Abstract

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are emerging worldwide, limiting therapeutic options. Mutational and plasmid-mediated mechanisms of colistin resistance have both been reported. The emergence and clonal spread of colistin resistance was analysed in 40 epidemiologically-related NDM-1 carbapenemase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates identified during an outbreak in a group of London hospitals. Isolates from July 2014 to October 2015 were tested for colistin susceptibility using agar dilution, and characterised by whole genome sequencing (WGS). Colistin resistance was detected in 25/38 (65.8%) cases for which colistin susceptibility was tested. WGS found that three potential mechanisms of colistin resistance had emerged separately, two due to different mutations in mgrB, and one due to a mutation in phoQ, with onward transmission of two distinct colistin-resistant variants, resulting in two sub-clones associated with transmission at separate hospitals. A high rate of colistin resistance (66%) emerged over a 10 month period. WGS demonstrated that mutational colistin resistance emerged three times during the outbreak, with transmission of two colistin-resistant variants.

Introduction

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) have emerged globally over the last decade1,2. CPE present a ‘triple threat’ of high levels of antibiotic resistance, the ability to cause invasive infections, and spread rapidly1–3. A number of centres have reported serious clinical and financial consequences related to the emergence of CPE, including high mortality rates in some reports3–5. Rates of CPE are high in some parts of the world (notably parts of Southern Europe, Israel and increasingly parts of the USA)1,5,6.

Resistance to carbapenems limits therapeutic options3,7. Colistin and other polymyxins have been used for the treatment of CPE7,8, but mutational and plasmid-mediated colistin resistance have been reported7,9–18. Evidence of horizontal transmission of mobile colistin resistance genes has recently been reported15,16,18–22, but few reports have evaluated mutational resistance in a clinical setting coupled with clonal spread9–11,20,23.

An outbreak of NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae occurred across a multicentre London group of hospitals in 2015, involving patients attending interlinking networks of clinical specialities. We investigated the isolates involved in the outbreak to identify and track the emergence of colistin-resistant CPE using whole genome sequencing.

Results

Description of the outbreak

A total of 40 patients were identified with the ‘outbreak strains’ between July 2014 and October 2015 (Fig. 1). Twenty-one cases were first identified at Hospital A, mainly from renal inpatient wards, and 19 cases at Hospital B, mainly from vascular inpatient wards. There was frequent contact between the hospitals (Fig. 2).

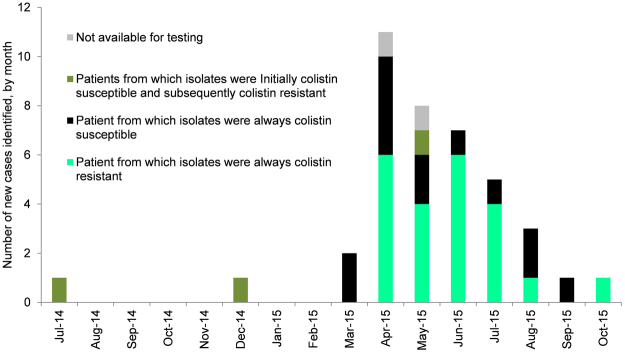

Figure 1.

Epidemic curve of the outbreak – incident cases shown. Isolates from three cases were initially colistin susceptible and subsequent isolates from the same cases were colistin resistant.

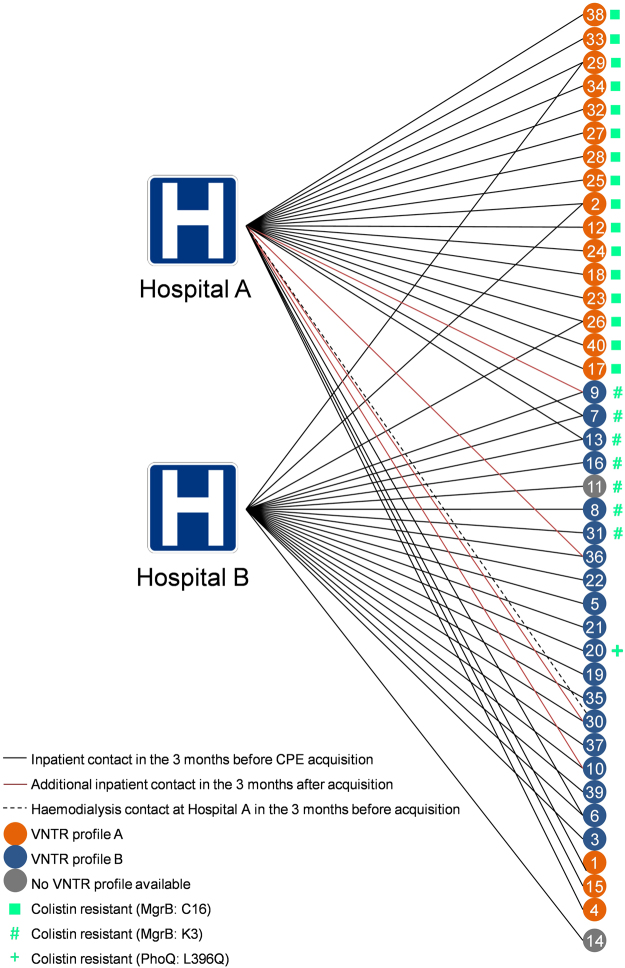

Figure 2.

Map of contact of patients with two hospitals in the group. Despite frequent inter-hospital contact, the two VNTR sub-clones remained closely associated with different hospital sites.

The clinical characteristics of the patients involved in the outbreak are listed in Table 1. Thirty patients (75%) had antibiotic exposure in the 12 months prior to the initial detection of the outbreak strain (Table 1). No patients had an identified travel history or exposure to healthcare abroad within the preceding 12 months. Twenty-two (55%) patients had a positive clinical specimen at some point during the outbreak period, and 18 (45%) were treated using either colistin or tigecycline. Outcomes were evaluated one year after the outbreak was first identified: of the 40 patients involved in the outbreak, 16 (40%) died and five were discharged with palliative/end of life care plans with no plans for readmission, giving a crude mortality rate of 52%. However, no antibiotic treatment failure-related mortality was identified following detailed clinical review of each of these cases. This may be explained in part by the relatively small number of clinical infections detected during the outbreak (urine 11, skin and soft tissue infection 9, abdominal 4, bloodstream infection 0), and the prompt initiation of combination antimicrobial therapy with colistin and tigecycline in known colonised patients who developed signs and symptoms of an infection, in accordance with local susceptibility patterns. Meropenem was not used as all isolates had an MIC > 32 mg/l. Of the patients surviving the immediate outbreak period, only three were completely discharged from the hospital system. The remainder continue to attend hospital services, including four for regular haemodialysis, and 12 with a variety of inpatient, day case and outpatient attendances.

Table 1.

Description of the patients involved in the outbreak.

| Case number | Age bracket | Speciality at admission | Specimen of first isolate | Subsequent clinical isolate (n days between screen and clinical isolate)a | Any antibiotic therapy prior to identification of NDM infectionb | CPE antibiotic therapy used post NDM identification | Initial colistin MIC (mg/L)c | Highest colistin MIC (mg/L)d | Colistin resistant at any stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KP_NDM1 | 81–90 | Renal | Urine | — | Amikacin | No antibiotics | <0.05 | 8 | Yes |

| KP_NDM2 | 51–60 | Vascular | Screening | Liver abscess (5) | Amikacin Metronidazole Piperacillin/Tazobactam Vancomycin | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | <0.05 | 16 | Yes |

| KP_NDM3 | 81–90 | Orthopaedic | Urine | — | None identified | No antibiotics | <0.05 | ||

| KP_NDM4 | 61–70 | Renal | Abdominal fluid | — | Ciprofloxacin Meropenem Metronidazole Piperacillin/Tazobactam Vancomycin | No antibiotics | <0.05 | 1 | |

| KP_NDM5 | 51–60 | Vascular | Urine | — | None identified | No antibiotics | <0.05 | ||

| KP_NDM6 | 61–70 | Cardiac | Wound (Leg) | — | Meropenem | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | Not done | <0.05 | |

| KP_NDM7 | 71–80 | Renal | Screening | Leg swab and tissue, urine (22) | None identified | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | 4 | 8 | Yes |

| KP_NDM8 | 71–80 | Vascular | Screening | None | None identified | No antibiotics | 32 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM9 | 71–80 | Renal | Screening | Urine, central veneous catheter tip (4) | Meropenem | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline, | 8 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM10 | 71–80 | Renal | Screening | None | Nystatina | No antibiotics | <0.05 | ||

| KP_NDM11 | 81–90 | Cardiac | Screening | None | None identified | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | 32 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM12 | 61–70 | Renal | Screening and urine | — | Cotrimoxazoled | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | 8 | 8 | Yes |

| KP_NDM13 | 61–70 | Cardiac | Screening | None | None identified | No antibiotics | 8 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM14 | 81–90 | Cardiac | Screening | None | Cefalexin | No antibiotics | Not available | ||

| KP_NDM15 | 61–70 | Cardiac | Screening | None | Amikacin Clarithromycin Co–amoxiclav Piperacillin/Tazobactam Vancomycin | No antibiotics | <0.05 | ||

| KP_NDM16 | 81–90 | Renal | Screening | Groin wound swab (16) | Meropenem | Tigecycline | 8 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM17 | 71–80 | Renal | Screening | Urine and mouth ulcers (235) | Co–amoxiclav Piperacillin/Tazobactam Vancomycin | Tigecycline | 16 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM18 | 51–60 | Renal | Screening | None | Ciprofloxacin Cotrimoxazoled Metronidazole Piperacillin/Tazobactam, Vancomycin, | No antibiotics | 32 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM19 | 81–90 | Renal | Screening | Urine (6) | Meropenem | Tigecycline | <0.5 | ||

| KP_NDM20 | 71–80 | Renal | Screening | Wound swab (11) | None identified | No antibiotics | <0.5 | >32 | Yes |

| KP_NDM21 | 51–60 | Renal | Screening | Urine (15) | None identified | No antibiotics | 1 | ||

| KP_NDM22 | 61–70 | Renal | Screening | Urine (254) | None identified | No antibiotics | Not done | ||

| KP_NDM23 | 61–70 | Vascular | Wound (surgical) | — | Ciprofloxacin, Vancomycin | No antibiotics | 32 | 16 | Yes |

| KP_NDM24 | 61–70 | Cardiac | Screening | None | Co-amoxiclav Ciprofloxacin Vancomycin | No antibiotics | 4 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM25 | 71–80 | Intensive Care | Screening | Wound swabs (groin and thigh) (28) | Metronidazole Piperacillin/Tazobactam Vancomycin | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | 4 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM26 | 61–70 | Renal | Screening | None | Piperacillin/Tazobactam, Vancomycin | No antibiotics | 16 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM27 | 21–30 | Intensive Care | Screening | None | Co-trimoxazoled Valganciclovird | No antibiotics | 16 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM28 | 31–40 | Intensive Care | Screening | None | Amikacin Linezolid Liposomal amphotericin, | No antibiotics | 4 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM29 | 71–80 | Vascular | Soft tissue and bone (foot) | — | Amikacin Piperacillin/ Tazobactam, Vancomycin, | No antibiotics | 8 | 2 | Yes |

| KP_NDM30 | 61–70 | Cardiac | Screening | None | Ceftriaxone | Colistimethate sodium Tigecycline | 1 | ||

| KP_NDM31 | 81–90 | Emergency Medicine | Screening | Urine (3) | Ceftriaxone Flucloxacillin Gentamycin, Metronidazole Rifampicin | No antibiotics | 8 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM32 | 51–60 | Maternity | Screening | Urine (18) | Amikacin, Caspofungin Co-trimoxazoledd Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole, Vancomycin | No antibiotics | 8 | 8 | Yes |

| KP_NDM33 | 51–60 | Intensive Care | Screening | Central veneous catheter tip, abdominal wound (5) | Co-trimoxazoled Meropenem, Nystatind | No antibiotics | 8 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM34 | 21–30 | Renal | Screening | None | Piperacillin/Tazobactam | No antibiotics | 16 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM35 | 51–60 | Renal | Soft tissue and bone (foot) | — | Ciprofloxacin, Clindamycin Vancomycin, | Colistimethate sodium, Tigecycline | <0.5 | ||

| KP_NDM36 | 61–70 | Vascular | Screening | None | Anidulanfungin Meropene Rifaximin Vancomycin | No antibiotics | <0.5 | ||

| KP_NDM37 | 91–100 | Vascular | Screening | None | Ceftriaxone | No antibiotics | <0.5 | ||

| KP_NDM38 | 0–10 | Vascular | Screening | None | Benzylpenicillin Colistimethate sodium, Gentamicin | No antibiotics | 8 | Yes | |

| KP_NDM39 | 51–60 | Vascular | Screening | None | None identified | Colistimethate sodium, Tigecycline | <0.5 | ||

| KP_NDM40 | 61–70 | Vascular | Screening | None | Isoniazidd | No antibiotics | 8 | Yes |

aColumn denotes patients who were initially identified by screening, but had a subsequent clinical isolate, the site of the first clinical isolate, and the time between the screen and the first clinical isolate.

bIdentified through case note review/electronic pharmacy records for period 2014/15.

cBold font denotes colistin resistance (>2 mg/L).

dProphylaxis post-transplant as part of approved protocols.

Colistin resistance

Colistin resistance was detected in isolates from 25/38 (65.8%) patients for which colistin susceptibility was determined; the median colistin MIC was 8 mg/L. Initial isolates from three patients (KP_NDM_1, 2 and 20) were colistin susceptible with a subsequent colistin resistant isolate (Fig. 1). Only 9/25 (36.0%) isolates identified as colistin resistant in the reference laboratory were reported as colistin resistant by the hospital clinical laboratory by disc testing, meaning that colistin resistance was not detected until late in the outbreak in July 2015. Colistin exposure in patients was not significantly associated with having a colistin resistant isolate (10/14 colistin exposed vs. 15/24 not colistin exposed, p = 0.7281). No patients were treated with colistin monotherapy.

Variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis of K. pneumoniae isolates identified two sub-clones, A and B, (Fig. 2); both profiles were indicative of multilocus sequence type ST14. There were two clusters of colistin resistant isolates, one within VNTR sub-clone A on the renal wards in Hospital A, and one within VNTR sub-clone B on the vascular wards at Hospital B (Fig. 2). VNTR sub-clone A was associated with transmission at Hospital A, and sub-clone B with transmission at Hospital B (Fig. 2). All of the 19 patients acquiring VNTR sub-clone A had inpatient contact with Hospital A in the three months prior to acquisition, compared with 4/20 patients who acquired VNTR sub-clone B (p < 0.001), whereas 19/20 patients acquiring sub-clone B had inpatient contact with Hospital B in the three months prior to acquisition, compared with 3/19 patients who acquired sub-clone A (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

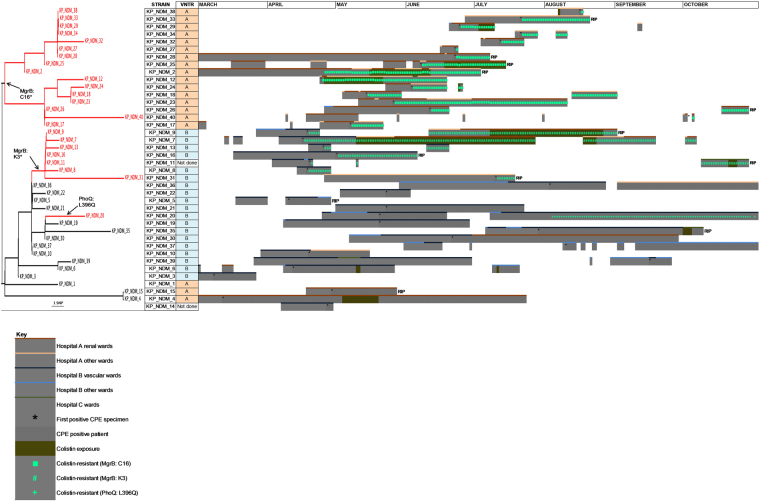

WGS showed that the two clusters of colistin resistant isolates were linked with two separate mechanisms of mutational colistin resistance: both due to different mutations each causing an early stop codon in the mgrB gene (MgrB: C16 and MgrB: K3) (Fig. 3). A third potential mechanism of mutational colistin resistance, due to a L/Q substitution at amino acid position 396 in phoQ, was identified from a single patient (KP_NDM_20), but did not spread clonally (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Patient pathways (for 40 patients between March – October 2015) and whole genome sequence Maximum Likelihood tree. The WGS tree supports the emergence and clonal spread of colistin resistance caused by two different mechanisms (MgrB: C16 and MgrB:K3), and also the emergence of a third type of colistin resistance (PhoQ:L396Q) that did not spread clonally. Red colour in tree = colistin resistant isolates; Black colour in tree = colistin susceptible isolates. Isolates KP_NDM_1 and KP_NDM_2 were first identified in July and December 2014, respectively.

The two branches of the dendrogram among the colistin resistant isolates in sub-clone A are consistent with two separate transmission events from the same patient (KP_NDM_2) (Fig. 3). Most of the isolates in the VNTR sub-clone B colistin resistant cluster appeared to have been transmitted on one vascular ward over a short period of time (Fig. 3). A transmission event to a further ward, the ICU, was suggested by the final isolate in this cluster (KP_NDM_31), which occurred on the ICU at Hospital A without obvious epidemiological contact with the vascular wards. The transmission event explaining the identification of this colistin resistant isolate on the ICU most likely occurred around a month earlier during time spent on the same non-renal inpatient ward at Hospital A with patient KP_NDM_7. Interestingly, WGS separated VNTR sub-clone A and B in different phylogenetic branches but with only a few SNPs to distinguish between them, suggesting that they were closely related and may have evolved from a common ancestral strain (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The therapeutic challenges presented by CPE are exacerbated by the emergence of colistin resistance7,9–15,17,24,25. We report a high rate of colistin resistance (66%) caused by three different mechanisms with clonal spread of colistin resistant isolates in two sub-clones circulating in different hospitals during an outbreak of CPE among a network of patients across two hospital sites linked through inpatient stays and dialysis dependence. Colistin resistance was detected late in the outbreak, and highlights the challenges of laboratory detection and therefore the risk for under-ascertainment of colistin resistance17,20. Although we did not identify any treatment failure-related mortality, this is in contrast to other studies, and is likely due to the fact that few invasive infections occurred3,17,26.

Some Gram-negative bacteria including Serratia, Brucella and Burkholderia species are inherently resistant to colistin7. Acquired colistin resistance can occur through a number of mechanisms: mutational changes in many endogenous genes involved in lipopolysaccharide synthesis, prominently including the mgrB gene and upregulation of PhoP/PhoQ, an important two-component sensor-regulator system which impacts lipopolysaccharides10–14,24,27,28, and horizontal acquisition of genes as shown by the recent discovery of plasmid-encoding mcr genes15,18–22. Much attention has focussed recently on plasmid-mediated colistin resistance15,18–22. However, our findings suggest that the clonal spread of K. pneumoniae with mutational colistin resistance may be a more important clinical threat9–11,17,20,23,29. For example, Giani et al. report a large hospital outbreak of 93 bloodstream infections caused by KPC-producing K. pneumoniae that was mostly explained by clonal expansion of a single mgrB deletion mutant9. In contrast, in our study, we identified three different mechanisms associated with colistin resistant isolates over the course of a few months. Our findings show that two different types of mutational colistin resistance (both affecting mgrB) spread clonally over a short period of time, suggesting that they do not impose a major fitness burden. This underlines the need for robust infection control interventions to prevent the clonal spread of resistance determinants. A mutational change in PhoQ was observed in a single isolate during our outbreak strain, but this variant did not spread to further patients. We were not able to detect the mobile colistin resistance genes mcr-1, -2 or -3 in any of the study isolates. Understanding of the clinical and epidemiological implications of the various types of colistin resistance is limited, with very little data on the frequency of emergence, fitness impact, and strain variation7,20,30. Furthermore, strategies to limit the emergence of colistin resistance (for example optimal colistin dosing and choosing agents that suppress colistin resistance) are in their infancy7,20,25,31,32.

The 40 patients involved in the outbreak had complex, extended or repeated, and overlapping inpatient stays and outpatient contact with our hospitals. This made understanding the origin of colistin resistant isolates challenging. Re-ordering epidemiological and patient pathway information based on WGS data provided a useful way to track the emergence and spread of colistin resistance5,33. There appeared to be an early division of the outbreak strain into two sub-clones, which circulated concurrently but separately in the renal wards and vascular wards at two hospital sites – and colistin resistance appeared to emerge independently in both sub-clones. Colistin exposure in patients was not associated with colistin-resistant isolates, probably due to the clonal spread of colistin resistant isolates.

Strengths of the study include the combination of epidemiological data and WGS analysis to highlight the emergence and spread of colistin resistant isolates. WGS also facilitated the detection of multiple types of colistin resistance. Although there is an increasing body of evidence linking the mutations identified with colistin resistance13,14,24,27,28, limitations of this study include the lack of detailed laboratory and molecular investigations to confirm that the mutations detected are responsible for colistin resistance in these particular isolates, which should be the subject of future studies. The laboratory testing of colistin susceptibility performed locally was not performed using methods recommended by EUCAST or CLSI, which were not available at the time of the outbreak, illustrating the need for timely updates of microbiological testing guidelines. We made inferences about transmission based on WGS phylogeny. This approach is commonly applied in healthcare epidemiology, but the most appropriate sampling strategy(s) and number of SNPs that define a transmission event are not yet clear5,33.

Widespread colistin resistance would likely result in increased morbidity, mortality, and direct and indirect costs associated with CPE3,4,17,26. Whilst attention has focussed on the plasmid mediated mcr genes, the emergence and clonal spread of mutational colistin resistance mediated by three distinct mechanisms over the course of two months during a single outbreak is concerning, and further limits therapeutic options for CPE.

Methods

Setting and infection control interventions

The healthcare group comprises five hospitals in London with approximately 1,500 inpatient beds and 190,000 admissions each year. The renal service was located at Hospital A and the vascular service located at Hospital B, with frequent transfer of patients between the two specialties. These hospitals experienced an outbreak of NDM-producing K. pneumoniae affecting 40 patients between July 2014 and October 20154. Additional infection control measures launched in April 2015 included enhanced screening (including renal outpatients), contact precautions for known CPE carriers, enhanced chlorine disinfection of the environment, labelling of electronic case notes for identification of readmission, regular teleconference calls internally and with PHE, and enhanced antibiotic stewardship. In response to evidence of ongoing transmission, hydrogen peroxide vapour (HPV) of patient rooms on discharge and ward-based monitors of hand and environmental hygiene were implemented in August 2015.

Microbiological and molecular investigations

Rectal or faecal screening isolates were plated onto Colorex Supercarba screening agar, and clinical isolates were processed according to local standard operating procedures. Positive colonies were identified by MALDI-TOF and disc susceptibility testing performed according to EUCAST guidelines. Initial colistin susceptibility was recorded as zone present or absent, due to lack of EUCAST interpretative guidelines at the time of the outbreak. Isolates identified as Klebsiella pneumoniae that were resistant to ertapenem or meropenem on disc testing had Etest MIC evaluation and PCR performed to screen for carbapenemase genes (Cepheid Xpert® Carba-R).

Isolates confirmed locally as NDM-producing K. pneumoniae were referred to Public Health England’s (PHE) Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) Reference Unit for characterisation. PHE performed whole genome sequencing (WGS) (HiSeq, Illumina, by PHE’s Genomic Services and Development Unit), variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis34, and (for 38/40 isolates) MIC determination using an extended panel of antimicrobials (including colistin) by agar dilution. ‘Outbreak strain’ cases were defined as those isolates that were VNTR profile A (6,3,4,0,1,1,1,3,1,1) or B (6,3,4,0,1,1,1,2,1,1); cases were still included if results at some loci were unavailable, provided the other loci matched one of these profiles. Colistin susceptibility was interpreted against EUCAST criteria (R > 2 mg/L).

For WGS analysis, reads from each genome were mapped onto the reference genome (K. pneumoniae MGH 78578) using BWA (version 0.7.9a).The SAM file generated thereby was converted to BAM with Samtools (version 1.1). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were called using the Genome Analysis Toolkit 2 (GATK2) and then filtered based on the depth of coverage (DP ≥ 5), ratio of unfiltered reads that support the reported allele compared to the reference (AD ≥ 0.8) and mapping quality (MQ ≥ 30). SNPs filtered out using these metrics, including heterozygotes were designated by ‘N’. SNPs from each genome were thereafter combined to generate a single multiple alignment file with the maximum proportion of Ns accepted at any position of the alignment set to less than 20%. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed using RAxML. BLAST was used to search for the mobile colistin resistance genes, mcr-1, -2 and -3, sequence (using 80% identity) in VelvetOptimiser de novo sequence assemblies.

Clinical epidemiology

Patients were identified from clinical isolates or screening cultures in accordance with UK national guidelines35,36. Patient details were collected prospectively using a data collection form, including patient demographics, diagnosis and comorbidities (ICD10 codes), antimicrobial treatments, and medical interventions. In order to track the emergence and spread of colistin resistant isolates, inpatient pathways of the patients involved in the outbreak were mapped to highlight overlapping inpatient stays and review possible transmission routes. The topology of the ML phylogenetic tree (reconstructed from the WGS data) was used to re-order and plot the patient pathways in order to understand likely transmission routes. Categorical variables were analysed by Fisher’s Exact tests.

This work was classified as service evaluation and exempt from NHS Research Ethics Committee review.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge several colleagues from Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust for their input (Darren Parsons, Manfred Almeida, Sweenie Goonesekera and Monica Rebec), and colleagues from Public Health England (Yimmy Chow, Isidro Carrion, Bharat Patel) and the AMRHAI Reference Unit for their support. The research was partially funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance at Imperial College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or Public Health England. We also acknowledge the support of the Imperial College Healthcare Trust NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The researchers are independent from the funders. The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author Contributions

J.A.O. co-ordinated the project. M.D. performed the W.G.S. analysis; H.D., M.J.E., R.H., J.F.T., K.L.H. performed laboratory work. J.A.O., M.D., F.D., S.M., M.G., E.T.B., K.B., T.G., H.D., D.M.A., M.J.E., R.H., J.F.T. performed data analysis. N.W. and A.H.H. conceived and oversaw the study. J.A.O. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all other authors contributed equally to drafting the manuscript.

Competing Interests

JAO is a consultant to Gama Healthcare. MG attended a Pfizer advisory board in 2015. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. An ongoing national intervention to contain the spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:697–703. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canton R, et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:413–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falagas ME, Tansarli GS, Karageorgopoulos DE, Vardakas KZ. Deaths attributable to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1170–1175. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.121004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otter JA, et al. Counting the cost of an outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an economic evaluation from a hospital perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snitkin ES, et al. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:148ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monaco, M. et al. Colistin resistance superimposed to endemic carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: a rapidly evolving problem in Italy, November 2013 to April 2014. Euro Surveill19 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ah YM, Kim AJ, Lee JY. Colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nation RL, Velkov T, Li J. Colistin and Polymyxin B: Peas in a Pod, or Chalk and Cheese? Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:88–94. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giani T, et al. Large Nosocomial Outbreak of Colistin-Resistant, Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Traced to Clonal Expansion of an mgrB Deletion Mutant. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:3341–3344. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01017-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayol A, Poirel L, Villegas MV, Nordmann P. Modulation of mgrB gene expression as a source of colistin resistance in Klebsiella oxytoca. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46:108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poirel L, et al. The mgrB gene as a key target for acquired resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:75–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Formosa C, Herold M, Vidaillac C, Duval RE, Dague E. Unravelling of a mechanism of resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae using atomic force microscopy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2261–2270. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olaitan AO, et al. Worldwide emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae from healthy humans and patients in Lao PDR, Thailand, Israel, Nigeria and France owing to inactivation of the PhoP/PhoQ regulator mgrB: an epidemiological and molecular study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannatelli A, et al. MgrB inactivation is a common mechanism of colistin resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of clinical origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5696–5703. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03110-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y-Y, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Pilato V, et al. MCR-1.2: a new MCR variant encoded by a transferable plasmid from a colistin-resistant KPC carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of sequence type 512. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5612–5615. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01075-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojas, L. J. et al. Colistin Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Laboratory Detection and Impact on Mortality. Clin Infect Dis (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Li XP, et al. Clonal spread of mcr-1 in PMQR-carrying ST34 Salmonella isolates from animals in China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38511. doi: 10.1038/srep38511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xavier, B. B. et al. Identification of a novel plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene, mcr-2, in Escherichia coli, Belgium, June 2016. Euro Surveill21 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Osei Sekyere J, Govinden U, Bester LA, Essack SY. Colistin and tigecycline resistance in carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria: emerging resistance mechanisms and detection methods. J Applied Microbiol. 2016;121:601–617. doi: 10.1111/jam.13169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du H, Chen L, Tang YW, Kreiswirth BN. Emergence of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:287–288. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao X, Doi Y, Zeng L, Lv L, Liu JH. Carbapenem-resistant and colistin-resistant Escherichia coli co-producing NDM-9 and MCR-1. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:288–289. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halaby T, et al. Genomic Characterization of Colistin Heteroresistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae during a Nosocomial Outbreak. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:6837–6843. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01344-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cannatelli A, et al. In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-type carbapenemases mediated by insertional inactivation of the PhoQ/PhoP mgrB regulator. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5521–5526. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01480-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliva A, et al. Double-carbapenem regimen, alone or in combination with colistin, in the treatment of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CR-Kp) J Infect. 2017;74:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz-Price LS, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo L, et al. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science. 1997;276:250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller AK, et al. PhoQ mutations promote lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa found in colistin-treated cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5761–5769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05391-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han, J. H. et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Network of Long-Term Acute Care Hospitals. Clin Infect Dis (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Choi MJ, Ko KS. Loss of hypermucoviscosity and increased fitness cost in colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 23 strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:6763–6773. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00952-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deris ZZ, et al. The combination of colistin and doripenem is synergistic against Klebsiella pneumoniae at multiple inocula and suppresses colistin resistance in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5103–5112. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01064-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung JH, Bhat A, Kim CJ, Yong D, Ryu CM. Combination therapy with polymyxin B and netropsin against clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28168. doi: 10.1038/srep28168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onori R, et al. Tracking Nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections and Outbreaks by Whole-Genome Analysis: Small-Scale Italian Scenario within a Single Hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2861–2868. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00545-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Agamy MH, et al. Persistence of Klebsiella pneumoniae clones with OXA-48 or NDM carbapenemases causing bacteraemias in a Riyadh hospital. Diag Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76:214–216. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.PHE. Acute trust toolkit for the early detection, management and control of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/carbapenemase-producing-enterobacteriaceae-early-detection-management-and-control-toolkit-for-acute-trusts [Accessed 02/08/2017] (2013).

- 36.Wilson APR, et al. Prevention and control of multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: recommendations from a Joint Working Party. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:S1–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]