Summary

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a major manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), causing morbidity and mortality in 40–60% of SLE patients. The pathogenic mechanisms of LN are not completely understood. Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of various immune cell populations in lupus nephritic kidneys of both SLE patients and lupus‐prone mice. These cells may play important pathogenic or regulatory roles in situ to promote or sustain LN. Here, using lupus‐prone mouse models, we showed the pathogenic role of a kidney‐infiltrating CD11c+ myeloid cell population in LN. These CD11c+ cells accumulated in the kidneys of lupus‐prone mice as LN progressed. Surface markers of this population suggest their dendritic cell identity and differentiation from lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)low mature monocytes. The cytokine/chemokine profile of these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells suggests their roles in promoting LN, which was confirmed further in a loss‐of‐function in‐vivo study by using an antibody‐drug conjugate (ADC) strategy targeting CX3CR1, a chemokine receptor expressed highly on these CD11c+ cells. However, CX3CR1 was dispensable for the homing of CD11c+ cells into lupus nephritic kidneys. Finally, we found that these CD11c+ cells co‐localized with infiltrating T cells in the kidney. Using an ex‐ vivo co‐culture system, we showed that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells promoted the survival, proliferation and interferon‐γ production of renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells, suggesting a T cell‐dependent mechanism by which these CD11c+ cells promote LN. Together, our results identify a pathogenic kidney‐infiltrating CD11c+ cell population promoting LN progression, which could be a new therapeutic target for the treatment of LN.

Keywords: CD11c+ cells, CX3CR1, lupus nephritis, MRL/lpr, T cells

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease induced by the breach of systemic immunotolerance to self‐antigens that are typically nuclear components and phospholipids 1, 2. It manifests as persistent inflammation in multiple organs, including kidney, lung, skin, heart, joints and brain 3. Among different manifestations, lupus nephritis (LN; inflammation of the kidney), occurs in approximately 50% of SLE patients and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in SLE patients 4. Commonly used anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive chemical drugs have prolonged the survival of patients with LN significantly 3, but systemic side effects are a major cause of concern. Recently, several antibody‐based products aimed to perturb specific immune reactions have been developed and evaluated in clinical trials to reduce or replace the use of chemical drugs 3, 5, 6. However, these treatments are not so specific for autoimmune reactions that they can compromise the normal immune response to infections 7, 8. In addition, some LN patients are resistant to current standard‐of‐care treatments or experience relapses of symptoms 9. Therefore, it is urgent and necessary to continue investigating the kidney‐specific immune mechanisms behind LN, which may lead to the development of more effective drugs with fewer side effects.

LN is known to be initiated by renal deposition of high‐affinity autoantibodies generated by activated autoreactive B cells with the help from activated autoreactive T cells 3, 10. However, the downstream immune mechanisms causing the progression of LN are not well understood. Studies have shown that different types of leucocytes, including various T cell subsets, B cells, plasma cells, natural killer cells, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils, are accumulated in the kidneys of both patients and lupus‐prone mice with active LN 11, 12. Using lupus‐prone mice, one study demonstrated further that LN could still develop in the absence of humoral immune responses, and such development was associated with leucocyte infiltrations in the kidney 13. This highlights the critical roles of cellular immune responses in LN progression.

Among different renal‐infiltrating cell types, DCs are of interest because there are many subtypes of DCs, and each of them has specific and diverse immune functions through interacting with other immune cells 14. As a general surface marker for DCs, CD11c has been utilized in lupus‐prone mice to demonstrate the pathogenic roles of CD11c+ cells in SLE, particularly in the development of LN 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. However, as CD11c is also expressed on some macrophages 14, it is unclear whether the pathogenic CD11c+ cells belong to DCs, and if they do, which subpopulation(s) of DCs are more important for LN progression. Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), a subpopulation of DCs, have been demonstrated to be critical in initiating autoimmune responses in SLE by producing interferon (IFN)‐α 17, 18. Unlike pDCs, the role of conventional DCs (cDCs) subsets in LN remains unclear. The aim of this study was to reveal the pathogenic roles of cDCs in the development of LN. Here, using lupus‐prone mice, we show that a subpopulation of CD11c+ cells with surface markers representing mature monocyte‐derived cDCs accumulates in lupus nephritic kidneys, and has a pathogenic role in promoting LN, at least partially, by enhancing kidney‐infiltrating T cell responses.

Materials and methods

Mice

Murphy Roths large (MRL)/Mp (MRL), MRL/Mp‐Faslpr (MRL/lpr), New Zealand white (NZW)/Lac (NZW), NZBWF1 (NZB/W) and B6‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained in a specific pathogen‐free facility following the requirements of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. MRL and MRL/lpr are classical mouse models of LN. Mice with an MRL background possess multiple SLE susceptibility loci and exhibit autoimmune disorders similar to SLE‐associated manifestations in humans. With the spontaneous mutation Faslpr, MRL/lpr mice show lymphadenopathy and glomerulonephritis early in life. Female MRL/lpr mice die at an average age of 16 weeks. These mice develop severe kidney disease, with proteinuria detectable starting at 8 weeks of age. In contrast, the parent and control strain (MRL) does not show any sign of kidney disease before 18 weeks of age. Nevertheless, the MRL mouse is another lupus‐prone mouse model that develops kidney disease at approximately 9 months of age. Like MRL and MRL/lpr mice, NZB/W mice display high levels of anti‐nuclear antibodies, proteinuria and glomerulonephritis. The time–course of LN in NZB/W mice is similar to that in MRL mice.

Leucocyte isolation

For kidney leucocytes, kidneys were cut into 1–2 mm3 pieces and digested in 5 ml digestion buffer [10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM HEPES, 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0·2 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma‐Aldrich) in RPMI‐1640 medium] for 30 min at 37°C with gentle shaking. Ice‐cold ×1 phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS, 10 ml) containing 10 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) was added, followed by another 5 min of incubation on ice. After being vortexed several times, tissue pieces were filtered, smashed and washed twice with wash buffer [0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 mM EDTA and 10 mM Hepes in ×1 Hanks's balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+, all from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA] through 70‐μm cell strainers. The flow‐through solution containing cells was then centrifuged. The cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml 37% stock isotonic Percoll (SIP) solution (100% SIP was made by mixing 9 vols Percoll with 1 vol ×10 PBS; then the 100% SIP was diluted with wash buffer to make 70% SIP and 37% SIP) and layered carefully on top of 5 ml 70% SIP. After 30 min continuous centrifugation at 1000 g at room temperature, enriched leucocytes were collected from the layer between 37 and 70% SIP. For bone marrow mononuclear cells, bones from both hind limbs of each mouse were cracked gently in a mortar containing PBS using a pestle. Bone marrow was released by gentle stirring after the addition of C10 medium [RPMI‐1640, 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% ×100 minimum essential medium (MEM) non‐essential amino acids, 10 mM HEPES, 55 μM 2‐mercaptoethanol, 2 mM L‐glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin, all from Life Technologies]. The suspension was cleared by passing through a 70‐μm sterile cell strainer and layered carefully on top of Ficoll‐Paque Plus (GE Healthcare, Pittsburg, PA, USA). After 30 min continuous centrifugation at 1363 g at room temperature, mononuclear cells in the buffy coat layer were collected. For direct flow cytometry detection, spleens and all lymph nodes in the mesenteric region (MLN) were collected and mashed in 70‐μm cell strainers with C10. For purification of splenic CD8+ cDCs, spleens were injected with 500 μl digestion buffer (as used in kidney digestion), cut into 1–2 mm3 pieces and digested in 5 ml digestion buffer for 30 min at 37°C with gentle shaking. Ice‐cold ×1 PBS containing 10 mM EDTA was added, followed by another 5 min of incubation on ice. After being pipetted several times, cell suspensions were filtered through a 70‐μm cell strainer. The remaining tissue pieces in the cell strainer were smashed and washed. For total splenocytes or purification of CD8+ DCs from the spleen, red blood cells were lysed with red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

In‐vivo antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) treatment

Anti‐mouse CX3CR1‐biotin (clone SA011F11; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and streptavidin–saporin (Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA, USA) were mixed at a 1 : 1 molar ratio to make ADC, according to the manufacturer's instructions. ADC was aliquoted and stored at −20°C. Six‐week‐old MRL/lpr females were divided randomly into two groups (ADC and control groups) with four mice in each group. ADC (6 μg per dose) or ×1 PBS was injected intravenously into each 8–15‐week‐old mouse weekly. Body weight and proteinuria score were monitored weekly. Mice were euthanized at 15 weeks to collect plasma, splenocytes, kidney leucocytes and kidney tissues for further study.

Ex‐vivo T cell stimulation in a co‐culture system

Isolated leucocytes from the kidneys of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr females were blocked with anti‐mouse CD16/32 (clone 93; eBioscience) and then stained with anti‐mouse CD45‐phycoerythrin (PE0 (clone 30‐F11; eBioscience), CD11c‐peridinin chlorophyll‐cyanin (PerCP‐Cy)5.5 (clone HL3; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), CD11b‐allophycocyanin (APC)‐Cy7 (clone M1/70; BD Biosciences), CD4‐APC (clone RM4–5; eBioscience) and CD8‐PE‐Cy7 (clone 53–6.7; BD Biosciences). CD45+ leucocytes were enriched further by anti‐PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Enriched leucocytes were resuspended in sorting buffer (2% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EDTA in ×1 PBS) containing 2 μM 4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI; Life Technologies) and sorted with BD FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). CD11c+ cells were sorted as DAPI–CD45+CD11c+CD11b+, CD4+ T cells were sorted as DAPI–CD45+CD11c–CD11b–CD4+CD8–, CD8+ T cells were sorted as DAPI–CD45+CD11c–CD11b–CD4–CD8+, and double‐negative (DN) T cells were sorted as DAPI–CD45+CD11c–CD11b–CD4–CD8–. For T cell stimulation, 1 × 105 CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and DN T cells were resuspended, respectively, in 200 μl C10 containing 2 μg/ml anti‐mouse CD28 (clone 37.51; BD Biosciences) and cultured in a 96‐well flat‐bottomed plate (Costar 3595, tissue culture treated non‐pyrogenic polystyrene) coated with 10 μg/ml anti‐mouse CD3 (clone 145–2C11; BD Biosciences) for 3 days. Supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C. For co‐culture experiments, sorted CD4+ T cells were stained with 5 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE). CD4+ T cells (1 × 105/well), either alone or mixed with 5 × 104 CD11c+ cells, were resuspended in 200 μl C10 containing 2 μg/ml anti‐mouse CD28, 50 ng/ml mouse macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M‐CSF; Sigma‐Aldrich) and 5 μM oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) 1585 cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) or 5 μg/ml Imiquimod (InvivoGen) and cultured in a 96‐well flat‐bottomed plate coated with 10 μg/ml anti‐mouse CD3 for 3 days. Cells were collected for flow cytometry and supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Kidneys were embedded in Tissue‐Tek® OCT™ Compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and frozen rapidly in a freezing bath of dry ice and 2‐methylbutane. Frozen OCT samples were cryosectioned and unstained slides were stored at −80°C. Frozen slides were warmed to room temperature and allowed to dry for 30 min, followed by fixation in −20°C cold acetone at room temperature for 10 min. After washing in PBS, slides were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA and anti‐mouse CD16/32 for 20 min at room temperature. Slides were then incubated with fluorochrome‐conjugated antibody mixture for 1 h at room temperature in a dark humid box. Slides were mounted with Prolong Gold containing DAPI (Life Technologies). The following anti‐mouse antibodies were used in immunohistochemical analysis: CD11c‐PE (clone N418; eBioscience), CD3‐fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (clone 145–2C11; eBioscience). Slides were read and pictured with EVOS® FL microscope (Advanced Microscopy Group, Grand Island, NY, USA) and a ×20 objective (LPlanFL PH2 20x/0.4, ∞/1.2). All infiltrating areas of CD11c+ cells and CD3+ cells were captured and analysed with ImageJ software version 1·47v.

Flow cytometry

For surface marker staining, cells were blocked with anti‐mouse CD16/32 (eBioscience), stained with fluorochrome‐conjugated antibodies, and analysed with BD fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Aria II (BD Biosciences) or Attune NxT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) flow cytometer. Anti‐mouse antibodies used in this study include eBioscience: CD3‐biotin (clone 145–2C11), CD19‐biotin (clone 1D3), CD11c‐biotin (clone N418), CD11c‐PE, CD11b‐PerCP‐Cy5.5 (clone M1/70), CD45‐FITC (clone, 30‐F11), CD45‐PE, CD80‐PE (clone RMMP‐1), CD103‐APC (clone 2E7) and F4/80‐eFluor 450 (clone BM8); Biolegend: CD16–2 (FcgR IV)‐APC (clone 9E9), CD40‐APC (clone 3.23), CD44‐APC‐Cy7 (clone IM7), CD64 (FcgR I)‐PE (clone X54–5/7.1), CD138‐APC (clone 281–2), CD49b‐biotin (clone DX5), programmed death ligand 1 (PD‐L1)‐APC (clone 10F.9G2), inducible co‐stimulator ligand‐phycoerythrin (ICOSL‐PE) (clone HK5.3), immunoglobulin (Ig)G‐APC (clone poly4053), IgG2a‐PE (clone RMG2a‐62), CCR2‐PE (clone SA203G11), CX3CR1‐biotin, CX3CR1‐PE (clone SA011F11) and CX3CR1‐APC (clone SA011F11); BD Biosciences: B220‐V500 (clone RA3–6B2), CD4‐PE‐Cy7 (clone RM4–5), CD8a‐V450 (clone 53–6.7), CD11b‐APC‐Cy7, CD11c‐PerCP‐Cy5.5, CD11c‐BV510 (clone HL3), CD45‐APC‐Cy7 (clone 30‐F11), CD86‐PE (clone GL1), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)‐PE‐Cy7 (clone AL‐21), I‐E/I‐A‐BV421 (clone M5/114), I‐E/I‐A‐V500 (clone M5/114), OX40L‐BV421 (clone RM134L) and PD‐L2‐BV510 (clone TY25); Miltenyi Biotec: CD3‐APC (clone 145–2C11), CD115‐PE (clone AFS98), anti‐biotin‐FITC, anti‐biotin‐APC and Ly6G‐biotin (clone 1A8). Flow cytometry data were analysed with FlowJo version 10.2.

Reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR)

Bone marrow neutrophils were sorted as DAPI–Ly6G+CD11b+ cells. Bone marrow monocytes were sorted as DAPI–CD11c–CD11b+CD115+Ly6Chigh cells. Spleen CD8+ cDCs were pre‐enriched by staining with anti‐mouse CD11c‐biotin and anti‐biotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), then sorted further as DAPI–CD11b–CD11c+CD8+major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II+ cells. Kidney neutrophils were sorted as DAPI–CD45+Lin (CD3, CD19 and CD49b)–CD11c–CD11b+SSC‐Hhigh cells. Kidney monocytes were sorted as DAPI–CD45+Lin–CD11c–CD11b+Ly6Chigh cells. Kidney CD11c+ cells were sorted as DAPI–CD45+Lin–CD11c+CD11b+ cells. Total RNA from sorted cell populations was extracted with RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturers' instructions. Reverse transcription was performed by using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed with iTaq™ Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio‐Rad) and ABI 7500 Fast Real‐Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA). Relative quantities were calculated using L32 as the housekeeping gene. Primer sequences for RT–qPCR can be found in the supplementary materials (Supporting Information, Table S1).

Speed congenic back‐crossing to generate MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1‐knock‐out mice

B6‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice were bred with MRL/lpr mice to generate F1 mice. The F1 generation was intercrossed to generate Faslpr/lprCX3CR1gfp/gfp F2 mice determined by the genotyping of Fas and Cx3cr1 genes. Starting from the selected F2 mice, each subsequent generation was back‐crossed with MRL/lpr mice and selected by speed congenic strategy 21 plus the Cx3cr1 gene to obtain CX3CR1gfp/+ mice with a maximal MRL/lpr genetic background. The tail tips of the mice were used to extract gDNA by the Quick DNA purification protocol from The Jackson Laboratory. Genotyping of the Fas (wild‐type and Faslpr mutation) and Cx3cr1 genes (wild‐type and CX3CR1gfp replacement) was also performed following the protocols from The Jackson Laboratory. Speed congenic PCR was performed by using the following steps: (1) 94°C, 3 min; (2) (94°C, 20 s; 57°C, 15 s, −1°C/cycle; 68°C, 1 min) ×10 cycles; (3) (94°C, 15 s; 47°C, 15 s; 72°C, 1 min) ×28 cycles; and (4) 72°C, 2 min. KAPA2G Robust HotStart ReadyMix PCR Kit with dye (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) was used for the PCR. Primer sequences can be found in the supplementary materials (Supporting Information, Table S2). Tail tips of three fifth generation CX3CR1gfp/+ mice were sent to The Jackson Laboratory for single‐nucleotide polymorphism screen to determine the purity of the MRL background.

Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Blood was collected into anti‐coagulant (potassium EDTA)‐coated Capiject tubes (Terumo Medical, Somerset, NJ, USA) and centrifuged at 15 000 g for 30 s. Plasma was collected and stored at −80°C. Detection of anti‐double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA) IgG was described previously 22. Total IgG concentrations were determined with mouse IgG ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA).

Proteinuria score and kidney histopathology

Proteinuria was measured weekly with Chemstrip 2GP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). A scale of 0–3 was used that corresponded to negative‐trace (0–20 mg/dl), 30 mg/dl, 100 mg/dl and ≥ 500 mg/dl total protein, respectively. Kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin immediately after isolation, paraffin‐embedded, sectioned and stained for periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) at the Histopathology Laboratory at Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine. Kidney slides were read using the Olympus BX43 microscope. Glomerular lesions were graded on a scale of 0–3 for increased cellularity, increased mesangial matrix, necrosis, percentage of sclerotic glomeruli and presence of crescents 23. Similarly, tubulointerstitial lesions were graded on a scale of 0–3 for interstitial mononuclear infiltration, tubular damage, interstitial fibrosis and vasculitis. Slides were scored by a board‐certified veterinary pathologist (T. E. C.) in a blinded fashion.

Statistical analysis

For the comparison of two groups, the unpaired Student's t‐test was used. For the comparison of more than two groups, one‐way analysis of variance (anova) and Tukey's post‐test were used. Results were considered statistically significant when P < 0·05. In some experiments, linear regression analysis and Grubbs' test for identification of outliers were used. All analyses were performed with Prism Graphpad software version 5.0b.

Results

Renal accumulation of CD11c+ myeloid cells as LN progresses

To study the possible influence of CD11c+ cells on LN, we first investigated their presence in the kidney of lupus‐prone mice. IHC staining of CD11c on the kidney sections of 4‐month‐old MRL control mice and MRL/lpr lupus‐prone mice showed that CD11c+ cells accumulated specifically in the kidney medulla of MRL/lpr but not MRL mice (Fig. 1a). As active LN has been established in 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice but not MRL mice 24, this result suggests that the renal accumulation of CD11c+ cells may be associated with LN progression. To quantify further these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, we performed flow cytometry on isolated renal leucocytes. Most renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells showed a CD45+Lin(CD3, CD19 and CD49b)–CD11b+CD11c+ phenotype (Fig. 1b), suggesting that they might be of myeloid lineage. The co‐expression of CD11c and CD11b was confirmed by IHC staining, with co‐localization of CD11c and CD11b signals in the kidney medulla of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice (Fig. 1c). Quantification of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in the kidney of MRL/lpr mice showed a significant increase of the cells from 6 to 15 weeks of age (Fig. 1d). Using the same gating strategy shown in Fig. 1b, we also found that both the percentage of CD11c+ cells in Lin– and their absolute cell numbers were much higher in the kidney of another lupus‐prone mouse model, NZB/W, compared to NZW controls, when NZB/W mice developed active LN at 35 weeks of age (Fig. 1e). While disease‐free at 4 months of age, MRL mice develop LN later in life (Supporting information, Fig. S1a), and is another classical model of LN. We found that in MRL mice, the percentage and absolute cell numbers of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells were increased at the age with active LN (37 weeks old) compared to younger ages (Fig. 1f). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the accumulation of CD11c+ cells in the nephritic kidney was a common phenotype shared by different lupus‐prone mouse models.

Figure 1.

Accumulation of a CD11c+ cell population in the kidney of lupus‐prone mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stains of CD11c+ cells (red) on the kidney sections of 4‐month‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL) and MRL/lpr mice. Representative images are shown. Blue, 4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI). (b) Stepwise gating of CD11c+ cells by flow cytometry as CD11c+CD45+Lin(CD3, CD19 and CD49b)–CD11b+ cells from isolated kidney mononuclear cells from MRL/lpr mice. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. (c) IHC stains of CD11c+ cells (red) and CD11b+ cells (green) on the kidney sections of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice. Representative images of the medulla region are shown. (d–f) The percentages of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in Lin– population (top row) as gated in (b) and the relative cell count changes of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (bottom row) in (d) 6‐week‐ and 15‐week‐old MRL/lpr mice, (e) 35‐week‐old New Zealand white (NZW) mice and NZB/W mice, and (f) 6‐week‐, 19‐week‐ and 37‐week‐old MRL mice. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001, Student's t‐test for (d,e) and one‐way analysis of variance (anova) for (f). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.); n = 3 mice in each group. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

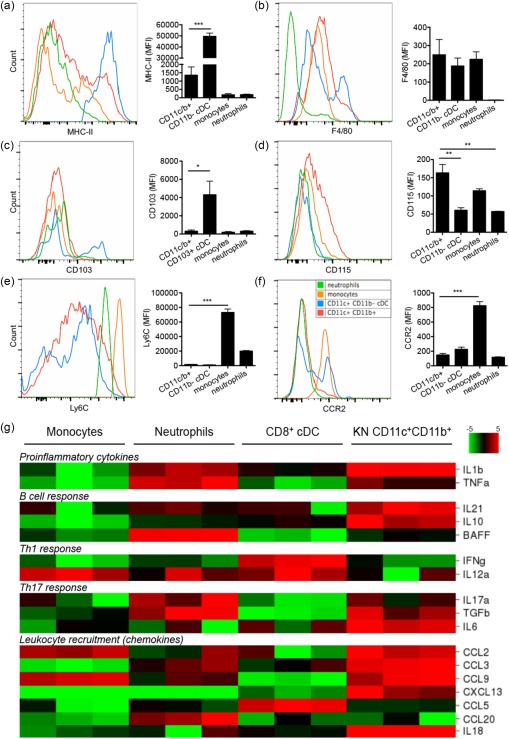

Renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells exhibiting a mature monocyte‐derived dendritic cell phenotype

To study further the possible origin of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, we included additional surface markers and compared their expression with neutrophils, monocytes and CD11b– cDC (see Supporting information, Fig. S1b for the gating strategy) from the same kidney as our model, using 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice. MHC‐II expression on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells was not uniform, with a majority of the population expressing a lower level of MHC‐II which, however, was still higher than that of neutrophils and monocytes (Fig. 2a). The rest of the CD11c+ population expressed a high level of MHC‐II that was comparable to that of mature CD11b– cDCs. In addition, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells expressed a low level of F4/80 (Fig. 2b), suggesting that these cells may be DCs instead of F4/80high macrophages. Moreover, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells were CD103–CD115high and different from CD103+CD115–CD11b– cDCs (Fig. 2c,d), suggesting that they may be derived from monocytes rather than cDC precursors. The Ly6ClowCCR2– phenotype of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, which was distinct from Ly6ChighCCR2+ immature monocytes, suggests further that they may be derived specifically from Ly6ClowCCR2– mature monocytes (Fig. 2e,f). Collectively, these results suggest that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells possessed a phenotype of mature monocyte‐derived DCs.

Figure 2.

Phenotype and cytokine/chemokine profile of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells. (a–f) The surface mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of (a) major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II, (b) F4/80, (c) CD103, (d) CD115, (e) Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C) and (f) CCR2 on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (CD11c+CD11b+, red), CD11b–conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) (defined as CD11c+CD11b–MHC‐II+, blue), monocytes (defined as CD11c–CD11b+Ly6ChighSSC‐Hlow, orange) and neutrophils (defined as CD11c–CD11b+Ly6CmidSSC‐Hhigh, green) from 4‐month‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL)/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histograms are shown. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n = 3 mice in each group. (g) Relative transcript levels of selected cytokines and chemokines as determined by reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR) in bone marrow monocytes [4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI)–CD11c–CD11b+CD115+Ly6Chigh], bone marrow neutrophils (DAPI–Ly6G+CD11b+), splenic CD8+cDCs (DAPI–CD11b–CD11c+CD8+MHC‐II+) and kidney (KN)‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (DAPI–CD45+Lin–CD11c+CD11b+) sorted from 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice. A heat‐map is shown. Red, higher expression level; green, lower expression level; n = 3 mice in each group. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As immature monocytes usually differentiate into inflammatory DCs, while mature monocytes regularly patrolling blood vessels are responsible for tissue repairs with anti‐inflammatory effects 25, 26, it is possible that these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells have anti‐inflammatory functions. Therefore, we sorted renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells from the kidney of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice and compared the transcript levels of several cytokines and chemokines with sorted bone marrow monocytes, bone marrow neutrophils and splenic CD8+ cDC from the same mice. To our surprise, these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells showed a much more complicated cytokine/chemokine profile, with the expression of both pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory molecules (Fig. 2g). Compared to bone marrow monocytes and splenic CD8+ cDC, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells expressed higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)‐1β, IL‐18 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF). At the same time, they also expressed high levels of anti‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β. In addition, the expression of IL‐10, together with that of IL‐21, can promote B cell responses, whereas the expression of TGF‐β and IL‐6 suggests their potential to promote T helper type 17 (Th17) responses. Moreover, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells highly expressed a set of chemokines, including CCL2, CCL3, CCL9, CXCL13 and IL‐18, that could attract the homing of monocytes, DC, T cells, B cells and pDCs into the kidney. Together, the cytokine and chemokine profile suggests that these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells might be pathogenic and could potentially promote LN.

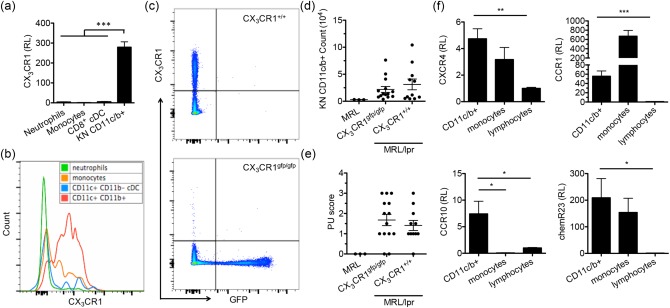

High expression of CX3CR1 on kidney‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells that is dispensable for renal homing

We next sought to determine the pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in vivo by blocking their infiltration into the kidney of MRL/lpr mice. The migration of leucocytes into specific tissues requires the expression of certain chemokine receptors 27. As the phenotype of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells suggested that they might be derived from mature monocytes, and that mature monocytes should express a high level of CX3CR1 on their surface 26, we measured the expression level of CX3CR1 on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells. As expected, these cells expressed CX3CR1 highly at both the transcriptional (Fig. 3a) and protein levels (Fig. 3b). To knock out CX3CR1, we performed speed congenic back‐crossing of B6‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice onto the MRL/lpr background by genotyping Faslpr (Supporting information, Fig. S1c), Cx3cr1 (Supporting information, Fig. S1d) and other SLE susceptibility loci, and generated MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp (CX3CR1gfp/gfp) and MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1+/+ (CX3CR1+/+) littermates after five generations of back‐crossing that achieved > 90% of MRL/lpr genetic background (data not shown). The replacement of CX3CR1 with green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the fifth generation was confirmed further by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 3c). Unexpectedly, at the age of 15 weeks, the absolute cell number of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice was not significantly different from that in MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1+/+ mice, although both of them were higher than that in age‐matched MRL control mice (Fig. 3d). Consistently, nor were the proteinuria scores different between MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp and MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1+/+ mice, and both were higher than that of MRL controls (Fig. 3e). Together, these results suggest that CX3CR1 may be dispensable for renal infiltration of CD11c+ cells and not critical for the development of LN in MRL/lpr mice. Further studies on other chemotactic receptors revealed that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells also expressed CXCR4, CCR1, CCR10 and chemR23 (Fig. 3f). CD11c+ cells may be able to use one or more of these receptors to infiltrate the nephritic kidneys of MRL/lpr mice.

Figure 3.

CX3CR1 highly expressed on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells but dispensable for their infiltration into the nephritic kidney. (a) The transcript level of CX3CR1 as determined by reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR) in bone marrow monocytes [4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI)‐CD11c– CD11b+CD115+lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)high], bone marrow neutrophils (DAPI–Ly6G+CD11b+), splenic CD8+ conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) [DAPI–CD11b–CD11c+CD8+ major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II+] and kidney (KN)‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (DAPI–CD45+Lin–CD11c+CD11b+) sorted from 4‐month‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL)/lpr mice. (b) The surface expression of CX3CR1 on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (CD11c+CD11b+, red), CD11b–cDCs (CD11c+CD11b–MHC‐II+, blue), monocytes (CD11c–CD11b+Ly6ChighSSC‐Hlow, orange) and neutrophils (CD11c–CD11b+Ly6CmidSSC‐Hhigh, green) from 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. A representative flow cytometry histogram is shown. (c) The expression of CX3CR1 and green fluorescent protein (GFP) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the fifth generation of MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1+/+ and MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp littermate mice as determined by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. (d) The absolute number of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in 15‐week‐old MRL, and the fifth generation of MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1+/+ and MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1gfp/gfp mice as determined by flow cytometry. (e) The proteinuria (PU) scores of the same three groups of mice. (f) The transcript levels of CXCR4, CCR1, CCR10 and chemR23 in renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (DAPI–CD45+Lin–CD11c+CD11b+), monocytes (DAPI–CD45+Lin–CD11c–CD11b+Ly6ChighSSC‐Hlow) and lymphocytes (DAPI–CD45+Lin+) sorted from the same kidneys of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by RT–qPCR. RL = relative level. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n ≥ 3 mice in each group. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

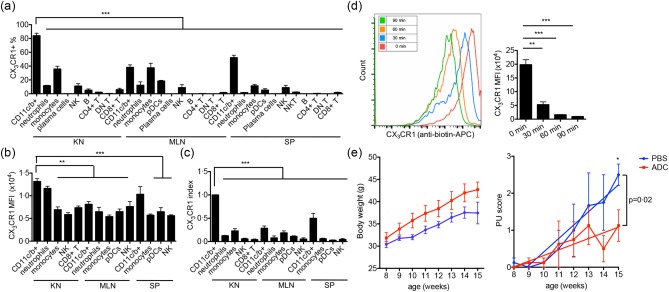

The pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in vivo

Although CX3CR1 is not critical for renal infiltration of CD11c+ cells, its high expression on these cells still suggests CX3CR1 as a good target for the removal or functional disruption of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells. We thus utilized an ADC method that has been used mainly in cancer therapies 28 to remove or disable renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in vivo. To exclude possible off‐target effects, we screened the expression of CX3CR1 on as many types of leucocytes as possible in the kidney, MLN and spleen of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice, and found that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells had the highest percentage of CX3CR1+ cells (Fig. 4a). We next compared the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CX3CR1 among leucocyte populations with > 5% of CX3CR1+ cells and found that, except for renal neutrophils and splenic CD11c+CD11b+ cells, the intensity of CX3CR1 on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells was significantly higher than that on all other cell types (Fig. 4b). Taking both the percentage and MFI of CX3CR1+ cells into consideration, we calculated the CX3CR1 expression index by multiplying the two, and showed that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells expressed a significantly higher level of CX3CR1 than all other cell types not only in the kidney, but also in the secondary immune tissues (Fig. 4c). This suggests that targeting CX3CR1 would specifically remove or disable renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells with very limited off‐target effects. Nevertheless, splenic CD11c+CD11b+ cells expressed the second highest level of CX3CR1 after renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (Fig. 4c) and could be a target of ADC. Another requirement for successful application of ADC is that target cells should internalize ADC efficiently after antibody binding to the target cells. To study the internalization of CX3CR1 after ligation with the anti‐CX3CR1 antibody, we stained renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells with anti‐CX3CR1‐biotin and incubated cells at 37°C for different time‐periods (0, 30, 60 or 90 min), allowing for the internalization of surface CX3CR1–anti‐CX3CR1‐biotin complexes. The cells were then stained with anti‐biotin‐APC to detect the remaining surface CX3CR1 by flow cytometry. The result showed a time‐dependent decrease of the APC signal on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (Fig. 4d), suggesting efficient internalization of CX3CR1 upon antibody ligation. With renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells expressing the highest level of CX3CR1, and knowing that CX3CR1 can be internalized effectively upon ligation with an anti‐CX3CR1 antibody, we concluded that CX3CR1 was a useful target for investigating the role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in LN by the ADC method.

Figure 4.

The pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in vivo. (a,b) The percentage of CX3CR1+ cells (a) and the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of CX3CR1 in the CX3CR1+ subpopulation (b) in each type of leucocytes from the kidney (KN), mesenteric lymph node (MLN) and spleen (SP) of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. (c) CX3CR1 expression index calculated as [(%CX3CR1+)cell type × (CX3CR1 MFI)CX3CR1+ part of cell type]/[(%CX3CR1+)renal CD11c+ cells × (CX3CR1 MFI)CX3CR1+ part of renal CD11c+ cells]. (d) Internalization of surface CX3CR1 by renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells from 4‐month‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL)/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with anti‐mouse CX3CR1‐biotin and cultured for different periods of time at 37°C, followed by staining with anti‐biotin‐allophycocyanin (APC). A representative flow cytometry histogram is shown. (e) Body weight (left) and proteinuria (PU) scores (right) of antibody–drug conjugate (ADC)‐ (red) or phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)‐ (blue) treated MRL/lpr mice. Mice were treated from 8 to 15 weeks old. *P < 0·05 **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova) or linear regression. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n ≥ 3 mice in each group. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The ADC we used in vivo was a monoclonal anti‐mouse CX3CR1‐saporin conjugate. In our study, we injected 6 μg ADC intravenously into each MRL/lpr mouse once a week starting from 8 to 15 weeks of age. The same volume of PBS was injected into control MRL/lpr mice. Weekly monitoring of mouse body weight and proteinuria scores revealed that the ADC‐treated group had higher body weight and significantly lower proteinuria scores at 15 weeks of age (Fig. 4e). In addition, linear regression analysis showed that the development of proteinuria was significantly slower in the ADC group than the PBS‐treated control group (Fig. 4e). The histopathological scores (glomerular score and tubulointerstitial score) were lower in the ADC group, but the difference was not statistically significant (Supporting information, Fig. S2a). To exclude the possible influence by the change of systemic autoimmune response, we measured the activation of T cells in the spleen (Supporting information, Fig. S2b) and antibody levels in the plasma (Supporting information, Fig. S2c). No difference was found between the ADC and PBS groups, suggesting that ADC did not affect the systemic autoimmune response, and that its effects were kidney‐specific. Collectively, these results indicate that ADC administration ameliorated LN in MRL/lpr mice without influencing systemic autoimmune response. As our ADC specifically targeted CX3CR1‐expressing renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, these results suggest the in‐vivo pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in the development of LN.

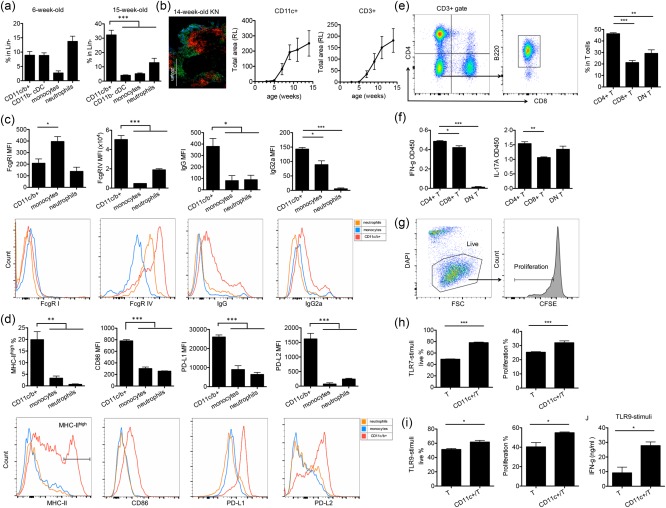

Promotion of renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cell response by syngeneic renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells

To study the mechanism by which renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells promote LN, we determined their interactions with renal‐infiltrating T cells that are known to be pathogenic in LN 29. Although many renal‐infiltrating innate immune cell types, including CD11b– cDCs, monocytes and neutrophils, can interact with T cells, we showed that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells outnumbered significantly the other innate immune cell populations in the kidney of MRL/lpr mice with active LN (15 weeks old) (Fig. 5a). This suggests that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells may be the predominant innate immune cell type interacting with T cells. Co‐staining of the kidney sections of MRL/lpr mice with CD11c and CD3 showed that CD11c+ cells and T cells localized in the same regions adjacent to each other. In addition, the time–courses of renal infiltration of CD11c+ cells and T cells were very similar (Fig. 5b), suggesting that they might interact or facilitate each other's infiltration into the kidney. As shown earlier, the renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells possessed the phenotype of DCs (Fig. 2a,b) that could interact with T cells as typical antigen‐presenting cells. We found that these CD11c+ cells expressed Fc‐gamma‐receptor type IV (FcgR‐IV) highly and were coated with IgG, in particular pathogenic IgG2a, on their surface (Fig. 5c), suggesting that they may be able to capture self‐antigen in the immune complexes. Moreover, the renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells expressed a high level of MHC‐II as well as a high ratio of CD86/CD80 (Supporting information, Fig. S2d,e, Fig. 5d), suggesting their potential ability to present self‐antigen to and stimulate autoreactive T cells. Furthermore, we found that these CD11c+ cells expressed co‐stimulatory molecules such as CD40, ICOSL and OX40L (Supporting information, Fig. S2f), which could provide additional activation signals for T cells. Interestingly, the renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells also expressed higher levels of co‐suppressive molecules PD‐L1 and PD‐L2 (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5.

The interaction between renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells and renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells. (a) The percentages of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+CD11b+ cells, CD11b– conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), monocytes and neutrophils in Lin– population of 6‐ and 15‐week‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL)/lpr mice. CD11c+CD11b+ cells were the predominant population in the kidney of 15‐week‐old mice with active lupus nephritis (LN). (b) Total renal infiltration areas of CD11c+ cells (red) and CD3+ T cells (green) from 3‐, 5‐, 7‐, 9‐, 11‐ and 14‐week‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and ImageJ quantification. RL = relative level. A representative image of the kidney (KN) of a 14‐week‐old MRL/lpr mouse is shown. Bar equals 200 μm. Blue, 4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI). (c,d) The surface level of Fc gamma receptor (FcgR) I, FcgR IV, immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgG2a, major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II, CD86, programmed death‐ligand 1(PD‐L1) and PD‐L2 on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (red), monocytes (orange) and neutrophils (blue) in the kidney of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry histograms are shown. (e) The percentages of renal‐infiltrating CD4+, CD8+ and CD4–CD8–B220+ double‐negative (DN) T cells in total renal‐infiltrating CD3+ T cells of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. The gating strategy is shown. (f) Interferon (IFN)‐γ and interleukin (IL)‐17a levels in the culture supernatant of CD4+, CD8+ and DN T cells stimulated with anti‐CD3/CD28 as determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (g–i) The percentages of live cells (DAPI–) and proliferating cells [carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)low] in renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells cultured alone or co‐cultured with renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells that were stimulated with anti‐CD3/CD28 and macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M‐CSF_ in the presence of (h) Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐7 agonist, Imiquimod or (i) TLR‐9 agonist, oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) 1585 cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG). Representative flow cytometry plots and the gating strategy are shown in (g). (j) IFN‐γ levels in the culture supernatant of renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells cultured alone or co‐cultured with renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells that are stimulated with anti‐CD3/CD28, M‐CSF and ODN 1585 CpG as determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova) for (a–f) and Student's t‐test for (h–j). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n = 3 mice in each group. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We next performed co‐culture experiments between renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells and syngeneic renal‐infiltrating T cells to study their interactions ex vivo. Three major T cell subpopulations, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and CD4–CD8–B220+ (DN) T cells, infiltrated the nephritic kidney of MRL/lpr mice. The number of CD4+ T cells was highest among the three subpopulations (Fig. 5e). In addition, upon ex‐vivo stimulation with anti‐CD3/CD28, CD4+ T cells were able to produce higher levels of two pathogenic cytokines, IFN‐γ and IL‐17a than CD8+ and DN T cells (Fig. 5f). We thus focused our attention on the interaction between CD11c+ cells and CD4+ T cells. In the co‐culture system, in addition to the presence of CD4+ T cells, we provided M‐CSF as a survival signal to renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, and stimulated CD11c+ cells with either Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐7 agonist, Imiquimod or TLR‐9 agonist, ODN1585 CpG to imitate self‐RNA or self‐DNA, respectively. Conversely, CD4+ T cells were stained with CFSE and stimulated with anti‐CD3/CD28. After three days of co‐culturing, we found that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells promoted both the survival (DAPI–) and proliferation (CFSElow) of CD4+ T cells compared to CD4+ T cells alone (Fig. 5h,i, with representative flow cytometry plots of DAPI and CFSE staining shown in Fig. 5g). Furthermore, when stimulated with a TLR‐9 agonist, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells also enhanced IFN‐γ production from CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5j). Taken together, our results suggest that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells were able to promote the activation of renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells, which may be one of the mechanisms by which these CD11c+ cells deteriorated LN in MRL/lpr mice.

Discussion

CD11c+ cells have been demonstrated to play pathogenic roles in the development of LN in lupus‐prone mice 15, 17, 18, 19. In addition, the accumulation of CD11c+ cells has been found in the kidney of both SLE patients and lupus‐prone mice with active LN 20, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. However, as CD11c+ cells are extremely heterogeneous, the spatial and temporal roles of different CD11c+ subsets in LN development have not been well investigated. In this study, we identified a population of DC‐like CD11c+ cells, which accumulated in the kidney of different types of lupus‐prone mice with active LN. We demonstrated that they were pathogenic in promoting proteinuria through enhancing renal‐infiltrating T helper cell responses in the MRL/lpr mouse model. The similar accumulation of CD11c+ cells in the nephritic kidney of both MRL and MRL/lpr mice suggests that the increase of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells and their pathogenic functions should be due to the multiple SLE susceptibility loci present in the MRL mouse background, rather than the Faslpr gene mutation in MRL/lpr mice. While the accumulation and subpopulations of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, especially CD11c+CD11b+ DCs, have also been studied in some other lupus‐prone mouse models by other groups 34, 35, in comparison the renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells we identified in MRL/lpr mice have shown both similarities and differences. Regarding F4/80 and MHC‐II expression, unlike the three subpopulations (F4/80+, F4/80–MHC‐II– and F4/80–MHC‐II+) of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+CD11b+ cells in SLE 1 transgenic TLR‐7 mice 35, those in the kidneys of MRL/lpr mice are all F4/80lowMHC‐II+ and similar to the renal‐infiltrating CD11c+CD11b+F4/80low cells identified in NZB/W F1 mice that express MHC‐II from low to high levels 34, suggesting that these cells belong to the same population with different activating status. Furthermore, combined with additional markers, these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells possessed a surface phenotype of mature monocytes, especially with a high expression of CX3CR1, which is consistent with studies in SLE patients where CX3CR1+ cells and CD16+ cells are found in the kidney biopsies of patients with active LN 36. The similar cell population found in NZB/W F1 mice, however, is negative for CX3CR1 expression 34. This suggests that different lupus‐prone mouse models have unique characteristics and our findings in MRL/lpr mice are clinically relevant, as the same population of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells are found in both MRL/lpr mice and SLE patients.

Notably, different from well‐accepted concepts that immature monocytes enhance the inflammation whereas mature monocytes down‐regulate inflammation 25, 26, mature monocytes in SLE patients have been suggested to possess a pathogenic role to promote lupus disease by enhancing pathogenic T cell responses 37. The results of the present study support this notion, as our cell population of interest, which is derived from mature monocytes, appears to be proinflammatory and contributes to disease pathogenesis in LN. Therefore, the functions of a particular cell type may change depending on the microenvironment.

In our study of MRL/lpr mice, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells expressed higher levels of MHC‐II and CD86/CD80 co‐stimulatory molecules than renal‐infiltrating monocytes and neutrophils, suggesting their activated state and ability to activate T helper cells, which was then confirmed by the ex‐vivo co‐culture experiments. Additionally, later co‐stimulatory molecules, ICOSL and OX40L in particular, also expressed by these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, have been demonstrated to be pathogenic through activating autoreactive T cells in both lupus‐prone mice and SLE patients 15, 16. However, renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells also expressed high levels of co‐suppressive molecules PD‐L1 and PD‐L2. As PD‐L1 and PD‐L2 are IFN‐γ‐inducible genes that can be up‐regulated on IFN‐γ‐activated APCs 38, this result is consistent with the activated state of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells and suggests their possible interaction with renal‐infiltrating T helper cells, in particular IFN‐γ‐producing pathogenic T helper cells. In addition, we found that renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells only expressed a low level of PD‐1 (data not shown), suggesting a limited suppressive effect of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells on renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cells. Indeed, the results of our ex‐vivo co‐culture experiments suggest that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells actually promoted the syngeneic renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cell response.

To investigate the potentially pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in vivo, we tried two different methods: CX3CR1‐knock‐out and ADC. Studies have shown that the interaction between CX3CR1 and its ligand CX3CL1 can promote LN in MRL/lpr mice 39 and that the interaction is responsible for the infiltration of pathogenic DCs into the kidney in a nephrotoxic nephritis mouse model 40. We thus hypothesized that by knocking out CX3CR1 from MRL/lpr mice, these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells would be unable to infiltrate into the kidney and LN would be ameliorated. However, these two strategies resulted in different outcomes, with no disease change in CX3CR1‐knock‐out mice but amelioration of LN in ADC‐treated mice. This suggests that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells are pathogenic, but their effects may be independent of CX3CR1. As the knock‐out of CX3CR1 failed to prevent their renal accumulation, the infiltration of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells appeared to be CX3CR1‐independent. This partially explains the unfavourable phenotype in MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1–/– mice. To exclude the influence of the remaining B6 genetic background (less than 10%) in the fifth generation of MRL/lpr‐CX3CR1–/– mice, we back‐crossed the mice further onto an MRL/lpr background for a total of 10 generations that achieved > 99% MRL/lpr genetic purity. Unfortunately, the severity and course of kidney disease were still unaffected (data not shown). Conversely, the ADC method targets renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells by directly depleting them or disabling their functions, and is thus a more effective way to demonstrate the in‐vivo pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in LN. The ADC used in this study was designed optimally to maximize its effects. The anti‐mouse CX3CR1 antibody was of mouse IgG2a origin to reduce host immune responses to ADC. Saporin is a very stable cytotoxic drug that functions by preventing protein synthesis in the cell. It has been used to induce apoptosis of tumour cells in cancer therapies 41. The potential off‐target effect of ADC treatment was a concern, as splenic CD11c+CD11b+ cells expressed the second highest level of CX3CR1, but we found that the activated T cells in the spleen and the levels of circulating antibodies including anti‐dsDNA antibodies were not different between ADC‐ and PBS‐treated groups. This suggests that ADC treatment did not affect systemic immune responses, and that the pathogenic role of renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells might be kidney‐specific.

The ADC strategy to target renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells appears to be efficacious in MRL/lpr mice. This can be highly translatable, where a similar ADC‐based drug may be used to target a similar population in LN patients with high efficiency and low side effects. However, further studies are required to characterize these renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells in the kidney of LN patients. For example, although the surface markers suggest their mature monocyte origin, this should be confirmed in vivo. In addition, it would be worthwhile to investigate further the molecular mechanisms by which renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells promote CD4+ T cell responses in vivo. Moreover, based on their cytokine/chemokine profile, it appears that renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells may be able to influence renal‐infiltrating monocytes 42, pDCs 43 and B cells 44, 45 in addition to CD4+ T cells. This would be also interesting to explore.

In conclusion, we identified a renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cell population associated with the progression of LN in different lupus‐prone mouse models. They had a phenotype of mature monocyte‐derived DCs with a complicated cytokine/chemokine profile. These renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells have shown a pathogenic role in promoting LN in MRL/lpr mice by partially enhancing syngeneic renal‐infiltrating CD4+ T cell responses. Moreover, their preferential surface expression of CX3CR1 makes them a potential therapeutic target. Our results could be highly translatable if a similar population of CD11c+ cells exists in the nephritic kidneys of SLE patients.

Disclosure

The authors declare no disclosures.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Fig. S1. (a) Proteinuria (PU) scores of 6‐, 19‐ and 37‐week‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL) mice. ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n = 3 mice in each group. (b) Gating strategy for renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (Lin–CD11c+CD11b+), CD11b– conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) (Lin–CD11c+CD11b–major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II+), monocytes (Lin‐CD11c‐CD11b+ lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)highSSC‐Hlow) and neutrophils (Lin–CD11c–CD11b+Ly6CmidSS‐Hhigh) as determined by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. (c) Genotyping of wild‐type (+) and mutated (lpr) Fas gene. (d) Genotyping of wild‐type (+) and mutated [green fluorescent protein (gfp)] Cx3cr1 gene.

Fig. S2. (a) Glomerular (left) and tubulointerstitial (right) scores of antibody–drug conjugate (ADC)‐ or phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)‐treated Murphy Roths large (MRL)/lpr mice at 15 weeks old. (b) The percentages of CD44+ activated cells in splenic CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells of ADC‐ or PBS‐treated MRL/lpr mice at 15 weeks old as determined by flow cytometry. (c) Total immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgG2a levels (top row) and anti‐dsDNA IgG and IgG2a levels (bottom row) in the plasma of ADC‐ or PBS‐treated MRL/lpr mice at 15 weeks old as determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (d,e) The percentages of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II+ population (d) and the expression of CD80 and the ratio of CD86 and CD80 mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) (e) in renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, monocytes and neutrophils of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. (f) The expression of CD40, inducible co‐stimulator ligand (ICOSL) and OX40L on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, monocytes, neutrophils and CD11c–CD11b– cells (mainly lymphocytes) of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n ≥ 3 mice in each group.

Table S1. List of primers for reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR).

Table S2. List of primers for speed congenic polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Acknowledgements

We thank Melissa Makris and Dr Caroline Leeth for the use of flow cytometry core facility at Virginia Tech. This work was supported by various internal grants awarded to XML. X. L. is a Stamps Fellow in the Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences graduate program.

References

- 1. Nacionales DC, Weinstein JS, Yan XJ et al B cell proliferation, somatic hypermutation, class switch recombination, and autoantibody production in ectopic lymphoid tissue in murine lupus. J Immunol 2009; 182:4226–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ching KH, Burbelo PD, Tipton C et al Two major autoantibody clusters in systemic lupus erythematosus. PLOS ONE 2012; 7:e32001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:2110–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Almaani S, Meara A, Rovin BH. Update on lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12:825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE et al Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011; 377:721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Merrill JT, Neuwelt CM, Wallace DJ et al Efficacy and safety of rituximab in moderately‐to‐severely active systemic lupus erythematosus: the randomized, double‐blind, phase II/III systemic lupus erythematosus evaluation of rituximab trial. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62:222–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Illei GG, Austin HA, Crane M et al Combination therapy with pulse cyclophosphamide plus pulse methylprednisolone improves long‐term renal outcome without adding toxicity in patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135:248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crispín JC, Liossis SN, Kis‐Toth K et al Pathogenesis of human systemic lupus erythematosus: recent advances. Trends Mol Med 2010; 16:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gibson KL, Gipson DS, Massengill SA et al Predictors of relapse and end stage kidney disease in proliferative lupus nephritis: focus on children, adolescents, and young adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4:1962–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yung S, Chan TM. Autoantibodies and resident renal cells in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis: getting to know the unknown. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:139365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nowling TK, Gilkeson GS. Mechanisms of tissue injury in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2011; 13:250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spada R, Rojas JM, Perez‐Yague S et al NKG2D ligand overexpression in lupus nephritis correlates with increased NK cell activity and differentiation in kidneys but not in the periphery. J Leukoc Biol 2015; 97:583–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chan OT, Hannum LG, Haberman AM, Madaio MP, Shlomchik MJ. A novel mouse with B cells but lacking serum antibody reveals an antibody‐independent role for B cells in murine lupus. J Exp Med 1999; 189:1639–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:563–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Teichmann LL, Cullen JL, Kashgarian M, Dong C, Craft J, Shlomchik MJ. Local triggering of the ICOS coreceptor by CD11c(+) myeloid cells drives organ inflammation in lupus. Immunity 2015; 42:552–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jacquemin C, Schmitt N, Contin‐Bordes C et al OX40 ligand contributes to human lupus pathogenesis by promoting T follicular helper response. Immunity 2015; 42:1159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sisirak V, Ganguly D, Lewis KL et al Genetic evidence for the role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med 2014; 211:1969–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rowland SL, Riggs JM, Gilfillan S et al Early, transient depletion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells ameliorates autoimmunity in a lupus model. J Exp Med 2014; 211:1977–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teichmann LL, Ols ML, Kashgarian M, Reizis B, Kaplan DH, Shlomchik MJ. Dendritic cells in lupus are not required for activation of T and B cells but promote their expansion, resulting in tissue damage. Immunity 2010; 33:967–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liao X, Reihl AM, Luo XM. Breakdown of immune tolerance in systemic lupus erythematosus by dendritic cells. J Immunol Res 2016; 2016:6269157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reilly CM, Olgun S, Goodwin D et al Interferon regulatory factor‐1 gene deletion decreases glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Eur J Immunol 2006; 36:1296–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liao X, Ren J, Wei CH et al Paradoxical effects of all‐trans‐retinoic acid on lupus‐like disease in the MRL/lpr mouse model. PLOS ONE 2015; 10:e0118176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perez de Lema G, Lucio‐Cazana FJ, Molina A et al Retinoic acid treatment protects MRL/lpr lupus mice from the development of glomerular disease. Kidney Int 2004; 66:1018–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hewicker M, Kromschroder E, Trautwein G. Detection of circulating immune complexes in MRL mice with different forms of glomerulonephritis. Z Versuchstierkd 1990; 33:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5:953–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liao X, Pirapakaran T, Luo XM. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in the development of lupus nephritis. Mediators Inflamm 2016; 2016:6012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sievers EL, Senter PD. Antibody‐drug conjugates in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Med 2013; 64:15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steinmetz OM, Turner JE, Paust HJ et al CXCR3 mediates renal Th1 and Th17 immune response in murine lupus nephritis. J Immunol 2009; 183:4693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fiore N, Castellano G, Blasi A et al Immature myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells infiltrate renal tubulointerstitium in patients with lupus nephritis. Mol Immunol 2008; 45:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Segerer S, Heller F, Lindenmeyer MT et al Compartment specific expression of dendritic cell markers in human glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2008; 74:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schiffer L, Bethunaickan R, Ramanujam M et al Activated renal macrophages are markers of disease onset and disease remission in lupus nephritis. J Immunol 2008; 180:1938–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bethunaickan R, Berthier CC, Ramanujam M et al A unique hybrid renal mononuclear phagocyte activation phenotype in murine systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis. J Immunol 2011; 186:4994–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sahu R, Bethunaickan R, Singh S, Davidson A. Structure and function of renal macrophages and dendritic cells from lupus‐prone mice. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66:1596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Celhar T, Hopkins R, Thornhill SI et al RNA sensing by conventional dendritic cells is central to the development of lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:E6195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoshimoto S, Nakatani K, Iwano M et al Elevated levels of fractalkine expression and accumulation of CD16+ monocytes in glomeruli of active lupus nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 50:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu H, Hu F, Sun X et al CD16+ monocyte subset was enriched and functionally exacerbated in driving T‐cell activation and B‐cell response in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol 2016; 7:512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamazaki T, Akiba H, Iwai H et al Expression of programmed death 1 ligands by murine T cells and APC. J Immunol 2002; 169:5538–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Inoue A, Hasegawa H, Kohno M et al Antagonist of fractalkine (CX3CL1) delays the initiation and ameliorates the progression of lupus nephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52:1522–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hochheiser K, Heuser C, Krause TA et al Exclusive CX3CR1 dependence of kidney DCs impacts glomerulonephritis progression. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:4242–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sherbenou DW, Aftab BT, Su Y et al Antibody‐drug conjugate targeting CD46 eliminates multiple myeloma cells. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:4640–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2009; 29:313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tucci M, Quatraro C, Lombardi L, Pellegrino C, Dammacco F, Silvestris F. Glomerular accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in active lupus nephritis: role of interleukin‐18. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58:251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuchen S, Robbins R, Sims GP et al Essential role of IL‐21 in B cell activation, expansion, and plasma cell generation during CD4+ T cell‐B cell collaboration. J Immunol 2007; 179:5886–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Itoh K, Hirohata S. The role of IL‐10 in human B cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation. J Immunol 1995; 154:4341–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Fig. S1. (a) Proteinuria (PU) scores of 6‐, 19‐ and 37‐week‐old Murphy Roths large (MRL) mice. ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n = 3 mice in each group. (b) Gating strategy for renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells (Lin–CD11c+CD11b+), CD11b– conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) (Lin–CD11c+CD11b–major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II+), monocytes (Lin‐CD11c‐CD11b+ lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)highSSC‐Hlow) and neutrophils (Lin–CD11c–CD11b+Ly6CmidSS‐Hhigh) as determined by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown. (c) Genotyping of wild‐type (+) and mutated (lpr) Fas gene. (d) Genotyping of wild‐type (+) and mutated [green fluorescent protein (gfp)] Cx3cr1 gene.

Fig. S2. (a) Glomerular (left) and tubulointerstitial (right) scores of antibody–drug conjugate (ADC)‐ or phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)‐treated Murphy Roths large (MRL)/lpr mice at 15 weeks old. (b) The percentages of CD44+ activated cells in splenic CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells of ADC‐ or PBS‐treated MRL/lpr mice at 15 weeks old as determined by flow cytometry. (c) Total immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgG2a levels (top row) and anti‐dsDNA IgG and IgG2a levels (bottom row) in the plasma of ADC‐ or PBS‐treated MRL/lpr mice at 15 weeks old as determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (d,e) The percentages of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II+ population (d) and the expression of CD80 and the ratio of CD86 and CD80 mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) (e) in renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, monocytes and neutrophils of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. (f) The expression of CD40, inducible co‐stimulator ligand (ICOSL) and OX40L on renal‐infiltrating CD11c+ cells, monocytes, neutrophils and CD11c–CD11b– cells (mainly lymphocytes) of 4‐month‐old MRL/lpr mice as determined by flow cytometry. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001, one‐way analysis of variance (anova). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), n ≥ 3 mice in each group.

Table S1. List of primers for reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR).

Table S2. List of primers for speed congenic polymerase chain reaction (PCR).