Abstract

This viewpoint reviews the perspectives for dermatology as a specialty to go beyond the substantial impact of smoking on skin disease and leverage the impact of skin changes on a person's self-concept and behavior in the design of effective interventions for smoking prevention and cessation.

Keywords: dermatology, smoking, apps, photoaging, face, skin, tobacco, tobacco cessation, tobacco prevention

Most smokers start smoking during their early adolescence, often with the idea that smoking is glamorous; the problems related to impaired wound healing, erectile dysfunction, and oral cancers are too far in the future to fathom. In contrast, for the majority of teenagers, attractiveness is the most important predictor of their own self-esteem [1].

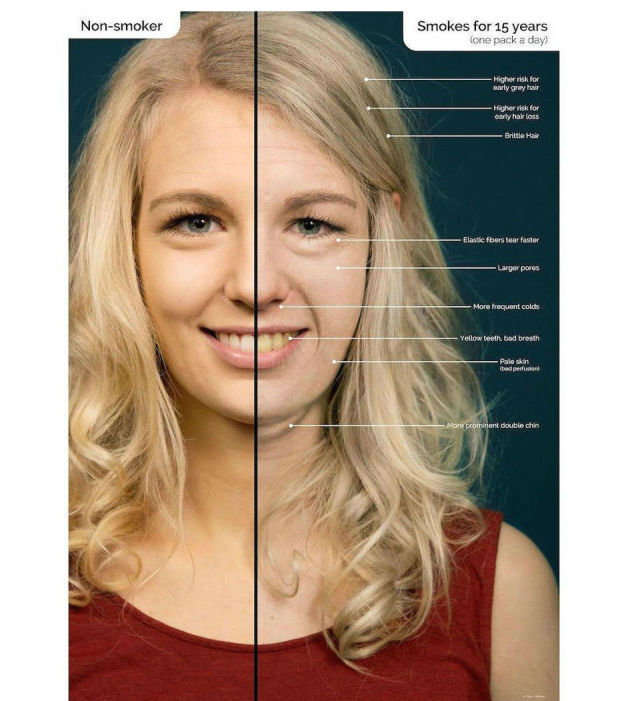

Interventions focusing on the negative dermatologic changes due to smoking have been effective in altering behavior, both in adolescence [2-4] and young adulthood [5,6]. Skin damage due to smoking that is culturally associated with a decrease in attractiveness (ie, wrinkles, early hair loss, declined capillary perfusion, pale or grayish skin [7-9]) predominantly affects the self-concept of young people with low education [1], who are at significantly greater risk for tobacco addiction [10-12] and benefit the most from abstinence [13]. After reviewing the evidence regarding facial changes due to smoking on PubMed, we designed Figure 1 in order to extrapolate the typical appearance of a smoker’s face as frequently seen and noted by dermatologists.

Figure 1.

Normal aging versus effects of smoking a pack a day for 15 years.

First steps have been taken to disseminate this dermatologic knowledge on irreversible aesthetic damage to the target groups and measure its effectiveness in randomized trials (ie, via the free photoaging app Smokerface, in which a selfie is altered to predict future appearance) in Germany [3,4,14,15] and Brazil [16] with a total of more than 150,000 downloads. In addition, photoaging desktop-based interventions in France [6], Switzerland [2], and Australia [5] showed promising results that justify definitive randomized trials. The relevance of skin-based appearance for individual behavior was also confirmed in the setting of skin cancer prevention [4,17-21].

Dermatology as an interdisciplinary specialty needs to go beyond the substantial impact of smoking on skin disease [22,23] and leverage the impact of skin changes on a person’s self-concept [1] and behavior [5] in the design of effective interventions for the largest cause of preventable death and disease in the western world [24]. Future dermatologic research should focus on developing, evaluating, and optimizing new ways to implement the specialty’s superior ammunition in the war against smoking.

References

- 1.Baudson T, Weber K, Freund PA. More than only skin deep: appearance self-concept predicts most of secondary school students' self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1568. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01568. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss C, Hanebuth D, Coda P, Dratva J, Heintz M, Stutz EZ. Aging images as a motivational trigger for smoking cessation in young women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010 Dec;7(9):3499–3512. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7093499. http://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph7093499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinker T, Owczarek A, Seeger W, Groneberg D, Brieske C, Jansen P, Klode J, Stoffels I, Schadendorf D, Izar B, Fries FN, Hofmann FJ. A medical student-delivered smoking prevention program, education against tobacco, for secondary schools in Germany: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Jun 06;19(6):e199. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7906. http://www.jmir.org/2017/6/e199/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinker TJ, Seeger W, Buslaff F. Photoaging mobile apps in school-based tobacco prevention: the mirroring approach. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Jun 28;18(6):e183. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6016. http://www.jmir.org/2016/6/e183/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burford O, Jiwa M, Carter O, Parsons R, Hendrie D. Internet-based photoaging within Australian pharmacies to promote smoking cessation: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Mar 26;15(3):e64. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2337. http://www.jmir.org/2013/3/e64/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burford O, Kindarji S, Parsons R, Falcoff H. Using visual demonstrations in young adults to promote smoking cessation: preliminary findings from a French pilot study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017 May 04;:1. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada H, Alleyne B, Varghai K, Kinder K, Guyuron B. Facial changes caused by smoking: a comparison between smoking and nonsmoking identical twins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1085–1092. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c20a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupati A, Helfrich YR. Effect of cigarette smoking on skin aging. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2009;4(4):371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin L, Morita A, Tsuji T. Skin aging induced by ultraviolet exposure and tobacco smoking: evidence from epidemiological and molecular studies. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2001 Aug;17(4):178–183. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2001.170407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J Health Econ. 2010 Jan;29(1):1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19963292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoebel J, Kuntz B, Kroll L, Finger J, Zeiher J, Lange C, Lampert T. Trends in absolute and relative educational inequalities in adult smoking since the early 2000s: the case of Germany. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017 Apr 18;:1. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuntz B, Lampert T. Smoking and passive smoke exposure among adolescents in Germany: prevalence, trends over time, and differences between social groups. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(3):23–30. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328(7455):50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinker TJ, Holzapfel J, Baudson TG, Sies K, Jakob L, Baumert HM, Heckl M, Cirac A, Suhre JL, Mathes V, Fries FN, Spielmann H, Rigotti N, Seeger W, Herth F, Groneberg DA, Raupach T, Gall H, Bauer C, Marek P, Batra A, Harrison CH, Taha L, Owczarek A, Hofmann FJ, Thomas R, Mons U, Kreuter M. Photoaging smartphone app promoting poster campaign to reduce smoking prevalence in secondary schools: the Smokerface Randomized Trial: design and baseline characteristics. BMJ Open. 2016 Nov 07;6(11):e014288. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014288. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=27821601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinker T, Seeger W. Photoaging mobile apps: a novel opportunity for smoking cessation? J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(7):e186. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xavier L, Bernardes-Souza B, Lisboa O, Seeger W, Groneberg D, Tran T, Fries F. A medical student-delivered smoking prevention program, Education Against Tobacco, for secondary schools in Brazil: study protocol for a randomized trial. JMIR Research Protocols 2017. 2017;6(1):e16. doi: 10.2196/resprot.7134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinker TJ, Schadendorf D, Klode J, Cosgarea I, Rösch A, Jansen P, Stoffels I, Izar B. Photoaging mobile apps as a novel opportunity for melanoma prevention: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017 Jul 26;5(7):e101. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8231. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2017/7/e101/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Starr P, Dietrich AJ. The impact of an appearance-based educational intervention on adolescent intention to use sunscreen. Health Educ Res. 2008 Oct;23(5):763–769. doi: 10.1093/her/cym005. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18039727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen A, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D. Effects of an appearance-focussed versus a health-focussed intervention on men's attitudes towards UV exposure. Int J Men Health. 2016;15(1):34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuong W, Armstrong AW. Effect of appearance-based education compared with health-based education on sunscreen use and knowledge: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(4):665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinker T, Brieske Christian Martin, Schaefer Christoph Matthias, Buslaff Fabian, Gatzka Martina, Petri Maximilian Philip, Sondermann Wiebke, Schadendorf Dirk, Stoffels Ingo, Klode Joachim. Photoaging Mobile Apps in School-Based Melanoma Prevention: Pilot Study. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Sep 08;19(9):e319. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8661. http://www.jmir.org/2017/9/e319/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz A, Grando SA. Smoking and the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2012 Mar;51(3):250–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dusingize J, Olsen C, Pandeya N, Subramaniam P, Thompson B, Neale R, Green A, Whiteman D. Cigarette smoking and the risks of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Aug;137(8):1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017 May 13;389(10082):1885–1906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]