Relationships between individuals are important to estimate genetic variances within a population and covariances between populations. Here, Wientjes.....

Keywords: genetic correlation between populations, genomic relationships, genetic variance, multi-trait model, Genomic Selection, Shared Data Resources, GenPred

Abstract

Different methods are available to calculate multi-population genomic relationship matrices. Since those matrices differ in base population, it is anticipated that the method used to calculate genomic relationships affects the estimate of genetic variances, covariances, and correlations. The aim of this article is to define the multi-population genomic relationship matrix to estimate current genetic variances within and genetic correlations between populations. The genomic relationship matrix containing two populations consists of four blocks, one block for population 1, one block for population 2, and two blocks for relationships between the populations. It is known, based on literature, that by using current allele frequencies to calculate genomic relationships within a population, current genetic variances are estimated. In this article, we theoretically derived the properties of the genomic relationship matrix to estimate genetic correlations between populations and validated it using simulations. When the scaling factor of across-population genomic relationships is equal to the product of the square roots of the scaling factors for within-population genomic relationships, the genetic correlation is estimated unbiasedly even though estimated genetic variances do not necessarily refer to the current population. When this property is not met, the correlation based on estimated variances should be multiplied by a correction factor based on the scaling factors. In this study, we present a genomic relationship matrix which directly estimates current genetic variances as well as genetic correlations between populations.

WHEN estimating the additive genetic values of individuals, relationships between individuals are used to describe the covariances between additive genetic values. Those relationships are expressed relative to a base population, consisting of, on average, unrelated individuals that have average self-relationships of one, for which the additive genetic variance is estimated. The method used to calculate the relationships affects the used base population and, therefore, the estimated additive genetic variance as well (Speed and Balding 2015; Legarra 2016). By using current allele frequencies to calculate a genomic relationship matrix, the current population is the base population for which additive genetic variances are estimated (Hayes et al. 2009).

Genomic data enable the calculation of relationships between distantly related individuals, for example between individuals from different populations. Those relationships can be used to estimate genetic correlations between populations using a multi-trait model (Karoui et al. 2012), where the same trait in each population is modeled as a different trait. Due to differences in allele frequencies and environments, in combination with nonadditive effects and genotype-by-environment interactions, allele substitution effects of causal loci can differ between populations (e.g., Fisher 1918, 1930; Falconer 1952). Moreover, some causal loci might segregate in only one population. Therefore, genetic correlations between populations can differ from one.

The genetic correlation between populations is an important parameter since it is used to understand the genetic architecture and evolution of complex traits, such as disease traits in humans (De Candia et al. 2013; Brown et al. 2016). In genomic prediction, combining populations in one training population is important for applications in animals (e.g., Karoui et al. 2012; Olson et al. 2012), plants (e.g., Lehermeier et al. 2015), and humans (e.g., De Candia et al. 2013). Although the genetic correlation between those populations is not needed as an explicit parameter for implementing multi-population genomic prediction, its value does determine the benefit of combining those populations in one training population (Wientjes et al. 2016).

Different methods are available to calculate multi-population genomic relationship matrices (Harris and Johnson 2010; Erbe et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2013; Makgahlela et al. 2013). The two most important differences between the methods are: (1) the assumed relation between effect size and allele frequency of loci, namely assuming that across-loci effect size and allele frequency are independent (e.g., method 1 of VanRaden 2008) or assuming that loci with a lower allele frequency have a larger effect (e.g., method 2 of VanRaden 2008 and Yang et al. 2010); and (2) the used allele frequency, namely allele frequencies specific to each population, the average allele frequency across the populations, or the estimated allele frequency when the populations separated. The method used to calculate the genomic relationships is likely to affect the genetic correlation estimate between populations, but the required properties for unbiasedly estimating this genetic correlation are not yet known.

The aim of this article is to define the multi-population genomic relationship matrix to directly estimate current genetic variances within and genetic correlations between populations. We theoretically derived this relationship matrix and validated it using simulations. Since the true relationships between individuals for a certain trait are defined at the causal loci and the aim of this article is to define the theoretically appropriate genomic relationship matrix, we present a relationship matrix based on genotypes at causal loci.

Materials and Methods

Theory

The additive genetic correlation, rg, is the correlation between additive genetic values (A) for two traits of the same individual (Bohren et al. 1966; Falconer and Mackay 1996). In an additive model, rg can be shown to be equal to the average correlation between allele substitution effects at causal loci of two traits (), denoted as trait 1 and 2, under the following assumptions: (1) the correlation originates from pleiotropy; (2) genetic values are independent between loci (i.e., the effect at one locus for a certain trait is not a predictor of the effect at another locus for the same trait. Note that this does not require linkage equilibrium (LE) between causal loci, but an equal probability for a positive allele at one locus to be linked to either a positive or a negative allele at the other locus); and (3) across loci, allele substitution effects and allele frequency are independent from each other (i.e., the allele substitution effect at a locus does not depend on the allele frequency at that locus). This equality can be shown for individual i by considering both genotypes (z) and allele substitution effects (α) at all nc causal loci as random:

| (1) |

where j and l denote different causal loci, and are variances of allele substitution effects across causal loci within population 1 and 2, and is the covariance between allele substitution effects of population 1 and 2 across causal loci. Genotypes are represented by allele counts coded as 0, 1, and 2 that are centered by subtracting 2p, where p is the allele frequency for the counted allele.

Similar to genetic correlations between traits in one population, the genetic correlation (rg) between populations can be estimated in a multi-trait model using a relationship matrix and REML by modeling the phenotypes of two populations as different traits (Karoui et al. 2012). This approach is known as multi-trait GREML. In the following, we refer to trait 1 as the trait expressed in population 1, and to trait 2 as the trait expressed in population 2. When considering performance in different populations as different traits, individuals have a phenotype for only one trait. Therefore, the (co)variance structure of the additive genetic values can be written as (Visscher et al. 2014)

| (2) |

where a1 is the vector with additive genetic values for individuals from population 1 for trait 1, a2 is the analogous vector for individuals from population 2 for trait 2, and are genetic variances for trait 1 and 2, is the genetic covariance between the traits, G11 is a matrix with genomic relationships in population 1, G22 is a matrix with genomic relationships in population 2, and G12 and G21(=) are matrices with genomic relationships between population 1 and 2.

To derive the definition of the genomic relationships in Equation 2, we derive the variances and covariance of the additive genetic values for the two traits. Naturally, this will result in an equation to calculate the genomic relationship matrix (G) using multiple populations to estimate (co)variances in the current populations.

When both populations are in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, allele substitution effects are independent from allele frequency across loci, and, within a trait, genetic values at causal loci are independent from each other; the genetic variance for trait 1 is , where p1j is the allele frequency at locus j in population 1 (Falconer and Mackay 1996). Hence, the variance of a1 is:

| (3) |

where Z1 is a n1 × nc matrix of centered genotypes for all individuals from population 1 (n1) for all causal loci, and α1 is a vector of length nc with allele substitution effects at causal loci for trait 1.

Similarly,

| (4) |

The genetic covariance between two traits is:

| (5) |

Therefore, the covariance between the genetic values of population 1 and 2 is:

| (6) |

From Equations 3, 4, and 6, it follows that the genomic relationship matrix (G) is:

| (7) |

When allele frequencies from the current population are used, G from Equation 7 estimates current genetic (co)variances. Lourenco et al. (2016) presented a comparable G matrix for combining purebred and crossbred animals. Note that the covariance of the genotypes between the populations, , is divided by the SDs of the genotypes in each population, and . Therefore, the relationships in this G are defined as correlations between the genotypes of the individuals.

In Equation 7, G uses three different scaling factors for the different blocks, , , and . Note that , but since this is not a general property of genomic relationship matrices, we separately defined . Hence, the variance–covariance matrix in Equation 2 becomes:

| (8) |

Equation 8 shows that the scaling factors in G and the (co)variances are completely confounded. Therefore, when using other scaling factors in G for which k12 is not necessarily equal to , the genetic correlation can be estimated as

| (9) |

Equation 9 shows that the genetic correlation is directly estimated from the estimated variances when the scaling factors of G fulfill the property . When , the correlation based on estimated variances should be multiplied by to correct the estimate. By changing the scaling factors, the estimated genetic variances change as well. When genetic variances of the current population are of interest, the within-population blocks in G should be scaled as in Equation 7 and allele frequencies from the current population should be used (Hayes et al. 2009; Legarra 2016), or the estimated variance component should be multiplied by for population 1 or by for population 2.

Equation 8 and Equation 9 show that the genetic correlation is estimated when the scaling factors in G are the same for all blocks. When all scaling factors are equal to 1, so effectively no scaling factor is used, the (co)variances represent the (co)variances of the allele substitution effects across causal loci, i.e., , , and . A disadvantage of this scaling is that elements of G can become very large, which can result in very small estimated variances that may be flagged as too small in statistical software. This might be prevented by either scaling up the phenotypic variance by multiplying all phenotypes by a constant, or by scaling down the elements in G by dividing all elements by the same constant. Both scaling approaches have no influence on the genetic correlation, but do affect the estimated genetic (co)variances.

Simulations

Simulations were used to validate G (Equation 7). Two scenarios were simulated, with causal loci either in LE or in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with each other. Note that in both scenarios, no selection was present and genetic values were independent between causal loci.

For both scenarios, two populations (2500 individuals each) with phenotypes for a trait influenced by the same 15,000 loci were simulated. For the first scenario, with causal loci in LE, allele frequencies of loci were randomly sampled from a U-shape distribution, independently in both populations. Thereafter, genotypes were allocated to individuals according to the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, assuming that loci were segregating independently.

For the second scenario, with causal loci in LD, a population structure was simulated in QMSim software (Sargolzaei and Schenkel 2009). An historical population was simulated for 1000 generations. Population size was 2000 (1000 males, 1000 females) in generation 1 and this was gradually reduced to 100 individuals in generation 500, after which it increased again to 2000 individuals in generation 1000. This bottleneck was simulated to generate LD. The simulated genome consisted of 30 chromosomes of 100 cM each, with 100,000 randomly positioned dimorphic loci per chromosome; a recurrent mutation rate of 0.00005; and on average one recombination per chromosome. After 1000 generations, the historical population was split in two populations with 250 males and 500 females, and a litter size of 5. At this split, 60,000 loci with a minor allele frequency of at least 0.05 were selected and the mutation rate was set to zero. After another 500 nonoverlapping generations with random mating, 15,000 loci segregating in both populations were randomly selected to become causal loci. Allele frequencies of causal loci followed a uniform distribution, and neighboring causal loci were on average 0.2 cM apart with an average r2 value of 0.25.

For both scenarios, allele substitution effects were sampled from a bivariate normal distribution with mean zero and variance 1, and a correlation of 0.5 between allele substitution effects in both populations. Allele substitution effects were multiplied by the corresponding genotypes to calculate additive genetic values for individuals, assuming additive gene action. Environmental effects were sampled from a normal distribution with variance (−1) times the genetic variance, where the genetic variance was calculated across all individuals in both populations. Heritability was set to 0.9, to ensure that there was sufficient power to estimate (co)variances. Phenotypes were the sum of additive genetic and environmental effects, and were standardized to an average of 0 and SD of 100. Simulations were replicated 100 times.

Phenotypes were analyzed using the following bivariate model:

where y1 and y2 are vectors with phenotypes for population 1 and 2, x1 and x2 are incidence vectors relating phenotypes to the mean in population 1 (μ1) or population 2 (μ2), Z1 and Z2 are incidence matrices relating phenotypes to estimated additive genetic values for performance in population 1 (a1) or population 2 (a2), and e1 and e2 are vectors containing residual effects. Estimated additive genetic values were assumed to follow a normal distribution (∼N, Equation 2), and residuals were assumed to be independent (∼N, where and are the residual variances in population 1 and 2). All analyses were performed in ASReml (Gilmour et al. 2015) using a REML approach, which is known to result in unbiased variance estimates (Henderson 1984).

Four G matrices were used: two G matrices derived above, and two commonly used G matrices for multiple populations (Chen et al. 2013; Makgahlela et al. 2013). The methods differed in scaling factors as well as in centering of genotypes, being performed either within or across populations. For all four methods, G was based on genotypes at causal loci and G was bent when singularities appeared by replacing eigenvalues below 10−6 with 10−6 (Jorjani et al. 2003).

The first three methods centered genotypes in Z within population as , where gijm is the allele count of individual i from population m at locus j, and pjm is the allele frequency in population m at locus j. The first method, G_New, scaled G following Equation 7:

In the second method, G_1, scaling factors were equal to 1:

The third method, G_Chen, calculated G according to Chen et al. (2013):

The fourth method, G_Across, centered genotypes using the average allele frequency across populations instead of population-specific allele frequencies (e.g., Makgahlela et al. 2013). Thus, the matrix of genotypes, denoted Z*, had elements , where is the average allele frequency across populations at locus j. The scaling factor was the same for all blocks:

G_New, G_1, and G_Across fulfilled the property to directly estimate the genetic correlation. In G_Chen, when allele frequencies in the two populations were different. Therefore, the correlation estimated with G_Chen was multiplied by to correct the estimate. Moreover, the current populations were the base population for within-population blocks of G_New and G_Chen, so genetic variances in the current populations were estimated (Speed and Balding 2015; Legarra 2016). As explained before, estimated variances of G_1 represented the variances of allele substitution effects across causal loci. For G_Across, the base population was not clearly defined, so the interpretation of the estimated variances is unclear.

Data availability

Supplemental Material, File S1, contains the R-script and seeds to simulate genotypes and phenotypes and to calculate G matrices for the scenario with causal loci in LE. File S2 contains the QMSim input file, R-script, and seeds to simulate genotypes and phenotypes and to calculate G matrices for the scenario with causal loci in LD.

Results

Genetic variances

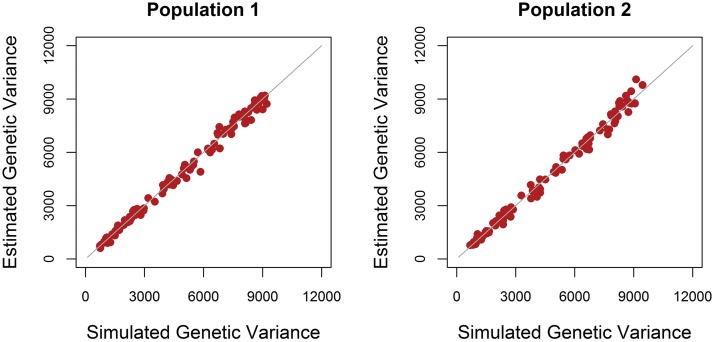

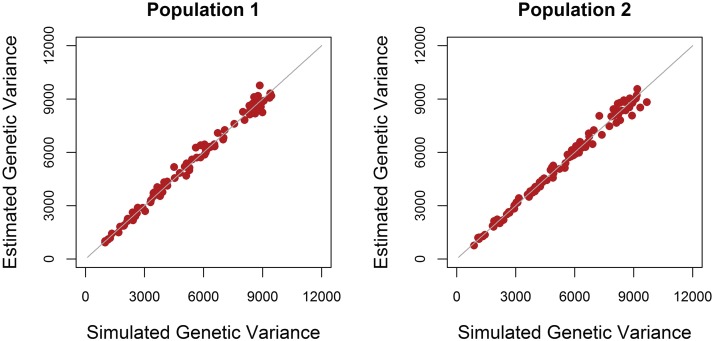

Estimated genetic variances using G_New varied only slightly around the simulated values, both when causal loci were in LE or in LD (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This shows that G_New unbiasedly estimated genetic variances in the current populations for both scenarios.

Figure 1.

Estimated vs. simulated genetic variances when causal loci were in LE. The estimated genetic variance in both populations in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New) vs. the simulated genetic variance. The gray line represents the line y = x.

Figure 2.

Estimated vs. simulated genetic variances when causal loci were in LD. The estimated genetic variance in both populations in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New) vs. the simulated genetic variance. The gray line represents the line y = x.

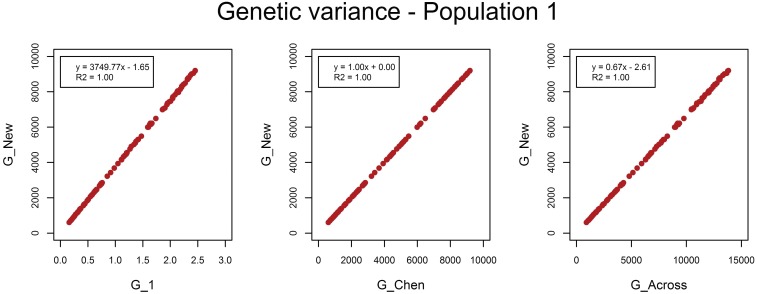

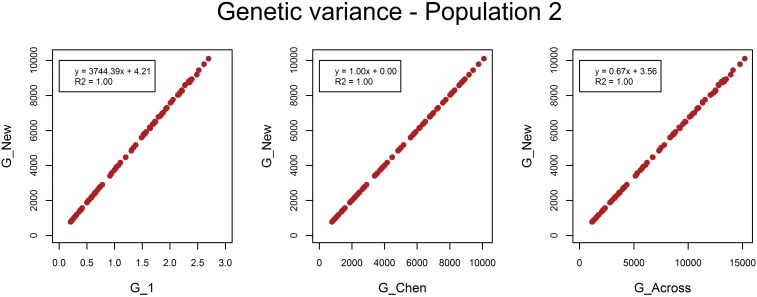

As expected, G_New and G_Chen estimated the same genetic variances (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The estimated variances of G_1 represent the variances of allele substitution effects across causal loci, i.e., and . By multiplying those variances by for population m, genetic variances identical to G_New and G_Chen were obtained. When causal loci were in LE, genetic variances estimated with G_Across were higher than genetic variances estimated with G_New and G_Chen by a factor of ∼1.5. The scaling factors k1 and k2 were higher by a factor of ∼1.5. Hence, when multiplying estimated variances of G_Across by the ratio in scaling factors, variances became identical to those with G_New and G_Chen. The same applied for the estimated genetic variances with causal loci in LD, where the factor was 1.15. So, the difference in estimated variances between methods to calculate G was completely explained by the difference in scaling factors, while centering genotypes within or across populations had no effect on estimated variances. Estimated residual variances were exactly the same for the four G matrices.

Figure 3.

Estimated genetic variances in population 1 when causal loci were in LE. The estimated genetic variance in population 1 in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New) vs. the estimated genetic variance using population-specific allele frequencies and either a genomic relationship matrix with scaling factors set to 1 (G_1), or based on the method of Chen et al. (2013) (G_Chen), or using allele frequencies across populations (G_Across).

Figure 4.

Estimated genetic variances in population 2 when causal loci were in LE. The estimated genetic variance in population 2 in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New) vs. the estimated genetic variance using population-specific allele frequencies and either a genomic relationship matrix with scaling factors set to 1 (G_1), or based on the method of Chen et al. (2013) (G_Chen), or using allele frequencies across populations (G_Across).

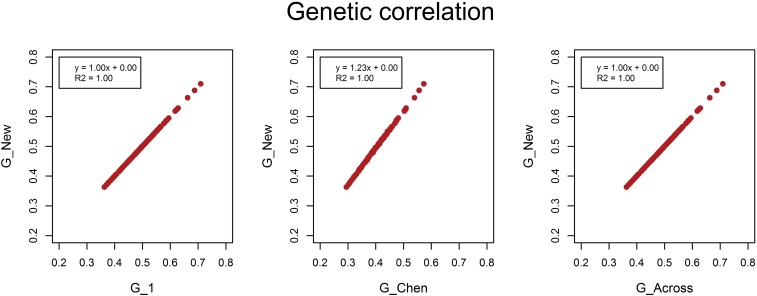

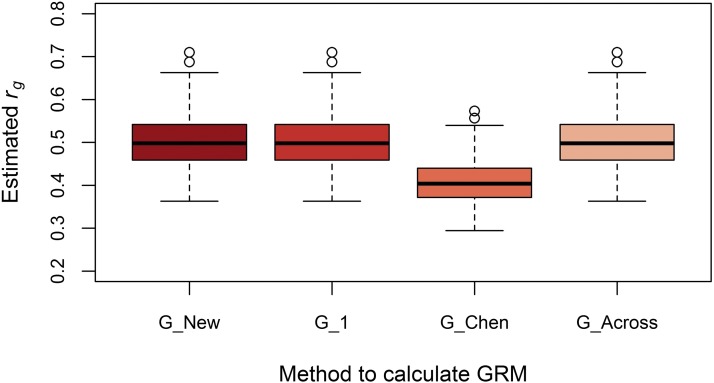

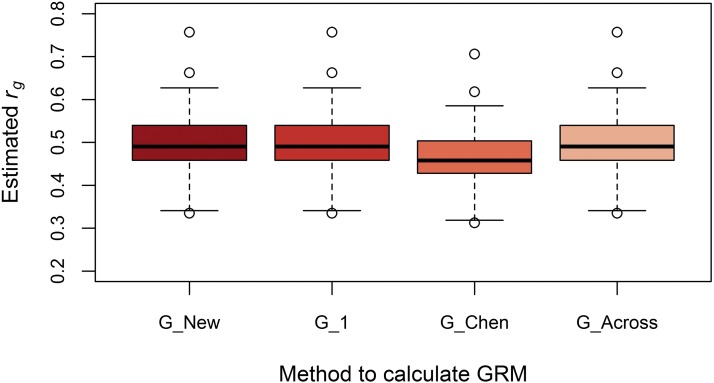

Genetic correlation

Despite differences in (co)variance estimates, G_New, G_1, and G_Across yielded the same average estimated genetic correlation (Figure 5), which was an unbiased estimate of the simulated genetic correlation (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This is because differences in genetic covariances among models were compensated by corresponding differences in genetic variances. When causal loci were in LE, the estimated genetic correlation using G_Chen was ∼20% lower. When multiplying this estimate by ≈ 1.23, the genetic correlation became identical to the other three methods. When causal loci were in LD, the estimated genetic correlation using G_Chen was ∼7% lower, which was in agreement with ≈ 1.07.

Figure 5.

Estimated genetic correlations between population 1 and 2 when causal loci were in LE. The estimated genetic correlation between population 1 and 2 in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New) vs. the estimated genetic correlation using population-specific allele frequencies and either a genomic relationship matrix with scaling factors set to 1 (G_1), based on the method of Chen et al. (2013) (G_Chen), or using allele frequencies across populations (G_Across).

Figure 6.

Boxplot of estimated genetic correlations using four methods to calculate genomic relationships with causal loci in LE. The estimated genetic correlation between population 1 and 2 in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New), using population-specific allele frequencies and either a genomic relationship matrix with scaling factors set to 1 (G_1), or based on the method of Chen et al. (2013) (G_Chen), or using allele frequencies across populations (G_Across). The simulated genetic correlation was 0.5.

Figure 7.

Boxplot of estimated genetic correlations using four methods to calculate genomic relationships with causal loci in LD. The estimated genetic correlation between population 1 and 2 in each of the 100 replicates using the genomic relationship matrix derived in this study (G_New), using population-specific allele frequencies and either a genomic relationship matrix with scaling factors set to 1 (G_1), or based on the method of Chen et al. (2013) (G_Chen), or using allele frequencies across populations (G_Across). The simulated genetic correlation was 0.5.

Discussion

The aim of this article was to define the multi-population genomic relationship matrix to estimate current genetic variances within and genetic correlations between populations. Our derived genomic relationship matrix, G_New, yields unbiased estimates of current genetic variances, covariances, and correlations, both when causal loci are in LE or LD with each other. Moreover, we showed the required property for other genomic relationship matrices to estimate genetic correlations between populations, even though estimated genetic variances are not necessarily related to the current populations.

Methods to calculate the genomic relationship matrix

Since G_New unbiasedly estimated both current genetic variances within as well as genetic correlations between populations, we conclude that G_New correctly defines the relationships at causal loci within as well as between populations. G_Chen also estimated current genetic variances, but estimated genetic correlations had to be multiplied by . G_1 estimated the correct genetic correlation, but estimated the variance of allele substitution effects across causal loci instead of the genetic variance. Although the base population in G_Across was not well defined, genetic correlations were correctly estimated, but there was no clear interpretation of estimated genetic variances. Results also showed that genetic (co)variances were not affected by centering the allele counts, as shown before by Strandén and Christensen (2011).

Table 1 gives an overview of the most frequently used methods to calculate G using multiple populations, with scaling factors and correction factors for the estimated genetic correlation. G_New, G_1, G_Across, and the method described by Erbe et al. (2012) directly estimate the correct genetic correlation. G_Chen does not directly estimate the genetic correlation, but the estimate can be corrected using the scaling factors. Those five methods assume that allele substitution effects are independent from allele frequency across loci, similar to method 1 of VanRaden (2008). This is in contrast to another regularly used method, namely method 2 of VanRaden (2008), also described by Yang et al. (2010). This method yields a valid definition of relationships between individuals only when the average effect at a locus is proportional to the reciprocal of the square root of expected heterozygosity at that locus (Appendix, Equation A8). So this method assumes that, across loci, allele substitution effects are fully dependent on their allele frequency, with larger effects for rarer alleles. For traits determined by relatively few genes and undergoing directional selection, this assumption may be plausible, since selection acts more strongly on causal loci with larger effects (Haldane 1924; Wright 1931, 1937). It is, however, a very strong assumption in general. Many traits may experience only weak selection, and/or are determined by many genes. In those cases, the allele frequency distribution is determined mainly by the interplay of mutation and drift, and a direct relationship between effect size and allele frequency is not expected. Therefore, the assumption that across loci allele substitution effects and allele frequency are independent seems more realistic for most traits. Moreover, when across loci allele substitution effects depend on allele frequency, effects for exactly the same trait would differ between populations when allele frequencies differ. This makes the interpretation of estimated genetic correlations between populations using method 2 of VanRaden (2008) rather difficult. For those reasons, we advise the use of G matrices based on method 1 instead of method 2 of VanRaden (2008), especially when multiple populations are considered.

Table 1. Overview of frequently used method to calculate G across populations with scaling and correction factors.

| Method of calculating Ga | Described by | Used scaling factors of the different blocks in Gb | Correction factor to correct the genetic correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1c | k2c | k12c | |||

| G_New | This study | Not needed | |||

| G_1 | This study | 1 | 1 | 1 | Not needed |

| G_Chen | Chen et al. (2013) | ||||

| G_Across | VanRaden (2008), Makgahlela et al. (2013) | Not needed | |||

| Erbe | Erbe et al. (2012) | Not needed | |||

| VanRaden method 2/Yang | VanRaden (2008), Yang et al. (2010) | No. of locid | No. of locid | No. of locid | Unknown |

Methods were compared assuming that no adjustment for inbreeding or regression toward the pedigree relationship matrix was performed.

k1 is the scaling factor of the block containing relationships in population 1, k2 is the scaling factor of the block containing relationships in population 2, and k12 is the scaling factor of the block containing relationships between population 1 and 2.

is the allele frequency in population 1, is the allele frequency in population 2, is the average allele frequency across populations, and is the estimated allele frequency when the populations separated.

Per locus i, genotypes are scaled by

For a specific trait, relationships between individuals are defined by the relationships at causal loci for that trait. Because LD between causal loci surfaces in the genomic relationships, LD between causal loci does not create bias in estimated genetic (co)variances and correlations. Since causal loci are generally unknown, genomic marker data are used to estimate genomic relationships. By using markers, differences in LD between markers and causal loci can reduce the estimated genetic correlation (Gianola et al. 2015). This may be especially important for estimating genetic correlations between populations, since the strength and phase of LD differs across populations in humans (Sawyer et al. 2005), livestock (e.g., Heifetz et al. 2005; Gautier et al. 2007; Veroneze et al. 2013), and plants (Flint-Garcia et al. 2003; Lehermeier et al. 2014). Moreover, markers might not explain all genetic variance (e.g., Yang et al. 2010; Daetwyler et al. 2013), which can affect the estimated genetic correlation when the genetic effects captured by markers have a higher or lower genetic correlation than the part not captured (Bulik-Sullivan et al. 2015). Here, the focus was to theoretically define the multi-population genomic relationship matrix. Since the true relationships between individuals for a certain trait are defined at the causal loci, we used genotypes of causal loci to define G. A clear definition of the genomic relationships is the essential starting point for estimating genomic relationships using marker information.

Other approaches to estimate genetic correlations between populations

We focused on using genomic relationships in a multi-trait model to estimate genetic correlations between populations. Genetic correlations can also be estimated using summary statistics of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (Bulik-Sullivan et al. 2015; Brown et al. 2016) or using random regression on genotypes (Sørensen et al. 2012; Krag et al. 2013). The method based on summary statistics of GWAS combines information from multiple studies and weights estimated marker effects by LD overlap and corresponding z score (Bulik-Sullivan et al. 2015; Brown et al. 2016). This method is beneficial when collecting enough data is expensive and data sharing is not possible. It is, however, not known whether this method estimates the correct genetic correlation. The method using random regression on genotypes is equivalent to the multi-trait GREML method used in this study, since both estimate the same additive genetic values when genotypes are centered and scaled in the same way (Habier et al. 2007; VanRaden 2008; Goddard 2009). Variances estimated with random regression on centered genotypes represent variances of allele substitution effects across loci (Meuwissen et al. 2001), similar to G_1. Hence, random regression on centered genotypes can also be used to estimate genetic correlations between populations. When genotypes for random regression are centered and scaled, estimated genetic correlations become equal to the estimates using G based on method 2 of VanRaden (VanRaden 2008; Yang et al. 2010). Therefore, the interpretation of this estimated genetic correlation remains unclear as well.

Importance of the genetic correlation between populations

Populations differ in both genetic and environmental factors, which can result in considerable differences in the expression of complex traits across populations. The genetic correlation between populations provides insight into the differences in genetic architecture of traits across populations (Brown et al. 2016). A low genetic correlation between populations indicates that causal loci have different effects and/or that different causal loci are underlying the trait. This information has important implications for transferring the results of biomedical studies or GWAS from one population to another. Moreover, the genetic correlation provides insight into the potential to use information across populations for genomic prediction. When the genetic correlation is low, the accuracy of estimated genetic values is unlikely to increase by combining populations in one training population or by using information about the location of casual variants across populations, as is done in multi-task Bayesian models (Chen et al. 2014; Technow and Totir 2015), since effects and locations of causal loci are likely to be different.

Another factor affecting the benefit of sharing information across populations is the relatedness between the populations, which is expected to be at least partly related to the genetic correlation between populations. More distantly related populations generally have more different allele frequencies due to an accumulation of the effects of selection and genetic drift over generations (e.g., Falconer and Mackay 1996). In combination with nonadditive effects (Fisher 1918, 1930), those differences in allele frequencies reduce the genetic correlation. The genetic correlation, however, differs across traits (e.g., Karoui et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2014; Brown et al. 2016) and is also affected by differences in the environments of the populations (Falconer 1952). This shows the importance of investigating the genetic correlation for the trait of interest as well as the relatedness between the populations when deciding to use information across populations.

For implementing multi-population genomic prediction, explicit and accurate knowledge of genetic (co)variances and correlations is not required. Therefore, accuracy of estimated genetic values is quite consistent across methods for calculating G (Makgahlela et al. 2013, 2014; Lourenco et al. 2016). For predicting the accuracy in those scenarios, however, an accurate estimation of genetic correlations is essential (Wientjes et al. 2015, 2016). Generally, combining populations is beneficial when the training population for one of the populations is small and the genetic relatedness and correlation between the populations high, which is for example the case between subpopulations from the same breed kept in different environments.

Conclusions

The properties of genomic relationships affect estimates of genetic variances within as well as genetic correlations between populations. For estimating current genetic variances, allele frequencies of the current population should be used to calculate relationships within that population. For estimating genetic correlations between populations, scaling factors of the different blocks of the relationship matrix, based on method 1 of VanRaden (2008), should fulfill the property . When this property is not fulfilled, estimated genetic correlations can be corrected by multiplying the estimate by . In this study we present a genomic relationship matrix, G_New, which directly results in current genetic variances as well as genetic correlations between populations.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.117.300152/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) and the Breed4Food consortium partners Cobb Europe, CRV, Hendrix Genetics, and Topigs Norsvin.

Appendix

The G matrix based on method 2 of VanRaden (2008) and Yang et al. (2010), G_VR2, weights loci by the reciprocal of the square root of the variance of its genotypes. In this Appendix, it is shown that this is only correct under the assumption that the variance of the average effect (α) at a locus, say l, is inversely proportional to expected heterozygosity at that locus,

| (A1) |

where c is a constant and is the allele frequency at locus l.

Consider the single-trait mixed model , where a is the vector of random additive genetic effects, with . This mixed model is valid only when indeed represents the covariances between additive genetic effects (A) of individuals. This requires that

| (A2) |

where i and j are individuals.

By definition, the additive genetic effect of an individual is the sum of the average effects at its loci, weighted by the centered allele count (Fisher 1918; Falconer and Mackay 1996),

| (A3) |

where is the allele count of individual i at locus l, taking values 0, 1, or 2. Thus,

| (A4) |

For the genetic covariance, the terms are independent between loci by definition when there is no selection (Bulmer 1971), so that the covariance reduces to

| (A5) |

Substituting the relationship between average effects and allele frequency given by Equation A1 yields

| (A6) |

Analogously, the genetic variance equals

where is the number of loci. Finally, from Equation A2,

| (A7) |

which is G_VR2. Thus obtaining G_VR2 requires Equation A1.

Hence, G_VR2 is valid under the assumption that the magnitude of the average effect at a locus is proportional to the reciprocal of the square root of expected heterozygosity at that locus,

| (A8) |

Equation A7 shows that elements of G_VR2 are the genome-wide average of the correlations at individual loci; the term in square brackets is the correlation between additive genetic effects at locus l, and the sum of these terms is divided by the number of loci. Thus G_VR2 may have been motivated as the genome-wide average of relationships at individual loci.

However, relatedness refers to the correlation between the total additive genetic effects of individuals (Equation A2), which are sums of additive genetic effects at individual loci. In general, the correlation between sums does not equal the average correlation between components of the sums,

| (A9) |

but is defined as the ratio of the covariance and variance of the sum,

| (A10) |

Equation A9 and Equation A10 are only equal to each other under the assumption given in Equation A1.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. Sillanpaa

Literature Cited

- Bohren B. B., Hill W. G., Robertson A., 1966. Some observations on asymmetrical correlated responses to selection. Genet. Res. 7: 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. C., Ye C. J., Price A. L., Zaitlen N., 2016. Transethnic genetic-correlation estimates from summary statistics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99: 76–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik-Sullivan B., Finucane H. K., Anttila V., Gusev A., Day F. R., et al. , 2015. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 47: 1236–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer M. G., 1971. The effect of selection on genetic variability. Am. Nat. 105: 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Schenkel F., Vinsky M., Crews D., Li C., 2013. Accuracy of predicting genomic breeding values for residual feed intake in Angus and Charolais beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 91: 4669–4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Li C., Miller S., Schenkel F., 2014. Multi-population genomic prediction using a multi-task Bayesian learning model. BMC Genet. 15: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daetwyler H. D., Calus M. P. L., Pong-Wong R., De los Campos G., Hickey J. M., 2013. Genomic prediction in animals and plants: simulation of data, validation, reporting, and benchmarking. Genetics 193: 347–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Candia T. R., Lee S. H., Yang J., Browning B. L., Gejman P. V., et al. , 2013. Additive genetic variation in schizophrenia risk is shared by populations of African and European descent. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93: 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbe M., Hayes B. J., Matukumalli L. K., Goswami S., Bowman P. J., et al. , 2012. Improving accuracy of genomic predictions within and between dairy cattle breeds with imputed high-density single nucleotide polymorphism panels. J. Dairy Sci. 95: 4114–4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer D. S., 1952. The problem of environment and selection. Am. Nat. 86: 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer D. S., Mackay T. F. C., 1996. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. A., 1918. The correlation between relatives on the supposition of Mendelian inheritance. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 52: 399–433. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. A., 1930. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Flint-Garcia S. A., Thornsberry J. M., Buckler E. S., IV, 2003. Structure of linkage disequilibrium in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54: 357–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier M., Faraut T., Moazami-Goudarzi K., Navratil V., Foglio M., et al. , 2007. Genetic and haplotypic structure in 14 European and African cattle breeds. Genetics 177: 1059–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianola D., De los Campos G., Toro M. A., Naya H., Schön C.-C., et al. , 2015. Do molecular markers inform about pleiotropy? Genetics 201: 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour A. R., Gogel B. J., Cullis B. R., Welham S. J., Thompson R., 2015. ASReml User Guide Release 4.1. VSN International Ltd, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M. E., 2009. Genomic selection: prediction of accuracy and maximisation of long term response. Genetica 136: 245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habier D., Fernando R. L., Dekkers J. C. M., 2007. The impact of genetic relationship information on genome-assisted breeding values. Genetics 177: 2389–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane J. B. S., 1924. A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection—I. Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc. 23: 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. L., Johnson D. L., 2010. Genomic predictions for New Zealand dairy bulls and integration with national genetic evaluation. J. Dairy Sci. 93: 1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes B. J., Visscher P. M., Goddard M. E., 2009. Increased accuracy of artificial selection by using the realized relationship matrix. Genet. Res. 91: 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz E. M., Fulton J. E., O’Sullivan N., Zhao H., Dekkers J. C. M., et al. , 2005. Extent and consistency across generations of linkage disequilibrium in commercial layer chicken breeding populations. Genetics 171: 1173–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C. R., 1984. Applications of Linear Models in Animal Breeding. University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Jorjani H., Klei L., Emanuelson U., 2003. A simple method for weighted bending of genetic (co)variance matrices. J. Dairy Sci. 86: 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoui S., Carabaño M., Díaz C., Legarra A., 2012. Joint genomic evaluation of French dairy cattle breeds using multiple-trait models. Genet. Sel. Evol. 44: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krag K., Poulsen N. A., Larsen M. K., Larsen L. B., Janss L. L., et al. , 2013. Genetic parameters for milk fatty acids in Danish Holstein cattle based on SNP markers using a Bayesian approach. BMC Genet. 14: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legarra A., 2016. Comparing estimates of genetic variance across different relationship models. Theor. Popul. Biol. 107: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehermeier C., Krämer N., Bauer E., Bauland C., Camisan C., et al. , 2014. Usefulness of multiparental populations of maize (Zea mays L.) for genome-based prediction. Genetics 198: 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehermeier C., Schön C.-C., De los Campos G., 2015. Assessment of genetic heterogeneity in structured plant populations using multivariate whole-genome regression models. Genetics 201: 323–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco D. A. L., Tsuruta S., Fragomeni B. O., Chen C. Y., Herring W. O., et al. , 2016. Crossbreed evaluations in single-step genomic best linear unbiased predictor using adjusted realized relationship matrices. J. Anim. Sci. 94: 909–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makgahlela M. L., Strandén I., Nielsen U. S., Sillanpää M. J., Mäntysaari E. A., 2013. The estimation of genomic relationships using breedwise allele frequencies among animals in multibreed populations. J. Dairy Sci. 96: 5364–5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makgahlela M. L., Strandén I., Nielsen U. S., Sillanpää M. J., Mäntysaari E. A., 2014. Using the unified relationship matrix adjusted by breed-wise allele frequencies in genomic evaluation of a multibreed population. J. Dairy Sci. 97: 1117–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen T. H. E., Hayes B. J., Goddard M. E., 2001. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics 157: 1819–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson K. M., VanRaden P. M., Tooker M. E., 2012. Multibreed genomic evaluations using purebred Holsteins, Jerseys, and Brown Swiss. J. Dairy Sci. 95: 5378–5383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargolzaei M., Schenkel F. S., 2009. QMSim: a large-scale genome simulator for livestock. Bioinformatics 25: 680–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S. L., Mukherjee N., Pakstis A. J., Feuk L., Kidd J. R., et al. , 2005. Linkage disequilibrium patterns vary substantially among populations. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 13: 677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen L. P., Janss L., Madsen P., Mark T., Lund M. S., 2012. Estimation of (co)variances for genomic regions of flexible sizes: application to complex infectious udder diseases in dairy cattle. Genet. Sel. Evol. 44: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed D., Balding D. J., 2015. Relatedness in the post-genomic era: is it still useful? Nat. Rev. Genet. 16: 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandén I., Christensen O. F., 2011. Allele coding in genomic evaluation. Genet. Sel. Evol. 43: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technow F., Totir L. R., 2015. Using bayesian multilevel whole genome regression models for partial pooling of training sets in genomic prediction. G3 5: 1603–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRaden P. M., 2008. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 91: 4414–4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veroneze R., Lopes P. S., Guimarães S. E. F., Silva F. F., Lopes M. S., et al. , 2013. Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype block structure in six commercial pig lines. J. Anim. Sci. 91: 3493–3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher P. M., Hemani G., Vinkhuyzen A. A. E., Chen G.-B., Lee S. H., et al. , 2014. Statistical power to detect genetic (co)variance of complex traits using SNP data in unrelated samples. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wientjes Y. C. J., Veerkamp R. F., Bijma P., Bovenhuis H., Schrooten C., et al. , 2015. Empirical and deterministic accuracies of across-population genomic prediction. Genet. Sel. Evol. 47: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wientjes Y. C. J., Bijma P., Veerkamp R. F., Calus M. P. L., 2016. An equation to predict the accuracy of genomic values by combining data from multiple traits, breeds, lines, or environments. Genetics 202: 799–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S., 1931. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16: 97–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S., 1937. The distribution of gene frequencies in populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 23: 307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Benyamin B., McEvoy B. P., Gordon S., Henders A. K., et al. , 2010. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 42: 565–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Lund M. S., Wang Y., Su G., 2014. Genomic predictions across Nordic Holstein and Nordic Red using the genomic best linear unbiased prediction model with different genomic relationship matrices. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 131: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplemental Material, File S1, contains the R-script and seeds to simulate genotypes and phenotypes and to calculate G matrices for the scenario with causal loci in LE. File S2 contains the QMSim input file, R-script, and seeds to simulate genotypes and phenotypes and to calculate G matrices for the scenario with causal loci in LD.