaginal rings

Macaque-sized [35] polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, silicone) pod-IVRs were prepared in a multi-step process that has been described in detail elsewhere [36–39]. Two configurations of pod-IVRs were manufactured, as summarized in Table 1, where Configuration A was designed for rapid ENG release and Configuration B was designed for slow ENG release.

Table 1. Drug loading in pod-IVRs used in pigtailed macaque studies.

| IVR API loading (mg)a,b | ||

|---|---|---|

| API | Configuration Ac | Configuration Bd |

| TAF2 | 45.0 ± 1.8 | 43.9 ± 1.4 |

| ACV | 44.2 ± 2.2 | 46.0 ± 1.5 |

| ENG | 22.0 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 0.2 |

| EE | 11.1 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.2 |

arepresents total drug loading in IVR

bmean ± SD

crapid-releasing ENG

dslow-releasing ENG

In vitro studies

All in vitro release studies were designed to mimic sink conditions using methods reported previously [36]. Briefly, the IVRs were placed in a simplified vaginal fluid simulant (VFS) [40] dissolution media (100 mL) consisting of 25 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.2) with NaCl added to achieve 220 mOs. The vessels were agitated in an orbital shaker at 37 ± 2°C and 60 rpm. In some cases, the media was replaced daily. Aliquots (100 μL) were removed at predetermined timepoints and were replaced with an equal volume of dissolution media. Samples were stored at -20°C prior to analysis.

The concentration of TAF2, its hydrolysis product tenofovir (TFV) and metabolite Met Y [41, 42], ACV, ENG, and EE was measured by HPLC with UV detection (1100 Series, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For measurement of residual TAF2, as well as TFV and Met Y, ACV, ENG, and EE in used IVRs, the mobile phase was composed of A: 1% acetic acid + 3% acetonitrile in water and B: acetonitrile. The gradient program was 0% B (2 min); 0–25% B (2 min); 25% B (1 min); 25–50% B (3 min); and 50% B (6 min) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min-1. A Waters (Milford, MA) Atlantis T3 C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm; 5 μm; 100A) was used as the stationary phase. The retention times were: TAF2, 7.71 min; Met Y, 5.86 min; TFV, 1.08 min.; ACV, 1.29 min; EE, 10.82 min; ENG, 11.99 min. For in vitro release studies, TAF2, TFV, and ACV were measured using the same method. For in vitro release studies of ENG and EE, the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile:water in the ratio of 50:50 (vol/vol), and a Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) Kinetex XB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm; 2.6 μm; 100A) was used as the stationary phase. The retention times were: EE, 2.37 min; ENG, 4.04 min. For all methods, detection wavelengths were 260 nm (TAF2, Met Y, TFV, and ACV), 240 nm (ENG), and 280 nm (EE).

Nonhuman primate studies

Ethics statement

All pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) used in this study were housed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, GA), and the work was performed as described in the animal use research protocol (2445SMIMONC) approved by the CDC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The facility is AAALAC accredited (AAALAC #00052 and PHS assurance #A4365-01) and animal husbandry and enrichment is performed by the Comparative Medicine Branch (CMB) under the direct supervision of the attending veterinarians and the animal enrichment coordinator. All efforts are made to pair house compatible animals by species and gender whenever possible. Cage sizes comply with the Animal Welfare Act and as outlined in the CMB Environmental Enhancement plan (dimensions: 30” wide × 30” deep × 30” tall). Macaques were monitored twice daily for physical and behavioral health by trained CMB staff and undergo quarterly physical examinations. Animals were routinely screened for enteric pathogens, and monitored for weight loss and behavioral abnormalities (lethargy, loss of appetite, self-mutilation). All treatments are at the discretion of the attending veterinarians and trained CMB staff. The investigator is consulted if a condition cannot be managed medically and if so, animals are humanely euthanized to prevent further trauma in accordance with the 2000 Report of the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia (http://www.avma.org/issues/animalwelfare/euthanasia.pdf). Standard enrichment for nonhuman primates includes access to objects to manipulate in the cage, swings or perches, a variety of food supplements such as fresh fruits, seeds, and vegetables, foraging and/or task-oriented feeding methods, and interaction with animal caretakers.

All animals in this study were previously enrolled in CDC IACUC approved efficacy studies and were infected with SHIV162P3 and subsequently released to protocol 2445SMIMONC and scheduled for euthanasia. The animals used in this study were only available for a short time. For terminal PK studies we only use SHIV-infected animals slated for necropsy. Sacrificing healthy uninfected animals for terminal PK studies is not approved under the CDC IACUC protocol that was used for this study, especially given the high cost and restricted availability of female pigtailed macaques. At the end of this study all macaques were euthanized (intravenous pentobarbital) in accordance with the 2000 Report of the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia (http://www.avma.org/issues/animalwelfare/euthanasia.pdf).

Pharmacokinetic study

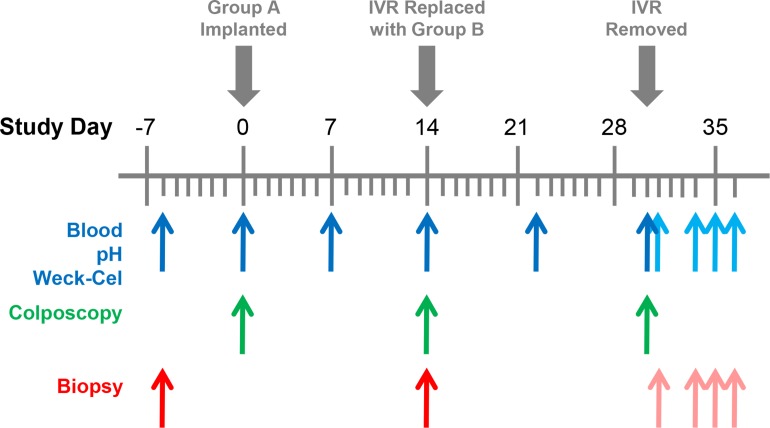

The pharmacokinetic (PK) study was carried out at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under approved CDC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol 2445SMIMONC, and standard guidelines according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (DHEW No. NIH 86–23). The study timeline and biological sample collection points are shown in Fig 1 and employed published protocols [39, 43]. Briefly, six sexually mature female pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) were used in the study. Configuration A pod-IVRs (rapid-releasing ENG) were inserted on Day 0 into the posterior vagina and were replaced on Day 14 with Configuration B pod-IVRs (slow-releasing ENG) and remained in place for another 16 days. The two configurations were designed to test fast- and slow-releasing formulations of ENG sequentially.

Fig 1. Pigtailed macaque TAF2-ACV-ENG-EE pod-IVR study timelines and biological sample collection points (N = 6).

Configuration A pod-IVRs (rapid-releasing ENG) were inserted on Day 0 and replaced on Day 14 with Configuration B pod-IVRs (slow-releasing ENG). The Configuration B IVRs were removed on Day 30 and animals were euthanized on Day 34 (animal ID BB495 and DC42), Day 35 (animal ID PHz1 and PPk2), and Day 36 (animal ID PEc2 and BB0539). Blue arrows, in order of collection, blood, pH, and vaginal fluid (two Weck-Cel samples per time point—two proximal and two distal to the IVR). Green arrows, colposcopy examination (right after blood collection). Red arrows, vaginal tissues (six pinch biopsies per time point—three proximal and three distal to the IVR). Complete vaginal tracks were collected at necropsy. Pale blue and pale red arrows correspond to sample collection points with the IVR removed.

Animals were humanely euthanized using techniques recommended by the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines on Euthanasia, 2013, and in accordance with CDC-Atlanta IACUC Policy 016 on Euthanasia. Necropsies were performed in groups of two on Days 34, 35, and 36. At necropsy, the complete vaginal tracts (ca. 4 × 6 cm) were collected and sectioned into uniform 5 × 7 grids (cervix to introitus in the smaller dimension) and the sections (ca. 8 mm in dia. or square) preserved for analysis. Multiple sections (ca. 12–15) were combined for CD4+ and CD4- cell isolation using published methods [44, 45]. CD4+ and CD4- cells were isolated from inguinal and iliac lymph node tissues using analogous methods.

Safety measures

Rudimentary product safety was evaluated by clinical observations, cage-side observations (twice daily), and vaginal pH.

In vivo pod-IVR drug release rates

Used IVRs were analyzed for residual drug content using published methods [39]. The HPLC methods were the same as those used to analyze aliquots from the in vitro studies.

Bioanalysis of in vivo samples

Concentrations of TAF2, TFV, ACV, ENG, and EE in vaginal fluids, vaginal tissue homogenates, cellular lysates (CD4+ and CD4- cells isolated from vaginal and lymph node tissues), and plasma were measured by LC-MS/MS using published methods [45, 46] and the methods described below. The analyses were performed at the following institutions: TFV and TFV-DP, Johns Hopkins University; ACV, ENG, and EE in cervicovaginal fluid (CVF), Oak Crest Institute; and EE in plasma, Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. The analytical ranges in the above sample matrices are presented in Table 2. Progesterone plasma concentrations were analyzed by the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center using a published method [47]. All new bioanalysis methods are described in detail in the Supporting Information (S1 File).

Table 2. Analytical ranges for biological samples.

| Sample matrix (units) | TAFa | TFV | TFV-DPb | ACV | ENG | EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal fluid (ng sample-1) |

10–10,000 | 10–5,000 | NAd | 100–10,000 | 5–1,025 | 0.05–3c |

| Vaginal tissue, homogenate (ng sample-1) |

NAd | 0.05–50 | 50–1,500 | 1–5,000 | NAd | NAd |

| Vaginal tissue, intracellular (ng sample-1) |

NAd | NAd | 50–1,500 | NAd | NAd | NAd |

| Plasma (ng mL-1) |

NAd | 0.31–1,000 | NAd | 1–50 | 0.25–5.0 | 0.019–0.6 |

The low number in the range represents the analytical lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ).

aanalyzed as the free-base (TAF), not the hemifumarate salt (TAF2)

bfmol sample-1

cmeasured by ELISA

dNA, not applicable

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameter values were determined by noncompartmental analysis (NCA) using Phoenix WinNonlin 6.4 (Pharsight Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). The NCA was run using the linear trapezoidal rule for increasing concentration data and the logarithmic trapezoidal rule for decreasing concentration data (linear up and log down) as the calculation method, and concentration values below the corresponding LLOQs (CLLQ) were treated as:

| (1) |

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.00, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Unpaired comparisons were tested using one-way ANOVA for three or more groups and unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction for two groups. We tested for paired differences among conditions using the Friedman test with Dunn’s post test for multiple comparisons as well as Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test where appropriate. The statistical hypothesis test used to compare each dataset is specified below. Statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05.

Results

In vitro studies

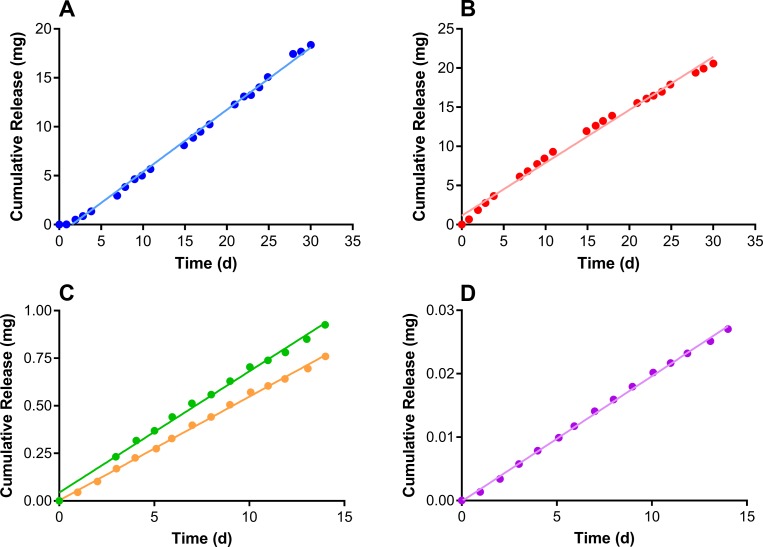

In vitro cumulative release profiles for the Configuration A and Configuration B IVR formulations (Fig 2) exhibited linear, sustained drug release (TAF2, R2 = 0.997; ACV, R2 = 0.991; ENG-A, R2 = 0.994; ENG-B, R2 = 0.998; EE, R2 = 0.999), as is typical for pod-IVRs [26, 36, 37, 39, 43, 48, 49]. The daily release rates obtained from the slopes of the cumulative release profiles are presented in Table 3. The in vitro release rates for highly water-insoluble compounds, such as ENG and EE, often are not predictive of in vivo release rates, as seen here. Previous pod-IVR studies have shown that while in vitro studies are useful for product quality control, in vitro-in vivo correlations (IVIVCs) of unity are not usually observed [39, 49].

Fig 2. TAF2-ACV-ENG-EE pod-IVR in vitro release kinetics.

Circles correspond to means (N = 4–6) and lines correspond to linear regressions. (A) TAF2. (B) ACV. (C) ENG: green, pod-IVR Configuration A; orange, pod-IVR Configuration B. (D) EE.

Table 3. In vitro and in vivo daily release rates from Configuration A and Configuration B MPT pod-IVRs.

| Drug |

In vitro release rate (mg day-1)b |

In vivo release rate (mg day-1)b |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration Aa | ||

| TAF2 | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.07 |

| ACV | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 0.70 ± 0.10 |

| ENG | 0.063 ± 0.8×10−3 | 0.63 ± 0.14 |

| EE | 2.0×10−3 ± 0.03×10−3 | 0.033 ± 0.021 |

| Configuration Ba | ||

| TAF2 | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.08 |

| ACV | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.09 |

| ENG | 0.055 ± 0.8×10−3 | 0.053 ± 0.014 |

| EE | 2.0×10−3 ± 0.03×10−3 | 0.078 ± 0.008 |

a N = 6

b mean ± SD

In vivo drug release rates

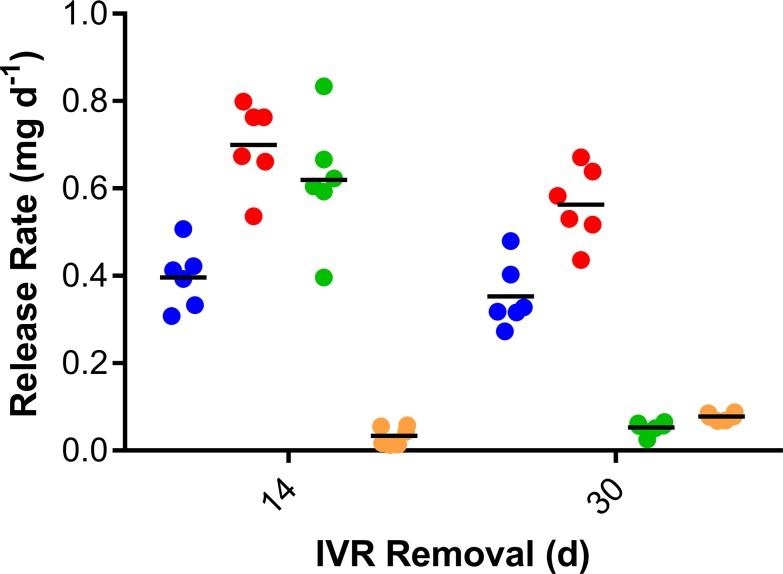

The mean daily in vivo drug release rates for Configuration A (removed on Day 14) and Configuration B (removed on Day 30) pod-IVRs are provided in Table 3 and Fig 3. Release rates are based on the residual drug mass remaining in the used IVRs and the assumption, supported by in vitro data (Fig 2) that drug release is linear over the period of IVR use. Importantly, >95% of the residual TAF2 in the used IVR pods was present as the prodrug by HPLC; i.e., no significant prodrug hydrolysis was observed following two weeks of use in vivo. The Configuration A and Configuration B drug in vivo release rates (with the exception of ENG) were compared using an unpaired t test with Welch’s correction: TAF2, not significantly different (P = 0.3316); ACV, significantly different (P = 0.0276); and EE, significantly different (P = 0.0002).

Fig 3. TAF2-ACV-ENG-EE pod-IVR in vivo daily drug release rates based on residual drug measurements on used IVRs.

Blue circles, TAF2; red circles, ACV; green circles, ENG; orange circles, EE. Horizontal lines represent means.

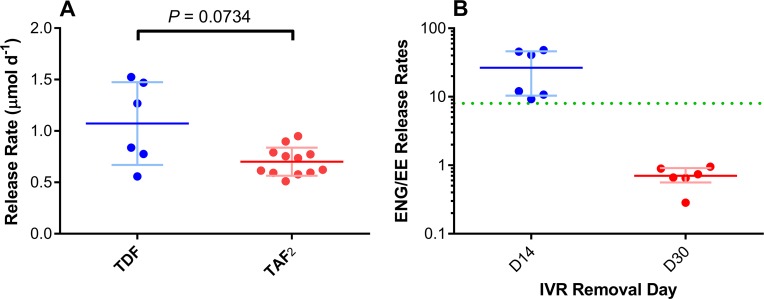

The TAF2 in vivo molar release rates were not significantly different (P = 0.0734) from TDF release rates, also in pigtailed macaques, from a previous study using TDF-FTC pod-IVRs [39] (Fig 4A) allowing meaningful comparison of PK parameters for both TFV prodrugs. The median molar TAF2 release rate was 64% of the median TDF release rate in these studies. An important advantage of the pod-IVR is that drugs are physically isolated from one another and each pod releases its payload at an independently controlled rate [36], making the comparison possible across studies.

Fig 4. In vivo IVR drug release rates in the context of previous studies.

(A) Molar daily in vivo release of TDF from a previous pod-IVR study in pigtailed macaques [39] compared to TAF2 release rate in the present study. An unpaired t test with Welch’s correction shows that while the release rates are not statistically significantly different (P = 0.0734), they are similar, with the mean TAF2 release rate (red horizontal bar) being lower than the mean TDF release rate (blue horizontal bar) from the TDF-FTC pod-IVRs. Each circle corresponds to an individual datum; pale error bars correspond to standard deviations from the mean. (B) Paired ENG:EE in vivo release rate ratios for Configuration A (blue) and Configuration B (red) pod-IVRs. The ratios span the in vivo ENG:EE release rate ratio for the NuvaRing® in women (green broken horizontal line). Each circle corresponds to an individual datum; horizontal lines, means; pale error bars, standard deviations from the mean.

The high (Configuration A) and low (Configuration B) ENG in vivo release rates and the consistently low EE release rates allowed a wide range of in vivo ENG:EE release rate ratios to be attained (Fig 4B). These ratios bracket the corresponding value (in vivo ENG:EE release rate ratio = 8) from the NuvaRing® in women, as shown in Fig 4B by the green broken line.

Safety measures

All IVRs were retained and there were no observations of abnormal behavior, loss of appetite, or unusual stool over the course of the study. Vaginal pH was measured prior to IVR insertion, during IVR use, and following IVR removal (Fig 1). The pH differences with the IVR in place and post removal were found to be insignificant from the baseline using a Friedman test with Dunn’s post-test for multiple comparisons (Day -6) and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (Day 0). The median vaginal pH prior to IVR insertion and with the IVR in place was 8.50 (IQR, 8.20–8.85) and 8.50 (IQR, 8.50–8.70), respectively.

Summary of drug concentration measurements

Drug and drug metabolite concentrations in key anatomic compartments are summarized in Table 4. Vaginal tissue drug samples were not collected with Configuration B pod-IVRs in place, but were collected on Day 31, one day after IVR removal, to analyze drug washout.

Table 4. Summary of drug and drug metabolite concentrations at all sampled anatomic sites (six animals).

| Analyte, matrix, unitsa | Nb | % > LLOQc | Proximald,e | Distald,e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration A | ||||

| TAF,f vaginal fluid, ng mg-1 | 24 | 12.5% | 1.9 (NA) | 0.5 (NA) |

| TFV, vaginal fluid, ng mg-1 | 24 | 100% | 13.3 (4.2–17.4) | 4.4 (1.9–7.1) |

| ACV, vaginal fluid, ng mg-1 | 24 | 100% | 25.8 (10.3–46.2) | 11.7 (3.6–21.0) |

| TFV, vaginal tissue, ng mg-1 | 6 | 100% | NAg | 2.4 (1.2–7.8) |

| TFV-DP, vaginal tissue, fmol mg-1 | 6 | 83.3% | NAg | 20.2 (12.6–97.2) |

| ACV, vaginal tissue, ng mg-1 | 18 | 100% | NAg | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) |

| TFV, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 91.7% | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | NAg |

| ACV, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 91.7% | 3.98 (3.19–4.25) | NAg |

| ENG, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 100% | 2.00 (1.46–2.29) | NAg |

| EE, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 100% | 0.10 (0.06–0.27) | NAg |

| Configuration Bh | ||||

| TAF,f vaginal fluid, ng mg-1 | 24 | 29.2% | 0.2 (0.1–7.5) | 0.75 (0.6–0.8) |

| TFV, vaginal fluid, ng mg-1 | 24 | 100% | 5.7 (3. 8–9. 7) | 3.9 (2.5–5.6) |

| ACV, vaginal fluid, ng mg-1 | 24 | 91.7% | 28.7 (20.4–39.2) | 20.0 (12.5–26.1) |

| TFV, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 100% | 0.6 (0.5–1.0) | NAg |

| ACV, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 91.7% | 3.31 (2.28–4.63) | NAg |

| ENG, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 41.7% | 0.42 (0.40–0.47) | NAg |

| EE, plasma, ng mL-1 | 12 | 100% | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | NAg |

aIncludes all values for timepoints with IVR in place

bNumber of samples analyzed

cProportion of samples that contained quantifiable drug levels

dMedian (interquartile range, 25th - 75th)

eRelative to IVR

fanalyzed as the free-base, not the hemifumarate salt (TAF2)

gNA, not applicable

hUnpaired t tests with Welch’s correction were used to compare CVF antiviral drug concentrations obtained with Configuration A versus Configuration B IVRs and found no statistically significant difference between these datasets in both proximal and distal sampling locations. The corresponding P-values are presented in the Results section.

Cervicovaginal fluid drug levels

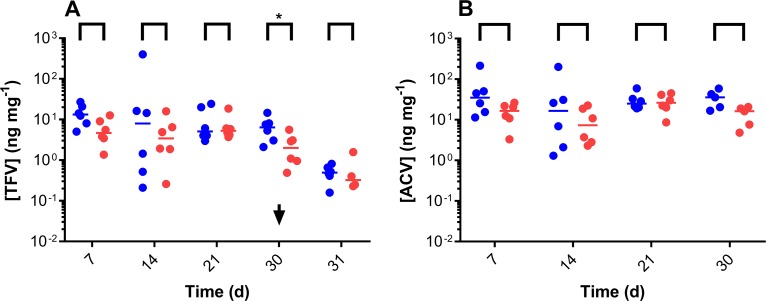

Steady state concentrations of TFV (Fig 5A), the hydrolysis product of the prodrug TAF2, and ACV (Fig 5B) proximal to the pod-IVRs as a function of time were maintained in cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) over the 30 days of IVR use (one-way ANOVA; TFV, P = 0.4660; ACV, P = 0.8090). The concentrations of Met X and Y [41, 42] were below the LLOQ of the assay in these samples. Paired CVF TFV and ACV concentrations proximal and distal to the IVRs were not statistically different (Fig 5), with the exception of TFV on Day 30 (P = 0.0313). Unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction were used to compare CVF antiviral drug levels in Configuration A versus Configuration B: TFV, proximal, P = 0.3074; TFV, distal, P = 0.6669; ACV, proximal, P = 0.3751; ACV, distal, P = 0.0900. There was no significant difference between these paired datasets.

Fig 5. In vivo (N = 6) vaginal fluid drug levels from Configuration A (Day 7, Day 14) and Configuration B (Day 21, Day 30) TAF2-ACV-ENG-EE pod-IVRs.

Blue, proximal to the IVR; red, distal to the IVR; each circle corresponds to an individual datum; horizontal lines correspond to medians. (A) TFV (TAF hydrolysis product) vaginal fluid concentrations. The arrow (Day 30) corresponds to the time of Configuration B IVR removal. Paired proximal and distal vaginal fluid TFV concentrations at each timepoint were compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: Day 7, P = 0.1563; Day 14, P = 0.5625; Day 21, P > 0.9999; Day 30, P = 0.0313 (significantly different); Day 31 (washout), P = 0.8750. (B) ACV vaginal fluid concentrations. Paired proximal and distal vaginal fluid ACV concentrations at each timepoint were compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test: Day 7, P = 0.16; Day 14, P = 0.31; Day 21, P = 0.84; Day 30, P = 0.19.

Quantification of ENG in vaginal fluid samples was complicated by the wide dynamic range afforded by the rapid- and slow-releasing IVRs. While ENG levels in Configuration A (rapid-releasing ENG) were all above the lower limit of quantitation, only 50% of samples–both proximal and distal to the IVRs–were above the upper limit of quantitation. The median quantifiable ENG concentrations in this configuration were 4.8 ng mg-1 (IQR, 0.3–10.9 ng mg-1). In Configuration B (slow-releasing ENG), 54% of samples–both proximal and distal to the IVRs–were below the lower limit of quantitation. The median quantifiable ENG concentrations in this configuration were 0.2 ng mg-1 (IQR, 0.1–0.3 ng mg-1).

The analysis of EE in vaginal fluid samples by ELISA appeared to suffer from an interference precluding accurate measurements. However, EE vaginal fluid levels were consistently higher with the IVRs in place and a concentration gradient was apparent, with higher levels proximal to the IVRs. Median paired proximal:distal EE concentration ratios with the IVRs in place were 3.6 (IQR, 2.1–5.5).

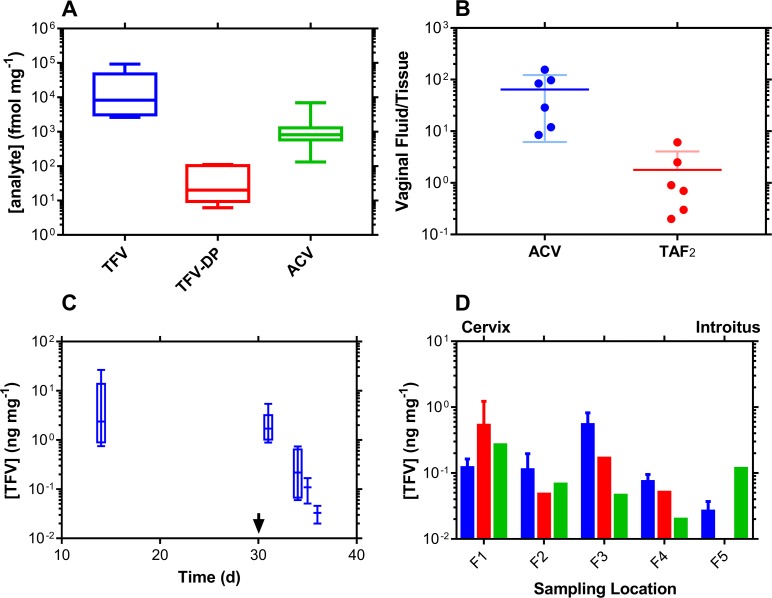

Vaginal tissue drug concentrations

Molar antiviral drug concentrations in vaginal tissue biopsy homogenate are described in Fig 6A. These include the pharmacologically active metabolite of TFV (against HIV), tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP). The CVF (ng mg-1) to vaginal tissue (ng mg-1) drug concentration ratio (Fig 6B) provides a simple measure of xenobiotic partitioning between the two anatomic compartments: the lower the ratio, the more the antiviral agent distributes into the vaginal mucosa and the higher the vaginal bioavailability. The concentration ratio for TAF2 is approximately 40 times lower than for ACV.

Fig 6. In vivo (N = 6) vaginal tissue homogenate drug levels from Configuration A and Configuration B TAF2-ACV-ENG-EE pod-IVRs.

(A) Box plots of Day 14 (Configuration A) vaginal tissue molar concentrations at pod-IVR removal. The box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles, with the horizontal line in the box representing the median; whiskers represent the lowest and highest datum. Vaginal tissue biopsies were collected distally to the pod-IVRs. Molar concentration units (fmol mg-1) were used on the y-axis to allow direct comparison between analytes. (B) Paired vaginal fluid:vaginal tissue concentration ratios of TFV (delivered as TAF2) and ACV at Day 14. The ratios provide a measure of the extent of tissue penetration for each analyte following vaginal delivery and, hence, vaginal bioavailability. (C) Box plots representing TFV washout from vaginal tissues following pod-IVR removal on Day 30 (arrow). The box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles, with the horizontal line in the box representing the median; whiskers represent the lowest and highest datum. Vaginal tissue biopsies were collected on Day 14 and Day 31distally to the pod-IVRs. For Day 34–36 samples, collected at necropsy, only vaginal tissue TFV concentrations at locations F3 and F4 (see panel D) were used in the analysis to maintain consistency is sampling location (i.e., distal to the pod-IVRs). The median terminal half-life of TFV in vaginal tissues was found to be 18 h (IQR, 13–30 h). (D) Longitudinal distribution of TFV concentrations in whole vaginal tracts collected at necropsy (Day 34–36), i.e., following removal of the second set of IVRs. The vaginal tracts were divided into uniform segments (F1-F5) spanning from the cervix (F1, proximal to the IVR) to the introitus (F5) and the homogenized sections analyzed for TFV concentrations. Blue, Day 34 (N = 2); red, Day 35 (N = 2); and green, Day 36 (N = 2).

The measurement of TFV levels post-IVR removal on Day 30 allows the drug washout kinetics to be analyzed (Fig 6C). A terminal half-life of elimination of 18 h (IQR, 13–30 h) was calculated from these data. The longitudinal (cervix to introitus) TFV distribution in vaginal tissue homogenate on three successive days during washout (i.e., after IVR removal) is shown in Fig 6D. No systematic pattern could be identified.

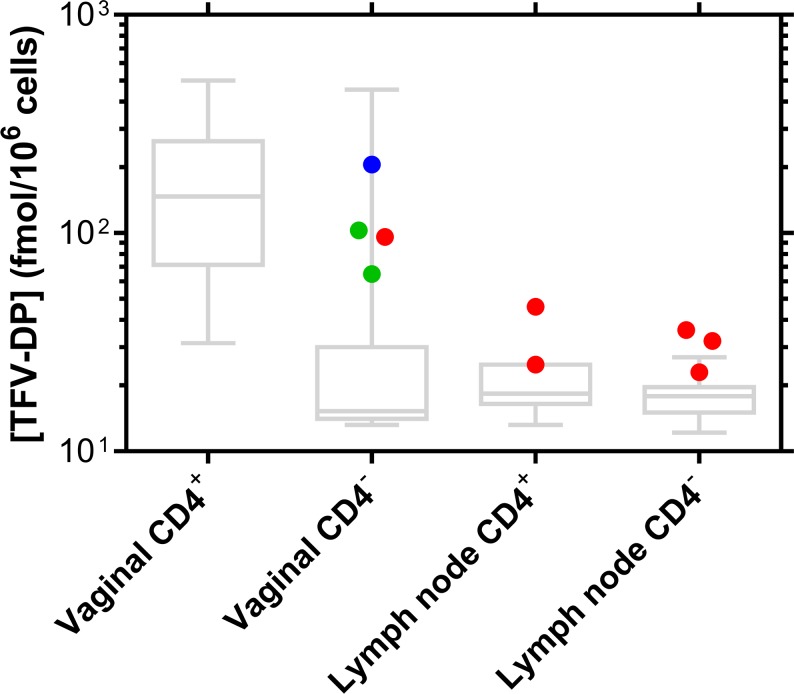

Intracellular TFV-DP concentrations

Intracellular TFV-DP concentrations in CD4+ and CD4- cells isolated from vaginal tissues and inguinal and iliac lymph node tissues at necropsy and during drug washout (Days 34–36, the IVRs were removed on Day 30) are presented in Fig 7. The small number of CD4+ cells isolated from vaginal tract sections precluded the quantitation of TFV-DP in these samples, as illustrated by the corresponding high LLOQ box plot in Fig 7.

Fig 7. Intracellular TFV-DP concentrations in vaginal tissues and inguinal and iliac lymph nodes collected at necropsy.

Blue, Day 34 (N = 2); red, Day 35 (N = 2); and green, Day 36 (N = 2). The intracellular TFV-DP levels are maintained 4–6 days after pod-IVR removal on Day 30. The box plots represent the analytical lower limits of quantitation (LLOQ) associated with the TFV-DP measurements, where the box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles, with the horizontal line in the box representing the median; whiskers represent the lowest and highest datum. The assay has an LLOQ of 50 fmol per sample, which is divided by the number of cells collected in each sample to afford the individual LLOQs represented here.

Systemic (plasma) drug concentrations

Systemic drug concentrations resulting from pod-IVR use are summarized in Table 4 for both formulations. Plasma TFV was quantified in 92–100%, depending on the pod-IVR formulation (Table 4). In previous studies on TFV or TDF IVR delivery in pigtailed macaques [39, 43, 50], plasma TFV concentrations usually are not quantifiable in most samples. However, the analytical methods for measuring plasma TFV in these prior studies had higher LLOQs (1 ng mL-1 or higher) than in our current study (0.31 ng mL-1, Table 2), possibly explaining the observation.

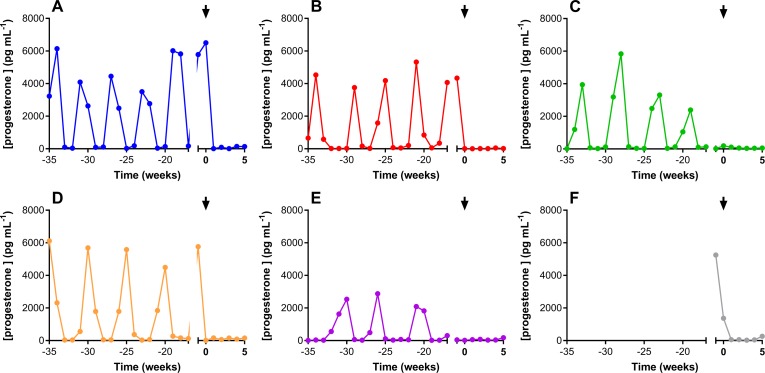

Plasma progesterone levels over a 40-week period are presented in Fig 8. Use of the Configuration A pod-IVRs started on Week 0, as indicted by the arrow in all panels. Endogenous progesterone production was effectively inhibited in all animals by the higher ENG-releasing IVR and maintained by the lower-releasing configuration.

Fig 8. Plasma progesterone concentrations over 40-week period.

Each panel represents one animal; the arrow indicates the placement of the Configuration A pod-IVR (week 0).

Discussion

The primary objective of the current study was to assess the PK in pigtailed macaques of a novel, multipurpose IVR for the prevention of HIV, HSV, and unintended pregnancy. We were able to utilize SHIV-infected macaques for a PK pilot study of short duration, followed by necropsy to obtain samples that are not feasible with a traditional PK design. Consequently, the IVRs were evaluated for ca. two weeks for each configuration. We acknowledge that a longer evaluation period, possibly spanning multiple, monthly pod-IVR changes, would have been beneficial. However, the time limitation for studies in infected animals scheduled for necropsy is restricted to limit pain and suffering and traditional, non-terminal PK studies are not amenable to the extensive tissue collection described here. Based on results from the current report, an expanded PK evaluation of the pod-IVR configuration described can be carried out in uninfected animals in future studies. The in vivo release rates, measured based on the residual drug content of the used devices, was less than 1 mg d-1 for all drugs (Table 3). A human-sized pod-IVR can accommodate up to 10 pods, ca. 45 mg each [36, 48]. Assuming two pods for the hormonal contraceptives and four pods for each of the antiviral agents, release rates well in excess of 1 mg d-1 would be feasible for one month while still remaining within the predicted linear release regime when 20% or more of the drug payload is present in the pods [48]. Given the low release of ENG (0.12 mg d-1) and EE (0.015 mg d-1) required for efficacy of the NuvaRing in humans, the highest required dosing would be for the two antiviral agents, and release rates of up to 5 mg d-1 would be feasible from a 28-day pod-IVR.

Rigorous PK testing in nonhuman primates constitutes a key preclinical evaluation in the development of vaginal drug delivery products. The pigtailed macaque model is particularly relevant because of its similarities with the human menstrual cycle, vaginal architecture and microbiome, and the ability to conduct efficacy studies with simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) [43, 47, 50–52]. The implications of our findings are discussed below in the context of developing a viable MPT candidate targeted at resource-poor regions.

Biomedical product design considerations

Multipurpose IVRs will need to simultaneously deliver API combinations at independently controlled rates [37, 38]. Conventional IVR technologies–i.e., matrix and reservoir rings [26]–are based on API diffusion through the elastomer backbone that makes up the ring. This approach complicates the development of combination IVRs partially explaining why, to date, all such MPT IVRs have delivered two APIs [53, 54], with the exception of the MZCL IVR under development by the Population Council [55] and the pod-IVR described here [38]. We have developed an innovative pod-IVR platform that can simultaneously deliver multiple drugs in a modular fashion [36]. The polymer-coated drug cores, referred to as pods, are embedded in an unmedicated ring. This approach leads to a number of important benefits, discussed in detail elsewhere [26, 36]. In the context of combination IVRs as an MPT, the pod-IVR design readily enables the delivery of three or more drugs from a single device, as described in the literature [38, 39] and below.

Adherence to IVR use

Two clinical trials were the first to evaluate the efficacy of an ARV IVR for HIV PrEP [33, 56]. Both found that a significant proportion of trial participants, particularly young women, did not adhere to study product use. These results raised concerns on the viability of IVRs for HIV PrEP in resource-limited regions. However, IVRs also are a new, female-controlled option in sub-Saharan Africa where contraceptive IVRs are not commonly used as in the developed world. Many believe [30, 31, 57–59] that adherence to IVR use for HIV PrEP will increase as familiarity with the devices increases and the trials transition into open-label phases. The same trend was observed with oral Truvada (TDF-FTC)/Viread (TDF) where adherence, and hence HIV PrEP efficacy, increased dramatically when moving from the initial, blinded, placebo-controlled trials to the open-label follow-on trials [20, 60–62].

The inclusion of a contraceptive component in MPT IVRs is believed by many to significantly motivate product adherence for HIV PrEP [30, 31, 57–59], thereby improving efficacy. The contraceptive component may be especially important for young women (18–21 years of age), the age group that was least adherent in the two phase 3 dapivirine IVR trials [33, 56]. However, the best approach is arguably to give women options that best suit their needs. For women that prefer no contraception, or a different contraceptive regimen (e.g., oral, injectable, or implant), the pod-IVR gives physicians additional versatility.

The choice of antiviral agents and PK implications

The first MPT IVR for the prevention of HIV and HSV infection delivered a combination of TFV and ACV in the ovine model [37]. We have subsequently shown that the vaginal tissue bioavailability in sheep of the prodrug TDF was nearly 100 times higher than for the parent drug TFV [63]. To date, there have been no reports on the delivery of TAF (or TAF2) via IVR. Tenofovir alafenamide was approved by the FDA on November 5, 2015 for the treatment of HIV/AIDS and is being touted as the successor to TDF [64]. Because of its high potency against HIV [65], TAF is administered orally at a 30-fold lower dose (10 mg) than TDF (300 mg) and accumulates selectively in lymphatic tissue and immune cells, the targets for HIV replication, potentially also leading to a higher resistance barrier [66]. Tenofovir alafenamide has an excellent safety profile [67], with a much lower risk of kidney toxicity or bone density changes than TDF [68]. The high vaginal bioavailability of TAF in pigtailed macaques demonstrated here (Fig 4B) is an encouraging result.

In the present study, pod-IVRs delivered TAF2 in pigtailed macaques at a similar, albeit slightly lower, rate than TDF (Fig 4A) in a previous TDF-FTC pod-IVR study, also in pigtailed macaques [39]. The median TFV vaginal fluid levels from TAF2 delivery varied between 3.9 and 13.3 ng mg-1, depending on the IVR configuration and sampling location (Table 4). These values are considerably lower than corresponding median TFV concentrations (110–180 g mg-1, depending on the sampling site) following TDF delivery [39]. The median TFV (2.4 ng mg-1) exposure in vaginal tissue homogenate following TAF2 delivery also was considerably lower than corresponding median TFV concentrations (28 ng mg-1) resulting from TDF delivery [39]. Vaginal tissue homogenate TFV-DP concentrations were not measured in our previous study, so that comparison is not possible. The low CD4+ cell count in vaginal tissues prevented the washout kinetics of intracellular TFV-DP in these cell types to be measured. It should be noted that vaginal tissue TFV and TFV-DP concentrations have limited value as surrogates for the prediction of efficacy in HIV PrEP when comparing two different TFV prodrugs delivered topically. TAF delivers TFV more efficiently into PMBCs than TDF or TFV [69] and in vitro TAF was found to be >600-fold and 80-fold more potent than parent TFV in CD4+ T-cells and MDMs, respectively [70]. Concentrations of TFV and TFV-DP in vaginal tissue homogenate from TDF therefore may not be predictive of intracellular TFV-DP levels in HIV target cells resulting from topical TAF2 delivery, and vice versa.

The results of our studies do not definitively identify TAF2 or TDF as a superior candidate for vaginal HIV PrEP. Given the different drug distribution of the two TFV prodrugs, it is challenging to make meaningful efficacy predictions based on vaginal fluid drug levels. However, the above TDF-FTC pod-IVR was fully protective of vaginal SHIV infection in pigtailed macaques [52], but also included the delivery of FTC in addition to TDF. Smith et al. showed that a reservoir IVR delivering only TDF afforded full protection from infection in pigtailed macaques using the rigorous, repeat low dose SHIV challenge model [50]. Vaginal tissue TFV levels obtained with these IVRs were highly variable ranging between 0.1–100 ng mg-1, with means around 10 ng mg-1 well within the range observed here (median, 2.4 ng mg-1; IQR, 1.2–7.8 ng mg-1, Table 4). These results suggest that the TAF2 release rates from the IVR may be sufficient for SHIV protection in macaques, although they could easily be increased in a future study [48]. The vaginal TAF2 or TDF concentrations via IVR delivery required for protection from HIV infection in humans are unknown.

Acyclovir is a potent, FDA-approved antiviral agent for the treatment of HSV infections [71, 72]. While it has been suggested that TDF could be used vaginally for the simultaneous prevention of HIV and HSV [73, 74], ACV represents a clearly superior candidate for topical HSV prevention as it is 100-fold more potent in vitro [75]. Acyclovir exhibited a low vaginal bioavailability relative to TAF (Fig 4B), a result that was not unexpected given its oral bioavailability in the 10–20% range [76]. The low oral bioavailability of ACV led to the development of the L-valyl ester prodrug, valacyclovir (VACV), which was found to exhibit a three- to five-fold higher oral bioavailability clinically than the parent compound [76]. Valacyclovir is a substrate for intestinal and renal peptide transporters (PepT1 and PepT2), largely explaining its enhanced oral bioavailability relative to ACV [77, 78]. Unfortunately, PepT1 and PepT2 were found to be underexpressed in human vaginal tissues [79], explaining why ACV is being used at this stage of product development [37, 80, 81].

The ACV concentration required to reduce virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) by 50% (EC50) during in vitro studies using clinical HSV-2 isolates was 0.04–0.2 ng μL-1 [75, 82]. These values refer to ACV levels in the culture medium, not the concentrations in HSV-infected cells where ACV is selectively monophosphorylated [83]. Unlike HIV, HSV can infect vaginal epithelial cells. Median ACV concentrations in CVF–the appropriate correlate for in vitro EC50 values–achieved here were 50–100 times higher (Table 4) than the highest of the above EC50 values. The dose of ACV needed to suppress vaginal HSV replication or prevent acquisition in humans is unknown. A regimen of oral ACV (200 mg) taken five times daily for 10 days led to peak ACV concentrations in vaginal fluids in the 0.18–0.81 ng mg-1 range, 0.5–1 h after the final oral dose [84, 85], 14 to 165 times lower than the vaginal fluid ACV concentrations obtained here (median: 11.7–29.7 ng mg-1, depending on the IVR configuration and sampling location, Table 4).

Hormonal contraception in MPT IVRs

In IVR-based hormonal contraception, progestin-estrogen combinations have demonstrated superior clinical efficacy to devices delivering only progestin [86]. Several large multicenter trials evaluating a matrix IVR delivering the progestin levonorgestrel (LNG) found pregnancy rates at 12 months between 3.7% [87] and 5.1% [88]. In contrast, the NuvaRing®, which delivers a combination of ENG and EE, demonstrated clinical efficacy in excess of 99% in Europe and in the United States [89–91]. The ENG:EE daily in vivo release ratios of Configuration A and Configuration B pod-IVRs were targeted to bracket the corresponding value obtained with the NuvaRing. These targets were achieved and plasma progestin levels during the 30 days of IVR use were effectively suppressed in all animals.

A number of MPT IVRs under development are based on progestin-only contraception using LNG [53–55]. There is growing concern, largely based on observational evidence from injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) [92], that an LNG-only regimen as part of an MPT may lead to an increased risk of HIV acquisition in women [93, 94]. More research is needed to further investigate the potential links between hormone exposure in the vaginal mucosa and STI susceptibility, including HIV.

In conclusion, topical administration of four drugs (one antiretroviral agent, one antiherpetic agent, and a contraceptive estrogen-progestin combination) from pod-IVRs in pigtailed macaques demonstrated preliminary safety while exhibiting sustained and controlled drug release over 30 days of consecutive product use. Given that all drugs achieved either drug concentrations associated with antiviral effect in other studies (TAF2, AVC) or demonstrated biologic activity in our study (ENG:EE suppressing progestin concentration), our pod-IVR holds significant potential for the prevention of vaginal HIV and HSV acquisition, along with unintended pregnancy, and merits further investigation.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We acknowledge the following members of the CDC DHAP Laboratory Branch/Preclinical Evaluation Team for their contributions to our nonhuman primate research: David Garber, James Mitchell, Frank Deyounks, and Kristen Kelley. The use of trade names is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part through institutional funds at the Oak Crest Institute of Science and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (www.niaid.nih.gov) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U19AI113048. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Libra Management Group, a commercial company, is the employer of several authors of this manuscript (SE and JZ). The funder provided support in the form of salaries for authors (SE and JZ), but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the “author contributions” section.

References

- 1.Birx DL. Delivering an AIDS-free Generation. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fast-Track: Ending the AIDS Epidemic by 2030. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prevention Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald A, Link K. Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Seropositive Persons: a Meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(1):45–52. doi: 10.1086/338231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renzi C, Douglas JM, Foster M, Critchlow CW, Ashley-Morrow R, Buchbinder SP, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection as a Risk Factor for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Acquisition in Men Who Have Sex with Men. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(1):19–25. doi: 10.1086/345867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds SJ, Risbud AR, Shepherd ME, Zenilman JM, Brookmeyer RS, Paranjape RS, et al. Recent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection and the Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Acquisition in India. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(10):1513–21. doi: 10.1086/368357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mugo N, Dadabhai SS, Bunnell R, Williamson J, Bennett E, Baya I, et al. Prevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection, Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Coinfection, and Associated Risk Factors in a National, Population-based Survey in Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):1059–66. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e60b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corey L, Wald A, Celum CL, Quinn TC. The Effects of Herpes Simplex Virus-2 on HIV-1 Acquisition and Transmission: A Review of Two Overlapping Epidemics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):435–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes Simplex Virus 2 Infection Increases HIV Acquisition in Men and Women: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Aids. 2006;20(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific Prevalence of Infection with Herpes Simplex Virus Types 2 and 1: A Global Review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:S3–S28. doi: 10.1086/343739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mbopi-Keou FX, Gresenguet G, Mayaud P, Weiss HA, Gopal R, Matta M, et al. Interactions Between Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection in African Women: Opportunities for Intervention. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(4):1090–6. doi: 10.1086/315836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rollenhagen C, Lathrop MJ, Macura SL, Doncel GF, Asin SN. Herpes Simplex Virus Type-2 Stimulates HIV-1 Replication in Cervical Tissues: Implications for HIV-1 Transmission and Efficacy of Anti-HIV-1 Microbicides. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7(5):1165–74. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman EE, Orroth KK, White RG, Glynn JR, Bakker R, Boily MC, et al. Proportion of New HIV Infections Attributable to Herpes Simplex 2 Increases over Time: Simulations of the Changing Role of Sexually Transmitted Infections in sub-Saharan African HIV Epidemics. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:I17–I24. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Heterosexual HIV Transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Infection in Injecting Drug Users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, Pialoux G, Cotte L, Charreau I, et al. On-demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2237–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, Nguyen DP, Phengrasamy T, Silverberg MJ, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Large Integrated Health Care System: Adherence, Renal Safety, and Discontinuation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):540–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent the Acquisition of HIV-1 Infection (PROUD): Effectiveness Results from the Pilot Phase of a Pragmatic Open-label Randomised Trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the Divergent Results of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Trials for HIV Prevention. Aids. 2012;26(7):F13–F9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruse W, Eggertkruse W, Rampmaier J, Runnebaum B, Weber E. Dosage Frequency and Drug Compliance Behavior—a Comparative Study on Compliance with a Medication to Be Taken Twice or 4 Times Daily. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;41(6):589–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00314990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sershen S, West J. Implantable, Polymeric Systems for Modulated Drug Delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(9):1225–35. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00090-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kutilek VD, Sheeter DA, Elder JH, Torbett BE. Is Resistance Futile? Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2003;3(4)::295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, Sian S, Smith DB. Comparing Adherence and Persistence Across 6 Chronic Medication Classes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(9):728–40. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.9.728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss JA, Baum MM. Microbicide Vaginal Rings In: das Neves J, Sarmento B, editors. Drug Delivery and Development of Anti-HIV Microbicides. Singapore: Pan Stanford Publishing; 2014. p. 221–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGowan I. Injectable and Implantable Antiretroviral Strategies for HIV Prevention. Future Virol. 2015;10(10):1163–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friend DR, Doncel GF. Combining Prevention of HIV-1, Other Sexually Transmitted Infections and Unintended Pregnancies: Development of Dual-protection Technologies. Antiviral Res. 2010;88:S47–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friend DR. Drug Delivery in Multiple Indication (Multipurpose) Prevention Technologies: Systems to Prevent HIV-1 Transmission and Unintended Pregnancies or HSV-2 Transmission. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9(4):417–27. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.668183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friend DR. An Update on Multipurpose Prevention Technologies for the Prevention of HIV Transmission and Pregnancy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13(4):533–45. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2016.1134485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quaife M, Terris-Prestholt F, Vickerman P. The Promise of Multipurpose Pregnancy, STI, and HIV Prevention. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terris-Prestholt F, Quaife M, Vickerman P. Parameterising User Uptake in Economic Evaluations: The role of discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2016;25:116–23. doi: 10.1002/hec.3297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a Vaginal Ring Containing Dapivirine for HIV-1 Prevention in Women. N Engl J Med. 2016:Epub ahead of print Feb. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu D, Shi B, Wang F, Hung R, Yu C, inventors; Gilead Sciences, Inc., assignee. Tenofovir Alafenamide Hemifumarate. USA patent U.S. Patent 8,754,065 B2. 2014 Jun. 17, 2014.

- 35.Promadej-Lanier N, Smith JM, Srinivasan P, McCoy CF, Butera S, Woolfson AD, et al. Development and Evaluation of a Vaginal Ring Device for Sustained Delivery of HIV Microbicides to Non-human Primates. J Med Primatol. 2009;38(4):263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2009.00354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baum MM, Butkyavichene I, Gilman J, Kennedy S, Kopin E, Malone AM, et al. An Intravaginal Ring for the Simultaneous Delivery of Multiple Drugs. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(8):2833–43. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3857731. doi: 10.1002/jps.23208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moss JA, Malone AM, Smith TJ, Kennedy S, Kopin E, Nguyen C, et al. Simultaneous Delivery of Tenofovir and Acyclovir via an Intravaginal Ring. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(2):875–82. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3264253. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05662-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moss JA, Malone AM, Smith TJ, Kennedy S, Nguyen C, Vincent KL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a Multipurpose Pod-intravaginal Ring Simultaneously Delivering Five Drugs in the Ovine Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(8):3994–7. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3719699. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00547-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss JA, Srinivasan P, Smith TJ, Butkyavichene I, Lopez G, Brooks AA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and Preliminary Safety Study of Pod-Intravaginal Rings Delivering Antiretroviral Combinations for HIV Prophylaxis in a Macaque Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(9):5125–35. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4135875. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02871-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owen DH, Katz DF. A Vaginal Fluid Simulant. Contraception. 1999;59(2):91–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birkus G, Kutty N, He GX, Mulato A, Lee W, McDermott M, et al. Activation of 9-[(R)-2-[[(S)-[[(S)-1-(Isopropoxycarbonyl)ethyl]amino]phenoxyphosphinyl]-methoxy]propyl]adenine (GS-7340) and Other Tenofovir Phosphonoamidate Prodrugs by Human Proteases. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(1):92–100. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babusis D, Phan TK, Lee WA, Watkins WJ, Ray AS. Mechanism for Effective Lymphoid Cell and Tissue Loading Following Oral Administration of Nucleotide Prodrug GS-7340. Mol Pharmaceut. 2013;10(2):459–66. doi: 10.1021/mp3002045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moss JA, Malone AM, Smith TJ, Butkyavichene I, Cortez C, Gilman J, et al. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Intravaginal Rings Delivering Tenofovir in Pig-tailed Macaques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(11):5952–60. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3486594. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01198-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louissaint NA, Cao YJ, Skipper PL, Liberman RG, Tannenbaum SR, Nimmagadda S, et al. Single Dose Pharmacokinetics of Oral Tenofovir in Plasma, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells, Colonic Tissue, and Vaginal Tissue. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(11):1443–50. doi: 10.1089/AID.2013.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunawardana M, Remedios-Chan M, Miller CS, Fanter R, Yang F, Marzinke MA, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Long-acting Tenofovir Alafenamide (GS-7340) Subdermal Implant for HIV Prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015:Epub ahead of print Apr. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendrix CW, Chen BA, Guddera V, Hoesley C, Justman J, Nakabiito C, et al. MTN-001: Randomized Pharmacokinetic Cross-over Study Comparing Tenofovir Vaginal Gel and Oral Tablets in Vaginal Tissue and Other Compartments. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobard C, Sharma S, Martin A, Pau CP, Holder A, Kuklenyik Z, et al. Durable Protection from Vaginal Simian-human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Macaques by Tenofovir Gel and its Relationship to Drug Levels in Tissue. J Virol. 2012;86(2):718–25. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05842-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baum MM, Butkyavichene I, Churchman SA, Lopez G, Miller CS, Smith TJ, et al. An Intravaginal Ring for the Sustained Delivery of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. Int J Pharm. 2015;495(1):579–87. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMCID: PMC4609628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moss JA, Butkyavichene I, Churchman SA, Gunawardana M, Fanter R, Miller CS, et al. Combination Pod-intravaginal Ring Delivers Antiretroviral Agents for HIV Prophylaxis: Pharmacokinetic Evaluation in an Ovine Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(6):3759–66. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00391-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith JM, Rastogi R, Teller RS, Srinivasan P, Mesquita PM, Nagaraja U, et al. Intravaginal Ring Eluting Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Completely Protects Macaques from Multiple Vaginal Simian-HIV Challenges. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(40):16145–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311355110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parikh UM, Dobard C, Sharma S, Cong ME, Jia HW, Martin A, et al. Complete Protection from Repeated Vaginal Simian-human Immunodeficiency Virus Exposures in Macaques by a Topical Gel Containing Tenofovir Alone or with Emtricitabine. J Virol. 2009;83(20):10358–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01073-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srinivasan P, Moss JA, Gunawardana M, Churchman SA, Yang F, Dinh CT, et al. Topical Delivery of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate and Emtricitabine from Pod-intravaginal Rings Protect Macaques from Multiple SHIV Exposures. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157061 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4898685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark JT, Clark MR, Shelke NB, Johnson TJ, Smith EM, Andreasen AK, et al. Engineering a Segmented Dual-reservoir Polyurethane Intravaginal Ring for Simultaneous Prevention of HIV Transmission and Unwanted Pregnancy. PLoS One. 2014;9(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boyd P, Fetherston SM, McCoy CF, Major I, Murphy DJ, Kumar S, et al. Matrix and Reservoir-type Multipurpose Vaginal Rings for Controlled Release of Dapivirine and Levonorgestrel. Int J Pharm. 2016;511(1):619–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ugaonkar SR, Wesenberg A, Wilk J, Seidor S, Mizenina O, Kizima L, et al. A Novel Intravaginal Ring to Prevent HIV-1, HSV-2, HPV, and Unintended Pregnancy. J Control Release. 2015;213:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nel A, van Niekerk N, Kapiga S, Bekker LG, Gama C, Gill K, et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for HIV Prevention in Women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2133–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brady M, Manning J. Lessons from Reproductive Health to Inform Multipurpose Prevention Technologies: Don't Reinvent the Wheel. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:S25–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boonstra H, Barot S, Lusti-Narasimhan M. Making the Case for Multipurpose Prevention Technologies: the Socio-epidemiological Rationale. BJOG. 2014;121:23–6. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woodsong C, Holt JDS. Acceptability and Preferences for Vaginal Dosage Forms Intended for Prevention of HIV or HIV and Pregnancy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;92:146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baeten J, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, Mugo N, Katabira E, Bukusi E, et al., editors. Near Elimination of HIV Transmission in a Demonstration Project of PrEP and ART. 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 2015 Feb. 23–26, 2015; Seattle, WA: CROI, Alexandria, VA.

- 61.Amico KR, Wallace M, Bekker LG, Roux S, Atujuna M, Sebastian E, et al. Experiences with HPTN 067/ADAPT Study Provided Open-Label PrEP Among Women in Cape Town: Facilitators and Barriers Within a Mutuality Framework. AIDS Behav. 2016:Epub ahead of print Jun 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molina J-M, Charreau I, Spire B, Cotte L, Pialoux, Capitant C, et al., editors. On Demand PrEP With Oral TDF-FTC in the Open-Label Phase of the ANRS IPERGAY Trial. 2016 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 2016 Feb. 22–25, 2016; Boston, MA: CROI, Alexandria, VA.

- 63.Moss JA, Baum MM, Malone AM, Kennedy S, Kopin E, Nguyen C, et al. Tenofovir and Tenofovir Disoproxil Pharmacokinetics from Intravaginal Rings. Aids. 2012;26(6):707–10. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3855348. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283509abb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Clercq E. Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF) as the Successor of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF). Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;119:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ray AS, Fordyce MW, Hitchcock MJM. Tenofovir Alafenamide: A Novel Prodrug of Tenofovir for the Treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Antiviral Res. 2016;125:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Margot NA, Liu Y, Miller MD, Callebaut C. High Resistance Barrier to Tenofovir Alafenamide is Driven by Higher Loading of Tenofovir Diphosphate into Target Cells Compared to Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. Antiviral Res. 2016;132:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gibson AK, Shah BM, Nambiar PH, Schafer JJ. Tenofovir Alafenamide: A Review of Its Use in the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):942–52. doi: 10.1177/1060028016660812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Casado JL. Renal and Bone Toxicity with the Use of Tenofovir: Understanding at the End. Aids Rev. 2016;18(2):59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee WA, He GX, Eisenberg E, Cihlar T, Swaminathan S, Mulato A, et al. Selective Intracellular Activation of a Novel Prodrug of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Tenofovir Leads to Preferential Distribution and Accumulation in Lymphatic Tissue. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(5):1898–906. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1898-1906.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bam RA, Birkus G, Babusis D, Cihlar T, Yant SR. Metabolism and Antiretroviral Activity of Tenofovir Alafenamide in CD4+ T-cells and Macrophages from Demographically Diverse Donors. Antivir Ther. 2014;19(7):669–77. doi: 10.3851/IMP2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morse GD, Shelton MJ, Odonnell AM. Comparative Pharmacokinetics of Antiviral Nucleoside Analogs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;24(2):101–23. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199324020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perry CM, Faulds D. Valaciclovir—A Review of its Antiviral Activity, Pharmacokinetic Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy in Herpesvirus Infections. Drugs. 1996;52(5):754–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mesquita PMM, Rastogi R, Segarra TJ, Teller RS, Torres NM, Huber AM, et al. Intravaginal Ring Delivery of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate for Prevention of HIV and Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(7):1730–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nixon B, Jandl T, Teller RS, Taneva E, Wang YH, Nagaraja U, et al. Vaginally Delivered Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Provides Greater Protection than Tenofovir against Genital Herpes in a Murine Model of Efficacy and Safety. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(2):1153–60. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01818-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andrei G, Lisco A, Vanpouille C, Introini A, Balestra E, van den Oord J, et al. Topical Tenofovir, a Microbicide Effective against HIV, Inhibits Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(4):379–89. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weller S, Blum MR, Doucette M, Burnette T, Cederberg DM, Demiranda P, et al. Pharmacokinetics of the Acyclovir Pro-drug Valaciclovir after Escalating Single-dose and Multiple-dose Administration to Normal Volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54(6):595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Balimane PV, Tamai I, Guo AL, Nakanishi T, Kitada H, Leibach FH, et al. Direct Evidence for Peptide Transporter (PepT1)-mediated Uptake of a Nonpeptide Prodrug, Valacyclovir. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250(2):246–51. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ganapathy ME, Huang W, Wang H, Ganapathy V, Leibach FH. Valacycloviv: A Substrate for the Intestinal and Renal Peptide Transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246(2):470–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gunawardana M, Mullen M, Moss JA, Pyles RB, Nusbaum RJ, Vincent KL, et al. Global Expression of Molecular Transporters in the Human Vaginal Tract: Implications for HIV Chemoprophylaxis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77340 PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3797116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Keller MJ, Malone AM, Carpenter CA, Lo Y, Huang M, Corey L, et al. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Acyclovir in Women Following Release From a Silicone Elastomer Vaginal Ring. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(8):2005–12. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3394441. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ursell LK, Gunawardana M, Chang S, Mullen M, Moss JA, Herold BC, et al. Comparison of the Vaginal Microbial Communities in HSV-2 Seropositive Women Receiving Medicated Intravaginal Rings. Antiviral Res. 2014;102:87–94. PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4006976. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Furman PA, Fyfe JA, Stclair MH, Weinhold K, Rideout JL, Freeman GA, et al. Phosphorylation of 3'-Azido-3'-deoxythymidine and Selective Interaction of the 5'-Triphosphate with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Reverse Transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(21):8333–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller WH, Miller RL. Phosphorylation of Acyclovir (Acycloguanosine) Monophosphate by GMP Kinase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(15):7204–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Van Dyke RB, Connor JD, Wyborny C, Hintz M, Keeney RE. Pharmacokinetics of Orally-administered Acyclovir in Patients with Herpes Progenitalis. Am J Med. 1982;73(1A):172–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90085-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thurman AR, Clark MR, Doncel GF. Multipurpose Prevention Technologies: Biomedical Tools to Prevent HIV-1, HSV-2, and Unintended Pregnancies. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:429403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brache V, Faundes A. Contraceptive Vaginal Rings: a Review. Contraception. 2010;82(5):418–27. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koetsawang S, Ji G, Krishna U, Cuadros A, Dhall GI, Wyss R, et al. Microdose Intravaginal Levonorgestrel Contraception: A Multicenter Clinical Trial. 1. Contraceptive Efficacy and Side-Effects. Contraception. 1990;41(2):105–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sahota J, Barnes PMF, Mansfield E, Bradley JL, Kirkman RJE. Initial UK Experience of the Levonorgestrel-releasing Contraceptive Intravaginal Ring. Adv Contracept. 1999;15(4):313–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1006748626008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roumen F. Contraceptive Efficacy and Tolerability with a Novel Combined Contraceptive Vaginal Ring, NuvaRing. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2002;7:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oddsson K, Leifels-Fischer B, de Melo NR, Wiel-Masson D, Benedetto C, Verhoeven CHJ, et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Contraceptive Vaginal Ring (NuvaRing) Compared with a Combined Oral Contraceptive: a 1-Year Randomized Trial. Contraception. 2005;71(3):176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Madden T, Blumenthal P. Contraceptive Vaginal Ring. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(4):878–85. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318159c07e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Polis CB, Curtis KM, Hannaford PC, Phillips SJ, Chipato T, Kiarie JN, et al. An Updated Systematic Review of Epidemiological Evidence on Hormonal Contraceptive Methods and HIV Acquisition in Women. Aids. 2016;30(17):2665–83. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Polis CB, Phillips SJ, Hillier SL, Achilles SL. Levonorgestrel in Contraceptives and Multipurpose Prevention Technologies: Does this Progestin Increase HIV Risk or Interact with Antiretrovirals? Aids. 2016;30(17):2571–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Seidman D, Hemmerling A, Smith-McCune K. Emerging Technologies to Prevent Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Infections in Women. Semin Reprod Med. 2016;34(3):159–67. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1571436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.