Abstract

Objectives

In stable coronary artery disease (CAD), coronary revascularisation may reduce mortality of patients with a certain amount of left ventricular myocardial ischaemia. However, revascularisation does not always follow the guidance suggested by ischaemia testing. We compared outcomes in patients without ischaemia who had either revascularisation or medical treatment.

Design and population

Based on registries, 1327 consecutive patients with normal myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) and 278 with fixed perfusion defects were followed for a median of 6.1 years. Most patients received medical therapy alone (Med), but 26 (2%) with a normal MPS and 15 (5%) with fixed perfusion defects underwent revascularisation (Revasc).

Outcome measures

Incidence rates of all-cause death (ACD) and rates of cardiac death/myocardial infarction (CD/MI).

Results

With a normal MPS, the ACD rate was 6.2%/year in the Revasc group versus 1.9%/year in the Med group (p=0.01); the CD/MI rates were 6.9%/year and 0.6%/year, respectively (p<0.00001). Results persisted after adjustment for predictors of revascularisation, in particular angina score, and in comparisons of matched Revasc and Med patients. With fixed defects, the ACD rate was 9.1%/year in the Revasc group and 6.7%/year in the Med group (p=0.44); the CD/MI rate was 5.0%/year versus 4.2%/year, respectively (p=0.69). If adjusted for angiographic variables or analysed in matched subsets, differences remained insignificant.

Conclusions

With normal MPS, revascularisation conferred a higher risk, even after adjustment for predictors of revascularisation. With fixed defects, the Revascversus Med difference was close to equipoise. Hence, in patients with stable CAD without ischaemia, we could not find evidence to justify exceptional revascularisation.

Keywords: ischaemic heart disease, myocardial perfusion imaging, functional ischaemia test, survival benefit, all-cause death

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The observational design gave a rare chance to study outcome in a clinical setting, where myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) results were open to referring clinicians.

Endpoints were collected from comprehensive national registries ensuring a high validity.

Rationales for the choice of post-MPS treatment were found in medical records, which may have reduced the ability to address explanatory factors.

The major limitation was the small number of patients undergoing revascularisation (n=41).

However, careful adjustment was undertaken in order to achieve a fair comparison of subgroups, and a matching approach was also used.

We focused on hard events, which are indisputable. On the other side, we cannot tell from the present material whether revascularisation yielded an amelioration of symptoms.

Introduction

In stable angina pectoris patients at low to intermediate risk of coronary artery disease (CAD), it is recommended to use non-invasive testing as a gatekeeper to coronary angiography.1 2 Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) is an ischaemia test that effectively stratifies patients with an intermediate pre-test risk into groups with low or high post-test risk and, hence, identifies potential candidates for coronary revascularisation.3–5 Revascularisation is often performed with the intention to improve symptoms or prognosis; however, a survival benefit over optimal medical therapy has not been documented in patients with stable CAD.6–8 Data from registry-based studies suggest that only in the presence of a certain amount of ischaemia is the prognosis with respect to hard events better with coronary revascularisation than with conservative therapy.9 10 Nevertheless, in daily routine a small proportion of patients with normal MPS or fixed defects still undergoes revascularisation. It remains an open question whether this reflects a clinically justified exception to the regular practice. Addressing this question is a non-trivial task as a potential inferior prognosis in the revascularised patients may simply reflect a proper clinical selection of high-risk patients with a real need for revascularisation, regardless of the MPS result. Comparison of patients with similar risk profiles as regards potential prognostic factors related to the treatment decision might allow for an answer. In an observational design, we compared the outcome with and without coronary revascularisation in consecutive patients with symptoms of stable CAD but without ischaemia in a setting, where the MPS results were open to the treating physicians.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

From a consecutive series of 2157 MPS performed 2002–2007 at Odense University Hospital for suspected or known CAD in patients who did not participate in a research project, 1327 patients had normal scintigraphic findings while 278 demonstrated fixed perfusion defects. Results were analysed for all patients and for subsets undergoing early revascularisation (Revasc) or receiving pure medical therapy (Med). Early revascularisation was defined as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) within 180 days from MPS, while performed >180 days later was termed late revascularisation. Trial design and methods were published previously.11 The study was approved by the local data protection committee.

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy

MPS was performed as single photon emission CT with technetium-99m sestamibi using a standard maximum exercise test or pharmacological stress by adenosine, dipyridamole or dobutamine. In the early study period, non-gated acquisitions were used. Later, gated studies were used with at-rest left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) being available in 648 patients (49%) with normal MPS and 147 patients (53%) with fixed defects. For post-stress LVEF, the numbers were 687 (52%) and 123 (44%), respectively. Scans were interpreted semiquantitatively and deemed normal in case of normal radionuclide distribution throughout the myocardium in the presence also of normalcy with respect to available non-perfusion markers like wall thickening/motion, ventricular size and LVEF. All abnormal scans were reviewed by an experienced reader (AJ) blinded to clinical data. Extent and severity of perfusion defects at stress imaging were converted to percentage myocardium and categorised as small (5%–9% of the myocardium), moderate (10%–14%) or large (>14%).12

Follow-up

History of CAD and medication at the time of MPS were retrieved from medical records and MPS reports. Follow-up ran from the date of the MPS until 31 December 2011. Events during follow-up were appointed by means of regional and national registers as previously described.11 Medical records were examined for treatment decision, and angiographic data were obtained from the Western Denmark Heart Registry comprising records on all coronary angiographies and revascularisation procedures performed in Western Denmark, including angina score according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS).13

Statistics

Continuous and categorical variables are shown by means of descriptive statistics and frequency counts including percentages, respectively. Intergroup differences in continuous variables were tested by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test; frequencies were compared by Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test. Main endpoints were all-cause death (ACD) and cardiac death (defined as death from ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure or malignant arrhythmia) or non-fatal myocardial infarction (CD/MI). Time until event is illustrated with cumulative incidence functions. Cause-specific HRs (CSHRs) based on a Cox proportional hazard model as well as subdistribution HRs (SDHRs) based on the Fine and Gray regression model14 were used to assess the difference between Revasc and Med. The HRs were adjusted for main predictors of revascularisation, which were identified by comparison of the two treatment groups and an analysis of the reasons given in the medical records of revascularised patients. Adjustment was performed for one covariate at a time as well as in multivariate models. When considering ACD, late revascularisation was regarded as a competing event in order not to bias the natural course. When considering CD/MI, non-cardiac death and late revascularisation were regarded as competing events. Following the general advice to consider all competing events in the statistical analysis,15 16 we present cumulative incidence functions for all four events but restrict reporting of HRs to the two main endpoints.

Furthermore, a matching approach was used. For each revascularised patient, we found a medically treated match with identical or nearly identical values for the variables predictive of revascularisation. Event incidences for the revascularised patients and their matches were compared by cumulative incidence curves, CSHRs and SDHRs.

The significance level was set to 5%. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA v.12. Matching was performed with the ‘optmatch’ program17 and incidence rates were compared with the ‘stir’ command.

Results

Early revascularisation was performed in 26 patients (2%) with normal MPS and in 15 patients (5%) with fixed defects. Characteristics are given in table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All | Revascularisation | Medical therapy | p Value | |

| (a) Patients with normal MPS | ||||

| N | 1327 | 26 | 1301 | |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 59.5±11.8 | 62.1±12.2 | 59.5±11.8 | 0.29 |

| Male | 574 (43) | 17 (65) | 557 (43) | 0.03 |

| Known CAD | 248 (19) | 15 (58) | 233 (18) | <0.0001 |

| History | ||||

| MI | 87 (7) | 6 (23) | 81 (6) | 0.005 |

| PCI | 149 (11) | 12 (46) | 137 (11) | <0.0001 |

| CABG | 59 (4) | 2 (8) | 57 (4) | 0.32 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 202 (15) | 5 (19) | 197 (15) | 0.58 |

| Medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 797 (60) | 23 (88) | 774 (59) | 0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 462 (35) | 20 (77) | 442 (34) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 325 (24) | 9 (35) | 316 (24) | 0.25 |

| Nitrates | 279 (21) | 8 (31) | 271 (21) | 0.23 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 481 (36) | 16 (62) | 465 (36) | 0.01 |

| LVEF, rest, N | 648 | 15 | 633 | 1.00 |

| <30% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30≤ LVEF<50% | 34 (5) | 0 | 34 (5) | |

| ≥50% | 614 (95) | 15 (100) | 599 (95) | |

| LVEF, stress, N | 687 | 16 | 671 | 0.63 |

| <30% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30≤ LVEF<50% | 41 (6) | 0 | 41 (6) | |

| ≥50% | 646 (94) | 16 (100) | 630 (94) | |

| Family history of CAD, N | 216 | 23 | 193 | 0.83 |

| Positive | 113 (52) | 13 (57) | 100 (52) | |

| CCS score, N | 223 | 26 | 197 | 0.01 |

| 1 | 122 (55) | 10 (38) | 112 (57) | |

| 2 | 76 (34) | 8 (31) | 68 (35) | |

| 3 | 24 (11) | 8 (31) | 16 (8) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| Smoking, N | 203 | 22 | 181 | 0.41 |

| Current | 56 (28) | 8 (36) | 48 (27) | |

| Never | 79 (39) | 6 (27) | 73 (40) | |

| Ceased | 68 (34) | 8 (36) | 60 (33) | |

| Stenotic vessels, N | 210 | 26 | 184 | <0.0001 |

| 0 | 101 (48) | 2 (8) | 99 (54) | |

| 1 | 59 (28) | 10 (38) | 49 (27) | |

| 2 | 30 (14) | 7 (27) | 23 (13) | |

| 3 | 20 (10) | 7 (27) | 13 (7) | |

| (b) Patients with fixed perfusion defects | ||||

| N | 278 | 15 | 263 | |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 62.5±10.2 | 61.6±11.5 | 62.6±10.1 | 0.63 |

| Male | 214 (77) | 14 (93) | 200 (76) | 0.20 |

| Known CAD | 196 (71) | 11 (73) | 185 (70) | 1.00 |

| History | ||||

| MI | 152 (55) | 8 (53) | 144 (55) | 1.00 |

| PCI | 101 (36) | 6 (40) | 95 (36) | 0.79 |

| CABG | 76 (27) | 3 (20) | 73 (28) | 0.77 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 59 (21) | 5 (33) | 54 (21) | 0.33 |

| Medication | ||||

| Aspirin | 233 (84) | 12 (80) | 221 (84) | 0.72 |

| Beta blocker | 177 (64) | 9 (60) | 168 (64) | 0.79 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 76 (27) | 6 (40) | 70 (27) | 0.25 |

| Nitrates | 75 (27) | 4 (27) | 71 (27) | 1.00 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 169 (61) | 8 (53) | 161 (61) | 0.59 |

| Size of defects | 0.62 | |||

| Small (5%–9%) | 92 (33) | 4 (27) | 88 (33) | |

| Medium (10%–14%) | 60 (22) | 2 (13) | 58 (22) | |

| Large (>14%) | 126 (45) | 9 (60) | 117 (45) | |

| LVEF, rest, N | 147 | 4 | 143 | 0.79 |

| <30% | 20 (14) | 0 | 20 (14) | |

| 30≤LVEF<50% | 57 (39) | 1 (25) | 56 (39) | |

| ≥50% | 70 (48) | 3 (75) | 67 (47) | |

| LVEF, stress, N | 123 | 5 | 118 | 0.84 |

| <30% | 21 (17) | 0 | 21 (18) | |

| 30≤LVEF<50% | 48 (39) | 2 (40) | 46 (39) | |

| ≥50% | 54 (44) | 3 (60) | 51 (43) | |

| Family history of CAD, N | 106 | 14 | 92 | 0.77 |

| Positive | 45 (42) | 5 (36) | 40 (43) | |

| CCS score, N | 115 | 15 | 100 | 0.13 |

| 1 | 73 (63) | 7 (47) | 66 (66) | |

| 2 | 25 (22) | 3 (20) | 22 (22) | |

| 3 | 16 (14) | 5 (33) | 11 (11) | |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Smoking, N | 102 | 13 | 89 | 1.00 |

| Current | 36 (35) | 5 (38) | 31 (35) | |

| Never | 19 (19) | 2 (15) | 17 (19) | |

| Ceased | 47 (46) | 6 (46) | 41 (46) | |

| Stenotic vessels, N | 108 | 15 | 93 | 0.002 |

| 0 | 15 (14) | 0 | 15 (16) | |

| 1 | 26 (24) | 3 (20) | 23 (25) | |

| 2 | 34 (31) | 11 (73) | 23 (25) | |

| 3 | 33 (31) | 1 (7) | 32 (34) | |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MPS, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The decision to revascularise was clearly associated with symptoms and angiographic findings but less with MPS results (table 2). In four cases of normal MPS, revascularisation was performed following a new incident independent of the symptoms prompting MPS.

Table 2.

Reasons for revascularisation according to medical records

| DM | History | Angio findings* | CCS score | Time from MPS to revascularisation (days) | Type of revascularisation | Reasoning to decide for revascularisation was based on |

| (a) Patients with normal MPS | ||||||

| 0-VD | 3 | 83 | PCI | Angio, sympt, EET | ||

| PCI | 2-VD | 2 | 72 | PCI | Angio, sympt, ECG changes during dobutamine stress | |

| + | 2-VD | 2 | 159 | CABG | Angio, sympt, IVUS | |

| MI, PCI | 2-VD | 2 | 127 | PCI | Angio, EET, history of MI | |

| + | 1-VD | 1 | 157 | PCI | MI, that is, recurrent event | |

| 3-VD | 3 | 5 | PCI | Angio | ||

| + | 1-VD | 3 | 71 | PCI | Angio, sympt | |

| PCI, CABG | 3-VD | 1 | 169 | PCI | Angio, sympt | |

| 0-VD | 1 | 49 | PCI | Angio, IVUS, EET | ||

| 1-VD | 1 | 93 | PCI | MI, that is, recurrent event | ||

| 1-VD | 2 | 149 | PCI | Angio, IVUS, sympt | ||

| PCI | 2-VD | 1 | 131 | PCI | MI, that is, recurrent event | |

| PCI | 1-VD | 1 | 116 | PCI | Angio, sympt | |

| + | MI, PCI | 3-VD | 3 | 43 | PCI | Angio, sympt |

| 1-VD | 3 | 170 | CABG | Angio, IVUS, persistent sympt | ||

| 1-VD | 2 | 43 | PCI | Angio, persistent sympt | ||

| 1-VD | 1 | 145 | PCI | Angio, sympt | ||

| MI, PCI | 3-VD | 3 | 95 | PCI | Angio, sympt | |

| + | MI, PCI | 2-VD | 2 | 104 | PCI | Angio, sympt |

| MI, PCI | 3-VD | 3 | 104 | CABG | Angio, sympt | |

| PCI | 1-VD | 3 | 37 | PCI | Angio, sympt | |

| MI, PCI, CABG | 3-VD | 1 | 16 | PCI | MI, that is, recurrent event | |

| PCI | 3-VD | 1 | 43 | PCI | Angio, sympt | |

| 1-VD | 2 | 76 | PCI | Angio, sympt | ||

| 2-VD | 1 | 49 | PCI | Angio, sympt | ||

| 2-VD | 2 | 53 | PCI | Angio, ECG changes during adenosine stress | ||

| DM | History | Size of defect | Angio findings* | CCS score | Time from MPS to revascularisation (days) | Type of revascularisation | Reasoning to decide for revascularisation was based on |

| (b) Patients with fixed defects | |||||||

| MI, CABG, PCI | Large | 3-VD | 3 | 36 | PCI | Sympt, angio | |

| + | MI, CABG | Large | 2-VD | 3 | 49 | PCI | Angio |

| Mod. | 1-VD | 3 | 105 | PCI | Sympt, angio | ||

| PCI | Large | 2-VD | 3 | 158 | PCI | Sympt, angio | |

| MI, PCI | Small | 3-VD | 2 | 98 | CABG | Sympt, angio | |

| PCI | Small | 2-VD | 3 | 64 | PCI | Sympt, angio | |

| Small | 2-VD | 1 | 60 | PCI | Angio | ||

| MI, PCI | Large | 2-VD | 1 | 70 | CABG | Sympt, angio | |

| MI, PCI | Large | 2-VD | 1 | 72 | PCI | Angio | |

| MI | Large | 2-VD | 1 | 25 | CABG | Angio | |

| + | PCI | Large | 2-VD | 1 | 148 | PCI | Reduced LVEF, viability, angio |

| + | MI, CABG | Large | 2-VD | 2 | 71 | PCI | Sympt, angio |

| + | MI | Large | 2-VD | 1 | 16 | CABG | Angio |

| + | Mod. | 1-VD | 1 | 85 | PCI | Sympt, angio | |

| Small | 1-VD | 2 | 77 | PCI | Angio | ||

*None had stenosis of the left main stem. Degree and appearance of stenoses were not reported.

Angio, angiography; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; DM, diabetes mellitus; EET, exercise ECG testing; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; mod., moderate; MPS, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; sympt , symptoms; VD , vessel disease.

Median follow-up (range) was 6.1 years (0.02–9.96). Table 3 shows the cumulative numbers of events during follow-up. With normal MPS, the number of MIs was higher than the number of CDs (3% vs 1%, p<0.0001), whereas in the patients with fixed defects, the disparity, although insignificant, was the reverse (10% vs 14%, p=0.19). In none of the MPS groups did the CD/ACD ratio differ between subgroups; being 2/7 and 14/150, respectively (p=0.15) in normal MPS and 3/7 versus 35/88 (p=1.00) in patients with fixed defects (table 3).

Table 3.

Cumulative number of events during follow-up

| Events | Normal MPS | Fixed defects | ||||||

| All N (% of 1327) |

Revascularisation N (% of 26) |

Medical therapy N (% of 1301) |

p Value | All N (% of 278) |

Revascularisation N (% of 15) |

Medical therapy N (% of 263) |

p Value | |

| No event | 1079 (81) | 14 (54) | 1065 (82) | 0.001 | 140 (50) | 7 (47) | 133 (51) | 0.80 |

| Any event (death/MI/revascularisation) | 248 (19) | 12 (46) | 236 (18) | 138 (50) | 8 (53) | 130 (49) | ||

| Death | 157 (12) | 7 (27) | 150 (12) | 0.03 | 95 (34) | 7 (47) | 88 (33) | 0.40 |

| Cardiac death | 16 (1) | 2 (8) | 14 (1) | 0.04 | 38 (14) | 3 (20) | 35 (13) | 0.44 |

| MI | 43 (3) | 5 (19) | 38 (3) | 0.001 | 27 (10) | 1 (7) | 26 (10) | 1.00 |

| MI or death | 191 (14) | 10 (38) | 181 (14) | 0.002 | 111 (40) | 8 (53) | 103 (39) | 0.29 |

| MI or cardiac death | 57 (4) | 7 (27) | 50 (4) | <0.0001 | 58 (21) | 4 (27) | 54 (21) | 0.53 |

| PCI | 81 (6) | 1 (4) | 80 (6) | 1.00 | 48 (17) | 1 (7) | 47 (18) | 0.48 |

| CABG | 15 (1) | 2 (8) | 13 (1) | 0.03 | 6 (2) | 0 | 6 (2) | 1.00 |

| PCI/CABG | 92 (7) | 3 (12) | 89 (7) | 0.42 | 50 (18) | 1 (7) | 49 (19) | 0.49 |

| MI/cardiac death/revascularisation | 124 (9) | 9 (35) | 115 (9) | <0.0001 | 87 (31) | 4 (27) | 83 (32) | 0.78 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MI, myocardial infarction; MPS, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

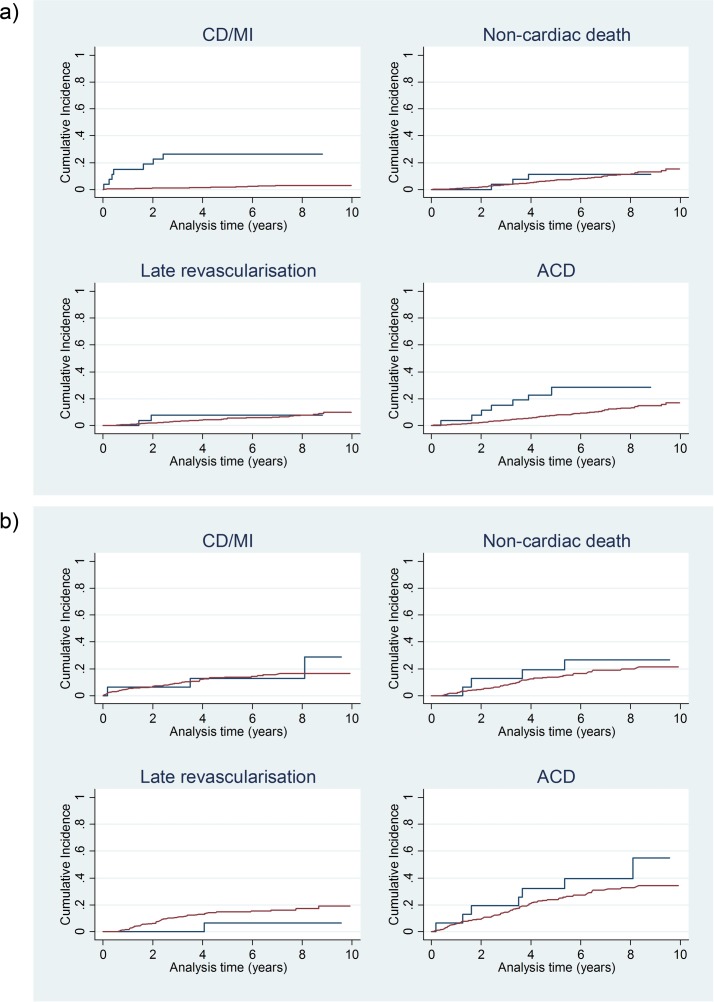

Cumulative incidence functions shown in figure 1 indicated no difference in the incidence of non-cardiac deaths between the two treatment groups for neither patients with normal MPS, nor patients with fixed defects. As regards late revascularisation, the Med curve tended to run above the Revasc curve in case of fixed defects; however, the difference was not significant. With normal MPS, substantially different incidence rates of the main endpoints could be observed. The ACD rate was 6.2%/year in the Revasc group compared with 1.9%/year in the Med group (p=0.01) and the CD/MI rate was 6.9%/year versus 0.6%/year, respectively (p<0.00001). In case of fixed defects, there were no significant intergroup differences, and Revasc/Med ratios were similar for both endpoints: the ACD rate was 9.1%/year in the Revasc group and 6.7%/year in the Med group (p=0.44) and the CD/MI rate was 5.0%/year versus 4.2%/year, respectively (p=0.69).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence functions. Blue lines: revascularisation; red lines: medical therapy. (a) Patients with normal myocardial perfusion scintigraphy; (b) patients with fixed perfusion defects. ACD, all-cause death; CD, cardiac death; MI, myocardial infarction.

Quantification of effects and adjustment

Judged from tables 1 and 2, variables CAD, previous MI, previous PCI, CCS score and number of stenotic coronary arteries were associated with the decision to revascularise despite normal MPS. The use of aspirin, beta blockers and lipid-lowering agents was unequally distributed and, hence, could be a surrogate for a disease state also predictive of revascularisation. Gender was also unevenly distributed and, therefore, considered in the models. In patients with fixed effects, the only significant association found was for the number of stenotic arteries. The lack of significance for the other variables may, however, mainly reflect lack of power due to the small number of revascularised patients. It seems reasonable to assume that variables predictive of the treatment decision in patients with normal MPS would also be potential predictors in patients with fixed effects. Hence, we used the same list of (potential) predictors.

Unadjusted and adjusted CSHRs and SDHRs comparing the Revasc and Med groups are shown in table 4. Adjustment for clinical and/or angiographic variables did not change the HRs with normal MPS, which were always in the magnitude of 3–5 for ACD and >9 for CD/MI, all being significantly different from 1. With fixed defects, the HR was never significantly different from 1. Adjusted for clinical variables, the HRs for both outcomes stayed in the magnitude of 1.2–1.8. However, with adjustment for angiographic variables the HR changed more substantially to values around 2 for ACD and between 0.7 and 0.9 for CD/MI.

Table 4.

Cause-specific HRs and subdistribution HRs of the revascularisation versus medical therapy difference

| ACD | CD/MI | |||||||

| CSHR | p Value | SDHR | p Value | CSHR | p Value | SDHR | p Value | |

| (a) Patients with normal MPS | ||||||||

| Univariate analysis | 3.85 | 0.001 | 3.42 | 0.002 | 15.44 | <0.0001 | 14.09 | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted for clinical variables | ||||||||

| Age | 3.22 | 0.003 | 3.12 | 0.005 | 12.93 | <0.0001 | 11.75 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | 3.58 | 0.001 | 3.17 | 0.003 | 15.11 | <0.0001 | 13.85 | <0.0001 |

| Age, gender | 2.89 | 0.007 | 2.80 | 0.01 | 12.37 | <0.0001 | 11.26 | <0.0001 |

| DM | 3.81 | 0.001 | 3.39 | 0.002 | 15.30 | <0.0001 | 13.99 | <0.0001 |

| Known CAD | 3.76 | 0.001 | 3.47 | 0.002 | 13.04 | <0.0001 | 12.29 | <0.0001 |

| Previous MI | 3.97 | <0.0001 | 3.52 | 0.002 | 12.76 | <0.0001 | 12.01 | <0.0001 |

| Previous PCI | 4.27 | <0.0001 | 3.87 | 0.001 | 14.42 | <0.0001 | 13.45 | <0.0001 |

| CAD category* | 3.71 | 0.001 | 3.45 | 0.003 | 13.02 | <0.0001 | 12.26 | <0.0001 |

| CAD category*, previous MI | 3.68 | 0.001 | 3.42 | 0.004 | 12.87 | <0.0001 | 12.48 | <0.0001 |

| CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering | 4.22 | <0.0001 | 3.81 | 0.001 | 11.86 | <0.0001 | 11.43 | <0.0001 |

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering | 4.08 | 0.001 | 3.66 | 0.002 | 11.76 | <0.0001 | 11.34 | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted for angiographic variables | ||||||||

| CCS score (n=223/115) | 4.27 | 0.003 | 3.77 | 0.006 | 12.06 | <0.0001 | 11.03 | <0.0001 |

| Number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 4.62 | 0.005 | 4.52 | 0.006 | 9.19 | 0.001 | 9.28 | 0.001 |

| CCS score, number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 4.52 | 0.007 | 4.18 | 0.007 | 9.89 | 0.001 | 9.49 | 0.002 |

| Adjusted for scintigraphic variables | ||||||||

| At-rest LVEF (n=648/147) | 2.87 | 0.08 | 2.97 | 0.08 | 12.78 | <0.0001 | 12.86 | <0.0001 |

| Post-stress LVEF (n=687/123) | 2.70 | 0.09 | 2.80 | 0.10 | 12.74 | <0.0001 | 12.93 | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted for selected variables of all types | ||||||||

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering, CCS score (n=223/115) | 4.55 | 0.004 | 3.48 | 0.009 | 29.29 | <0.0001 | 26.69 | <0.0001 |

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering, number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 4.30 | 0.02 | 3.79 | 0.03 | 11.70 | 0.001 | 11.80 | 0.001 |

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering, CCS score, number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 4.14 | 0.02 | 3.31 | 0.06 | 20.86 | 0.001 | 20.23 | 0.001 |

| (b) Patients with fixed perfusion defects | ||||||||

| Univariate analysis | 1.49 | 0.31 | 1.68 | 0.18 | 1.24 | 0.72 | 1.29 | 0.66 |

| Adjusted for clinical variables | ||||||||

| Age | 1.50 | 0.30 | 1.75 | 0.16 | 1.26 | 0.70 | 1.28 | 0.67 |

| Gender | 1.41 | 0.39 | 1.60 | 0.22 | 1.22 | 0.74 | 1.30 | 0.66 |

| Age, gender | 1.44 | 0.36 | 1.69 | 0.19 | 1.26 | 0.71 | 1.30 | 0.66 |

| DM | 1.42 | 0.39 | 1.63 | 0.23 | 1.19 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 0.40 |

| Known CAD | 1.49 | 0.31 | 1.68 | 0.17 | 1.20 | 0.76 | 1.28 | 0.67 |

| Previous MI | 1.50 | 0.31 | 1.69 | 0.17 | 1.24 | 0.72 | 1.29 | 0.66 |

| Previous PCI | 1.52 | 0.29 | 1.70 | 0.16 | 1.26 | 0.70 | 1.29 | 0.65 |

| CAD category* | 1.55 | 0.27 | 1.76 | 0.15 | 1.28 | 0.68 | 1.31 | 0.64 |

| CAD category*, previous MI | 1.56 | 0.26 | 1.77 | 0.14 | 1.29 | 0.67 | 1.32 | 0.64 |

| CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering | 1.39 | 0.41 | 1.58 | 0.25 | 1.28 | 0.69 | 1.31 | 0.66 |

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering | 1.34 | 0.47 | 1.51 | 0.30 | 1.27 | 0.69 | 1.32 | 0.65 |

| Adjusted for angiographic variables | ||||||||

| CCS score (n=223/115) | 1.61 | 0.27 | 1.93 | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.80 |

| Number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 2.35 | 0.09 | 2.67 | 0.06 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.69 |

| CCS score, number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 1.76 | 0.28 | 2.27 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 0.58 |

| Adjusted for scintigraphic variables | ||||||||

| At-rest LVEF (n=648/147) | 0.85 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.00 | –† | –† | –† | –† |

| Post-stress LVEF (n=687/123) | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.73 | –† | –† | –† | –† |

| Size of defects | 1.23 | 0.61 | 1.38 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.90 |

| Adjusted for selected variables of all types | ||||||||

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering, CCS score (n=223/115) | 1.54 | 0.38 | 1.99 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering, number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 3.68 | 0.06 | 4.31 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| Gender, CAD category*, previous MI, aspirin, beta blocker, lipid lowering, CCS score, number of stenotic vessels (n=210/108) | 3.05 | 0.11 | 4.37 | 0.07 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.94 |

*In order to reduce the number of covariates, and because of correlation between CAD and previous revascularisation, a CAD category variable was generated, taking into account the history of both CAD and previous revascularisation: 1 = suspected CAD; 2 = known CAD with no previous revascularisation; 3 = known CAD with previous revascularisation.

†Fitting of Cox model indicated complete separation; hence, no results could be presented.

ACD, all-cause death; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CD, cardiac death; CSHR, cause-specific HR; DM, diabetes mellitus; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MPS, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SDHR, subdistribution HR.

Scintigraphic variables, available only in a subgroup of all patients, were also to some degree associated with treatment decisions. All the Revasc patients with normal MPS had LVEF≥50%, whereas some of the Med patients had 30≤LVEF<50% (table 1a). Adjustment for LVEF category slightly reduced the HRs for ACD but not for CD/MI (table 4a). One out of four of the Revasc patients with fixed defects had a moderately reduced at-rest LVEF (30≤LVEF<50%), but no one had a severely reduced LVEF (<30%), which was the case in 14% of the Med patients (table 1b). Adjustment for LVEF category reduced the HRs for ACD, whereas for CD/MI, numbers were too small for an estimation. Similarly, in spite of no significant intergroup difference in size of perfusion defects, adjustment for defect size slightly reduced the HR for both endpoints (table 4b).

Results from the matching procedure can be seen from the online supplementary material. For matched subsets, results were similar to those from the entire groups; in case of normal MPS, the CSHR was 7.97 (p=0.05) for ACD, 4.12 (p=0.08) for CD/MI. With fixed defects, the CSHR was 1.00 (p=1.00) for ACD and 0.70 (p=0.67) for CD/MI, respectively. Cumulative incidence functions resembled those for the entire groups. Detailed results are given in the online supplementary table and online supplementary figure.

bmjopen-2017-016169supp001.pdf (7.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016169supp002.pdf (6.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016169supp003.pdf (30.3KB, pdf)

Discussion

In this study, 2% of patients with normal MPS and 5% with fixed perfusion defects underwent early coronary revascularisation; that is, exceptional revascularisation. With normal MPS, Revasc patients had significantly higher event rates than Med patients. With fixed defects, no significant intergroup differences were observed. Results persisted after adjustment for predictors of revascularisation as well as after matching. Noteworthy, MPS was conducted as a part of the routine diagnostic work-up and results were open to the referring clinicians. Still, revascularisation was undertaken in some patients, probably primarily based on angiographic and clinical findings.

Use of MPS

In patients with stable angina, an ischaemia test is far from always performed before angiography.18 19 An anatomical approach to the CAD diagnosis and quantification typically leads to more revascularisation procedures than a functional approach.20–22 However, strategies involving MPS have a greater prognostic power than those without functional testing.23 24

Optimal risk stratification derives from the ability of a normal MPS to identify patients at exceedingly low risk, and that of an abnormal scan to identify patients at greater risk, thus rendering a number of catheterisation and invasive interventions superfluous.25–27 Following a normal MPS, the annual death rate is generally <2% and the annual rate of hard cardiac events<1%, a little higher in risk groups.28 29 We and others previously found a general warranty period following a normal MPS of 5 years11.30 Thus, under usual conditions, cardiac catheterisation is not warranted in the presence of a normal study, unless there is a change in symptoms.

A small percentage of patients with normal scans do have events within the warranty period. In our population of 1327 patients with normal MPS, 4 patients (0.3%) underwent revascularisation within 6 months from MPS because of an acute MI. One had diabetes, one had chronic kidney disease and two had known CAD. This supports previous findings of a poorer prognosis for high-risk subgroups and underscores the additional prognostic value of clinical findings to MPS results. It also illustrates the fact that MI—more than death—is hard to anticipate.31 MIs can break out in vessels with a normal appearance,32 33 whereas stenotic and occluded arteries often come with collaterals, preventing MI or at least limiting its size.34 Hence, although the occurrence of MI is associated with the presence of atherosclerosis, it may not be correlated to its severity, and therefore, MPS—like other imaging techniques—cannot predict specific lesions but patients at risk.35 36

The risk of false negative MPS results caused by balanced ischaemia was reduced as non-perfusion scan markers were also taken into consideration. LV function in the shape of LVEF has an independent prognostic and predictive value.3 10 However, decision to perform revascularisation in our patients was in general not based on the presence of a reduced LVEF as all Revasc patients with normal MPS had preserved LVEFs, and far from all patients with an LVEF <50% underwent revascularisation.

Dominant MPS parameters driving subsequent resource utilisation are extent and severity of reversible perfusion defects.12 In addition, a variety of clinical elements, most importantly anginal symptoms, further influence referral rates.20 Thus, when patients with normal scans or scans showing only mild ischaemia are referred to angiography, this is typically based on clinical symptoms.37 In former reports from the USA, 3% of patients without ischaemia were referred to angiography, and revascularisation was performed in one-fifth of these.38–40 The numbers in our series were higher.

Strengths and limitations

Contrary to previous reports on post-MPS assignment in which the authors were left to speculate on possible reasons for paradoxical treatments,20 we went through medical records describing rationales for the choice of treatment, well aware that it is difficult to find specific information on the reason for a clinical decision in retrospect. Careful adjustment was undertaken in order to achieve a fair comparison of subgroups. Due to a low number of revascularisations, PCI and CABG were looked at together. This may, however, be inappropriate as several studies have shown that CABG-treated patients have a lower MI rate compared with PCI-treated patients.

Subsets treated exceptionally, given the MPS findings, constituted a minority of our patients. Considering the small number of Revasc patients compared with Med patients, it was not equitable to estimate a propensity score. However, results from Cox models adjusted for individual covariates are comparable to results from propensity score-adjusted Cox models.41 Adjustment for different predictors of revascularisation did not change our results; specifically, differences persisted after adjustment for angina score, one of the most important predictors of revascularisation. In addition, results of the matching approach were comparable to those from Cox modelling, that is, effects observed in univariate analyses did not vanish. An indicator of an even distribution of non-cardiac health problems affecting prognosis as well as treatment decision was the fact that in none of the subgroups of our patients did we observe a significant difference between the CD/ACD ratios.

In analysing outcome, we focused on hard events. Just like observational studies have indicated that at least 10% of the LV myocardium should be ischaemic in order for the patient to gain a survival benefit,42–44 the same amount seems to be a prerequisite of an improvement in symptoms and exercise capacity.45 46 Hence, revascularisation is unlikely to benefit stable patients with CAD unless there is objective evidence of ischaemia.

Conclusions

In our consecutive series of patients undergoing MPS for stable angina pectoris in the clinical routine, 2% of those with normal MPS and 5% of those with fixed perfusion defects underwent revascularisation against the guidelines. With normal MPS, Revasc was associated with significantly more cardiac events and shorter survival than Med, even after adjustment for clinical, angiographic and scintigraphic variables. With fixed defects, there were no significant differences. Thus, our findings could not justify deviations from the rule to avoid coronary revascularisation in the absence of myocardial ischaemia in patients with stable angina pectoris .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Statistician Sonja Wehberg for assistance with computations.

Footnotes

Contributors: PFH-C, JAS, AJ, OG, AT, SøH, HM and WV contributed to the conception and design. JAS, WV, OG, PFH-C, LOJ and JH were involved in data analysis. All authors were actively involved in collecting and interpreting data, in drafting or revising of the manuscript, and all read and approved the final manuscript submitted. WV was the driving force in applying the statistical analyses as PFH-C was in most aspects of nuclear cardiologic imaging. WV and PFH-C share the last authorship.

Funding: This work was part of a PhD project. The first author received a PhD scholarship from The PhD Research Fund at Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Local data protection committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no unpublished data from this study.

References

- 1. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2012;2012:e354–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bourque JM, Beller GA. Stress myocardial perfusion imaging for assessing prognosis: an update. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:1305–19. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cremer P, Hachamovitch R, Tamarappoo B. Clinical decision making with myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Semin Nucl Med 2014;44:320–9. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hachamovitch R. Does ischemia burden in stable coronary artery disease effectively identify revascularization candidates? Ischemia burden in stable coronary artery disease effectively identifies revascularization candidates. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:e000352 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pursnani S, Korley F, Gopaul R, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:476–90. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.970954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Phillips LM, Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, et al. Lessons learned from MPI and physiologic testing in randomized trials of stable ischemic heart disease: courage, BARI 2D, FAME, and ISCHEMIA. J Nucl Cardiol 2013;20:969–75. 10.1007/s12350-013-9773-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Songco AV, Brener SJ. Initial strategy of revascularization versus optimal medical therapy for improving outcomes in ischemic heart disease: a review of the literature. Curr Cardiol Rep 2012;14:397–407. 10.1007/s11886-012-0278-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iwasaki K. Myocardial ischemia is a key factor in the management of stable coronary artery disease. World J Cardiol 2014;6:130–9. 10.4330/wjc.v6.i4.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simonsen JA, Johansen A, Gerke O, et al. Outcome with invasive versus medical treatment of stable coronary artery disease: influence of perfusion defect size, Ischaemia, and ejection fraction. EuroIntervention 2016;11:1118–24. 10.4244/EIJV11I10A226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simonsen JA, Gerke O, Rask CK, et al. Prognosis in patients with suspected or known ischemic heart disease and normal myocardial perfusion: long-term outcome and temporal risk variations. J Nucl Cardiol 2013;20:347–57. 10.1007/s12350-013-9696-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, et al. Is there a referral Bias against catheterization of patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction? influence of ejection fraction and inducible ischemia on post-single-photon emission computed tomography management of patients without a history of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jensen LO, Maeng M, Kaltoft A, et al. Stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death after drug-eluting and bare-metal stent coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:463–70. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koller MT, Raatz H, Steyerberg EW, et al. Competing risks and the clinical community: irrelevance or ignorance? Stat Med 2012;31:1089–97. 10.1002/sim.4384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, et al. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:648–53. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lunt M. Stata programs developed by Mark Lunt. http://personalpages.manchester.ac.uk/staff/Mark.Lunt/stata.html.

- 18. Gershlick AH, de Belder M, Chambers J, et al. Role of non-invasive imaging in the management of coronary artery disease: an assessment of likely change over the next 10 years. a report from the British Cardiovascular Society Working Group. Heart 2007;93:423–31. 10.1136/hrt.2006.108779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, et al. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA 2008;300:1765–73. 10.1001/jama.300.15.1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hachamovitch R, Nutter B, Hlatky MA, et al. Patient management after noninvasive cardiac imaging results from SPARC (study of myocardial perfusion and coronary anatomy imaging roles in coronary artery disease). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:462–74. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xiu J, Chen G, Zheng H, et al. Comparing treatment outcomes of fractional flow reserve-guided and angiography-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multi-vessel coronary artery diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Invest Med 2016;39:25–36. 10.25011/cim.v39i1.26327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shreibati JB, Baker LC, Hlatky MA. Association of coronary CT angiography or stress testing with subsequent utilization and spending among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2011;306:2128–36. 10.1001/jama.2011.1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gimelli A, Rossi G, Landi P, et al. Stress/Rest myocardial perfusion abnormalities by gated SPECT: still the best predictor of cardiac events in stable ischemic Heart Disease. J Nucl Med 2009;50:546–53. 10.2967/jnumed.108.055954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mowatt G, Brazzelli M, Gemmell H, et al. Systematic review of the prognostic effectiveness of SPECT myocardial perfusion scintigraphy in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease and following myocardial infarction. Nucl Med Commun 2005;26:217–29. 10.1097/00006231-200503000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Høilund-Carlsen PF, Johansen A, Christensen HW, et al. Potential impact of myocardial perfusion scintigraphy as gatekeeper for invasive examination and treatment in patients with stable angina pectoris: observational study without post-test referral bias. Eur Heart J 2006;27:29–34. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Metz LD, Beattie M, Hom R, et al. The prognostic value of normal exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:227–37. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bom MJ, Manders JM, Uijlings R, et al. Negative predictive value of SPECT for the occurrence of MACE in a medium-sized clinic in the Netherlands. Neth Heart J 2014;22:151–7. 10.1007/s12471-014-0524-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Supariwala A, Uretsky S, Singh P, et al. Synergistic effect of coronary artery disease risk factors on long-term survival in patients with normal exercise SPECT studies. J Nucl Cardiol 2011;18:207–14. 10.1007/s12350-010-9330-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schinkel AF, Boiten HJ, van der Sijde JN, et al. 15-Year outcome after normal exercise (99m)Tc-sestamibi myocardial perfusion imaging: what is the duration of low risk after a normal scan? J Nucl Cardiol 2012;19:901–6. 10.1007/s12350-012-9587-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elhendy A, Schinkel A, Bax JJ, et al. Long-term prognosis after a normal exercise stress Tc-99m sestamibi SPECT study. J Nucl Cardiol 2003;10:261–6. 10.1016/S1071-3581(02)43219-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pavin D, Delonca J, Siegenthaler M, et al. Long-term (10 years) prognostic value of a normal thallium-201 myocardial exercise scintigraphy in patients with coronary artery disease documented by angiography. Eur Heart J 1997;18:69–77. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corti R, Fuster V, Badimon JJ. Pathogenetic concepts of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:S7–S14. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02833-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Little WC, Constantinescu M, Applegate RJ, et al. Can coronary angiography predict the site of a subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery disease? Circulation 1988;78:1157–66. 10.1161/01.CIR.78.5.1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naqvi TZ, Hachamovitch R, Berman D, et al. Does the presence and site of myocardial ischemia on perfusion scintigraphy predict the occurrence and site of future myocardial infarction in patients with stable coronary artery disease? Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1521–4. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00184-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pozo E, Agudo-Quilez P, Rojas-González A, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of vulnerable coronary plaque. World J Cardiol 2016;8:520–33. 10.4330/wjc.v8.i9.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arbab-Zadeh A, Fuster V. The myth of the 'vulnerable plaque': transitioning from a focus on individual lesions to atherosclerotic disease burden for coronary artery disease risk assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:846–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.11.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Berman DS, Hachamovitch R, Kiat H, et al. Incremental value of prognostic testing in patients with known or suspected ischemic heart disease: a basis for optimal utilization of exercise technetium-99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:639–47. 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00218-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berman DS, Kang X, Hayes SW, et al. Adenosine myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography in women compared with men. impact of diabetes mellitus on incremental prognostic value and effect on patient management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bateman TM, O'Keefe JH, Williams ME. Incremental value of myocardial perfusion scintigraphy in prognosis and outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Cardiol 1996;11:613–20. 10.1097/00001573-199611000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, et al. Incremental prognostic value of adenosine stress myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography and impact on subsequent management in patients with or suspected of having myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:426–33. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stürmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, et al. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:437.e1–24. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Keefe JH, Bateman TM, Ligon RW, et al. Outcome of medical versus invasive treatment strategies for non-high-risk ischemic heart disease. J Nucl Cardiol 1998;5:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moroi M, Yamashina A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Coronary revascularization does not decrease cardiac events in patients with stable ischemic heart disease but might do in those who showed moderate to severe ischemia. Int J Cardiol 2012;158:246–52. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Shaw LJ, et al. Impact of ischaemia and scar on the therapeutic benefit derived from myocardial revascularization vs. medical therapy among patients undergoing stress-rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1012–24. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Al-Housni MB, Hutchings F, Dalby M, et al. Does myocardial perfusion scintigraphy predict improvement in symptoms and exercise capacity following successful elective percutaneous coronary intervention? J Nucl Cardiol 2009;16:869–77. 10.1007/s12350-009-9112-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johansen A, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Christensen HW, et al. Use of myocardial perfusion imaging to predict the effectiveness of coronary revascularisation in patients with stable angina pectoris. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32:1363–70. 10.1007/s00259-005-1799-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016169supp001.pdf (7.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016169supp002.pdf (6.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016169supp003.pdf (30.3KB, pdf)