Abstract

This article provides a quantitative analysis of peer review as an emerging field of research by revealing patterns and connections between authors, fields and journals from 1950 to 2016. By collecting all available sources from Web of Science, we built a dataset that included approximately 23,000 indexed records and reconstructed collaboration and citation networks over time. This allowed us to trace the emergence and evolution of this field of research by identifying relevant authors, publications and journals and revealing important development stages. Results showed that while the term “peer review” itself was relatively unknown before 1970 (“referee” was more frequently used), publications on peer review significantly grew especially after 1990. We found that the field was marked by three development stages: (1) before 1982, in which most influential studies were made by social scientists; (2) from 1983 to 2002, in which research was dominated by biomedical journals, and (3) from 2003 to 2016, in which specialised journals on science studies, such as Scientometrics, gained momentum frequently publishing research on peer review and so becoming the most influential outlets. The evolution of citation networks revealed a body of 47 publications that form the main path of the field, i.e., cited sources in all the most influential publications. They could be viewed as the main corpus of knowledge for any newcomer in the field.

Keywords: Peer review, Journals, Authors, Citation networks, Main path

Introduction

Peer review is key to ensure rigour and quality of scholarly publications, establish standards that differentiate scientific discoveries from other forms of knowledge and maintain credibility of research inside and outside the scientific community (Bornmann 2011). Although many believe it has roots that trace back centuries ago, historical analysis indicated that the very idea and practices of peer review that are predominant today in scholarly journals are recent. Indeed, peer review developed in the post-World War II decades when the tremendous expansion of science took place and the “publish or perish” culture and their competitive symbolisms we all know definitively gained momentum (Fyfe et al. 2017). Unfortunately, although this mechanism determines resource allocation, scientist reputation and academic careers (Squazzoni et al. 2013), a large-scale quantitative analysis of the emergence of peer review as a field of research that could reveal patterns, connections and identify milestones and developments is missing (Squazzoni and Takács 2011).

This paper aims to fill this gap by providing a quantitative analysis of peer review as an emerging field of research that reveals patterns and connections between authors, fields and journals from 1950 to 2016. We collected all available sources from Web of Science (WoS) by searching for all records including “peer review” among their keywords. By using the program WoS2Pajek (Batagelj 2007), we transformed these data in a collection of networks to reconstruct citation networks and different two-mode networks, including works by authors, works by keywords and works by journals. This permitted us to trace the most important stages in the evolution of the field. Furthermore, by performing a ’main path’ analysis, we tried to identify the most relevant body of knowledge that this field developed over time.

Our effort has a twofold purpose. First, it aims to reconstruct the field by quantitatively tracking the formation and evolution of the community of experts who studied peer review. Secondly, it aims to reveal the most important contributions and their connections in terms of citations and knowledge flow, so as to provide important resources for all newcomers in the field. By recognizing the characteristics and boundaries of the field, we aim to inspire further research on this important institution, which is always under the spotlight and under attempts of reforms, often without relying on robust evidence (Edwards and Roy 2016; Squazzoni et al. 2017).

For standard theoretical notions on networks we use the terminology and definitions from Batagelj et al. (2014). All network analyses were performed using Pajek—a program for analysis and visualization of large networks (De Nooy et al. 2011).

Data

Data collection

We searched for any record containing “peer review*” in WoS, Clarivate analytics’s multidisciplinary databases of bibliographic information in May and June 2015. We obtained 17,053 hits and additional 2867 hits by searching for "refereeing". Figure 1 reports an example of records we extracted. We limited the search to the WoS core collection because for other WoS databases the CR-fields (containing citation information) could not be exported.

Fig. 1.

Record from web of science

Using WoS2Pajek (Batagelj 2007), we transformed data in a collection of networks: the citation network (from the field CR), the authorship network (from the field AU), the journalship network (from the field CR or J9), and the keywordship network (from the field ID or DE or TI). An important property of all these networks is that they share the same set—the set of works (papers, reports, books, etc.) as the first node set W. It is important to note that a citation network is based on the citing relation

Works that appear in descriptions were of two types:

Hits—works with a WoS description;

Only cited works (listed in CR fields, but not contained in the hits).

These data were stored in a partition DC: iff a work w had a WoS description; and otherwise. Another partition year contained the work’s publication year from the field PY or CR. We also obtained a vector NP: number of pages of each work w. We built a CSV file titles with basic data about works with to be used to list results. Details about the structure of names in constructed networks are provided in “The structure of names in constructed networks” section.

The dataset was updated in March 2016 by adding hits for the years 2015 and 2016. We manually prepared short descriptions of the most cited works (fields: AU, PU, TI, PY, PG, KW; but without CR data) and assigned them the value .

A first preliminary analysis performed in 2015 revealed that many works without a WoS description had large indegrees in the citation network. We manually searched for each of them (with indegree larger or equal to 20) and, when possible, we added them into the data set. It is important to note that earlier papers, which had a significant influence in the literature, did not often use the now established terminology (e.g., keywords) and were therefore overlooked by our queries.

After some iterations, we finally constructed the data set used in this paper. The final run of the program WoS2Pajek produced networks with sets of the following sizes: works , authors , journals , and keywords . In both phases, 22,981 records were collected. There were 887 duplicates (considered only once).

We removed multiple links and loops (resulting from homonyms) from the networks. The cleaned citation network had nodes and arcs.

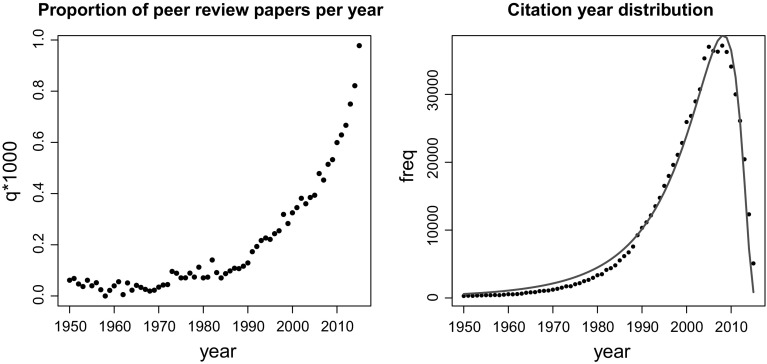

Figure 2 shows a schematic structure of a citation network. The circular nodes correspond to the query hits. The works cited in hits are presented with the triangular nodes. Some of them are in the following phase (search for often cited works) converted into the squares (found in WoS by our secondary search). They introduce new cited nodes represented as diamonds. It is important to note that the age of a work was determined by its publication year. In a citation network, in order to get a cycle, an “older” node had to cite a “younger or the same age” work. Given that this rarely happens, citation networks are usually (almost) acyclic.

Fig. 2.

Citation network structure: —circle, square; —triangle, diamond

To acyclic network’s nodes, we can assign levels such that for each arc, the level of its initial node is higher than the level of its terminal node. In an acyclic citation network, an example of a level is the publication date of a work. Therefore, acyclic networks can be visualized by levels—vertical axis representing the level with all arcs pointing in the same direction—in Fig. 2 pointing down.

In the following section, we look at some statistical properties of obtained networks.

Distributions

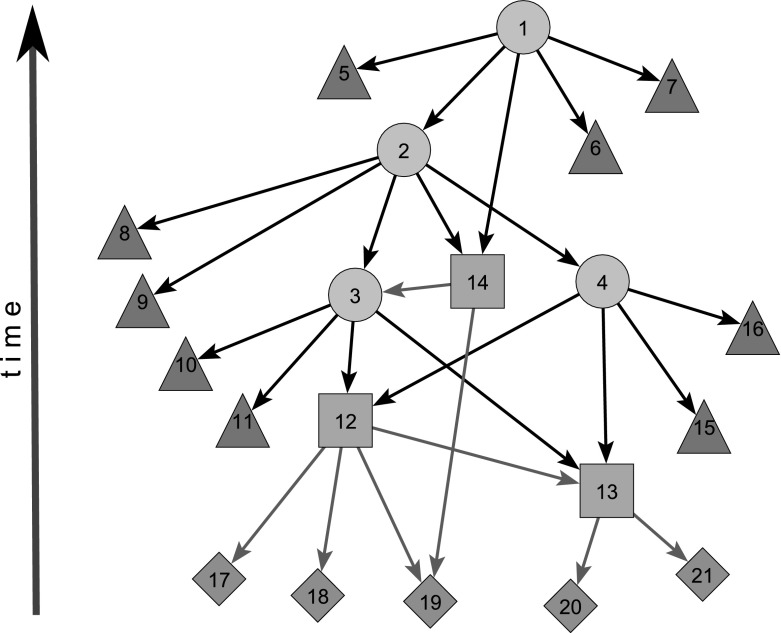

In the left panel of Fig. 3, we showed a growth of the proportion q—the number of papers on peer review divided by the total number of papers from WoS () by year. Proportions were multiplied by 1000. This means that peer review received growing interest in the literature, especially after 1990. For instance, in 1950 WoS listed only 6 works on peer review among 97,529 registered works published in that year, . In 2015, we found 2583 works on peer review among 2,641,418 registered works, .

Fig. 3.

Growth of the number of works and the citation year distribution

In the right panel of Fig. 3, the distribution of all (hits only cited) works by year is shown. It is interesting to note that this distribution can be fitted by log normal distribution (Batagelj et al. 2014, pp. 119–121):

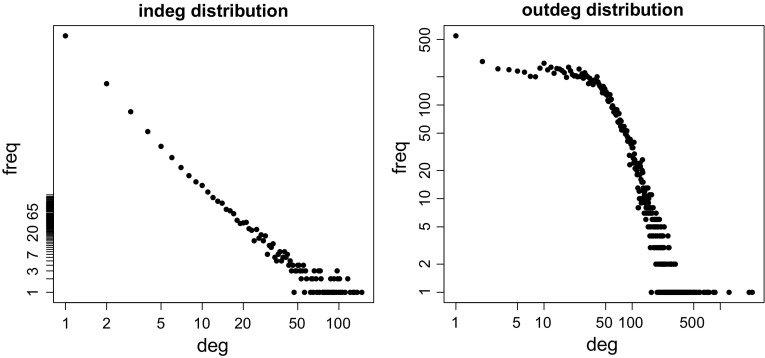

Figure 4 shows indegree and outdegree distributions in the citation network in double logarithmic scales. Interestingly, indegrees show a scale-free property. It is somehow surprising that frequencies of outdegrees in the range [3, 42] show an almost constant value—they are in the range [215, 328]. works with the largest indegrees are the most cited papers.

Fig. 4.

Degree distributions in the citation network

Table 1 shows the 31 most cited works. Eight works, including the number 1, were cited for methodological reasons, not dealing with peer review. As expected, most of the top cited works were published earlier, with only eight published after 2000. We also searched for the most cited books. We found 15 books cited (number in parentheses) more than 50 times: (52) Kuhn, T: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 1962; (57) Glaser, BG, Strauss, AI: The Discovery of Grounded Theory, 1967; (67) Merton, RK: The Sociology of Science, 1973; (97) Lock, S: A Difficult Balance, 1985; (72) Hedges, LV, Olkin, I: Statistical methods for meta-analysis, 1985; (173) Cohen, J: Statistical power analysis, 1988; (87) Chubin, D, Hackett, EJ: Peerless Science, 1990; (60) Boyer, EL: Scholarship reconsidered, 1990; (51) Daniel, H-D: Guardians of science, 1993; (55) Miles, MB, Huberman, AM: Qualitative data analysis, 1994; (64) Gold, MR, et al.: Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine, 1996; (53) Lipsey, MW, Wilson, DB: Practical meta-analysis, 2001; (58) Weller, AC: Editorial peer review, 2001; (69) Higgins, JPT, Green, S: Systematic reviews of interventions, 2008; (130) Higgins, JPT, Green, S: Systematic reviews of interventions, 2011.

Table 1.

Most cited works

| n | Freq | First author | Year | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 173 | Cohen, J | 1988 | Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge |

| 2 | 164 | Peters, DP | 1982 | Peer-review practices of psychological journals—the fate of...Behav Brain Sci |

| 3 | 151 | Egger, M | 1997 | Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Brit Med J |

| 4 | 150 | Stroup, DF | 2000 | Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology—a proposal for reporting. JAMA |

| 5 | 135 | Dersimonian, R | 1986 | Metaanalysis in clinical-trials. Control Clin Trials |

| 6 | 130 | Zuckerma, H | 1971 | Patterns of evaluation in science—institutionalisation, structure and functions of referee system. Minerva |

| 7 | 130 | Higgins, JPT | 2011 | Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane |

| 8 | 126 | Moher, D | 2009 | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Plos Med |

| 9 | 125 | Higgins, JPT | 2003 | Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Brit Med J |

| 10 | 121 | Cicchetti, DV | 1991 | The reliability of peer-review for manuscript and grant submissions...Behav Brain Sci |

| 11 | 119 | Hirsch, JE | 2005 | An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci Usa |

| 12 | 114 | Mahoney, M | 1977 | Publication prejudices: an experimental study of confirmatory bias...cognitive therapy and research |

| 13 | 114 | van Rooyen, S | 1999 | Effect of open peer review on quality of reviews and on reviewers’ recommendations:...Brit Med J |

| 14 | 114 | Easterbrook, PJ | 1991 | Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet |

| 15 | 110 | Landis, JR | 1977 | Measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics |

| 16 | 109 | Godlee, F | 1998 | Effect on the quality of peer review of blinding reviewers and asking them to sign their reports—...JAMA |

| 17 | 108 | Horrobin, DF | 1990 | The philosophical basis of peer-review and the suppression of innovation. JAMA |

| 18 | 107 | Moher, D | 2009 | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: PRISMA. Ann Intern Med |

| 19 | 107 | Jadad, AR | 1996 | Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials |

| 20 | 105 | Mcnutt, RA | 1990 | The effects of blinding on the quality of peer-review—a randomized trial. JAMA |

| 21 | 104 | Cole, S | 1981 | Chance and consensus in peer-review. Science |

| 22 | 103 | Moher, D | 1999 | Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: QUOROM. Lancet |

| 23 | 98 | Justice, AC | 1998 | Does masking author identity improve peer review quality?—a randomized controlled trial. JAMA |

| 24 | 97 | Lock, S | 1985 | A difficult balance: editorial peer review in medicine. Nuffield Trust |

| 25 | 95 | van Rooyen, S | 1998 | Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer review—a randomized trial. JAMA |

| 26 | 92 | Black, N | 1998 | What makes a good reviewer and a good review for a general medical journal? JAMA |

| 27 | 91 | Scherer, RW | 1994 | Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts—a metaanalysis. JAMA |

| 28 | 90 | Higgins, JPT | 2002 | Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med |

| 29 | 90 | Smith, R | 2006 | Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J Roy Soc Med |

| 30 | 87 | Goodman, SN | 1994 | Manuscript quality before and after peer-review and editing at annals of internal-medicine. Ann Intern Med |

| 31 | 87 | Chubin, D | 1990 | Peerless science: peer review and US science policy. SUNY Press |

We also found that works having the largest outdegree (the most citing works) were usually overview papers. These papers have been mostly published recently (in the last ten years). Among the first 50 works that cited works on peer review most frequently, only two were published before 2000—one in 1998 and another one in 1990. However, none of them were on peer review and so we did not report them here.

The boundary problem

Considering the indegree distribution in the citation network , we found that most works were referenced only once. Therefore, we decided to remove all ‘only cited’ nodes with indegree smaller than 3 ( and )—the boundary problem (Batagelj et al. 2014). We also removed all only cited nodes starting with strings “[ANONYM”, “WORLD_”, “INSTITUT_”, “U_S”, “*US”, “WHO_”, “*WHO”, “WHO(”. “AMERICAN_”, “DEPARTME_”, “*DEP”, “NATIONAL_”, “UNITED_”, “CENTERS_”, “INTERNAT_”, “EUROPEAN_”. The final ‘bounded’ set of works included 45,917 works.

Restricting two-mode networks , and to the set and removing from their second sets nodes with indegree 0, we obtained basic networks , and with reduced sets with the following size , , .

Unfortunately, some information (e.g., co-authors, keywords) was available only for works with a WoS full description. In these cases, we limited our analysis to the set of works with a description

Its size was . By restricting basic networks to the set , we obtained subnetworks , and .

It is important to note that we obtain a temporal network if the time is attached to an ordinary network. is a set of time points . In a temporal network, nodes and links are not necessarily present or active in all time points. The node activity sets T(v) and link activity sets T(l) are usually described as a sequence of time intervals. If a link l(u, v) is active in a time point t then also its endnodes u and v should be active in the time point t. The time is usually either a subset of integers, , or a subset of reals, .

We denote a network consisting of links and nodes active in time, , by and call it the (network) time slice or footprint of t. Let (for example, a time interval). The notion of a time slice is extended to by: a time slice for is a network consisting of links and nodes of active at some time point .

Here, we presented a simple analysis of changes of sets of main authors, main journals and main keywords through time (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5). Our analysis was based on temporal versions of subnetworks , and —the activity times were determined by the publication year of the corresponding work.

Table 2.

Left: authors with the largest number of works ( indeg), Right: authors with the largest contribution to the field (weighted indegree in normalized )

| n | Works | Author | Value | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | BORNMANN_L | 29.1167 | BORNMANN_L |

| 2 | 59 | ALTMAN_D | 21.7833 | DANIEL_H |

| 3 | 55 | SMITH_R | 18.2453 | SMITH_R |

| 4 | 55 | LEE_J | 18.0105 | ALTMAN_D |

| 5 | 50 | MOHER_D | 17.7255 | MARSHALL_E |

| 6 | 48 | DANIEL_H | 17.0000 | GARFIELD_E |

| 7 | 46 | SMITH_J | 15.3788 | SMITH_J |

| 8 | 38 | CURTIS_K | 15.1737 | RENNIE_D |

| 9 | 36 | BROWN_D | 14.6538 | SQUIRES_B |

| 10 | 36 | RENNIE_D | 14.5636 | CHENG_J |

| 11 | 35 | LEE_S | 13.8833 | THOENNES_M |

| 12 | 32 | WANG_J | 13.7957 | COHEN_J |

| 13 | 32 | WILLIAMS_J | 13.2898 | JOHNSON_C |

| 14 | 31 | THOENNES_M | 13.2857 | REYES_H |

| 15 | 29 | JOHNSON_C | 12.9779 | LEE_J |

| 16 | 29 | JOHNSON_J | 12.6667 | WELLER_A |

| 17 | 29 | REYES_H | 11.9167 | BJORK_B |

| 18 | 28 | ZHANG_Y | 11.1648 | BROWN_D |

| 19 | 28 | WANG_Y | 10.9091 | BROWN_C |

| 20 | 27 | ZHANG_L | 10.5000 | MERVIS_J |

| 21 | 27 | SMITH_M | 10.3762 | CALLAHAM_M |

| 22 | 27 | WILLIAMS_A | 10.2952 | JONES_R |

| 23 | 27 | CASTAGNA_C | 10.2198 | MOHER_D |

| 24 | 25 | COHEN_J | 10.0000 | HARNAD_S |

| 25 | 25 | HELSEN_W | 10.0000 | BEREZIN_A |

Table 3.

Main authors through time

| –1970 | 1971–1980 | 1981–1990 | 1991–2000 | 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | CLARK_G | 6 | WEINSTEI_P | 13 | SQUIRES_B | 19 | RENNIE_D | 13 | BENNINGE_M | 34 | BORNMANN_L | 36 | LEE_J |

| 12 | FISHER_H | 6 | MILGROM_P | 8 | CHALMERS_T | 16 | SMITH_R | 13 | SMITH_R | 30 | DANIEL_H | 31 | BROWN_D |

| 9 | MILSTEAD_K | 6 | RATENER_P | 8 | COHEN_L | 12 | REYES_H | 12 | ALTMAN_D | 26 | ALTMAN_D | 25 | ZHANG_L |

| 9 | SMITH_J | 6 | MORRISON_K | 7 | CHUBIN_D | 11 | MARSHALL_E | 12 | JOHNSON_J | 20 | HELSEN_W | 25 | LEE_S |

| 8 | WILEY_F | 6 | ZUCKERMA_H | 5 | GARFIELD_E | 9 | LUNDBERG_G | 11 | CASTAGNA_C | 18 | ANDERSON_P | 24 | WANG_J |

| 8 | REINDOLL_W | 5 | HULKA_B | 5 | LOCK_S | 9 | KOSTOFF_R | 10 | RUBEN_R | 17 | RESNICK_D | 24 | CURTIS_K |

| 8 | GRIFFIN_E | 5 | READ_W | 5 | HARGENS_L | 9 | JOHNSON_D | 10 | KENNEDY_D | 17 | MOHER_D | 23 | BORNMANN_L |

| 8 | ROBERTSO_A | 5 | GARFIELD_E | 5 | RENNIE_D | 8 | BERO_L | 9 | YOUNG_E | 17 | KAISER_M | 23 | MAZEROLL_S |

| 7 | ALFEND_S | 4 | MERTON_R | 5 | MARSHALL_E | 8 | COHEN_J | 9 | WEBER_P | – | 23 | WANG_Y | |

| 7 | SALE_J | 4 | WALSH_J | 5 | SMITH_H | 8 | FLETCHER_R | 9 | JACKLER_R | 12 | CURTIS_K | 19 | THOENNES_M |

| 7 | MARSHALL_C | – | – | 8 | HAYNES_R | 9 | JOHNS_M | 11 | THOENNES_M | 19 | WANG_H | ||

| 6 | HALVORSO_H | 2 | CHUBIN_D | 3 | LUNDBERG_G | 8 | RUBIN_H | 9 | SATALOFF_R | 10 | LEE_J | 19 | MOHER_D |

| 6 | CAROL_J | 2 | CHALMERS_T | 8 | FLETCHER_S | 8 | D’OTTAVI_S | 9 | CASTAGNA_C | – | |||

| – | 8 | KHUDER_S | 8 | MOHER_D | 9 | SMITH_R | 13 | ALTMAN_D | |||||

| 4 | GARFIELD_F | – | 8 | WEBER_R | 13 | SMITH_R | |||||||

| 2 | MERTON_R | 7 | ALTMAN_D | – | |||||||||

| 6 | SQUIRES_B | 5 | DANIEL_H | ||||||||||

| 5 | MOHER_D | 5 | REYES_H | ||||||||||

| 4 | BORNMANN_L | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RENNIE_D |

Table 4.

Main journals ( indeg)

| n | Number | Journal | n | Number | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 515 | BMJ OPEN | 21 | 66 | ANN PHARMACOTHER |

| 2 | 288 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC | 22 | 64 | NEW ENGL J MED |

| 3 | 177 | PLOS ONE | 23 | 62 | CUTIS |

| 4 | 175 | NATURE | 24 | 59 | ANN ALLERG ASTHMA IM |

| 5 | 174 | SCIENTOMETRICS | 25 | 59 | BEHAV BRAIN SCI |

| 6 | 174 | BRIT MED J | 26 | 59 | PEDIATRICS |

| 7 | 165 | SCIENCE | 27 | 57 | CHEM ENG NEWS |

| 8 | 127 | ***** | 28 | 57 | MED J AUSTRALIA |

| 9 | 102 | ACAD MED | 29 | 54 | J GEN INTERN MED |

| 10 | 98 | LANCET | 30 | 53 | MATER TODAY-PROC |

| 11 | 92 | SCIENTIST | 31 | 53 | J SCHOLARLY PUBL |

| 12 | 91 | LEARN PUBL | 32 | 53 | J NANOSCI NANOTECHNO |

| 13 | 81 | J AM COLL RADIOL | 33 | 53 | AM J PREV MED |

| 14 | 80 | PHYS TODAY | 34 | 52 | BMC PUBLIC HEALTH |

| 15 | 78 | ARCH PATHOL LAB MED | 35 | 50 | J SEX MED |

| 16 | 78 | J UROLOGY | 36 | 50 | J SPORT SCI |

| 17 | 75 | J ASSOC OFF AGR CHEM | 37 | 50 | MED EDUC |

| 18 | 73 | CAN MED ASSOC J | 38 | 48 | RES EVALUAT |

| 19 | 71 | ANN INTERN MED | 39 | 48 | BRIT J SPORT MED |

| 20 | 67 | ABSTR PAP AM CHEM S | 40 | 47 | PROCEDIA ENGINEER |

Table 5.

Main journals through time

| –1970 | 1971–1980 | 1981–1990 | 1991–2000 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | J ASSOC OFF AGR CHEM | 24 | SCIENCE | 46 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC | 126 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC |

| 21 | LANCET | 20 | MED J AUSTRALIA | 42 | SCIENCE | 71 | NATURE |

| 15 | BRIT MED J | 18 | NEW ENGL J MED | 33 | BEHAV BRAIN SCI | 66 | BRIT MED J |

| 9 | PHYS TODAY | 16 | AM J PSYCHIAT | 32 | PHYS TODAY | 45 | SCIENCE |

| 7 | SCIENCE | 15 | PHYS TODAY | 29 | NATURE | 39 | ANN INTERN MED |

| 6 | J ASSOC OFF ANA CHEM | 11 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC | 27 | NEW ENGL J MED | 38 | LANCET |

| 4 | J AM OIL CHEM SOC | 10 | HOSP COMMUNITY PSYCH | 27 | SCIENTIST | 29 | CAN MED ASSOC J |

| 4 | YALE LAW J | 10 | FED PROC | 25 | BRIT MED J | 28 | SCIENTIST |

| 3 | NATURE | 10 | BRIT MED J | 19 | CAN MED ASSOC J | 26 | BEHAV BRAIN SCI |

| 3 | BRIT J SURG | 9 | NATURE | 16 | PROF PSYCHOL | 25 | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 3 | AM SOCIOL | 9 | AM SOCIOL | 13 | SCI TECHNOL HUM VAL | 23 | ACAD MED |

| 7 | NEW YORK STATE J MED | 13 | S AFR MED J | 23 | J ECON LIT | ||

| 7 | MED CARE | 12 | HOSPITALS | – | |||

| – | 12 | PHYS TODAY | |||||

| 9 | LANCET | 9 | NEW ENGL J MED | ||||

| 6 | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC | 44 | SCIENTOMETRICS | 489 | BMJ OPEN | ||

| 40 | CUTIS | 33 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC | 146 | PLOS ONE | ||

| 32 | BRIT MED J | 31 | J SEX MED | 78 | SCIENTOMETRICS | ||

| 28 | LEARN PUBL | 27 | PLOS ONE | 73 | J AM COLL RADIOL | ||

| 26 | NATURE | 27 | J NANOSCI NANOTECHNO | 53 | MATER TODAY-PROC | ||

| 24 | ABSTR PAP AM CHEM S | 27 | ACAD MED | 47 | PROCEDIA ENGINEER | ||

| 23 | ACAD MED | 25 | SCIENTIST | 47 | PROCEDIA COMPUT SCI | ||

| 22 | J PROSTHET DENT | 25 | J UROLOGY | 43 | ARCH PATHOL LAB MED | ||

| 22 | ANN ALLERG ASTHMA IM | 23 | LEARN PUBL | 41 | BMC PUBLIC HEALTH | ||

| 18 | SCIENTOMETRICS | 23 | J SPORT SCI | 30 | BMC HEALTH SERV RES | ||

| 16 | J UROLOGY | 23 | ARCH PATHOL LAB MED | 30 | J ATHL TRAINING | ||

| 16 | MED EDUC | 21 | NATURE | 30 | AM J PREV MED | ||

| – | – | 29 | ACAD MED | ||||

| 14 | LANCET | 19 | CUTIS | – | |||

| 13 | SCIENCE | 19 | MED EDUC | 24 | LEARN PUBL | ||

| 12 | SCIENTIST | 19 | SCIENCE | 23 | JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC | ||

| 16 | BRIT MED J | 19 | BMJ-BRIT MED J | ||||

Because of an increasing growth of interest (see the left panel of Fig. 3) on peer review, we decided to split the time line into intervals [1900, 1970], [1971, 1980], [1981, 1990], [1991, 2000], [2001, 2005], [2006, 2010], [2011, 2015].

Most cited works, main works, journals and keywords

The left panel of Table 2 shows the authors with the largest number of co-authored works ( indegree), while the right panel shows the authors with the largest fractional contribution of works (weighted indegree in the normalized ). If we compare authors from Table 2 with the list of the most cited works in Table 1, we see that the two rankings are very different. Only three out of 25 authors with the largest number of works published a work that is on the list of 31 the most cited works. These are J. Cohen, D. Moher with two publications, and R. Smith. This is in line with the classic study by Cole and Cole (1973) in which they analyzed several aspects of the communication process in science. They used bibliometric data and survey data of the university physicists to study the conditions making for high visibility od scientist’s work. They found four determinants of visibility: the quality of work measured by citations, the honorific awards received for their work, the prestige of their departments and specialty. In short, quantity of outputs had no effect on visibility. We did not check each listed author’s name for homonymity.

In order to calculate the author’s contribution that is shown in Table 2, we used the normalized authorship network . A contribution of each paper p was equal to . Because we did not have information about each author’s real contribution, we used the so called fractional approach (Gauffriau et al. 2007; Batagelj and Cerinšek 2013) and set

This means that the contribution of an author v to the field is equal to its weighted indegree

Table 2 shows the authors who contributed more to the field of “peer review”. Comparing both panels of Table 2, it is possible to observe, for example, that L. Bornmann contributed to the papers he co-authored as he collaborated with other researchers in the field. Vice-versa, for example, E. Marshall (indeg ) and E. Garfield (indeg ) mostly contributed to the field as single authors and so appeared higher in the right panel of Table 2.

The first rows of Table 3 indicate the top authors in each time interval. If we restrict our attention to the authors who remained in the leading group at least for two time periods, we found a sequence starting from R. Merton (–1980) and E. Garfield (–1990), followed by D. Chubin and T. Chalmers (1971–1990), B. Squires, E. Marshall and G. Lundberg (1981–2000), and D. Rennie (1981–2005) and H. Reyes (1991–2005). D. Altman, R. Smith and D. Moher remained in the leading group for four periods (1991–2015). C. Castagna and H. Daniel were very active in the period (2001–2010). Later, the leading authors were L. Bornmann (2001–2015), M. Thoennessen, J. Lee, and K. Curtis (2006–2015).

The short names ambiguity problem started to emerge with the growth of number of different authors in the period 1991–2000 with Smith_R (R, RD, RA, RC) and Johnson_D (DM, DAW, DR, DL). In 2006–2015, we found an increasing presence of Chinese (and Korean) authors: Lee_J, Zhang_L, Lee_S, Wang_J, Wang_Y, and Wang_H. Because of the “three Zhang, four Li” effect (100 most common Chinese family names were shared by 85% of the population, Wikipedia (2016) all these names represent groups of authors. For example: Lee_J (Jaegab, Jaemu, Jae Hwa, Janette, Jeong Soon, Jin-Chuan, Ji-hoon, Jong-Kwon, Joong, Joseph, Joshua,Joy L, Ju, Juliet, etc.) and Zhang_L (L X, Lanying, Lei, Li, Lifeng, Lihui, Lin, Lina, Lixiang, Lujun).

More interestingly, our analysis showed that researchers in medicine were more active in studying peer review, though this can be simply due to the larger size of this community. Out of 47 top journals publishing papers on peer review, 23 journals were listed in medicine (see Table 4). Among these top journals, there are also Nature, Science, Scientist, but also specialized journals on science studies such as Scientometrics. The third one on the list is a rather new (from 2006) open access scientific journal, that is, PLoS ONE.

Table 5 indicates that the first papers on the “peer review” were published in chemistry, physics, medicine, sociology and general science journals. Some of these remained among leading journals on “peer review” also in the following periods: Phys Today (–2000), Lancet (–2005), Science, Nature (–2010), and Brit Med J (–2015). In the period (1971–1980) two medical journals New Eng J Med (1971–2000) and JAMA (1971–2015) joined the leading group. JAMA was in the period (1981–2005) the main journal. In this period, most of the leading outlets were medicine journals. In the period (1981–1990), Scientometrics (1981–2015) and Scientist (1981–2010) significantly contributed. In the period (2006–2010), Scientometrics was the main journal and PLoS ONE entered the picture of the leading group, joined in the period (2011–2015) by BMJ Open. Together with Scientometrics, these two journals were the most prolific in publishing research on peer review, whereas in the period (2011–2015), Science, Nature, JAMA, BMJ and Learn Pub disappeared from the top.

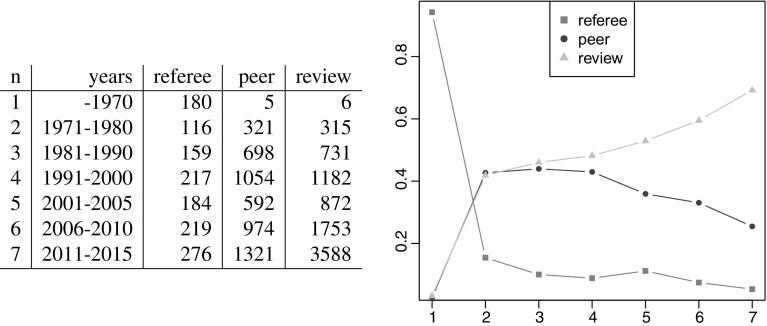

We also analyzed the main keywords (keywords in the papers and words in the titles). While obviously ’review’ and ’peer’ were top keywords, other more familiar in medicine appeared frequently, such as medical, health, medicine, care, patient, therapy, clinical, disease, cancer and surgery as did trial, research, quality, systematic, journal, study and analysis. More importantly, it is interesting to note that ’refereeing’ initially prevailed over ’peer review’, which became more popular later (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Referee: peer: review

Citations

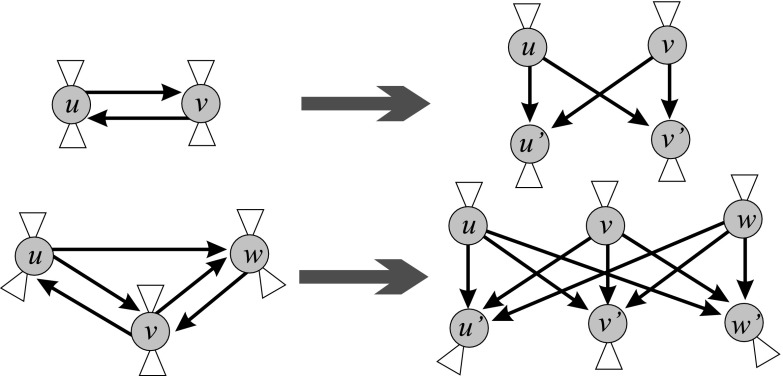

A citation network is usually (almost) acyclic. In the case of small strong components (cyclic parts) it can be transformed into a corresponding acyclic network using the preprint transformation. The preprint transformation replaces each work u from a strong component by a pair: published work u and its preprint version . A published work could cite only preprints. Each strong component was replaced by a corresponding complete bipartite graph on pairs—see Fig. 6 and Batagelj et al. (2014, p. 83). We determined the importance of arcs (citations) and nodes (works) using SPC (Search Path Count) weights which require an acyclic network as input data. Using SPC weights, we identified important subnetworks using different methods: main path(s), cuts and islands. Details will be given in the following subsections. Alternative approches have been proposed by Eck and Waltman (2010, 2014); Leydesdorff and Ahrweiler (2014).

Fig. 6.

Preprint transformation

We first restricted the original citation network to its ‘boundary’ (45,917 nodes). This network, , had one large weak component (39,533 nodes), 155 small components (the largest of sizes 191, 46, 32, 31, 18), and 5589 isolated nodes. The isolated nodes correspond to the works with WoS description, not connected to the rest of the network, and citing only works that were cited at most twice—and therefore were removed from the network .

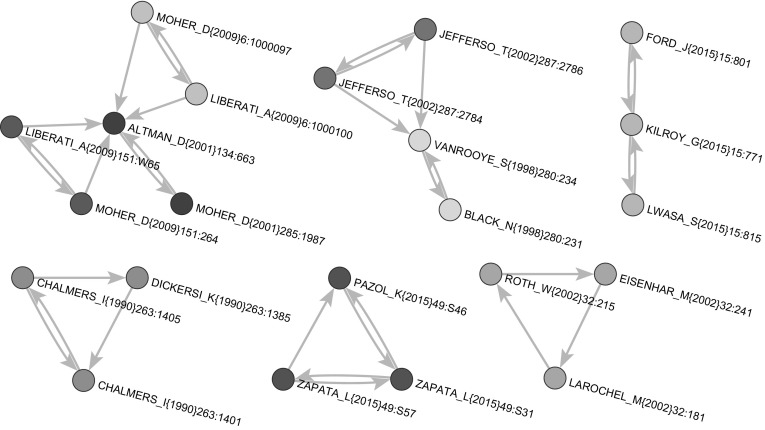

The network includes also 22 small strong components (4 of size 3 and 18 of size 2). Figure 7 shows selected strong components. In order to apply the SPC method, we transformed the citation network in an acyclic network, , using the preprint transformation. In order to make it connected, we added a common source node s and a common sink node t (see Fig. 8). The network has nodes and arcs.

Fig. 7.

Selected strong components

Fig. 8.

Search path count method (SPC)

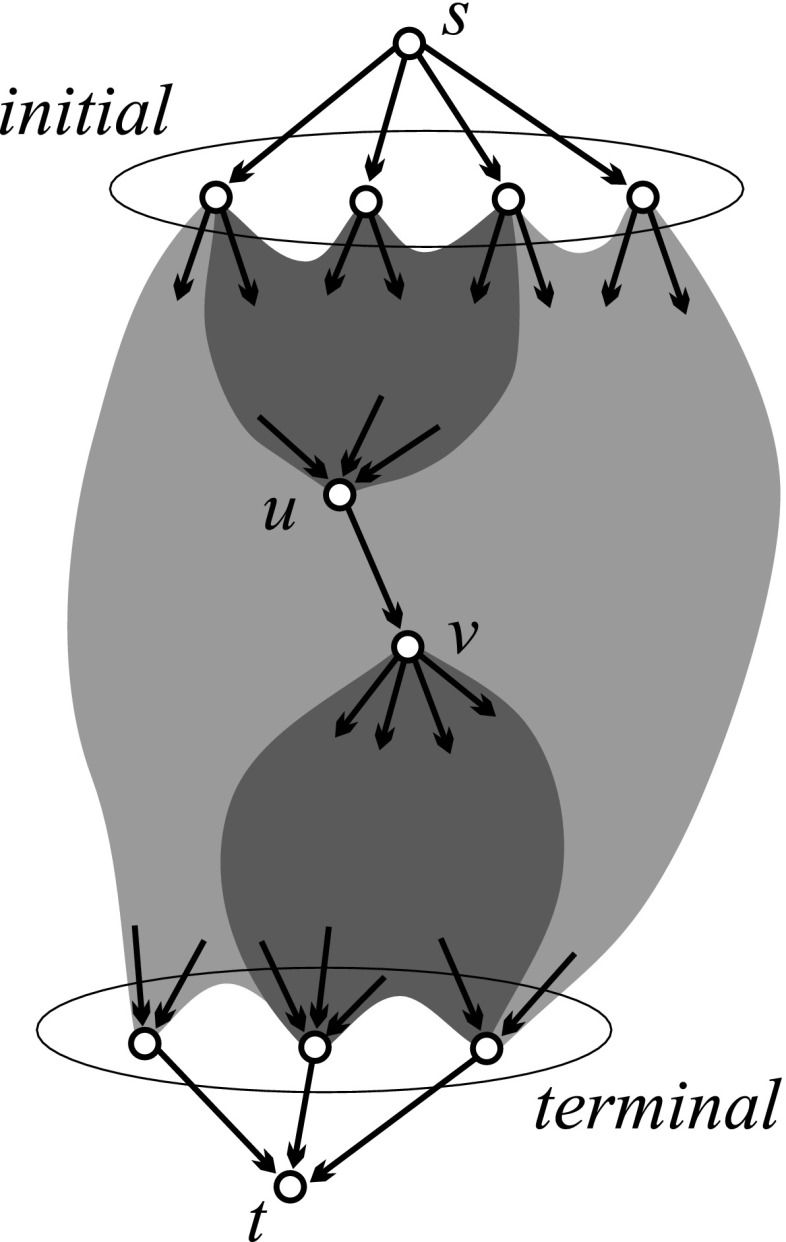

Search path count method (SPC)

The search path count (SPC) method (Hummon and Doreian 1989) allowed us to determine the importance of arcs (and also nodes) in an acyclic network based on their position. It calculates counters n(u, v) that count the number of different paths from some initial node (or the source s) to some terminal node (or the sink t) through the arc (u, v). It can be proved that all sums of SPC counters over a minimal arc cut-set give the same value F—the flow through the network. Dividing SPC counters by F, we obtain normalized SPC weights

that can be interpreted as the probability that a random s-t path passes through the arc (u, v) (see Batagelj (2003) and Batagelj et al. (2014, pp. 75–81); this method is available in the program Pajek).

In the network , the normalized SPC weights were calculated. On their basis the main path, the CPM path, main paths for 100 arcs with the largest SPC weights (“Main paths” section), and link islands [20,200] (“Cuts and islands” section) were determined.

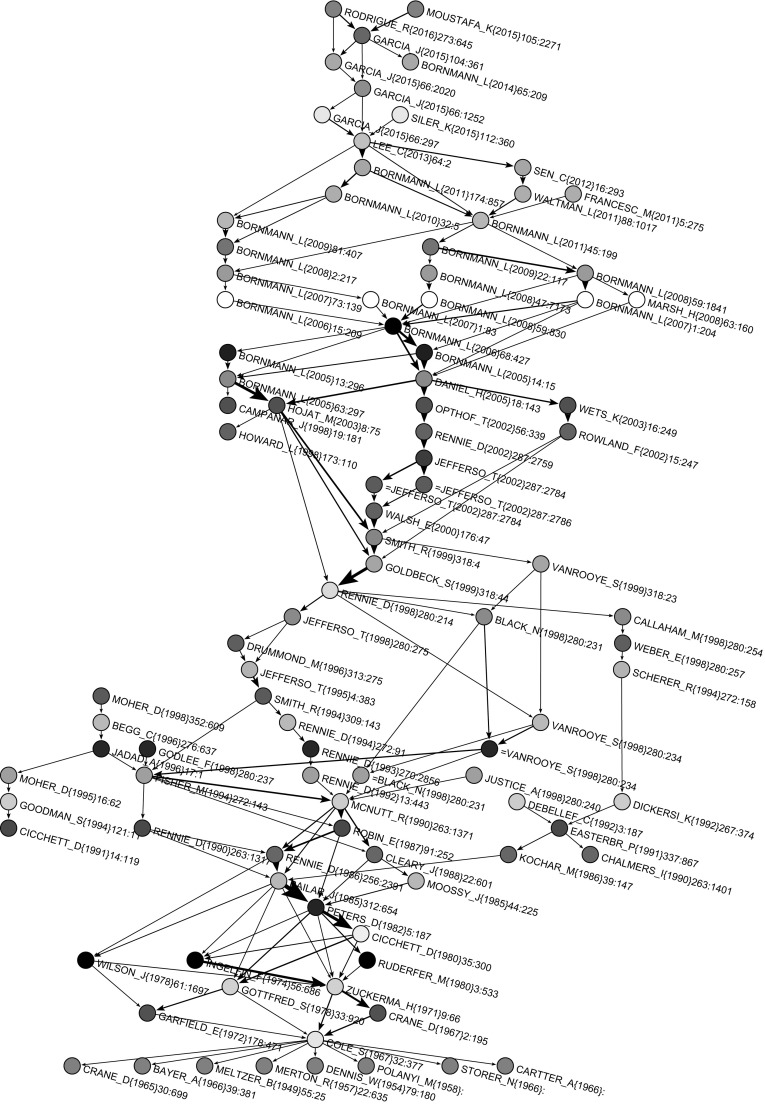

Main paths

In order to determine the important subnetworks based on SPC weights, Hummon and Doreian (1989) proposed the main path method. The main path starts in a link with the largest SPC weight and expands in both directions following the adjacent new link with the largest SPC weight. The CPM path is determined using the Critical Path Method from Operations Research (the sum of SPC weights on a path is maximal).

A problem with both main path methods is that they are unable to detect parallel developments and branchings. In July 2015 a new option was added to the program Pajek:

with several suboptions for computing local and global main paths and for searching for Key-Route main path in acyclic networks (Liu and Lu 2012). Here, the procedure begins with a set of selected seed arcs and expands them in both directions as in the main path procedure.

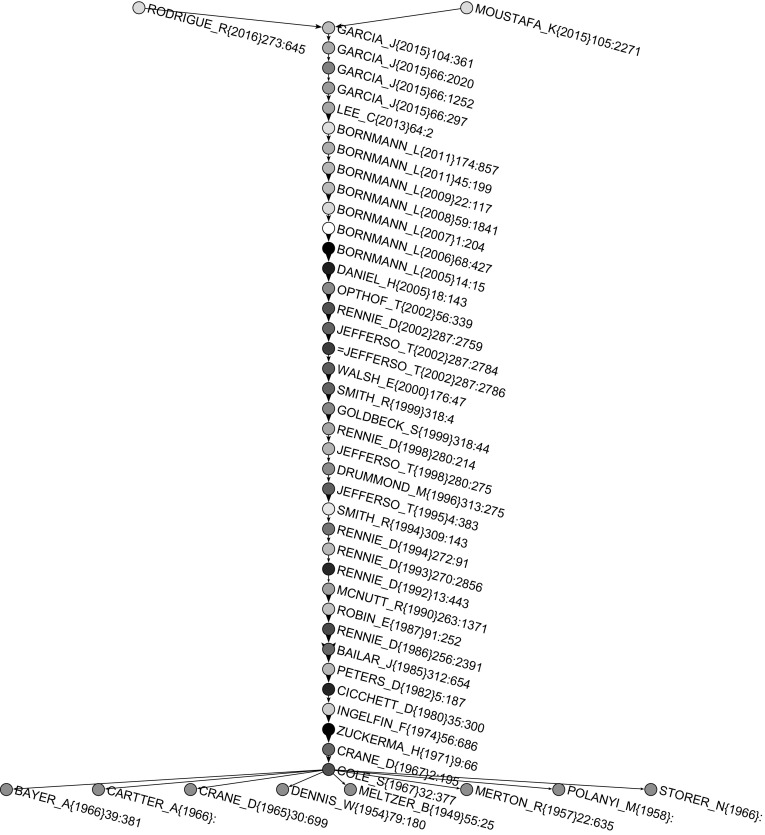

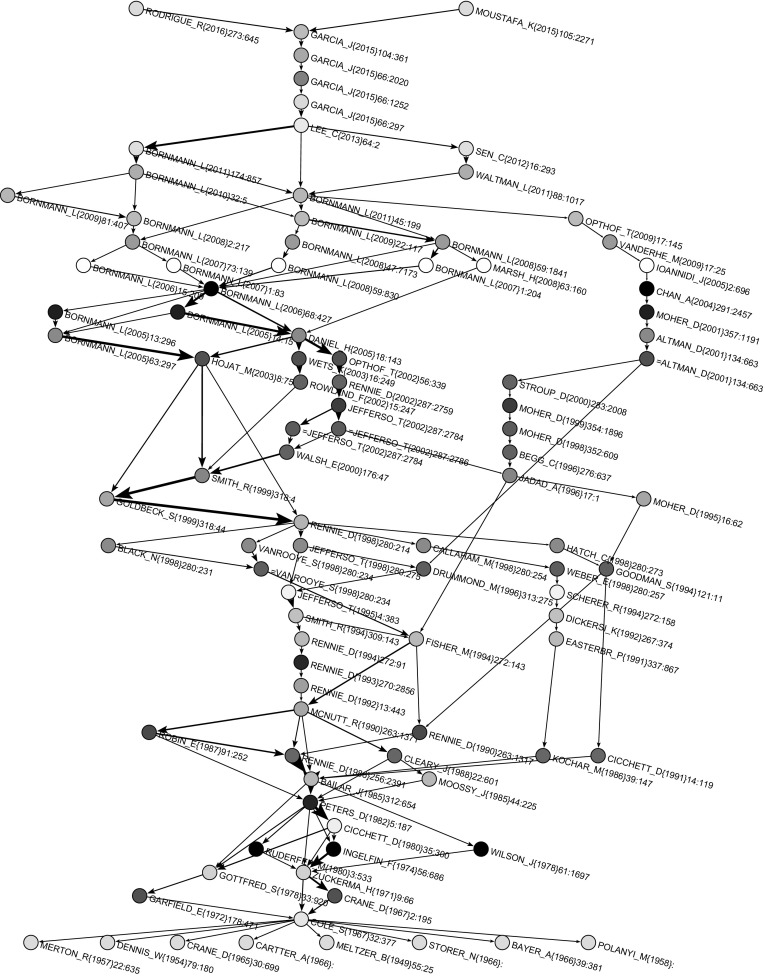

Both main path and CPM procedure gave the same main path network presented in Fig. 9. Nodes with a name starting with = (for axample =JEFFERSO_T(2002)287-2786 in Fig. 9) correspond to a preprint version of a paper. In Fig. 10, main paths for 100 seed arcs with the largest SPC weights are presented. The main path was included in this subnetwork and there were additional 47 works on parallel paths. Many of these additional works were from authors of the main path (e.g., Rennie, Cicchetti, Altman, Bornmann, Opthof). It is interesting that Moher’s publications appear on main paths four times. He is also among the most cited authors and among authors who had the highest number of publications, but he did not appear on the main path.

Fig. 9.

Main path

Fig. 10.

Main paths for 100 largest weights

Main path publication pattern

Our analysis found 48 works on the main path. After looking at all these works in detail, we classified them into three groups determined by their time periods:

Before 1982: this includes works published mostly in social science and philosophy journals and social science books;

From 1983 to 2002: this includes works published almost exclusively in biomedical journals;

From 2003: this includes works published in specialized science studies journals.

The main path till 1982

This period includes important social science journals, such as American Journal of Sociology, American Sociologist, American Psychologist and Sociology of Education, and three foundational books. The most influential authors were: Meltzer (1949), Dennis (1954), Merton (1957), Polany (1958), Crane (1965, 1967), Bayer and Folger (1966), Storer (1966), Cartter (1966), Cole and Cole (1967), Zuckerman and Merton (1971), Ingelfinger (1974), Cicchetti (1980), and Peters and Ceci (1982). The most popular topics were: scientific productivity, bibliographies, knowledge, citation measures as measures of scientific accomplishment, scientific output and recognition, evaluation in science, referee system, journal evaluation, peer-evaluation system, review process, peer review practices.

The main path from 1983 to 2002

This period includes biomedical journals, mainly JAMA. It is worth noting that JAMA published many papers which were presented at the International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication since 1986. Among the more influential authors were: Rennie (1986, 1992, 1993, 1994, 2002), Smith (1994, 1999), and Jefferson with his collaborators Demicheli, Drummond, Smith, Yee, Pratt, Gale, Alderson, Wager and Davidoff (1995, 1998, 2002). The most popular topics were: the effects of blinding on review quality, research into peer review, guidelines for peer reviewing, monitoring the peer review performance, open peer review, bias in peer review system, measuring the quality of editorial peer review, development of meta-analysis and systematic reviews approaches.

The main path from 2003

Here, the situation changed again. Some specialized journals on science studies gained momentum, such as Scientometrics, Research Evaluation, Journal of Informetrics and JASIST. The most influential authors were: Bornmann and Daniel (2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011) and Garcia, Rodriguez-Sanchez and Fdez-Valdivia (4 papers in 2015, 2016). Others popular publications were Lee et al. (2013) and Moustafa (2015). Research interest went to peer review of grant proposals, bias, referee selection and editor-referee/author links.

Cuts and islands

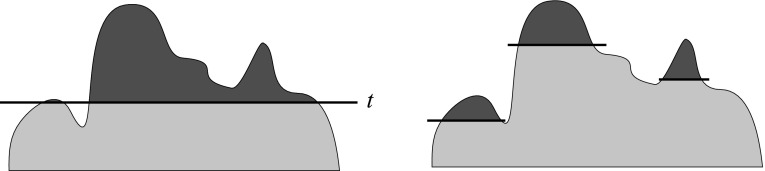

Cuts and islands are two approaches to identify important groups in a network. The importance is expressed by a selected property of nodes or links.

If we represent a given or computed property of nodes/links as a height of nodes/links and we immerse the network into a water up to a selected property threshold level, we obtain a cut (see the left picture in Fig. 11). By varying the level, we can obtain different islands—maximal connected subnetwork such that values of selected property inside island are larger than values on the island’s neighbors and the size (number of island’s nodes) is within a given range [k, K] (see the right picture in Fig. 11). An island is simple iff it has a single peak [for details, see (Batagelj et al. 2014, pp. 54–61)].

Fig. 11.

Cuts and islands

Zaveršnik and Batagelj (2004) developed very efficient algorithms to determine the islands hierarchy and list all the islands of selected sizes. They are available in Pajek.

Islands allow us also to overcome a typical problem of the main path approach, that is the selection of seed arcs. Here, we simply determined all islands and looked at the maximal SPC weight in each island. This allowed us to determine the importance of an island.

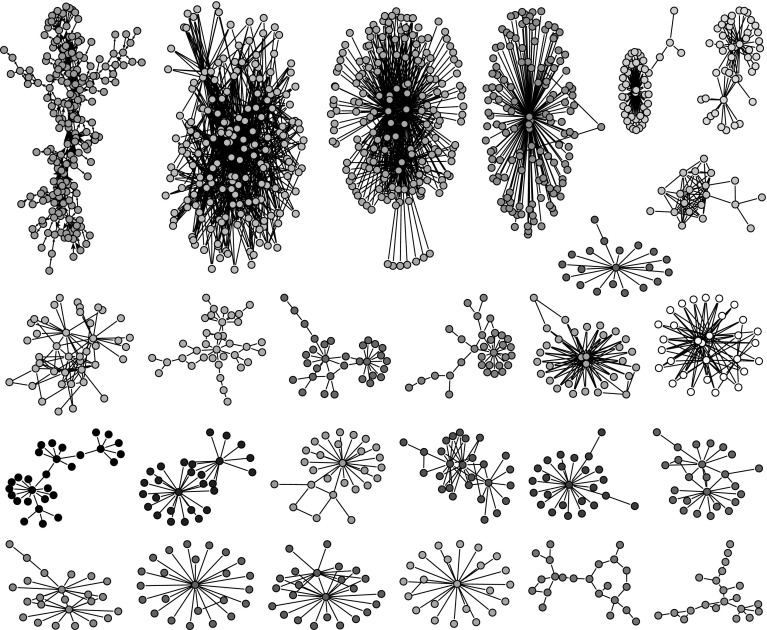

When searching for SPC link islands for the number of nodes between 20 and 200 (and between 20 and 100), we found 26 link islands (see Fig. 12). Many of these islands have a very short longest path, often a star-like structure (a node with its neighbors). These islands are not very interesting for our purpose. We visually identified “interesting” islands and inspected them in detail. In the following list, we present basic information for each of selected island, i.e., the number of nodes for the selection of 20–200 nodes (and 20–100), the maximal SPC weight in the island and a short description of the island:

Island 1. , 0.297. Peer-review.

Island 2. , . Discovery of different isotopes.

Island 3. , . Biomass.

Island 7. , . Athletic trainers.

Island 8. , Sport refereeing and decision-making.

Island 9. , . Environment pollution.

Island 13. , . Toxicity testing.

Island 23. , . Peer-review in psychological sciences.

Island 24. , . Molecular interaction.

Only Island 1 and Island 23 dealt directly with the peer review. Other islands represented collateral stories. The Island 1 on peer-review was the most important because it had the maximal SPC weight at least 10.000 times higher than the next one, i.e., Island 8 on sport refereeing.

Fig. 12.

SPC islands [20,200]

For the sake of readability, we extracted from Island 1 a sub-island of size in range [20, 100], which is shown in Fig. 13. It contains the main path and strongly overlaps with the main paths in Fig. 8. The list of all publications from the main path (coded with 1), main paths (coded with 2) and SPC link island (20–100) (coded with 3) is shown in Table 6 in the “Appendix”. We found 105 works in the joint list. Only 9 publications were exclusively on main paths and only 10 publications were exclusively in the SPC link island. The three groups typology of works also held for the list of all 105 publications.

Fig. 13.

SPC link Island 1 [100]

Table 6.

List of works on main path (1), main paths (2) and island (3)—part 1

| Year | Code | First author | Title | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 123 | Meltzer, BN | The productivity of social scientists | AM J SOCIOL |

| 1954 | 123 | Dennis, W | Bibliographies of eminent scientists | SCIENTIFIC M |

| 1957 | 123 | Merton, RK | Priorities in scientific discovery—a chapter in the sociology of science | AM SOCIOL REV |

| 1958 | 123 | Polanyi, M | Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical philosophy | UP Chicago |

| 1965 | 123 | Crane, D | Scientists at major and minor universities | AM SOCIOL REV |

| 1966 | 123 | Bayer, AE | Some correlates of citation measure of productivity in science | SOCIOL EDUC |

| 1966 | 123 | Storer, NW | The social system of science | HRW |

| 1966 | 123 | Cartter, A | An Assessment of quality in graduate education | ACE |

| 1967 | 123 | Crane, D | Gatekeepers of science—some factors affecting selection of articles... | AM SOCIOL |

| 1967 | 123 | Cole, S | Scientific output and recognition—study in operation of reward system... | AM SOCIOL REV |

| 1971 | 123 | Zuckerma.H | Patterns of evaluation in science—...of referee system | MINERVA |

| 1972 | 23 | Garfield, E | Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation—journals can be ranked... | SCIENCE |

| 1974 | 123 | Ingelfin.FJ | Peer review in biomedical publication | AM J MED |

| 1978 | 23 | Wilson, JD | 70th annual-meeting of american-society-for-clinical-investigation,... | J CLIN INVEST |

| 1978 | 23 | Gottfredson, SD | Evaluating psychological-research reports—...of quality judgments | AM PSYCHOL |

| 1980 | 23 | Ruderfer, M | The fallacy of peer-review—judgment without science and a case-history | SPECULAT SCI TECHNOL |

| 1980 | 123 | Cicchetti, DV | Reliability of reviews for the american-psychologist... | AM PSYCHOL |

| 1982 | 123 | Peters, DP | Peer-review practices of psychological journals—the fate... | BEHAV BRAIN SCI |

| 1985 | 123 | Bailar, JC | Journal peer-review—the need for a research agenda | NEW ENGL J MED |

| 1985 | 23 | Moossy, J | Anonymous authors, anonymous referees—an editorial exploration | J NEUROPATH EXP NEUR |

| 1986 | 123 | Rennie, D | Guarding the guardians—a conference on editorial peer-review | JAMA |

| 1986 | 23 | Kochar, MS | The peer-review of manuscripts in need for improvement | J CHRON DIS |

| 1987 | 123 | Robin, ED | Peer-review in medical journals | CHEST |

| 1988 | 23 | Cleary, JD | Blind versus nonblind review—survey of selected medical journals | DRUG INTEL CLIN PHAR |

| 1990 | 123 | Mcnutt, RA | The effects of blinding on the quality of peer-review—a randomized trial | JAMA |

| 1990 | 23 | Rennie, D | Editorial peer-review in biomedical publication—the 1st-international-congress | JAMA |

| 1990 | 3 | Chalmers, I | A cohort study of summary reports of controlled trials | JAMA |

| 1991 | 23 | Cicchetti, DV | The reliability of peer-review for manuscript and grant submissions... | BEHAV BRAIN SCI |

| 1991 | 23 | Easterbrook, PJ | Publication bias in clinical research | LANCET |

| 1992 | 3 | Debellefeuille, C | The fate of abstracts submitted to a cancer meeting... | ANN ONCOL |

| 1992 | 123 | Rennie, D | Suspended judgment—editorial peer-review—let us put it on trial | CONTROL CLIN TRIALS |

| 1992 | 23 | Dickersin, K | Factors influencing publication of research results—follow-up of... | JAMA |

| 1993 | 123 | Rennie, D | More peering into editorial peer-review | JAMA |

| 1994 | 23 | Scherer, RW | Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts—a metaanalysis | JAMA |

| 1994 | 23 | Goodman, SN | Manuscript quality before and after peer-review and editing at Annals... | ANN INTERN MED |

Conclusions

This article provided a quantitative analysis of peer review as an emerging field of research by revealing patterns and connections between authors, fields and journals from 1950 to 2016. By collecting all available sources from WoS, we were capable of tracing the emergence and evolution of this field of research by identifying relevant authors, publications and journals, and revealing important development stages. By constructing several one-mode networks (i.e., co-authorship network, citation network) and two-mode networks, we found connections and collective patterns.

However, our work has certain limitations. First, given that data were extracted from WoS, works from disciplines and journals less covered by this tool could have been under-represented. This especially holds for humanities and social sciences, which are less comprehensively covered by WoS and more represented in Scopus and even more in GoogleScholar (e.g., Halevi et al. 2017), which also lists books and book chapters (e.g., Halevi et al. 2016). However, given that GoogleScholar does not permit large-scale data collection, a possible validation of our findings by using Scopus could be more feasible.

Furthermore, given that data were obtained using the queries “peer review*” and refereeing and that these terms could be used in many fields, e.g., sports, our dataset included some works that probably had little to do with peer review as a research field. For example, when reading the abstracts of certain works included in our dataset, we found works reporting ’Published by Elsevier Ltd. Selection and/or peer review under responsibility of’. An extra effort (unfortunately almost prohibitive) in cleaning the dataset manually would help filtering out irrelevant records. However, by using the main path and island methods, we successfully identified the most important and relevant publications on peer review without incurring in excessive cost of data cleaning or biasing our findings significantly.

Secondly, another limitation of our work is that we did not treat author name disambiguation, as evident in Table 3. This could be at least partially solved by developing automatic disambiguation procedures, although the right solution would be the adoption by WoS and publishers of the standards such as ResearcherID and ORCID to allow for a clear identification since from the beginning. To control for this, we could include in WoS2Pajek additional options to create short author names that will allow manual correction of names of critical authors.

With all these caveats, our study allowed us to circumscribe the field, capture its emergence and evolution and identify the most influential publications. Our main path procedures and islands method used SPC weights on citation arcs. It is important to note that the 47 publications from the main path were found in all other obtained lists of the most influential publications. They could be considered as the main corpus of knowledge for any newcomer in the field. More importantly, at least to have a dynamic picture of the field, we found these publications to be segmented in three phases defined by specific three time periods: before 1982, with works mostly published in social sciences journals (sociology, psychology and education); from 1983 to 2002, with works published almost exclusively in biomedical journals, mainly JAMA; and after 2003, with works published more preferably in science studies journals (e.g., Scientometrics, Research Evaluation, Journal of Informetrics).

This typology indicates the emergence and evolution of peer review as a research field. Initiatives to promote data sharing on peer review in scholarly journals and funding agencies (e.g., Casnici et al. 2017; Squazzoni et al. 2017) as well as the establishment of regular funding schemes to support research on peer review would help to strengthen the field and promote tighter connections between specialists.

Results also showed that while the term “peer review” itself was relatively unknown before 1970 (“referee” was more frequently used), publications on peer review significantly grew especially after 1990.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (Research Program P1-0294 and Research Projects J1-5433 and J5-5537) and was based upon work from COST Action TD1306 “New frontiers of peer review”—PEERE. Previous versions took advantages from comments and suggestions by many PEERE members, including Francisco Grimaldo, Daniel Torres-Salinas, Ana Marusic and Bahar Mehmani.

Appendix

The structure of names in constructed networks

The usual ISI name of a work as used in the CR field, e.g., ![]() has the following structure

has the following structure ![]() where AU is the first author’s name and SO[:20] is the string of the initial (up to) 20 characters in the SO field.

where AU is the first author’s name and SO[:20] is the string of the initial (up to) 20 characters in the SO field.

In WoS records, the same work can have different ISI names. To improve precision, the program WoS2Pajek supports also short names [similar to the names used in HISTCITE output (Garfield et al. 2003)]. They have the format: ![]()

For example: TREGENZA_T(2002)17:349. From the last names with prefixes VAN, DE, etc. the space is deleted. Unusual names start with a character * or $. The name [ANONYMOUS] is used for anonymous authors.

This construction of names of works provides a good balance between the synonymy problem (different names designating the same work) and the homonymy problem (a name designating different works). We treated the remaining synomyms and homonyms in the network data as a noise. If their effect surfaces into final results, we either corrected our copy of WoS data and repeated the analysis, or, if the correction required excessive work, simply reported the problem. A typical such case was the author name [ANONYMOUS] or combinations with some very frequent last names—in MathSciNet there are 85 mathematicians corresponding to the short name SMITH_R and 1792 mathematicians corresponding to the short name WANG_Y.

The composed keywords were decomposed in single words. For example, ‘peer review’ into ‘peer’ and ‘review’. On keywords obtained from titles of works we applied the lemmatization (using the Monty Lingua library).

The name ***** denoted a missing journal name.

Details about important works

In Tables 6, 7 and 8 a list of works on main path (1), main paths (2) and island (3) is presented. Only the first authors are listed.

Table 7.

List of works on main path (1), main paths (2) and island (3)—part 2

| Year | Code | First author | Title | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 23 | Fisher, M | The effects of blinding on acceptance of research papers by peer-review | JAMA |

| 1994 | 123 | Rennie, D | The 2nd international-congress on peer-review in biomedical publication | JAMA |

| 1994 | 123 | Smith, R | Promoting research into peer-review | BRIT MED J |

| 1995 | 123 | Jefferson, T | Are guidelines for peer-reviewing economic evaluations necessary... | HEALTH ECON |

| 1995 | 23 | Moher, D | Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials... | CONTROL CLIN TRIALS |

| 1996 | 23 | Jadad, AR | Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials... | CONTROL CLIN TRIALS |

| 1996 | 123 | Drummond, MF | Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ | BRIT MED J |

| 1996 | 23 | Begg, C | Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials—the CONSORT statement | JAMA |

| 1998 | 3 | Godlee, F | Effect on the quality of peer review of blinding reviewers and... | JAMA |

| 1998 | 3 | Justice, AC | Does masking author identity improve peer review quality?—a randomized controlled trial | JAMA |

| 1998 | 23 | Weber, EJ | Unpublished research from a medical specialty meeting—Why investigators fail to publish | JAMA |

| 1998 | 23 | van Rooyen, S | Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer review—A randomized trial | JAMA |

| 1998 | 23 | Black, N | What makes a good reviewer and a good review for a general medical journal? | JAMA |

| 1998 | 3 | Campanario, JM | Peer review for journals as it stands today—Part 1 | SCI COMMUN |

| 1998 | 123 | Jefferson, T | Evaluating the BMJ guidelines for economic submissions... | JAMA |

| 1998 | 3 | Howard, L | Peer review and editorial decision-making | BRIT J PSYCHIAT |

| 1998 | 123 | Rennie, D | Peer review in Prague | JAMA |

| 1998 | 2 | Hatch, CL | Perceived value of providing peer reviewers with abstracts and preprints... | JAMA |

| 1998 | 23 | Moher, D | Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy... | LANCET |

| 1998 | 23 | Callaham, ML | Positive-outcome bias and other limitations in the outcome of research abstracts... | JAMA |

| 1999 | 3 | van Rooyen, S | Effect of open peer review on quality of reviews and on reviewers’ recommendations... | BRIT MED J |

| 1999 | 123 | Smith, R | Opening up BMJ peer review—a beginning that should lead to complete transparency | BRIT MED J |

| 1999 | 123 | Goldbeck-Wood, S | Evidence on peer review—scientific quality control or smokescreen? | BRIT MED J |

| 1999 | 2 | Moher, D | Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: QUOROM | LANCET |

| 2000 | 123 | Walsh, E | Open peer review: a randomised controlled trial | BRIT J PSYCHIAT |

| 2000 | 2 | Stroup, DF | Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology—A proposal for reporting | JAMA |

| 2001 | 2 | Altman, DG | The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials... | ANN INTERN MED |

| 2001 | 2 | Moher, D | The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports... | LANCET |

| 2002 | 123 | Jefferson, T | Effects of editorial peer review—a systematic review | JAMA |

| 2002 | 123 | Jefferson, T | Measuring the quality of editorial peer review | JAMA |

| 2002 | 123 | Rennie, D | Fourth international congress on peer review in biomedical publication | JAMA |

| 2002 | 23 | Rowland, F | The peer-review process | LEARN PUBL |

| 2002 | 123 | Opthof, T | The significance of the peer review process against the background of bias... | CARDIOVASC RES |

| 2003 | 23 | Hojat, M | Impartial judgment by the “gatekeepers” of science:... | ADV HEALTH SCI EDUC |

| 2003 | 23 | Wets, K | Post-publication filtering and evaluation: Faculty of 1000 | LEARN PUBL |

Table 8.

List of works on main path (1), main paths (2) and island (3)—part 3

| Year | Code | First author | Title | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2 | Chan, AW | Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials... | JAMA |

| 2005 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Selection of research fellowship recipients by committee peer review... | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2005 | 123 | Daniel, HD | Publications as a measure of scientific advancement and of scientists’ productivity | LEARN PUBL |

| 2005 | 123 | Bornmann, L | Committee peer review at an international research foundation:... | RES EVALUAT |

| 2005 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Criteria used by a peer review committee for selection of research fellows... | INT J SELECT ASSESS |

| 2005 | 2 | Ioannidis, JPA | Why most published research findings are false | PLOS MED |

| 2006 | 123 | Bornmann, L | Selecting scientific excellence through committee peer review—a citation analysis... | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2006 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Potential sources of bias in research fellowship assessments:... | RES EVALUAT |

| 2007 | 123 | Bornmann, L | Convergent validation of peer review decisions using the h index... | J INFORMETR |

| 2007 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Gatekeepers of science—effects of external reviewers’ attributes... | J INFORMETR |

| 2007 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Row-column (RC) association model applied to grant peer review | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2008 | 23 | Marsh, HW | Improving the peer-review process for grant applications... | AM PSYCHOL |

| 2008 | 123 | Bornmann, L | Selecting manuscripts for a high-impact journal through peer review... | J AM SOC INF SCI TEC |

| 2008 | 23 | Bornmann, L | The effectiveness of the peer review process: inter-referee agreement... | ANGEW CHEM INT EDIT |

| 2008 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Latent Markov modeling applied to grant peer review | J INFORMETR |

| 2008 | 23 | Bornmann, L | Are there better indices for evaluation purposes than the h index?... | J AM SOC INF SCI TEC |

| 2009 | 123 | Bornmann, L | The luck of the referee draw: the effect of exchanging reviews | LEARN PUBL |

| 2009 | 2 | Opthof, T | The Hirsch-index: a simple, new tool for the assessment of scientific output... | NETH HEART J |

| 2009 | 2 | van der Heyden, MAG | Fraud and misconduct in science: the stem cell seduction | NETH HEART J |

| 2009 | 23 | Bornmann, L | The influence of the applicants’ gender on the modeling of a peer review... | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2010 | 23 | Bornmann, L | The manuscript reviewing process: Empirical research on review... | LIBR INFORM SCI RES |

| 2011 | 123 | Bornmann, L | Scientific Peer Review | ANNU REV INFORM SCI |

| 2011 | 123 | Bornmann, L | A multilevel modelling approach to investigating the...of editorial decisions:... | J R STAT SOC A STAT |

| 2011 | 3 | Franceschet, M | The first Italian research assessment exercise: A bibliometric perspective | J INFORMETR |

| 2011 | 23 | Waltman, L | On the correlation between bibliometric indicators and peer review:... | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2012 | 23 | Sen, CK | Rebound peer review: a viable recourse for aggrieved authors? | ANTIOXID REDOX SIGN |

| 2013 | 123 | Lee, CJ | Bias in peer review | J AM SOC INF SCI TEC |

| 2014 | 3 | Bornmann, L | Do we still need peer review? an argument for change | J ASSOC INF SCI TECH |

| 2015 | 3 | Siler, K | Measuring the effectiveness of scientific gatekeeping | P NATL ACAD SCI USA |

| 2015 | 123 | Garcia, JA | The principal-agent problem in peer review | J ASSOC INF SCI TECH |

| 2015 | 123 | Garcia, JA | Adverse selection of reviewers | J ASSOC INF SCI TECH |

| 2015 | 123 | Moustafa, K | Don’t infer anything from unavailable data | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2015 | 123 | Garcia, JA | Bias and effort in peer review | J ASSOC INF SCI TECH |

| 2015 | 123 | Garcia, JA | The author–editor game | SCIENTOMETRICS |

| 2016 | 123 | Rodriguez-Sanchez, R | Evolutionary games between authors and their editors | APPL MATH COMPUT |

Contributor Information

Vladimir Batagelj, Email: vladimir.batagelj@fmf.uni-lj.si.

Anuška Ferligoj, Email: anuska.ferligoj@fdv.uni-lj.si.

Flaminio Squazzoni, Email: flaminio.squazzoni@unibs.it.

References

- Batagelj, V. (2003) Efficient algorithms for citation network analysis. http://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0309023.

- Batagelj, V. (2007). WoS2Pajek. Manual for version 1.4, July 2016. http://vladowiki.fmf.uni-lj.si/doku.php?id=pajek:wos2pajek.

- Batagelj V, Cerinšek M. On bibliographic networks. Scientometrics. 2013;96(3):845–864. doi: 10.1007/s11192-012-0940-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batagelj, V., Doreian, P., Ferligoj, A., & Kejžar, N. (2014). Understanding large temporal networks and spatial networks: Exploration, pattern searching, visualization and network evolution. London: Wiley series in computational and quantitative social science, Wiley.

- Bornmann L. Scientific peer review. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology. 2011;45(1):197–245. doi: 10.1002/aris.2011.1440450112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casnici, N., Grimaldo, F., Gilbert, N., & Squazzoni, F. (2017). Attitudes of referees in a multidisciplinary journal: An empirical analysis. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology,68(7), 1763–1771.

- Cole S, Cole JR. Visibility and the structural bases of awareness of scientific research. American Sociological Review. 1973;33:397–413. doi: 10.2307/2091914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nooy W, Mrvar A, Batagelj V. Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek. Structural analysis in the social sciences. Revised and Expanded Second. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MA, Roy S. Academic research in the 21st century: Maintaining scientific integrity in a climate of perverse incentives and hypercompetition. Environmental Engineering Science. 2016;34(1):51–61. doi: 10.1089/ees.2016.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe, A., Coate, K., Curry, S., Lawson, S., Moxham, N., & Røstvik, C. M. (2017). Untangling academic publishing: A history of the relationship between commercial interests, academic prestige and the circulation of research. Zenodo project. doi:10.5281/zenodo.546100.

- Garfield E., Pudovkin, A. I., Istomin, V. S., Histcomp—(compiled Historiography program). http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/histcomp/guide.html.

- Garfield E, Pudovkin AI, Istomin VS. Why do we need algorithmic historiography? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2003;54(5):400–412. doi: 10.1002/asi.10226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauffriau M, Larsen PO, Maye I, Roulin-Perriard A, von Ins M. Publication, cooperation and productivity measures in scientific research. Scientometrics. 2007;73(2):175–214. doi: 10.1007/s11192-007-1800-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C. Scientific misconduct. Annual Review of Psychology. 2016;67(1):693–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi G, Moed H, Bar-Ilan J. Suitability of Google Scholar as a source of scientific information and as a source of data for scientific evaluation—Review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics. 2017;11(3):823–834. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2017.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi G, Nicolas B, Bar-Ilan J. The complexity of measuring the impact of books. Publishing Research Quarterly. 2016;32(3):187–200. doi: 10.1007/s12109-016-9464-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hummon NP, Doreian P. Connectivity in a citation network: The development of DNA theory. Social Networks. 1989;11:39–63. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(89)90017-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leydesdorff L, Ahrweiler P. In search of a network theory of innovations: Relations, positions, and perspectives. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2014;65(11):2359–2374. doi: 10.1002/asi.23127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JS, Lu LYY. An integrated approach for main path analysis: Development of the Hirsch index as an example. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2012;63:528–542. doi: 10.1002/asi.21692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Squazzoni F, Bravo G, Takács K. Does incentive provision increase the quality of peer review? An experimental study. Research Policy. 2013;42(1):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Squazzoni, F., Grimaldo, F., & Marušić, A. (2017). Publishing: Journals could share peer-review data. Nature, 546(7658), 352–352. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Squazzoni, F., & Takács, K. (2011). Social simulation that ‘peers into peer review’. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 14(4), 3.

- van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84(2):523–538. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eck NJ, Waltman L. CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. Journal of Informetrics. 2014;8(4):802–823. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. Chinese surname. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_surname.

- Wikipedia. Histcite. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histcite.

- Wikipedia. Peer review. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer_review.

- Zaveršnik, M., & Batagelj, V. (2004) Islands. XXIV. International sunbelt social network conference. Portorož, May 12–16. http://vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si/pub/networks/doc/sunbelt/islands.pdf.