Abstract

Objective

To determine the reproducibility of classifying uterine fibroid using the 2011 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system.

Methods

The present retrospective cohort study included patients presenting for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids at the Gynecology Fibroid Clinic at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA, between April 1, 2013 and April 1, 2014. Magnetic resonance imaging of fibroid uteri was performed and the images were independently reviewed by two academic gynecologists and two radiologists specializing in fibroid care. Fibroid classifications assigned by each physician were compared and the significance of the variations was graded by whether they would affect surgical planning.

Results

There were 42 fibroids from 23 patients; only 6 (14%) fibroids had unanimous classification agreement. The majority (36 [86%]) had at least two unique answers and 4 (10%) fibroids had four unique classifications. Staging variation was not associated with physician specialty. More than one-third of the classification discrepancies would have impacted surgical planning.

Conclusion

FIGO fibroid classification was not consistent among four fibroid specialists. The variation was clinically significant for 36% of the fibroids. Additional validation of the FIGO fibroid classification system is needed.

Keywords: Abnormal uterine bleeding, Fibroids, FIGO, Leiomyoma, Myoma, Staging

1. Introduction

Uterine fibroids are the most common reproductive tract tumor and are prevalent in up to 80% of women by the age of 50 [1]. Communicating the relationship of fibroids to the mucosal and serosal surfaces of the uterus is important for several reasons. Women with symptomatic fibroids diagnosed before completing child-bearing who elect to undergo uterine-conserving treatment are focused on the impact of treatment on fertility. These risks are impacted by the degree of fibroid extension into the myometrium. For intramural fibroids, transmural incisions carry a higher risk than removing pedunculated fibroids, and can influence whether the procedure can be completed laparoscopically or requires open surgery. Likewise, the risk of hysteroscopic myomectomy also increases when fibroids extend deeper into the myometrium. Moreover, a comparable classification system for fibroid uteri is urgently needed for research studies.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification system for abnormal uterine bleeding is intended to help both clinicians and researchers better categorize the causes of bleeding and plan treatments [2–4]. Prior to the institution of the FIGO abnormal uterine bleeding nomenclature, there was substantial misunderstanding in terminology and regional variation in nomenclature. A classification system for submucosal fibroids that reported the relationship of the fibroid to the mucosal surface of the uterus was introduced earlier than 20 years ago by Wamsteker et al. [5] and was later adopted by the European Society of Hysteroscopy. FIGO adopted and extended this classification system to all fibroids in the uterus by describing the relationship of fibroids to both the serosal and mucosal uterine surfaces [6].

The FIGO classification system [6] retains the original submucosal relationship of types 0–2, but extends staging to an additional six categories. Type 3 fibroids abut the endometrium but are completely intramural. Type 4 describes a completely intramural fibroid; types 5 and 6 are defined by the relationship to the serosal layer; type 7 describes fibroids that are pedunculated on the sub-serosal surface; and type 8 refers to fibroids found in ectopic locations such as the cervix. Additionally, FIGO staging allows a range of stages if the fibroid traverses multiple layers; for instance, a fibroid with less than half of its volume in the uterine cavity and extending to the sub-serosal layer could be labeled type 2–5.

The FIGO PALM-COEIN method is being adopted internationally. However, the limitations of real-world use of this fibroid classification system are not well described in the literature [7]. The present study was focused on the application of the FIGO anatomic uterine fibroid classification system in clinical practice.

2. Materials and methods

The present retrospective cohort study enrolled women who presented to the Gynecology Fibroid Clinic at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA, for treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids between April 1, 2013, and April 1, 2014. Participants underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for clinical care and were not enrolled in any other clinical trial. The Mayo Clinic institutional review board approved the study and patients who had authorized the use of their medical record for research were included in the study; additional informed consent was not required.

A gynecology research fellow who was not involved in staging the fibroids randomly selected one to three fibroids from each patient; they attempted to select the dominant fibroid and a second additional fibroid for women with multiple fibroids.

Static images of each fibroid were captured with sagittal, axial, and coronal orientation in the plane of their maximal diameter; fibroids were labeled, “A” representing the first fibroid, with subsequent fibroids designated “B” and “C” as applicable. These images were reviewed by radiologists (G.K.H., K.R.B.) for accuracy. Using the static images and the series/image number, the fibroids could be mapped to the original MRI examination using the QREADS online system (Mayo Clinic Ventures, Rochester, MN, USA).

The staging of each leiomyoma was determined using the FIGO anatomic sub-classification system by four independent readers; the manuscript by Munro et al. [6] and a figure demonstrating location of the fibroids were provided for the readers. The four physicians—two gynecologists (S.K.L-T. and M.R.H.) and two radiologists (G.K.H. and K.R.B.)—were experts in the evaluation and treatment of uterine fibroids; the study center averages 15–20 external referrals of women with symptomatic fibroids monthly. Both gynecologists perform myomectomies routinely, and both radiologists perform focused ultrasound ablation of fibroids.

The number of unique classifications assigned to each fibroid was recorded. By way of example, if three readers determined that a fibroid was type 5 and the fourth reader labeled it as type 6, this would be recorded as two unique answers; if all four readers recorded different fibroid types, there would be four unique answers. A sensitivity analysis was performed, excluding any discrepancies if the ranges of stages overlapped with other answers. For instance, for the sensitivity analysis, a range of type 2–5 was considered no different than a type 4 fibroid.

The significance of staging differences was then categorized based on the clinical relevance of the discrepancy. Staging differences were recorded based on whether they would have clinical implications (Yes/No classification). An example of a staging difference with clinical implications would be a fibroid staged as type 2 by one expert and as type 3 by others because a hysteroscopic myomectomy could be performed on a type-2 fibroid, but not a type-3 fibroid (Table 1). For patients who went on to choose surgical management (myomectomy or hysterectomy), attempts were made to match the description of fibroid location in the operative report to that assigned by the readers.

Table 1.

Examples of significant differences in fibroid stages and explanations for the significance assigned.

| Clinical impact | Difference in staging by independent readers | Reason for significance level |

|---|---|---|

| No clinical implications | 3 vs 5 | Minimal change in risk during myomectomy |

| 4 vs 5 | ||

| 4 vs 6 | ||

| 5 vs 6 | ||

| Clinical implications | 1 vs 2 | Could require greater hysteroscopic surgery expertise for deeper fibroids |

| 0 vs 1 | ||

| 0 vs 2 | ||

| 2 vs 3 | Stage 3 or 4 is inappropriate for hysteroscopic myomectomy | |

| 2 vs 4 | ||

| 5 vs 7 | Could require greater surgical expertise for an intramural/subserosal fibroid (stage 5 or 6) compared with a pedunculated fibroid (stage 7) | |

| 6 vs 7 |

Finally, each fibroid was measured in three perpendicular planes with QREADS and volumes were calculated using the formula for the volume of a prolate ellipsoid. The size of the fibroid was analyzed in terms of impact on the staging results using the Shapiro–Wilk test to compare the significance of two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for analyses of the number of unique stages. Fibroid size was expressed as the mean±SD. A Cohen kappa statistic was calculated for inter-reader and intra-specialty agreement. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

There were 25 patients who presented for treatment of uterine fibroids who had complete MRI examination details available from the study period. After MRI, one patient was excluded owing to having only adenomyosis, and another had a severe motion artifact that made the MRI results unreadable. Consequently, 23 women were included in the analysis; five had only one fibroid evaluated, 17 had two fibroids staged, and one patient had three fibroids included, comprising a total sample of 42 fibroids (Table 2).

Table 2.

FIGO staging of fibroids by 4 independent physicians. a

| Fibroid b | FIGO classification c | Number of unique classifications | Clinical implications | Fibroid diameter, cm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| 1A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | No | 7.6±2.2 |

| 1B | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2–5 | 3 | No | 8.5±0.5 |

| 2A | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2–5 | 2 | No | 8.9±0.6 |

| 3A | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 2 | No | 2.6±0.6 |

| 3B | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 2 | No | 3.1±0.3 |

| 4A | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | No | 6.0±0.5 |

| 4B | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | No | 4.3±0.1 |

| 4C | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | No | 3.8±0.9 |

| 5A | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 2 | No | 9.6±1.2 |

| 6A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Yes | 3.7±0.3 |

| 6B | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | No | 3.6±0.7 |

| 7A | 0 | 2–5 | 8 | 0 | 3 | Yes | 3.1±0.6 |

| 7B | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 2 | No | 4.7±0.4 |

| 8A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Yes | 2.4±0 |

| 8B | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | No | 4.1±0.4 |

| 9A | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | Yes | 7.5±0.8 |

| 9B | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | No | 1.8±0.1 |

| 10A | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 2 | Yes | 12.5±1.5 |

| 10B | 2–5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Yes | 3.3±0.3 |

| 11A | 3 | 3–5 | 4–5 | 4 | 4 | No | 8.3±1.1 |

| 11B | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | Yes | 3.2±0.7 |

| 12A | 4 | 3–6 | 4 | 2 | 3 | Yes | 4.1±0.4 |

| 13A | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | No | 4.2±0.2 |

| 13B | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | No | 1.9±0.2 |

| 14A | 4 | 3–5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | No | 5.1±0.1 |

| 15A | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | No | 7.6±0.4 |

| 15B | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | No | 4.7±0.6 |

| 16A | 5 | 6 | 6 | 3–5 | 3 | No | 12.4±1.6 |

| 17A | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | No | 5.7±0.5 |

| 17B | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3–5 | 3 | Yes | 5.5±0.4 |

| 18A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | No | 2.6±0.1 |

| 18B | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | Yes | 3.0±0.2 |

| 19A | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 2 | Yes | 4.2±0.8 |

| 19B | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 3 | Yes | |

| 20A | 3 | 3–5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | No | 10.4±1.2 |

| 20B | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | No | 3.3±0.2 |

| 21A | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3–5 | 3 | No | 14.1±2.8 |

| 21B | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4–5 | 4 | No | 7.9±0.8 |

| 22A | 4 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | No | 9.3±0.8 |

| 22B | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2–4 | 4 | Yes | 4.1±0 |

| 23A | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4–5 | 4 | No | 12.8±1.0 |

| 23B | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | No | 4.4±0.1 |

Values are given as number or mean±SD.

Where multiple fibroids were included from a single patient, the different fibroids were label A, B, and C (where applicable).

Letters A–D represent each of the four physicians classifying fibroids.

Of the 42 fibroids, only 6 (14%) had a single FIGO classification assigned by all four readers; two of these were type 7, three were type 4, and one was type 2. There were 20 fibroids (48%) that had 2 unique classifications assigned, 12 (29%) had 3 classifications, and 4 fibroids (10%) had different types assigned by each of the four physicians assessing them. Agreement between the two radiologists (22 [52%]) occurred slightly more frequently than among the gynecologists (19 [45%]). The intra-specialty kappa was 0.42 for the radiologists and 0.35 for the gynecologists; indicating moderate and fair agreement, respectively.

Of the 42 fibroids, 36% (15) had staging discrepancies that could impact surgical management and 64% (27) had fibroid-staging discrepancies that were determined as not having clinical implications. Examples of staging discordance that would affect surgical management are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Figure 3 illustrates an example of discordant staging that would likely not change the clinical management of the larger fibroid despite this fibroid having four unique classifications; the management of the smaller fibroid would be slightly affected.

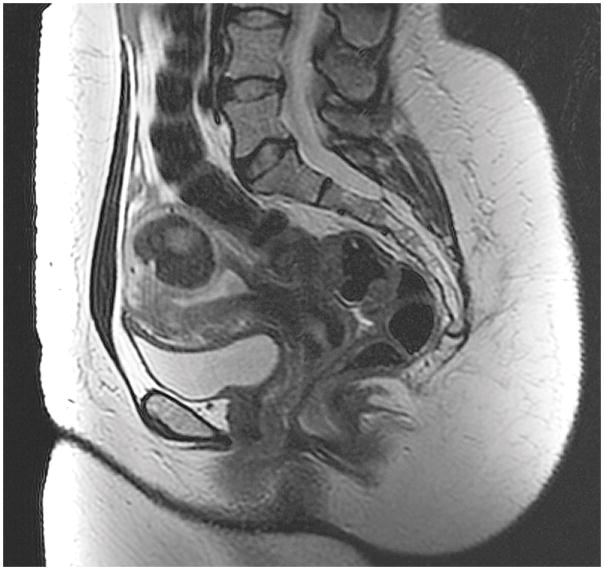

Figure 1.

In fibroid 12A, a typical T2 dark fibroid arising from the posterior uterine wall extends into the uterine cavity inferiorly, distorting the serosa. Fibroid 12A was classified as type 2, type 4, and type 3–6.

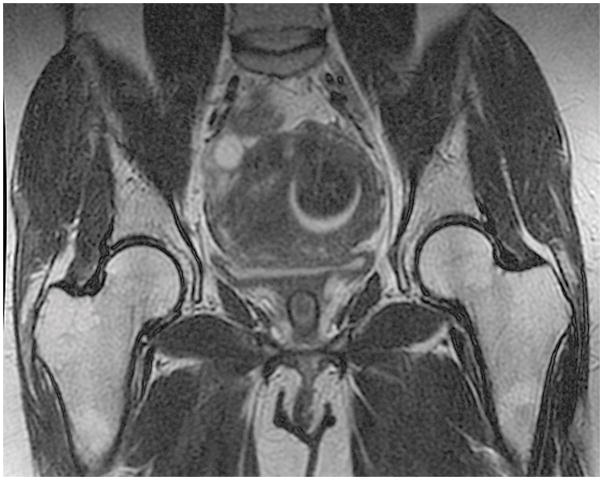

Figure 2.

In fibroid 6A, a fibroid arising from the posterior wall impacts the uterine cavity. It is almost exactly 50% intramural from a sagittal view (A). It appears to be <50% intramural using a coronal view (B). With an axial view, it appears to be >50% intramural (C).

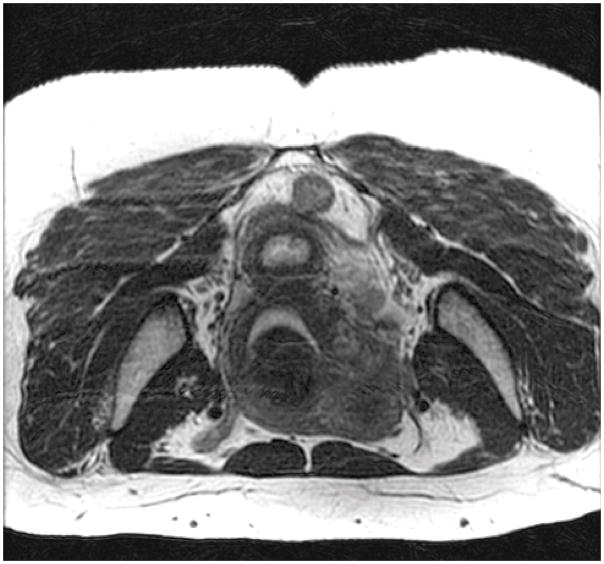

Figure 3.

Fibroid 11A is the larger fibroid arising from the posterior uterine wall compressing the uterine cavity and extending to the serosa; it was classified as type 3, type 4, type 3–5, and type 4–5. 11B is the smaller T2 dark subserosal fibroid with possible extension into the myometrium; it was classified as type 6 and type 7.

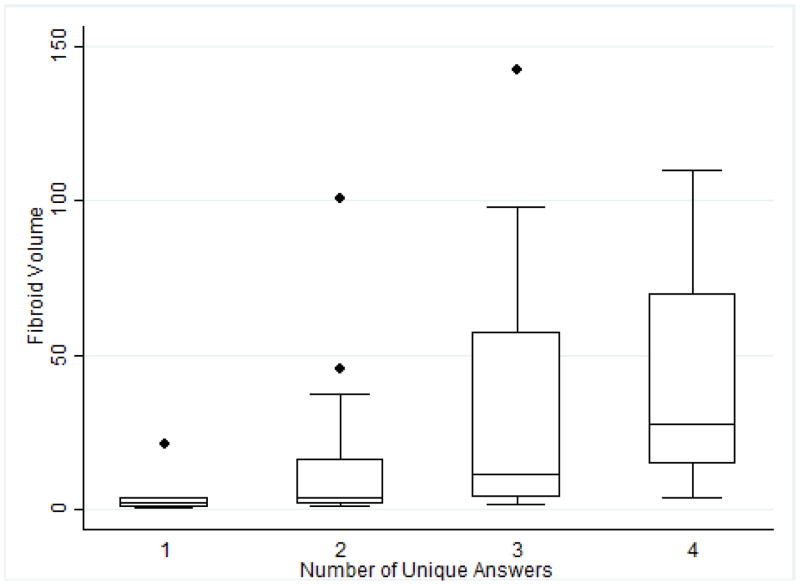

The fibroid volume affected the classification of fibroids (Figure 4). Fibroids with a higher number of unique stages had larger volumes (P=0.029); the median volume for fibroids with one unique staging was 2.2 cm3 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.33–8.03) compared with 27.8 cm3 (IQR 9.18–89.89) for fibroids with four unique classifications. Fibroid volume also had an effect on the significance of classification discrepancies; fibroids where the management would be impacted by staging discrepancies had a smaller median volume (2.25 cm3, IQR 1.5–4.9) compared with those without discrepancies affecting clinical management (9.8 cm3, IQR 3.5–37.2; P=0.001).

Figure 4.

Box plot of fibroid volume stratified by the number of unique FIGO fibroid classifications recorded by the four readers. Abbreviation: FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

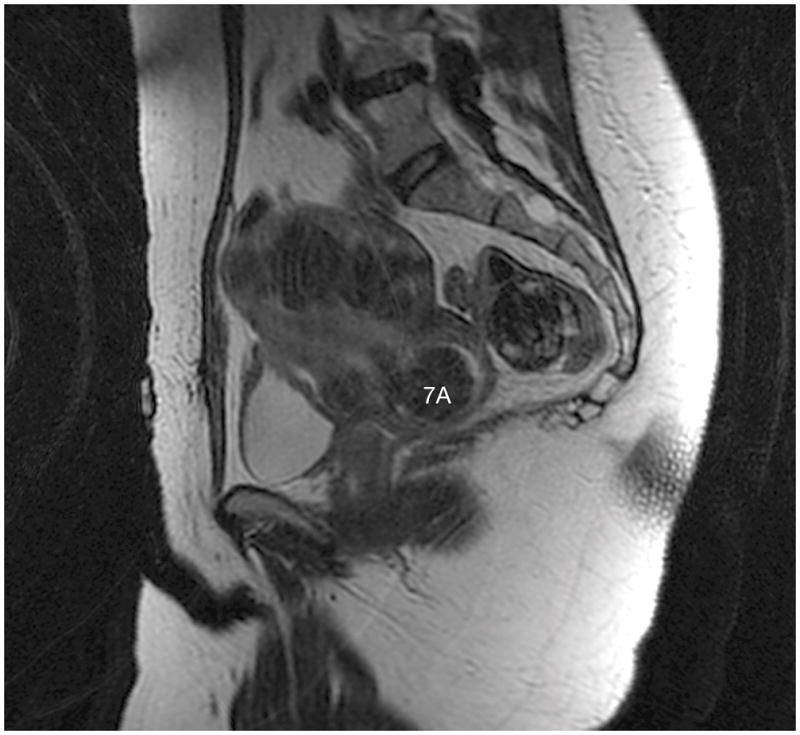

The highest staging discrepancy occurred for fibroid 7A; two physicians labeled it as type 0, one classified it as type 8, and one classified it as type 2–5 (Figure 5). Following staging, the experts concluded after discussion that both type 0 and type 8 were correct because it was a pedunculated fibroid in the cervix. Both pieces of information were important for the management of this tumor; this consisted of hysteroscopic and manual resection of a prolapsing fibroid.

Figure 5.

Fibroid 7A shows a typical T2 dark fibroid arising in the cervix that was classified as type 0, type 2–5, and type 8.

In the sensitivity analysis that accounted for the range of stages, 6 (14%) had a single stage, 28 (67%) had two unique stages, 6 (14%) had three unique stages, and 2 (5%) had four unique stages. The significance of the discrepancies was not impacted by this broader comparison.

For the 15 patients who underwent surgery, it was not possible to match the surgical descriptions of the individual fibroids selected for the study with MRI staging. The descriptions of hysteroscopically resected fibroids from the operative notes were not completely consistent with the MRI FIGO staging. For fibroids resected by laparoscopic or abdominal myomectomy, the operative report of those described as “not entering the uterine cavity” were compared with the FIGO staging in the study; none of these were labeled as a 0, 1, or 2 as expected, but one was labeled as 2–5.

4. Discussion

The FIGO system has advanced the level of standardization in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding. However, based on the present study, additional validation of the FIGO fibroid classification system appears to be indicated for both clinical and research use. The application of FIGO staging was not consistent across physicians in the present study and this was not related to physician specialty. A larger fibroid volume was also associated with more classification discrepancies; larger fibroids could have distorted uterine landmarks, making it difficult to determine the extent of myometrial invasion.

Of the fibroids staged, 36% had staging differences that would have had a substantial impact on surgical planning. These tumors were significantly smaller; smaller tumors could be more difficult to stage accurately, and the significance of a small fibroid-classification discrepancy could be less important when there are multiple fibroids in the uterus. The other fibroids could already increase surgical risks or could change surgical planning. Of the surgical outcome data available, MRI was helpful in surgical planning but MRI was imprecise in staging.

It could be argued that, despite previous classification by a radiologist, a surgeon would review the images and the discrepancy (as shown in Figure 1) would not impact surgical management as a result. However, this type of classification discrepancy is important for research studies where classification could be an independent variable for the comparison of outcomes. Therefore, a type-2 label for a fibroid could be insufficient in explaining the outcome of an abdominal myomectomy rather than a hysteroscopic myomectomy compared with other hysteroscopically resected type-2 fibroids. Limitations to the FIGO classification system should be described and researchers should consider combining categories for studying outcomes. Also, the addition of a fibroid location outside the uterine body, such as a cervical fibroid (type 8), is an important factor in planning; ectopic location could have more value as an additional descriptor rather than a separate category.

In the present study, MRI was chosen for clinical evaluation because most of the patients had multiple or large fibroids. MRI is considered better able to distinguish fibroids than ultrasonography if there are more than four fibroids or if the uterus is larger than 375 cm [8]. MRI is the modality selected for fibroid mapping in the study clinic prior to focused ultrasound ablation or myomectomy. However, similar validation using ultrasonography is also indicated given its widespread use worldwide for fibroid diagnosis and management.

Physicians with lengthy fibroid-treatment experience performed the staging in the present study; all physicians were part of the Fibroid Clinic, a referral center at a large academic medical center. Each physician reviewed the FIGO sub-classification system and used the fibroid map to define classifications [6]. The four physicians perform uterine-conserving procedures for women of reproductive age and are aware of the risks of misdiagnosing fibroid stage. The risks of misclassifying fibroids for focused ultrasound ablation surgery include incidentally ablating a stage 0 or 1 fibroid that would subsequently pass through the cervix, causing pain or infection. Similarly, performing a laparoscopic myomectomy on a fibroid that extended further into the myometrium than expected would increase the risk of adhesions or subsequent uterine rupture from transmural incisions [9, 10]. The staging for the present study was performed in the same way it would be for clinical care and the study center.

The present study was not without limitations. All women included in the study were seeking treatment owing to significant fibroid symptoms and underwent MRI for uterine-conserving treatment options. These recruitment restrictions likely limit the generalizability of the present study I the staging of women with fewer and/or smaller fibroids, or women seeking hysterectomy who do not require MRI.

Although staging fibroids is an ideal goal, the number of different stages and ranges offered by the FIGO classification indicates a level of accuracy above what MRI and clinical physicians can offer. Even when the physicians staging fibroids were restricted to specialists and researchers, as these sub-classifications of the FIGO staging were intended, consensus was difficult. Attempting a strict classification could misguide surgical procedures and make comparative research inaccurate. Further studies would benefit from reviewing the outcomes of surgery by classification or confirmation of staging by second modalities.

Synopsis.

FIGO classification of fibroids was not consistent across physicians. Variations in staging would impact the surgical management of 36% of fibroids.

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD060503).

Footnotes

Author contributions

SKL-T conducted the MRI reviews, performed the data analyses, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. GKH, MRH, and KRB conducted the MRI reviews, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. YZ measured the fibroid volumes, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. EAS designed the study and the analyses, and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

SKL-T has received research funding, paid to the Mayo Clinic, from Truven Health Analytics Inc, and InSightec Ltd (Israel). She is on the data safety monitoring board for the Uterine Leiomyoma (fibroid) Treatment with Radiofrequency Ablation trial (ULTRA trial; Halt Medical, Inc) and has received royalties for UpToDate. GKH has received research funding from InSightec Ltd (Israel). EAS is a consultant for AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas Pharma, Bayer Health Care, Gynesonics, and Viteava, and has received royalties from UpToDate and the Massachusetts Medical Society. The authors have no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100–107. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS. The flexible FIGO classification concept for underlying causes of abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(5):391–399. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;95(7):2204–2208. 2208 e2201–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Critchley HO, Munro MG, Broder M, Fraser IS. A five-year international review process concerning terminologies, definitions, and related issues around abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(5):377–382. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wamsteker K, Emanuel MH, de Kruif JH. Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for abnormal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(5):736–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;113:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS. Outcomes from leiomyoma therapies: comparison with normal controls. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;117(4):987. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182114e36. author reply 987–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis, mapping, and measurement of uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):409–415. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi H, Kinoshita K. Evaluation of adhesion formation after laparoscopic myomectomy by systematic second-look microlaparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(4):442–446. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seracchioli R, Colombo FM, Bagnoli A, Govoni F, Missiroli S, Venturoli S. Laparoscopic myomectomy for fibroids penetrating the uterine cavity: is it a safe procedure? BJOG. 2003;110(3):236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]