Abstract

Objectives

Hypernatraemia is one of the major electrolyte disorders associated with mortality among critically ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs). It is unclear whether this applies to patients with cerebrovascular diseases in whom high sodium concentrations may be allowed in order to prevent cerebral oedema. This study aimed to examine the association between ICU-acquired hypernatraemia and the prognosis of patients with cerebrovascular diseases.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The incidence of ICU-acquired hypernatraemia was assessed retrospectively in a single tertiary care facility in Japan.

Participants

Adult patients (≥18 years old) whose length of stay in ICU was >2 days and those whose serum sodium concentrations were 130–149 mEq/L on admission to ICU were included.

Outcome measures

28-day in-hospital mortality risk was assessed by Cox regression analysis. Hypernatraemia was defined as serum sodium concentration ≥150 mEq/L. Using multivariate analysis, we examined whether ICU-acquired hypernatraemia and the main symptom present at ICU admission were associated with time to death among ICU patients. We also evaluated how the maximum and minimum sodium concentrations during ICU stay were associated with mortality, using restricted cubic splines.

Results

Of 1756 patients, 121 developed ICU-acquired hypernatraemia. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed an association between ICU-acquired hypernatraemia and 28-day mortality (adjusted HR, 3.07 (95% CI 2.12 to 4.44)). The interaction between ICU-acquired hypernatraemia and cerebrovascular disease was significantly associated with 28-day mortality (HR, 3.03 (95% CI 1.29 to 7.15)). The restricted cubic splines analysis of maximum serum sodium concentration in ICU patients determined a threshold maximum of 147 mEq/L. There was no significant association between minimum sodium concentration and mortality.

Conclusions

ICU-acquired hypernatraemia was associated with an increased mortality rate among critically ill patients with cerebrovascular diseases; the threshold maximum serum sodium concentration associated with mortality was 147 mEq/L.

Keywords: cerebrovascular disease, epidemiology, hypernatraemia, intensive care unit, restricted cubic spline

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We determined that intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired hypernatraemia is associated with mortality interactively with other symptoms in critically ill patients, especially in those with cerebrovascular diseases.

We determined the optimal serum sodium concentration range for ICU-admitted patients with cerebrovascular diseases by investigating the association between mortality and the maximum and minimum serum sodium concentration during the ICU stay.

The data collected for the study were specific to the time when the patients were admitted to ICU; hence, we were not able to determine whether patients developed hypernatraemia after being discharged from ICU.

Introduction

Hypernatraemia is a common electrolyte disturbance occurring in patients who admitted to medical, surgical and neurological intensive care units (ICUs). Previous studies showed that ICU-acquired hypernatraemia (IAH) is an independent predictor of increased mortality.1–5 Hypernatraemia has been shown to be a risk factor for mortality in patients admitted to ICU for sepsis6 and in patients admitted to neurological ICU.7–10 On the other hand, hypernatraemia on admission was not associated with mortality among patients with respiratory failure.11 Thus, whether the effect of hypernatraemia on mortality is augmented by the coexisting clinical condition at the time of ICU admission remains unclear.

Hypernatraemia is common among the patients with neurological symptoms; it is also a risk factor for mortality. Critically ill patients with neurological diseases are susceptible to developing hypernatraemia for a variety of reasons, including an impaired thirst mechanisms and physical disability hindering voluntary drinking. Insensible loss of water may increase in patients with fever due to infectious or non-infectious causes. Moreover, hypernatraemia may be induced by the therapeutic use of osmotic diuretics or hypertonic saline to lower intracranial pressure (ICP)12; a study showed that a reduction in ICP was correlated with a rise in the serum sodium concentration.13 Thus, in patients with cerebrovascular disease (CVD), the ideal serum sodium concentration is difficult to determine. Hypernatraemia may be beneficial in controlling ICP, but it may be associated with increased morbidity and mortality among critically ill patients, including those with neurological conditions.

Few studies have targeted patients with cerebral infarction or spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage, and most of the prior studies were conducted among patients who admitted to neurological ICU.8–10 Prior studies concluded that the peak serum sodium concentration was a strong predictor for mortality. However, the cut-off point varied between studies, and these studies included patients with cerebral infarction and spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage and those with traumatic brain injury and other neurological diseases.

The objective of this study was to investigate whether IAH was associated with mortality interactively with other symptoms, especially CVDs. We also investigated the optimal serum sodium concentration range for patients admitted to ICU. The findings of this study may have implications for the choice of therapeutic and maintenance fluids administered to critically ill patients with neurological conditions.

Subjects and methods

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted among patients admitted to ICU in Toyohashi Municipal Hospital from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2015. Toyohashi Municipal Hospital is a tertiary referral hospital. The ICU manages both medical and surgical patients and is staffed by non-intensivists. The timing of and interval between laboratory examinations are determined by each doctor. Blood samples of planned laboratory examination are drawn between 05:00 and 06:00 under starved conditions. Some ICU beds are also used as recovery beds for patients admitted from emergency department; such patients are usually discharged from ICU within 2 days.

Using the data from these patients, we first examined whether IAH was associated with mortality using survival analysis. Second, we added a subgroup analysis of the main symptom on admission. Third, we examined the association between mortality and the maximum and minimum sodium concentrations during ICU stay to find the optimal cut-off value among patients with CVD. The outcome of interest was 28-day in-hospital mortality.

Study population and definitions

Adult patients (≥18 years old) whose length of stay in ICU was >2 days and those whose serum sodium concentrations were 130–149 mEq/L on admission to ICU were included. We excluded patients whose initial serum sodium concentration results were missing and brain-dead patients admitted to the ICU for planned organ donation.

If a patient was admitted to the ICU more than once during one hospital admission, data were obtained from the first ICU admission that was longer than 2 days in duration or from the admission during which the patient developed IAH. Patients who developed hypernatraemia outside of the ICU were not classified as cases of IAH.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Toyohashi Municipal Hospital (No. 248), and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Hypernatraemia was defined as a serum sodium concentration ≥150 mEq/L. IAH was defined as hypernatraemia occurring ≥12 hours after ICU admission in patients with a normal serum sodium concentration at ICU admission. Patients who developed hypernatraemia within the first 12 hours of ICU admission were excluded.

Data collection

The following data were recorded: age, sex, vital signs, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) score14 on admission to ICU; main symptoms at ICU admission; biochemical variables; and ICU exposures, such as mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy. The main symptom at ICU admission was classified into the following categories: sepsis, respiratory failure, neurological symptom, acute kidney injury (AKI) and other medical conditions. Sepsis was defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, as represented by an increase in the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score (≥2 points).15 Respiratory failure was defined as P/F ratio <200 or the need for mechanical ventilation due to respiratory insufficiency. The neurological category included CVD, traumatic head injury, refractory status epilepticus, encephalopathy and meningoencephalitis without sepsis. It was divided into two groups: CVD (including ischaemic cerebral infarction and spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage) and other neurological diseases. AKI was defined in accordance with the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome guidelines,16 as follows:

an increase in serum creatinine level of ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 mmol/L) within 48 hours or

an increase in serum creatinine level to ≥1.5 times above its baseline value, known or presumed to have occurred within the preceding 7 days or

a urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours.

Among patients with CVD, we also reviewed the modified Rankin Scale score on admission and the type of CVD (ischaemic cerebral infarction, spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage). The modified Rankin Scale is a validated measurement of the overall handicap scale for patients who have suffered a stroke.17 18 The scale was assessed by trained neurologists on admission. A score of ≤3 indicates favourable neurological function.19

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics were compared between IAH and non-IAH patients using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. Continuous variables are expressed as the median (IQR) and categorical variables are expressed as number and proportion, as appropriate. Cumulative probabilities of mortality were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. To identify predictors of 28-day in-hospital mortality, the log-rank test and univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were employed. Survival time was calculated as the time from ICU admission to death (either in ICU or in hospital). Data for patients with a hospital stay longer than 28 days were censored at 28 days. IAH was included in the regression model as a time-dependent prognostic factor.

The multivariate analysis was adjusted for age, sex, APACHE-II score, AKI, sepsis, emergency surgery prior to the ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and initiation of renal replacement therapy. The proportional hazards assumption for covariates was tested using scaled Schoenfeld residuals.

We also performed a subgroup analysis of the main symptoms on ICU admission, as defined above. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to examine whether IAH, the symptoms and the interaction between IAH and symptoms were associated with mortality among ICU patients, adjusted for age, sex, APACHE-II score, use of mechanical ventilation and initiation of renal replacement therapy. When we considered the interaction, we centred each variables by subtracting the mean value from each variables to reduce the multicollinearity, and we calculated the interaction terms.

To assess the association between the maximum and minimum sodium concentrations and mortality, we performed a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis and restricted cubic splines (RCSs).20 The multivariate logistic regression analysis was adjusted for age, sex, APACHE-II score, GCS, length of ICU stay, types of CVD and favourable neurological condition (defined as modified Rankin Scale score ≤3) on ICU admission. In the RCS, the non-linear association between predictor and outcome was expressed as a spline curve combined cubic polynomials and linear terms. In this study, we set three knots to analyse the associations between predictor and outcome, placed on the 10 th, 50 th and 90 th percentile of the predictor value range.

Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software, V.14.1 (STATA; http://www.stata.com).

Results

Study participants

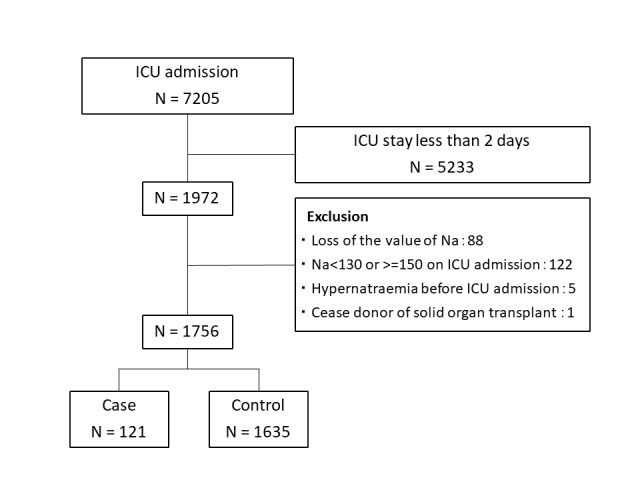

During the study period, 7205 patients were admitted to the ICU. The following exclusions were made: 5233 patients were discharged from the ICU within 2 days of admission, 122 patients had a serum sodium concentration outside the normal range on ICU admission, 88 patients had missing data, 5 patients developed hypernatraemia before ICU admission and 1 patient was a deceased organ transplant donor. The final cohort comprised 1756 patients who were normonatraemic on admission to the ICU. Figure 1 shows the selection of the study participants and IAH cases. There were 121 cases of IAH, with a median serum sodium concentration of 152 mEq/L (IQR: 150–153 mEq/L). The median serum sodium concentration of those who did not develop IAH was 142 mEq/L (IQR: 138–144 mEq/L). The median duration of IAH was 4 (3–8) days in total and 3 (2–8) days for patients with CVD.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients admitted during the study period. ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 1 compares the baseline demographic data, medical exposures in ICU and outcomes between patients who developed hypernatraemia and those who did not. The incidence of IAH was 6.9% (121 ⁄1756). In terms of main symptom category, 11.6% (45/388) of patients with sepsis, 10.0% (46/461) of patients with respiratory failure, 9.5% (33/346) of patients with CVD and 11.2% (45/403) of patients with AKI developed IAH. Among IAH cases, sepsis and neurological diseases were common reasons for ICU admission. A significantly higher proportion of patients with IAH required mechanical ventilation. ICU and in-hospital mortality were higher and the length of ICU stay was longer among IAH cases.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, exposures in ICU and outcomes

| Category | Variables | IAH cases (n=121) | Non-IAH cases (n=1635) | p Value |

| Characteristics | Age (years) | 71 (61–78) | 69 (58–79) | 0.38 |

| Male | 85 (70.3) | 1016 (62.1) | 0.075 | |

| APACHE-II score | 19 (13–24) | 12 (8–18) | <0.001* | |

| Main symptom at ICU admission | Sepsis | 45 (37.2) | 343 (21.0) | <0.001* |

| Respiratory failure | 46 (38.0) | 415 (25.4) | 0.002* | |

| Neurological | 45 (37.2) | 501 (30.6) | 0.13 | |

| CVD | 33 (27.3) | 313 (19.1) | 0.030* | |

| Non-CVD | 12 (9.9) | 188 (11.5) | 0.60 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 45 (37.2) | 358 (21.9) | <0.001* | |

| Other medical conditions | 7 (5.8) | 307 (18.8) | <0.001* | |

| Interventions | Surgery prior to ICU admission | 0.23 | ||

| Elective surgery | 4 (3.3) | 102 (6.2) | ||

| Emergency surgery | 26 (21.5) | 278 (17.0) | ||

| Renal replacement therapy | 11 (9.1) | 128 (7.8) | 0.62 | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 86 (71.1) | 606 (37.1) | <0.001* | |

| Outcomes | Length of ICU admission (days) | 9 (5,15) | 4 (3,6) | <0.001* |

| All-cause hospital mortality | 56 (46.3) | 193 (11.9) | <0.001* | |

| All-cause 28-day mortality | 42 (35.0) | 145 (8.9) | <0.001* |

Continuous data are presented as the median (IQR). Categorical data are presented as n (%).

*p<0.05.

APACHE, Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; IAH, ICU-acquired hypernatraemia; ICU, intensive care unit.

Outcomes of patients with IAH

The cumulative probabilities of mortality using the Kaplan-Meier method are shown in online supplementary file 1. Patients with IAH had a poorer prognosis. A univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed that IAH was associated with 28-day mortality (adjusted HR, 3.23 (95% CI 2.22 to 4.71)).

bmjopen-2017-016248supp001.jpg (167.8KB, jpg)

Interaction between IAH and clinical symptoms

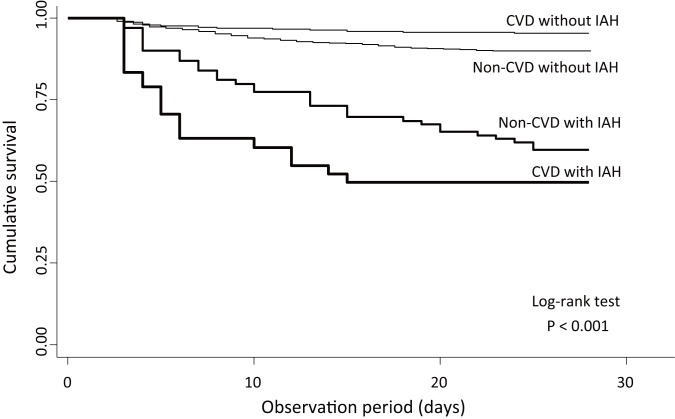

We examined the association between 28-day mortality and the interaction between IAH and the clinical symptoms, as shown in table 2. IAH was associated with 28-day mortality in all categories. There was significant association among patients with neurological symptoms, particularly patients with CVD. Among patients with neurological symptoms, the adjusted HRs of IAH, symptom and the interaction term were 2.52 (1.59–3.97), 0.94 (0.62–1.42) and 2.31 (1.09–4.90), respectively. In patients with CVD, the adjusted HRs of IAH, symptom and the interaction terms were 2.64 (1.72–4.04), 0.72 (0.42–1.25) and 3.03 (1.29–7.15), respectively. Figure 2 shows the association between mortality and the interaction between IAH and CVD.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of the interaction between IAH and clinical symptoms

| Symptom | Variable | HR† | 95% CI | p Value |

| Sepsis | IAH | 3.64 | 2.50 to 5.29 | <0.001* |

| Sepsis | 1.30 | 0.94 to 1.81 | 0.112 | |

| Interaction | 0.52 | 0.25 to 1.07 | 0.076 | |

| Neurological | IAH | 3.27 | 2.25 to 4.76 | <0.001* |

| Neurological | 0.99 | 0.67 to 1.46 | 0.95 | |

| Interaction | 2.31 | 1.09 to 4.90 | 0.029* | |

| CVD | IAH | 3.30 | 2.26 to 4.82 | <0.001* |

| CVD | 0.78 | 0.47 to 1.30 | 0.34 | |

| Interaction | 3.03 | 1.29 to 7.15 | 0.011* | |

| Respiratory | IAH | 3.69 | 2.49 to 5.47 | <0.001* |

| Respiratory failure | 1.38 | 0.96 to 1.98 | 0.079 | |

| Interaction | 0.73 | 0.37 to 1.48 | 0.39 | |

| AKI | IAH | 3.64 | 2.51 to 5.30 | <0.001* |

| AKI | 1.01 | 0.71 to 1.42 | 0.97 | |

| Interaction | 0.56 | 0.27 to 1.17 | 0.12 |

*p<0.05.

Adjusted for age, gender, APACHE-II score, renal replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation.

AKI, acute kidney injury; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; IAH, intensive care unit-acquired hypernatraemia.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the interaction between intensive care unit-acquired hypernatraemia and cerebrovascular diseases. CVD, cerebrovascular disease; IAH, intensive care unit-acquired hypernatraemia.

Maximum and minimum serum sodium concentrations and mortality

The clinical characteristics of patients with CVD are shown in table 3. In this study, 93 patients had a subarachnoid haemorrhage, 159 had a cerebral haemorrhage and 94 had suffered an ischaemic stroke. Among those with CVD, 33 patients had IAH. Patients with IAH had significantly lower GCS scores and significantly higher APACHE-II and modified Rankin Scale scores than patients without IAH. Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of patients with IAH required mechanical ventilation. The incidence of AKI was not significantly higher in patients with IAH. Twenty-eight patients among those with CVD died within 28 days. ICU and in-hospital mortality rates were higher and the length of ICU stay was longer among patients with IAH.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients with CVD (n=346)

| Variables | All | IAH (n=33) | Non-IAH (n=313) | p Value |

| Age (years) | 67 (58–78) | 65 (55–73) | 67 (58–78) | 0.33 |

| Male | 192 (55.5) | 21 (63.64) | 171 (54.63) | 0.322 |

| Type of CVD | 0.49 | |||

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 93 (26.9) | 11 (33.33) | 82 (26.2) | |

| Cerebral haemorrhage | 159 (46.0) | 12 (36.36) | 147 (46.96) | |

| Ischaemic stroke | 94 (27.2) | 10 (30.3) | 84 (26.84) | |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.5 (18.8–24.4) | 23.7 (21.1–26) | 21.3 (18.8–24.3) | 0.15 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 168 (146–195) | 159 (135–212) | 169 (147–193) | 0.93 |

| Pulse rate (per minute) | 81 (71.5–96) | 96 (81–109) | 80 (71–93) | <0.001 |

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.6 (36.2–37) | 36.7 (36.2–37) | 36.6 (36.2–37) | 0.82 |

| GCS score on admission | 13 (10–15) | 6 (4–13) | 14 (11–15) | <0.001 |

| APACHE-II score on admission | 11 (8–16) | 18 (12–22) | 10 (7–15) | <0.001 |

| Modified Rankin Scale score on admission | 4 (3–5) | 5 (4–5) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

| Favourable neurological condition* | 176 (50.9) | 4 (12.1) | 172 (55.0) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data on admission | ||||

| Na | 142 (140–143) | 142 (141–144) | 142 (140–143) | 0.37 |

| K | 3.8 (3.5–4.2) | 3.7 (3.3–4.1) | 3.8 (3.6–4.2) | 0.11 |

| FBS | 140.5 (117–178) | 152 (124–190) | 138 (116–176) | 0.077 |

| BUN | 15 (12–19) | 15 (12–20) | 15 (12–19) | 0.71 |

| Cr | 0.74 (0.6–0.91) | 0.75 (0.66–0.94) | 0.74 (0.6–0.9) | 0.23 |

| Maximum sodium in ICU (mEq/L) | 143 (141–145) | 154 (151–156) | 143 (141–145) | <0.001 |

| Minimum sodium in ICU (mEq/L) | 141 (139–142) | 141 (139–144) | 141 (139–142) | 0.29 |

| AKI on admission | 25 (7.2) | 5 (15.2) | 20 (6.4) | 0.064 |

| Surgery prior to ICU admission | 0.047 | |||

| Elective surgery | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Emergency surgery | 104 (30.1) | 16 (48.5) | 88 (28.1) | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.0) | 0.57 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 99 (28.6) | 27 (81.8) | 72 (23.0) | <0.001 |

| Length of ICU admissions (days) | 4 (3–6) | 8 (5–13) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

| Modified Rankin Scale at discharge | 3 (2–4) | 5 (4–6) | 3 (2–4) | <0.001 |

| All-cause hospital mortality | 29 (8.4) | 14 (42.4) | 15 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| All-cause 28-day mortality | 28 (8.1) | 13 (39.4) | 15 (4.8) | <0.001 |

Continuous data are median (IQR). Categorical data are n (%).

*A score of ≤3 indicates favourable neurological function.

AKI, acute kidney injury; APACHE, Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICU, intensive care unit.

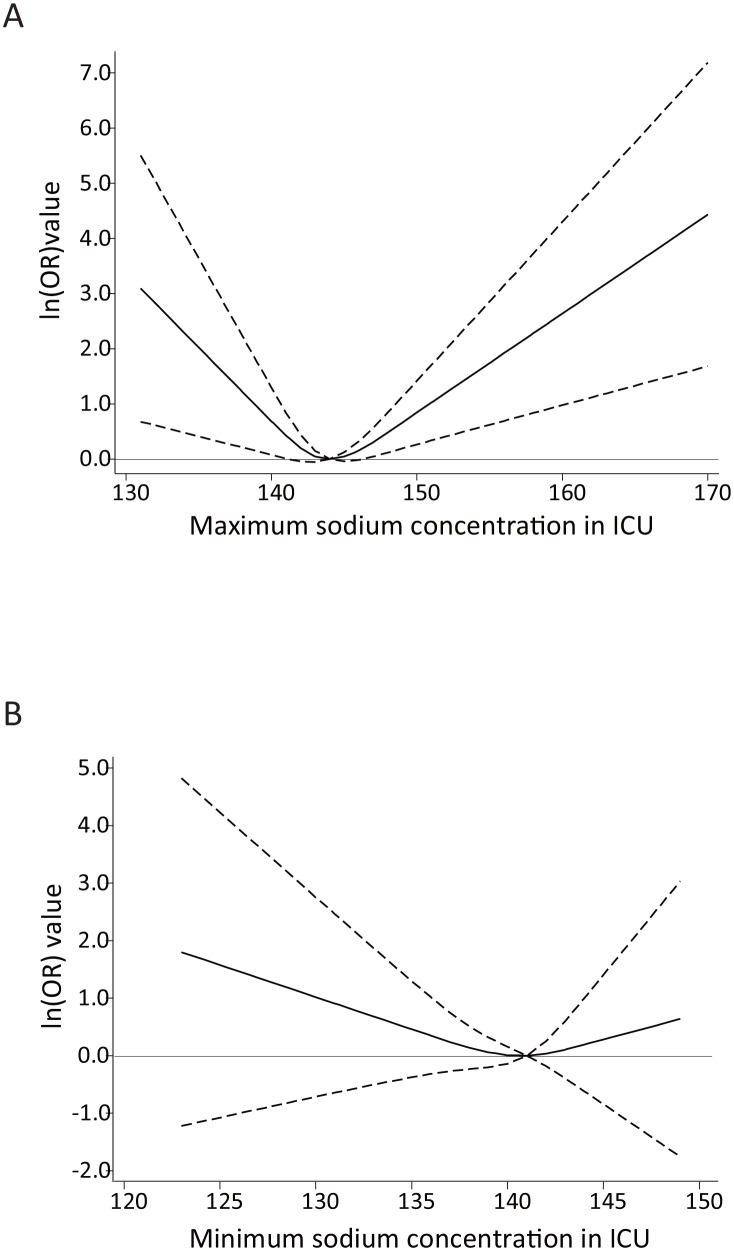

The RCS analysis showed a U-shaped association between mortality and the maximum sodium concentration (figure 3A). The curve’s nadir was between 141 and 146 mEq/L. On the other hand, the minimum sodium concentration was not significantly associated with mortality, although the RCS also demonstrated a U-shaped association (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Association between maximum and minimum sodium concentration and mortality (adjusted OR and 95% CIs) by restricted cubic spline model (three knots) in patients with cerebrovascular diseases. The dashed lines represent the 95% CIs for the spline model. (A) Maximum sodium concentration and 28-day mortality. (Reference: 144 mEq/L) The curve’s nadir was between 141 and 146 mEq/L. (B) Minimum sodium concentration and 28-day mortality. (Reference: 141 mEq/L) The spline curve was not significantly associated with mortality. ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

In this study on hypernatraemia in critically ill patients, we made two important clinical observations. First, IAH was associated with high mortality among critically ill patients, especially those with CVD. Second, using RCS analysis, a dose–response association between serum sodium concentration and mortality risk was observed, and the optimal serum sodium target concentration for patients with CVD was determined to be ≤146 mEq/L.

A prior study showed that a serum sodium concentration >160 mEq/L was an independent risk factor for mortality for patients in the neurological ICU.10 Another study showed that a serum sodium concentration >147.55 mEq/L was the optimal cut-off among patients in the neurological ICU.8 In the present study, we showed that 146 mEq/L was the upper limit of serum sodium concentration among critically ill patients with CVD admitted to ICU. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show a threshold serum sodium concentration in patients with CVD admitted to ICU.

Hypernatraemia occurs when the total amount of body sodium increases and/or total body water is lost.21 The latter factor can be caused by loss of electrolyte-free water induced by administration of osmotic diuretics and urea-induced osmotic diuresis.22 Patients in ICU are often ventilated, sedated and immobilised because of their medical condition and treatment; hence, water intake tends to be limited. There are several specific reasons for the development of hypernatraemia among patients with CVD. First, in most neurological ICUs, hypernatraemia is intentionally induced in such patients to treat brain oedema or to reduce elevated ICP.23 Evidence on the benefits of actively raising the serum sodium concentration and the active use of osmotic diuretics is lacking, especially for patients with CVD. Patients with lower GCS scores or those with clinical evidence of trans-tentorial herniation might be considered for ICP monitoring and treatment according to the guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage.24 Methods of treating elevated ICP are generally borrowed from traumatic brain injury guidelines as well. Osmotic diuretics or hypertonic saline may be used to treat acute elevations of ICP; hypertonic saline may be the more effective agent. However, this recommendation is effective only if ICP is monitored. Despite this, intravenous administration of hypertonic glycerol is commonly used in the treatment of acute stroke in Japan, often without concomitant ICP measurement.25 Actually, an osmotic diuretic (glycerol) was administered to all the patients with CVD in our cohort. According to a previous report, hypernatraemia is more likely to develop in patients who undergo osmotic diuresis.10 Second, hypothalamic or pituitary gland dysfunction is a common secondary cause for sodium or water imbalance, such as central diabetes insipidus. Hypernatraemia might reflect severity in patients with such conditions. In our cohort, it was not possible to identify from the retrospective chart review the aetiology of hypernatraemia in most cases of IAH, but some might have been iatrogenic. Initial treatment of hypernatraemia is often inadequate, and sometimes treatment is delayed.21 Thus, prevention, early detection and early treatment of IAH may be an indicator of clinical quality of care. Our findings will encourage clinicians who regularly see patients with CVD to monitor serum sodium concentrations more closely.

Hypernatraemia was shown to be associated with increased mortality among the patients with CVD. Hypernatraemia is associated with various neuromuscular manifestations, such as muscle weakness,26 that can prolong the length of ICU stay and duration of mechanical ventilation.9 These factors, in turn, can lead to infection and other complications.

In this study, we could not identify the lower limit of sodium concentration, but we showed that the lower threshold of maximum serum sodium concentration was 141 mEq/L. Hence, a serum sodium concentration <141 mEq/L may be associated with mortality in patients with CVD possibly because lower serum sodium concentration might cause brain oedema. Thus, we assume that the serum sodium concentration should be controlled at a relatively higher level.

There were several limitations to this study. First, due to the retrospective nature, the timing of and interval between examining blood samples were not decided a priori; thus, we might have missed some cases of IAH or those with lower concentrations of sodium. Second, it is possible that we underestimated the number of patients with IAH both because we excluded patients who were admitted to ICU for <2 days and because, once patients were discharged from ICU, we were not able to determine whether they developed hypernatraemia. Third, a single-centre study may be biased by local practice patterns, such as the use of osmotic diuretics or measurement of ICP. Fourth, since ICP measurement was not routinely performed, this study was unable to focus on patients with cerebral oedema. Nevertheless, osmotic diuretics such as glycerol are frequently administered in routine clinical practice in Japan. This might have contributed to hypernatraemia in some patients, leading a poor prognosis.

In the present study, we clearly demonstrated that hypernatraemia is a significant risk factor for mortality in critically ill patients, especially those with CVD. We also demonstrated that the serum sodium concentration cut-off point for increased mortality risk among patients with CVD was 147 mEq/L. These findings will be helpful for clinicians who manage critically ill patients with CVD. However, multicentre, prospective studies should be conducted to assess the usefulness of this threshold in practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the physicians and patients of Toyohashi Municipal Hospital, who contributed to this study. The authors also express gratitude to Ms Megumi Matsushita (medical assistant) for extracting the electrical data from the medical records of the study patients and to Mr Shozo Nakamura (clinical engineer), Mr Shin’ichi Miura (clinical engineer) and Mr Hironori Aoyama (clinical engineer) for offering the lists of patients who were mechanically ventilated or received renal replacement therapy.

Footnotes

Contributors: TI, MN and SM: study concept and design; TI, RN and TY: acquisition of clinical data; TI, MN, YF and SM: analysis and interpretation of data; KW, MM and TK: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; TI, MN and SM: drafting of the manuscript and statistical analysis; SM: study supervision.

Competing interests: The Department of Nephrology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, received research promotion grants from Astellas, Alexion, Otsuka, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo, Takeda, Torii, Pfizer and Mochida. The Department of Nephrology, Toyohashi Municipal Hospital, received research grants from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Otsuka, Chugai, Astellas, Takeda, Torii and Asahikasei. The Center for Advanced Medicine and Clinical Research, Nagoya University Hospital and Chubu Rosai Hospital received no research grants or donations.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of Toyohashi Municipal Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Lindner G, Funk GC, Schwarz C, et al. Hypernatremia in the critically ill is an independent risk factor for mortality. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;50:952–7. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoorn EJ, Betjes MG, Weigel J, et al. Hypernatraemia in critically ill patients: too little water and too much salt. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1562–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfm831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Donoghue SD, Dulhunty JM, Bandeshe HK, et al. Acquired hypernatraemia is an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia 2009;64:514–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darmon M, Timsit JF, Francais A, et al. Association between hypernatraemia acquired in the ICU and mortality: a cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:2510–5. 10.1093/ndt/gfq067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waite MD, Fuhrman SA, Badawi O, et al. Intensive care unit-acquired hypernatremia is an independent predictor of increased mortality and length of stay. J Crit Care 2013;28:405–12. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ni HB, Hu XX, Huang XF, et al. Risk factors and outcomes in patients with hypernatremia and sepsis. Am J Med Sci 2016;351:601–5. 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beseoglu K, Etminan N, Steiger HJ, et al. The relation of early hypernatremia with clinical outcome in patients suffering from aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014;123:164–8. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu B, Han Q, Mengke N, et al. Prognostic value of ICU-acquired hypernatremia in patients with neurological dysfunction. Medicine 2016;95:e3840 10.1097/MD.0000000000003840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang YZ, Qie JY, Zhang QH. Incidence and mortality prognosis of dysnatremias in neurologic critically ill patients. Eur Neurol 2015;73:29–36. 10.1159/000368353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aiyagari V, Deibert E, Diringer MN. Hypernatremia in the neurologic intensive care unit: how high is too high? J Crit Care 2006;21:163–72. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bihari S, Peake SL, Bailey M, et al. Admission high serum sodium is not associated with increased intensive care unit mortality risk in respiratory patients. J Crit Care 2014;29:948–54. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeon SB, Koh Y, Choi HA, et al. Critical care for patients with massive ischemic stroke. J Stroke 2014;16:146–60. 10.5853/jos.2014.16.3.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qureshi AI, Suarez JI, Bhardwaj A, et al. Use of hypertonic (3%) saline/acetate infusion in the treatment of cerebral edema: effect on intracranial pressure and lateral displacement of the brain. Crit Care Med 1998;26:440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kellum J, Lameire N, Aspelin P, et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney international supplements 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988;19:604–7. 10.1161/01.STR.19.5.604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shinohara Y, Minematsu K, Amano T, et al. Modified rankin scale with expanded guidance scheme and interview questionnaire: interrater agreement and reproducibility of assessment. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006;21:271–8. 10.1159/000091226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nichol G, Leroux B, Wang H, et al. Trial of continuous or interrupted chest compressions during CPR. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2203–14. 10.1056/NEJMoa1509139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nieboer D, Vergouwe Y, Roobol MJ, et al. Nonlinear modeling was applied thoughtfully for risk prediction: the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:426–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polderman KH, Schreuder WO, Strack van Schijndel RJ, et al. Hypernatremia in the intensive care unit: an indicator of quality of care? Crit Care Med 1999;27:1105–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindner G, Schwarz C, Funk GC. Osmotic diuresis due to urea as the cause of hypernatraemia in critically ill patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:962–7. 10.1093/ndt/gfr428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ryu JH, Walcott BP, Kahle KT, et al. Induced and sustained hypernatremia for the prevention and treatment of cerebral edema following brain injury. Neurocrit Care 2013;19:222–31. 10.1007/s12028-013-9824-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2015;46:2032–60. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Toyoda K, Steiner T, Epple C, et al. Comparison of the European and Japanese guidelines for the acute management of intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;35:419–29. 10.1159/000351754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knochel JP. Neuromuscular manifestations of electrolyte disorders. Am J Med 1982;72:521–35. 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90522-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016248supp001.jpg (167.8KB, jpg)