Abstract

Introduction

Frailty is one of the most challenging aspects of population ageing due to its association with increased risk of poor health outcomes and quality of life. General practice provides an ideal setting for the prevention and management of frailty via the implementation of preventive measures such as early identification through screening.

Methods and analysis

Our study will evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and diagnostic test accuracy of several screening instruments in diagnosing frailty among community-dwelling Australians aged 75+ years who have recently made an appointment to see their general practitioner (GP). We will recruit 240 participants across 2 general practice sites within South Australia. We will invite eligible patients to participate and consent to the study via mail. Consenting participants will attend a screening appointment to undertake the index tests: 2 self-reported (Reported Edmonton Frail Scale and Kihon Checklist) and 5 (Frail Scale, Groningen Frailty Index, Program on Research for Integrating Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy (PRISMA-7), Edmonton Frail Scale and Gait Speed Test) administered by a practice nurse (a Registered Nurse working in general practice). We will randomise test order to reduce bias. Psychosocial measures will also be collected via questionnaire at the appointment. A blinded researcher will then administer two reference standards (the Frailty Phenotype and Adelaide Frailty Index). We will determine frailty by a cut-point of 3 of 5 criteria for the Phenotype and 9 of 42 items for the AFI. We will determine accuracy by analysis of sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios. We will assess feasibility and acceptability by: 1) collecting data about the instruments prior to collection; 2) interviewing screeners after data collection; 3) conducting a pilot survey with a 10% sample of participants.

Ethics and dissemination

The Torrens University Higher Research Ethics Committee has approved this study. We will disseminate findings via publication in peer-reviewed journals and presentation at relevant conferences.

Keywords: frailty, general practice, older people, diagnostic test accuracy, feasibility, sensitivity and specificity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is among the first reported studies on frailty screening within the Australian general practice context.

Our inclusion of feasibility and acceptability measures along with diagnostic test accuracy will strengthen the relevance of our study for policy and practice.

The acceptability component of our study will measure acceptability of screening instruments to both health service providers (general practitioners and practice nurses) and consumers.

This phase of the study will be limited to two general practice sites.

The study will test only a subset of the full set of frailty screening instruments in international use due to inappropriateness for Australian context, excessive length or other exclusion criteria.

Introduction

Background

Population ageing is proceeding at an unprecedented pace throughout the world,1 with frailty among its most challenging manifestations.2 3 Frailty is associated with decreased quality of life,4–6 disability,4 5 7 8 increased healthcare utilisation,4 5 7 9 falls,9 10 institutionalisation9 11 and death.7 9 12 Despite the importance of frailty, there is currently no consensus regarding its prevalence.13 One estimate based on a systematic review suggests a weighted average prevalence of 10.7% among community-dwelling persons aged 65+ years, although results vary widely.13 Applying even this conservative rate to the future Australian population aged 65+ years would result in a projection of over 1 million frail Australians by 2061,14 a significant challenge for the healthcare system.

Geriatricians have traditionally provided specialist care for the frail. However, population ageing and the need for early identification, prevention and reversal of frailty highlights an increasing role for general practitioners (GPs) and healthcare teams in community settings as this population grows.15–17 Despite research advances, frailty research in primary care remains a ‘topic in its infancy’.16 Consequently, a growing number of studies have addressed the development and validation of frailty screening instruments in general practice settings—an issue especially relevant in Australia, where research on this topic has been limited.18 However, there remains much controversy over the validity and reliability of the instruments,19 20 leading to calls for more validation to be conducted across diverse populations. Furthermore, there remains extensive disagreement among the experts over how extensive screening should be.21–23 Regardless of the extent of screening, GPs and their teams will need accurate screening instruments to effectively identify those who are frail or at risk,24 25 and if translation into busy practices is to be successful, also instruments that are logistically feasible and acceptable to health service providers and consumers.

Australian care context and purpose for screening

In Australia, opportunities for comprehensive assessment for older people in general practice through the 75+ Health Assessment and associated care planning receive government rebates under the Medical Benefits Scheme (MBS).26 Through chronic disease and management health plans, older people can then access rebated allied health (although limited) and psychology services. GPs are also able to refer to specialist geriatricians for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) for which also there is a specialist rebate. Access to medical services might vary by geographical region.

Means tested but publicly funded Aged Care Services that provide for home case support services and some therapy services are accessible through the centralised portal, My Aged Care. A brief assessment of multiple domains is undertaken but where care needs are identified as high, a more comprehensive assessment occurs through the Aged Care Assessment Programme. The older person might then be approved for more coordinated in home care and support or residential aged care. Some service providers provide for day therapy services. At all times, older people are also able to access therapy and support services privately and when acute care is required, older people might access specialist geriatrics, rehabilitation and palliative care service through both the public and private hospital systems, although in some regions, these services might be limited.

Therefore, screening for frailty risk in general practice might allow the GP to identify earlier those aged 75 years and older who might benefit from a comprehensive assessment via the 75+ Health Assessment, following which a management plan including further investigation and referral to various services might occur in a proactive rather than a reactive approach. The relative ‘safety net’ provided by the MBS-funded items has important implications for how we approach the issue of accuracy within this study. The most important consideration for Australian GPs is likely to be avoiding false negatives, so as to avoid missing people who actually are frail. In contrast, the consequences of false positives are less significant given the options for subsequent follow-up. We are thus emphasising sensitivity over specificity in our study.

Aside from accuracy, feasibility and acceptability will also be critical factors in the selection of screening instruments. The feasibility and acceptability of frailty screening instruments within general practice has been significantly under-researched.16 Consequently, we have drawn on several feasibility studies addressing the introduction of non-frailty instruments in developing our approach,27 along with early results from focus groups on frailty conducted with Australian GPs. We will assess the feasibility and acceptability of the index tests from three perspectives: 1) feasibility of implementation within the context of a busy general practice environment; 2) acceptability to health service providers; 3) acceptability to consumers.

Within health research, passive case-finding (eg, using medical records) has been promoted as potentially advantageous over active case-finding due to lower cost and burden on study participants.28 It therefore could be viewed as a viable alternative to the active and rather intensive screening approach adopted in our study. However, passive case-finding is unviable within this context given that routinely collected medical records would be unlikely to capture the range of data required to detect frailty (with the possible exception of the construction of a frailty index) and are subject to high variability, a globally observed finding.28 These factors suggest an insufficiently reliable basis for its inclusion within our study.

In the absence of an Australian policy directive on frailty screening, screening will likely be directed to the most appropriate perceived candidates rather than to all persons of a given age. Preliminary findings from an aligned study of Australian GP perspectives on frailty and frailty screening29 indicate that in identifying potential candidates, it is probable that psychosocial factors may play a key role in GP considerations. For example, people who live alone, suffer depression or who have few social supports could potentially be at more risk from the impacts of frailty than those who have greater personal resources. The association of psychosocial factors with frailty is an emerging trend that has been reported within the research literature,30–35 although results to date have been mixed.36 Consequently, in order to better characterise those diagnosed as frail, we will also collect a range of psychosocial measures from our sample.

Objectives

Our study is designed to assess the (1) feasibility, (2) acceptability (to health service providers and consumers) and (3) diagnostic test accuracy of a number of frailty screening instruments within the context of Australian general practice. A fourth objective will be to explore the association of a range of psychosocial measures with frailty.

Methods and analysis

We will employ a prospective, cross-sectional and observational research design. We have reviewed our study design against the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy and Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) criteria. The study will be conducted between July 2017 and June 2018.

Setting

We will conduct the study within two general practice sites within South Australia, one metropolitan and one non-metropolitan. We will select practices based on purposive sampling.

Four practice nurses (registered nurses working in general practice)—two at each site—will be contracted to administer the index tests. Potential screeners will sign a consent form to enrol in the study. The screeners will attend training prior to commencement.

Participants

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

We will employ convenience sampling to recruit our sample. Patients will be eligible if they were aged 75+ years as at 30th June 2016 and booked to attend at the study sites for an upcoming appointment over a prespecified period during 2017.

Patients with dementia will be included as participants if written, informed consent is given by a responsible person who is available to attend with them at the study sessions. Inclusion will be discussed on a case-by-case basis with the patient's doctor. Doctors will cosign all consent forms involving patients with impaired ability to consent.

Exclusion criteria

We will exclude from the study those patients too ill to be assessed (ie, undergoing palliative care treatment or currently hospitalised), resident within residential care facilities or whose English is insufficient to fully participate.

Substudy 1: diagnostic test accuracy

Data collection

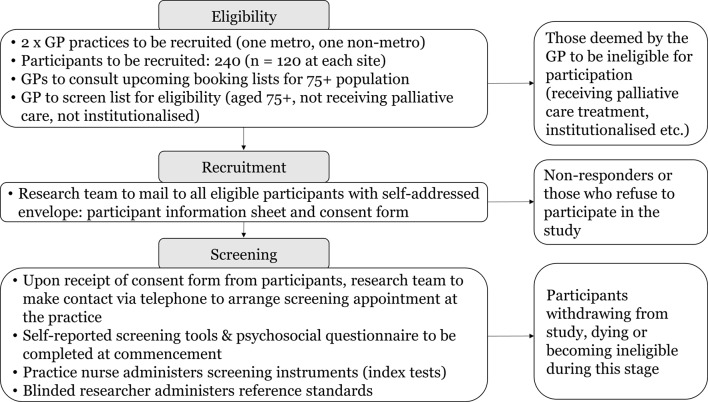

Figure 1 outlines the overall data collection process for the diagnostic test accuracy aspect of the study.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram (diagnostic test accuracy component). GP, general practitioner.

Recruitment

We will mail eligible participants an invitation letter, consent form and participant information sheet. We will ask potential participants to sign a consent form (or if unable to consent, a family member will be asked to sign on their behalf) to be returned to the research team via self-addressed envelope. Participants will be given the right to withdraw from participation should they wish to, as well as to opt out of completing individual instruments. We will collect demographic information (age, sex) from those electing not to participate in order to compare participants with non-participants.

On receipt of the consent form, we will telephone the participant to make an appointment to attend the screening session within 2 weeks to ensure information currency.

Recruitment will conclude on successful achievement of the required sample size (n=120 from each practice).

Screening session

On arrival, we will ask participants to complete a questionnaire including standard demographic information along with a select number of psychosocial instruments. They will then complete two self-reported index tests, returning each test as completed so that time to complete can be recorded. The practice nurse will then administer five administered index tests in random order. A blinded researcher (RA) will then administer the two reference standards. The total estimated duration of the appointment will be between 45 and 60 min.

Follow-Up

Where either of the reference standards indicates frailty, the participant will be offered a follow-up appointment with their GP. The research team will not collect data at this appointment.

Test methods

Index tests: overview

Following a literature review, we shortlisted 14 frailty screening instruments as candidates for inclusion as index tests through discussion with the clinician members of the research team. We considered validity (sensitivity at least 0.6), appropriateness to context (in English, transferable to Australia) time to implement (≤20 min) and delivery method (administered, ie, not solely records-based) in our deliberations. We ultimately selected the following instruments for inclusion: FRAIL Screening Instrument; Groningen Frailty Index; Program on Research for Integrating Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy (PRISMA-7); Edmonton Frail Scale; Gait Speed; Reported Edmonton Frail Scale and Kihon Checklist.

Index tests: administered by practice nurse

FRAIL Screening Instrument

The FRAIL Screening Instrument is a 5-item instrument addressing five aspects of frailty: fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness and loss of weight.37 Each component is allocated one point and all components are summed, resulting in a scale from 0 to 5. The original cut-points will be used in this study and were: frail (3–5), prefrail (1–2) and robust (0) health status.

Groningen Frailty Indicator

The Groningen Frailty Indicator is a multidomain frailty instrument found to be reliable and valid in a Dutch community-dwelling population.38 39 It has 15 items, resulting in a summed score from 0 to 15, with the frailty cut-point—also used in this study—set at 4 or more points.

PRISMA-7

The PRISMA-7 is a screening instrument validated in a community-dwelling population aged 75 years and older.40 It consists of a set of seven yes/no questions. Previous research indicates high sensitivity but limited specificity in identifying frailty.41 In the original formulation, also used in this study, three or more ‘yes’ responses indicated frailty.40

Edmonton Frail Scale

The Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS) is a measure developed and validated on a community-dwelling population aged 65+ years.42 Scored from 0 to 17, it measures frailty across ten domains including cognition, social support, medication use and functional performance. The original study does not provide a specification for frailty cut-point; this study will consequently follow previous studies in adopting a cut-point of 8 or more points to define frailty.43 44

Gait speed

Gait speed is a reliable and valid measure widely applied within the research literature.45 46 It has been found to have high sensitivity (but limited specificity) in identifying frailty.41 Following the recommendations of Castell et al and the wide application of this cut-off point in practice,46 we will apply a ≤0.8 m/s cut-off point for frailty in our study.

Index tests: self-reported

Reported Edmonton Frail Scale

The Reported Edmonton Frail Scale is a self-reported version of the Edmonton Frail Scale.44 The resultant scale ranges from 0 to 18 with the following cut-points defined: ‘not frail’ (0–5), ‘apparently vulnerable’ (6–7), ‘mild frailty’ (8–9), ‘moderate frailty’ (10–11) and ‘severe frailty’ (12–18). We will apply the original reported cut-point of 8 or more in our study.

The Kihon Checklist

The Kihon Checklist is reported to be a reliable self-reported instrument for predicting frailty in older adults.47 It consists of 25 yes/no questions covering a range of domains. We will replicate the frailty cut-point reported in Sewo Sampaio et al 48 of a total of seven or more ‘yes’ questions.

Reference standards

We consulted prior research for potential reference standards, identifying three commonly used candidates25 41: CGA, the Frailty Phenotype (based on the Cardiovascular Health Study definition7) and Frailty Index (based on the Canadian Study of Health and Aging49).

The CGA, an interdisciplinary diagnostic procedure aiming to identify a range of issues in older people, is commonly thought to be the gold standard for frailty identification.25 However, its time-consuming and resource intensive nature,41 50 makes it beyond the scope of implementation as a reference standard within our study.

The alternatives—the Frailty Phenotype and Frailty Index—have admittedly been labelled as ‘different instruments for different purposes’,51 due largely to the inclusion of disability items in the Frailty Index versus the Phenotype. Our inclusion of both as reference standards might therefore be seen as controversial, if not for the fact that the version of the Frailty Index we will apply in this study explicitly excludes disability items.

The remaining differences between the two standards mainly relate to the feasibility of applying them within general practice, a factor that does not apply here given their use as reference standards rather than index tests. Additionally, the risk of differential verification bias, present when not all test subjects undertake both reference standards,52 is not expected to impact our study as all participants will undertake both reference standards equally. Results for both standards will be presented, along with a detailed analysis of cases varying between the two.

We contend that our decision to include both reference standards offers a significant contribution to the frailty evidence base, given we are operating with an absence of consensus about which reference standard is superior. Including both reference standards will ensure our research remains relevant into the future, regardless of subsequent changes in expert opinion. Given we are still at an early stage of our understanding about frailty screening within Australia, we maintain that in this instance, more information will ultimately prove better than less.

Frailty Phenotype

The Frailty Phenotype has received broad acceptance worldwide,46 having been externally validated within several large epidemiological studies.41 53 Recognised drawbacks include its lack of cognitive and psychosocial domains,33 however, it has predicted significant negative health-related outcomes across numerous studies to date.33 54

This study will implement original formulation by Fried et al, as shown below [7:M156].

Shrinking (unintentional weight loss of ≥10 pounds in the prior year or, at follow-up, of ≥5% of body weight in the prior year by direct measurement of weight), as assessed by the question: "n the last year, have you lost more than 10 pounds unintentionally (ie, not due to dieting or exercise)?”

Weakness: we will measure grip strength with a hand-held Jamar dynamometer, assessing maximal grip strength (kg) in the dominant hand (average of three measures). Fried's cut-points are shown in table 1 and will be used in this study.

- Poor endurance and energy: indicated by self-reported exhaustion based on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale.55 The frailty criterion is satisfied if the participant response is ‘a moderate amount’ or ‘most of the time’ in answer to the following:

- (a) "I felt that everything I did was an effort."

- (b) "I could not get going."

Slowness: measured by gait speed (time taken to walk 15 feet). We will employ the cutoffs reported in Fried et al: ≥7 s (men of height ≤173 cm and women ≤159 cm), and ≥6 s (men of height >173 cm and women >159 cm).

Low physical activity level: measured by the short-form Minnesota Leisure Time Activity questionnaire.56 The questionnaire is used to derive a weighted score of kilocalories expended/week, with the following cut-points: men <383 and women <270 kcals/week.

Table 1.

Fried cut-off criteria for frailty (grip strength)

| Men | Women | ||

| BMI | Cut-off (kg) | BMI | Cut-off (kg) |

| ≤24 | ≤29 | ≤23 | ≤17 |

| 24.1–26 | ≤30 | 23.1–26 | ≤17.3 |

| 26.1–28 | ≤30 | 26.1–29 | ≤18 |

| >28 | ≤32 | >29 | ≤21 |

BMI; body mass index.

The frailty cut-points specified in the original model and used within this study were that three or more components meeting the criteria indicate frailty.

Adelaide Frailty Index

The second reference standard is the Adelaide Frailty Index (AFI), a 42-item variant of a standard frailty index based on the methodology reported by Searle et al.57 It was developed by Mark Thompson as part of ongoing work within the regional geriatric health service (Thompson et al, unpublished).58 The frailty cut-point for the AFI, also applied within this study, is a score of 9 or more (ie, 21% or more).

The AFI includes elements drawn from the following frailty risk factors: shrinking, exhaustion, low energy expenditure, slowness, weakness, cognitive impairment, falls and balance, urinary incontinence, polypharmacy, oral health, pain, mental health and chronic conditions. Several questions within the AFI were derived from validated screening instruments in common use within those domains. The AFI intentionally excludes disability items, in recognition of the distinction between disability and frailty.59

Psychosocial instruments

In recognition of the complex relationship between psychosocial factors and frailty, we will administer five psychosocial instruments within the self-complete questionnaire. Depression is associated with frailty among older people34 and is measured here via the commonly used Geriatric Depression Scale-15.60 Social isolation will be measured by an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale-6, which has been widely used worldwide to measure isolation among older people.61 62 A measure relating to sense of perceived control, as originally conceptualised and validated by Lachman and Weaver,63 has previously been demonstrated to play a mediating role with respect to frailty35 and will be included within the set. Likewise, negative self-perceptions of ageing have been found to have a modifying effect on frailty64 and will be included in the form of the Brief Ageing Perceptions Questionnaire.65 Lastly, a specific measure of older people's quality of life will be measured using the ICEpop CAPability measure for Older people (ICECAP-O).66

Other measures

In addition to the index tests collected at the screening appointment, the practice nurse will also collect the Nottingham Extended ADL scale (NEADL).67 The NEADL is a valid and reliable measure of functioning that has been widely applied among older populations.68

Data management

We will collect data manually, verifying it where required against clinical records. We will identify participants by a unique identifier, with linkage keys to be stored separately from the data. Data will be entered into an SPSS database. We will subject 5% of the records to a random audit by a second researcher to test data quality. We will store all deidentified study data on a password-protected drive.

Statistical methods

Sample size

We derived a sample size estimate using a methodology reported by Buderer incorporating consideration of disease prevalence.69 This calculation was complicated by the absence of a reliable Australian frailty prevalence rate, so we drew on a number of community-based studies to derive a prevalence estimate. Two Australian studies suggested frailty prevalence rates of 25% for the 75+ and 17.5% for the 70+ (Thompson et al, unpublished data and Widagdo et al 18), and a Spanish study reported a 19% prevalence among the 75+.46 Ultimately, we selected a 20% prevalence rate as a conservative choice, applying this figure within Buderer's formula along with sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 60%. The clinically acceptable width of the 95% CIs for sensitivity and specificity was set to be no larger than 10, giving a minimum estimated sample size of 173 persons. We will aim to recruit at least 240 participants. This allows for a buffer of 25% above the minimum sample to address attrition in the short period between consent and attendance at the screening appointment while also allowing for the possibility of a lower than estimated prevalence of frailty in the population.

Analysis

We will examine the distribution of quantitative variables visually and by using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality.70 Categorical variables will be described as frequencies. Quantitative variables will be displayed as mean±SD, where normally distributed or as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles were asymmetrically distributed. Where the results for an index test or reference standard are indeterminate or incomplete, results for that participant will be excluded. No imputation will be performed for missing data.

Our accuracy analysis will compare the results of each index test against each reference standard. We will construct variables reflecting each frailty instrument and define the presence of frailty according to the specified cut-points. We will create standard 2×2 tables for each index test against each reference standard, and calculate sensitivity and specificity with their corresponding 95% CIs, along with positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios. We will determine the extent of agreement between the index tests and reference standards by calculating Cohen's kappa.

To analyse the relationship between the psychosocial variables and frailty, we will define the presence of frailty as a binary variable (frail/not frail) according to the Fried criteria as measured in the Frailty Phenotype. We will use binomial (binary) logistic regression to analyse the association strength (OR) for the frail state with the psychosocial variables using the non-frail state as the comparison category. We will consider a p value of <0.05 to be statistically significant. The data will be analysed using the latest available version of the SPSS statistical software (version 24.0 SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

To test inter-rater reliability, 8 subjects tested by each screener (32 in all) will be asked to repeat the index test session including self-reported tests with a second blinded screener within 48 hours after the initial rating. Given the binary nature of the outcome (ie, frail/not frail) and multiple raters, the kappa coefficient will be used to ascertain agreement, with the minimum acceptable value set to 0.6. We will ask every third participant participating at each research site in the main study to participate in the inter-rater reliability component, proceeding until such time as the site and screener quota is reached.

Substudy 2: feasibility and acceptability

We will apply a convergent parallel mixed methods approach to the analysis of feasibility and acceptability. We define mixed methods research, following Johnson et al, as a type of research combining ‘elements of qualitative and quantitative research approaches … for the broad purposes of breadth and depth of understanding and corroboration’ (Johnson et al, p. 123).71 Mixed methods have increasingly been applied within the health sciences in recent years, where a more complete understanding of an issue is allowed than by a quantitative or qualitative approach alone.72

Data collection and management

Feasibility

We will measure the feasibility of the index tests by collecting the following information about each test:

Noted by research team prior to data collection

Education or training required to administer each test

Special equipment/devices required

Physical space required

Collected by practice nurse during session

Time to administer each instrument

Instrument completion by respondents (include any reasons for non-completion)

Acceptability to health service providers

We will ask the screeners to complete a standardised form to capture initial impressions of the instruments during the data collection period. We will also request that screeners participate in an interview conducted within a week after data collection has concluded to gather their overall impressions of the instruments. We will rate each instrument against a 1–10 Likert scale measuring ease of implementation as well as including a number of open-ended questions. We will ask screeners to rank the instruments in order of preference.

Acceptability to consumers

We will pilot an acceptability questionnaire with 26 participants during data collection (13 to be recruited from each research site, respectively). This figure represents just over a 10% sample of participants, as well as exceeding the n=25 threshold recommended by Herzog in her discussion of appropriate sample sizes for aims related to instrumentation.73 We will ask every second participant participating at each research site in the main study to participate in the acceptability component. Sampling will proceed until the site quota is reached.

After applying each index test the screener will ask participants their impressions of the instrument and record the response. We will also ask participants to complete a 1–10 Likert-scale questionnaire measuring perceived ease in completing each instrument. In addition, screeners will collect refusal rates from all respondents, including reason for refusal.

Data management

Separate variables will be developed in SPSS to represent each numerical data measure. We will record and transcribe the screener interviews, uploading the transcripts to the NVivo software package. We will also store and analyse comments reflecting impressions of the instruments within NVivo. Otherwise, we will follow similar data security and deidentification procedures as specified under Diagnostic Accuracy.

Data analysis

Feasibility

We will use descriptive statistics and tables to describe the results of the feasibility analysis, structuring these according to themes drawn out in our early focus groups.

Acceptability to health service providers

Two researchers will employ a thematic analysis approach to code the data contained within the screener transcripts. We will use these codes to develop acceptability categories and themes. Codes and themes will be reviewed with a third researcher experienced in qualitative methodology to promote rigour.

We will create joint displays (ie, side-by-side comparison tables) of ranking results for the screening instruments and qualitative comments about screener impressions of the instruments to facilitate data integration.

Acceptability to consumers

We will present consumer ratings for each instrument (Likert scale) as frequency tables, along with reporting the mean, range and proportion in each group. We will use a joint display to add indicative qualitative comments about these results, aiming to represent the range of opinion for each instrument. Against each instrument, we will also present summary descriptive data based on the whole sample describing refusal rates and reason for refusal.

Interpretation

We will structure our discussion of the results by each dimension of feasibility/acceptability, noting the extent of convergence between the qualitative and quantitative data sources where appropriate. Where divergence occurs, we will discuss potential causes and implications.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics and informed consent

The study has been approved by the Torrens University Higher Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants and screeners prior to participation. Where informed consent cannot be obtained due to cognitive impairment, consent will be sought from an attendant person responsible for the participant and cosigned by the GP.

Participant safety

At each site the health service provider will do a brief safety analysis prior to commencement to ensure it is safe to proceed. We will offer participants the right to refuse participation in physical tests they deem unsafe. Where participants are unable to complete their appointment due to fatigue, we will offer them the option to attend a separate session within the following 48 hours in order to complete data collection.

Dissemination

We will publish our findings within peer-reviewed journals and present at relevant conferences within the field. Separate publications will address findings for the diagnostic test accuracy and psychosocial research objectives. At no time will participants be identifiable within the research dissemination process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mark Thompson, Occupational Therapist, of the Centre of Research Excellence Frailty Transdisciplinary Research to Achieve Healthy Ageing for allowing the use of the Adelaide Frailty Index. MA also acknowledges fellowship support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

Contributors: The research question, concept and design were formulated by RA, JB, RV, SY, TS, JK, MC, MA and AK. Preparation of the manuscript was completed by RA. RA, JB, RV, TS, SY, JK, MC, MA and AK reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia via funding provided for the Centre of Research Excellence in Frailty and Healthy Ageing, grant number GNT 1102208. We would also like to acknowledge Resthaven for funding support related to general practitioner engagement.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. ONU. World population, Ageing. 2015;164. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016;45:1–8. 10.1093/ageing/afw039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, et al. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:104–14. 10.1016/j.arr.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, et al. The predictive validity of the Tilburg Frailty Indicator: disability, health care utilization, and quality of life in a population at risk. Gerontologist 2012;52:619–31. 10.1093/geront/gnr135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coelho T, Paúl C, Gobbens RJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of short-term adverse outcomes. PeerJ 2015;3:e1121 10.7717/peerj.1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kojima G, Iliffe S, Jivraj S, et al. Association between frailty and quality of life among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:716–21. 10.1136/jech-2015-206717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M157. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vermeulen J, Neyens JC, van Rossum E, et al. Predicting ADL disability in community-dwelling elderly people using physical frailty indicators: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2011;11:33 10.1186/1471-2318-11-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Widagdo IS, Pratt N, Russell M, et al. Predictive performance of four frailty measures in an older Australian population. Age Ageing 2015;44:967–72. 10.1093/ageing/afv144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kojima G. Frailty as a predictor of Future Falls among Community-Dwelling older people: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:1027–33. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson TN, Wallace JI, Wu DS, et al. Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:37–42. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chainani V, Shaharyar S, Dave K, et al. Objective measures of the frailty syndrome (hand grip strength and gait speed) and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2016;215:487–93. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, et al. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1487–92. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3222.0 Population projections 2012 (Base) to 2101. 2013.

- 15. Drubbel I, Numans ME, Kranenburg G, et al. Screening for frailty in primary care: a systematic review of the psychometric properties of the frailty index in community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:27 10.1186/1471-2318-14-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lacas A, Rockwood K. Frailty in primary care: a review of its conceptualization and implications for practice. BMC Med 2012;10:4 10.1186/1741-7015-10-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Franchini M, Pieroni S, Fortunato L, et al. Integrated information for integrated care in the general practice setting in Italy: using social network analysis to go beyond the diagnosis of frailty in the elderly. Clin Transl Med 2016;5:24 10.1186/s40169-016-0105-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Widagdo I, Pratt N, Russell M, et al. How common is frailty in older Australians? Australas J Ageing 2015;34:247–51. 10.1111/ajag.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cesari M, Vellas B. Response to the letter to the editor: 'What is missing in the validation of frailty instruments?'. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:143–4. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xue Q-L, Varadhan R, Morley JE, et al. What is missing in the validation of Frailty Instruments?.‘Frailty Consensus: A Call to Action’. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:392–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Turner G, Clegg A. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing 2014;43:744–7. 10.1093/ageing/afu138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women's health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:262–6. 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The Orlando Frailty Conference Group. Raising awareness on the urgent need to implement frailty into clinical practice. J Frailty Aging 2013;2:121–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pialoux T, Goyard J, Lesourd B. Screening tools for frailty in primary health care: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012;12:189–97. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamirudin AH, Ghosh A, Charlton K, et al. Trends in uptake of the 75+ health assessment in Australia: a decade of evaluation. Aust J Prim Health 2015;21:423–8. 10.1071/PY14074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elley CR, Dawes D, Dawes M, et al. Screening for lifestyle and mental health risk factors in the waiting room: feasibility study of the Case-finding Health Assessment Tool. Can Fam Physician 2014;60:e527–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Rocca WA, et al. Passive case-finding for alzheimer's disease and dementia in two U.S. communities. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:53–60. 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Archibald MM, Ambagtsheer R, Beilby J, et al. Perspectives of Frailty and Frailty Screening: protocol for a collaborative knowledge translation approach and qualitative study of Stakeholder Understandings and Experiences. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:87 10.1186/s12877-017-0483-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andrew MK, Fisk JD, Rockwood K. Psychological well-being in relation to frailty: a frailty identity crisis? Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1347–53. 10.1017/S1041610212000269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sánchez-García S, Sánchez-Arenas R, García-Peña C, et al. Frailty among community-dwelling elderly Mexican people: prevalence and association with sociodemographic characteristics, health state and the use of health services. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014;14:395–402. 10.1111/ggi.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dent E, Hoogendijk EO. Psychosocial factors modify the association of frailty with adverse outcomes: a prospective study of hospitalised older people. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:108 10.1186/1471-2318-14-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin FC, Brighton P. Frailty: different tools for different purposes? Age Ageing 2008;37:129–31. 10.1093/ageing/afn011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buigues C, Padilla-Sánchez C, Garrido JF, et al. The relationship between depression and frailty syndrome: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:762–72. 10.1080/13607863.2014.967174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mooney CJ, Elliot AJ, Douthit KZ, et al. Perceived control mediates effects of socioeconomic status and chronic stress on Physical Frailty: findings from the Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2016:1–10. 10.1093/geronb/gbw096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mulasso A, Roppolo M, Giannotta F, et al. Associations of frailty and psychosocial factors with autonomy in daily activities : a cross-sectional study in italian community-dwelling older adults. 2016:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:601–8. 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bielderman A, van der Schans CP, van Lieshout MR, et al. Multidimensional structure of the Groningen Frailty Indicator in community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:86 10.1186/1471-2318-13-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S, et al. Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:M962–5. 10.1093/gerona/59.9.M962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Raîche M, Hébert R, Dubois MF. PRISMA-7: a case-finding tool to identify older adults with moderate to severe disabilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2008;47:9–18. 10.1016/j.archger.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clegg A, Rogers L, Young J. Diagnostic test accuracy of simple instruments for identifying frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2015;44:148–52. 10.1093/ageing/afu157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, et al. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing 2006;35:526–9. 10.1093/ageing/afl041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, et al. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1537–51. 10.1111/jgs.12420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, et al. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing 2009;28:182–8. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fritz S, Lusardi M. Walking speed: the sixth vital sign. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2009;32:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Castell MV, Sánchez M, Julián R, et al. Frailty prevalence and slow walking speed in persons age 65 and older: implications for primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:86 10.1186/1471-2296-14-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sewo Sampaio PY, Sampaio RA, Yamada M, et al. Systematic review of the Kihon Checklist: is it a reliable assessment of frailty? Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016;16:893–902. 10.1111/ggi.12833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sewo Sampaio PY, Sampaio RAC, Yamada M, et al. Comparison of frailty between users and nonusers of a day care center using the Kihon Checklist in Brazil. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics 2014;5:82–5. 10.1016/j.jcgg.2014.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489–95. 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, et al. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e437-44 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cesari M, Gambassi G, van Kan GA, et al. The frailty phenotype and the frailty index: different instruments for different purposes. Age Ageing 2014;43:10–12. 10.1093/ageing/aft160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. de Groot JA, Dendukuri N, Janssen KJ, et al. Adjusting for differential-verification bias in diagnostic-accuracy studies: a Bayesian approach. Epidemiology 2011;22:234–41. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318207fc5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Theou O, Cann L, Blodgett J, et al. Modifications to the frailty phenotype criteria: systematic review of the current literature and investigation of 262 frailty phenotypes in the survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Ageing Res Rev 2015;21:78–94. 10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cesari M, Demougeot L, Boccalon H, et al. A self-reported screening tool for detecting community-dwelling older persons with frailty syndrome in the absence of mobility disability: the FiND questionnaire. PLoS One 2014;9:1–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B, et al. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 1978;31:741–55. 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, et al. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008;8:24 10.1186/1471-2318-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thompson MQ, Yu S, Theou O, et al. Adelaide Frailty Index. 2016.

- 59. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:255–63. 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sheikh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 1986;5:165–73. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006;46:503–13. 10.1093/geront/46.4.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen S, Honda T, Chen T, et al. Screening for frailty phenotype with objectively-measured physical activity in a west Japanese suburban community: evidence from the Sasaguri Genkimon Study. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:36 10.1186/s12877-015-0037-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:763–73. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Robertson DA, Kenny RA. Negative perceptions of aging modify the association between frailty and cognitive function in older adults. Pers Individ Dif 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sexton E, King-Kallimanis BL, Morgan K, et al. Development of the brief ageing perceptions questionnaire (B-APQ): a confirmatory factor analysis approach to item reduction. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:44 10.1186/1471-2318-14-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Grewal I, Lewis J, Flynn T, et al. Developing attributes for a generic quality of life measure for older people: preferences or capabilities? Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1891–901. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nouri FM, Lincoln NB. An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 1987;1:301–5. 10.1177/026921558700100409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yohannes AM, Roomi J, Waters K, et al. A comparison of the Barthel index and Nottingham extended activities of daily living scale in the assessment of disability in chronic airflow limitation in old age. Age Ageing 1998;27:369–74. 10.1093/ageing/27.3.369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Buderer NM. Statistical methodology: I. incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:895–900. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2012;10:486–9. 10.5812/ijem.3505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of Mixed methods Research. J Mix Methods Res 2007;1:112–33. 10.1177/1558689806298224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in Health Science Mixed methods Research through Joint displays. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:554–61. 10.1370/afm.1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health 2008;31:180–91. 10.1002/nur.20247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.