Abstract

Objective

Limited evidence for the optimal venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis regimen in orthopaedic trauma leads to variability in regimens. We sought to delineate patient preferences towards cost, complication profile, and administration route (oral tablet vs. subcutaneous injection).

Design

Discrete choice experiment (DCE).

Setting

Level 1 trauma center in Baltimore, USA.

Participants

232 adult trauma patients (mean age 47.9 years) with pelvic or acetabular fractures or operative extremity fractures.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Relative preferences and trade-off estimates for a 1% reduction in complications were estimated using multinomial logit modelling. Interaction terms were added to the model to assess heterogeneity in preferences.

Results

Patients preferred oral tablets over subcutaneous injections (marginal utility, 0.16; 95% CI: 0.11 - 0.21, P<0.0001). Preferences changed in favor of subcutaneous injections with an absolute risk reduction of 6.98% in bleeding, 4.53% in wound complications requiring reoperation, 1.27% in VTE, and 0.07% in death from pulmonary embolism (PE). Patient characteristics (sex, race, type of injury, time since injury) affected patient preferences (P<0.01).

Conclusions

Patients preferred oral prophylaxis and were most concerned about risk of death from PE. Furthermore, the findings estimated the trade-offs acceptable to patients and heterogeneity in preferences for VTE prophylaxis.

Keywords: thromboembolism, anticoagulation, trauma management, adult surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study quantifies patient preferences for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a high-risk and often difficult to research population.

The results provide valuable benefit–risk trade-offs estimates to guide clinicians in a common decisional dilemma.

High face validity in the choice sets is demonstrated by the directionality, magnitude and consistency of the responses.

The high response rate captured in this prospective study reduces response bias present in other survey methods.

The choice sets presented to respondents were hypothetical scenarios, and the respondent’s actual choices may be different.

Introduction

Traumatic injury is a well-described risk factor for the development of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The incidence of VTE among trauma patients ranges from 20% to 90% without any preventative measure.1 In addition, pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third most common cause of death in patients who survive the first 24 hours following injury.1–4 Orthopaedic trauma patients in particular have several well-known risk factors for VTE placing them at exceptionally high risk.2 5–8 Fortunately, chemoprophylaxis has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of VTE in this population.9 However, controversy exists as to the optimal VTE prophylaxis regimen in orthopaedic trauma patients.10–15

For many orthopaedic populations, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) and the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma recommend enoxaparin (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH)) by subcutaneous injection for VTE prophylaxis, but recent studies show that acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), an oral tablet, may be an equally effective alternative with lower risk of bleeding complications.10–15 However, only limited data are available specific to orthopaedic trauma patients who may have even higher risk for both VTE events and bleeding.16 The Orthopaedic Trauma Association Evidence Based Quality Value and Safety Committee highlights variability in prescribed regimens due to the poor scientific support for various regimens and emphasises the need for guidelines to improve patient care.17

The CHEST guidelines emphasise the need for systematic reviews of patient values and preferences when creating guidelines for specific populations.18 Creation of guidelines requires making risk and benefit trade-offs, and patient values regarding VTE prophylaxis depend on the health outcomes considered. Furthermore, defining the heterogeneity of preferences in this patient population is necessary to provide valuable individualised VTE prevention options. Implementing guidelines that consider patient preferences may increase patient satisfaction with and improve adherence to clinical treatments.19 Patient medication refusal is a leading cause of non-administration of VTE prophylaxis in inpatients, and missed doses are highly associated with increased VTE incidence.20–22 In a study of medical and surgical patient preferences for VTE prophylaxis regimens, the majority of patients preferred oral administration over subcutaneous injection if all other factors were equal.23 Patients who preferred subcutaneous administration presumed a faster onset of action and were less likely to refuse administration.

Existing VTE prevention studies do not evaluate patient preferences, investigate acceptable trade-offs of the risks and benefits of those medications or determine heterogeneity in preferences based on demographic and clinical characteristics. The purpose of this study was to elicit the preferences of orthopaedic trauma patients toward currently available VTE prophylaxis, examine acceptable trade-offs of the potential complications related to those mediations and determine heterogeneity in preferences among patient subgroups.

Methods

A discrete choice experiment (DCE) was prospectively administered to orthopaedic trauma patients at a level 1 trauma centre. DCEs are a quantitative technique used to measure individual preferences in a variety of healthcare settings by administering surveys that ask individuals to choose the best option between two or more hypothetical scenarios or choice sets.24–26 Options are described with a fixed set of attributes levels that vary in each scenario. The data collected can be used to assess the relative importance of each attribute and acceptable trade-offs among attributes. An estimate of preference can be described as the marginal utility for a given attribute level. Marginal utility can be positive or negative, with numbers farther from zero indicating a stronger preference. Monetary costs can be included to produce willingness-to-pay estimates.

Study setting and population

This study was conducted at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Centre in Baltimore, Maryland, and received prior approval by the institutional review board at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. All adult (> 18 years) patients treated with pelvic or acetabular fractures or an operative extremity fracture were assessed for eligibility from November 2015 to February 2016. Patients who were unable to consent due to intubation or altered mental status and non-English-speaking patients were excluded. On written consent, patients were enrolled in the study as inpatients or at an outpatient follow-up appointment within 4 months from their initial admission for their injury.

Study design

The attributes and their corresponding levels were selected based on a literature review, patient interviews, expert consultation and a retrospective review of patient outcomes. Medication attributes used in the DCE included medication administration route (oral tablet vs subcutaneous injection), cost, possible side effects including bruising or stomach pain, risk of having a bleeding complication that requires a blood transfusion, risk of having a wound complication that requires another operation, risk of VTE requiring therapeutic anticoagulation for 6 months and risk of death due to PE. These attributes were chosen to reflect medication qualities that patients are aware of when taking medications (route, cost, side effects) and clinically important outcomes. Values for these attributes were based on available literature and clinical experience with two commonly prescribed VTE prophylaxis medications in this population: LMWH (a subcutaneous injection) and aspirin (an oral tablet). Attributes were not reflective of other oral anticoagulants because those medications are typically used for treatment of VTE events rather than prevention and the focus of this DCE is preferences for prophylaxis administered to prevent VTE events.

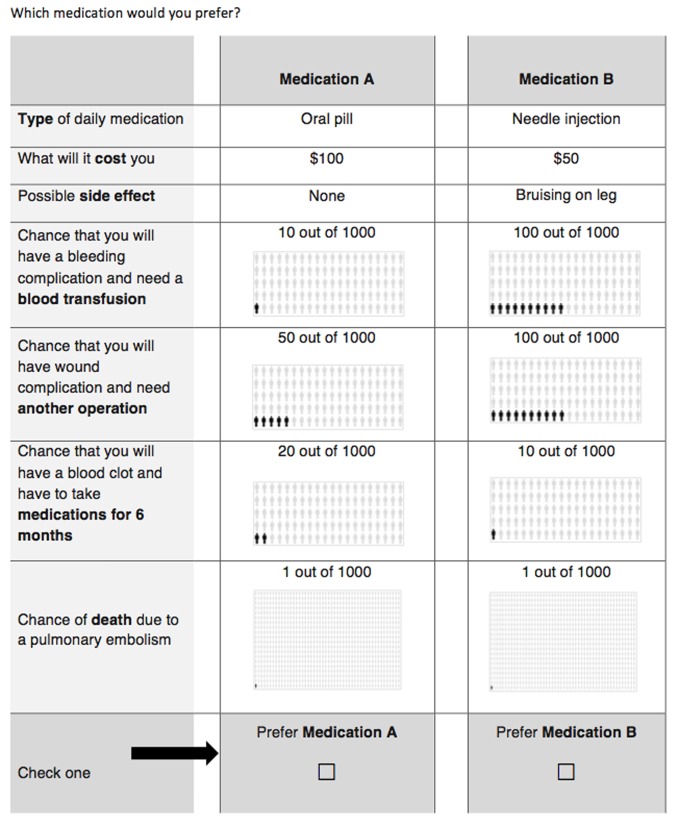

Forty choice sets were developed using a Bayesian D-optimal design with JMP V.12 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) to ensure maximum variation in attribute comparison. The 40 choice sets were then randomly divided into four surveys, each with 10 choice sets, to minimise respondent burden. As documented by Sandor et al,27 using heterogeneous designs produce substantial improvements in efficiency over a single survey and provide more precision in estimating true parameters. Each choice set compared two hypothetical VTE prophylaxis medications described by their attributes (figure 1). Patients were randomly assigned one of the four self-administered surveys. A member of the research staff was available for questions as the study participant completed the survey. Demographic data including age, sex, race (as defined by the participant), type of injury, Injury Severity Score, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, income, health insurance status, days on prophylaxis and timing of recruitment (inpatient vs outpatient) were collected from both the survey and the medical record. The type of VTE prophylaxis was not collected as part of the study. However, at the time of the study, VTE prophylaxis by LMWH was the standard hospital protocol, and it is reasonable to assume that this was prescribed to all study participants unless there was a contraindication.

Figure 1.

Sample question from the discrete choice experiment survey administered to participants. In each question, the values for each hypothetical medication are varied.

The target sample size for this study was derived by the Rule of Thumb calculation described by Orme and our a priori decision to conduct multiple subgroup analyses.28 Based on this calculation,28 we determined that a sample of 25 study participants would be required in each possible subgroup category for adequate statistical power. Given known proportions of admission data for this population, a sample size exceeding 200 participants was required to adequately assess heterogeneity in preferences, particularly on sex, race and health insurance status.

Data analysis

Data collected through the DCE survey allow the quantification of and statistical inference about the relative importance of VTE prophylaxis medication attributes. A multinomial logit model,29 30 with effect coding, was used to estimate patient preferences using marginal utility, willingness to pay (WTP) and acceptable trade-off estimates for a 1% reduction in VTE complications or side effects. Marginal utility is a measure of patient preference, with the estimate signifying the strength and direction of one’s preference toward the attribute. With this analysis, we are able to determine the relative magnitude of patient preferences to avoid VTE-related complications in association with their medication choice. Preference heterogeneity was subsequently assessed by adding an interaction term into the model with a priori determined variables of interest. These variables included age (categorised as <40, 40–59, >60), sex, race, ASA status (≤2 vs >2), the location of primary injury (upper extremity vs lower extremity), household income (categorised as ≤$20 000, $20 000–$49 999, $50 000–$74 999, ≥$75 0000), health insurance status (any vs none) and the location of recruitment. All data analysis was conducted using the Choice Modelling platform in JMP V.12.

Results

Of the 310 patients screened for participation, 50 were ineligible (40 unable to consent due to altered mental status, eight non-English speaking, two contraindicated for VTE prophylaxis) and 28 (11%) patients refused participation. Of the 232 patients included in the analysis, the mean age was 47.9 years, with 56.9% male, and 66.8% were white. The majority of participants had a lower extremity injury (83.6%), with a mean injury severity score of 11.7, and were fully insured (83.1%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of orthopaedic fracture participants (n=232)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) |

| Male, n (%) | 132 (56.9) |

| Age, y | 47.9 (17.7) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 155 (66.8) |

| Black | 62 (26.7) |

| Other | 8 (3.4) |

| Hispanic | 7 (3.0) |

| Primary orthopaedic injury, n (%) | |

| Lower extremity | 194 (83.6) |

| Upper extremity | 38 (16.4) |

| ASA,* n (%) | |

| 1 | 21 (9.1) |

| 2 | 117 (50.4) |

| 3 | 81 (34.9) |

| 4 | 11 (4.7) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.9) |

| Injury Severity Score | 11.7 (6.7) |

| Income, US$, n (%) | |

| <$10 000 | 46 (19.8) |

| $10 000–$19 999 | 20 (8.6) |

| $20 000–$34 999 | 35 (15.1) |

| $35 000–$49 999 | 24 (10.3) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 26 (11.1) |

| $75 000–$100 000 | 24 (10.3) |

| >$100 000 | 35 (15.1) |

| Unknown | 22 (9.5) |

| Health insurance, n (%) | |

| Fully insured | 193 (83.1) |

| Partially insured | 12 (5.2) |

| Uninsured | 24 (10.3) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.3) |

| Timing of recruitment, n (%) | |

| Inpatient | 78 (33.6) |

| Outpatient | 154 (66.4) |

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification system for assessing preoperative patient fitness.

*Injury Severity Score is a well-validated score that assesses trauma severity based on a consensus-derived severity score that classifies each injury from six body regions (head or neck, face, chest, abdomen, extremities and external). A score greater than 15 is commonly referred to as a major trauma (or polytrauma).

Patients most strongly preferred a reduction in risk of death by PE (marginal utility, 4.57; p<0.0001), distantly followed by a reduction in the risk of VTE requiring therapeutic anticoagulation, wound complications requiring another surgery and bleeding complications requiring a transfusion (table 2). Patients were willing to pay $1686.90 for a 1% absolute reduction in risk of death due to PE compared with $92.29 or less for a 1% absolute reduction in any of the other measured outcome variables. Patients also preferred to take oral tablets (marginal utility, 0.16; p<0.0001) and were willing to pay $117.45 to receive prophylaxis via oral route over subcutaneous injection. Possible medication side effects, such as stomach pain or bruising, did not significantly influence patient preferences (p>0.1).

Table 2.

Patient preferences and valuation of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis attributes

| Attribute | Level | Marginal utility | 95% CI | WTP | p Value |

| Route | Oral tablet | 0.16 | 0.11 to 0.21 | $117.45 | <0.0001 |

| Subcutaneous injection | −0.16 | −0.21 to −0.11 | – | – | |

| Side effects | Bruising on leg | −0.04 | −0.11 to 0.02 | -$45.94 | 0.11 |

| Stomach pain | −0.04 | −0.12 to 0.04 | -$44.08 | – | |

| No side effects | 0.08 | 0.003 to 0.16 | $45.08 | – | |

| Bleeding complications requiring transfusion | Reduce risk by 1% | 0.05 | 0.04 to 0.05 | $16.83 | <0.0001 |

| Wound complications requiring another surgery | Reduce risk by 1% | 0.07 | 0.06 to 0.08 | $25.91 | <0.0001 |

| Blood clot requiring long-term medication | Reduce risk by 1% | 0.25 | 0.15 to 0.36 | $92.29 | <0.0001 |

| Death due to PE | Reduce risk by 1% | 4.57 | 3.26 to 5.89 | $1686.90 | <0.0001 |

| Cost | $10 increase | −0.03 | −0.04 to −0.02 | Reference | <0.0001 |

Marginal utility quantifies the additional satisfaction gained by the patient for each described attribute/level. Negative marginal utility values signify an aversion to or dissatisfaction with the described attribute/level. All risk reductions are absolute. Willingness to pay for the route and side effect category is based on the full treatment course, not per dose. Willingness to pay for all other attributes is based on the incremental change in level.

PE , pulmonary embolism; WTP, willingness to pay.

To change patient preference in favour of subcutaneous injections requires a 6.98% absolute reduction in the risk of bleeding complications requiring transfusion, a 4.53% absolute reduction in the risk of wound complications requiring reoperation and a 1.27% absolute reduction in risk of VTE requiring therapeutic anticoagulation (table 3). In contrast, only a 0.07% absolute reduction in risk of death due to PE was needed to change patient preference.

Table 3.

The absolute risk reduction (ARR) of a potential complication that a patient would be willing to accept to change their route preference from oral to subcutaneous injection prophylaxis

| Attribute | Acceptable ARR trade-off |

| Bleeding complications requiring transfusion | 6.98% |

| Wound complications requiring another surgery | 4.53% |

| Blood clot requiring long-term medication | 1.27% |

| Death due to PE | 0.07% |

ARR, absolute risk reduction; PE, pulmonary embolism.

In our subgroup analyses examining heterogeneity in preferences, patients who were female, white or had lower extremity injuries demonstrated significantly stronger preference for oral VTE prophylaxis over subcutaneous injections (p<0.05) (table 4). Patients with upper extremity injuries valued a reduction in risk of bleeding complications more than patients with lower extremity injuries (p=0.01). Patients who were recruited as an inpatient valued a reduction in risk of wound complications requiring reoperation more than patients who were recruited from the outpatient clinic (p<0.01). There were no other significant associations between the tested covariates and our included VTE prophylaxis attributes.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis quantifying heterogeneity in patient preferences

| Attribute | Level | Subgroup | Marginal utility | 95% CI | WTP | p Value |

| Route | Take oral tablet over subcutaneous injection | Sex (female) | 0.07 | 0.02 to 0.11 | $201.24 | <0.01 |

| Sex (male) | −0.07 | −0.11 to −0.02 | $66.79 | |||

| Race (white) | 0.09 | 0.03 to 0.14 | $182.23 | <0.01 | ||

| Race (black) | −0.09 | −0.14 to −0.03 | $18.48 | |||

| Injury (lower extremity) | 0.08 | 0.02 to 0.15 | $132.38 | 0.01 | ||

| Injury (upper extremity) | −0.08 | −0.15 to −0.02 | $18.98 | |||

| Bleeding complications requiring transfusion | Reduce risk by 1% | Injury (lower extremity) | −0.02 | −0.03 to −0.003 | $14.50 | 0.01 |

| Injury (upper extremity) | 0.02 | 0.003 to 0.03 | $32.04 | |||

| Wound complications requiring another surgery | Reduce risk by 1% | Recruitment (inpatient) | 0.02 | 0.003 to 0.03 | $46.32 | <0.01 |

| Recruitment (outpatient) | −0.02 | −0.03 to −0.003 | $20.24 |

Marginal utility quantifies the additional satisfaction gained by the patient for each described attribute/level. Negative marginal utility values signify an aversion to or dissatisfaction with the described attribute/level. All willingness to pay values are presented in reference to a less preferred option. For example, both females and males prefer oral tablets compared with a subcutaneous injection. However, females are willing to pay more for an oral tablet over a subcutaneous injection than males are willing to pay for that same trade-off (oral tablet over subcutaneous injection). Willingness to pay values for attributes with continuous levels estimate the willingness to pay for an additional 1% absolute reduction in risk.

WTP, willingness to pay.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies,23 our study demonstrates a strong patient preference for oral VTE prophylaxis over subcutaneous injection when all other relevant attributes are equal. However, patients only required a small reduction in the absolute risk of death due to PE to change their preference in favour of a subcutaneous injection. When choosing between VTE prophylaxis regimens, patients most valued (in order): risk of death due to PE, risk of VTE requiring therapeutic anticoagulation, risk of wound complications requiring reoperation and risk of bleeding complications requiring transfusion. A defined reduction in any of these outcomes could change patient preference to favour the subcutaneous injection route. In addition, underlying patient factors such as sex, race, type of injury and inpatient status led to significant heterogeneity in patient preferences.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the weight of patient-valued outcomes regarding potential risks and complications of VTE prophylaxis. The study also determined patient characteristics associated with heterogeneity in their preferences. Previous studies have shown that patient refusal is a common reason for missed VTE doses and increases the risk of a VTE event.20–23 Patient preference for oral medications is also well documented.23 31 Our study also demonstrates a strong preference for oral medications, but our results show that this preference can change if the risk of the aforementioned patient-important outcomes is high enough. Patients were particularly concerned about the risk of death due to PE, requiring only a 0.07% absolute reduction in risk of death to change patient preference in favour of a subcutaneous injection. In addition, only relatively small reductions in the risk of other outcomes were required to change patient preference. Furthermore, the preference for route varied significantly depending on the patient’s sex, race, type of injury and inpatient status.

While the design of the DCE enables the assessment of risk–benefit trade-offs among subgroups, it does not allow for qualitative analysis of patient preferences. As a result, we are only able to speculate as to why patients valued certain outcomes more than others. In addition, the choice sets were hypothetical scenarios, and patient’s actual choices may be different. The greater value placed on risk of death due to PE compared with other outcome measures could be a result of death being the easiest outcome variable for the average patient to understand. We were unable to control for patient disposition in our analysis (home vs rehab), but we did compare responses of inpatients to outpatients. Patients who were recruited as an inpatient were more concerned about the risk of reoperation than patients recruited as outpatients, potentially because their injury and initial operation were more recent in their memory. In addition, study participants had varying lengths of VTE prophylaxis prescribed at time of recruitment, and some patients were closer to time of injury and initial operation than others, although, when assessed, time since injury did not affect patient preferences.

Some participants had personal experience with one or more of the measured outcomes, while others had no history of complications, which we were unable to control for in our final analysis. In the same manner, the mean Injury Severity Score (ISS) of our sample was 11.7, likely as a result of many patients having isolated orthopaedic injuries as well as more severely injured patients not having the mental capacity to complete the survey. ISS ranged from 4 to 34, but there is the possibility that our results may suffer from some respondent bias if trying to extrapolate to a more severely injured population. Lastly, we did not collect data on patient education level which could affect the patient’s understanding of certain outcomes; however, income and insurance level may be surrogate markers for education and were included in the analysis.

In the current era of patient-centred healthcare, it is important that we consider all outcomes that patients value and the heterogeneity in those preferences when conducting clinical comparative effectiveness research and when making clinical guidelines in order to improve healthcare delivery and reduce cost.19 32 33 Our data demonstrate that orthopaedic trauma patients prefer VTE prophylaxis by oral tablet to prophylaxis by subcutaneous injection when all other relevant attributes are equal. However, the risk of death due to PE is the dominant concern when choosing a regimen. Our study is the first to document the value patients place on various clinically important outcomes related to VTE prophylaxis. In addition, we define the underlying patient factors that contribute to variation in VTE prophylaxis preferences with risk–benefit trade-offs among subgroups in this important area of ongoing debate. In the era of patient-centred healthcare, future studies and clinical guideline recommendations comparing available VTE prophylaxis regimens should focus on the outcomes most important to patients and incorporate patient trade-off estimates to ensure their work is reflective of patient preferences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the respondents for their time and participation in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: BH contributed to the literature search, study design, data collection, data interpretation, writing and critical revision. NNO contributed to the literature search, study design, data analysis, data interpretation, writing and critical revision. CDM contributed to the data interpretation and critical revision. DS, TTM, HJ, RVO and GPS contributed to the literature search, study design, data interpretation and critical revision. RC contributed to the study design, data analysis, data interpretation and critical revision. All authors have approved the final version of the article submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Research reported in this manuscript was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (PCS-1511-32745). The views in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its board of governors or methodology committee.

Competing interests: CDM reports consulting with Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen/J&J, Mundipharma, NovoNordisk and Pfizer and receiving grants from Bayer, Novartis, Merck and Pfizer. TTM receiving grants from the US Air Force and serves as an advisor for Decisio Health. TTM reports consulting with Stryker, Globus and Smith & Nephew, being paid for expert testimony from various law firms and payment for lectures by the Maine Review Course. RVOT reports consulting with Coorstek (Zimmer) and Smith & Nephew and receiving royalties from Coorstek. GPS reports payments for presenting by Zimmer Biomet. No other disclosures were reported.

Patient consent: Obtained

Ethics approval: University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Shackford SR, Moser KM. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in trauma patients. J Intensive Care Med 1988;3:87–98. 10.1177/088506668800300205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geerts WH, Code KI, Jay RM, et al. . A prospective study of venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1601–6. 10.1056/NEJM199412153312401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Malley KF, Ross SE. Pulmonary embolism in major trauma patients. J Trauma 1990;30:748–50. 10.1097/00005373-199006000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sevitt S, Gallagher N. Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A clinico-pathological study in injured and burned patients. Br J Surg 1961;48:475–89. 10.1002/bjs.18004821103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shackford SR, Davis JW, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, et al. . Venous thromboembolism in patients with major trauma. Am J Surg 1990;159:365–9. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81272-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abelseth G, Buckley RE, Pineo GE, et al. . Incidence of deep-vein thrombosis in patients with fractures of the lower extremity distal to the hip. J Orthop Trauma 1996;10:230–5. 10.1097/00005131-199605000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rogers FB. Venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: a review. Surgery 2001;130:1–12. 10.1067/msy.2001.114558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hak DJ. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma and long bone fractures. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2001;7:338–43. 10.1097/00063198-200109000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stannard JP, Lopez-Ben RR, Volgas DA, et al. . Prophylaxis against deep-vein thrombosis following trauma: a prospective, randomized comparison of mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:261–6. 10.2106/JBJS.D.02932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. . American College of chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice guidelines . Prevention of VTE in orthopaedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):e278S–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hill J, Treasure T. National Clinical Guideline Centre for Acute and Chronic conditions. reducing the risk of Venous thromboembolism in patients admitted to hospital: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2010;340:c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mont MA, Jacobs JJ, Boggio LN, et al. . Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011;19:768–76. 10.5435/00124635-201112000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson DR, Dunbar MJ, Bohm ER, et al. . Aspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:800–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sahebally SM, Healy D, Walsh SR. Aspirin in the primary prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in surgical patients. Surgeon 2015;13:348–58. 10.1016/j.surge.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, et al. . Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med 2014;9:579–85. 10.1002/jhm.2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barrera LM, Perel P, Ker K, et al. . Thromboprophylaxis for trauma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:CD008303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sagi HC, Ahn J, Ciesla D, et al. . Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in orthopaedic trauma patients: a survey of OTA member practice patterns and OTA expert panel recommendations. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:e355–62. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacLean S, Mulla S, Akl EA, et al. . Patient values and preferences in decision making for antithrombotic therapy: a systematic review: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chestchest 2012;141(2 Suppl):e1S–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krahn M, Naglie G. The next step in guideline development: incorporating patient preferences. JAMA 2008;300:436–8. 10.1001/jama.300.4.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shermock KM, Lau BD, Haut ER, et al. . Patterns of non-administration of ordered doses of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: implications for novel intervention strategies. PLoS One 2013;8:e66311 10.1371/journal.pone.0066311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haut ER, Lau BD, Kraus PS, et al. . Preventability of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. JAMA Surg 2015;150:912–5. 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Louis SG, Sato M, Geraci T, et al. . Correlation of missed doses of enoxaparin with increased incidence of deep vein thrombosis in trauma and general surgery patients. JAMA Surg 2014;149:365–70. 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong A, Kraus PS, Lau BD, et al. . Patient preferences regarding pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med 2015;10:108–11. 10.1002/jhm.2282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. . Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011;14:403–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luyten J, Kessels R, Goos P, et al. . Public preferences for prioritizing preventive and curative health care interventions: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health 2015;18:224–33. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ 2000;320:1530–3. 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sándor Z, Wedel M. Heterogeneous Conjoint Choice designs. Journal of Marketing Research 2005;42:210–8. 10.1509/jmkr.42.2.210.62285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Orme B. Sample size issues for conjoint analysis studies. Sequim: Sawtooth Software Technical Paper, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McFadden D. Econometric models for probabilistic choice among products. J Bus 1980;53:S13–29. 10.1086/296093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Carson RT. Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. Journal of Choice Modelling 2010;3:57–72. 10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70014-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. . Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:269–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tunis SR, Clarke M, Gorst SL, et al. . Improving the relevance and consistency of outcomes in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res 2016;5:193–205. 10.2217/cer-2015-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Price-Haywood EG. Clinical comparative effectiveness research through the lens of healthcare decision makers. Ochsner J 2015;15:154–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.