Abstract

Introduction

Several techniques have been proposed to manage dental fear/dental anxiety (DFA) in children and adolescents undergoing dental procedures. To our knowledge, no widely available compendium of therapies to manage DFA exists. We propose a study protocol to assess the evidence regarding pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to relieve dental anxiety in children and adolescents.

Methods and analysis

In our systematic review, we will include randomised trials, controlled clinical rials and systematic reviews (SRs) of trials that investigated the effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to decrease dental anxiety in children and adolescents. We will search the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects=, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and the Web of Science for relevant studies. Pairs of review authors will independently review titles, abstracts and full texts identified by the specific literature search and extract data using a standardised data extraction form. For each study, information will be extracted on the study report (eg, author, year of publication), the study design (eg, the methodology and, for SRs, the types and number of studies included), the population characteristics, the intervention(s), the outcome measures and the results. The quality of SRs will be assessed using the A Measurement Tool to Assess Reviews instrument, while the quality of the retrieved trials will be evaluated using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions criteria.

Ethics and dissemination

Approval from an ethics committee is not required, as no participants will be included. Results will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Keywords: oral medicine, anxiety disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We anticipate our study to be the first comprehensive systematic reviews concerning both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to manage dental fear/dental anxiety (DFA) in children and adolescents undergoing dental procedures as well as an assessment of the quality of evidence of the included studies will be performed in this review.

The findings of this study have the potential to inform and influence clinical decision-making and guideline development.

There may be language bias as only studies published in English will be included.

Significant heterogeneity is expected due to the different types of interventions and the different modality, frequency of administration of the interventions.

Introduction

Dental fear (DF) usually indicates a normal unpleasant emotional reaction to specific threatening stimuli occurring in situations associated with dental treatment, while dental anxiety (DA) is an excessive and unreasonable negative emotional state experienced by dental patients.1 These psychological states consist of anxiety that something frightful is going to happen in relation to dental treatment.1 2 In the scientific literature DF and DA often are used indistinctly.1 In this review, will the term dental fear and anxiety (DFA) will be used to indicate strong negative emotions associated with dental treatment among children and adolescents. DFA has been identified as a common and significant problem in children and adolescents, with a mean prevalence ranging between 10% and 20%, being particularly high in the earliest ages.2 Failure to attend dental clinics is considered the major consequence to DFA.3 4 There is general agreement that the aetiology for dental anxiety is multifactorial, hence is difficult to propose a single therapy for its management. In addition, the occurrence of anxiety during dental treatment may result in loss of time, unsatisfactory outcome or failure of performing dental procedures.5–9 Adequate evaluation of general patient characteristics, recognising a possible source of anxiety as well its intensity can help the dentist to plan the management. Three measures are generally used to assess the level of DFA: (1) ‘psychometric assessment’ in which the children or one of their parents have to complete a questionnaire, usually before the treatment, to indicate the child’s level of anxiety associated with various common dental situations; (2) ‘physiological response analysis’ in which the variations linked to the manifestation of anxiety are measured, such as salivary cortisol levels and (3) ‘projective test’ based on psychological interpretation of children pictures concerning elements of dental setting.10–12

To allay the anxiety of children and increase the compliance to dental treatment, various techniques have been proposed, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological.13 Pharmacological interventions include the benzodiazepines, nitrous oxide and other agents that are delivered by a large variety of means, frequency, timing and combinations.14 General anaesthesia has been proposed as an alternative pharmacological intervention though now it is discouraged due to possible but rare risk of death and high cost since it requires the involvement of specialist facilities including professionals such as anaesthetists and specialist nurses.14–16

Non–pharmacological interventions, can be theoretically grouped into: (1) communication skills, rapport and trust building; (2) behaviour modification techniques; (3) cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and (4) physical restraints.13 The first group of non-pharmacological interventions include verbal and non-verbal communication.17 Behaviour modification techniques represent a heterogeneous group of interventions such as tell show do, voice control, signalling, distraction, hypnosis and others.17–20 The CBT aims to modify and restructure the child’s negative beliefs and expectations to reduce their dental anxiety and improve the control of negative thoughts. The use of CBT has been shown to be effective in the control of extremely anxious and phobic subjects.13 Finally, physical restraints is a technique used in some countries and is characterised by a forced restricted movement of the patient. This approach should be limited to rare, critical clinical situations, where there are no other possibilities of intervention.21

While many examples of approaches and techniques for the management of DFA exist, to date evidence concerning any collection of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies for the management of DFA in children and adolescents has not been sufficiently addressed. This might contribute to the underuse of effective techniques to reduce DFA in clinical practice. Hence, to fill this gap, we propose a review for the assessment of the evidence of all pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for relieving anxiety in children and adolescents undergoing dental procedures.

Objective

The primary objective of this review is to assess the efficacy and safety of using pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of dental anxiety in paediatric patients undergoing dental procedures.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Systematic reviews (SRs) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled clinical trials (CCTs), RCTs and CCTs assessing the effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions aimed to control the levels of dental anxiety in children and adolescents will be considered. Publications written in languages other than English language will be excluded.

Types of participants

The population of interest will consider children and adolescents between the ages of 0 and 18 years attending a dental centre for dental visit/treatment.

Types of interventions

Any pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention aimed at managing levels of DFA. Furthermore, children and adolescents, receiving a mixed intervention will be included. We will consider studies comparing the intervention(s) of interest versus the following controls:

No intervention or placebo;

Other type of pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Anxiety levels measured by a validated tool (physiological measure, psychometric questionnaire and/or projective test);

Completion of dental treatment (yes/no);

Adverse events associated with the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Dental avoidance;

Operator preference/fatigue in operator;

Patient satisfaction;

Parental satisfaction;

Time taken to undertake the intervention;

Duration of dental treatment.

Search methods for identification of SRs

We will identify all relevant SRs providing data on the issue, published between 1990 and 31 December 2016. Publications written in a language other than English will not be included.

Electronic searches

To identify the records of interest we will use the following terms to formulate specific search strategy: dental fear, dental anxiety, dental phobia and odontophobia.

The search string will be used in the following databases:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews;

Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects;

PubMed;

Embase;

Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection;

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL);

Web of Science.

All eligible studies retrieved from the searches will be checked for relevant references.

Study selection

Two authors will independently assess SRs for inclusion on the basis of title and abstract. Two criteria will be considered for further evaluation of an abstract record: (1) a publication defined as a review or meta-analysis and (2) the mention of any pharmacological or non-pharmacological intervention for dental anxiety management. Subsequently, full texts of relevant abstracts will be obtained and screened to identify SRs of interest based on the following inclusion criteria:

The use of at least one medical literature database (eg, Medline);

The inclusion of at least one primary study (randomised trials or CCTs);

The use of at least one pharmacological or non-pharmacological intervention for the management of dental anxiety in children and adolescents between the ages of 0 and 18 years old attending a dental centre for dental visit/treatment.

Two independent authors will judge their suitability for inclusion against the inclusion criteria. Disagreement will be resolved by discussion and, if necessary, by a third independent reviewer.

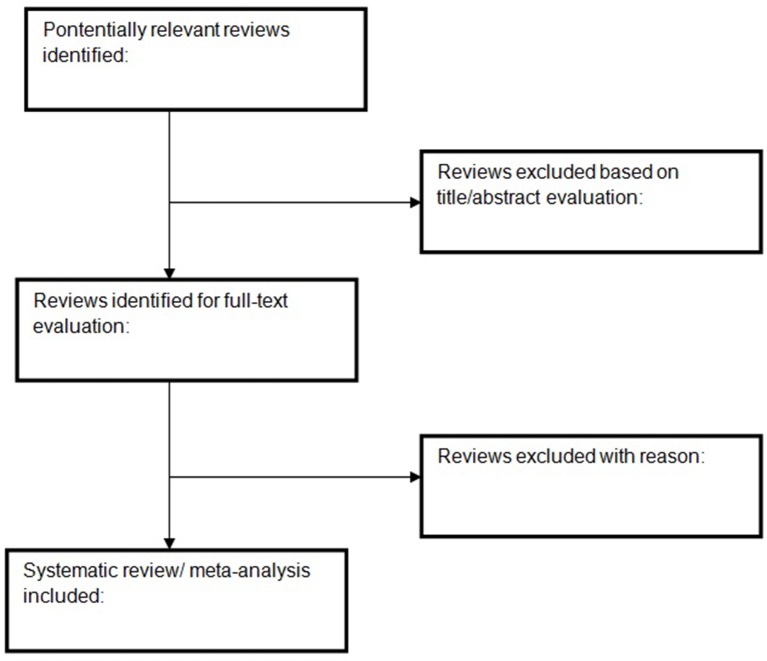

The process of study screening process will follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram guidelines (figure 1).22 Excluded studies will be listed in a table together with reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for systematic reviews.

Data extraction and management

Data from included SRs will be extracted by two review authors independently and in duplicate extract. Any disagreements will be resolved by a consensus and, where necessary by the involvement of a third review author.

The data extracted will provide information on the following items: study information (author, year of publication, country), database used, types and number of studies included, population characteristics, intervention(s) description, control or comparison intervention, outcome(s) measures used and results. If the review contains meta-analyses, we will extract pooled results. Funding and author’s conflict of interest will be extracted, too.

Where information is missing, we will contact trial authors to obtain further data.

Search methods for identification of RCTs and CCTs

We will attempt to identify any relevant clinical trial providing data on the efficacy and safety of interventions to decrease DFA published in English between 1990 and 31 December 2016. We will exclude papers written in a language other than English.

Electronic searches

To identify the records of interest we will use the following terms to formulate specific search strategy: dental fear, dental anxiety, dental phobia and odontophobia.

This search strategy will be used in the following database:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials;

PubMed;

Embase;

Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection;

CINAHL;

Web of Science.

Searching other resources

We will check the bibliographies of included studies to identify further relevant studies.

Study selection

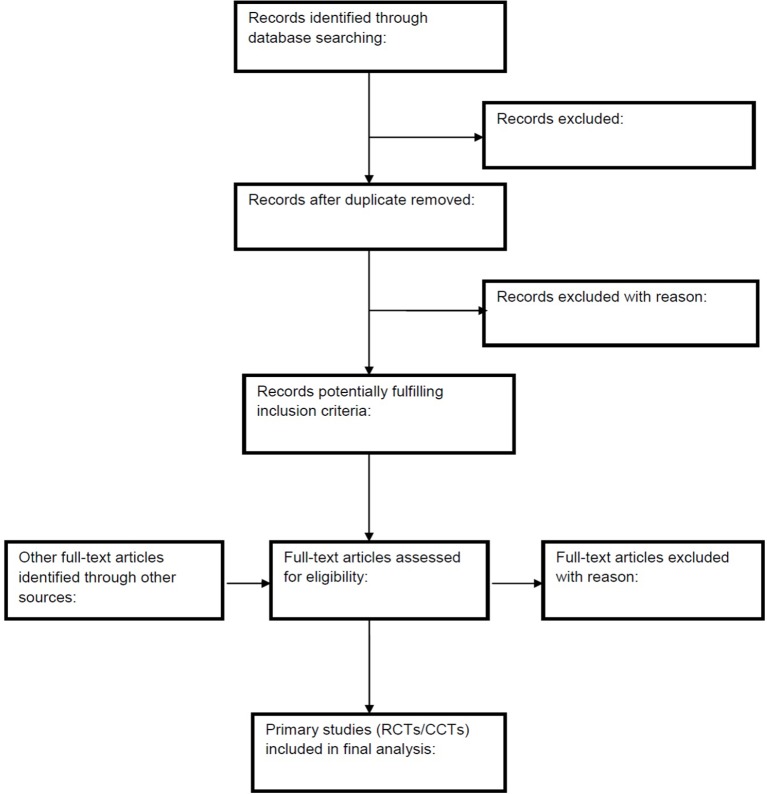

Titles and abstracts will be independently screened by two review authors to select potentially relevant studies. Full text of these studies will be identified and their inclusion evaluated independently and in duplicate. Any possible discrepancies regarding the eligibility of these studies will be resolved by discussion and, where necessary, with the involvement of a third review author. Primary studies already contained in the included SRs will not be considered. The process of identification of selection and evaluation of published study selection will be presented following the PRISMA flow diagram (figure 2).22

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for RCTs and CCTs. CCT, clinical controlled trials; RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

Excluded studies at this stage will be listed in a table along with detailed information on reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two researchers will independently and in duplicate extract data from primary studies, and disagreements will be resolved by consensus or where necessary with the involvement of a third review author.

The data extracted will provide information on the following study characteristics: study information (author, year of publication, country), study design, population characteristics, intervention(s) description, control or comparison intervention, outcome(s) measures used and results. Funding and author’s conflict of interest will also be extracted.

Assessing the methodological quality of evidence in included studies

Quality of evidence for included SRs

We will assess the methodological quality of each systematic review using the A Measurement Tool to Assess Reviews (AMSTAR) instrument to appraise the quality.23 AMSTAR appraises the quality of reviews using the following 11 items: duplicate study selection and data extraction, comprehensive searching of the literature, presentation of a list of included and excluded studies, presentation of characteristics of included studies, evaluation of methodological quality of included studies, appropriate methods for pooling results of studies and for evaluation of publication bias and consideration of conflict of interest statement.23 Two reviewers will independently assess the quality of the SRs and disagreement will be resolved by consensus. Where there are multiple reviews that answer the same clinical question, the most updated reviews with the highest score will be considered in the evidence retrieval and evaluation.

Quality of evidence for RCTs and CCTs

The quality of evidence for retrieved RCTs and CCTs will be assessed using the criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.24–26 We will consider the following items of the risk of bias: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other potential items that can be a source of bias. For each item, an assignment of the risk of bias will be provided according the following categories: low risk, unclear risk and high risk. Given that participants and personnel might not always be blinded due to the nature of the non-pharmacological interventions, performance bias will usually not be used for downgrading the level of evidence within the risk of bias assessment when the outcome is objective.

Data synthesis

Where a sufficient number of primary studies are identified, a meta-analysis will be performed. Dichotomous outcomes results will be expressed as risk ratio with 95% CIs. Where continuous scales of measurement are used to assess the effects of treatment, the mean difference will be used; the standardised mean difference will be used if different scales have been used. For time to event data (eg, survival,), hazard ratios (HR) will be used to calculate the magnitude of effect. The HR and variance corresponding to the published survival data will be used. Where this will not be directly available from the published version we will contact authors. Otherwise we will estimate HR and variance using log rank p value, number randomised, events or survival curves when available.27 Where data are available, cumulative event rate will be calculated. Analysis will be performed according to an intention-to-treat principle. For missing data, trial authors will be contacted or sensitivity analyses will be performed.26 Heterogeneity will be evaluated using aχ2 test with N-1 df, with an alpha of 0.10 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test.24 Source of heterogeneity will be evaluated by assessing the participants, the intervention, the comparison group and the outcomes and by visually assessing the forest plots. Review Manager (Revman V.5.3) will be used for data synthesis. Data will be pooled using both the random-effects model and the fixed-effect model to ensure robustness.

Final consideration

DF represents a significant problem in paediatric dentistry, interesting about 2 children in 10. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions represent useful instruments to treat children who suffer from DF. However, there has been no comprehensive systematic reviews concerning both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to manage DFA in children and adolescents undergoing dental procedures. Hence, it is necessary to perform a systematic review to assess efficacy and safety of using pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of dental anxiety in paediatric subjects.

Our review may provide evidence for researchers and be helpful for clinical practitioners in treating children with DFA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Silvano Gallus for his precious hints.

Footnotes

Contributors: SC, LP, RG, EL and AM conceived, drafted and approved the final version of the protocol.

Funding: This study is funded by the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control—Ministry of Health (Grant CCM 2015). The study sponsor is not involved in the study design and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of the article or the decision to submit it for publication. The authors are independent from study sponsors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behaviour management problems in children and adolescents: a review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent 2007;17:391–406. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00872.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Porritt J, Buchanan H, Hall M, et al. Assessing children's dental anxiety: a systematic review of current measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013;41:130–42. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00740.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Winer GA. A review and analysis of children's fearful behavior in dental settings. Child Dev 1982;53:1111–33. 10.2307/1129002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Moammar K, Cash A, Donaldson N, et al. Psychological interventions for reducing dental anxiety in children (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD007691. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wogelius P, Poulsen S, Sørensen HT. Prevalence of dental anxiety and behavior management problems among six to eight years old Danish children. Acta Odontol Scand 2003;61:178–83. 10.1080/00016350310003468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kyritsi MA, Dimou G, Lygidakis NA. Parental attitudes and perceptions affecting children's dental behaviour in Greek population. A clinical study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2009;10:29–32. 10.1007/BF03262664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gustafsson A, Arnrup K, Broberg AG, et al. Child dental fear as measured with the Dental Subscale of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule: the impact of referral status and type of informant (child versus parent). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2010;38:256–66. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salem K, Kousha M, Anissian A, et al. Dental fear and concomitant factors in 3-6 year-old children. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects 2012;6:70–4. 10.5681/joddd.2012.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore R, Brødsgaard I. Dentists' perceived stress and its relation to perceptions about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001;29:73–80. 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.00011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ter Horst G, de Wit CA. Review of behavioural research in dentistry 1987-1992: dental anxiety, dentist-patient relationship, compliance and dental attendance. Int Dent J 1993;43:265–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong HM, Humphris GM, Lee GT. Preliminary validation and reliability of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Psychol Rep 1998;83:1179–86. 10.2466/PR0.83.7.1179-1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aartman IHA, van Everdingen T, Hoogstraten J, et al. Appraisal of behavioral measurement techniques for assessing dental anxiety and fear in children: a review. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 1996;18:153–71. 10.1007/BF02229114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Appukuttan DP. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2016;8:35–50. 10.2147/CCIDE.S63626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lourenço-Matharu L, Ashley PF, Furness S. Sedation of children undergoing dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;3:CD003877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harbuz DK, O'Halloran M. Techniques to administer oral, inhalational, and IV sedation in dentistry. Australas Med J 2016;9:25–32. 10.4066/AMJ.2015.2543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matharu LL, Ashley PF. What is the evidence for paediatric dental sedation? J Dent 2007;35:2–20. 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenbaum PE, Turner C, Cook EW, et al. Dentists' voice control: effects on children's disruptive and affective behavior. Health Psychol 1990;9:546–58. 10.1037/0278-6133.9.5.546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buchanan H, Niven N. Self-report treatment techniques used by dentists to treat dentally anxious children: a preliminary investigation. Int J Paediatr Dent 2003;13:9–12. 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2003.00413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Armfield JM, Heaton LJ. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dent J 2013;58:390–407. 10.1111/adj.12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lynn SJ, Green JP, Kirsch I, et al. Grounding hypnosis in science: the 'New' APA division 30 definition of hypnosis as a step backward. Am J Clin Hypn 2015;57:390–401. 10.1080/00029157.2015.1011472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roberts JF, Curzon ME, Koch G, et al. Review: behaviour management techniques in paediatric dentistry. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2010;11:166–74. 10.1007/BF03262738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abraha I, Cozzolino F, Orso M, et al. A systematic review found that deviations from intention-to-treat are common in randomized trials and systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;84:37–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.