Summary

The pathogenesis of sepsis involves a dual inflammatory response, with a hyperinflammatory phase followed by, or in combination with, a hypoinflammatory phase. The adhesion molecules lymphocyte function‐associated antigen (LFA‐1) (CD11a/CD18) and macrophage‐1 (Mac‐1) (CD11b/CD18) support leucocyte adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecules and phagocytosis through complement opsonization, both processes relevant to the immune response during sepsis. Here, we investigate the role of soluble (s)CD18 in sepsis with emphasis on sCD18 as a mechanistic biomarker of immune reactions and outcome of sepsis. sCD18 levels were measured in 15 septic and 15 critically ill non‐septic patients. Fifteen healthy volunteers served as controls. CD18 shedding from human mononuclear cells was increased in vitro by several proinflammatory mediators relevant in sepsis. sCD18 inhibited cell adhesion to the complement fragment iC3b, which is a ligand for CD11b/CD18, also known as Mac‐1 or complement receptor 3. Serum sCD18 levels in sepsis non‐survivors displayed two distinct peaks permitting a partitioning into two groups, namely sCD18 ‘high’ and sCD18 ‘low’, with median levels of sCD18 at 2158 mU/ml [interquartile range (IQR) 2093–2811 mU/ml] and 488 mU/ml (IQR 360–617 mU/ml), respectively, at the day of intensive care unit admission. Serum sCD18 levels partitioned sepsis non‐survivors into one group of ‘high’ sCD18 and low CRP and another group with ‘low’ sCD18 and high C‐reactive protein. Together with the mechanistic data generated in vitro, we suggest the partitioning in sCD18 to reflect a compensatory anti‐inflammatory response syndrome and hyperinflammation, respectively, manifested as part of sepsis.

Keywords: adhesion molecules, complement, endotoxin shock, human, lipopolysaccharide

Introduction

Sepsis is defined by infection in combination with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Sepsis can escalate into severe sepsis and septic shock with a high mortality rate 1. The pathogenesis of sepsis is characterized by both hyperinflammation and a component of hypoimmunity. The hypoinflammatory response, originating most probably from a compensatory anti‐inflammatory response syndrome (CARS), is thought to happen almost simultaneously with the hyperinflammation. During the course of sepsis, the patient can experience both hyper‐ and hypoinflammation, with changing severity of both 2, 3, 4, 5. The hyperinflammatory component of sepsis, also termed a ‘cytokine storm’, involves up‐regulation of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α and interleukin (IL)‐1β by microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). This results in endothelial activation with up‐regulation of endothelial cellular adhesion molecules, including intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)‐1 (CD54) 6, 7, 8. Emerging studies also implicate the complement system as an important part of the inflammatory response in sepsis 9. The hypoimmune component is more subtle, and involves an increase of both T regulatory cells and myeloid‐derived suppressor cells 10, 11, 12.

CD18 forms the beta‐chain of the integrin family members lymphocyte function‐associated antigen (LFA)‐1 (also known as CD11a/CD18) and macrophage‐1 (Mac‐1) (CD11b/CD18, complement receptor 3). CD18 is found both in a surface‐bound form expressed exclusively by leucocyte cell membranes and in a shed, soluble form (sCD18) in peripheral blood and other extracellular fluids 13, 14, 15, 16. Shedding of CD18 can be induced by TNF‐α 14, 15. LFA‐1 binds ICAM‐1 as part of the process, enabling transendothelial migration of leucocytes from the circulation into the extravascular tissue contributing to inflammation and tissue damage 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Wand and Doerschuk has associated this tissue damage with LFA‐1‐dependent neutrophil migration into inflamed tissue in critical illness such as acute lung injury 21. Mac‐1 binds the complement fragments iC3b and C3d, ICAM‐1 and several other biomacromolecules 22, 23. Previously, it has been shown that sCD18, presumably in the form of sCD11a/CD18, may compete with cellular‐expressed LFA‐1 for binding to ICAM‐1 14, 16. In this way, sCD18 complexes may be an antagonist of leucocyte adhesion to inflamed tissues.

Our aim was to investigate the role of sCD18 in sepsis with emphasis on the potential use of sCD18 as a prognostic biomarker of fatal outcome of sepsis. First, we investigated the in‐vitro effects of inflammatory mediators relevant in sepsis on CD18 shedding from leucocytes and the effect of the shed sCD18 on leucocyte adhesion. Secondly, we studied alterations in sCD18 levels in a small cohort of septic and non‐septic intensive care unit (ICU) patients and analysed the potential correlations with disease outcome.

Materials and methods

Patients and healthy controls

Fifteen ICU patients with severe sepsis or septic shock and 15 non‐septic ICU patients were included from two different ICUs at Aarhus University Hospital and Randers Regional Hospital, Denmark. In addition, 15 age‐ and gender‐matched healthy controls were included 24. Exclusion criteria were patients below 18 years of age, patients who were pregnant or lactating, patients with haematocrit level below 0·25, patients who were on immune‐modulating therapy except for low‐dose steroids, patients who had received chemotherapy or radiation‐therapy within 1 year of inclusion, patients who had life‐threatening bleeding and patients who had an ICU stay shorter than 4 days. This prospective observational study was approved by the local ethics committee (The Research Ethics Committee of Central Jutland, Denmark, reg. no. M‐20080124) and the Danish data protection agency (reg. no. 2008‐41‐2421). The study was carried out in accordance with the principles in the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects, if possible, or alternatively from the closest relative and the patient's general practitioner. Severe sepsis and septic shock were classified according to the criteria given by Bone and colleagues 1. To evaluate the extent of organ dysfunction and the severity of illness, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score 25 was calculated at ICU admission and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score 26 was calculated daily during the observation period. All non‐septic patients fulfilled the SIRS criteria and had organ dysfunction in combination with an APACHE II score above 13 at admission. All ICU patients had blood samples drawn at day 1 of admission to the ICU as well as on days 2, 3 and 4. The primary site of infection was the lungs (10 of 15), followed by the abdomen (five of 15). For in‐vitro experiments, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from six healthy donor buffy coats. All samples from healthy controls were obtained from the blood bank, Department of Clinical Immunology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark. Clinical data and treatment of patients and healthy controls can be found in Table 1 and Supporting information, Table S1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

|

Sepsis (n = 15) |

Non‐sepsis (n = 15) |

HCs (n = 15) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All (n = 15) |

Survivors (n = 6) |

Non‐survivors (n = 9) |

||||||

|

All (n = 9) |

High sCD18 (n = 6) |

Low sCD18 (n = 3) |

||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 66 (62–79) | 67 (66–69) | 64 (62–79) | 54 (41–64) | 78 (62–82) | 58 (47–68) | 61 (59–63) | |

| Female gender, n (%) | 7 (47) | 4 (67) | 3 (33) | 1 (33) | 2 (33) | 8 (53) | 9 (60) | |

| Severity of disease, median (IQR) | ||||||||

| APACHE II score | 17 (15–22) | 17 (10–22) | 18 (16–20) | 20 (19–31) | 16 (15–18) | 18 (15–23) | – | |

| SOFA score | 8 (7–12) | 8 (2–10) | 8 (7–16) | 17 (16–18) | 8 (7–8) | 8 (6–11) | – | |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||||||

| Respirator/NIV | 12 (80) | 5 (83) | 7 (78) | 3 (100) | 4 (67) | 11 (73) | 0 (0) | |

| Glucocorticoids | 8 (53) | 3 (50) | 5 (56) | 2 (67) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Dialysis | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Inotropes | Nihil | 4 (27) | 2 (33) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 5 (33) | 15 (100) |

| 1 agent | 4 (27) | 2 (33) | 2 (22) | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 10 (67) | 0 (0) | |

| > 1 agent | 6 (40) | 2 (33) | 4 (44) | 1 (33) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| > 2 agents | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Antibiotics | Nihil | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (67) | 15 (100) |

| Monotherapy | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 17 (1) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Polytherapy | 14 (93) | 6 (100) | 8 (89) | 3 (100) | 5 (83) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | |

HCs = healthy controls; SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; IQR = interquartile range; NIV = non‐invasive ventilation.

Sample handling

Samples for sCD18 analysis were drawn in tubes without anti‐coagulant and centrifuged for 10 min, 1750 × g, at 4°C. Serum was removed and stored at −80 until analysis.

Stimulation of healthy control PBMCs

For in‐vitro culture experiments with PBMCs, the cells were thawed and cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin and glutamine, as performed previously 27. The cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml and incubated with phorbol‐12‐myristate‐13‐acetate (PMA) at 100 ng/ml (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 100 ng/ml (Sigma‐Aldrich), TNF‐α at 40 ng/ml (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), IL‐1β at 40 ng/ml (Peprotech), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) at 10 ng/ml (Sigma‐Aldrich) and hydrocortisone (HCT) 1000 ng/ml or 10 ng/ml (Solu‐Cortef Pfizer, New York, NY, USA). For each type of experiment, a control cell culture with the same cells in medium without addition of stimulants was used for comparison. In all experiments, cells were cultured for 48 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator 5% (v/v) CO2 without changing the medium. After incubation, supernatants were stored frozen at −80°C for later sCD18 analysis with time‐resolved immunofluorometric assay (TRIFMA).

Electric cell‐substrate impedance sensing serum inhibition assay

K562 and Mac‐1 over‐expressing K562 (Mac‐1/K562) cells were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 292 µg/ml L‐glutamine, while Mac‐1/K562 cell culture was also supplemented with 4 µg/ml puromycin. C3d was purified as described previously 22. Four mg/ml DSP (dithiobis succinimidyl propionate) was applied to E‐plate L8 chamber (ACEA, San Diego, CA, USA) with 100 µl per well. After 30 min of activation, DSP was removed and the wells were washed twice quickly by ddH2O; 10 µg/ml C3d, 100 µl per well, was added to the wells immediately and coated for 1 h. The wells were then washed three times by phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), pH 7·4, and then three times by binding buffer [10 mM HEPES, pH 7·4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1·8 mM CaCl2, supplemented with 0·1 mg/ml human serum albumin (HSA) and 5 mM d‐glucose]. The Electric Cell‐substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) cell serum inhibition assay was modified from the manufacturer's instructions. K562 and Mac‐1/K562 cells were washed once and resuspended in binding buffer. KIM‐185 antibody was added to all samples to a final concentration of 10 µg/ml, to stimulate Mac‐1. Serum and/or binding buffer were added to the cell suspension according to the required serum percentages, making a final concentration of 3 × 105 cells/ml and 0·5 ml cell suspensions, respectively, for each treatment. After well mixed, the mixtures were transferred to E‐plate L8. Data collection was performed with iCELLigence equipment (ACEA) for 8 h with incubation at 37°C, supplemented with 5% (v/v) CO2. Experiments were repeated at least three times.

Quantification of sCD18 by time‐resolved immunofluorometric assays

Levels of sCD18 were measured using TRIFMA, as described previously 14, 16. Briefly, microtitre wells were coated with 1 μg/ml of mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 anti‐CD18 antibody (KIM18; GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) or, as control, mouse IgG1 isotype in PBS and blocked with 1 mg/ml HSA in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS). Serum samples diluted 1/10 in TBS/Tween with 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 100 μg/ml aggregated human Ig (Beriglobin; ZLB Behring, King of Prussia, PA, USA) were added to the wells, and the plates incubated overnight at 4°C. The wells were incubated with 1 μg/ml biotinylated mouse IgG1 anti‐CD18 antibody (KIM127; GenScript) in TBS/Tween with 100 μg/ml aggregated bovine IgG (Lampire Biological Laboratories, Everett, PA, USA) to block possible interference by heterophilic antibodies 28. Eu3+‐conjugated streptavidin was applied and the signals read by time‐resolved fluorometry. Signals were compared against a standard curve made from titrations of healthy control plasma defined to contain 1000 mU/ml.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were described by the median and interquartile range (IQR). Cell culture experiments were analysed with the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. The iCELLigence adhesion assay data was analysed as log‐transformed ratios with the paired t‐test. Comparisons of the plasma sCD18 levels between groups were made using the t‐test on log‐transformed data. Comparisons of clinical disease activity scores and test results between groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U‐test. For correlation analysis, Pearson's r coefficient was calculated with a two‐tailed P‐value. For all experiments, significant values had a P‐value < 0·5 (*) or P‐value < 0·005 (**). Calculations and graphs were using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

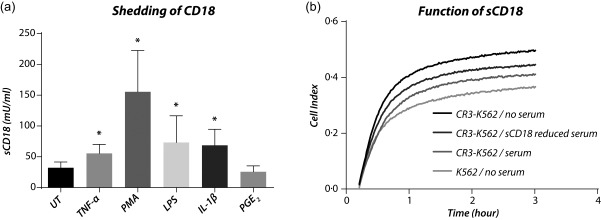

In‐vitro inflammatory induction of CD18 shedding

To elucidate some of the mechanisms affecting the concentration of sCD18, the effect of different inflammatory mediators on shedding of CD18 from PBMCs from healthy controls was investigated. Stimulation with TNF‐α was used as a positive control. The concentration of sCD18 was increased in supernatants from cells incubated with TNF‐α, PMA, LPS and IL‐1β compared with untreated cells (all P < 0·05) (Fig. 1a). The concentration of sCD18 was not changed in supernatants from cells incubated with PGE2 (P = 0·16) (Fig. 1a). This indicates that several inflammatory molecules can increase the shedding of CD18 from cells in the peripheral blood. As several of the patients were treated with HCT during their ICU stay, an in‐vitro study measuring the effect of HCT on shedding of sCD18 was also conducted (Supporting information, Fig S1). There seemed to be a tendency that HCT had a decreasing effect on the shedding of CD18, but the concentration from 0·01 µg/ml and 1·00 µg/ml was not significantly different from the baseline (P = 0·31 and P = 0·06, respectively).

Figure 1.

In‐vitro shedding of CD18 and function of sCD18. (a) Inflammatory induction of CD18 shedding. The levels of sCD18 were increased in the supernatants from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) incubated with tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, phorbol‐12‐myristate‐13‐acetate (PMA), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interleukin (IL)‐1β and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Lines indicate median and whiskers indicate interquartile range (IQR). Data were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. (b) Antagonistic function of sCD18. Depletion of sCD18 in healthy volunteer serum resulted in increased Mac‐1‐mediated cell adhesion. *P < 0·05.

In‐vitro antagonistic effects of sCD18

Next, the function of sCD18 was studied using sCD18‐reduced serum applied in a cell adhesion assay. We used a cell adhesion assay measuring binding of Mac‐1‐expressing K562 cells to C3d. K562 cells not expressing Mac‐1 were used as a negative control (Fig. 1b). The sCD18‐reduced serum was made by incubating heat‐inactivated serum from a healthy control in sterile wells coated with anti‐CD18 antibody. IgG1 isotype antibody‐coated wells were used to prepare a control serum. The concentration of sCD18 was 314 mU/ml in serum incubated with anti‐CD18 antibody and 936 mU/ml in serum from IgG1 isotype antibody‐coated wells. The concentration of sCD18 was 314 mU/ml in serum depleted with anti‐CD18 antibody and 936 mU/ml in serum treated in IgG1 isotype antibody‐coated wells. The binding of Mac‐1 expressing cells to C3d was increased when adding the sCD18 reduced serum compared with control serum (P = 0·036) (Fig. 1b).

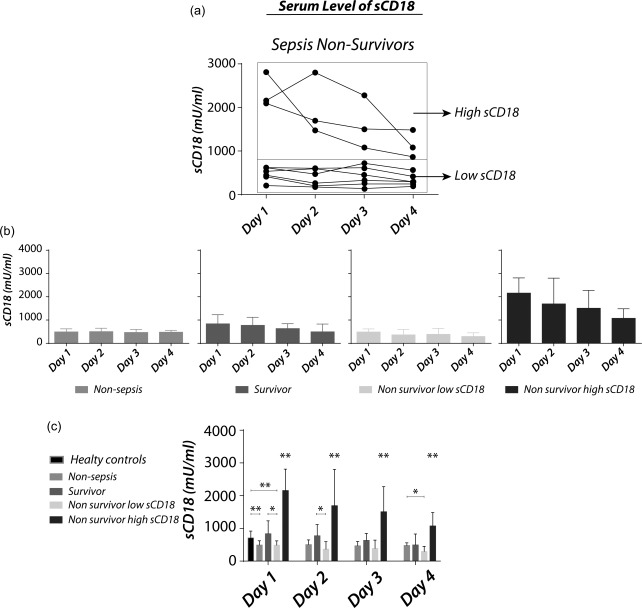

Partitioning of sCD18 levels into two distinct populations

Levels of sCD18 were not altered significantly in sepsis non‐survivors compared with sepsis survivors or healthy controls. However, sCD18 levels displayed two distinct peaks in the sepsis non‐survivors, which were partitioned essentially into two groups; the sCD18 ‘high’ group with a median concentration of 2158 mU/ml (IQR 2093–2811 mU/ml) and in the sCD18 ‘low’ group with a median concentration of 488 mU/ml (IQR 360–617 mU/ml) at day 1 (Fig. 2a). The levels of sCD18 were increased in ‘high’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors compared with all other groups (P < 0·005) and decreased in ‘low’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors compared with sepsis survivors on days 1 and 2 (P < 0·05) and healthy controls (P < 0·005) (Fig. 2c). The non‐sepsis patients had decreased amounts of sCD18 compared with healthy controls (P < 0·005) (Fig. 2c). No differences in levels of sCD18 were observed between sepsis survivors and healthy controls (P > 0·55) (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Serum levels of sCD18 in sepsis patients, non‐sepsis intensive care unit (ICU) patients and healthy controls. (a) Partitioning of serum levels of sCD18 in sepsis non‐survivors into ‘sepsis non‐survivor low sCD18’ and ‘sepsis non‐survivor high sCD18’. (b) Serum levels of sCD18 in non‐sepsis ICU patients, sepsis survivors, sepsis non‐survivors sCD18 low and sepsis non‐survivors’ high sCD18. (c) The levels of sCD18 were increased in the high sCD18 sepsis non‐survivor group and decreased in the low sCD18 sepsis non‐survivor group compared with sepsis survivors and healthy controls. Bars indicate median and whiskers indicate IQR. Data were analysed using Student's t‐test on log‐transformed data. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

Association of sCD18 with paraclinical variables

The ‘high’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors had decreased concentrations of C‐reactive protein (CRP) and increased SOFA scores compared with both the ‘low’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors (P < 0·05) and sepsis survivors (P < 0·05) (Fig. 3a,b). The differences in leucocyte count and APACHE score were not significant. There were no differences between the ‘low’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors and sepsis survivors. Our data suggest that the sepsis non‐survivors can be partitioned into two distinct populations with either (1) ‘high’ sCD18 and low CRP or (2) ‘low’ sCD18 and high CRP. We observed a tendency towards a negative correlation between sCD18 and CRP as well as between sCD18 and leucocyte count, P = 0·0041 and P = 0·0084, respectively (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

The sCD18 serum concentration and sepsis severity. (a) Sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) in non‐sepsis intensive care unit (ICU) patients, sepsis survivors and sepsis non‐survivors partitioned according to high and low sCD18 levels. Sepsis non‐survivors’ high sCD18 have a significantly increased SOFA score compared to all other groups, P < 0·005. (b) Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE) in non‐sepsis ICU patients, sepsis survivors and sepsis non‐survivors partitioned according to high and low sCD18 levels. All groups except healthy controls had APACHE II scores above 13. (c) C‐reactive protein (CRP) in healthy controls, non‐sepsis ICU patients, sepsis survivors and sepsis non‐survivors partitioned according to high and low sCD18 levels. Sepsis non‐survivors’ high sCD18 had decreased levels of CRP that were significantly lower on days 1 and 2, but stabilized on days 3 and 4 as sCD18 levels decreased. (d) Leucocyte count in healthy controls, non‐sepsis ICU patients, sepsis survivors and sepsis non‐survivors partitioned according to high and low sCD18 levels. (e) Correlation between sCD18 level and CRP. Pearson's r‐value and P‐value indicated in upper right corner. (f) Correlation between leucocyte count and sCD18 level. Pearson's r‐value and P‐value indicated in upper right corner. Bars indicate median and whiskers indicate interquartile range (IQR). Data were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U‐ test. Pearson's r‐value correlations were calculated using a two‐tailed P‐value. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of sepsis is hypothesized to involve both hyperinflammation with up‐regulation of proinflammatory cytokines and a component of hypoimmunity 2. The partitioning of patients with a fatal outcome of sepsis in ‘sCD18 high’ and ‘sCD18 low’ in this study now supports this hypothesis.

We have shown increased CD18 shedding previously in response to TNF‐α stimulation 14, 15. Here, we found increased CD18 shedding in response to several inflammatory mediators relevant in sepsis, indicating that CD18 shedding is the result of many inflammatory pathways. Previously, sCD18 was shown to bind ICAM‐1 coated on plastic surfaces or expressed in cell membranes 14, 16. Furthermore, sCD18 may act as an antagonist to cell‐expressed LFA‐1 binding of ICAM‐1 14. In the present study, we observed that the influence of sCD18 could be extended to other CD18 integrin ligands, i.e. C3d, which is a well‐characterized ligand for Mac‐1 22. Compared with sCD18‐depleted serum, full serum was shown to attenuate the adhesion of Mac‐1 expressing cells to C3d. This finding is remarkable, as attempts to quantify the amount of Mac‐1 in human plasma has been limited by the only low, albeit detectable, CD11b signals developed in our assays 14. By contrast, soluble Mac‐1 is detected readily in murine serum 29. The observations made in the present study now point to sCD18 complexes capable of modulating Mac‐1 binding to complement. This adds to the hypothesis that sCD18 functions as a natural anti‐inflammatory molecule broadly modulating CD18 integrin functions, also in line with earlier suggestions that soluble CD18 integrins could serve as anti‐inflammatory agents useful in therapy 30, 31.

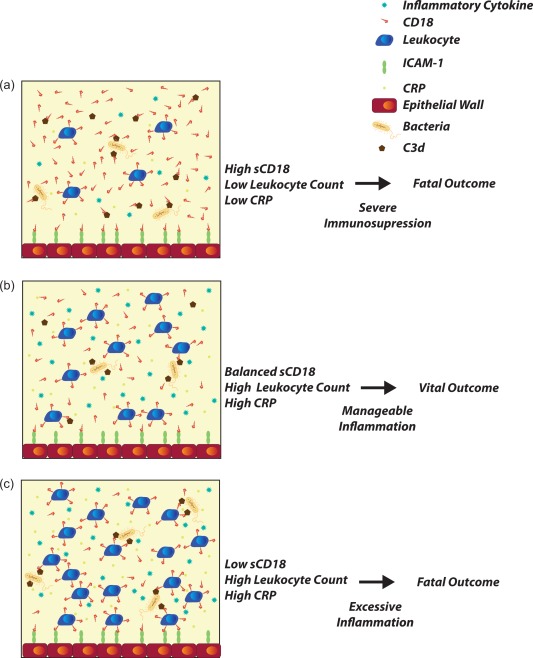

One possible contribution to this observation is the complex equilibrium between shedding of CD18 and depletion of sCD18 to ligand‐coated surfaces such as activated endothelium and complement‐conjugated microbial particles 32. In addition, correlational studies of the leucocyte count compared with the level of sCD18 showed that a low leucocyte count could be associated with high levels of sCD18. Based on preliminary data not shown here, we have constructed a model for shedding of CD18 that involves the transmigration of leucocytes through the endothelial wall when shedding CD18 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Shedding of sCD18 associated with leucocyte migration into tissue and release of cytokines. (a) Leucocytes have migrated across the endothelial barrier in high numbers and, as a result, large amounts of CD18 are shed from the membrane to enable transmigration. Leucocytes will then cause tissue damage and release vast amounts of cytokines inside the tissue increasing inflammation. Correspondingly, the level of C‐reactive protein (CRP) in plasma is low and the leucocyte count is low. This causes immunosuppression in blood and increases the risk of secondary opportunistic infections. Due to excessive tissue damage and organ failure the outcome is fatal. (b) The amount of leucocytes migrated into tissue is lower and, as a result, sCD18 levels are balanced. Inflammation in tissue is manageable and the patient is not subject to severe immunosuppression. In addition, the CRP level is high, decreasing the risk of secondary infections. This scenario has a vital outcome. (c) Amount of leucocytes in the blood is very high and sCD18 level is low. Few leucocytes have migrated across the endothelial barrier causing low tissue damage. However, the inflammation in blood is high, causing a risk of anaphylaxis and drop in blood pressure. sCD18 in blood is also too low to bind complements and limit the release of anaphylatoxins. This leaves a fatal outcome for the patient. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The concentration of sCD18 in serum is the result of a balance between shedding of CD18 from the surface of leucocytes and depletion through the binding of sCD18 to receptors such as ICAM‐1 expressed on cellular surfaces 14, 16. The findings reported here suggest that high serum sCD18 concentrations could reflect an overweight of CARS (hypoinflammation), while low serum sCD18 concentrations reflect increased binding to up‐regulated ligands (hyperinflammation). Supporting this notion, the ‘high’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors also had low CRP, while the ‘low’ sCD18 sepsis non‐survivors had high CRP. This is in line with previous studies showing that some septic patients have a rapid production of proinflammatory cytokines while other patients have a predominance of anti‐inflammatory cytokines or a depressed cytokine production 2, 3, 4. In arthritis, anecdotal evidence from four patients showed a similar inverse relation between the plasma CRP and sCD18 levels 14. In this way, sCD18 and CRP levels may follow similar patterns shared between different inflammatory diseases, probably reflecting the central role of at least CD18 integrins in development of the inflammatory response.

The finding of a population of sepsis non‐survivors showing immunosuppression is of potential clinical interest. At least in principle, these patients could benefit from immunoadjuvant therapy 33 to limit secondary opportunistic infections seen regularly in patients with severe sepsis 34. However, we acknowledge that the outcome of such therapy remains speculative and requires a more detailed analysis, both in terms of defining immunomodulatory targets as well as clinical investigations.

In clinical practice, the diagnosis and management of sepsis poses a substantial challenge in the treatment of critically ill patients, with considerable consequences concerning adequate antibiotic therapy, immune modulation and fluid resuscitation. As a result, there is an unmet need for diagnostic and prognostic markers to diagnose and predict sepsis severity and outcome 35. CRP has been used extensively due to its availability, low cost and limited time consumption and increased levels of CRP in sepsis patients have been shown numerous times 36, 37, 38, 39, 40. However, its use as a diagnostic biomarker is not well supported 41, 42, 43. Many other biomarkers evaluating sepsis have been evaluated with varying specificity and sensitivity, such as IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐10 and IL‐12, sCD163, sIL‐2R, sTNF‐R and others 44. We propose that sCD18 could be included in a panel of sepsis biomarkers, increasing the overall sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis and evaluation of severity. This situation clearly calls for extended investigations to evaluate the usage of defined molecular markers. While we wish to associate the efforts in the present paper with this need, at least four limitations in the study should be considered. First, a sample size of 15 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock warrants, of course, confirmation in larger trials. Secondly, albeit accompanying in‐vitro experiments form a mechanistic link between formation of sCD18 and sepsis, the clinical part of our study was basically observational. In consequence, causes and effects are poorly resolved. Thirdly, the onset of disease was unknown in the septic group of patients, potentially obscuring comparisons, especially when considering that the level of sCD18 seems to stabilize during inflammatory disease 15. Fourthly and finally, immunosuppression with steroid therapy may have influenced our results, although patients who received high‐dose glucocorticoid treatment were excluded prior to the study.

Based on the in‐vitro experiments exploring the effects of steroids on the shedding of CD18 there seemed to be a decrease, although not significant, of shedding associated with the treatment of steroids. However, as the patients receiving steroid therapy was distributed evenly among all sepsis groups including the sCD18 high group, as shown in Table 1, the effect did not seem to influence the overall tendency of the data.

In conclusion, serum levels of anti‐inflammatory sCD18 partitioned sepsis non‐survivors in two groups: one with ‘high’ sCD18 and low CRP and another with ‘low’ sCD18 and high CRP. This could reflect CARS and hyperinflammation, respectively. Nevertheless, an obvious drawback for using sCD18 as a biomarker in sepsis is the overlap between patients both with and without sepsis and healthy controls. As noted above, possible improvements may involve stratification of the patients under investigation by combining data from several established biomarkers with the new potentials of sCD18.

Disclosure

The authors declare no financial or non‐financial conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Table S1. Clinical data on sepsis patients.

Fig. S1. In‐vitro shedding of CD18 in response to steroid treatment. The levels of sCD18 were decreased in the supernatants from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) incubated with Solu‐Cortef in a dose‐dependent manner. Lines indicate the median and whiskers indicate interquartile range (IQR). Data were analysed using Wilcoxon's signed‐rank test. The treatment group was not statistically significantly different from the control group.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bettina Grumsen (Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University) for excellent technical assistance. We also acknowledge laoratory technician Lene Vestergaard for excellent technical assistance. We thank professor Else Tønnesen as well as Head‐of‐Department Hans Skriver Jørgensen and Lisbeth Kidmose for their participation.The work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Danish Council for Independent Research Medical Sciences (09‐065582), the A. P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, The Holger and Ruth Hesses Memorial Foundation, Managing Director Jacob Madsen and wife Olga Madsens Foundation, the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation and the Danish Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicines Foundation.

Contributor Information

T. W. Kragstrup, Email: kragstrup@biomed.au.dk.

T. Vorup‐Jensen, Email: vorup-jensen@biomed.au.dk.

References

- 1. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB et al Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992; 101:1644–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tang BM, Huang SJ, McLean AS. Genome‐wide transcription profiling of human sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care 2010; 14:R237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boomer JS, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. The changing immune system in sepsis: is individualized immuno‐modulatory therapy the answer? Virulence 2014; 5:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patil NK, Bohannon JK, Sherwood ER. Immunotherapy: a promising approach to reverse sepsis‐induced immunosuppression. Pharmacol Res 2016; 111:688–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shapiro NI, Schuetz P, Yano K et al The association of endothelial cell signaling, severity of illness, and organ dysfunction in sepsis. Crit Care 2010; 14:R182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aird WC. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 2003; 101:3765–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reinhart K, Bayer O, Brunkhorst F, Meisner M. Markers of endothelial damage in organ dysfunction and sepsis. Crit Care Med 2002; 30:S302–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ward PA. In sepsis, complement is alive and well. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:1026–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Venet F, Chung CS, Monneret G et al Regulatory T cell populations in sepsis and trauma. J Leukoc Biol 2008; 83:523–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delano MJ, Scumpia PO, Weinstein JS et al MyD88‐dependent expansion of an immature GR‐1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1463–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Segre E, Fullerton JN. Stimulated whole blood cytokine release as a biomarker of immunosuppression in the critically ill: the need for a standardized methodology. Shock 2016; 45:490–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Evans BJ, McDowall A, Taylor PC, Hogg N, Haskard DO, Landis RC. Shedding of lymphocyte function‐associated antigen‐1 (LFA‐1) in a human inflammatory response. Blood 2006; 107:3593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gjelstrup LC, Boesen T, Kragstrup TW et al Shedding of large functionally active CD11/CD18 Integrin complexes from leukocyte membranes during synovial inflammation distinguishes three types of arthritis through differential epitope exposure. J Immunol 2010; 185:4154–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kragstrup TW, Jalilian B, Keller KK et al Changes in soluble CD18 in murine autoimmune arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis reflect disease establishment and treatment response. PLOS ONE 2016; 11:e0148486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kragstrup TW, Jalilian B, Hvid M et al Decreased plasma levels of soluble CD18 link leukocyte infiltration with disease activity in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16:R42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marlin SD, Springer TA. Purified intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1) is a ligand for lymphocyte function‐associated antigen 1 (LFA‐1). Cell 1987; 51:813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Millan J, Williams L, Ridley AJ. An in vitro model to study the role of endothelial rho GTPases during leukocyte transendothelial migration. Methods Enzymol 2006; 406:643–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peters K, Unger RE, Brunner J, Kirkpatrick CJ. Molecular basis of endothelial dysfunction in sepsis. Cardiovasc Res 2003; 60:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell 1994; 76:301–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Q, Doerschuk CM. The signaling pathways induced by neutrophil‐endothelial cell adhesion. Antioxid Redox Signal 2002; 4:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bajic G, Yatime L, Sim RB, Vorup‐Jensen T, Andersen GR. Structural insight on the recognition of surface‐bound opsonins by the integrin I domain of complement receptor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:16426–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vorup‐Jensen T. On the roles of polyvalent binding in immune recognition: perspectives in the nanoscience of immunology and the immune response to nanomedicines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012; 64:1759–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kjaergaard AG, Dige A, Nielsen JS, Tonnesen E, Krog J. The use of the soluble adhesion molecules sE‐selectin, sICAM‐1, sVCAM‐1, sPECAM‐1 and their ligands CD11a and CD49d as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in septic and critically ill non‐septic ICU patients. APMIS 2016; 124:846–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985; 13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J et al The SOFA (Sepsis‐related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis‐related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996; 22:707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kragstrup TW, Andersen T, Holm C et al Toll‐like receptor 2 and 4 induced interleukin‐19 dampens immune reactions and associates inversely with spondyloarthritis disease activity. Clin Exp Immunol 2015; 180:233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kragstrup TW, Vorup‐Jensen T, Deleuran B, Hvid M. A simple set of validation steps identifies and removes false results in a sandwich enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay caused by anti‐animal IgG antibodies in plasma from arthritis patients. Springerplus 2013; 2:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nielsen GK, Vorup‐Jensen T. Detection of soluble CR3 (CD11b/CD18) by time‐resolved immunofluorometry. Methods Mol Biol 2014; 1100:355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dana N, Fathallah DM, Arnaout MA. Expression of a soluble and functional form of the human beta 2 integrin CD11b/CD18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991; 88:3106–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zerria K, Jerbi E, Hammami S et al Recombinant integrin CD11b A‐domain blocks polymorphonuclear cells recruitment and protects against skeletal muscle inflammatory injury in the rat. Immunology 2006; 119:431–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen MB, Zhou X, Larsen EK et al Curvature of synthetic and natural surfaces is an important target feature in classical pathway complement activation. J Immunol 2010; 184:1931–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shindo Y, Unsinger J, Burnham CA, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Interleukin‐7 and anti‐programmed cell death 1 antibody have differing effects to reverse sepsis‐induced immunosuppression. Shock 2015; 43:334–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sundar KM, Sires M. Sepsis induced immunosuppression: implications for secondary infections and complications. Indian J Crit Care Med 2013; 17:162–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pierrakos C, Vincent JL. Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care 2010; 14:R15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matson A, Soni N, Sheldon J. C‐reactive protein as a diagnostic test of sepsis in the critically ill. Anaesth Intensive Care 1991; 19:182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yentis SM, Soni N, Sheldon J. C‐reactive protein as an indicator of resolution of sepsis in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 1995; 21:602–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Povoa P, Almeida E, Moreira P et al C‐reactive protein as an indicator of sepsis. Intensive Care Med 1998; 24:1052–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Povoa P, Coelho L, Almeida E et al C‐reactive protein as a marker of infection in critically ill patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005; 11:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Castelli GP, Pognani C, Meisner M, Stuani A, Bellomi D, Sgarbi L. Procalcitonin and C‐reactive protein during systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis and organ dysfunction. Crit Care 2004; 8:R234–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clec'h C, Ferriere F, Karoubi P et al Diagnostic and prognostic value of procalcitonin in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:1166–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brunkhorst FM, Eberhard OK, Brunkhorst R. Discrimination of infectious and noninfectious causes of early acute respiratory distress syndrome by procalcitonin. Crit Care Med 1999; 27:2172–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Luzzani A, Polati E, Dorizzi R, Rungatscher A, Pavan R, Merlini A. Comparison of procalcitonin and C‐reactive protein as markers of sepsis. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:1737–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ventetuolo CE, Levy MM. Biomarkers: diagnosis and risk assessment in sepsis. Clin Chest Med 2008; 29:591–603, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Table S1. Clinical data on sepsis patients.

Fig. S1. In‐vitro shedding of CD18 in response to steroid treatment. The levels of sCD18 were decreased in the supernatants from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) incubated with Solu‐Cortef in a dose‐dependent manner. Lines indicate the median and whiskers indicate interquartile range (IQR). Data were analysed using Wilcoxon's signed‐rank test. The treatment group was not statistically significantly different from the control group.