Abstract

Background

Short tandem repeats (STRs) are found in many prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes, and are commonly used as genetic markers, in particular for identity and parental testing in DNA forensics. The unstable expansion of some STRs was associated with various genetic disorders (e.g., the Huntington disease), and thus was used in genetic testing for screening individuals at high risk. Traditional STR analyses were based on the PCR amplification of STR loci followed by gel electrophoresis. With the availability of massive whole genome sequencing data, it becomes practical to mine STR profiles in silico from genome sequences. Software tools such as lobSTR and STR-FM have been developed to address these demands, which are, however, built upon whole genome reads mapping tools, and thus may not be sensitive enough.

Results

In this paper, we present a standalone software tool STRScan that uses a greedy algorithm for targeted STR profiling in next-generation sequencing (NGS) data. STRScan was tested on the whole genome sequencing data from Venter genome sequencing and 1000 Genomes Project. The results showed that STRScan can profile 20% more STRs in the target set that are missed by lobSTR.

Conclusion

STRScan is particularly useful for the NGS-based targeted STR profiling, e.g., in genetic and human identity testing. STRScan is available as open-source software at http://darwin.informatics.indiana.edu/str/.

Keywords: Short tandem repeats, Whole-genome sequencing, Algorithm, DNA forensics

Background

Short tandem repeats (STRs), also referred to as the microsatellites or simple-sequence repeats (SSRs), are a short stretch of DNA containing approximately two to 30 tandemly repeated units of 1–6 bps. STRs are present in many prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes, including mammalian genomes such as human [1, 2]. Over half a million STRs are characterized in human genome, composing approximately 3% of the entire human genome [3]. Due to their high polymorphism, STRs are commonly used as genetic markers [4–7]. In particular, a small set of STR loci can be used for identity and parental testing ([8, 9]), in which multiple STR loci were amplified by using PCR in a small amount of human DNA from one (sometimes unknown) source and the length of PCR products are compared against one or more human DNA samples from the other sources (e.g., in a forensic database). This STR typing procedure has been largely standardized, and the putative STR loci subject to such test were collected in public database such as STRBase [10].

Although STRs are largely considered as “junk DNA”, some STRs locate in protein coding genes, whose products were shown to play functional roles in higher organisms, e.g., the glutamine-rich domains participating in transcription regulation [11]. Even the STRs in non-coding regions may be involved in the expression regulation of their downstream genes [12]. In particular, the unstable expansion of trinucleotide repeats were known to be associated with human diseases [13]. A preeminent example is the Huntington disease, a genetic neurodegenerative disorder caused by the expansion of a tandem repeat of CAG triplet in the Huntington (HTT) gene, resulting in a different protein form that may lead to brain degeneration [14]. As such, STR profiling in disease susceptible alleles is often used as a genetic testing tool for individuals at high risk of inheriting these genetic disorders [15].

The traditional experimental analysis of STRs involved the amplification of the target STR locus by PCR, using unique sequences in the flanking regions of the STR as primers, followed by the length measurement of the PCR product using gel electrophoresis, which indicates the copy number of the target STR. In recent years, whole genome sequencing (WGS) becomes more affordable owning to the rapid advance in next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques. Conventional software tools such as tandem repeat finder (TRF) [16] can detect novel STRs from assembled genome sequence, such as the human genome [17]. New software tools and pipelines such as lobSTR [18] and STR-FM [19] have also been developed that can be directly applied for the STR profiling in WGS data. The power of the STR analysis from NGS data has been demonstrated in a recent study, which showed that the surname of a human individual can be inferred from the personal genome sequencing data through the analysis of the profiles of Y chromosome STRs (Y-STRs) and online genealogy database [20]. The genome-wide STR profiling tools have enabled the survey of STR variations in human population [19, 21, 22]. It was also shown that a substantial number of STR loci are pervasively expressed in human population, which may represent a novel set of regulatory variants in the human genome ([23]).

In this paper, we present a standalone software tool STRScan for the profiling of STRs in next-generation sequencing (NGS) data. Here, we adopted a targeted approach to STR profiling: instead of mining all STRs at a whole genome scale (as the goal of lobSTR or STR-FM), we attempted to study only a user-defined subset of STR loci, a scenario particularly useful for forensic or genetic testing [24], and thus avoid the time-consuming genome-wide reads mapping procedure. As a result, our method is not limited by the sequence comparison against the STR loci represented as linear DNA sequences in a reference genome, and thus can adopt a fine-tuned alignment algorithm for STR identification in DNA sequences. In addition to mining whole-genome sequencing data, our method can be applied directly to STR profiling in NGS data from targeted STR samples, after STR enrichment [25], or PCR amplification of specific set of STR loci (e.g., for identity or genetic testing).

In STRScan, each STR locus is represented by a pattern including the tandem copies of one or more repetitive units, along with the upstream, downstream and the intermediate sequences between repetitive units, which can be constructed from the reference genome sequence of an organism (e.g., human), and the occurrence of each STR locus in a sequence read is identified by using a greedy seed-extension strategy. Because our goal is to profile STRs from population sequencing data (e.g., the 1000 genome sequencing data), we assume the difference between the STR pattern and its occurrence in the sequence reads are caused by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or sequencing errors, and thus composes only a small fraction of the entire locus. Therefore, STRScan used the edit distance to measure the difference between a STR pattern and its occurrence in a read, and only reports those occurrences below a small threshold (i.e., δ).

We tested STRScan on the whole genome sequencing (WGS) data from both the Sanger sequencer [26] and the Illumina sequencer (generated by the 1000 Genomes Project [27]). Comparing with existing software tools like lobSTR and STR-FM, STRScan can identify significantly (in average 20%) more STRs from NGS data, while using comparable or less computation time. Hence, STRScan is ready to be used for targeted profiling of STRs in sequencing data and for STR typing through DNA amplification followed by next-generation sequencing.

Methods

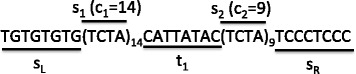

A locus of short tandem repeat (STR) is defined as a sequence of n short repeats, each consisting of a repetitive unit repeating multiple times, and spacing sequences between every two consecutive short repeats. Formally, a STR locus is represented as a pattern , in which s i and c i (i=1,2,...,n) represent the DNA string and the copy number of the i-th repetitive unit, respectively, t i represents the intermediate string between the i-th and the (i+1)-th repetitive units (and thus t n=∅), and s L and s R represent the unique strings at the upstream or downstream spanning the entire STR locus (Fig. 1). Given a DNA string Q and a STR pattern P, their distance D(Q,P)computed along an optimal alignment between them, which can be viewed as the concatenation of the alignment between each component of P and their counterpart in Q. Specifically, let (q L,q 1,p 1,...,q n,p n,q R) be a partition of the sequence Q, (i.e., Q is the concatenation of the substrings: Q=q L·q 1·p 1·...·q n·p n·q R), the distance between Q and P for this specific partition is defined as , where D(q,s) is the minimum distance (e.g., the edit distance or its variants) between the strings s and q, and (q i)m is a tandem repeat of q i in m copies (|m−n|≤ε, where ε is the maximum variants of the i-th repetitive unit) that has the smallest distance with s i. For each short read T in a given NGS dataset, our objective of STR profiling is to find if there exists a subsequence t of T, such that the minimum distance between t and P, D(t,P) is below a given threshold δ.

Fig. 1.

A schematic illustration of the pattern of a STR locus consisting of two tandem repeating units of four base-pairs long each

We used a greedy seed-extension strategy to address the STR profiling problem. We assume the difference between the STR pattern and its occurrence is so small that the occurrence contains a substring of length k that is the exact tandem copy of one repetitive unit in the STR pattern. As a result, we can index the STR patterns based on the seeds representing the tandem repeats of k bases long. For example, if a STR pattern contains a repetitive unit s i=ATCC with c i=8 copies, the pattern can be indexed by the seed of ATCCATCCATCCATCCATCC for k=20. Note that if k is not a multiple of the repetitive unit length, we can truncate the last copy of the repetitive unit in the tandem repeat: in the example above, for k=18, the seed becomes ATCCATCCATCCATCCAT. Furthermore, we also assume we can use the fitting alignment algorithm to find a substring t ′ in T with the smallest distance with a string s. In practice, we compute the edit distance between two strings using a banded dynamic programming algorithm [28] that constrains the total number of indels to be no more than a small band ω.

Built upon these two components, the STRScan algorithm takes as input a set of STR patterns and a set of NGS reads, and identifies each sequencing read containing a substring that matches one STR locus (i.e., with edit distance below δ). The algorithm consists of three steps: 1) the input set of STR patterns are indexed by k-mers of tandem repeats in the STR loci; 2) the k-mers in each read is searched against the indexed k-mers from the STR patterns, and the matched k-mers are represented as the seed alignments between corresponding reads and STR patterns; and 3) each seed alignment will be extended by using the fitting alignment algorithm. Specifically, assuming that a seed alignment between the STR pattern P and the read T with the distance D(P, T) containing m copies of the i-th repetitive unit (s i) in P and its 3’-end is aligned with the j-th nucleotide in T (if the last repetitive unit in the k-mer is truncated, we first extend the seed alignment to the end of the repetitive unit by using gap-free extension), we consider the possible extensions of the seed alignment with the minimum distance:

| 1 |

where represents the suffix of T starting at the j-th position, and s·t represents the concatenation of the two strings s and t. The alignment extension with the minimum distance is then appended into the current seed alignment, and the distance score and the end position in T are updated accordingly. The procedure is iterated until the alignment reaches the downstream sequence (s R) or the distance becomes above the threshold of δ. A similar extension algorithm can be applied to the 5’-end of the seed alignment simultaneously until it reaches the upstream sequence s L,

| 2 |

where k represents the first position in T at the 5’-end of the seed alignment, and represents the prefix of T ending at the k-th position.

Results

We tested STRScan on three whole genome sequencing (WGS) datasets: one obtained by using Sanger sequencers [26], whereas the other two obtained by using Illumina sequencers [27]. The first dataset (denoted as the Venter dataset) was downloaded from NCBI Trace Archive, consisting of about 12.5 millions of reads of 1000 bps. The other two datasets (denoted by their individual IDs, HG00145 and HG00140, respectively) were selected from the 1000 Genomes project, and downloaded from the Short Read Archive (Project ID: SRR099957 for HG00145, and ERR251013 for HG00140), consisting of 115.5 and 65.8 millions of read pairs, respectively, with each read of 100 bps long. In each of these datasets, we attempted to search for reads supporting the STRs from two different panels, which are commonly used in DNA forensics: the YSTR penal consisting of 18 STRs from human Y chromosome, and the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) panel consisting of 14 STRs from autosomes [29]. The copy number of the repeating unit in each identified targeted STR was reported by STRScan along with the supporting reads. When two or more different copy numbers are observed in the supporting reads, the corresponding STR is classified as multi-allelic: for Y chromosome STRs, the multiple alleles are likely located in different locus of Y chromosome, whereas for CODIS STRs, the multiple alleles may reflect the heterozygosity of the STR in the personal genome.

We compared the performance of STRScan and lobSTR [18] on three sets of testing data. As shown in Table 1, STRScan identified 31 reads in the Venter dataset, supporting a total of 15 out of 18 STRs in the Y chromosome STR panel, whereas lobSTR identified 20 reads supporting a total of 11 STRs. STRScan identified all STR alleles reported by lobSTR, and four additional STRs with valid supporting reads (see Supplementary website http://darwin.informatics.indiana.edu/str/ for the sequences of the supporting reads). The copy numbers reported by STRScan are in agreement with the result of lobSTR on the 11 STRs identified by both methods. Similarly, STRScan identified 34 supporting reads in the Venter dataset, supporting 12 out of 14 STRs in the CODIS panel, which contains all 9 STRs identified by lobSTR (supported by 21 reads). STRScan also outperforms lobSTR on identification of STRs in short reads obtained by using Illumina sequencers. For the two testing datasets from 1000 Genome project. For example, in the HG00140 dataset, STRScan identified 10 reads supporting 7 STRs in the Y chromosome STR panel, whereas lobSTR identified 5 reads supporting 4 STRs, and STRScan identified 12 reads supporting 7 STRs in the CODIS panel, whereas lobSTR identified 7 reads supporting 6 STRs. Similar results were obtained in the HG00145 dataset (see Table 1). Overall, STRScan identified 31 reads supporting STRs in these two datasets, whereas lobSTR identified 19 reads, with 11 reads in common.

Table 1.

Comparison of STRScan and lobSTR on STR identification from shotgun sequencing reads

| STR markers | Chromosome / location | # in reference genome | Copy number of identified STRs (number of supporting reads) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venter | HG00145 | HG00140 | ||||||

| STRScan | lobSTR | STRScan | lobSTR | STRScan | lobSTR | |||

| YSTR (on Y chromosome) panel | ||||||||

| DYS19 | chrY 9521989-9522052 | 15 | 14(1) | - | - | - | - | - |

| DYS385a | chrY 20801599-20801642 | 11 | 11(2) | 11(1) | 11(3) | - | 12(1) | - |

| chrY 20842518-20842573 | 14 | 14(1) | 14(1) | |||||

| DYS388 | chrY 14747535-14747570 | 12 | 12(2) | 12(1) | - | - | - | - |

| DYS389I | chrY 14612242-14612289 | 12 | 13(3) | 13(1) | - | - | - | - |

| DYS389II | chrY 14612242-14612405 | 29 | 29(2) | 29(2) | - | - | - | - |

| DYS390 | chrY 17274947-17275042 | 24 | 23(1) | 23(1) | 15(1) | - | - | - |

| DYS391 | chrY 14102795-14102838 | 11 | 10(1) | 10(1) | - | - | 10(2) | 10(2) |

| DYS392 | chrY 22633873-22633911 | 13 | 13(2) | 13(2) | - | - | ||

| DYS393 | chrY 3131152-3131199 | 12 | 13(2) | - | - | - | - | - |

| DYS426 | chrY 19134850-19134885 | 12 | 12(1) | 12(1) | - | - | - | - |

| DYS437 | chrY 14466994-14467057 | 16 | - | - | - | - | 16(2) | - |

| DYS438 | chrY 14937824-14937873 | 10 | 12(1) | 12(1) | - | - | 10(1) | 10(1) |

| DYS439 | chrY 14515312-14515363 | 13 | 12(1) | 12(1) | - | - | 11(1) | 11(1) |

| DYS447 | chrY 15278740-15278854 | 23 | 25(1) | - | - | - | - | - |

| DYS448 | chrY 24365070-24365225 | 19 | - | - | - | - | - | 8(1) |

| DYS460 (A7.1) | chrY 21050842-21050881 | 10 | 12(2) | - | - | - | 11(1) | - |

| H4 | chrY 18743553-18743600 | 12 | - | - | 12(1) | 12(1) | 11(2) | - |

| YCAIIa | chrY 19622111-19622156 | 23, 23 | 19(3), 23(5) | 19(3), 23(4) | 19(1) | 19(2) | - | - |

| Total | 18 | 15(31) | 11(20) | 4(6) | 2(3) | 7(10) | 4(5) | |

| CODIS (on autosomes) panel | ||||||||

| CSF1PO | chr5 149455887-149455938 | 13 | 11(7) | 11(5) | - | - | 11(1) | 11(1) |

| D13S317a | chr13 82722160-82722203 | 11 | 12(1),13(2) | 11(1) | - | - | - | - |

| D16S539 | chr16 86386308-86386351 | 11 | 12(2) | - | 13(1) | - | 11(2) | 11(1) |

| D18S51 | chr18 60948900-60948971 | 18 | 14(2) | 14(2) | - | - | 15(1) | - |

| D21S11 | chr21 20554291-20554417 | 29 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| D3S1358a | chr3 45582231-45582294 | 16 | 16(3) | 16(3) | - | - | - | - |

| D5S818 | chr5 123111250-123111293 | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| D7S820 | chr7 83789542-83789593 | 13 | 10(3) | 10(2) | - | - | 8(3) | - |

| D8S1179 | chr8 125907107-125907158 | 13 | 12(1) | 12(1) | 8(1) | 6(2) | - | 13(1) |

| FGAa | chr4 155508888-155508975 | 22 | 26(1), 21(1) | 26(1), 21(1) | - | - | - | - |

| PentaD | chr21 45056086-45056150 | 13 | 13(2) | - | 9(1) | 9(1) | - | - |

| PentaE | chr15 97374245-97374269 | 5 | 12(2) | 12(1) | - | - | 13(1) | 13(1) |

| TH01 | chr11 2192318-2192345 | 7 | 6(2) | - | - | - | 5(1),10(2) | 10(2) |

| TPOX | chr2 1493425-1493456 | 8 | 8(5) | 8(4) | - | - | 8(1) | 8(1) |

| Total | 14 | 12(34) | 9(21) | 3(3) | 2(4) | 7(12) | 6(7) | |

aMulti-allelic STR markers, each with two alleles on the reference human genome

Discussion

Our results showed that short reads obtained from conventional next-generation sequencing techniques (e.g., Illumina sequencers for whole genome sequencing) may not be suitable for targeted profiling of STRs: only a small number of reads can be identified supporting common STR panels (such as Y Chromosome and CODIS) in whole genome sequencing data. On the other hand, relatively longer reads from Illumina miSeq, which may reach the length of 500–600 bps, comparable to the length of Sanger sequencing reads as in Venter genome datasets, are much more sensitive for targeted STR profiling (as shown in Table 1). When combined with targeted amplification of specific STR loci, miSeq sequencing may achieve satisfactory sensitivity for STR typing in DNA forensics and for targeted STR profiling in genetic disease screening. In the future, we plan to test the performance of STRScan on more forensic sequencing datasets when they become publicly available.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present STRScan, which allows the targeted search of an user-defined panel of short tandem repeats (STRs) in whole-genome sequencing data. Comparing to existing tools (such as lobSRT) designed for blind genome-wide mining, STRScan showed improved sensitivity on identifying sequencing reads supporting STRs with various copy numbers at specific loci, as it employs a fast greedy algorithm to compare the read sequence and putative STRs.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Dr. Kazufusa Okamoto for helpful discussions.

Funding

This research and this article’s publication costs were supported by National Science Foundation (Grant no: DBI-1262588). The funding agency did not play any role in the design or conclusion of our study.

Availability of data and materials

STRScan is available as open-source software at http://darwin.informatics.indiana.edu/str/.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Bioinformatics Volume 18 Supplement 11, 2017: Selected articles from the International Conference on Intelligent Biology and Medicine (ICIBM) 2016: bioinformatics. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcbioinformatics.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-18-supplement-11.

Abbreviations

- CODIS

Combined DNA Index System

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphsim

- SSR

Simple-sequence repeats

- STR

Short tandem repeats

- WGS

Whole-genome sequencing

Authors’ contributions

HT conceived the study and developed the software. EN conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. HT and EN wrote the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Haixu Tang, Email: hatang@indiana.edu.

Etienne Nzabarushimana, Email: enzabaru@indiana.edu.

References

- 1.Powell W, Machray GC, Provan J. Polymorphism revealed by simple sequence repeats. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1(7):215–22. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(96)86898-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tóth G, Gáspári Z, Jurka J. Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res. 2000;10(7):967–81. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura Y, Leppert M, O’Connell P, Wolff R, Holm T, Culver M, Martin C, Fujimoto E, Hoff M, Kumlin E, et al. Variable number of tandem repeat (vntr) markers for human gene mapping. Science. 1987;235(4796):1616–22. doi: 10.1126/science.3029872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards A, Hammond HA, Jin L, Caskey CT, Chakraborty R. Genetic variation at five trimeric and tetrameric tandem repeat loci in four human population groups. Genomics. 1992;12(2):241–53. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90371-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dib C, Fauré S, Fizames C, Samson D, Drouot N, Vignal A, Millasseau P, Marc S, Kazan J, Seboun E, et al. A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome based on 5,264 microsatellites. Nature. 1996;380(6570):152–4. doi: 10.1038/380152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masters JR, Thomson JA, Daly-Burns B, Reid YA, Dirks WG, Packer P, Toji LH, Ohno T, Tanabe H, Arlett CF, et al. Short tandem repeat profiling provides an international reference standard for human cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(14):8012–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121616198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler JM, et al. Short tandem repeat typing technologies used in human identity testing. Biotechniques. 2007;43(4):2–5. doi: 10.2144/000112582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayser M, Sajantila A. Mutations at Y-STR loci: implications for paternity testing and forensic analysis. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;118(2):116–21. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruitberg CM, Reeder DJ, Butler JM. STRBase: a short tandem repeat dna database for the human identity testing community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):320–2. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escher D, Bodmer-Glavas M, Barberis A, Schaffner W. Conservation of glutamine-rich transactivation function between yeast and humans. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(8):2774–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.8.2774-2782.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contente A, Dittmer A, Koch MC, Roth J, Dobbelstein M. A polymorphic microsatellite that mediates induction of pig3 by p53. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):315–20. doi: 10.1038/ng836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatchel JR, Zoghbi HY. Diseases of unstable repeat expansion: mechanisms and common principles. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(10):743–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker FO. Huntington’s disease. The Lancet. 2007;369(9557):218–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers RH. Huntington’s disease genetics. NeuroRx. 2004;1(2):255–62. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze dna sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelfand Y, Rodriguez A, Benson G. TRDB: the tandem repeats database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl 1):80–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gymrek M, Golan D, Rosset S, Erlich Y. lobSTR: a short tandem repeat profiler for personal genomes. Genome Res. 2012;22(6):1154–62. doi: 10.1101/gr.135780.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fungtammasan A, Ananda G, Hile S, Su M, Sun C, Harris R, Medvedev P, Eckert K, Makova K. Accurate typing of short tandem repeats from genome-wide sequencing data and its applications. Genome Res. 2015;25(5):736–49. doi: 10.1101/gr.185892.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gymrek M, McGuire AL, Golan D, Halperin E, Erlich Y. Identifying personal genomes by surname inference. Science. 2013;339(6117):321–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1229566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willems T, Gymrek M, Highnam G, Mittelman D, Erlich Y, Consortium GP, et al. The landscape of human STR variation. Genome Res. 2014;24(11):1894–904. doi: 10.1101/gr.177774.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duitama J, Zablotskaya A, Gemayel R, Jansen A, Belet S, Vermeesch JR, Verstrepen KJ, Froyen G. Large-scale analysis of tandem repeat variability in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(9):5728–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gymrek M, Willems T, Zeng H, Markus B, Daly MJ, Price AL, Pritchard J, Erlich Y. Abundant contribution of short tandem repeats to gene expression variation in humans. bioRxiv; 2015:017459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Scheible M, Loreille O, Just R, Irwin J. Short tandem repeat typing on the 454 platform: strategies and considerations for targeted sequencing of common forensic markers. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2014;12:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlson KD, Sudmant PH, Press MO, Eichler EE, Shendure J, Queitsch C. MIPSTR: a method for multiplex genotyping of germline and somatic STR variation across many individuals. Genome Res. 2015;25(5):750–61. doi: 10.1101/gr.182212.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL, Walenz BP, Axelrod N, Huang J, Kirkness EF, Denisov G, et al. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(10):254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Consortium GP, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chao KM, Pearson WR, Miller W. Aligning two sequences within a specified diagonal band. Comput Appl Biosci CABIOS. 1992;8(5):481–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler JM. Genetics and genomics of core short tandem repeat loci used in human identity testing. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51(2):253–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

STRScan is available as open-source software at http://darwin.informatics.indiana.edu/str/.