Summary

Toll‐like receptors (TLRs) are germline‐encoded, non‐clonal innate immune receptors, which are often the first receptors to recognize the molecular patterns on pathogens. Therefore, the immune response initiated by TLRs has far‐reaching consequences on the outcome of an infection. As soon as the cell surface TLRs and other receptors recognize a pathogen, the pathogen is phagocytosed. Inclusion of TLRs in the phagosome results in quicker phagosomal maturation and stronger adaptive immune response, as TLRs influence co‐stimulatory molecule expression and determinant selection by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and MHC class I for cross‐presentation. The signals delivered by the TCR–peptide–MHC complex and co‐stimulatory molecules are indispensable for optimal T cell activation. In addition, the cytokines induced by TLRs can skew the differentiation of activated T cells to different effector T cell subsets. However, the potential of TLRs to influence adaptive immune response into different patterns is severely restricted by multiple factors: gross specificity for the molecular patterns, lack of receptor rearrangements, sharing of limited number of adaptors that assemble signalling complexes and redundancy in ligand recognition. These features of apparent redundancy and regulation in the functioning of TLRs characterize them as important and probable contributory factors in the resistance or susceptibility to an infection.

Keywords: Leishmania, Macrophage, Pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMP), Phagolysosome, Toll‐like Receptors (TLRs)

Introduction

‘Das war ja toll’ (‘That's something fantastic!’) is how Christiane Nusslein‐Volhard expressed the significance of Toll in Drosophila in 1985. The protein encoded by the Toll gene was implicated in preserving the dorsoventral patterning in developing Drosophila embryos 1. A decade later, Hoffmann and Lemaitré laid the foundation of immunodefensive properties of Toll against fungal infection in Drosophila and revealed that Toll‐like receptors (TLRs) trigger a specific response for different microbes resulting in activation of distinct regulatory pathways 2, 3. This landmark discovery was followed by the description of the human homologue of Toll – the hToll that was later renamed as TLR‐4 – which was shown to play a similar immunodefensive role against Gram‐negative bacteria‐expressed lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in human 4. Corroborative to this finding, TLR‐4‐deficient mice were resistant to LPS‐induced shock 5. Positional cloning identified a tlr4 gene mutation that renders it non‐functional in recognizing LPS, validating that TLR‐4 serves as a natural receptor for LPS 6, 7. Consequently, prediction of the number of innate immune receptors reaching asymptotes began to show the first evidence 8. These receptors – the TLRs – were characterized as the germline‐encoded transmembrane spanning receptors that recognize invariant patterns associated with the pathogen‐expressed molecules 9. TLRs remain evolutionarily conserved, as they are comprised of an ectodomain having a solenoid horseshoe‐shaped binding motif with leucine‐rich repeats [LRR, that serves as a platform for different pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP) insertions] and a cytoplasmic domain homologous to interleukin (IL)‐1 receptor labelled as the Toll/IL‐1R homology (TIR) domain 10. TLR ligands are the conserved molecular products associated with parasites, fungi, viruses and bacteria – both Gram‐positive and ‐negative 11. TLRs are now known to recognize the Danger‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from apoptotic cells and necrotic cells 12. Thus, TLRs evolved as the sensors for the innate immune system across invertebrate and vertebrate animals with a potential for recognizing virtually all pathogenic signatures from diverse microorganisms. IL‐1R, Toll dorsal pathway and TLR are known to culminate in nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF)‐κB and transcriptional activation of the genes for inflammatory cytokines 13.

Toll‐like receptors and pathogen recognition

To date, 13 TLRs have been described in mammals. Ten TLRs are expressed in humans and 12 are expressed in mice. TLR‐10 is not expressed in mice, whereas TLR‐11, TLR‐12 and TLR‐13 are not expressed in humans. Of these TLRs, TLR‐1, TLR‐2, TLR‐4, TLR‐5, TLR‐6, TLR‐10, TLR‐11 and TLR‐12 are expressed on cell membrane, whereas TLR‐3, TLR‐7, TLR‐8, TLR‐9 and TLR‐13 are expressed intracellularly on endosomal membrane. Corroborating this localization, the cell surface TLRs bind the ligands expressed on the surface of pathogens. Once internalized, the pathogen is degraded releasing their nucleic acids. Therefore, the intracellular TLRs recognize the pathogen‐derived nucleic acids as their ligands.

Irrespective of their locations, the ligand binding domain of all TLRs is comprised of leucine‐rich repeats 10. The number of amino acids in each repeat and the number of repeats determine the versatility and their restricted ligand specificity. Because these receptors are germline‐encoded and do not undergo any recombination, the fine antigen specificity, as displayed by the antigen receptors on B cells and T cells, is lacking. Therefore, in order to accommodate the huge number of pathogenic signatures, TLRs adopt several strategies to protect a given species. First, antigenic specificity is restricted to gross patterns, not to very specific sequences of amino acids in a protein or sugar residues in a glycan or unsaturation in lipids or even small side groups in these molecules. Therefore, these receptors, along with some other innate immune receptors, are termed pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Secondly, the population studies revealed polymorphism in TLRs. The TLR‐2 and TLR‐4 polymorphisms affecting the susceptibility to pathogens and immune response 14 imply that most variations in the PAMPs are recognized by host cells restricting the immune evasion by the pathogen. Thirdly, the TLRs can heterodimerize to increase the breadth of the antigens recognized. The most versatile is TLR‐2, which binds to either TLR‐1 or TLR‐6 in mice or TLR‐10 in humans 15. The TLR‐1–TLR‐2 heterodimer recognizes triacylated peptides, whereas TLR‐2–TLR‐6 recognizes diacylated peptides 16, 17. Such dimerization has not been reported for intracellular TLRs, due perhaps to fewer variations in the patterns formed by DNA and RNA. Fourthly, dimerization through their intracytoplasmic domains alter the adaptor‐binding platforms and, as a result, the TLRs working as a monomer vis‐à‐vis a dimer use different adaptors and trigger different signalling pathways 18, 19. Finally, the phagosomal maturation may affect the subsequent cellular responsiveness that includes antigen processing, antigenic determinant selection, co‐stimulatory molecule expression and cytokine production (Fig. 1). The immune response is thus dependent upon the mode of phagosomal maturation 20. Because inclusion of TLR‐2 in the phagosome enhances its maturation, it is believed that TLR‐regulated phagosomal maturation may also play a role in the regulation of immune response against a pathogen, in particular the intracellular pathogens such as Leishmania.

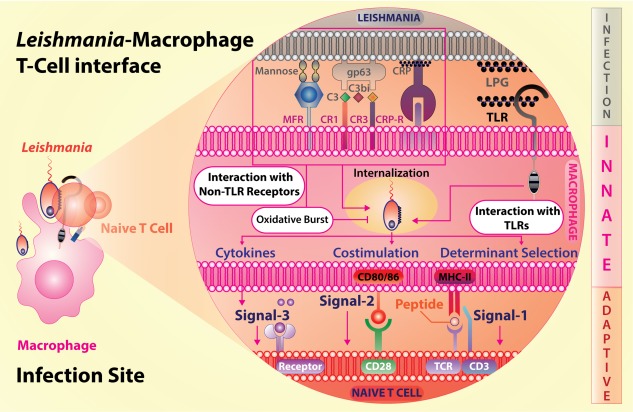

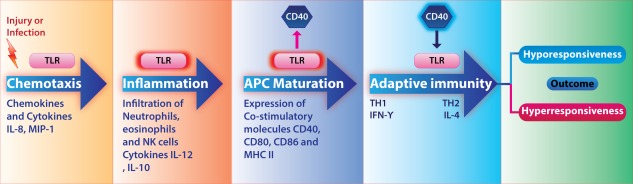

Figure 1.

Leishmania interacts with macrophages via Toll‐like receptors (TLRs) and non‐TLRs following the initial interaction and internalization, three signals, through T cell receptor–peptide antigen–major histocompatibility complex (TCR‐Ag‐MHC), co‐stimulatory molecules and cytokines, are generated by macrophages to activate naive T cells and subsequent production of their effector cytokines.

Leishmania – a protozoan parasite – causes leishmaniasis

Leishmania–TLR interactions reflect an important aspect of the modus operandi of the immune system. Immune homeostasis is maintained by a delicate balance between proinflammatory and anti‐inflammatory responses. An exaggerated inflammation can lead to hypersensitivity, and even autoimmunity, whereas a subdued response may contribute to susceptibility to infections. TLRs play dual roles in this operational set‐up of the immune system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Leishmania and Toll‐like receptor (TLR) immune response paradigm in experimental infection

| Leishmania species and distribution | Disease | Organs involved | TLRs involved | Comment in context of immune response | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus – Leishmania (Ross 1903) | |||||

| L. donovani (East Africa, Indian sub‐continent) | VL/PKDL | Spleen, liver, BM | TLR‐2, TLR‐4, TLR‐3, TLR‐7, TLR‐9 | TLR‐2 modulates MAPK pathway | 21 |

| IL‐12, TNF‐α suppression via NF‐κB | 22 | ||||

| Endosomal TLR‐s activate B cells in L. donovani infection | 23 | ||||

| L. infantum/chagasi (Africa, Asia, South Central, America) | VL | Spleen, liver, BM | TLR‐2, TLR‐4 | Modulation of cytokines such as TNF‐α, IL‐17, IL‐10 and TGF‐β | 24 |

| L. major (Africa and Asia) | CL | Skin, (nodules that may ulcerate) | TLR‐2, TLR‐9 | TLR‐2 suppresses TLR‐9 expression | 25 |

| L. major DNA–TLR‐9 activates DC, favouring Th1 development | 26 | ||||

| TLR‐9 offer resistance to L. major infection | 27 | ||||

| L. tropica (Europe, Asia, North Africa) | CL/DCL | Skin | TLR‐2 | LPG derived from L. tropica results in a weak induction of TLR‐2 | 27 |

| L. mexicana (Central America) | CL | Skin (nodular ulcers) | TLR‐2, TLR‐4 | NK cells in early protective responses | 28 |

| IL‐12 suppression by TLR‐4‐dependent COX‐2, arginase‐1 expression | 29 | ||||

| Transient exacerbation of the disease via promotion of Th2 response | 30 | ||||

| L. amazonensis (South America) | CL | Skin, (local nodules) | TLR‐2 | TLR‐2 deficiency reduces the infection significantly | 31 |

| L. pifanoi (South America) | CL | TLR‐4 | TLR‐4 recognition of L. pifanoi amastigotes controls infection | 32 | |

| Subgenus – Viannia (Lainson and Shaw, 1987) | |||||

| L. panamensis (Central America) | MCL/CL | OPC, nasal septum | TLR‐1, TLR‐2, TLR‐3, TLR‐4 | TLR‐4 and endosomal TLRs activate macrophages to provide early immunity | 33 |

| L. braziliensis (South America) | MCL | OPC | TLR‐2, TLR‐4, TLR‐9, | TLR‐9 offers early control of lesion development but dispensable for Th1 differentiation | 34 |

| Monocyte‐driven NO, ROS production and pathogen killing | 35 | ||||

| L. guyanensis (South America) | CL and MCL | OPC | TLR‐9 | MyD88‐ and TLR‐9‐dependent immune responses arise independently to LRV within the parasites | 36 |

BM = bone marrow; CL = cutaneous Leishmaniasis; DC = dendritic cell; DCL = diffused cutaneous Leishmaniasis; LRV = Leishmania‐resident RNA virus; MCL = muco‐cutaneous Leishmaniasis; MAPK = mitogen‐activated protein kinase; NK = natural killer; NO = nitric oxide; OPC = oro‐pharyngeal cavity; PKDL = post‐Kala‐azar dermal Leishmaniasis; ROS = reactive oxygen species; VL = visceral Leishmaniasis; NF‐κB: nuclear factor kappa B; IL = interleukin; TGF = transforming growth factor; TNF = tumour necrosis factor.

Leishmania is a dimorphic protozoan parasite that completes the life cycle in two organisms: the sandfly vector and a mammalian host, ranging from rodents and canids to humans. In the vector, the parasite remains as motile extracellular flagellated promastigotes, whereas in a mammalian host it exists as sessile aflagellate intracellular amastigotes 37. The promastigotes divide by binary fission in sandfly gut and establish themselves in the midgut of sandfly. During episodes of haematophagy, natural infection begins with the epidermal transfer of metacyclic promastigotes leading to dissemination of the infective promastigotes that are phagocytosed eventually by monocytes and infiltrating macrophages. Depending on the species of the parasite, different organs are involved leading to different forms of the disease leishmaniasis with characteristic pathophysiology. L. donovani causes visceral leishmaniasis involving spleen, liver, bone marrow and, in some cases, lymph nodes, whereas L. major causes cutaneous leishmaniasis involving skin and the local draining lymph nodes (Table 1).

Leishmaniases are prevalent in tropical, subtropical, African subcontinent and temperate regions because of the prominence of the disease carriers in these regions 38; 0·2–0·4 million cases of VL with 20 000–40000 fatalities and 0·7 to 1·2 million cases of CL are reported annually. The situation is aggravated further by the lack of non‐toxic, orally bioavailable drugs, emerging resistance against antimonials and miltefosine, co‐infection with human immunodeficiency virus, persistence of the vector and the lack of an anti‐leishmanial vaccine. The prevailing relatively inefficient anti‐leishmanial chemotherapy therefore calls for urgent immunotherapeutic and prophylactic interventions. As TLRs are the first innate receptors that recognize Leishmania, a TLR‐targeted therapy holds strong potential. Similarly, as TLR ligands enhance the immune response, they can be used as adjuvants in the prophylactic strategies. Leishmania–TLR interaction is therefore of intense interest and a focus of research. However, the regulatory roles played by TLRs, multiplicity of the receptor and apparently contradictory reports raise many questions that need to be addressed for putting TLRs to any therapeutic or prophylactic useage.

Leishmania–macrophage interaction: a marriage of inconvenience mediated by TLRs

The paradox of Leishmania‐macrophage interaction starts with the parasite residing and multiplying within macrophages, because these cells serve not only as metabolically active cells, wherein the reactive free radicals kill the parasite, but also as the antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) that activate antigen‐specific T cells, which activate or deactivate macrophages. In this marriage of inconvenience, TLRs play dual – pro‐leishmanial and anti‐leishmanial – roles accentuating the problem of segregating the TLR‐mediated host‐protective and disease‐promoting immune responses. Although TLRs do not play a decisive role in the outcome of infection, they can contribute to setting a bias to the T cell response, which eventually decides the fate of the parasite. Here, we discuss these functional paradoxes that pertain to the pro‐ or anti‐leishmanial roles played by TLRs.

The sandfly bite, transferring the promastigotes into an epidermal site, disrupts the tissue microenvironment and creates an acute inflammatory milieu by drawing in a variety of cells, in particular neutrophils and monocytes. The parasites infect the neutrophils, multiply therein and induce apoptosis. The amastigote‐laden apoptotic neutrophils are phagocytosed by macrophages 39. During the initial infection, activation of TLR‐2 by L. major lipophosphoglycan (LPG) down‐regulates the expression of TLR‐9, which provides host protection in genetically susceptible BALB/c mice 40. Another initial response to the invasion of L. major promastigotes is the neutrophil expressed elastases, a group of serine proteases that activates macrophages to clear pathogen via the TLR‐4 pathway 41, but inhibited by a Leishmania‐derived serine protease inhibitor 42. Corroboratively, TLR‐4‐deficient mice are shown to be susceptible to Leishmania infection 43. It was shown that C5a, a byproduct from Leishmania‐induced complement activation, regulates TLR4‐induced immune responses negatively 44, suggesting significant roles for complements and their receptors.

Complement receptors (CR1, CR3), mannose‐fucose receptors and fibronectin receptors expressed on the surface of macrophages play a deterministic role in binding and subsequent internalization 45. CR3 is employed by L. infantum and L. chagasi promastigotes for entry into macrophages by three major mechanisms: CR3 binding by C3bi‐opsonized promastigotes, CR3 binding to gp63 on promastigotes and promastigote surface LPG binding to CR1 and CR3 46, 47. The attachment of Leishmania species to macrophages was also enhanced by gp63 binding to fibronectin receptors, as proved by a strong homology between gp63 SRYD and fibronectin RGDS regions, inhibition of L. major attachment to macrophages by a SRYD containing synthetic octapeptide and immunoprecipitation of L. infantum and L. chagasi gp63 by anti‐fibronectin antibodies 48, 49.

While the CRs play important role in Leishmania binding and subsequent phagocytosis, TLRs may not play a significant role in phagocytosis. Although TLRs recognize pathogen, deficiency in none of the extracellular TLRs is reported to affect phagocytosis. However, the Leishmania‐expressed LPG that binds to TLR‐2 50 inhibits phagosomal maturation and phagolysosomal biogenesis by exclusion of cytoplasmic nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and occlusion of the vesicular proton‐ATPase from phagosomes. Rac‐1, a small signalling G‐protein, and ARF‐6 (ADP ribosylation factor‐6) assist in the entry of amastigotes inside macrophages 51, 52. By contrast, inclusion of TLRs in the phagosomal cargo has been shown to enhance phagosomal maturation and determinant selection 53. Such contrasting observations raise the question whether inclusion of a particular TLR in the phagosome enhances, while inclusion of other TLRs inhibits, its maturation; the issue remains unresolved.

Phagosomal maturation affects several cellular processes. First, amastigote harbouring vacuoles are rich in various hydrolases specific only to lysosomes such as cathepsin 54, and their membranes express several endosomal and lysosomal markers such as Ras‐related protein (Rab‐7), lysosomal‐associated membrane protein (LAMP)‐1 and LAMP‐2. The H+‐ATPase pump on these vacuoles maintains influx of protons and the intravacuolar acidic pH (4·7–5·2) required for proteolytic processing of antigens 54, 55. Secondly, the processing of phagocytosed antigen leads to the degradation of antigenic proteins into yet smaller peptides that are loaded onto major histocompatibility complex (MHC)‐II for surface presentation and recognition by the peptide‐specific TCR expressed on CD4+ T cells 56, 57. Thirdly, macrophages kill the intracellular amastigotes by generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS, RNS). Enzymes such as NADPH oxidase, phagocyte oxidase (Phox) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) help in oxidative burst and parasite clearance 52. Thus, the initial innate immune recognition of Leishmania by TLRs can have significant consequences on anti‐leishmanial immune response (Fig. 2).

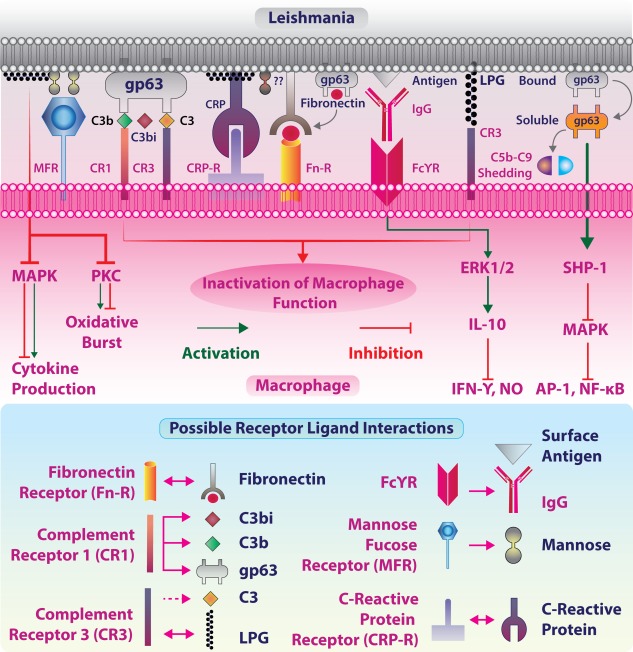

Figure 2.

Leishmania‐macrophage interaction: Leishmania–macrophage interaction begins at the site of infection. Promastigotes engage in various receptor‐mediated internalization processes minimally sensitizing the microbicidal functions. Leishmanial gp63 and lipophosphoglycan (LPG) are major antigens that interact with macrophage‐expressed fibronectin receptor (FnR), complement receptor 3 (CR3) and mannose fucose receptor (MFR) either actively or passively after binding to opsonins C3 and C‐reactive protein (CRP). LPG and gp63 are the two major factors responsible for leishmanial virulence. gp63 brings out the cleavage of opsonin C3b to inactive C3bi that facilitates promastigote uptake by interacting with CR3 receptor. Fcγ receptor (FcγR)‐mediated recognition of immunoglobulin (IgG)‐covered leishmanial surface antigens results in extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)‐mediated production of interleukin (IL)‐10, an anti‐inflammatory cytokine that suppresses the microbicidal activity of macrophages. gp63 is also implicated in directly activating SRC homology region‐2 domain containing phosphatase‐1 (SHP‐1) phosphatase, which inhibits mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling and cytokine production. LPG is also involved in the modulation of protein kinase C (PKC) and MAPK signalling.

The significance of innate immune recognition of leishmanial PAMPs is threefold: these molecules are conserved across Leishmania species, expressed constitutively in cells and play crucial roles in Leishmania pathogenesis. For successful transmission and subsequent immune‐evasion, Leishmania deploys numerous strategies aimed ultimately at suppressing the host immune response promoting its own survival. Conversely, the host activates co‐operatively the innate and adaptive modules of the immune systems for elimination of the parasite. Leishmania‐expressed surface molecular patterns include complex glycoconjugates, polysaccharides and lipopeptides, whereas intracellular molecular patterns such as nucleic acids [ssRNA, dsRNA from the RNA virus in Leishmania and unmethylated cytosine–phosphate–guanosine (CpG) in DNA]. These PAMPs elicit immune responses through their recognition by respective TLRs.

Infectious metacyclic promastigotes consist of a thick (∼20 µm) envelope or glycocalyx predominantly rich in proteophosphoglycans (PPGs) and serine proteases such as gp63 that are linked to plasma membrane by a GPI anchor 58. LPG and gp63 are attributed to parasite virulence and elicits pro‐leishmanial functions for establishment of infection in mononuclear phagocytes 59. LPG, the most abundant glycocalyx glycolipid on Leishmania promastigotes 60, along with glycosylphosphatidyl‐inositol (GPI) and glycoinositol‐phospholipids (GIPLs), are considered as the parasitic signature molecules that first interact with the host receptors including TLRs. In fact, GPI and GIPLs derived from Trypanosoma cruzi were found to be sufficient in provoking IL‐12, nitric oxide (NO) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α and mediating the anti‐parasitic response. TLR‐2 and TLR‐4 were found to be involved upon GPI and GIPLs stimulation, respectively, leading to proinflammatory cytokine production by murine macrophages 61. Similarly, recognition of LPG by TLR‐2 on murine macrophages 27 results in the production of NO that kills the parasite 62. gp63, an endoproteinase with maximal activity at pH 4 63, 64, aids in parasite internalization and survival in phagolysosome.

The signalling pathways for the cell surface and endosomal TLRs

While the cell surface‐located TLRs interact with soluble or pathogen surface‐anchored ligands, the intracellular endosomal TLRs provide an additional layer of protection when the nucleic acids are released following degradation of the pathogen. This arrangement of TLR display presents another paradox in handling a pathogen. The cell membrane‐located TLRs trigger the signals that activate the cellular leishmanicidal responses 65; thus, the Leishmania–macrophage interaction presents paradoxes that need to be resolved before a successful TLR‐targeted therapeutic can be devised.

TLRs signal primarily through four major adaptor proteins: myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), TIR domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP), TRIF [TIR domain containing adaptor protein inducing interferon (IFN)‐γ] or TRIF‐related adaptor molecule (TRAM) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between major TLR adaptors MyD88, TIRAP/MAL, TRIF and TRAM

| Parameters | Adaptors for TLR signalling | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MyD88 | TIRAP/MAL | TRIF/TICAM1 | TRAM/TICAM2 | |

| Protein type; cellular localization | Adaptor/scaffold; cytoplasm | Adaptor/scaffold; cytoplasm | Adaptor, associated with apoptosis; autophagosome | Adaptor; cytoplasm |

| Molecular weight | 33 233 Da (human) | 23 883 Da (human) | 76 422 Da (human) | 26 916 Da (human) |

| 33 753 Da (mouse) | 26 035 Da (mouse) | 79 230 Da (mouse) | 26 362 Da (mouse) | |

| Amino acids | 1–296 AA | 1–221 AA | 1–712 AA | 1–235 AA |

| Secondary structure | α Helix, Turn, β strand | α Helix and β strand | α Helix, Turn, β strand | α Helix, Turn, β strand |

| Binding region, domain(s) | 55–109: death domain; 159–296: TIR domain | 84–221 TIR domain | 390–460 TIR domain; 512–712: apoptosis‐inducing domain | 73–232 TIR domain |

| Downstream kinases | IRAK1, IRAK2 | IRAK2, TRAF‐6 | TRAF‐3, TRAF‐6, RIP‐1, IRF‐3 | IRAK‐1, IRAK‐4 |

| Interacting proteins | TIRAP, BMX, IL‐1RL1 also with IRF7, LRRFIP1 and LRRFIP2 | MyD88, BMX and TBK1 | Interacts with TICAM2 in TLR‐4 recruitment; also TBK1, TRAF6 and RIP1, AZI2/NAP1 | Interacts with IRF3, IRF7, TICAM‐1 in response to LPS; interacts with IL‐1R, IL‐1RAP, TRAF6, IRAK2, IRAK3 |

| Post‐translational modifications | Phosphorylation‐ phosphoserine (position‐244) | Phosphorylated by IRAK1, IRAK4, BTK; disulphide bond (between residues 89↔134 and 142↔174) | Phosphorylated by TBK1; polyubiquitinated by TRIM38 with ‘Lys‐48’‐linked chains, proteasomal degradation | Lipidation (N‐linked) position 2; phosphorylation‐ phosphoserine (position‐16) |

| Cell signalling | IL‐1R, IL‐18, all TLRs except TLR‐3 | TLR‐2, TLR‐4 | TLR‐3, TLR‐4 | TLR‐3, TLR‐4 (endocytosed) |

| Transcription factors | IRF1, NF‐κB | NF‐κB, ERK1, ERK2 and JNK | IRF3 and IRF7, NF‐κB and FADD | NF‐κB |

| Phenotype observed in deficient mice | Endotoxin‐tolerant 66, susceptibility to S. aureus 67, Th2 response in upper genital tract in Chlamydiasis 68; less clearance of L. major 27 | Impaired LPS‐induced splenocyte proliferation and cytokine production 71; signalling specificity in individual TLR signalling is lost 72 | Impaired innate immune responses to poliovirus 77; compromised host defence against pulmonary Klebsiella infection 78 | Defects in cytokine production in response to the TLR‐4 ligand, but not to other TLR ligands 80 |

| Disease observed in humans | Somatic mutation in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia 69, pyogenic bacterial infections with MyD88 deficiency 70 | Invasive Pneumococcal disease 73, 74 malaria 75 and susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis 76 | Susceptibility to herpes simplex encephalitis (IIAE6) is caused by hetero‐ or homozygous mutation in the TICAM1 gene 79 | – |

| Biological functions | JNK cascade; NF‐κB activation; Ab response; IFN‐type I biosynthesis; immunity to Gram‐positive bacterium | IL‐12, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐15 TNF‐α, IFN‐β production; NF‐κB/NIK activation; immunity to Gram‐positive bacterium | Positive regulation of autophagy; positive regulation of I‐κB kinase/NF‐κB cascade; response to exogenous dsRNA | Anti‐viral response; positive regulation of IκB kinase, IFN‐γ production, IL‐6 production and TLR‐4 signalling pathway |

Ab = antibody; BMX = Etk/BMX cytosolic tyrosine kinase; dsRNA = double‐stranded ribonucleic acid; ERK = extracellular regulatory kinase; FADD = Fas‐associating death domain‐containing protein; IFN‐γ = interferon gamma; IL = interleukin; IL‐1RL1 = IL‐1 receptor‐like; IRAK = IL‐1 receptor‐associated kinase; IRF1 = IFN = regulatory factor‐ 1; JNK = Janus kinase; LPS = lipopolysaccharide; LRRFIP = LRR Binding FLII interacting protein; MyD88 = myeloid differentiating factor 88; Mal = MyD88 adaptor‐like; NF‐κB = nuclear factor kappa light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells; NF‐κB: nuclear factor kappa B; NAP1 = NF‐κB‐activating kinase‐associated protein; NTD = N‐terminal domain; TBK‐1 = tank binding kinase‐1; TNF = tumour necrosis factor; NIK = NF‐κB‐inducing kinases; RIP‐1 = receptor‐interacting serine/threonine‐protein kinase 1; TLR = Toll‐like receptor; TICAM1 = TLR adaptor molecule 1; TICAM2 = TLR adaptor molecule 2; TIR domain = Toll/IL‐1 receptor (TIR) homology domain; TIRAP, Toll/IL‐1 receptor domain‐containing adapter protein; TRAF = TIR‐domain‐containing adapter‐inducing interferon‐β; TRAM = TRIF‐related adaptor molecule; TRIF = TIR‐domain‐containing adapter‐inducing interferon‐β; TRIM38 = tripartite motif‐containing protein 38 (E3 ubiquitin‐protein ligase‐TRIM38).

All TLRs except TLR‐3 trigger MyD88‐dependent signalling, whereas TLR‐3 signals via the MyD88‐independent pathway. TLR‐4 signals via both MyD88‐dependent and ‐independent pathways 65. In all cases, the ligand binding to TLR ectodomain initiates conformational changes in the intracytoplasmic domains, which recruit the adaptors to form a post‐receptor signalling complex that triggers the signalling 81. The MyD88‐dependent pathway also includes the adaptor TIRAP or MyD88 adapter‐like (MAL). These adaptors recruit IL‐1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK)‐4 that phosphorylates IRAK‐1 82, which phosphorylates IRAK‐2. IRAK‐2 plays an essential role in the ubiquitination of TNF‐α receptor‐associated factor 6 (TRAF6), that activates IκB kinase (IKK) and c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK). TRAF6 forms a complex with ubiquitin‐conjugating enzymes, Ubc13 and Uev1A, promoting the synthesis of lysine 63‐linked polyubiquitin chains and an unconjugated free polyubiquitin chain that subsequently activates the complex of transforming growth factor (TGF)‐α activated kinase (TAK1), TAK‐1 binding proteins TGF‐β‐activated kinase (TAB)‐1, TAB‐2 and TAB‐3 leading to the activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) (MAPKKK) module and IKK complex 83, 84. Activated TAK1 couples to the IKK complex, including scaffolding protein IKKγ or NF‐κB essential modulator (NEMO), leading to phosphorylation of IκBα (inhibitor of NF‐κB, alpha), nuclear translocation of NF‐κB and the expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes. MKK4/7 phosphorylation leads to the activation of another transcription factor named AP‐1 that also targets genes for cytokine production (Fig. 3).

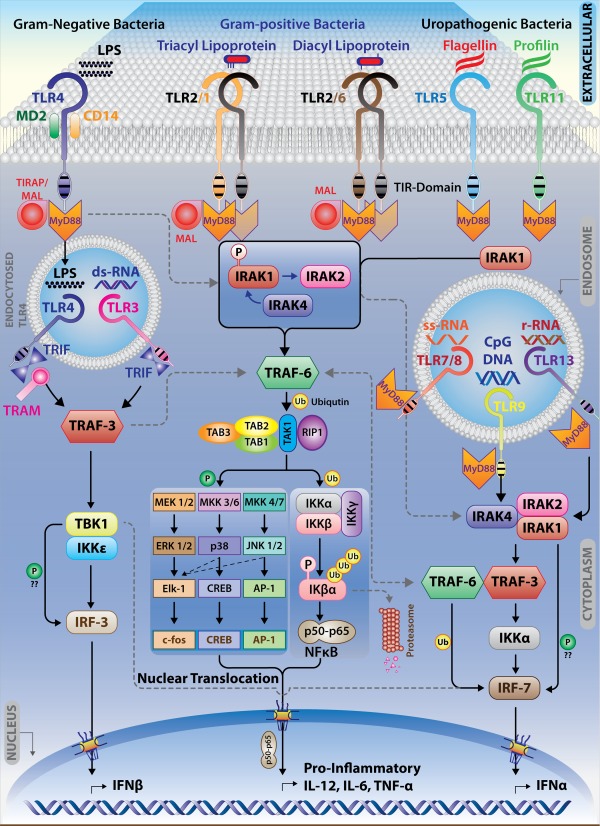

Figure 3.

Intracellular and Extracellular mode of Toll‐like receptor (TLR) signalling pathways: signalling heterogeneity in TLR pathways arises from the differential recognition of pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by different TLRs. In uninfected macrophages, TLR dimers are presumed to exist in a low‐affinity binding state. The binding of ligand is suggested to induce a conformational change that brings two Toll/IL‐1 receptor (TIR) domains into the close proximity of each other creating the signalling platform necessary for the recruitment of different adaptor molecules. Upon ligand binding, TLRs recruit major adaptor proteins: myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) and MyD88‐like adaptor protein/Toll IL receptor‐TIR domain containing adaptor‐like protein (MAL/TIRAP). MyD88 contains a C‐terminal TIR domain and an N‐terminal death domain, which is known to recruit the serine/threonine kinases of the IL‐1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) family. MAL/TIRAP is essential for TLR‐2 and TLR‐4 to signal through the MyD88 pathway. TRIF (TIR domain containing adaptor protein inducing IFN‐γ) or TRAM (TRIF‐related adaptor molecule) signal from the cytosolic region of TIR domain of the intracellular TLR‐3 and TLR‐4 leading to the activation of Interferon regulatory factor (IRF)‐3 via tank binding kinase (TBK)‐1 and I kappa B kinase (IKK)ɛ.

TLR‐3 and TLR‐4 from endosomes signal through the TRIF‐dependent pathway 85. TLR‐3 recruits TRIF directly to its TIR domain, while TLR‐4 first recruits a bridging adaptor for the interaction with TRIF 85, 86, 87. Endosomal TLR‐3 and TLR‐4 activation leads to IRF‐3‐regulated IFN‐γ production 88. This pathway follows IRF‐3 activation by non‐canonical IκB kinase homologues IKKɛ and TANK binding kinase TBK‐1. TRAF3 co‐operates with TRIF and TBK1 to regulate TRIF‐dependent IFN‐γ production positively. TRAF3 undergoes K63‐linked auto‐ubiquitination in response to TLR‐3 89, 90. Proteasome‐mediated TRAF3 degradation is necessary for MAPK activation and proinflammatory cytokine production. Although Leishmania is devoid of dsRNA, a well‐known ligand for TLR‐3, RNA from LRV‐1, an RNA virus in L. guyanensis, serves as a TLR‐3 ligand and helps in the production of the cytokines and chemokines that support parasite survival 91, 92.

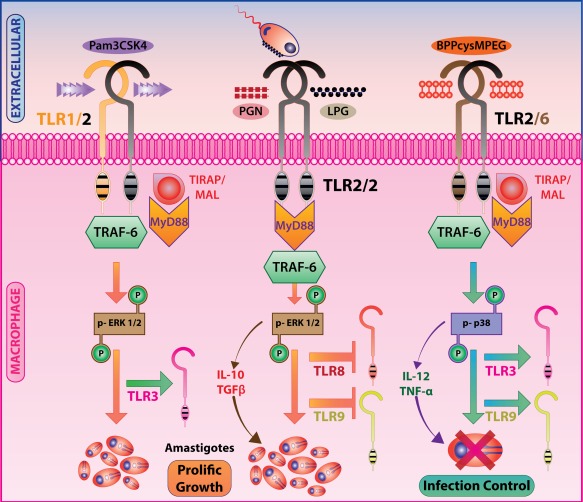

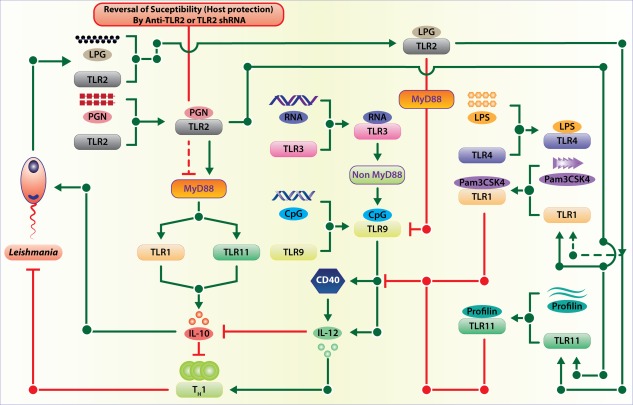

L. donovani tailors TLR‐2 signalling for subverting IL‐12 production. Arabinosylated lipoarabinomannan (Ara‐LAM), a TLR‐2 agonist, up‐regulates TLR‐2 expression significantly in macrophages, whereas abrogation of TLR‐2 signalling using specific siRNA leads to diminished proinflammatory cytokine production 93, suggesting that TLR‐2 plays an anti‐parasitic role. As TLR‐2 signals through MyD88, corroborating this observation, MyD88‐deficient mice were found to be more susceptible to L. major infection accompanied by expression of negative regulators suppressors of cytokine signalling family (SOCS)1 and SOCS3 27. L. Mexicana‐expressed p8 proteoglycolipid complex (p8PGLC) glycoconjugates induce TLR‐4‐dependent production of TNF‐α and CCL5. L. pifanoi amastigote‐expressed p8PGLC binds to TLR‐4 and initiates cytokine signalling 32. TLR‐4 signalling in L. donovani infection is suppressed by two major mechanisms: first, release of TGF‐β, that activates a de‐ubiquitinating enzyme complex A20 through SRC homology region‐2 domain containing phosphatase‐1 (SHP‐1); secondly, active inhibition of IRAK‐1. These effects ensure temporary activation of inflammatory signalling pathways favouring L. donovani survival in macrophages 22. Infection of L. panamensis results in TLR‐1, TLR‐2, TLR‐3 and TLR‐4 activation in human primary macrophages, and when stimulated with their respective ligands these TLRs induce TNF‐α production in equivalent amounts. The same study also validates the indispensability of MyD88/TRIF in TLR‐4 signalling. Mouse MyD88/TRIF‐deficit bone marrow‐derived macrophages were unable to produce TNF‐α, indicating the TLR‐4 dependence on these adaptor proteins for signalling 27. The TLR‐1–TLR‐2 heterodimer recognizes triacylated lipopeptides, whereas the TLR‐2–TLR‐6 heterodimer recognizes diacyl lipopeptides. This heterodimeric assembly of TLR‐2 with TLR‐1–TLR‐6 regulates L. major infection differentially in murine macrophages. In L. major infection, TLR‐1 and TLR‐2 expression and TLR‐1–TLR‐2 associations increase, but the TLR‐2–TLR‐6 association decreases. PEGylated bisacycloxypropylcysteine (BPPcysMPEG), a ligand for the TLR‐2–TLR‐6 heterodimer, induces IL‐12 and iNOS expression and anti‐leishmanial function 18 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Toll‐like receptor 2 (TLR‐2) heterodimers lead to dichotomous immune responses to Leishmania infection: Pam3‐Cys‐Ser‐Lys4 (Pam3CSK4) induced TLR‐1–TLR‐2 hetero‐dimerization and peptidoglycan (PGN)‐induced probable TLR‐2 homodimerization result in extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)‐1/2 phosphorylation and subsequent secretion of interleukin (IL)‐10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β promoting intracellular parasite survival, whereas PEGylated bisacycloxypropylcysteine (BPPcysMPEG) induced TLR‐2–TLR‐6 heterodimerization results in p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)‐mediated IL‐12 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α production and parasite killing.

Flagellin and profilin play an important role in the motility of the parasite and invasion into the host cell. Flagellated pathogens are speculated to sensitize TLR‐5 while TLR‐11 recognizes profilin, also known as soluble Toxoplasma antigen, which helps in IL‐12 production 94. In L. major infection, TLR‐11 is observed to suppress TLR‐9 expression and CpG‐induced IL‐12 production. Similarly, LPG on virulent parasites interacts with TLR‐2 and reduces TLR‐9 expression and CpG‐induced IL‐12 production. In L. major‐infected macrophages, TLR‐9 modulates TLR‐1, TLR‐2 and TLR‐3 but not TLR‐7 expression. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from TLR‐9‐deficient mice infected with L. major had reduced TNF‐α and IL‐12 production 18. Crude soluble leishmanial antigen‐vaccinated BALB/c mice were vulnerable to subsequent challenge by L. major infection unless these mice were treated with R848 and imiquimod, ligands for TLR‐7 and TLR‐8, during vaccination 95. This observation suggested that TLR‐7 and TLR‐8 ligands might work as adjuvants for priming with leishmanial antigens.

Involvement of TLRs in leishmania infection in genetically resistant hosts

The limited effects of the TLR deficiency or TLR signalling deficiency on Leishmania infection have raised the question of whether TLRs determine the genetic resistance or susceptibility to Leishmania infection. The initial studies involved scanning resistance or susceptibility among inbred mouse strains 96. Mapping of transient susceptibility towards L. donovani using a recombinant inbred strain pointed to identification of the Lsh locus on chromosome‐1 97. The allele that confers resistance is dominant, and the same locus was reported later to be involved in conferring susceptibility to other intracellular infection. The genetic basis of control of L. donovani infection in later stages has also been reported mainly by examining the influence of various chromosomal segments on C57BL/10ScSn and BALB/c backgrounds. The later stage of infection is influenced by the haplotype at H2 genomic region (MHC) and by the immune response locus on chromosome 2 (Ir2) 98. The H2 region in mice is equivalent to the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) region in humans that encodes complement component and antigen processing genes 99. The presence of H2a, H2b, H2k, H2k/b and H2r haplotypes on the C57BL/10ScSn background resulted in a low parasite burden, whereas H2b/d, H2d, H2f and H2q mice had a high parasite burden 98, 100, 101. The lower parasite burden in the resistant strain compared to the susceptible strain after L. donovani infection indicated that some susceptibility genes are involved innately in limiting parasite growth 102. The genes and loci involved in controlling the response to L. major infection are identified as Lmr12 (Lmr12 – L. major response 12) and Dice1b (Dice1b – determination of IL‐4 commitment 1B) on chromosome 16. Subsequent identification of the susceptibility gene at this locus (Lsh, Nramp, Slc11a1) helped to decipher the molecular mechanism of acute susceptibility 103 and the mechanism by which Nramp/Slc11a1 (Nramp – natural resistance‐associated macrophage protein 1; Slc11a1 – solute carrier family II member 1) influences the response to L. infantum and L. mexicana 100, 104.

In 1986, CD4+ T helper cells were shown to have two functionally distinct clones: one secreting IL‐2 and IFN‐γ and the other secreting IL‐4 105, and this functional dichotomy of T helper cells was reviewed extensively 106. Immediately after this discovery, T helper (Th) subset polarization in L. major infection 107, 108 and the co‐existence of both Th1 and Th2 cells but Th1 suppression by Th2 cells in L. donovani infection 109 were demonstrated. These observations established an association between the resistance to Leishmania infection and selective activation of Th1 cells. Similarly, the susceptibility to Leishmania infection was associated with Th2 cells. Meanwhile, as TGF‐β‐deficient mice were produced by embryonic stem cell manipulation, this led to a flurry of studies with cytokine (or cytokine receptor) or transcription factor‐deficient mice. All these studies identified IL‐4 and IL‐10 as the major susceptibility factors 110, 111, 112 and IL‐12 and IL‐12R as the resistance factors 113, 114. Using the cell‐specific gene knock‐out system, it was observed that macrophage‐, but not T cell‐secreted IL‐10, was responsible for the susceptibility to Leishmania infection. Further heterogeneity was observed when mice with IL‐4R‐deficiency on different cell types were produced 115. Because no TLR‐deficient mice on a genetically resistant background are seen to be absolutely susceptible to Leishmania infection, the relative contribution of the above‐mentioned genetic factors and TLRs to resistance or susceptibility to this parasite remains unsettled. As TLR‐2‐ and TLR‐4‐deficient mice showed larger lesions and a higher parasite burden than that observed in the wild‐type C57BL/6 mice, due to a predominant Th2 response, it is argued that TLRs modulate Leishmania infection through the T cell response. The mice deficient in TLR‐1 or TLR‐6 or both did not exhibit escalated Leishmania infection 30. By contrast, in one study, TLR‐2‐deficient mice had enhanced, long‐term protection and control of L. donovani infection 116. Mammalian homologue B1 of Caenorhabditis elegans Unc‐93 is implicated in endosomal translocation of nucleic acid sensing TLRs from endoplasmic reticulum to endolysosomes. As UNC39B1 mutant mice showed enhanced footpad swelling with increased IL‐10, but decreased IL‐12 levels, it is believed that UNC39B1 gene modulates signalling through TLR‐3, TLR‐7 and TLR‐9. The TLR‐3/TLR‐7/TLR‐9 triple TLR knockout mice were susceptible to Leishmania infection, whereas TLR‐7/TLR‐9 double‐deficient mice exhibited a mixed phenotype and the single TLR‐deficient mice had only a transient, if any, effect on Leishmania infection. These findings provide insight into the redundant and essential roles of intracellular TLRs – TLR‐3, TLR‐7 and TLR‐9 – in inducing a host‐protective Th1 response and resistance against L. major in genetically resistant C57BL/6 mice 117. TLR effects on the resistance or susceptibility to Leishmania infection may therefore be executed through Th subsets or through the macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), which present antigens to T cells for activation and differentiation to effector T cell subsets. However, as no TLR has been reported to reverse the resistant phenotype in mice, it is possible that TLRs play more of a modulatory role in innate and adaptive anti‐leishmanial immune responses than any decisive role in the infection.

TLRs as modulators of innate and adaptive immunity

As Leishmania invades its host, some ligands bind to non‐TLRs and the PAMPs bind to TLRs, evoking a huge array of signals that are decoded and translated to extremely broad effector responses which can be categorized into innate and adaptive immune responses. The innate immune responses include enhanced phagosomal maturation, activation of complement system proteins, opsonization‐facilitated phagocytosis and production of type 1 interferons. Innate immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cells target the Leishmania‐infected macrophages in a cytokine‐dependent manner, as these cells have a reduced expression of MHC molecules 118. In addition, exposure of DCs to TLR‐dependent Th1‐inducing stimuli activated NK cells, whereas the DCs exposed to TLR‐independent non‐pathogenic stimuli failed to promote NK cell activation 119, as both Th1 induction and IFN‐γ production from NK cells require IL‐12, named originally as NK cell stimulatory factor 120. Leishmania‐specific activation of NK cells by LPG–TLR‐2 interaction enables NK cells to perform leishmanicidal functions 50, which could be because of TLR‐9 activation 121. TLR‐mediated NK cell activation is affected by a wide range of pathogenic microbiota such as bacteria and viruses 122. TLR‐9 is reported to limit early infection and promote a host‐protective adaptive immune response 123. Similarly, TLR‐4 or MyD88 silencing studies 124 showed that gp29 (β‐1,4 galactose terminal glycoprotein from L. donovani), a ligand for TLR‐4, induced IL‐12 and NO production but attenuated IL‐10 production. The observation suggested a potential host‐protective role for the TLR‐4–MyD88–IL‐12 pathway.

TLRs play important regulatory roles in the T cell response by affecting determinant selection and co‐stimulation of T cells. Macrophages, dendritic cells or any other antigen‐presenting cells must provide three signals for T cell activation and differentiation: the first signal is delivered through the T cell receptor (TCR), as it recognizes the peptide antigen in a complex with MHC molecules 125; the second signal is delivered when CD28 and CD40‐L on T cells recognize CD80/CD86 and CD40, respectively, on the antigen‐presenting cells, 126, 127, and the third signal is delivered by the cytokines released from the antigen‐presenting cells and bind to respective cytokine receptors on T cells 128, 129. Th1 polarization is induced by IL‐12 and type‐1 interferons from APCs, whereas Th2 polarization requires IL‐4 production by T cells (Fig. 5). Medzhitov et al. showed that a constitutively active mutant of human Toll transfected into human cell lines induced the activation of NF‐κB and the expression of NF‐κB‐controlled genes for the inflammatory cytokines IL‐1, IL‐6 and IL‐8, as well as the expression of the co‐stimulatory molecule CD80, which is required for the activation of naive T cells 4. Because the T cells were transfected with the TLR, this report was an alternative‐exaggeration of the innate response influencing the adaptive immune response. The adoption of that particular system precluded the testing of determinant selection for the antigen‐specific receptors for recognition by T cells and the expression of co‐stimulatory molecules on antigen‐presenting cells, although both functions are indispensable for the clonal activation of T cells.

Figure 5.

Toll‐like receptor (TLR) and CD40 drive evolution of adaptive immune response. Injury or infection releases pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [or danger‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)] that are recognized by TLRs on the residential histiocytes releasing chemokines. These chemokines draw different cell types to the site of infection. Mono‐mac cells and dendritic cells take up antigens, mature and present the antigens to T cells. These cells also secrete cytokines in response to TLR activation. These cytokines influence T cell differentiation into different effector subsets; accordingly, the fate of the parasite is decided.

For determinant selection, in particular, in the context of MHC class II, phagocytosis of an exogenous antigen and subsequent maturation of the phagosome play important roles in antigen processing and loading of the peptides to MHC class II molecules. Involvement of TLR during phagocytosis leads to selection of one of two constitutive and inducible modes of phagosomal maturation. It was reported that the inducible, but not the constitutive, phagosomal maturation is dependent upon the involvement of TLR during the phagocytosis 130. The presence of TLR ligands within the phagocytosed antigen compartment can increase the efficiency of antigen presentation 53. Only TLR‐2 is recruited specifically to macrophage phagosomes. A point mutation in the receptor abrogates inflammatory responses to yeast and Gram‐positive, but not to Gram‐negative, bacteria. Thus, during the phagocytosis of pathogens, two classes of innate immune receptors co‐operate to mediate host defence: phagocytic receptors, such as the mannose receptor for signalling particle internalization, and TLRs for sampling the contents of the vacuole and trigger the host‐protective inflammatory response, as appropriate for a specific organism 131.

TLR signalling results in the transcription of cytokines and co‐stimulatory molecules. TLR signalling regulates the endocytic pathway for phagosome–lysosome maturation and antigen presentation 130. Once TLR‐2 and TLR‐4 are recruited to phagosomes and activated by microbial cell wall components, phagosome maturation is regulated by MyD88 and p38 MAPK 131, 132. The process of impairment of phagosomal maturation by leishmanial antigen LPG requires depolymerization of periphagosomal F‐actin. The LPG‐dependent accumulation of F‐actin around phagosomes serves as an impediment for the recruitment of lysosomal marker LAMP‐1 and PKCα to phagosome 133. Rab7 and LAMP‐1 proteins are required for fusion of lysosomes and phagosomes 134, 135. The delayed maturation of phagolysosomes results in an expanded time‐span during which hydrolase‐sensitive promastigotes can metamorphose into relatively resistant amastigotes. Silencing of synaptotagmin‐V (Syt‐V), an exocytosis regulator, by siRNA revealed that Syt‐V helps in phagolysosome biogenesis by regulating the acquisition of cathepsin‐D and vesicular proton ATPase pump. L. donovani targets Syt‐V to avert phagosome acidification, prolonging its intracellular survival 55. Rab family proteins are the master regulators for both phagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. TLR signalling helps in p38 MAPK phosphorylation, increasing the rate of endocytic trafficking by activation of guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor via phosphorylation (GDI). Upon activation, GDI serves as a GTP loader which replenishes the exhausted Rab proteins cytosolic pools, making them available again for endocytic cycling. TLR‐mediated control of phagosome maturation indeed affects the efficiency of antigen presentation 53, 130. Subversion of endosomal signalling and impaired lysosome–endosome fusion results in capsizing of the MHC‐II antigen presentation by APCs, facilitating amastigote growth and evasion from T cells. Phagosome maturation is immunologically important for the assembly of antigenic peptide with MHC class II on APCs and transport to the plasma membrane for recognition by T cells 136. Although this facilitates ideal T cell activation against pathogenic micro‐organisms, it can also retaliate immunologically to produce an adverse autoimmune response when the antigen was derived from apoptotic cells 137. Blander et al. reported that TLR signalling led to loading of specific antigenic peptides onto MHC II, whereas those peptides from the apoptotic cells were not selected for binding to MHC II 53. L. donovani inhibits both constitutive and IFN‐γ‐activated MHC II expression on APCs 138 and sequesters the MHC molecule within the phagolysosomes to reduce its availability for antigen presentation 139. By contrast, L. amazonensis does not tamper with the MHC molecules expression but inhibits peptide loading indirectly, as intracellular MHC molecules are internalized and degraded by amastigotes. Thus, Leishmania proficiently subverts phagolysosomal maturation and impairs the TCR–MHC–peptide assembly, effectively nullifying T cell sensitization 140, 141.

TLR–CD40 cross‐talk

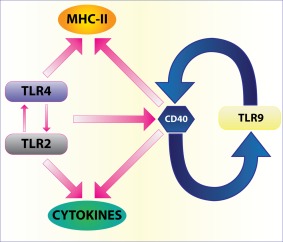

Leishmania is known to skew the CD40 signalling in the host and shifts the pathway to promote its intracellular existence within macrophages 142. CD40, a molecule expressed on B cells, monocyte/macrophages, follicular DCs, fibroblasts and endothelial cells, is known to provide a co‐stimulatory signal for T cell activation and isotype‐switching 143. The counteracting cytokines IL‐12 and IL‐10 are induced by activation of p38 MAPK and extracellular‐regulated kinase (ERK)‐1/2, respectively 144. CD40 expression was enhanced by different TLR ligands such as poly I:C, LPS and CpG, whereas CD40 stimulation enhanced the expression of only TLR‐9. Macrophages stimulated with CpG and CD40 ligand augmented IL‐12 production compared to CpG treatment alone 25. L. major DNA‐induced TLR‐9 activation led to IL‐12 secretion 26 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Toll‐like receptor (TLR)–CD40 loop: many TLRs increase CD40 expression but only TLR‐9, an intracellular TLR that recognizes unmethylated cytosine–phosphate–guanosine (CpG) DNA of Leishmania, enhances CD40 expression. This can be considered as a positive feedback loop for enhancing production of interleukin (IL)‐12 and promoting T helper type 1 (Th1) response. The figure also shows TLR‐activated major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression. This effect is connected to CD40 expression and dendritic cell (DC) maturation.

CD40‐mediated activation of adaptive immunity was modulated by TLRs. Following TLR–PAMPs interaction, DCs mature by expressing MHC II and CD80/CD86 145. CD8+ cytotoxic T cell expansion was observed more in combined stimulation with TLR‐7 and CD40 than that observed with either agent alone. These reports provide evidence of CD40–TLR synergy that affects DC maturation and activation, and that induces differentiation of CD4+ Th cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.

The regulatory circuitry of TLRs that elicits host‐protective or disease‐promoting response

As pathogens express various types of molecular patterns on their surface, it is logical to assume that multiple TLRs on the host cell surface are engaged by a pathogen. These TLRs display functional specificities that may either synergize or counter each other leading to alternative outcomes of an infection. Thus, multiple TLRs working in tandem essentially propose that different TLRs interact with each other leading to differential outcome of the infection (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Inter‐Toll‐like receptor (TLR) regulatory circuitry that controls the outcome of Leishmania infection. Multiple TLRs are involved in the infection by two different modes: directly by Leishmania‐derived pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) interacting with respective TLRs and indirectly by one TLR regulating some other TLRs. Although the first mode of multiple TLR involvement by Leishmania‐derived ligands is amply demonstrated, the second mode that involved inter‐TLR regulation is yet to be demonstrated.

First, multiple TLRs interacting with their respective ligands increase the avidity of the host–pathogen interaction and this increased avidity may be necessary for the ensuing process of pathogen internalization and survival or death inside the host cell. As a result, such interaction may play a prominent role in colonization of a pathogen in a particular tissue where the target host cells express the receptors in adequate numbers.

Secondly, all cell surface TLRs signal through MyD88 and TIRAP, whereas only TLR‐4 also signals through TRIF. This arrangement of TLR signalling leads to three possibilities: (1), the restricted antigenic specificity of a cell surface TLR cannot lead to specific functions, as all these TLRs signal through MyD88 and TIRAP, whereas TLR‐4 remains specific, as it signals through both the pathways; (2), multiple TLRs signalling through MyD88 can optimize the efficiency of usage of intracellularly available MyD88 and TIRAP increasing the overall signal strength – TLR‐4 achieves increased signal strength by signalling through both MyD88 and TRIF; and (3), intracellular competition between TLRs for recruiting MyD88 may lead to recruiting more of MyD88 to one TLR that has the highest affinity for MyD88 depriving the one with the weakest affinity; the cell becomes tolerized to the PAMP that is specific for the weakest TLR. The tolerization to TLR ligands can thus be imparted by the non‐availability of the adaptor proteins either by competition or by successive stimulation.

Thirdly, because ligand binding to a TLR results in recruitment of the adaptor(s) to it, binding of ligands to multiple cell surface TLRs will trigger competition between these TLRs. In order to optimize the effect TLR–PAMP interactions, expression of the less important TLRs may therefore be inhibited implying an interaction between the cell surface TLRs. The opposite effects may be observed when these TLRs work together. For example, TLR‐1 or TLR‐6 may dimerize with TLR‐2. However, the biological effects of these two dimers, TLR‐1–TLR‐2 and TLR‐2–TLR‐6, are opposite 18. Therefore, it is logical to assume that in order to polarize the response, the initial interaction of Leishmania with macrophages through TLR‐1–TLR‐2 is likely to enhance TLR‐1 expression but reduce TLR‐6 expression or its association with TLR‐2 18. This effect may minimize the competition and optimize the rate of signal flow through subsequent signalling steps.

Fourthly, when the PAMP–TLR interactions are followed by their internalization, as in the case of Leishmania, it is possible that the initial TLR–PAMP interactions will modulate the expression and function of the intracellular TLRs, which recognize the pathogen‐derived nucleic acids. As nucleic acids are released after degradation of the internalized parasite and their recognition by the endosomal TLRs may lead to further degradation of the parasite, it is logical that the initial TLR‐2–LPG interaction leads to the reduced expression and function of TLR‐9 in Leishmania‐infected macrophages. The parasite dampens the CD40–TLR‐9 feed‐forward motif used by the host to enhance its anti‐leishmanial activity.

Finally, multiple TLRs apparently work in tandem and in sequence, providing an option to the host, and perhaps also to the parasite, to modulate the ongoing immune response to reinstate immune homeostasis or establish infection, respectively. In L. major infection in mice, the initial TLR‐2–LPG interaction increases TLR‐1 and TLR‐11 expression but reduces TLR‐4 and TLR‐9 expression. In visceral leishmaniasis patients, high TLR‐4 and TLR‐9 expression was observed 146. Both these modulations are crucial for the establishment of Leishmania infection, as silencing TLR1, TLR2 and TLR11 reduce the parasite load drastically in susceptible BALB/c mice. CpG works significantly better in the TLR‐2 blocked condition, re‐emphasizing the negative effects of TLR‐2 on TLR‐9 function 40. While TLR‐1, TLR‐2 and TLR‐11 silencing increased the Th1 response, TLR‐6 and TLR‐9 silencing promoted Th2 and the regulatory T cell (Treg) response in L. major infection, suggesting that the initial TLR involvements affect the ensuing adaptive immune responses that decide the final outcome of the infection. By contrast, naturally induced Treg [CD4+CD25+forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3+)] cells were found to be depleted by ∼50% in TLR‐2–/– mice in many other disease models such as candidiasis and tumour 147, 148. The Treg depletion promoted IL‐10 production and disease severity. In L. donovani‐infected C57BL/6 mice, the CD4+CD25−FoxP3− but not the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells proliferate preferentially. These cells and NK cells act as sources of IL‐10 149, 150, making it unlikely that deficient Treg cell activity accounted for resistance in TLR2–/–mice. The kinetics of L. donovani liver infection in TLR2–/– and IL‐10–/– mice were notably similar 151. Therefore, a more detailed study on the organ‐specific contribution of TLRs in the infections that involve multiple lymphoid and non‐lymphoid organs is required.

Conclusion

This review analyses the roles played by TLRs in Leishmania infection and also uncovers some fundamental principles that are applicable to other infections. Some of these principles are: (i) TLR dimerization increases the breadth of ligand recognition; (ii) TLRs exhibit redundancy in ligand recognition spectrum; (iii) multiple TLRs are involved simultaneously in pathogen recognition; (iv) such combinations of multiple TLRs simultaneously recognizing their respective ligands can influence the nature of the elicited immune response; (v) simultaneous activation of multiple TLRs imply competition between the TLRs for the recruitment of the adaptors; (vi) such a competition may form the basis of signalling specificity despite gross antigen recognition and limited signalling options; (vii) extracellular TLRs can regulate the expression and function of intracellular TLRs or vice versa; (viii) TLRs interact between themselves to influence the final outcome of an infection; (ix) TLRs are capable of playing dual roles, i.e. eliciting both proinflammatory and anti‐inflammatory responses; (x) the interactions between TLRs display both feedback inhibition and feed‐forward motifs; and (xi) TLRs can influence multiple parameters of adaptive immune response, including determinant selection, co‐stimulatory molecules expression and cytokine production. This review thus describes the specificity, redundancy and regulatory roles played by TLRs in immune responses.

Disclosure

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1. Anderson KV, Jurgens G, Nusslein‐Volhard C. Establishment of dorso‐ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo: genetic studies on the role of the Toll gene product. Cell 1985; 42:779–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lemaittre B, Nicholas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorso‐ventral regulatory gene cassette spatzel/Toll/cactus controls the potent anti‐fungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 1996; 86:973–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lemaitre B, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. Drosophila host defense: differential induction of antimicrobial peptide genes after infection by various classes of microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:14614–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medzhitov R, Preston‐Hurlburt P, Janeway CA. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature 1997; 388:394–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I et al Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 1998; 282:2085–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poltorak A, Ricciardi‐Castagnoli P, Citterio S, Beutler B. Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and Toll‐like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97:2163–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beutler B, Poltorak A. Positional cloning of LPS, and the general role of Toll‐like receptors in the innate immune response. Eur Cytokine Netw 2000; 11:143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janeway CA. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1989; 54: 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medzhitov R, Janeway CA. Jr Innate immune recognition and control of adaptive immune responses. Semin Immunol 1998; 10:351–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kędzierski Ł, Montgomery J, Curtis J, Handman E. Leucine‐rich repeats in host–pathogen interactions. Arch Immunol Ther Exp 2004; 52:104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006; 124:783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010; 140:805–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature 2007; 449:819–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamali‐Sarvestani E, Rasouli M, Mortazavi H, Gharesi‐Fard B. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iranian patients. Cytokine 2006; 35:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsumoto C, Oda T, Yokoyama S et al Toll‐like receptor 2 heterodimers, TLR2/6 and TLR2/1 induce prostaglandin E production by osteoblasts, osteoclast formation and inflammatory periodontitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012; 428:110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jin MS, Kim SE, Heo JY et al Crystal structure of the TLR1‐TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri‐acylated lipopeptide. Cell 2007; 130:1071–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang JY, Nan X, Jin MS et al Recognition of lipopeptide patterns by Toll‐like receptor 2‐Toll‐like receptor 6 heterodimer. Immunity 2009; 31:873–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pandey SP, Chandel HS, Srivastava S et al Pegylated biscyclopropylcysteine a diacylated lipopeptide ligand of TLR6, plays a host‐protective role against experimental Leishmania major infection. J Immunol 2014; 193:3632–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raetz M, Kibardin A, Sturge CR et al Cooperation of TLR12 and TLR11 in the IRF8‐dependent IL‐12 response to Toxoplasma gondii profilin. J Immunol 2013; 191:4818–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Desjardins M, Descoteaux A. Inhibition of phagolysosomal biogenesis by the Leishmania lipophosphoglycan. J Exp Med 1997; 185:2061–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chandra D, Naik S. Leishmania donovani infection down‐regulates TLR2‐stimulated IL‐12p40 and activates IL‐10 in cells of macrophage/monocytic lineage by modulating MAPK pathways through a contact‐dependent mechanism. Clin Exp Immunol 2008; 154:224–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Srivastav S, Kar S, Chande AG, Mukhopadhyaya R, Das PK. Leishmania donovani exploits host deubiquitinating enzyme A20, a negative regulator of TLR signaling, to subvert host immune response. J Immunol 2012; 189:924–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silva‐Barrios S, Smans M, Duerr CU et al Innate immune B cell activation by Leishmania donovani exacerbates disease and mediates hypergammaglobulinemia. Cell Rep 2016; 15:2427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cezário GA, Oliveira LR, Peresi E et al Analysis of the expression of Toll‐like receptors 2 and 4 and cytokine production during experimental Leishmania chagasi infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2011; 106:573–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chandel HS, Pandey SP, Shukla D et al Toll‐like receptors and CD40 modulate each other's expression affecting Leishmania major infection. Clin Exp Immunol 2014; 176:283–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abou Fakher FH, Rachinel N, Klimczak M, Louis J, Doyen N. TLR9‐dependent activation of dendritic cells by DNA from Leishmania major favors TH1 cell development and the resolution of lesions. J Immunol 2009; 182:1386–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Veer MJ, Curtis JM, Baldwin TM et al MyD88 is essential for clearance of Leishmania major: possible role for lipophosphoglycan and Toll‐like receptor 2 signaling. Eur J Immunol 2003; 33:2822–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fernández‐Figueroa EA, Imaz‐Rosshandler I, Castillo‐Fernández JE et al Down‐regulation of TLR and JAK/STAT pathway genes is associated with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis: a gene expression analysis in NK cells from patients infected with Leishmania mexicana . PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10:e0004570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shweash M, McGachy HA, Schroeder J et al Leishmania mexicana promastigotes inhibit macrophage IL‐12 production via TLR‐4 dependent COX‐2, iNOS and arginase‐1 expression. Mol Immunol 2011; 48:1800–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Halliday A, Bates PA, Chance ML, Taylor MJ. Toll‐like receptor 2 (TLR2) plays a role in controlling cutaneous leishmaniasis in vivo, but does not require activation by parasite lipophosphoglycan. Parasit Vectors 2016; 9:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guerra CS, Macedo Silva RM, Carvalho LOP, Calabrese KDS, Bozza PT, Côrte‐Real S. Histopathological analysis of initial cellular response in TLR‐2 deficient mice experimentally infected by Leishmania (L.) amazonensis . Int J Exp Pathol 2010; 91:451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whitaker SM, Colmenares M, Pestana KG, McMahon‐Pratt D. Leishmania pifanoi proteoglycolipid complex P8 induces macrophage cytokine production through Toll‐like receptor 4. Infect Immun 2008; 76:2149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gallego C, Golenbock D, Gomez MA, Saravia N. Toll‐like receptors participate in macrophage activation and intracellular control of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis . Infect Immun 2011; IAI–01388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weinkopff T, Mariotto A, Simon G et al Role of Toll‐like receptor 9 signaling in experimental Leishmania braziliensis infection. Infect Immun 2013; 81:1575–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carneiro PP, Conceição J, Macedo M, Magalhães V, Carvalho EM, Bacellar O. The role of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in the killing of Leishmania braziliensis by monocytes from patients with cutaneous Leishmaniasis. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0148084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ives A, Masina S, Castiglioni P et al MyD88 and TLR9 dependent immune responses mediate resistance to Leishmania guyanensis infections, irrespective of Leishmania RNA virus burden. PLOS ONE 2014; 9:e96766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Killick‐Kendrick R. The life‐cycle of Leishmania in the sandfly with special reference to the form infective to the vertebrate host. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 1990; 65:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C et al Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLOS ONE 2012; 7:e35671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guimarães‐Costa AB, Nascimento MT, Froment GS et al Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:6748–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Srivastava S, Pandey SP, Jha MK, Chandel HS, Saha B. Leishmania expressed lipophosphoglycan interacts with Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐2 to decrease TLR‐9 expression and reduce anti‐leishmanial responses. Clin Exp Immunol 2013; 172:403–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ribeiro‐Gomes FL, Moniz‐de‐Souza MCA, Alexandre‐Moreira MS et al Neutrophils activate macrophages for intracellular killing of Leishmania major through recruitment of TLR4 by neutrophil elastase. J Immunol 2007; 179:3988–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Faria MS, Reis FC, Azevedo‐Pereira RL, Morrison LS, Mottram JC, Lima AP. Leishmania inhibitor of serine peptidase 2 prevents TLR4 activation by neutrophil elastase promoting parasite survival in murine macrophages. J Immunol 2011; 186:411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kropf P, Freudenberg N, Kalis C et al Infection of C57BL/10ScCr and C57BL/10ScNCr mice with Leishmania major reveals a role for Toll‐like receptor 4 in the control of parasite replication. J Leuko Biol 2004; 76:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hawlisch H, Belkaid Y, Baelder R, Hildeman D, Gerard C, Köhl J. C5a negatively regulates Toll‐like receptor 4‐induced immune responses. Immunity 2005; 22:415–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kane MM, Mosser DM. Leishmania parasites and their ploys to disrupt macrophage activation. Curr Opin Hematol 2000; 7:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mosser DM, Vlassara HE, Edelson PJ, Cerami A. Leishmania promastigotes are recognized by the macrophage receptor for advanced glycosylation end products. J Exp Med 1987; 165:140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mosser DM, Edelson PJ. The third component of complement (C3) is responsible for the intracellular survival of Leishmania major . Nature 1987; 327:329–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rizvi FS, Ouaissi MA, Marty B, Santoro F, Capron A. The major surface protein of Leishmania promastigotes is a fibronectin‐like molecule. Eur J Immunol 1988; 18:473–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Soteriadou KP, Remoundos MS, Katsikas MC et al The Ser‐Arg‐Tyr‐Asp region of the major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania mimics the Arg‐Gly‐Asp‐Ser cell attachment region of fibronectin. J Biol Chem 1992; 267:13980–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Becker I, Salaiza N, Aguirre M et al Leishmania lipophosphoglycan (LPG) activates NK cells through toll‐like receptor‐2. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2003; 130:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Antoine JC, Prina E, Lang T, Courret N. The biogenesis and properties of the parasitophorous vacuoles that harbor Leishmania in murine macrophages. Trends Microbiol 1998; 6:392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lodge R, Diallo TO, Descoteaux A. Leishmania donovani lipophosphoglycan blocks NADPH oxidase assembly at the phagosome membrane. Cell Microbiol 2006; 8:1922–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Toll‐dependent selection of microbial antigens for presentation by dendritic cells. Nature 2006; 440:808–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Antoine JC, Prina E, Jouanne C, Bongrand P. Parasitophorous vacuoles of Leishmania amazonensis infected macrophages maintain an acidic pH. Infect Immun 1990; 58:779–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vinet AF, Fukuda M, Turco SJ, Descoteaux A. The Leishmania donovani lipophosphoglycan excludes the vesicular proton‐ATPase from phagosomes by impairing the recruitment of synaptotagmin‐V. PLOS Pathog 2009; 5:e1000628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ramachandra L, Boom WH, Harding CV. Class II MHC antigen processing in phagosomes. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 445:353–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Houde M, Bertholet S, Gangnon E et al Phagosomes are competent organelles for antigen cross‐presentation. Nature 2003; 425:402–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McConville MJ, Mullin KA, Ilgoutz SC, Teasdale RD. Secretory pathway of Trypanosomatid parasites. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2002; 66:122–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Descoteaux A, Turco SJ. Glycoconjugates in Leishmania infectivity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999; 8:341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beverley SM, Turco SJ. Lipophosphoglycan (LPG) and the identification of virulence genes in the protozoan parasite Leishmania . Trends Microbiol 1998; 6:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Campos MA, Almeida IC, Takeuchi O et al Activation of Toll like receptor‐2 by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from a protozoan parasite. J Immunol 2001; 167:416–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kavoosi G, Ardestani SK, Kariminia A, Alimohammadian MH. Leishmania major lipophosphoglycan: discrepancy in Toll‐like receptor signaling. Exp Parasitol 2010; 124:214–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chaudhuri G, Chang KP. Acid protease activity of major surface membrane glycoprotein (gp63) from Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1988; 27:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chaudhuri G, Chaudhuri M, Pan A, Chang KP. Surface acid proteinase (gp63) of Leishmania mexicana. A metalloenzyme capable of protecting liposome encapsulated proteins form phagolysosomal degradation by macrophages. J Biol Chem 1989; 264:7483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol 2004; 16:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88‐deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 1999; 11:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. Cutting edge: TLR2‐deficient and MyD88‐deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol 2002; 165:5392–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chen L, Lei L, Chang X et al Mice deficient in MyD88 Develop a TH2‐dominant response and severe pathology in the upper genital tract following Chlamydia muridarum infection. J Immunol 2010; 184:2602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G et al MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. von Bernuth H, Picard C, Jin Z et al Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science 2008; 321:691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H et al Essential role for TIRAP in activation of the signaling cascade shared by TLR2 and TLR4. Nature 2002; 420:324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signaling specificity for Toll‐like receptors. Nature 2002; 420:329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Khor CC, Chapman SJ, Vannberg FO et al A Mal functional variant is associated with protection against invasive Pneumococcal disease, bacteremia, malaria and tuberculosis. Nat Genet 2007; 39:523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Berkley JA, Lowe BS, MwangiI et al Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zakeri S, Pirahmadi S, Mehrizi AA, Djadid ND. Genetic variation of TLR‐4, TLR‐9 and TIRAP genes in Iranian malaria patients. Malar J 2011; 10:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hawn TR, Dunstan SJ, Thwaites GE et al A polymorphism in Toll‐interleukin 1 receptor domain containing adaptor protein is associated with susceptibility to meningeal tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:1127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Oshiumi H, Okamoto M, Fujii K et al The TLR3/TICAM‐1 pathway is mandatory for innate immune responses to poliovirus infection. J Immunol 2011; 187:5320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cai S, Batra S, Shen L, Wakamatsu N, Jeyaseelan S. Both TRIF‐and MyD88‐dependent signaling contribute to host defense against pulmonary Klebsiella infection. J Immunol 2009; 183:6629–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sancho‐Shimizu V, de Diego RP, Lorenzo L et al Herpes simplex encephalitis in children with autosomal recessive and dominant TRIF deficiency. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:4889–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H et al TRAM is specifically involved in the Toll‐like receptor 4‐mediated MyD88‐independent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 2003; 4:1144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR. The structural biology of Toll‐like receptors. Structure 2011; 19:447–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lye E, Mirtsos C, Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Yeh WC. The role of interleukin 1 receptor‐ associated kinase 4 (IRAK‐4) kinase activity in IRAK‐4‐mediated signaling. J Biol Chem 2004; 270:40653–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Brown J, Wang H, Hajishengallis GN, Martin M. TLR‐signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross‐talk. J Dent Res 2011; 90:417–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xia ZP, Sun L, Chen X, Pineda G, Jiang X, Adhikari A. Direct activation of protein kinases by unanchored polyubiquitin chains. Nature 2009; 461:114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H et al Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88‐independent Toll like receptor signaling pathway. Science 2003; 301:640–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Vogel SN, Fitzgerald KA, Fenton MJ. TLRs: differential adapter utilization by Toll‐like receptors mediates TLR‐specific patterns of gene expression. Mol Interv 2003; 3:466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Oshiumi H, Matsumoto M, Funami K, Akazava T, Seya T. TICAM, an adaptor molecule that participates in Toll‐like receptor 3‐mediated interferon‐β induction. Nat Immunol 2003; 4:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Palsson‐Mcdermott EM, O'neill LA. Signal transduction by the lipopolysaccharide receptor, Toll‐like receptor‐4. Immunology 2004; 113:153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tseng PH, Matsuzawa A, Zhang W, Mino T, Vignali DA, Karin M. Different modes of ubiquitination of the adaptor TRAF3 selectively activate the expression of type I interferons and pro‐inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:70–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sasai M, Yamamoto M. Pathogen recognition receptors: ligands and signaling pathways by Toll‐like receptors. Int Rev Immunol 2013; 32:116–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ives A, Ronet C, Prevel F et al Leishmania RNA virus controls the severity of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Science 2011; 331:775–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]