Abstract

Introduction

Frail patients have decreased physiological reserves and consequently, they are unable to recover as quickly from surgery. Frailty, as an entity, is a risk factor of increased morbidity and mortality. It is also associated with a longer time to discharge. This trial is undertaken to determine if a novel prehabilitation protocol (10-day bundle of interventions—physiotherapy, nutritional supplementation and cognitive training) can reduce the postoperative length of stay of frail patients who are undergoing elective abdominal surgery, compared with standard care.

Methods and analysis

This is a prospective, single-centre, randomised controlled trial with two parallel arms. 62 patients who are frail and undergoing elective abdominal surgery will be recruited and randomised to receive either a novel prehabilitation protocol or standard care. Participants will receive telephone reminders preoperatively to encourage protocol compliance. Data will be collected for up to 30 days postoperatively. The primary outcome of the trial will be the postoperative length of stay and the secondary outcomes are the postoperative complications and functional recovery during the hospital admission.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Singapore General Hospital Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2016/2584). The study is also listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (Trial number: NCT02921932). All participants will sign an informed consent form before randomisation and translators will be made available to non-English speaking patients. The results of this study will be published in peer-reviewed journals as well as national and international conferences. The data collected will also be made available in a public data repository.

Trial registration number

NCT02921932 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Keywords: Frailty, Prehabilitation, Protocol

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This is a novel intervention looking at reducing hospital length of stay for frail elderly patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

Randomised controlled trial design minimises risk of selection bias.

Pragmatic trial design allows understanding if the intervention will work in the real world.

Single-centre study design may limit the generalisability of the study.

Open-label study design may result in bias, although the use of objective outcome measures and minimising the interaction between the research and treatment teams limit this bias.

Introduction

Frailty is defined as a state of decline and vulnerability, characterised by weakness and a decrease in physiological reserve.1 Consequently, frail patients are unable to recover as quickly from a stressful event such as an illness or surgery.1 It is common in the elderly and is thought to be due to an age-related decline in multiple organ systems.2 However, it is also increasingly recognised as an important prognostic factor inpatients with chronic diseases.3–6 Consequently, it has been demonstrated that frailty is associated with a significantly increased odds of postoperative mortality (OR 1.33–46.33) and morbidity (OR 1.24–3.36).7 Patients who are frail also spend a longer time (median of 2.5 days longer) in hospital compared with fit patients, increasing healthcare costs and resource consumption.8

The population is ageing rapidly worldwide. In 2004, 461 million people in the world were above the age of 65. By 2050, it is estimated that 2 billion people will be above the age of 65.9 10 As such, it may be anticipated that a large number of frail patients will be requiring surgery in the future. Currently, there is no clear intervention that has been shown to modify the syndrome or its impact on postoperative outcomes. Therefore, it is important to clinician-researchers to develop strategies aimed at improving the outcomes of this high-risk population undergoing surgery.

Background

It has been recognised that frailty is a dynamic process. A prospective observational study of 754 community-living elderly subjects by Gill et al showed that over a 18-month period, 43% participants became more frail while 23% became less frail.11 In the non-surgical population, it has been demonstrated that frailty can be modified through interventions such as exercise therapy, dietary interventions and drug therapy.12–14

After major surgery, there is an immediate and substantial decline in a patient's functional status, followed by recovery in the postoperative period.15 16 While a fit individual is likely to regain his pre-hospitalisation level of functioning, a frail individual may not be able to respond as well, resulting in delayed recovery, increased hospital length of stay and operative mortality.15 17 There is initial evidence that prehabilitation may be used to reduce morbidity and mortality in frail patients. Notably, Harari et al found that the introduction of a comprehensive geriatric assessment service resulted in a clinically significant decrease in medical complications and hospital length of stay.18 However, at present, most recent guidelines are unable to conclusively support the use of prehabilitation as standard practice.19

The primary objective of the study is to determine if prehabilitation with a bundle of interventions (physiotherapy, nutritional support and cognitive exercises) initiated preoperatively in frail patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery will result in shorter hospital length of stay. The secondary objectives are to determine if prehabilitation will decrease postoperative complications and improve functional recovery following surgery.

Frailty is a condition that affects multiple organ systems.20 As such, the use of a combination of interventions is likely to yield better results than a single intervention. For this reason, the intervention in this study consists of a bundle of interventions rather than a single intervention. Sarcopenia, anorexia and exhaustion are key features of frailty.20 Current understanding of frailty is that it is a modifiable syndrome.11 As such, physiotherapy (inspiratory muscle training (IMT)) and nutritional supplementation may be able to modify the syndrome preoperatively and improve postoperative outcomes.21–26 Postoperative delirium is also common in frail patients and may result in delayed discharge from hospital.27 Prior studies have demonstrated that cognitive training may have a positive impact on postoperative delirium.28 Therefore, cognitive training is also included in the prehabilitation bundle.

IMT and aerobic exercise training are the most common physiotherapy interventions used to optimise patients preoperatively.29 At present, there are no head-to-head studies that compare the effects of IMT and aerobic training. A Cochrane article published in 2015 examined whether IMT had an impact on the recovery of adults after surgery and concluded that compared with usual care, preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction in postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia. It also resulted in a reduced hospital length of stay. In comparison, studies on aerobic exercise training have yield mixed results.30–33 For this reason, IMT was chosen over aerobic exercise training as the physiotherapy intervention in our prehabilitation bundle.

Methods: participants, interventions and outcomes

Study design

This trial is a prospective, randomised controlled trial conducted at a tertiary hospital in Singapore (Singapore General Hospital (SGH)).

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged 65 years who are diagnosed as frail (Fried Criteria Score of 3 or more) are enrolled in the study if they are seen at least 11 days prior to their elective major abdominal surgery and are able to understand and follow the prescribed cognitive and physical exercises. The definition of a major abdominal surgery is defined as an intraperitoneal surgery with an expected length of stay of more than 2 days. If the patients attend the clinic more than 11 days prior to the surgery date, they will be informed to start their prehabilitation bundle 11 days prior to the surgery.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with Parkinson's disease, previous strokes, neuromuscular disorders and those taking carbidopa, levodopa, donepezil hydrochloride or antidepressants are excluded as previous studies have found that these medications can cause symptoms that are similar to the frailty domains.20 Patients who are unable to communicate are also excluded.

Control

In the control arm, patients will be given standard education material regarding their surgery. They are then asked to carry out their daily activities as usual until the admission of the surgery. This will be conducted, as the norm, by nurses from the surgical clinic, who are not involved with the study.

Intervention

In the intervention arm, patients will be given an Inspiratory Muscle Trainer device and taught to use it twice daily, based on the physiotherapy protocol (online supplementary appendix A). A nutritional assessment will also be done in accordance with the nutrition protocol (online supplementary appendix B and if needed, nutrition supplement will be prescribed. A cognitive exercise (online supplementary appendix C in the form of a memory training card game, will be taught to the patients and the caregiver (if available), and the patient will be instructed to play it two times per day. The physiotherapy, nutrition and cognitive interventions will be performed by a physiotherapist, dietician and research assistant, who are involved with the study.

bmjopen-2017-016815supp001.pdf (89.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016815supp002.pdf (499.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016815supp003.pdf (55.7KB, pdf)

This intervention will be run for a period of 10 days. Currently, there is no consensus about the duration of prehabilitation that is required for optimising surgical patients. In previous studies, this period ranged from 2 to 4 weeks.21 22 However, we hypothesise that by combining a number of interventions into a bundle, we may be able to achieve beneficial effects within a shorter time frame. Furthermore, in our centre, the majority of patients were listed within 14 days to the date of their surgery. Considering that it may take up to 3 days for the patient to be seen at the preoperative evaluation clinic, be enrolled in the study and be given the intervention, we considered a prehabilitation period of 10 days to be both practical and feasible.

The patients will be provided with a protocol activities log (online supplementary appendix D)and a study assistant will conduct a telephone conversation on days 1, 3 and 7 to encourage compliance to the protocol and answer any queries with regards to the study.

bmjopen-2017-016815supp004.pdf (434.6KB, pdf)

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the postoperative length of stay (POLOS).

The secondary outcomes are postoperative complications and functional recovery during the hospital admission for up to 30 days. The postoperative complications that are recorded including mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, reintubation, ventilation days in ICU, acute myocardial infarction and new arrhythmias. For functional recovery, the postoperative quality of recovery scale (PQRS) questionnaire34 is administered at four time points (day of surgery, postoperative days 1, 3 and 7) throughout their surgical admission.

Participant timeline

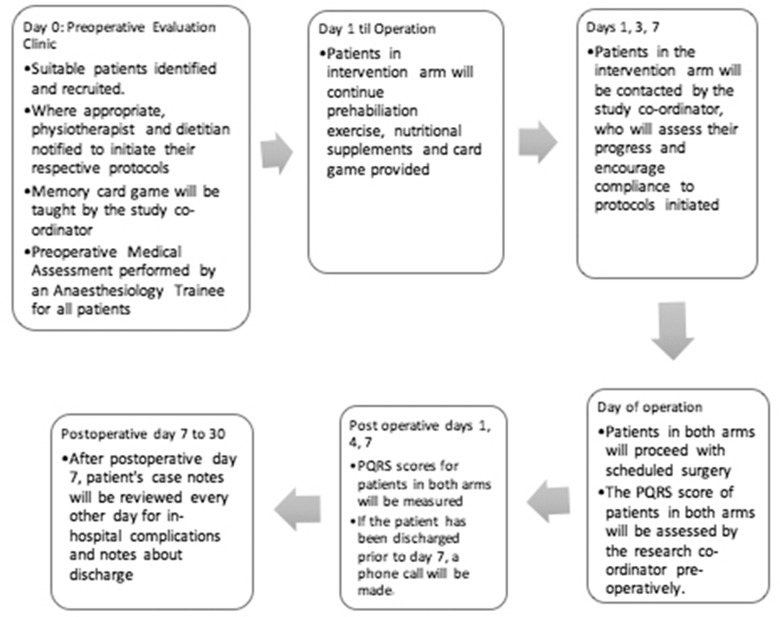

This trial comprises a 10-day intervention treatment phase and a 7-day postoperative follow-up phase. Patients may drop out of the trial at any point in time. The patients’ baseline function will be measured at recruitment, immediately preoperatively and on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7. They will then be released from the study on postoperative day 30. (figure 1)

Figure 1.

Participant timeline. PQRS, postoperative quality of recovery scale.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the POLOS. A recent study from our centre found that frail patients had a longer median POLOS compared with non-frail patients—13.5 days compared with 8 days. As such, we considered an absolute reduction of 2 days of POLOS to be clinically significant.35 Due to non-parametric distribution of the POLOS, we used the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test to estimate the sample size. Using a type I error of 0.05 and power of 80%, the sample size needed was 56. To account for a 10% dropout rate, a total recruitment size of 62 participants was obtained. As this sample size was calculated for the primary outcome measure, any conclusion derived from the secondary outcome measures may be underpowered and may require further studies.

Recruitment

Potential participants will be identified from the appointment list for attendees of the preoperative evaluation clinic at SGH. On registration, patients about 65 years old and listed for abdominal surgery will be approached and given the opportunity to fill up the frailty questionnaire based on Fried's criteria.20 If they are diagnosed as frail (Fried score ≥3), they will be invited to take part in the study. Written informed consent will then be taken from participants who are willing to be enrolled into the study.

Methods: assignment of interventions

Randomisation and allocation concealment

On enrolment, patients will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention or control arm of the study. The randomisation will be done via a computer-generated list. The allocation will be concealed in an opaque envelope by a study assistant who is blinded to the subsequent allotment.

Blinding

The investigators will not be blinded as they will be prescribing the intervention bundle in the intervention arm. However, hospital staff, including nurses and surgeons, will be blinded to the study arm that the patient has been assigned to. However, we note that it may be difficult for the treating team to remain fully blinded in the days postoperative as the study details may be disclosed by the unblinded participants.

Methods: data collection, management and analysis

Data collection

On the day of the operation, the patient's recovery from surgery will be assessed using the PQRS scale prior to his discharge from the Post-Anaesthetic Care Unit. The PQRS scale will be repeated on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7. If the patient is discharged prior to day 7, the PQRS assessment will be performed via the telephone. Apart from that, a research assistant will be assigned the role of reviewing the patients’ clinical records for a list of complications every other day until the patient is discharged or up to 30 days postoperatively.

The participants are allowed to withdraw their participation from the study at any time. Demographic information of eligible patients who decline to participate and patients who withdraw their consents after randomisation will also be collected in order to assess the feasibility and take-up rate of the bundled interventions. While the patients do not need a valid justification for withdrawing from the study, the reasons for their withdrawal will be recorded. This data will also be used to examine whether there are any systematic differences between those who have declined and those who stayed on in the study.

Electronic and paper records of the patients will be used to obtain information about the patients’ demographics, procedure urgency, intraoperative procedure and anaesthetic variables, blood product utilisation, mechanical ventilation, delirium/coma, ICU and hospital LOS, major adverse events and infections.

Data management

Confidentiality of participant data will be maintained at all times during the study. Each patient will be identified with a unique study-related identification number. Their personal details for each participant are kept securely in an access-controlled, locked cabinet at the investigation centre. The study-related identification number is used on the case report form (CRF).

Local research staff are responsible for entry of de-identified information into the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tool hosted on a secure server at Singapore General Hospital.36 Like the patient details, all hard copies of the research data will be kept in the access-controlled, locked cabinet at the investigation centre. Soft copies of the research data are kept on a password-protected computer. Only the study members will have access to the data.

Records for all participants, including CRFs, all source documentation (containing evidence to study eligibility, history and physical findings, laboratory data, results of consultations, etc.) as well as IRB records and other regulatory documentation will be retained by the principle investigator and be accessible for inspection and copying by authorised authorities. Compliant to the Singhealth Institutional Review Board policy, research data will be kept in the Department of Anaesthesiology in Singapore General Hospital for 6 years before being destroyed.

Quality control and quality assurance

All data will be monitored and reviewed by the PI or co-investigators. Training will be provided to the research coordinator and the data entry of all the case report forms will be verified by a second person from the study team.

Statistical method

In this randomised controlled trial, an intention-to-treat analysis will be performed.

The primary outcome of this study is postoperative length of stay. If the primary outcome is normally distributed, the results will be described using means (with SD and CIs) and analysed using the Student's t-test. However, if the primary outcome is not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test will be performed.

For the secondary outcomes, binary measures such as mortality, ICU admission, reintubation, acute myocardial infarction and new arrhythmias, the risk ratios and risk differences and their 95% CIs will be estimated using binomial regression. Quality of recovery from surgery will be measure by the PQRS score. The PQRS consists of five recovery domains (physiologic, emotive, nociceptive, activities of daily living, and cognition), and one self-assessment domain, including satisfaction. Pain scores are measures using a visual faces chart with a 1 to 5 scale, with scores of 3 or greater representing moderate to severe pain. Data will be reported as the proportion of patients recovered at each time point. Differences between groups over days 1 to 7 will be analysed using the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel test. Continuous data such as the days of ICU stay and ventilation days will be analysed using Student's t-test.

To ascertain the robustness of the test results, a per protocol analysis for the primary outcome, based on 75% compliance from the activity log, will be done. We will also perform the analysis with and without adjustment for baseline characteristics. Statistical comparisons across the intervention and control arms will be performed for patient demographics (age group and race), duration of surgery, site of surgery (upper vs lower abdominal), smoking status, presence of malignancy, use of regional anaesthesia and blood product utilisation. If there are differences between the intervention and control arms, multivariate models will be performed to adjust for these baseline differences.

Statistical significance will be considered when the p value is≤0.05.

Methods: monitoring

The data and safety monitoring will be performed by the Principal Investigator (PI) and Co-investigators. The practices are also subjected to audit and monitoring by the Division of Research at SGH as well as the Centralised Institutional Review Board. There will also be monthly reviews of the adverse events and dropouts.

The management of adverse events will be based on Singhealth CIRB guidelines. Adverse events will be reported by the PI to the CIRB within the stipulated timeframe. The PI will also be responsible for informing the institutional representative and sponsor. There is no independent data safety and monitoring board made for this study due to the anticipated low risk nature of the intervention. Data safety and monitoring will be done by the study team, reported to CIRB and the study sponsor. There are no plans for interim analyses due to the relatively low sample size and anticipated rapid recruitment rate.

Ethics

This study will be conducted in accordance with the Singapore Good Clinical Practice (SGCP) guidelines, which is based on the principles enshrined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study has been approved by the Singapore General Hospital Institutional Review Board (SGH IRB) (CIRB Ref: 2016/2584) and is registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov registry (Identified: NCT02921932). In the event of any important protocol modifications, all investigators, SGH IRB and trial participants will be notified. The results of this study will be presented at international conferences and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. The data collected will also be made available in a public data repository.

All eligible participants will be approached by the research assistant during their visit to the preoperative evaluation clinic. They will be given an explanation about the study, a patient information sheet and a consent form. They will then be given an ample time to consider if they would like to participate in the study. They will also be allowed to ask questions freely. If the participant expresses an interest to participate in the study, a written consent will be obtained. The consent forms are in English. However, participants from non-English speaking backgrounds will be provided a translator. For illiterate participants, an accompanying family member will be approached to verify and witness the consent process.

Conclusion

In this protocol, we describe our randomised controlled trial looking at the impact of a novel prehabilitation bundle on a frail patient's postoperative length of stay. This study also examines the secondary outcome measures of functional recovery and in-hospital complications. The strengths of this study are that it is novel, randomised-controlled trial design and uses cheap and easily available interventions to decrease hospital length of stay. If this bundle is successful in reducing a frail patient's POLOS, it will have significant impact as it will decrease resource use and free up resources for other patients.

The limitations of this study are its single-centre and open-label design. In order to ameliorate these limitations, care was taken to ensure that the researchers do not have any role to play in the determining the patients’ POLOS. The study team will have very limited or no contact with the clinical team, therefore, minimising the risk that a treating physician's knowledge of the patient's group assignment will lead to a bias in decision making. In addition, the secondary outcomes were objectively defined to minimise subjectivity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HRA: designed and conceptualised study, prepared draft manuscript, revised draft manuscript, approved final manuscript for submission, statistical calculations. VPX, HKO, PLE,SAK: designed and conceptualised study, revised draft manuscript, approved final manuscript for submission. YH: designed and conceptualised study, revised draft manuscript, approved final manuscript for submission, statistical calculations. CWL: designed and conceptualised study, prepared draft manuscript, revised draft manuscript, approved final manuscript for submission. All the authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This trial is supported by the Singhealth Foundation Transition Project Grant (SHF/HSRAg002/2015). Thes funding source, Singhealth Foundation, has no role in the design of this study and will not have a role in the analysis and interpretation of the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Consent of the participants will be obtained.

Ethics approval: Singhealth Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. . Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aunan JR, Watson MM, Hagland HR, et al. . Molecular and biological hallmarks of ageing. Br J Surg 2016;103:e29–e46. 10.1002/bjs.10053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Green P, Arnold SV, Cohen DJ, et al. . Relation of frailty to outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (from the PARTNER trial). Am J Cardiol 2015;116:264–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. . Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:896–901. 10.1111/jgs.12266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. The Prognostic importance of Frailty in Cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2538–43. 10.1111/jgs.13819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guaraldi G, Brothers TD, Zona S, et al. . A frailty index predicts survival and incident multimorbidity independent of markers of HIV disease severity. AIDS 2015;29:1633–41. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, et al. . Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J Surg Res 2013;183:104–10. 10.1016/j.jss.2013.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan SA, Chua HW, Hirubalan P, et al. . Association between frailty, cerebral oxygenation and adverse post-operative outcomes in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: an observational pilot study. Indian J Anaesth 2016;60:102–7. 10.4103/0019-5049.176278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kinsella KPD. Global aging: the challenge of success. Population Bulletin. Washington: Population Reference Bureau, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nations U. The World at six billion, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, et al. . Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:418–23. 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cranney A. Is there a new role for angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in elderly patients? Can Med Assoc J 2007;177:891–2. 10.1503/cmaj.071062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodnough LT, Maniatis A, Earnshaw P, et al. . Detection, evaluation, and management of preoperative anaemia in the elective orthopaedic surgical patient: nata guidelines. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:13–22. 10.1093/bja/aeq361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Theou O, Stathokostas L, Roland KP, et al. . The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res 2011;2011:1–19. 10.4061/2011/569194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown CJ, Roth DL, Allman RM, et al. . Trajectories of life-space mobility after hospitalization. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:372–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Topp R, Ditmyer M, King K, et al. . The effect of bed rest and potential of prehabilitation on patients in the intensive care unit. AACN Clin Issues 2002;13:263–76. 10.1097/00044067-200205000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoogeboom TJ, Dronkers JJ, Hulzebos EH, et al. . Merits of exercise therapy before and after major surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2014;27:161–6. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harari D, Hopper A, Dhesi J, et al. . Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery ('POPS'): designing, embedding, evaluating and funding a comprehensive geriatric assessment service for older elective surgical patients. Age Ageing 2007;36:190–6. 10.1093/ageing/afl163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beech F, Brown A, et al. . Peri-operative care of the elderly 2014. Anaesthesia 2014;69:81–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M157. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dronkers J, Veldman A, Hoberg E, et al. . Prevention of pulmonary complications after upper abdominal surgery by preoperative intensive inspiratory muscle training: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil 2008;22:134–42. 10.1177/0269215507081574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hulzebos EH, Helders PJ, Favié NJ, et al. . Preoperative intensive inspiratory muscle training to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications in high-risk patients undergoing CABG surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006;296:1851–7. 10.1001/jama.296.15.1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agrelli TF, de Carvalho Ramos M, Guglielminetti R, et al. . Preoperative ambulatory inspiratory muscle training in patients undergoing esophagectomy. A pilot study. Int Surg 2012;97:198–202. 10.9738/CC136.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, et al. . American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1390–413. 10.1164/rccm.200508-1211ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tieland M, Dirks ML, van der Zwaluw N, et al. . Protein supplementation increases muscle mass gain during prolonged resistance-type exercise training in frail elderly people: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:713–9. 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muscaritoli M, Krznaric Z, Barazzoni R, et al. . Effectiveness and efficacy of nutritional therapy - A cochrane systematic review. Clin Nutr 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kistler EA, Nicholas JA, Kates SL, et al. . Frailty and Short-Term Outcomes in patients with hip fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2015;6:209–14. 10.1177/2151458515591170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saleh AJ, Tang GX, Hadi SM, et al. . Preoperative cognitive intervention reduces cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients after gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Monit 2015;21:798–805. 10.12659/MSM.893359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cabilan CJ, Hines S, Munday J. The effectiveness of prehabilitation or preoperative exercise for surgical patients: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2015;13:146–87. 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim DJ, Mayo NE, Carli F, et al. . Responsive measures to prehabilitation in patients undergoing bowel resection surgery. Tohoku J Exp Med 2009;217:109–15. 10.1620/tjem.217.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dronkers JJ, Lamberts H, Reutelingsperger IM, et al. . Preoperative therapeutic programme for elderly patients scheduled for elective abdominal oncological surgery: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil 2010;24:614–22. 10.1177/0269215509358941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carli F, Charlebois P, Stein B, et al. . Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2010;97:1187–97. 10.1002/bjs.7102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soares SM, Nucci LB, da Silva MM, et al. . Pulmonary function and physical performance outcomes with preoperative physical therapy in upper abdominal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:616–27. 10.1177/0269215512471063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Royse CF, Newman S, Chung F, et al. . Development and feasibility of a scale to assess postoperative recovery: the post-operative quality recovery scale. Anesthesiology 2010;113:892–905. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d960a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khan SA, Chua HW, Hirubalan P, et al. . Association between frailty, cerebral oxygenation and adverse post-operative outcomes in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: an observational pilot study. Indian J Anaesth 2016;60:102–7. 10.4103/0019-5049.176278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016815supp001.pdf (89.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016815supp002.pdf (499.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016815supp003.pdf (55.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016815supp004.pdf (434.6KB, pdf)