Summary

Objective

To investigate whether men with obstructive voiding symptoms are at increased risk for being diagnosed with prostate cancer (PCa) within the Gothenburg randomized population-based prostate cancer screening trial.

Subjects and Methods

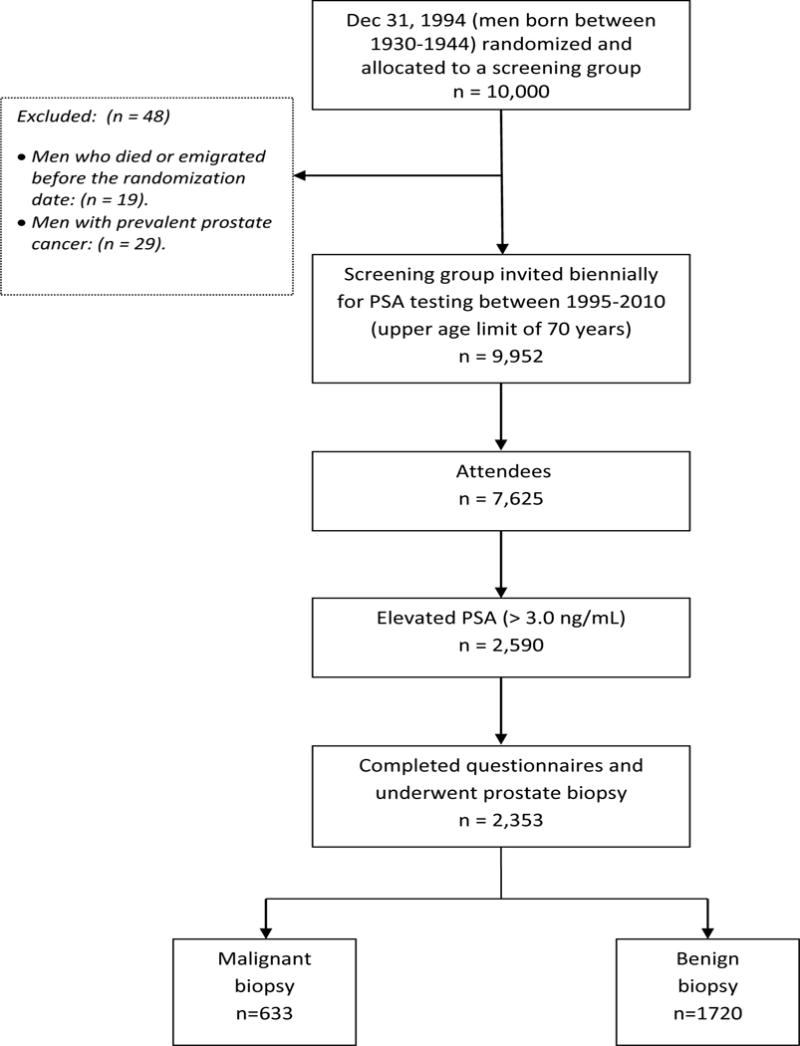

In 1995, 20,000 men born between 1930 and 1944 were randomly selected from the population register and randomized to either a screening group (n = 10,000), invited for total prostate-specific antigen (T-PSA) testing every second year until they reached an upper age-limit pending between 67–71 years, or to a control group not invited (n = 10,000).

Men with a PSA level of ≥ 3.0 ng/ mL were offered further examination with prostate biopsies. Immediately prior to the physician’s examination a self-administered, study-specific questionnaire was completed including one question concerning obstructive voiding symptoms.

Multivariate logistic regression modeling was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for associations of age, T-PSA, free-to-total (F/T) PSA ratio, prostate volume and the presence of voiding symptoms in prostate cancer risk. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Between 1995 and 2010 there were 2,590 men who had an elevated PSA level (≥ 3.0 ng/mL) at least once during the study. Of these, 2,353 men (91%) accepted further clinical examination with trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) and prostate biopsies. 633/2,353 men had PCa (27%) on biopsy and 1,720/2,353 men (73%) had a benign pathology.

Men with PCa reported a lower frequency of voiding symptoms (24% versus 31%, p < 0.001), independent of age and locally advanced tumors (T2b-T4). In the multivariate logistic regression model increasing age and T-PSA were positively associated with PCa while prostate volume, F/T PSA ratio and the presence of voiding symptoms were all inversely associated with the risk of detecting PCa in a screening setting. This inverse association of voiding symptoms and PCa detection was restricted to men with large prostates (> 37.8 cm3); 15% in men with voiding symptoms versus 22% in asymptomatic men (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The presence of voiding symptoms should not be a decision tool for deciding which men with an elevated PSA level should be offered biopsies of the prostate.

Keywords: randomized controlled trial, PSA screening, prostatic neoplasm, lower urinary tract symptoms

Introduction

Men with voiding symptoms often have an underlying fear of prostate cancer (PCa) [1, 2]. Studies have shown that the majority of clinicians would carry out PSA testing in men complaining of urinary symptoms [3, 4] despite the lack of support for this in the literature [3]. In Denmark, one-third of the general practitioners state that they would measure PSA in a male patient complaining of LUTS [5]. Schulman et al. showed in a large European survey [6] that only 1% of the general population was aware of that PCa could be asymptomatic. 86% of the respondents identified urinary symptoms as signs of the disease. In the Swedish national guidelines for PSA testing [7], men are informed that “prostate cancer is the most common malignancy among Swedish men, and pain and voiding symptoms are common”. Most GPs and urologists routinely check the PSA level in men seeking medical care for voiding symptoms, even though the test has limited specificity when it comes to distinguishing between benign and malignant disease [8]. In the male population over 50 years, the prevalence of LUTS is approximately 30–50% [9–11]. LUTS can be categorized as storage symptoms, voiding symptoms or postmicturition symptoms.

Recently, the mortality data from the Gothenburg randomized population-based cancer screening trial showed a 44% reduction in PCa specific mortality as a result of PSA screening [12]. These findings are likely to increase awareness and requests for PSA testing among men. In this study we wanted to evaluate the presence of voiding symptoms as a pre-biopsy parameter that might predict positive biopsies, i.e. if men with an elevated PSA level and voiding symptoms are at higher risk of early PCa.

Subjects and methods

Population

The Gothenburg randomized population-based prostate cancer screening trial was initiated in 1995 and is a branch of the European Randomized Study of Screening for prostate Cancer (ERSPC). As of December 1994, the population register documented 32,298 men born between 1930 and 1944 (age 50–64, median 56 years of age) living in the Gothenburg area. 20,000 men were randomized either to a screening group (n = 10,000) invited for PSA screening every second year or to a control group (n = 10,000) not invited. Using the Regional Cancer Registry, males with prevalent prostate cancer at randomization (n = 56) were excluded as were men who had died or emigrated immediately before randomization (n = 40). This generated a screening group of 9,952 men and a control group of 9,952 men. Participants in the intervention arm were invited for biennial measurements of total PSA (T-PSA) and concurrent free-to-total PSA (F/T-PSA) testing (dual-label DELFIA Prostatus total/free PSA-assay; Perkin-Elmer, Turku, Finland) until they reached an upper age limit, which varied between 67 and 71 with an average of 69 years. Men with an elevated PSA level were offered further clinical assessment, see below. To date, data from eight screening rounds have been completed, analyzed and included in this study. Figure 1 shows the study design and a more complete description of the Gothenburg screening trial has previously been published [12]. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee at Gothenburg University in 1994.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Design

Men with a PSA < 3.0 ng/mL had no further investigations at the time but they were invited for re-screening with PSA testing every second year until they reached the upper age limit. All men with a PSA ≥ 3.0 ng/mL were offered further clinical assessment, including DRE and TRUS-guided biopsies of the prostate. Men with a benign outcome were re-invited for biennial measurement of the PSA and if it was elevated again new biopsies were recommended. Those who were examined on two or more occasions only had their first elevated PSA value and first biopsy result included in this analysis. Non-responders in each screening round were again re-invited for PSA measurement in the next round. Locally advanced PCa was defined as a palpable disease, stage T2b-T4. When comparing cancer detection rates with regard to symptoms (Table 4) we divided all cases into two groups based on their median prostate volume, i.e. < or > 37.8 cm3.

Table 4.

Cancer detection rates and characteristics in men with and without obstructive urinary symptoms

| Voiding symptoms | No voiding symptoms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate volume |

PCa detection rate |

Mean age (SD) |

Md Vol. (IQR) |

Md T- PSA (IQR) |

Md F/T PSA (IQR) |

PCa detection rate |

Mean age (SD) |

Md Vol. (IQR) |

Md T- PSA (IQR) |

Md F/T PSA (IQR) |

| < 37.8 cc N = 1176 |

158/459 34 % |

62.8 4.2 |

30.5 (26.4 – 34.0) |

3.8 (3.3 – 5.0) |

17.0 (12.6 – 23.0) |

262/709 37 % |

62.2 4.5 |

29.1 (24.5 – 33.5) |

3.7 (3.3 – 4.6) |

16.6 (12.3 – 21.9) |

| > 37.8

cc N= 1177 |

96/659 15 %* |

63.1 4.1 |

49.8 (43.5 – 61.4) |

4.0 (3.4 – 5.1) |

22.9 (18.1 – 28.6) |

115/518 22 %* |

63.3 3.8 |

47.0 (41.5–55.4) |

3.9 (3.3 – 4.9) |

21.8 (17.3 – 27.8) |

p< 0.001

Measures

All men with an elevated PSA level who accepted further work-up were asked in conjunction with the doctor’s appointment to complete a study-specific, self-administrated questionnaire. There was one question on obstructive voiding symptoms: “Do you have voiding symptoms in terms of weak stream or difficulty emptying the bladder?” The answers were ranked on an ordinal scale from 1 to 3, i.e. 1 = no symptoms, 2 = minor/moderate symptoms and 3 = major/severe symptoms. Data were dichotomized so that men who answered “2” or “3” were regarded as having voiding symptoms while those who answered “1” were regarded as being asymptomatic. Biopsy findings were classified as “cancer” or “benign outcome”.

Statistical methods

Univariate analysis consisted of the chi-square test and t test, where appropriate. Intergroup differences in mean age, F/T PSA ratio and prostate volume were analyzed using the t test and the Mann-Whitney U test for differences in T-PSA (Table 1 and Table 2). The chi-square test was used for comparison of obstructive voiding symptoms in men with benign biopsies versus those with PCa.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of men with benign PAD versus prostate cancer at first biopsy

| Median (mean, IQR): | Benign PAD N = 1720 |

Cancer N = 633 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.0 (62.6, 59.8 – 65.8) | 64.3 (63.6, 60.8 – 66.8) | < 0.001 |

| Prostate vol., cm3 | 40.0 (43.3, 31.6 – 50.8) | 32.6 (35.2, 26.6 – 41.6) | < 0.001 |

| T-PSA, ng/mL | 3.8 (4.6, 3.3 – 4.6) | 4.1 (6.9, 3.4 – 5.6) | < 0.001 |

| F/T PSA, % | 20.6 (21.7, 15.7 – 26.5) | 16.8 (18.3, 12.0 – 23.3) | < 0.001 |

| Voiding symptoms n, % |

867 (50.4%) | 255 (40.3%) | < 0.001 |

Key: Md = median, IQR= inter quartile range, T-PSA = total prostate-specific antigen

Table 2.

Comparison of asymptomatic men and men with voiding symptoms

| Median (mean, IQR) | Asymptomatic men N = 1230 |

Men with voiding symptoms N = 1123 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.3 (62.8, 59.9 – 66.1) | 63.5 (63.0, 60.1 – 66.2) | 0.099 |

| Prostate volume, mL | 35.3 (37.9, 28.0 – 44.0) | 41.4 (44.8, 32.1 – 52.4) | < 0.001 |

| T-PSA, ng/mL | 3.8 (5.1, 3.3 – 4.7) | 3.9 (5.3, 3.4 – 5.0) | 0.030 |

| F/T PSA, % | 18.8 (20.1, 13.6 – 25.1) | 20.5 (21.6, 15.2 – 26.1) | < 0.001 |

| PCa n, % | 378 (31 %) | 255 (23 %) | < 0.001 |

| Locally advanced tumors* n, % | 36 (9.5 %) | 29 (11.4 %) | 0.473 |

Defined as T2b – T4 tumors

To analyze the impact of the covariates age, prostate volume, T-PSA, F/T PSA ratio, and voiding symptoms, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed and variables with statistically significant impact were retained in the final multivariate model. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression. All variables significantly associated with cancer outcome in the univariate analyses were entered into the multivariate model. Age, T-PSA F/T PSA-ratio and prostate volume were used as continuous variables. Voiding symptoms were set as a dichotomous variable (symptoms present / absent). Odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (95% confidence interval, CI) for all covariates were calculated. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses and tables were created using SPSS® 18.0 statistical software (IBM software, IBM Corporation, 1 New Orchard Road, Armonk, New York 10504-1722, United States).

RESULTS

Of the 7,625 attendees in the screening arm there were 2,590 men who had an elevated PSA level (≥ 3.0 ng/ mL) at least once within the study period (1995 – 2010). Of these, 2,353 men (91%) completed the questionnaire and accepted further clinical work-up, including prostate biopsy, thereby being eligible for further analysis. In this cohort, 633 cancers were detected at first biopsy, and of these, 65 (10%) were locally advanced tumors (T2b-T4). The mean age and the median (Md) T-PSA of all responders was 62.9 years (SD 4.2) and 3.8 ng/mL (interquartile range: IQR 3.3 – 4.8), respectively. Md prostate volume was 37.8 cm3 (IQR; 30.0 – 48.6).

The clinical characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Men with positive biopsy findings (PCa) were slightly younger, had smaller prostates, higher T-PSA and lower F/T PSA ratio (p < 0.001). They also reported a lower frequency of voiding symptoms; 40.4% versus 50.4% (p < 0.001), compared to men with negative biopsies. Table 2 compares asymptomatic men (n = 1,230) and those with voiding symptoms (n = 1,122). In total, 48% of the subjects reported voiding symptoms. There were no statistically significant differences in mean age or the proportion of locally advanced tumors between the two groups. In asymptomatic men the PCa detection rate was significantly higher, 31% versus 23% (p < 0.001).

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, increasing age (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07 – 1.12) and PSA level (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.06 – 1.12) were both significant predictors (p < 0.001) of cancer detection, while prostate volume (OR 0.96, 95%, CI 0.96 – 0.97), F/T PSA-ratio (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96 – 0.99) and the presence of voiding symptoms (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.63 – 0.98) were independently associated with lower odds of detecting PCa in biopsies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the impact of age, prostate volume, T-PSA, F/T PSA-ratio and presence of voiding symptoms on biopsy outcome in men with a T-PSA ≥ 3.0 ng/mL

| Covariate | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.10 | 1.07 – 1.12 | < 0.001 |

| Prostate Vol. (cm3) | 0.96 | 0.96 – 0.97 | < 0.001 |

| T-PSA (ng/mL) | 1.09 | 1.06 – 1.12 | < 0.001 |

| F/T PSA (%) | 0.97 | 0.96 – 0.99 | < 0.001 |

| Voiding symptoms | 0.78 | 0.63 – 0.98 | 0.032 |

Key; OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval

Table 4 shows the PCa detection rates in four groups divided by median prostate volume and symptoms (absent /present). We only found a significant decrease in PCa detection rate in men with large prostate glands (i.e. > 37.8 cm3); 15% in men with voiding symptoms versus 22% in asymptomatic men (p < 0.001). There was no intergroup difference regarding age, T-PSA or F/T PSA ratio between men with small or large prostates regardless of symptoms or not.

Discussion

In this study we found that the absence of voiding symptoms in men with an elevated PSA level (> 3.0 ng/mL) was an independent risk factor for PCa detection. This is to our knowledge the first time in a PCa screening program where all the covariates, age, obstructive voiding symptoms, F/T PSA ratio, T-PSA level, prostate volume and biopsy findings, were considered. The presence of voiding symptoms decreased the risk of a malignant biopsy in a multivariate logistic regression, generating an odds ratio of 0.78.

These results are supported by Catalona et al. who in 1994 reported from a large multicenter clinical trial, comparing the use of DRE and PSA as screening tools for PCa [13]. In this study of 6,630 men, 1,710 had either an abnormal DRE or an elevated T-PSA (> 4.0 ng/mL) and were recommended quadrant prostate biopsies. Of the 1,167 men who underwent biopsy, 264 were found to have PCa. Logistic regression analysis revealed that the absence of urinary symptoms was predictive of the presence of PCa (the adjusted odds ratio for the presence of PCa in symptomatic men was 0.70 (95% CI; 0.51–0.96) compared to 0.78 (95% CI; 0.63–0.98) in our study. However, Catalona et al. did not include F/T PSA ratio or prostate volume in the analysis and potential confounding by age was not taken into consideration. Furthermore, in a study by Collin et al. from 2008 similar findings were reported [14]. Results from 2,467 men with PCa showed that several different urinary symptoms were associated with lower odds of PCa (these odds decreased with increasing severity of individual symptoms). In the HUNT 2 population-based cohort study from 2008, comprising 21,159 Norwegian men, Martin et al. found that the severity of LUTS (as assessed by the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was positively associated with the incidence of localized PCa after a median follow-up of 9.3 years [15]. The incidence of PCa increased with increasing LUTS severity, but no association with advanced cancer was found. However, the authors concluded that PCa does not cause voiding symptoms; rather that the presence of symptoms acted as a screening tier for early PCa detection and over-diagnosis in these men.

Interestingly, in the present study, we could not find any difference in PCa detection rates when comparing men with small prostate glands (< 37.8 cc) with or without voiding symptoms (34% versus 37%). However, asymptomatic men with large prostate volumes (> 37.8 cc) had a significantly higher risk of PCa compared to men with large prostates and urinary symptoms (22% versus 15%). Other studies have shown that when the PSA level is in the 2.0 to 9.0 ng/mL range, a small prostate volume is a strong predictor of cancer detection and that benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and not cancer is the main determinant of PSA elevation. [16,17]. BPH is common among the elderly and men with a benign enlargement of the prostate often have LUTS and an elevated PSA level. This might lead to many “unnecessary” prostate biopsies although these men are at no greater risk of PCa than asymptomatic men.

For many years there is an unresolved discussion about whether a large prostate volume reduces the probability of sampling malignant tissue [18–20]. Previous publications from our group have indicated that men with larger prostates have a lower risk of PCa and that the risk of under-sampling is low. In 2003, Zackrisson et al. [21] looked at 456 men from the Gothenburg screening trial with initially benign biopsies. They were followed for a further four years and after two additional sets of biopsies (total of 18 cores) no patient with a prostate volume of > 70 cm3 turned out to have PCa. However, men with an initial prostate volume < 20 cm3 later either had a PSA normalization or PCa. In concordance, van Leeuwen et al. [22] followed 1,305 men who at initial screening had a negative biopsy result. At follow-up eight years later men with smaller prostates were at greater risk of PCa detection and also of more aggressive cancers, not men with larger prostates, due to under-sampling.

One limitation of the present study is that we did not use a validated questionnaire to assess voiding symptoms. When the Gothenburg screening trial was planned during 1993 and 1994, the IPSS [23] had just recently been presented and was not an established method for evaluating LUTS in Sweden. As longitudinal follow-up has been one of the greatest strengths of this study we chose to continue the original questionnaire instead of changing to the IPSS. However, the prevalence of voiding symptoms according to our questionnaire (48%) is in concordance with several other studies [10,11,24]. Furthermore, we have only investigated the association between voiding symptoms and PCa among men with an elevated PSA level (≥ 3.0 ng / mL), since only these men were invited for prostate biopsies. We are therefore unable to draw any conclusions regarding men with a PSA level < 3.0 ng/mL.

The strength of this study is the high biopsy rate (> 90%) and that it is population based. 77% of all invited men attended at least once. Together with the study size this is likely to be sufficient and should make the results representative for estimating the association between voiding symptoms and PCa detection in the general population. Nevertheless, we do not have information on non-participants who did not attend PSA testing and/or biopsy. A healthy selection bias is probably result of the fact that asymptomatic men are more likely to refuse invitations for PSA tests and prostate examinations. When Avery et al. [25] interviewed men on their decision regarding PSA testing they found that many men believed that the PSA test was unnecessary because of lack of voiding symptoms, perceiving themselves to have a lower PCa risk and therefore declining further biopsies/investigation. If this is the case it would lead to an underestimation of the PCa prevalence in asymptomatic men and thereby increase the importance of our findings.

In summary, we demonstrated that independent predictors of a positive prostate biopsy included age and T-PSA whereas F/T PSA ratio, prostate volume and the presence of obstructive voiding symptoms were inversely related to the detection of PCa. Benign disease causes larger prostate glands that increase the PSA level, whereas PSA elevation in men with smaller prostates is most likely due to the presence of PCa. The results of our study contradict the common belief that voiding symptoms are signs of PCa. We do acknowledge that obstructive voiding symptoms and other LUTS may well be present in men with both BPH and PCa. However, here we found that the absence of symptoms in men with an elevated PSA level was an independent risk factor for detecting PCa in biopsies, which was in contrast to our intuitive assumption and that of others.

In clinical contexts this might be useful when making risk assessments, dealing with patients with PSA elevation and urinary symptoms. In addition, the information about voiding symptoms is an important factor that should be taken into account when constructing clinical nomograms to estimate individual risk factors for PCa [26].

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicate that since voiding symptoms were negatively associated with the risk of PCa, PSA testing and further investigation with prostate biopsies should follow the same guidelines irrespective of symptoms or not. Furthermore, urologists should pay greater attention to the prostate volume when assessing PCa risk.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all members of the Gothenburg randomized population-based prostate cancer-screening trial, particularly Helén Ahlgren and Maria Nyberg for providing administrative support and assistance in data management. We would also like to thank Erik Holmberg for reviewing the methods and the statistical analysis. The study was supported by grants from Göteborgs läkarsällskap (Gothenburg Medical Society) and the Swedish Cancer Society (Grant No. 3792-B96-01XAB), the Sweden America Foundation and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research. None of the funding sources had access to the database or was involved in the collection or management of the data. Nor had they any influence on the writing of this paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Brown CT, O’Flynn E, Van Der Meulen J, Newman S, Mundy AR, Emberton M. The fear of prostate cancer in men with lower urinary tract symptoms: should symptomatic men be screened? BJU Int. 2003;91(1):30–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rai T, Clements A, Bukach C, Shine B, Austoker J, Watson E. What influences men’s decision to have a prostate-specific antigen test? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):365–71. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm033. Epub 2007 Jul 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young JM, Muscatello DJ, Ward JE. Are men with lower urinary tract symptoms at increased risk of prostate cancer? A systematic review and critique of the available evidence. BJU Int. 2000;85(9):1037–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girgis S, Ward JE, Thomson CJ. General practitioners’ perceptions of medicolegal risk. Using case scenarios to assess the potential impact of prostate cancer screening guidelines. Med J Aust. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonler M, Eddy B, Poulsen J. Prostate-specific antigen testing in general practice: a survey among 325 general practitioners in Denmark. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2005;39(1):214–8. doi: 10.1080/00365590510031084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulman CC, Kirby R, Fitzpatrick JM. Awareness of prostate cancer among the general public: findings of an independent international survey. Eur Urol. 2003;44(1):294–302. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socialstyrelsen. Om PSA-prov. 2010 Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/17992/2010-4-10.pdf.

- 8.Thorpe A, Neal D. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Lancet. 2003;361(9366):1359–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, Reilly K, Kopp Z, Herschorn S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50(6):1306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.019. discussion 14-5. Epub 2006 Oct 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasser DB, Carson C, 3rd, Kang JH, Laumann EO. Prevalence of storage and voiding symptoms among men aged 40 years and older in a US population-based study: results from the Male Attitudes Regarding Sexual Health study. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(8):1294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engstrom G. Prevalence, Distress and Quality of Life. 7. Vol. 171. Uppsala: Uppsala University; 2006. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Swedish Male Population; pp. 362–6. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G, Bergdahl S, Khatami A, Lodding P, et al. Mortality results from the Goteborg randomised population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):725–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70146-7. Epub 2010 Jul 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catalona WJ, Richie JP, Ahmann FR, Hudson MA, Scardino PT, Flanigan RC, et al. Comparison of digital rectal examination and serum prostate specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: results of a multicenter clinical trial of 6,630 men. J Urol. 1994;151(5):1283–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collin SM, Metcalfe C, Donovan J, Lane JA, Davis M, Neal D, et al. Associations of lower urinary tract symptoms with prostate-specific antigen levels, and screen-detected localized and advanced prostate cancer: a case-control study nested within the UK population-based ProtecT (Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment) study. BJU Int. 2008;102(10):1400–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07817.x. Epub 2008 Jun 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin RM, Vatten L, Gunnell D, Romundstad P, Nilsen TI. Lower urinary tract symptoms and risk of prostate cancer: the HUNT 2 Cohort, Norway. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(8):1924–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Azab R, Toi A, Lockwood G, Kulkarni GS, Fleshner N. Prostate volume is strongest predictor of cancer diagnosis at transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy with prostate-specific antigen values between 2.0 and 9.0 ng/mL. Urology. 2007;69(1):103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamey TA, Johnstone IM, McNeal JE, Lu AY, Yemoto CM. Preoperative serum prostate specific antigen levels between 2 and 22 ng./ml. correlate poorly with post-radical prostatectomy cancer morphology: prostate specific antigen cure rates appear constant between 2 and 9 ng./ml. J Urol. 2002;167(1):103–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsubara A, Yasumoto H, Teishima J, Seki M, Mita K, Hasegawa Y, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and risk of prostate cancer in Japanese men. Int J Urol. 2006;13(8):1098–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter CR, Kim J. Low AUA symptom score independently predicts positive prostate needle biopsy: results from a racially diverse series of 411 patients. Urology. 2004;63(1):90–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djavan B, Zlotta AR, Ekane S, Remzi M, Kramer G, Roumeguere T, et al. Is one set of sextant biopsies enough to rule out prostate Cancer? Influence of transition and total prostate volumes on prostate cancer yield. Eur Urol. 2000;38(2):218–24. doi: 10.1159/000020282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zackrisson B, Aus G, Lilja H, Lodding P, Pihl CG, Hugosson J. Follow-up of men with elevated prostate-specific antigen and one set of benign biopsies at prostate cancer screening. Eur Urol. 2003;43(4):327–32. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Leeuwen P, van den Bergh R, Wolters T, Schroder F, Roobol M. Screening: should more biopsies be taken in larger prostates? BJU Int. 2009;104(7):919–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08627.x. Epub 2009 May 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992 Nov;148(5):1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen BL. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sexual function in both sexes. Eur Urol. 2004;46(2):229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avery KN, Blazeby JM, Lane JA, Neal DE, Hamdy FC, Donovan JL. Decision-making about PSA testing and prostate biopsies: a qualitative study embedded in a primary care randomised trial. Eur Urol. 2008;53(6):1186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.07.040. Epub 2007 Aug 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam RK, Toi A, Klotz LH, Trachtenberg J, Jewett MA, Appu S, et al. Assessing individual risk for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3582–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]