Abstract

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are a recognized model for studying the pathogenesis of cognitive deficits and the mechanisms underlying behavioral impairments, including the consequences of increased oxidative stress within the brain. The lipophilic antioxidant vitamin E (α-tocopherol; VitE) has an established role in neurological health and cognitive function, but the biological rationale for this action remains unknown. In the present study, we investigated behavioral perturbations due to chronic VitE deficiency in adult zebrafish fed from 45 days to 18-months of age diets that were either VitE-deficient (E−) or sufficient (E+). We hypothesized that E− zebrafish would display cognitive impairments associated with elevated lipid peroxidation and metabolic disruptions in the brain. Quantified VitE levels at 18-months in E− brains (5.7 ± 0.1 nmol/g tissue) were ~22-times lower than in E+ (122.8 ± 1.1; n= 10/group). Using assays of both associative (avoidance conditioning) and non-associative (habituation) learning, we found E− vs E+ fish were learning impaired. These functional deficits occurred concomitantly with the following observations in adult E− brains: decreased concentrations of and increased peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (especially docosahexaenoic acid, DHA), altered brain phospholipid and lysophospholipid composition, as well as perturbed energy (glucose/ketone), phosphatidylcholine and choline/methyl-donor metabolism. Collectively, these data suggest that chronic VitE deficiency leads to neurological dysfunction through multiple mechanisms that become dysregulated secondary to VitE deficiency. Apparently, the E− animals alter their metabolism to compensate for the VitE deficiency, but these compensatory mechanisms are insufficient to maintain cognitive function.

Keywords: α-tocopherol, choline, dementia, docosahexaenoic acid, lysophospholipids, ketones, phospholipids

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive impairment, or cognitive decline, a noticeable and measurable decline in cognitive abilities (e.g. memory and learning) that exceeds those attributed to normal aging, represents an early symptom of neurodegeneration and increased risk for progression to more severe dementias, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. Cognitive impairment and ensuing dementia are increasingly pressing public health concerns as the global population ages [2]. While the complex etiology of these conditions remains an area of active investigation, oxidative damage has been implicated as a primary factor in neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis [3]. The vertebrate brain is especially enriched in long-chain polyunsaturated lipids, such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6 n-3) [4]; therefore, lipid peroxidation is a likely contributor to neuropathology [5]. Zebrafish are a recognized model for studying the pathogenesis of cognitive deficits [6] and the mechanisms underlying behavioral impairments, including the consequences of increased oxidative stressors within the brain [7].

The lipophilic antioxidant vitamin E (α-tocopherol; VitE) has an established role in neurological health and mitigation of oxidative stress. Specifically, VitE’s biological half-life in the brain is slower than in other tissues [8,9], which results from tissue-specific mechanisms. Brain VitE is actively retained; the mechanism is likely the α-tocopherol transfer protein (α-TTP), which has been shown to traffic α-tocopherol within the brain [10]. Cerebellar α-TTP expression is regulated both by oxidative stress and VitE status [11,12]. For example, α-TTP is markedly elevated in brain samples from human patients afflicted with neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD [13], thus, emphasizing the key role VitE plays in brain antioxidant protection.

The outcome of prolonged VitE deficiency in humans is spinocerebellar degeneration, which manifests as a progressive sensory neuropathy and ataxia [14]. In addition, studies in mice show that VitE deficiency causes cognitive decline, which is associated with increased lipid peroxidation within the brain [15,16]. However, results from human trials examining the efficacy of VitE supplementation for the treatment of dementia have been inconclusive. Findings in humans [17,18] and in mice [19,20] collectively suggest VitE is necessary for preserving cognitive function, but the specific mechanism(s) underlying such a role remain unknown. Therefore, to elucidate VitE’s role in brain metabolism, we sought to answer the question: how does chronic VitE deficiency contribute to cognitive decline?

We reported previously that 12-month-old adult VitE-deficient (E−) zebrafish exhibit reduced swimming behaviors compared with VitE-sufficient (E+) zebrafish, indicating neuropathy and/or myopathy in the E− fish [21]. In subsequent studies, we showed that concomitant with combined VitE and vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiencies, E− fish suffer degenerative myopathy, which decreased their responsiveness to behavioral (startle response) assays [22]. These combined antioxidant deficiencies precluded assessment of neurological and cognitive consequences resulting solely from VitE deficiency. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the behavioral perturbations of isolated VitE deficiency in adult E− and E+ zebrafish fed diets with adequate ascorbic acid [22,23]. We hypothesized that E− adult zebrafish would display significant cognitive impairments associated with elevated brain lipid peroxidation and, potentially, additional metabolic disruptions, as we reported in VitE-deficient zebrafish embryos [24,25].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Reagents used for lipidomic analyses included: methanol and ultra-pure water (LC-MS grade, EMD Millipore, Gibbstown, NJ), formic acid, acetic acid (Optima LC/MS grade; Fisher Chemical, Pittsburgh, PA), and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, TCI America; Portland, OR), as well as zirconium oxide beads (Next Advance; Averill Park, NY). 1,2-ditridecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DT-PC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL) and used without further purification. Deuterium (d) labeled internal standards docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-d5, arachidonic acid (ARA)-d8, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)-d5, linoleic acid (LA)-d4, α-linolenic acid (ALA)-d14, 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE)-d8 and 9-hydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid (9(S)-HODE)-d4 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) were used for quantification of total and free fatty acids and oxidized DHA derivatives, respectively.

Zebrafish Husbandry

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Oregon State University approved this protocol (ACUP Numbers: 4344, 4706). Tropical 5D strain zebrafish (Danio rerio) were housed in the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory. Adults were kept at standard laboratory conditions of 28°C on a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod in fish water (FW) consisting of reverse osmosis water supplemented with a commercially available salt (Instant Ocean®) to create a salinity of 600 microsiemens. Sodium bicarbonate was added as needed to adjust the pH to 7.4. At two-months of age, adult zebrafish were randomly allocated to one of two diet groups, VitE deficient (E−) or sufficient (E+), and fed one of the defined diets for the duration of the study. The defined diets, which contained only fatty acids with 18 or fewer carbons and 2 or 3 double bonds were prepared with the vitamin C source as StayC (500 mg/kg, Argent Chemical Laboratories Inc., Redmond, WA) and without (E−) or with added α-tocopherol (E+, 500 mg RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate/kg diet, ADM, Decatur, IL), as described previously [21,25].

Every effort was made to minimize suffering of the fish. Prior to lipidomics sampling at 18-months of age, all fish were euthanized by cold exposure, then snap-frozen whole in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyses.

Tocopherol and ascorbic acid analyses

Using high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD), α-tocopherol was measured in diet samples, brain and muscle tissue, as described previously [26]. Brain weights were not significantly different between groups (n=10/diet; E− 2.3 ± 0.2 vs. E+ 2.4 ± 0.2 mg). Ascorbic acid content in diet and muscle tissue was measured using HPLC-ECD as previously described [27]. Measured α-tocopherol concentrations in the E− and E+ diets were 0.45 ± 0.01 and 369 ± 2 mg/kg (n= 3 replicate samples measured for each diet), respectively. Vitamin C concentrations were 148 ±10 mg ascorbic acid/kg diet, a level that is adequate for the zebrafish [22].

Shuttle-box testing

Associative learning and memory in adult zebrafish, was performed using custom-build shuttle-boxes, as described [28] with modifications [29]. Briefly, the protocol conditioned zebrafish to leave the dark side (“reject side”) of the shuttle-box and swim into the compartment with blue light (“accept side”). Following a 10-minute acclimation period (in white light) prior to beginning each trial, a single adult zebrafish was allotted 8 seconds to “seek” the accept side to avoid a moderate shock; if it did not move from the reject side, a 16 second shock period was initiated in which a moderate pulse of ~0.7V/cm was delivered for a duration of 500 milliseconds. A total of 30 trials per fish were performed, but if a fish failed to swim to the lighted chamber and received a shock for eight consecutive trials, then it was removed from the study for ethical reasons and considered a “fault-out”. The number of fault-out fish was not different between E− and E+ groups; these fish were not included in subsequent analysis, summarized below.

Startle response testing

Assessment of non-associative learning (habituation) was performed using an updated modification of the startle response assay as outlined [22]. In brief, the experimental set-up consisted of 8 side-by-side tanks with an observation window facing an LED screen. Three sides of each tank were masked opaque white to prevent interactions between fish. All tanks were filled with 750 mL of water. An IP surveillance camera (Q-SeeHD) with infrared sensitivity was placed above the tanks to allow for top view video recording. The setup was placed over a custom LED lightbox with solenoid tap units directly below each tank. A total of 64 naïve zebrafish (32/diet group) were gently netted into individual tanks. The assay consisted of a 10-minute acclimation period, followed by three startle stimuli (one every 5 minutes). Swim motion was recorded throughout using Media Recorder software and analyzed using Noldus Ethovision 11.5. For each video, a tracking arena was defined by size and position. The fish were tracked at 25 frames per second and total distance swam (in centimeters) and velocity for one minute; 10 second bins were reported for acclimation and startle phases, respectively.

Extraction, LC-MS/MS, and data analysis

For untargeted lipidomics, the brains from E− and E+ zebrafish (n= 5 brains/group) were dissected, weighed, then extracted individually in solvent (300 μL, 25:10:65 v/v/v methylene chloride: isopropanol: methanol, with 50 μg/mL butylated hydroxytoluene [BHT]) with added internal standard (0.5 μg/μL, 1,2-ditridecanoyl-snglycero-3-phosphocholine [DT-PC, PC 26:0] in methanol) for analyses by LC-MS/MS, as described [24,25]. Chromatography was performed with a Shimadzu Nexera system (Shimadzu; Columbia, MD, USA) coupled to a high-resolution hybrid quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (TripleTOF® 5600; SCIEX; Framingham, MA, USA).

E− and E+ brains (n= 2 brains/sample; four replicate samples per group) were extracted for metabolomics analyses as described [24]. Two different LC analyses using reverse phase and HILIC columns were used, as previously described [24], using the TripleTOF® 5600.

Sample preparation, extraction, and LC-MS/MS analyses of total or free DHA, EPA, ARA, LA fatty acids; and oxidized lipid derivatives

Analyses of brain total fatty acids (specifically: docosahexaenoic (DHA), eicosapentaenoic (EPA), arachidonic (ARA), alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), and linoleic (LA)) from E− and E+ fish (n= 10/diet) were performed following saponification, as described previously [24] with the use of 10 μL internal standard mixture containing d-labeled fatty acids [DHA-d5 (1.0 μg/mL), EPA-d5 (1.0 μg/mL), ARA-d8 (2.0 μg/mL), ALA-d14 (1.0 μg/mL) and LA-d4 (2.0 μg/mL)].

Extracts for analyses of free fatty acids or oxidized lipids were prepared as described for lipidomics samples [24] with the following adjustments: individual E− and E+ brains were homogenized with extraction solvent (290 μL, 80:20 v/v methanol:water with 50 μg/mL BHT) with 10 μL per sample of internal standard mixture containing [DHA-d5 (1.0 μg/mL), EPA-d5 (1.0 μg/mL), ARA-d8 (2.0 μg/mL), ALA-d14 (1.0 μg/mL), LA-d4 (2.0 μg/mL), 5-hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE-d8, 1.0 μg/mL) and 9-hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE-d4, 1.0 μg/mL)]. Analyses were performed as previously described [24], using the TripleTOF® 5600.

Statistical analyses

For shuttle-box assays, numerous parameters previously described in Truong et al. [28] were collected, including “Time to a Side (seconds)”, the time required by the fish to make the initial crossing from the reject to the accept side and the number of times a fish returned to the dark (the reject chamber) after having escaped to the lighted, accept chamber (“Returns to Dark”). The statistical methods remained the same as described previously [28] using custom R scripts. Briefly, data was acquired for individual fish in each diet group (n = 37 E− and n = 34 E+), with responses fit to a linear regression to determine if a fish learned. To calculate an overall learning rate (slope) for each diet group, the average response of all E− and E+ fish, respectively, for each trial was taken and used to model a group linear regression. A student’s t-test (p<0.05) was used to calculate statistical significance between E− and E+ learning rates.

To analyze startle response data, all tracked data files were imported into R software (R Developmental Core Team 2014, http://www.R-project.org) and analyzed using custom-made scripts to generate mean ± SEM outputs for tracked movement over each trial interval (both Acclimation and Tap response intervals, respectively). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Additional statistical analyses (e.g. 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s or Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, as recommended by the software) were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Lipidomics data processing was performed as described [23,25]. Student’s t-tests (Excel, Microsoft) were used to compare the two VitE groups with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Targeted metabolomics data processing was performed as described previously [24]. To ensure the stability and repeatability of the LC–MS system, quality control (QC) samples (n=4), which were generated by pooling 10 μL aliquots from each brain extract, were analyzed with the brain samples. Peak intensities for each individual metabolic feature were normalized using the corresponding mean QC sample (n=4) intensity for that feature to balance any differences in intensities that may have arisen during sample preparation, as described [30]. Brain weights were not different between groups; response values for metabolomics were not corrected for brain weights, other samples were corrected as indicated in the figure legends. The Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparisons was used to compare normalized metabolite/analyte intensity values (reported as “responses”) between the two diet groups for metabolites (n ≤ 12 metabolites per pathway/category analyses) (Supplementary Table 1) with statistical significance set at p< 0.05. All statistical analyses for lipidomics and metabolomics were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Quantification of total and free fatty acids, and oxidized lipids was performed using MutliQuant Software version 3.0.2 (SCIEX), as performed previously [24]. Statistical analyses were performed as for lipidomics/metabolomics (above).

Data are presented as means ± SEM.

RESULTS

Adult behavior and cognitive function

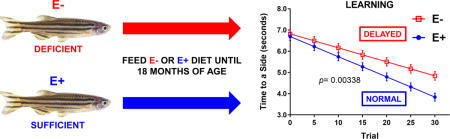

We first investigated the effects of chronic VitE deficiency on cognitive outcomes in adult E− and E+ zebrafish. To assess learning, we utilized the shuttle-box active avoidance assay, a modification of the protocol described [28,29], in which 12-month-old adult E− and E+ zebrafish were trained to actively “shuttle” from a dark, “unsafe” chamber into a lighted, “safe” chamber to avoid an aversive stimulus (mild electrical shock). Grouped linear regressions of the “Time to a Side” parameter (the cumulative time per trial that a fish required to shuttle to the lighted chamber, in seconds) revealed that over the 30-trial testing phase, E− adults took significantly longer to swim to safety than E+ adults (Figure 1). These findings suggest an impaired ability to associate presentation of the discriminative/operant light stimulus with safety (i.e. avoidance of the shock stimulus). Similar analyses using the “Returns to Dark” parameter (the number of times within a trial that a fish returns to the dark chamber and receives a shock after having shuttled to the lighted chamber), as another metric of learning ability, showed that E− adults returned to the unsafe chamber significantly more than did E+ fish (p =0.0048, E− 2.87 ± 0.35 vs. E+ 1.21 ± 0.29 Returns to Dark, over 30 trials). Thus, both parameters suggest impaired cognitive function.

Figure 1. E− adults were learning impaired when compared to E+ adults.

Grouped linear regressions of the time required (“Time to a Side”, in seconds) for an individual fish to decide to swim to the lighted, “safe” chamber in the E− (n= 37) vs. E+ (n= 34) diet conditions. By the 30th trial, E− adults took significantly longer to associate the light stimulus with safety, indicating impaired learning. For each diet condition, the data were fit using group linear regression models, which allowed observance of variance and reduced the sensitivity to outliers. E− vs. E+ learning rates were compared using a student’s t test to calculate statistical significance (p< 0.05).

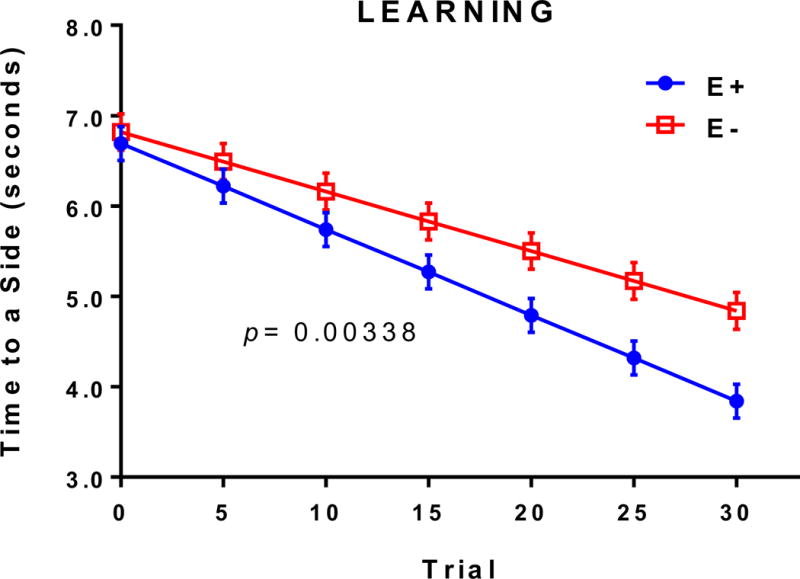

To further assess cognitive function, we performed non-associative learning (habituation) evaluations in which a startle response (increased swimming following a loud noise) was measured following a series of tap-stimuli. In this assay, the startle response was expected to decrease with successive taps as the animal habituates to the stimulus; that is, learns that the noise is not harmful. Baseline swimming activity was the same in both E− and E+ adults, as was the respective groups’ startle response to the first tap (Figure 2). However, while the E+ adults mounted sequentially lower startle responses to later tap stimuli, indicating a successful ability to habituate/learn, E− adults did not (Figure 2). These data indicate that the E− fish did not suffer compromised locomotion; therefore, outcomes from both shuttle-box and habituation assays suggest reduced learning ability and cognitive impairment associated with chronic VitE deficiency.

Figure 2. E− adults had a compromised habituation (startle) response compared to E+ adults.

A total of 64 naïve E− and E+ zebrafish (n= 32/diet condition) were tracked at 25 frames/sec for total distance swam (cm) and velocity over one-minute intervals during acclimation (Baseline) and following each tap stimulus, shown above as mean distances ± SEM. During the 10-minute acclimation period prior to the first startle tap, E− and E+ fish exhibited the same amount of swimming activity. In response to the initial tap (TAP 1), both E+ and E− zebrafish mounted a similar swim response, but E− zebrafish mounted nearly the same magnitude of response to all three startles (taps), indicating failure to habituate to the stimulus (Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test for multiple comparisons; overall p <0.0001 for Diet × Tap interaction; ****p <0.0001 at indicated Taps).

VitE status, lipid peroxidation, and lipidomics assessments

We hypothesized that the E− adults’ behavioral perturbations were likely related to their decreased brain VitE contents. Quantified brain α-tocopherol concentrations at 18 months in E− (5.7 ± 0.1 nmol/g) were ~20-times lower than in E+ adult brains (122.8 ± 1.1 pmol/mg; n= 10/group). Since both cognitive function tests described above require adequate swimming abilities, the muscle antioxidant status was assessed. Muscle α-tocopherol concentrations in the E− and E+ muscle (n= 10/group) were 1.3 ± 0.1 and 114.8 ± 0.9 nmol/g wet weight, respectively. Previously, we observed impaired swimming ability in E− adults, which were fed diets that were both VitE deficient and inadequate in vitamin C [22]. However, in the present study muscle tissue ascorbic acid concentrations were similar between groups (n= 4/group, E− 84.9 ± 0.3 nmol/g vs E+ 84.7 ± 0.3 nmol/g muscle). These data confirm that the vitamin C status was adequate and that the impaired cognitive responses are not due to limited swimming abilities.

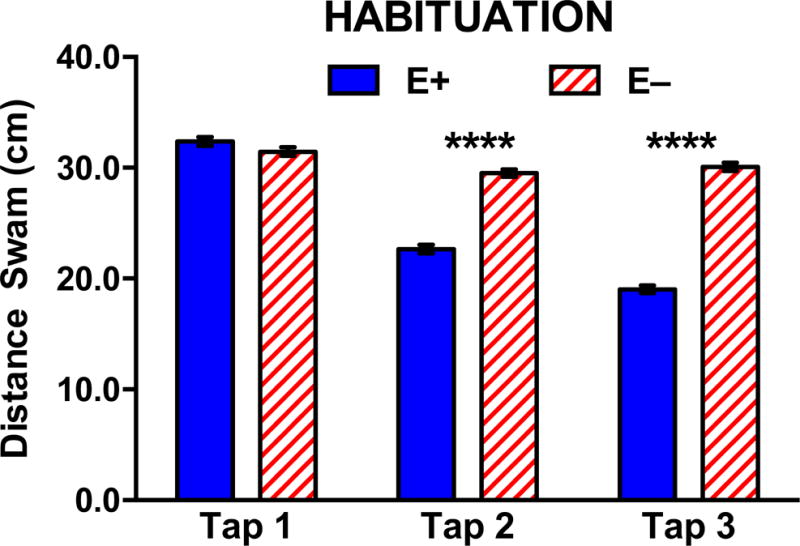

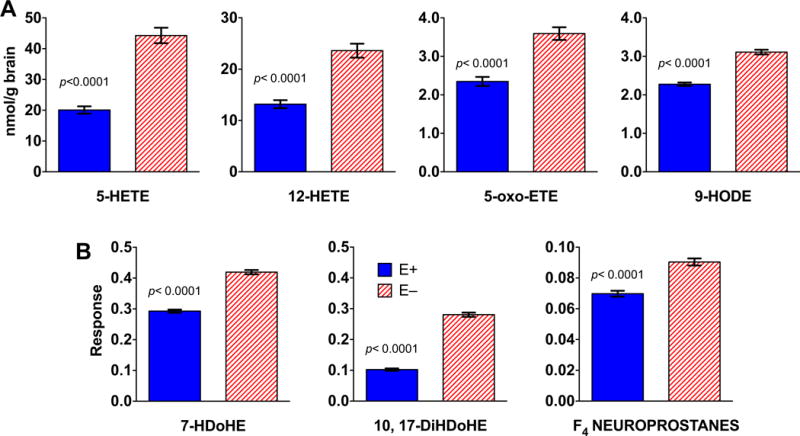

Given (a) VitE’s role as a lipophilic antioxidant [31], and (b) the brain’s high concentrations of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially DHA [32], we quantified total and unesterified (free) levels of n-3 and n-6 PUFAs in E− vs. E+ brains (Figure 3). The greatest decreases were found for total DHA and arachidonic acid (ARA; 20:4 n-6), which both were depleted in the E− fish to approximately half of the concentrations in the E+ (Figure 3A); free forms of DHA and ARA were also depleted (Figure 3B). E− vs E+ brains contained significantly higher amounts of oxidation products from both n-6 (5-HETE, 12-HETE, 5-oxo-ETE, and 9-HODE, Figure 4A) and n-3 (7-HDoHE and 10,17 DiHDoHE Figure 4B) fatty acids, including F4-neuroprostanes, which are autoxidized DHA-derivatives. These data demonstrate that long-term VitE deficiency led to depletion particularly of DHA and ARA and to enhanced lipid peroxidation.

Figure 3. Quantified levels of total and unesterified (free) fatty acids in E− vs. E+ adult brains.

Individual fatty acids were quantified from area counts obtained with the TripleTOF® 5600 using responses for matching deuterium-labeled internal standards (DHA-d5, EPA-d5, ARA-d8, ALA-d14, LA-d4) and respective brain weights (n= 10 samples/diet), as described in methods. A) Saponified (total) and B) only extracted (free) fatty acids are shown; μmol/g, means ± SEM; p-values are indicated as **<0.005, ***<0.001, **** <0.0001 from unpaired Student’s t-tests. Abbreviations: ALA (alpha-linolenic acid); ARA (arachidonic acid); DHA (docosahexaenoic acid); EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid); LA (linoleic acid).

Figure 4. Oxidized fatty acids were elevated in E− compared to E+ brains.

Oxidized fatty acids are shown from adult E− and E+ zebrafish brains (n= 5/group). A) Shown are pmol/mg brain (means ± SEM); area counts from the TripleTOF® 5600 were quantified using internal standards (5-HETE-d8 for HETEs and 5-oxo-ETE; 9-HODE-d4 for 9-HODE) and corrected for each respective brain weight. B) Responses shown are equal to the counts normalized by the QC counts and corrected for each respective brain weight; standards were not available for these samples. Significant differences (p <0.05) were determined for each lipid using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test. Abbreviations: 5-HETE (5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid); 12-HETE (12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid); 5-oxo-EET (5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid); 9-HODE (9-hydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid); 7-HDoHE (7-hydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid); 10, 17-DiHDoHE (10, 17-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoic acid) and F4-neuroprostanes (Note: the approach used does not permit unequivocal identification of the specific F4-neuroprostane isomer(s); we did confirm that the metabolite mass, retention time, and ms/ms fragmentation pattern matched those of the 4-series F4-neuroprostanes, e.g. high-intensity [M+H] precursor ion m/z at 343.227).

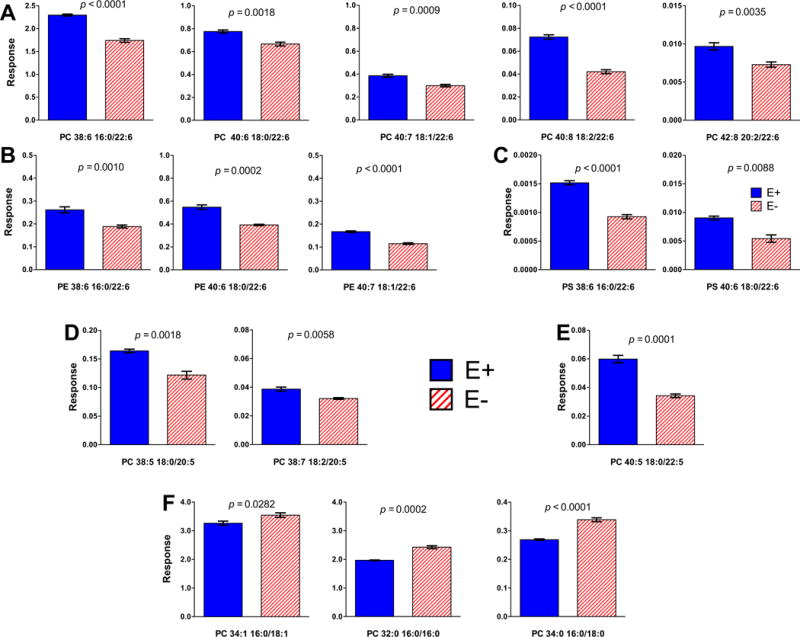

Previously, we reported using lipidomics analyses of brains from 12-month-old fish that VitE deficiency specifically depleted four phospholipids containing DHA [23]. Herein we show brains from 18-month-old E− vs E+ fish were lower in 13 different PLs (Figure 5). E− brains contained less DHA-phosphatidyl choline (DHA-PC, Figure 5A), DHA-phosphatidyl ethanolamine (DHA-PE, Figure 5B) and DHA-phosphatidyl serine (DHA-PS, Figure 5C); and less of two PC containing EPA (EPA-PC, Figure 5D) and one PC containing docosapentaenoic acid (DPA-PC, Figure 5E). Moreover, we show herein for the first time that E− brains contained more highly-saturated PLs than did E+ brains (Figure 5F), suggesting that damaged (oxidized) unsaturated fatty-acyl chains were replaced with saturated ones. Lower levels of 12 lyso-phospholipids (lysoPLs), including lysophosphatidylcholine containing DHA (DHA-LysoPC 22:6), the preferred form of DHA for uptake into the brain [33–35], also were evident in E− vs E+ brains (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Specific DHA-PLs were lower in E− compared with E+ brains.

Statistical differences shown between PL identified using lipidomics (and outputs from the TripleTOF® 5600) from extracts of brains of E− vs E+ (mean ± SEM, n= 5/diet group) were determined using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test (p < 0.05). E− brains contained significantly less of certain specific PL, which are indicated by 2-letter abbreviations and the number of carbons:double bonds, followed by each of the fatty acids separated by a slash (/) and indicated by number of carbons:double bonds; A) phosphatidyl choline (PC), B) phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE), C) phosphatidyl-serine (PS), D) PC containing EPA (20:5) and E) PC containing docosapentaenoic (DPA, 22:5). F) E− brains contained significantly more of certain specific PC containing saturated [palmitic (16:0), stearic (18:0)] and monounsaturated [oleic (18:1)] fatty acids. Responses shown are equal to the counts normalized by the internal standard (PC 26) counts and corrected for each respective brain weight. Statistical differences were determined using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

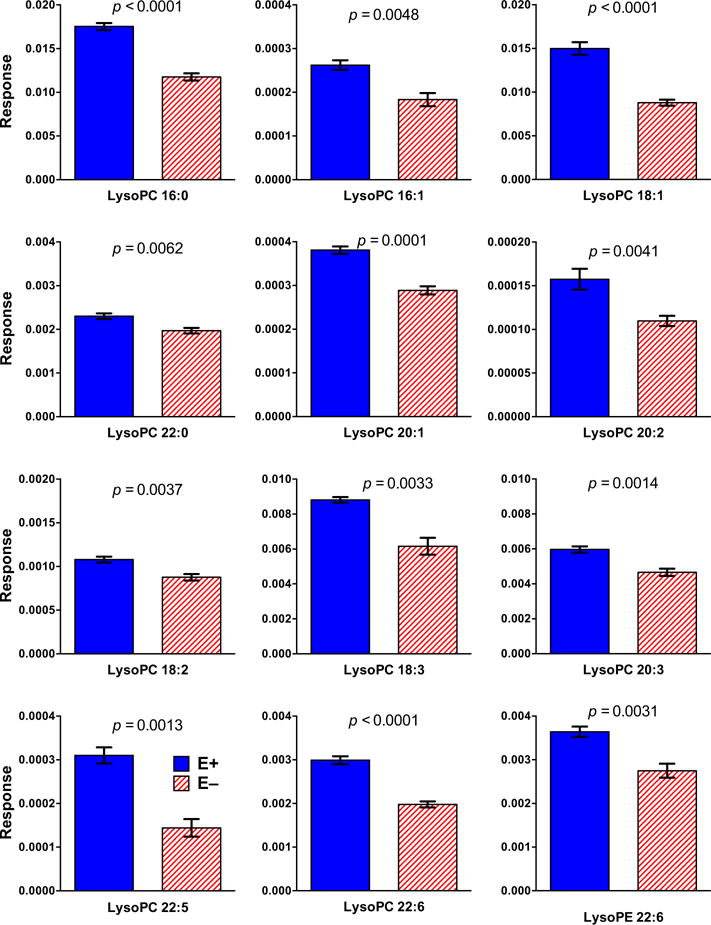

Figure 6. E− zebrafish brains contained significantly less of 11 lyso-PCs and 1 lyso-PE compared to E+ brains.

E− vs E+ brains contained significantly less of specific LysoPLs (mean ± SEM, n= 5/diet group), which are indicated by lyso-2-letter abbreviations (PC, phosphatidyl choline; PE, phosphatidyl ethanolamine) and the fatty acid indicated by the number of carbons:double bonds [palmitic (16:0), palmitoleic (16:1), oleic (18:1), linoleic (18:2), alpha-linolenic (18:3), docosanoic (22:0), eicosenoic (20:1), eicosadienoic (20:2), eicosatrienoic (20:3), docosapentaenoic (22:5), and docosahexaenoic (22:6)]. MS responses (area counts from the TripleTOF® 5600) were used for relative quantification. Responses shown are equal to the counts normalized by the internal standard (PC 26) counts and corrected for each respective brain weight. Statistical differences were determined using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

Metabolomic assessment of energy-metabolism

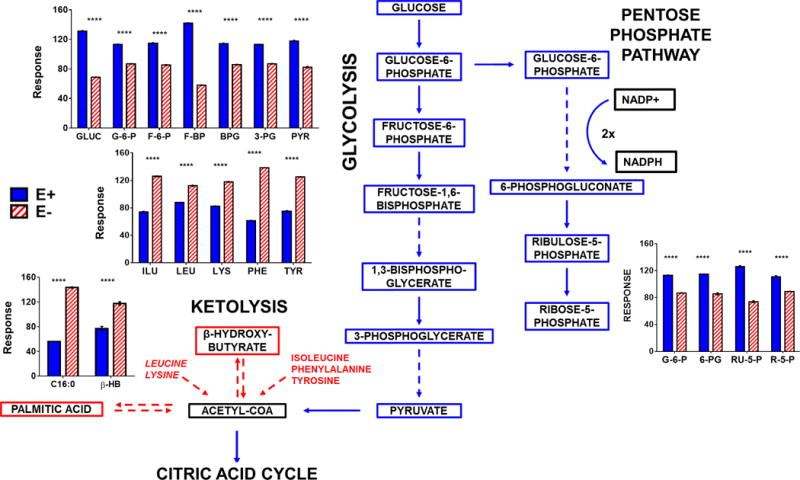

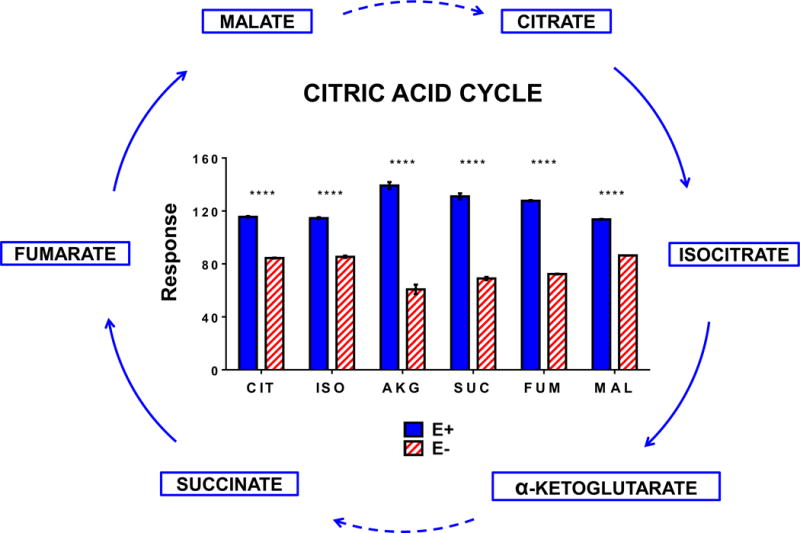

Previously, we reported in E− zebrafish embryos that energy metabolism was severely dysregulated [24]. Therefore, we performed metabolomics analyses of E− vs E+ brains, which revealed decreases in glucose and glycolytic intermediates, as well as reduced levels of pentose-phosphate pathway intermediates (Figure 7). Thus, VitE deficiency-induced a dysregulation of glucose metabolism both for energy production and for generation of reducing equivalents (e.g. NADPH) to replenish and maintain the redox equilibrium. Interestingly, E− vs E+ brains contained higher levels of the ketone body, β-hydroxy-butyrate. Additionally, ketogenic amino acids (especially lysine and leucine) and palmitic acid (16:0), all of which may be utilized for ketone synthesis, were elevated in E− brains (Figure 7). Further, citric acid cycle intermediate concentrations were uniformly lower in E− vs E+ brains (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Cytosolic energy metabolism pathways in the brain were perturbed in E− adults.

The data shown in bar charts compare levels of individual metabolites included in the outlined metabolic pathway diagram (left). Boxes shown in Red (increased in E−) or Blue (increased in E+) represent metabolites that were higher (P<0.05) in E− or E+, respectively. Black boxes indicate relative levels of a given metabolite are not shown in the bar charts in the figure. Solid lines indicate direct reactions and dashed lines denote several reaction steps between metabolites. MS responses (area counts from the TripleTOF® 5600) were used for relative quantification; responses shown are equal to the counts normalized to the QC samples; brain weights were not significantly different between groups, but values were not corrected for brain weights. Statistical differences were determined using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: GLUC, glucose; G-6-P glucose-6-phosphate; F-6-P, fructose-6-phosphate; F-1,6-BP, fructose-1,6,-bisphosphate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PYR, pyruvate; 6-PG, 6-phosphogluconate; RU-5-P, ribulose-5-phosphate; R-5-P, ribose-5-phosphate; β-HB, β-hydroxy-butyrate; C16:0, palmitic acid.

Figure 8. Mitochondrial energy metabolism was decreased in E− compared to E+ adult brains.

The data shown in bar charts compare levels of individual metabolites included in the outlined metabolic pathway diagram (left). Boxes shown in Blue represent metabolites that were higher in E+ compared to E-. Solid lines indicate direct reactions and dashed lines denote several reaction steps between metabolites. MS responses (area counts from the TripleTOF® 5600) were used for relative quantification; responses shown are equal to the counts normalized to the QC samples; brain weights were not significantly different between groups, but values were not corrected for brain weights. Statistical differences were determined using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: CIT, citrate; ISO, isocitrate; AKG, α-ketoglutarate; SUC, succinate, FUM, fumarate; MAL, malate.

Metabolomics assessments of phospholipid and choline metabolites

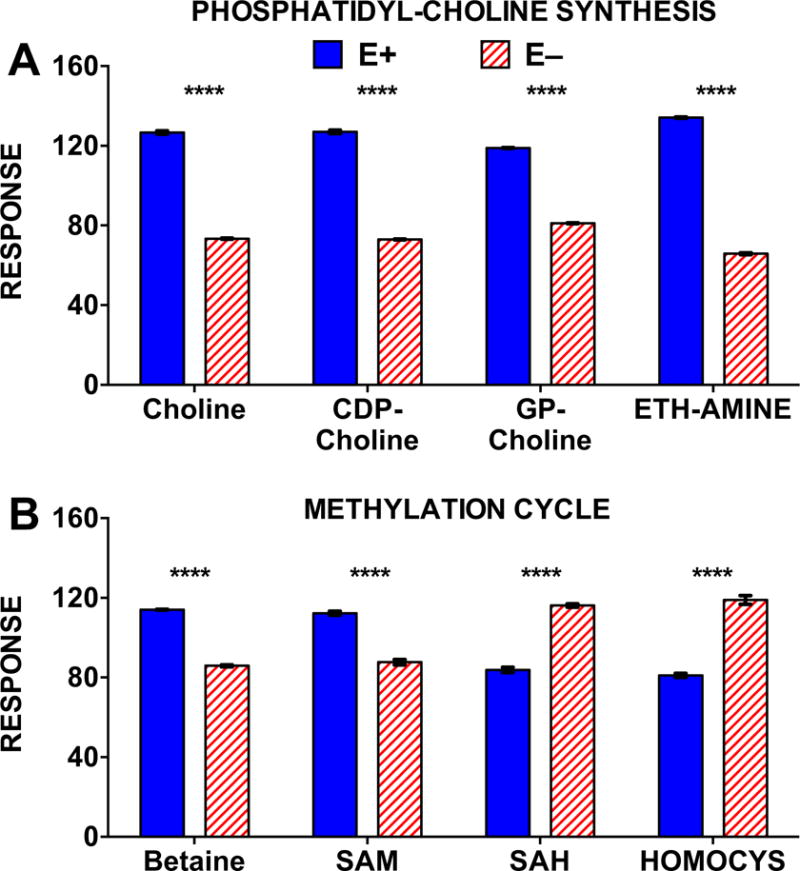

Given the disruption of PL and LPL composition (Figures 4–6) and of cellular energy metabolism (Figures 7 and 8) observed in the E− brains, we also investigated whether VitE deficiency perturbed other metabolic pathways; particularly those related to choline, since PC was the PL most affected by VitE deficiency. Choline and other CDP-choline pathway metabolites, as well as ethanolamine (used for PE and subsequent PC synthesis), were altered in E− vs E+ brains (Figure 9A). VitE deficiency was also associated with decreases in betaine and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and we found parallel increases in oxidized methylation cycle metabolites, S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) and homocysteine (Figure 9B).

Figure 9. Choline and choline-dependent methyl-donors and phospholipid synthesis intermediates in the brain were altered in E− compared to E+ adults.

Metabolomics results for A) CDP-choline metabolism and B) choline-dependent methylation pathways in E− vs. E+ adult zebrafish brains (n= 2 brains/sample; 4 replicates per group). MS responses (area counts from the TripleTOF® 5600) were used for relative quantification; responses shown are equal to the counts normalized to the QC samples; brain weights were not significantly different between groups, but values were not corrected for brain weights. Statistical differences were determined using logarithmically transformed data and an unpaired student’s t-test (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: CDP-choline, cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine; GP-choline, glycerophosphocholine; ETH-AMINE, ethanolamine. SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; HOMOCYS, homocysteine.

DISCUSSION

Chronic VitE deficiency impairs both associative (avoidance conditioning) and non-associative (habituation) learning in adult zebrafish. These functional deficits in adult E− brains occur concomitantly with decreased PUFA concentrations and their increased peroxidation, as well as with altered brain PL and lysoPL compositions, and perturbed energy (glucose, ketone), choline and methyl-donor metabolites. Remarkably, although VitE deficiency leads to major alterations in lipid and energy metabolites, apparently resulting from metabolic responses that allow the animal to function in the face of increased lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage, these changes are insufficient to prevent major deficits in cognitive function.

We utilized complementary behavioral assays to show that VitE deficiency specifically compromised cognition, rather than perception and/or locomotion [21,22]. The shuttle-box assay is widely employed as a paradigm to evaluate learning in zebrafish via avoidance conditioning [28]. The fish must perceive the light and swim towards the light to escape receiving a shock. E− fish responded to the light stimulus by directly (rather than aimlessly) swimming into the illuminated chamber – albeit less promptly than E+ fish. Thus, the E− group perceived the light, suggesting that the fish can see, but may have either impaired cognition or impaired swimming ability. To address the possibility of compromised locomotion, we next performed a habituation (startle-response) assay to determine if the E− adult’s swimming ability was reduced. We found that E− adults did not have impaired locomotion, and, in fact, had elevated swimming activity in response to continued startle stimuli. These results contrast with our previous findings where fish had combined VitE and vitamin C deficiencies that caused significant myopathy in the E− adults and impaired startle responses [22]. These latter findings were expected because compound antioxidant-nutrient deficiencies frequently lead to significantly more severe pathophysiological (myopathic) consequences than do isolated deficiencies [36,37]. When E− fish were fed a VitE-deficient diet with excess vitamin C (3500 mg/kg) and soybean lecithin (which has only 20% PC), we found that the E− swam slower and with multiple taps became speedier [21]. These findings are in contrast to the present study where the fish were fed a structured lecithin (Lipoid PC 18:0/18:0), which would provide a substantially higher choline intake to the animals and may be protective of neurologic function [38]. E− fish in the present study were not vitamin C-deficient and were not motor-impaired relative to E+ fish, and their swim speeds were not different (E+ 8.4 cm/s vs E− 9.2 cm/s, p=0.28; t-test). Thus, their enhanced startle response suggests a neurological failure to habituate to the tap sound (i.e. learn to ignore a repeated, non-harmful stimulus). This failure could be due to an underlying disruption of inhibitory signaling within the brain. Specifically, estimates of γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA), a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in vertebrates [39], were half of those of E+ brains (p< 0.0001; Supplementary Table 1). However, we were unable to detect and/or confirm the identity of other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine and serotonin. Numerous neurotransmitters have been measured successfully in zebrafish [40]; thus, we plan to improve our methodologies in the future to target neurotransmitters. Whether, and to what extent, disruption of neurotransmitter signaling contributed to the learning impairments associated with VitE deficiency requires additional research.

VitE deficiency led to decreases in brain PUFAs, especially DHA (Figure 3). Ten DHA-PLs were significantly lower in E− brains (Figure 5). Such PL changes may compromise learning, as brain DHA-PL modulates membrane fluidity and function [42], which can influence neuronal signaling [43] and several DHA-PLs are biomarkers for increased dementia risk in humans [41]. Additionally, LysoPC 22:6 was decreased in E− brains (Figure 6). This lysoPL is the primary DHA transport form to the vertebrate brain [34,35], including the zebrafish brain [33].

With regard to changes in lipid composition and VitE’s role as a peroxyl radical scavenger [44], reduced lipophilic antioxidant protection from VitE and the ensuing peroxidation of brain PUFAs potentially re-directs glucose utilization by enhancing requirements for the endogenous reducing equivalents, such as NADPH, which is needed for regeneration of glutathione from GSSG by glutathione reductase [45]. This linkage is provocative because decreased brain glucose uptake is an early sign of dysfunction in AD mouse models [46]. Our findings that β-hydroxy-butyrate and ketogenic amino acids are elevated in E− brains (Figure 7) while glycolytic and citric acid cycle intermediates are decreased (Figures 7 and 8), provide additional evidence to support the notion that a shift in substrate preference takes place to counter the brain glucose depletion caused by VitE deficiency. Further, these changes in substrates used in brain energy metabolism are found in both animals and humans. Specifically, ketogenic diets provide therapeutic benefit in animal models of dementia [47]. Additionally, quantitative kinetic positron emission tomography–magnetic resonance imaging of human brain glucose and acetoacetate metabolism confirms that the brain has lower brain energy metabolism in dementias (mild cognitive impairment and AD) [48]. Thus, Croteau et al [48] conclude that during dementia, the deterioration in brain energy metabolism is specific to glucose; further their results suggest that a ketogenic intervention would increase energy availability for the brain [48]. Remarkably, we find that the E− zebrafish spontaneously potentiates the availability of brain ketones.

It is also noteworthy that we observed enhanced generation of hydroxylated n-3 and n-6 PUFAs (Figure 4) due to both elevated oxidative stress and ensuing autoxidation (e.g. F4 neuroprostanes) as well as potentially in increased activity of lipoxygenase (LOX) enzymes (e.g. 5- and 12-HETE). We did not assess gene/protein expression or enzymatic activity in the present study, therefore follow-up analyses focused on differential regulation of enzymes involved in PUFA metabolism are necessary to investigate potential effects of VitE deficiency and altered cellular antioxidant status on redox-mediated enzymatic functions. Various tocopherols and tocotrienols inhibit LOX enzyme function in vitro [49,50], VitE most strongly inhibits production of non-regiospecific, “random” hydroxylipid derivatives that originate from free radical intermediates, which may have escaped the active site of the enzyme and thus are accessible to radical scavengers [51]. This function is analogous to that of the pharmaceutical agents, ferrostatin-1 and liprostatin-1 [52], which inhibit PUFA autoxidation, rather than specifically inhibit LOX activity, and thereby rescue cells from lipid peroxidation-induced cell death. The degree to which these outcomes translate to in vivo models remains a compelling area for further research. Furthermore, while beyond the scope of the present study, investigations focused on the redox-regulation of other enzymes, such as those involved in energy metabolism (e.g. GAPDH [53,54]), also are required.

Decreases in both CDP-choline and ethanolamine in E−brains (Figure 9) suggest enhanced PC turnover and remodeling, as previously reported in VitE-deficient zebrafish embryos [24,25]. Associated decreases in choline within E− brains deserves individual attention, given the role choline has in both neurodevelopment [55] and preservation of cognitive function throughout adulthood [56]. Additionally, neuroprotective effects may be mediated through choline’s role as a methyl-donor [57]. Therefore, our findings that choline and choline-derived methyl-donor metabolites, such as betaine and SAM, are decreased in E− brains (Figure 9B) suggests disruption of methylation reactions that could subsequently affect cognition, since methyl-donor deficiency has been found to compromise learning by disturbing DNA and/or histone methylation in the brain [58].

In conclusion, inadequate brain VitE leads to increases in lipid peroxidation, as well as changes in brain lipid composition. Further, the depletion of choline and the dysregulation of PC composition suggests that methyl donor availability becomes limiting as the animal attempts to correct the loss of DHA-PC. VitE deficiency also resulted in decreases in metabolite concentrations in the glycolytic pathway, the pentose phosphate pathway and the citric acid cycle; these outcomes suggest that the energy demand to repair the damage caused by increased lipid peroxidation alters steady-state energy metabolism. Increases in β-hydroxybutyrate and ketogenic substrates further emphasize that the brain has altered energy metabolism with increased ketone availability in the E− brain. Taken together, our findings suggest that VitE plays a major role in preventing the dysregulation of brain energy metabolism by protecting lipids from increased peroxidation, and that its deficiency induces a variety of metabolic alterations that have largely been under appreciated.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Chronic vitamin E (VitE) deficiency impaired cognitive function in adult zebrafish

Deficits in VitE-deficient (E−) fish coincided with greater brain lipid peroxidation

Chronic VitE deficiency also altered the E− brain phospholipid composition

Brain choline and energy metabolism were disturbed in E− fish

The combined effects of these perturbations in E− brains likely underlie cognitive defects

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carrie Barton, Scott Leonard, and Dr. Michael Simonich for their outstanding technical assistance. NIH S10RR027878 (MGT), NIEHS P30ES000210 (RT), and Oregon State University Center for Healthy Aging Research LIFE (MM) grants supported this work.

Abbrevations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ARA

20:4 n-6, arachidonic acid

- DHA

22:6 n-3, docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

20:5 n-3, eicosapentaenoic acid

- GSH

glutathione

- LPC

22:6, lysophosphatidylcholine containing DHA

- LysoPLs

lyso-phospholipids

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PLs

phospholipids

- PUFAs

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- α-tocopherol

VitE, vitamin E

- E−

VitE− deficient or

- E+

sufficient

- Danio rerio

zebrafish

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Rest O, Berendsen AA, Haveman-Nies A, de Groot LC. Dietary patterns, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:154–168. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang YT, Chang WN, Tsai NW, Huang CC, Kung CT, Su YJ, Lin WC, Cheng BC, Su CM, Chiang YF, Lu CH. The roles of biomarkers of oxidative stress and antioxidant in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:182303. doi: 10.1155/2014/182303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green P, Glozman S, Kamensky B, Yavin E. Developmental changes in rat brain membrane lipids and fatty acids. The preferential prenatal accumulation of docosahexaenoic acid. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:960–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed TT. Lipid peroxidation and neurodegenerative disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1302–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalueff AV, Stewart AM, Gerlai R. Zebrafish as an emerging model for studying complex brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruhl T, Jonas A, Seidel NI, Prinz N, Albayram O, Bilkei-Gorzo A, von der Emde G. Oxidation and cognitive impairment in the aging zebrafish. Gerontology. 2015;62:47–57. doi: 10.1159/000433534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingold KU, Burton GW, Foster DO, Hughes L, Lindsay DA, Webb A. Biokinetics of and discrimination between dietary RRR- and SRR-alpha-tocopherols in the male rat. Lipids. 1987;22:163–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02537297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clement M, Dinh L, Bourre JM. Uptake of dietary RRR-alpha- and RRR-gamma-tocopherol by nervous tissues, liver and muscle in vitamin-E-deficient rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1256:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulatowski L, Manor D. Vitamin E trafficking in neurologic health and disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013;33:87–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behl C. Vitamin E protects neurons against oxidative cell death in vitro more effectively than 17-beta estradiol and induces the activity of the transcription factor NF-kappaB. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2000;107:393–407. doi: 10.1007/s007020070082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulatowski L, Dreussi C, Noy N, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Klein E, Manor D. Expression of the alpha-tocopherol transfer protein gene is regulated by oxidative stress and common single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:2318–2326. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copp RP, Wisniewski T, Hentati F, Larnaout A, Ben Hamida M, Kayden HJ. Localization of alpha-tocopherol transfer protein in the brains of patients with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency and other oxidative stress related neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. 1999;822:80–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokol RJ. Vitamin E and neurologic deficits. Adv Pediatr. 1990;37:119–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishida Y, Yokota T, Takahashi T, Uchihara T, Jishage K, Mizusawa H. Deletion of vitamin E enhances phenotype of Alzheimer disease model mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukui K, Nakamura K, Shirai M, Hirano A, Takatsu H, Urano S. Long-Term Vitamin E-Deficient Mice Exhibit Cognitive Dysfunction via Elevation of Brain Oxidation. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2015;61:362–368. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.61.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dysken MW, Sano M, Asthana S, Vertrees JE, Pallaki M, Llorente M, Love S, Schellenberg GD, McCarten JR, Malphurs J, Prieto S, Chen P, Loreck DJ, Trapp G, Bakshi RS, Mintzer JE, Heidebrink JL, Vidal-Cardona A, Arroyo LM, Cruz AR, Zachariah S, Kowall NW, Chopra MP, Craft S, Thielke S, Turvey CL, Woodman C, Monnell KA, Gordon K, Tomaska J, Segal Y, Peduzzi PN, Guarino PD. Effect of vitamin E and memantine on functional decline in Alzheimer disease: the TEAM-AD VA cooperative randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:33–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farina N, Llewellyn D, Isaac MG, Tabet N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD002854. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002854.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shichiri M, Yoshida Y, Ishida N, Hagihara Y, Iwahashi H, Tamai H, Niki E. alpha-Tocopherol suppresses lipid peroxidation and behavioral and cognitive impairments in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1801–1811. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukui K, Kawakami H, Honjo T, Ogasawara R, Takatsu H, Shinkai T, Koike T, Urano S. Vitamin E deficiency induces axonal degeneration in mouse hippocampal neurons. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2012;58:377–383. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.58.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller GW, Labut EM, Lebold KM, Floeter A, Tanguay RL, Traber MG. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) fed vitamin E-deficient diets produce embryos with increased morphologic abnormalities and mortality. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebold KM, Lohr CV, Barton CL, Miller GW, Labut EM, Tanguay RL, Traber MG. Chronic vitamin E deficiency promotes vitamin C deficiency in zebrafish leading to degenerative myopathy and impaired swimming behavior. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;157:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi J, Leonard SW, Kasper K, McDougall M, Stevens JF, Tanguay RL, Traber MG. Novel function of vitamin E in regulation of zebrafish (Danio rerio) brain lysophospholipids discovered using lipidomics. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1182–1190. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M058941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDougall M, Choi J, Kim HK, Bobe G, Stevens JF, Cadenas E, Tanguay R, Traber MG. Lethal dysregulation of energy metabolism during embryonic vitamin E deficiency. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;104:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDougall MQ, Choi J, Stevens JF, Truong L, Tanguay RL, Traber MG. Lipidomics and H2(18)O labeling techniques reveal increased remodeling of DHA-containing membrane phospholipids associated with abnormal locomotor responses in alpha-tocopherol deficient zebrafish (danio rerio) embryos. Redox Biol. 2016;8:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podda M, Weber C, Traber MG, Packer L. Simultaneous determination of tissue tocopherols, tocotrienols, ubiquinols, and ubiquinones. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frei B, England L, Ames BN. Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6377–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Truong L, Mandrel D, Mandrell R, Simonich M, Tanguay RL. A rapid throughput approach identifies cognitive deficits in adult zebrafish from developmental exposure to polybrominated flame retardants. Neurotoxicology. 2014;43:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knecht AL, Truong L, Simonich MT, Tanguay RL. Developmental benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) exposure impacts larval behavior and impairs adult learning in zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;59:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elie MR, Choi J, Nkrumah-Elie YM, Gonnerman GD, Stevens JF, Tanguay RL. Metabolomic analysis to define and compare the effects of PAHs and oxygenated PAHs in developing zebrafish. Environ Res. 2015;140:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burton GW, Joyce A, Ingold KU. First proof that vitamin E is major lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human blood plasma. Lancet. 1982;2:327. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in cells: oxidizability is a function of cell lipid bis-allylic hydrogen content. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4449–4453. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guemez-Gamboa A, Nguyen LN, Yang H, Zaki MS, Kara M, Ben-Omran T, Akizu N, Rosti RO, Rosti B, Scott E, Schroth J, Copeland B, Vaux KK, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Quek DQ, Wong BH, Tan BC, Wenk MR, Gunel M, Gabriel S, Chi NC, Silver DL, Gleeson JG. Inactivating mutations in MFSD2A, required for omega-3 fatty acid transport in brain, cause a lethal microcephaly syndrome. Nat Genet. 2015;47:809–813. doi: 10.1038/ng.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen LN, Ma D, Shui G, Wong P, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Zhang X, Wenk MR, Goh EL, Silver DL. Mfsd2a is a transporter for the essential omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid. Nature. 2014;509:503–506. doi: 10.1038/nature13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagarde M, Bernoud N, Brossard N, Lemaitre-Delaunay D, Thies F, Croset M, Lecerf J. Lysophosphatidylcholine as a preferred carrier form of docosahexaenoic acid to the brain. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16:201–204. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:201. discussion 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill KE, Motley AK, May JM, Burk RF. Combined selenium and vitamin C deficiency causes cell death in guinea pig skeletal muscle. Nutr Res. 2009;29:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill KE, Motley AK, Li X, May JM, Burk RF. Combined selenium and vitamin E deficiency causes fatal myopathy in guinea pigs. J Nutr. 2001;131:1798–1802. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabassum S, Haider S, Ahmad S, Madiha S, Parveen T. Chronic choline supplementation improves cognitive and motor performance via modulating oxidative and neurochemical status in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avoli M, Krnjevic K. The Long and Winding Road to Gamma-Amino-Butyric Acid as Neurotransmitter. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43:219–226. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2015.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santos-Fandila A, Vazquez E, Barranco A, Zafra-Gomez A, Navalon A, Rueda R, Ramirez M. Analysis of 17 neurotransmitters, metabolites and precursors in zebrafish through the life cycle using ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2015;1001:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mapstone M, Cheema AK, Fiandaca MS, Zhong X, Mhyre TR, MacArthur LH, Hall WJ, Fisher SG, Peterson DR, Haley JM, Nazar MD, Rich SA, Berlau DJ, Peltz CB, Tan MT, Kawas CH, Federoff HJ. Plasma phospholipids identify antecedent memory impairment in older adults. Nat Med. 2014;20:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nm.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres M, Price SL, Fiol-Deroque MA, Marcilla-Etxenike A, Ahyayauch H, Barcelo-Coblijn G, Teres S, Katsouri L, Ordinas M, Lopez DJ, Ibarguren M, Goni FM, Busquets X, Vitorica J, Sastre M, Escriba PV. Membrane lipid modifications and therapeutic effects mediated by hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid on Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838:1680–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bazan NG, Musto AE, Knott EJ. Endogenous signaling by omega-3 docosahexaenoic acid-derived mediators sustains homeostatic synaptic and circuitry integrity. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;44:216–222. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li B, Pratt DA. Methods for determining the efficacy of radical-trapping antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;82:187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maiorino M, Conrad M, Ursini F. GPx4, lipid peroxidation, and cell death: discoveries, rediscoveries, and open issues. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017 doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholson RM, Kusne Y, Nowak LA, LaFerla FM, Reiman EM, Valla J. Regional cerebral glucose uptake in the 3×TG model of Alzheimer’s disease highlights common regional vulnerability across AD mouse models. Brain Res. 2010;1347:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raefsky SM, Mattson MP. Adaptive responses of neuronal mitochondria to bioenergetic challenges: Roles in neuroplasticity and disease resistance. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;102:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Croteau E, Castellano CA, Fortier M, Bocti C, Fulop T, Paquet N, Cunnane SC. A cross-sectional comparison of brain glucose and ketone metabolism in cognitively healthy older adults, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arai H, Nagao A, Terao J, Suzuki T, Takama K. Effect of d-alpha-tocopherol analogues on lipoxygenase-dependent peroxidation of phospholipid-bile salt micelles. Lipids. 1995;30:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02538266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S, Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Jiang J, Anthonymuthu T, Mohammadyani D, Yang Q, Proneth B, Klein-Seetharaman J, Watkins S, Bahar I, Greenberger J, Mallampalli RK, Stockwell BR, Tyurina YY, Conrad M, Bayir H. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:81–90. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noguchi N, Yamashita H, Hamahara J, Nakamura A, Kuhn H, Niki E. The specificity of lipoxygenase-catalyzed lipid peroxidation and the effects of radical-scavenging antioxidants. Biol Chem. 2002;383:619–626. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zilka O, Shah R, Li B, Friedmann Angeli JP, Griesser M, Conrad M, Pratt DA. On the mechanism of cytoprotection by ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 and the role of lipid peroxidation in ferroptotic cell death. ACS Cent Sci. 2017;3:232–243. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peralta D, Bronowska AK, Morgan B, Doka E, Van Laer K, Nagy P, Grater F, Dick TP. A proton relay enhances H2O2 sensitivity of GAPDH to facilitate metabolic adaptation. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reisz JA, Wither MJ, Dzieciatkowska M, Nemkov T, Issaian A, Yoshida T, Dunham AJ, Hill RC, Hansen KC, D’Alessandro A. Oxidative modifications of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulate metabolic reprogramming of stored red blood cells. Blood. 2016;128:e32–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeisel SH. Nutrition in pregnancy: the argument for including a source of choline. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:193–199. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S36610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engelborghs S, Gilles C, Ivanoiu A, Vandewoude M. Rationale and clinical data supporting nutritional intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Clin Belg. 2014;69:17–24. doi: 10.1179/0001551213Z.0000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sable P, Kale A, Joshi A, Joshi S. Maternal micronutrient imbalance alters gene expression of BDNF, NGF, TrkB and CREB in the offspring brain at an adult age. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2014;34:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomizawa H, Matsuzawa D, Ishii D, Matsuda S, Kawai K, Mashimo Y, Sutoh C, Shimizu E. Methyl-donor deficiency in adolescence affects memory and epigenetic status in the mouse hippocampus. Genes Brain Behav. 2015;14:301–309. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.